The Tainted Legacy of ‘Biblioclasts’

The Case of Otto F. Ege as Collector and Despoiler

As Part II in a series on ‘Manuscript Fragments’, now part of a larger series on Manuscript Studies, Mildred Budny reflects on the predicaments and potentials of dispersed, deliberately detached randomly dispersed leaves from medieval manuscripts collected and dismembered by Otto F. Ege in the first half of the 20th century.

Part I in this series considered the ‘Foundling Hospital’ for Manuscript Fragments, as exhibited in earlier ages of manuscript despoiliation. The issue calls for further exploration, bringing it up to date in an unhappy continuing state of dispersal.

[Part III (next) will reveal ‘A New Leaf from Ege Manuscript 41’]

The Foundling Hospital: The main buildings seen from within the grounds. Coloured engraving by J. Henshall after T. H. Shepherd. Via http://welcomeimages.org/ under Creative Commons

Outcasts Flung into a Wider World

With Uncertain Hopes for Finding Foster Homes

This series of posts continues to celebrate the legacy of the Foundling Hospital in London. We take inspiration from its complicated legacy of a brave endeavour to provide sustenance to lost and abandoned creatures. And so, we consider the implications for reconstitution regarding medieval manuscripts which have been dispersed and, in some ways, abandoned for future rescue, if possible.

In recent years, keeping up with developments in various areas of manuscript studies, I have paid attention to the research discoveries of various scholars, including some Associates of the Research Group on Manuscript Evidence, in their efforts to examine, collate, and reconstruct the traces of medieval and other manuscript fragments let loose onto the world by such agents as the book-destroyer Otto F. Ege (1888‒1951), teacher, lecturer, graphic artist, bookseller, and professed ‘biblioclast’ active mainly at Cleveland, Ohio.

Invaluable contributions to this painstaking research and reconstruction (for the most part virtually) of his dismembered books appear in print, exhibition, or online. They encourage me to report my own contributions, guided by their progress.

Little did I know that paying attention to those generous postings would prove to be valuable, not only in order to learn about progress in manuscript studies as such, but also to provide breakthroughs in some of the research I was already developing. It can help to pay attention, huh?

More ‘Foundlings’ Identified

In preparing the Handlist of medieval and early modern manuscript and early printed materials in a private assemblage, as reported earlier, I reflect upon the precarious fates of original written materials in their uncertain transmission across the ages and through the hands of different custodians or predators, by turns – not necessarily in that order. The first post in this series described such effects in the Middle Ages, at a center prepared to despoil and dismember, by turns across the centuries, one of its most splendid and illustrated manuscripts. The central case involved the magnificent Royal Bible of Saint Augustine’s Abbey, Canterbury, with partial dispersal or dismemberment at several stages and subsequent attempts to restore the remnants in some fashion.

Perhaps it is one thing for the creator of a monument to re-create it in various ways as the changing centuries might dictate. It may be something else again for others who take the materials into their own hands to decide how to dispose of them, with the operative word being ‘dispose’.

And so, now I turn to the methods of some 20th-century plunderers and distributors of medieval manuscript fragments. Within the Handlist, a few items are identifiable (after the fact) as leaves which passed through the hands of Otto Ege in the fuller form of their former manuscripts.

