A New Leaf from ‘Otto Ege Manuscript 14’

September 6, 2015 in Manuscript Studies, Photographic Exhibition

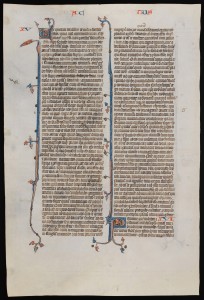

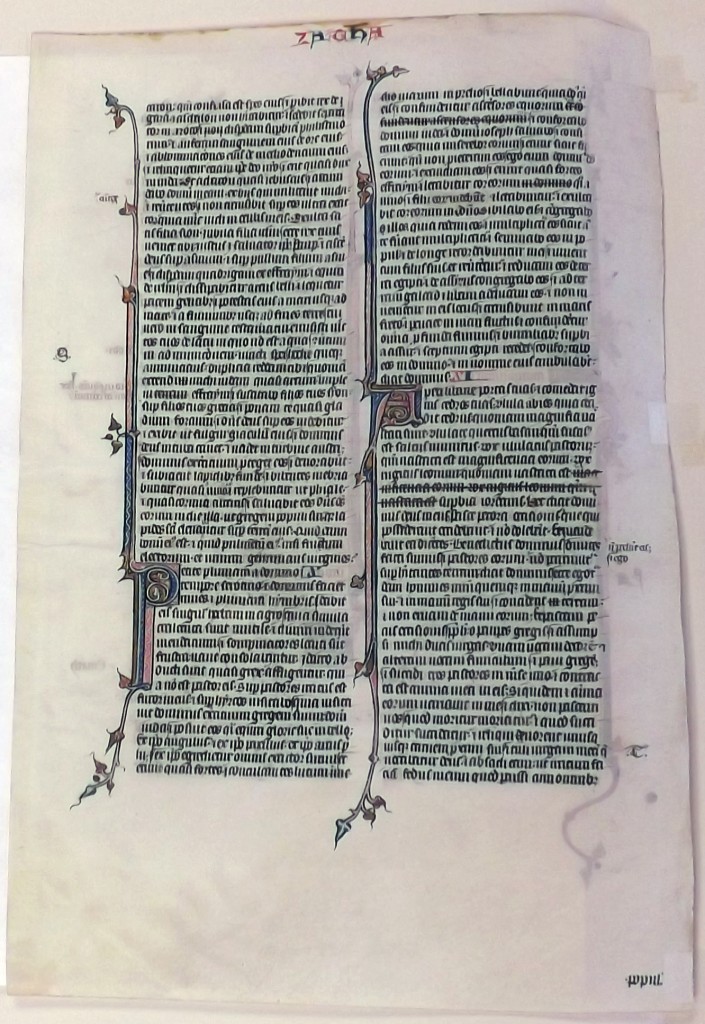

Part of the ‘Interpretation of Hebrew Names’

from a 50-line Lectern Bible

in the Vulgate Version

Budny, Handlist Number 9

A Leaf From ‘Otto Ege Manuscript 14’