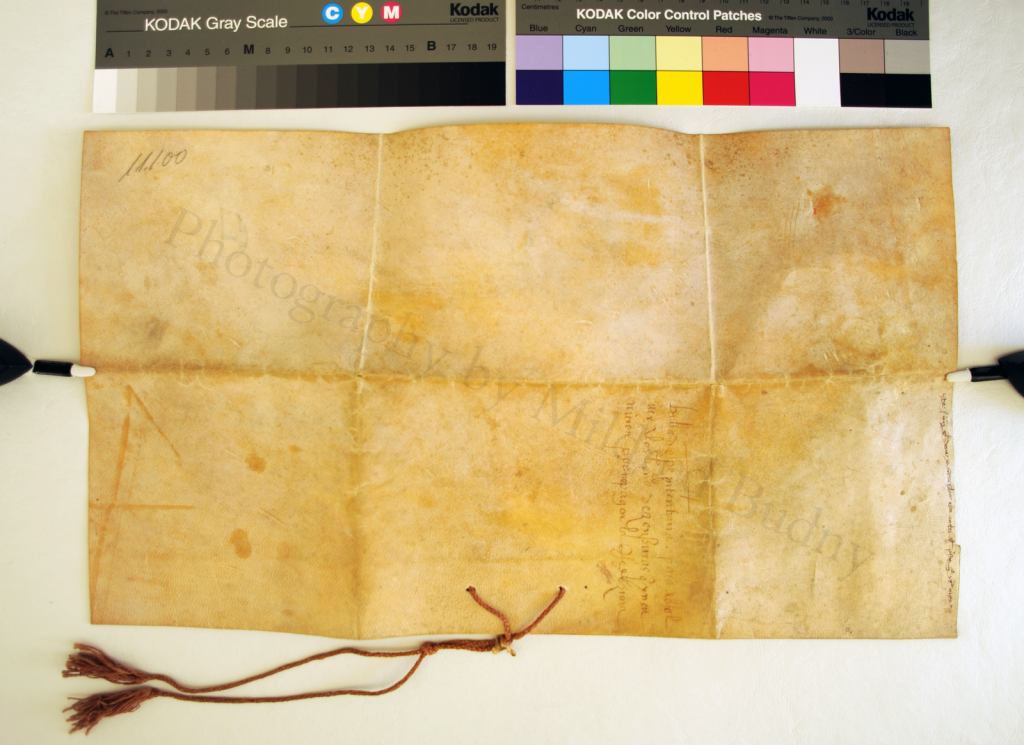

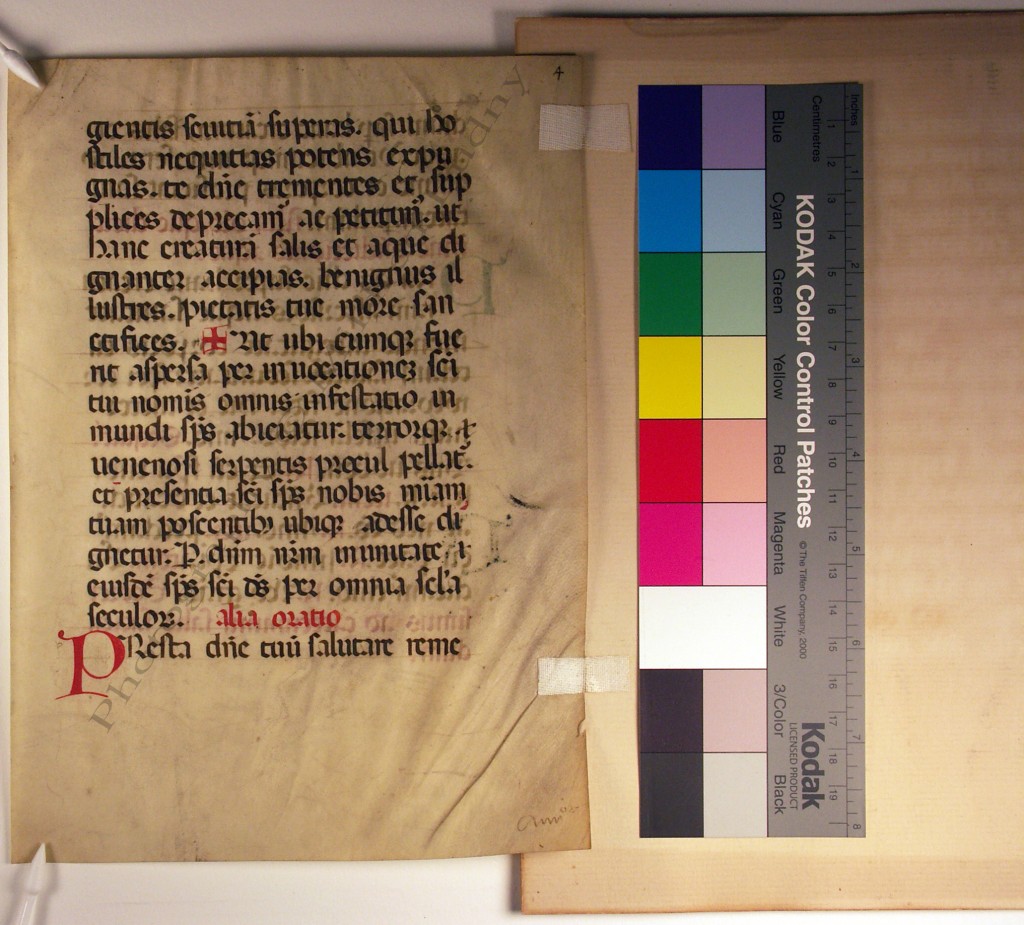

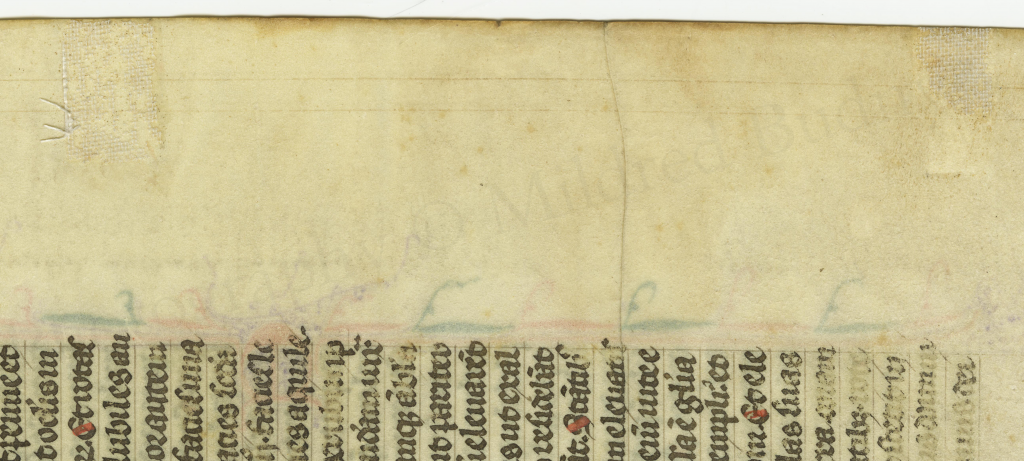

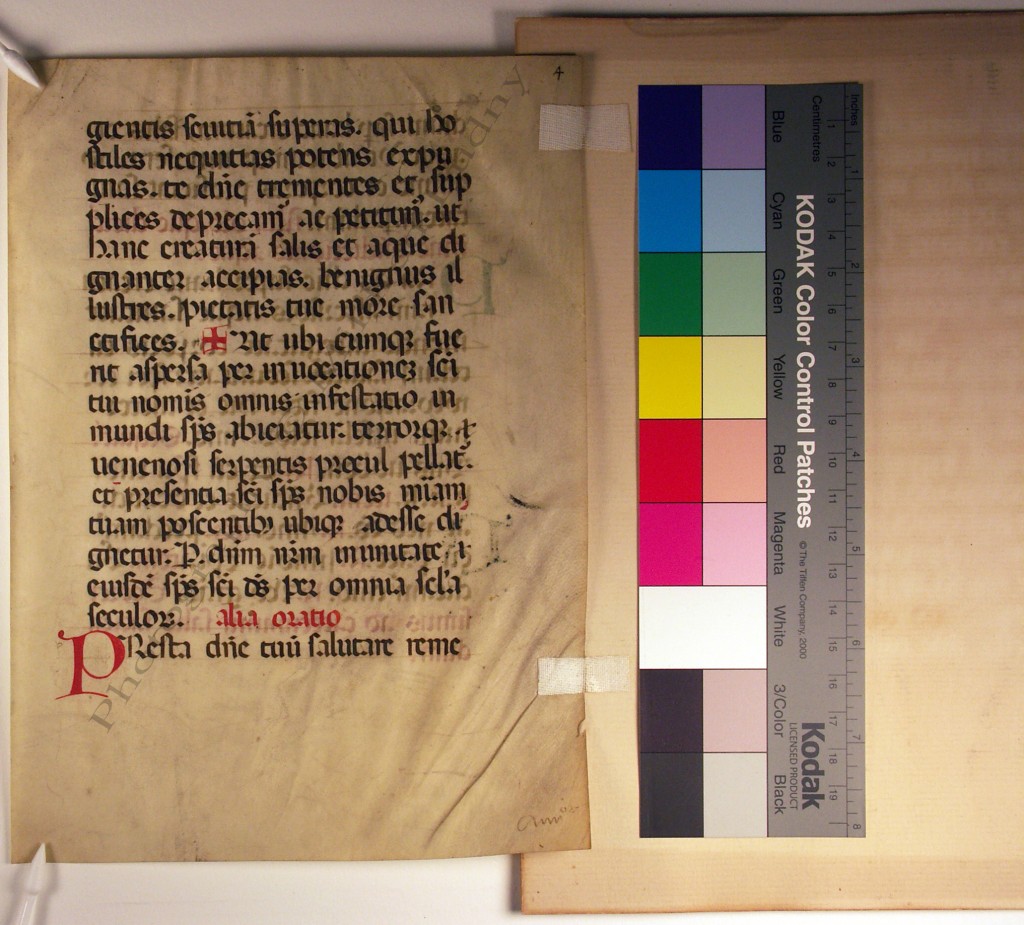

For example, one leaf, which carries the Arabic numeral 4 in black ink on its original recto, was contained within a glass-fronted frame when I first saw it, nearly a decade ago, as part of the initial stage of photographic work on the assemblage (in its state at the time). For conservation, I removed the frame and then photographed the leaf, recto and verso, while still attached to its existing cardboard mat. In consultation with the owner of the leaf, we decided to remove the mat and conserve the leaf separately. Those practices for the Assemblage as a whole, in stages, will be reported elsewhere. Meanwhile, I can show a first photograph (under flourescent lights) of the leaf lifted at an angle from its ‘original’ mat.

Because of my training, and awareness of the importance of respecting the evidence of manuscripts (and other materials), even if, at first sight, the value of specific clues might not be recognized, I have taken care to try to keep them in mind, while my experience might widen into areas which they require for decipherment.

I didn’t know it at the time, but the style of matting itself turns out to be a potentially diagnostic feature in the quest for identifying the fragment, its context, and its provenance. Call it a forensic clue in this complex detective work. Another post will focus upon this leaf, but, for now, we focus upon the clues in question.

A detached folio 4r still attached to a cardboard mat with Ege-style tapes asymmetrically aligned (Budny Handlist 9)

Bits & Pieces, Reassembled

The cumulative contributions are worth celebrating, as we collectively move forward with their clues and directions. Some examples of these contributions (mostly freely available) set the scene, with observations, discoveries, illustrations, references, and suggestions for further discoveries:

Barbara A. Shailor (our Associate)

“Otto Ege: His Manuscript Fragment Collection and the Opportunities Presented by Electronic Technology”

Lisa Fagin Davis (our Associate and former Trustee):

“In Otto Ege’s Footsteps”

“Otto Ege, St. Margaret, and Digital Fragmentology”

“Manuscript Road Trip to Virginia”

“Reconstructing the Beauvais Missal”

Peter Kidd:

“A Newly Discovered Leaf”

“Ege’s 12th-Century Italian Lectionary”

“Ege Leaves at Glencairn Museum” (with specimens of the handwriting of Otto Ege and of his wife Louise)

Scott Gwara (our Associate):

Otto Ege’s Manuscripts: A Study of Ege’s Manuscript Collections, Portfolios, and Retail Trade (a book for sale),

with a survey of the evidence for the acquisition and dispersal of his manuscripts,

including a “Handlist of Manuscripts and Fragments Collected or Sold by Otto F. Ege” (Appendix X).

An important part of these processes of investigation and discovery is the ability to examine the originals, whether in person or by proxy, through images reproduced in print or otherwise. Digital facsimiles of all or parts of their Ege materials are available online for some collections, as here:

The Ege Manuscript Leaf Portfolios in several collections, gathered virtually by the Denison University Library

Fifty Original Leaves . . . From the Otto F. Ege Collection at Case Western Reserve University

Otto Ege Collection in the Public Library of Cinncinati and Hamilton County

Fifty Original Leaves From Medieval Manuscripts (Otto F. Ege Collection) at the University of Minnesota

50 Medieval Manuscript Leaves at the University of Sasketchewan

Pages from the Past: Ege at the University of South Carolina

Massey College Medieval Manus . . . at the University of Toronto.

Examining and comparing these specimens, together with the scattered evidence for the distribution and identification of the sundered portions of the original manuscripts, which apparently survived more-or-less intact into the 20th century before their ‘repurposing’, may help to recognize more of their separated parts. Such is the case here.

Way to Go

More discoveries await recognition, as the news spreads about research and discoveries relating to the dispersed manuscripts and the processes of acquisition, dismemberment, and piecemeal distribution. While deploring the vandalism of monuments of the past, we admire the dedicated efforts to assemble the virtual ‘reconstitution’ of their fragments. At least it is something.

That it is less than perfect, and less than it could have been, is not the responsibility principally of the despoilers who dismembered the materials and failed to record the crucial contextual information as they let the fragments loose onto the world. Orphans by intent. Foundlings by goodwill, dedication, and good fortune. Sometimes, it seems, we find them without notice. Sometimes, it may be, they call out to us.

Lost & Foundlings

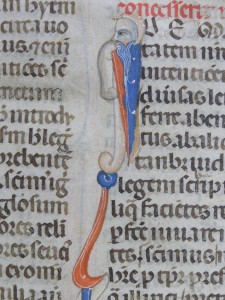

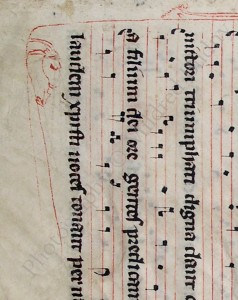

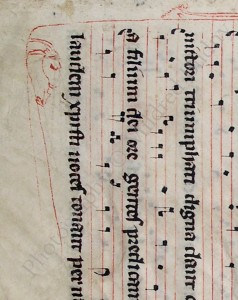

A whimsical creature at the bottom of the page faces the music. Budny Handlist 4

And so, now, as I round out the preparations of illustrated reports on the private ‘Assemblage’ of medieval manuscript fragments and documents, now with a Handlist assigning numbers to the items, the rapidly advancing research on Otto Ege’s manuscripts and fragments by scholars, librarians, catalogers, and book-sellers can enable the further recognition of other stray fragments which came from (or through) his holdings, set loose into the world with little information to record their origins, state their contexts, or signal the survival of any other siblings from the same original volume. Such recognition often comes only in pieces, that is, as we individually or collectively might find the relevant expertise and discover some firmer information about the original whole that may reside in one or another of its other surviving or recorded parts, with a colophon naming the maker.

In some cases, the identification of a stray leaf as having formerly belonged to a known Ege Manuscript might be secured by the continuity of textual sequences between it and another in that book (as listed occasionally here), by offsets of pigment from the formerly adjacent page onto it, or similar clues. In contrast, in some cases, while the processes of research and recovery continue to advance, such specific establishing indicators might not survive, or come yet to light, so that the identification might have to remain tentative, perhaps at least for the time being, or as having belonged to a volume in the same style, by the same hand(s), from the same center at about the same period of production, or the like.

It’s a shame that we have to restore some sense of continuity and context to these ‘waifs’ so laboriously and sometimes haphazardly, at best.

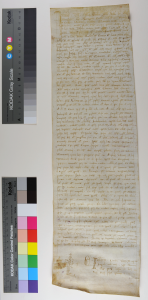

Otto Ege cut into pieces many medieval and early modern manuscripts of various types, dates, and places of origin, for assembly as individual leaves into various unique sets, as with the series of portfolios entitled Fifty Original Leaves from Medieval Manuscripts. Mounted on individual mats, given identifying labels, and numbered in sequence, the selected leaves were placed into boxes and distributed mostly by sale to museums, institutions, and private book-collectors. Only a generic descriptive label, printed on a slip, accompanied each of these individual representatives of a former unique whole. Other leaves from the same manuscripts – the rejected ‘random or rogue’ leaves as described by Lisa Fagin Davis and by Barbara Shailor – were circulated in various ways through gift or sale. Some of those leaves, if they are ‘lucky’, carry brief inscriptions written by Ege or his helper(s) in the lower margins of their rectos. Over time, the ownership and locations of some sets, parts of sets, and individual leaves have changed. The current locations of some of this Portfolio of Fifty and other Portfolios (focusing upon other themes) assembled by Ege are known; some of them have lost some of their individual components. It remains a tedious task for scholars to attempt to pick up the pieces, even if only virtually.

It is an asset that some collections offer digitized views of their representatives of these fragments. The form or appearance of such representatives can vary greatly. Those variations, some cumbersome, merit another reflection or review. Now let’s look briefly at what the individual ‘Orphans’, ‘Waifs’, and Strays’ might bring with them when they come into our view. I think of them as Foundlings, left upon our doorsteps. Here is why.

Babies & Bathwater

Approaches to abandoning babies — human babies, snatched from their birth-mothers and birth-families — can vary enormously, (un-)naturally. Across the centuries, such approaches might range from inexorably casting the new-born, naked, into the mouth of the lair of wolves, at one extreme, to placing them, lovingly, wistfully, at the other extreme, at the entrance of the forum, church, or sanctuary, say at dawn at the beginning of the day’s commerce and traffic, and setting them on to their new, uncertain, course, with a basket or cradle, a tender supply of clothing, a blanket, jewelry of some kind, a toy perhaps, maybe a bit of food, to hope to smooth the safe passage of the living being into the hands and care of strangers, who might be prepared to offer them foster homes or even adoption.

Clues or Clueless

Babies are different, true, from manuscript fragments, but the point is clear. What traces do their occasional owners, masters, agents, or purveyors choose to hand on, or hand over, to the adoptive homes or ‘adoptive agencies’ so as, perchance, to allow for some awareness of the parentage, ‘birth certificates’, genetic tendencies, family contexts, and other relevant information about their origins and upbringing?

In a nutshell: Not Much, in many cases. Ah well, sometimes the results may be due to negligence, indifference, or haste, but in some cases the effects as well as the methods appear to resemble the actions of ‘criminals’ who have the sense to destroy as much evidence as possible, take the money, and run. At ‘best’, the conveyers of altered, fragmented manuscript materials might be little aware of how much forensic evidence can reside in the substances, surfaces, and accretions of those materials.

Forensics in Manuscript Studies

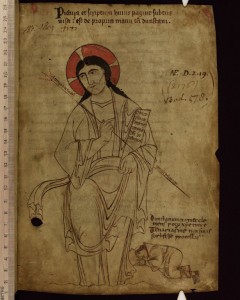

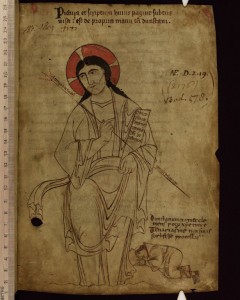

Saint Dunstan’s Classbook, MS. Auct. F. 4. 32, folio 1r, tenth century. Photo: © Bodleian Library, University of Oxford (2015).

Permitting those seemingly insignificant traces of many kinds to remain in place (provided, for example, they do not actively harm the artefacts) may allow them to be observed, recognized, and deciphered by appropriate expertise.

An example of such discoveries applied to a renowned early medieval manuscript, or rather composite manuscript (assembling into one volume several different portions containing different texts, languages, dates, places of origin, annotations, scribbles, and other alterations), can be observed for the so-called ‘Classbook’ of Saint Dunstan and its ‘signed’ frontispiece image. For centuries that image has been believed — wrongly, it turns out, through forensic examination – to be the saint’s self-portrait. Yet it does have his own ‘autograph’ in the form of a prayer in his own hand and in his own name, added to the drawing of a monk before Christ made by a different scribal artist. Appropriation may be a sincere form of flattery, but it does not necessarily constitute (when detected) the authentication of the appropriator as the creator of the artwork in full.

‘ID Bracelets’ and ‘Identity Marks’

In the absence of explicit testimony, both within or upon the fragment itself, it can be appropriate or expedient to turn to forensic and other forms of evidence, implicit or indirect. Such testimony, when properly recognized, can work wonders.

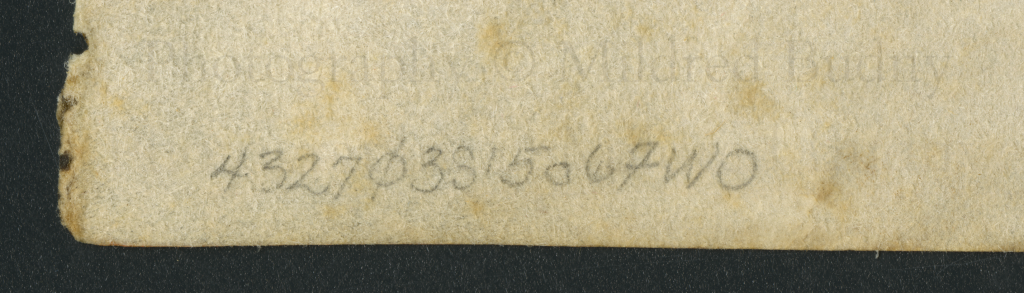

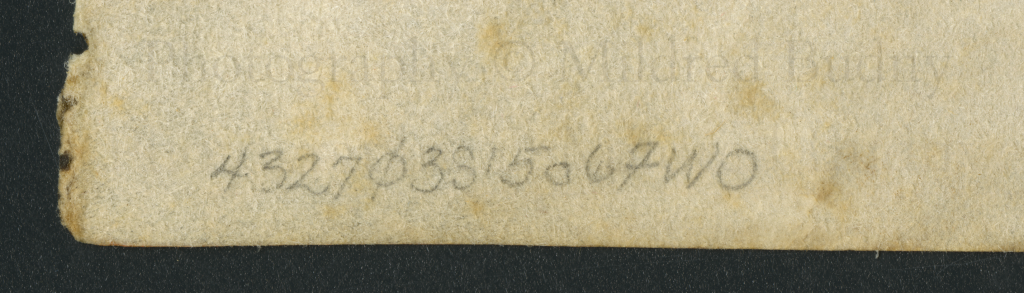

The ‘Seller’s Tell’

The ‘Identity Marks’ or tags made by many sellers of manuscript fragments may take distinctive, recognizable forms. The styles and methods may be telling. The statements may serve as concise cues identifying the item in some way, say with a verbal description or an inventory number. Some may function as cryptic notation, perhaps including codes denoting the expected price or price-range in a manner obvious to the seller but not the buyer. When entered in pencil discreetly at the bottom of a page, the tag might seem unobtrusive, possibly erasable without much trace, and readily ignored — especially when covered by the overlap of a mounting frame.

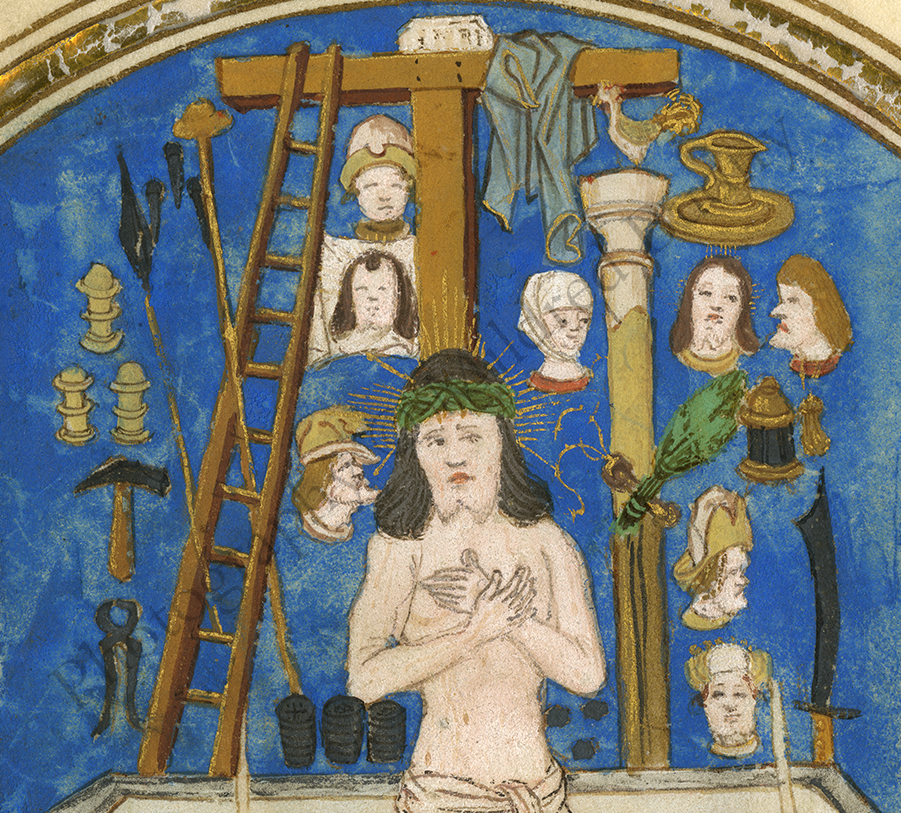

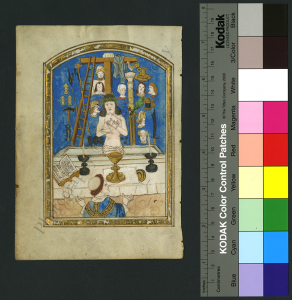

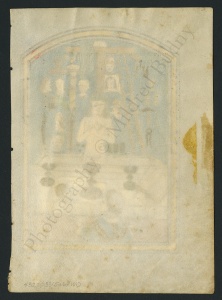

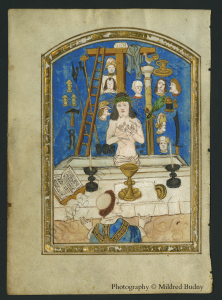

Exhibit A

A cryptic form of seller’s mark appears in the cryptic string of numbers and letters on the recto of the leaf with the Gregory Mass, purchased by its present owner from a major international bookseller in the 1990s.

Seller’s Mark in Code (Budny Handlist 13)

Exhibit B

A different form of Seller’s Mark characterizes the approach to marking many of the ‘Rogue’ leaves dispersed from Otto Ege’s collection. Not all such leaves carry this form (which has some variations). But where they do, they may give significant, if compacted, information besides the price.

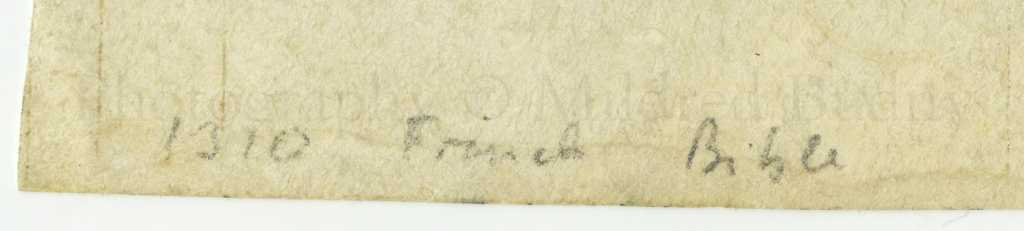

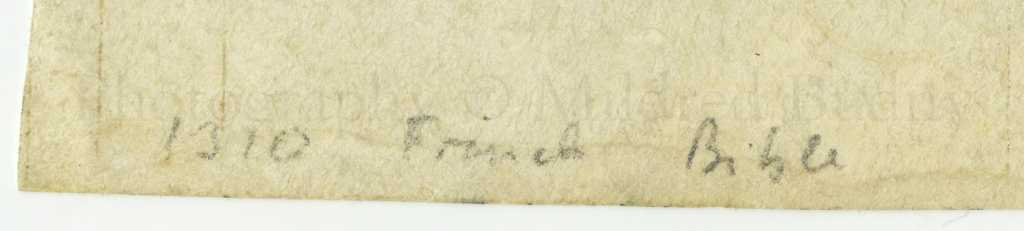

A simple form, reduced to the presumed date and genre of book, labels a pocket-sized leaf with text from the Book of Exekiel as ‘1310 French Bible’, tout court. By itself, the inscription might hold little promise, but a detailed comparison indicates the identity of the hand and the conditions of the ‘Tagging’.

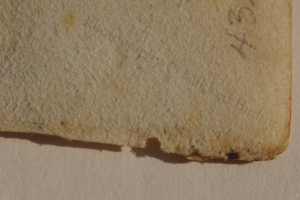

Pencil inscription (Budny Handlist 7)

The discovery of the connection of this fragment to Otto Ege’s collection and its former manuscript had to await the recent research on the ensemble of manuscript materials as a whole. It is both fortuitous and beneficial that my ongoing research on the ensemble and its components coincided with the plenitude of reports of rapidly advancing discoveries about many of Ege’s dispersed fragments, their current locations, their marks of Ege’s handling, and their interrelations.

Various of the reports listed above identify and illustrate these marks, including specimens of Ege’s handwriting, the characteristics of his his mats for many of the leaves both within and beyond his Portfolios, and his form and uneven style of mounting tapes for the leaves and their mats. More about those mounting tapes in a moment, but first, a closer look at another pencil inscription which clinches the deal.

Exhibit C

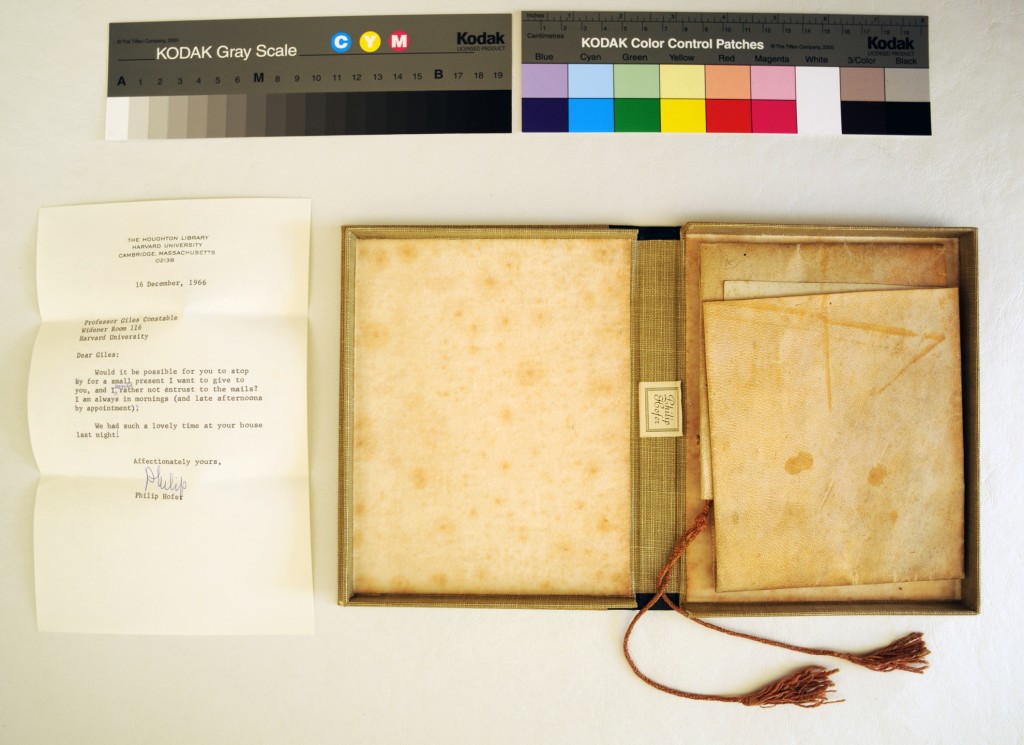

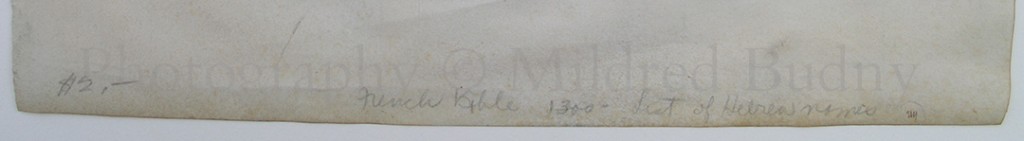

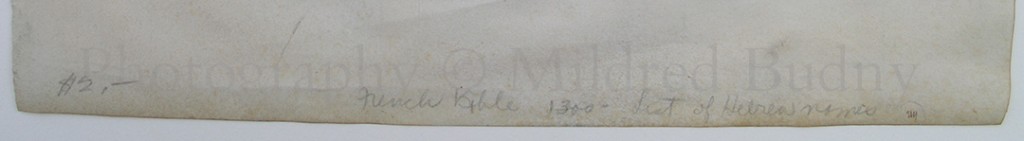

One leaf which, according to his recollection, the present owner purchased at the shop of the Cleveland Museum of Art in or about 1953, carries on its recto the price of ‘$2.—’ and, spaced at an interval to the right, the brief description of the item as ‘French Bible 1300 – List of Hebrew names’. The owner purchased the leaf on its own, unmounted, and without any further description. A future post will tell more about this leaf and its former manuscript, a massive Bible now dispersed in many directions and collections, with confusingly inconsistent seller’s and cataloguers’ descriptions.

‘List of Hebrew Names’ in a ‘French Bible’ of ‘1300’, price ‘$2’, purchased circa 1953 at the Cleveland Museum of Art shop (Budny Handlist 8)

Exhibit D

A leaf now identifiable on other grounds as an Ege ‘Rogue’ Leaf appears to have a pencil inscription characteristic for the varied genre, starting with a price of ’10 –’ (presumably in dollars), followed perhaps by some more information entered at the same time, by the same hand, and in the same medium. However, the subsequently applied masking tape, with unevenly torn edges, which served to adhere the leaf to a mat by 1959 when the leaf was given to its present owner (and which has recently been removed in conservation) also mostly masks (presumably) the rest of an inscription. When the leaf was conserved recently, it was decided to allow the masking tape to remain, as a record of the history of the leaf. And so the rest of the inscription (if any) could remain for future revelations.

Pencil Inscription Partly Veiled (Budny Handlist 12)

‘Baby Blankets’, ‘Swaddling Clothes’ & ‘Cradles’

Mats & Mounting Tapes

Some telling, or ‘diagnostic’, features might seem insignificant at first glance, but they could provide evidence of the hand at work. Where other clues have been removed, such traces may be essential and solitary in their attestations as witnesses. And so they might have to testify (see above) as Tips of Icebergs. Let us consider the often dismal evidence of mounting tapes, that is, the adhesive tapes found on manuscript fragments — which, in some cases, they not only accompany, but also enslave.

At most glances, such tapes might easily be ignored. Who cares? Well, some of us do, although not everyone has to. It’s enough to recognize that someone might find them worth examining. To forensic examination, their features can sometimes reveal significant testimony.

Exhibit E

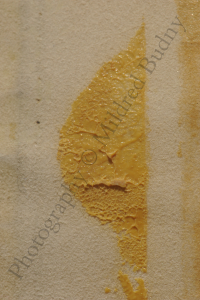

A simple example can set the scene. Non-archival masking tape is sometimes readily employed in framing materials, presumably for its convenience, ignorance about its interactive characteristics, and awareness that its presence will be hidden under the mat or the edges of the frame. In recent conservation, the removal of the frame, glass, and mat from a detached leaf of an 11th-century Giant Latin Bible purchased in 1951 in Florence, Italy, and subsequently framed in the United States has revealed some strips of tape, with unevenly torn edges.

Masking Tape added after 1951 to the reframed fragments of a single large-format 11th-century leaf (Budny Handlist 1)

Exhibit F

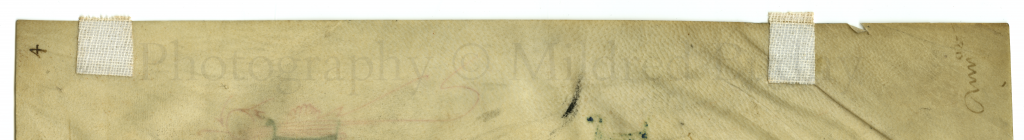

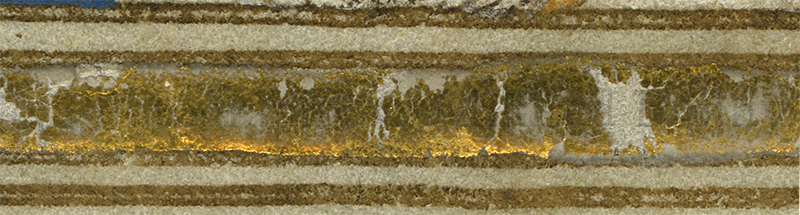

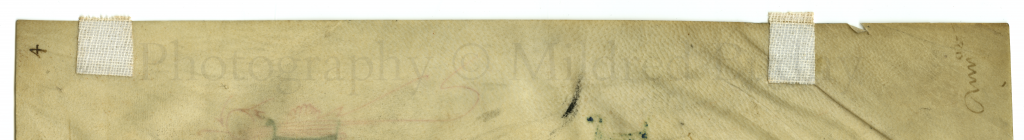

Now we turn to examples of Ege’s mounting tapes within the Handlist. The pair of unevenly cut and unevenly placed mounting strips of gauze tape glued along one long side of ‘Folio 4’ of Handlist Number 9 (shown above still attached to its former mat) is representative of his style of application, given the cases already attested.

On various grounds, even apart from the tapes, this leaf can be identified as one of Ege’s ‘reject’ leaves from a manuscript deployed among the Fifty Original Leaves. Known Ege examples are illustrated, for example, here and here.

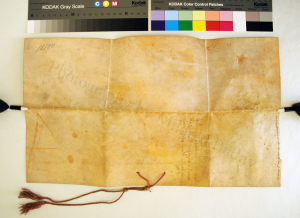

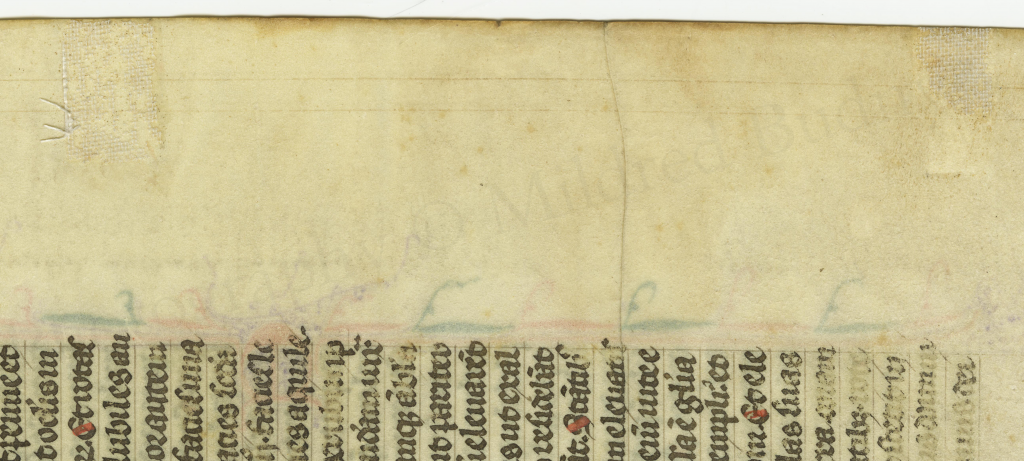

A detached Folio, which carries the Arabic number ‘4’ in black ink at the top of its recto (inscribed on the leaf while it still stood in place in its former manuscript), retains its asymmetrically placed whitish gauze mounting tapes attached to the outer edge. The non-archival cardboard mount for this leaf, to which the tape strips formerly adhered in the form of hinges, has been detached during recent conservation, and is kept separately. On the mat, the leaf was mounted with its original recto turned to the verso.

The type of tape and its style of placement corresponds with known Ege methods. A ‘stroll’ or ‘scroll’ through the digital facsimiles of mounted Ege materials (as in the Massey College Medieval Manus . . . series) reveals many cases of such mounting tapes, not infrequently positioned asymmetrically. Same as here:

The outer edge of a detached Folio ‘4’ recto and its 20th-century ‘Ege’ mounting tapes (Budny Handlist 9)

Exhibit G

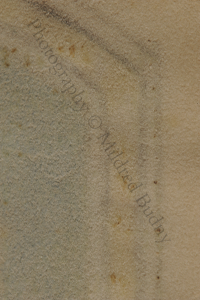

In another case, such mounting tapes were removed some time ago by some agent or other, without record. Similar traces appear, for example, here.

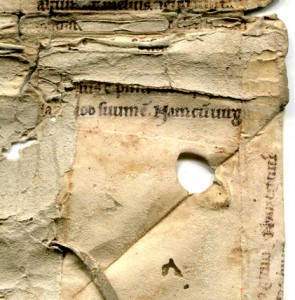

Remnants of a pair of gauze mounting tapes (Budny Handlist 7)

Fortunately, it turns out, the gummy substance resisted the removal of all trace of the tapes, whose material, form, and alignment are familiar to observers of Ege’s methods of mounting the detached leaves, whether for his Portfolios or other forms of dispersal.

Even so, many of his dispersed leaves ‘rejected’ for inclusion in the Portfolios have wandered without the addition of mats. In their cases, the brief (or briefest) pencil inscriptions might have to serve alone as a clue to his intervention in the history of the artefact. In other cases, Ege’s dispersed leaves might have to roam without any of his recognizable marks, until, say, the identification of the text, the scribe, the workshop, or some other means of connection with the original manuscript might be accomplished. Meanwhile, every step forward, by whatever clues, may count as progress.

Next we report the discoveries for another detached ‘Ege Manuscript Leaf’, which has wandered on its own, without label, identifying inscription, or other explicit mark of Ege’s ownership. For such a case, other detective methods also are required.

A Virtual ‘Orphanage’

How the different ‘Foundlings’ among manuscript fragments might sometime find a proper, albeit virtual, home so as to acknowledge, to record, and to welcome their familial connections in former whole manuscripts as a form of ‘genealogical recovery’ remains to be determined in the concerted quest in various centers to establish and to foster such projects. While they find their fuller footing, with larger institutional supports, we will turn to the next report on our findings.

Next stop: ‘A New Leaf from Ege Manuscript 41’, from a different collection.

We welcome your comments, questions, and feedback. Please leave a comment or Contact Us.

*****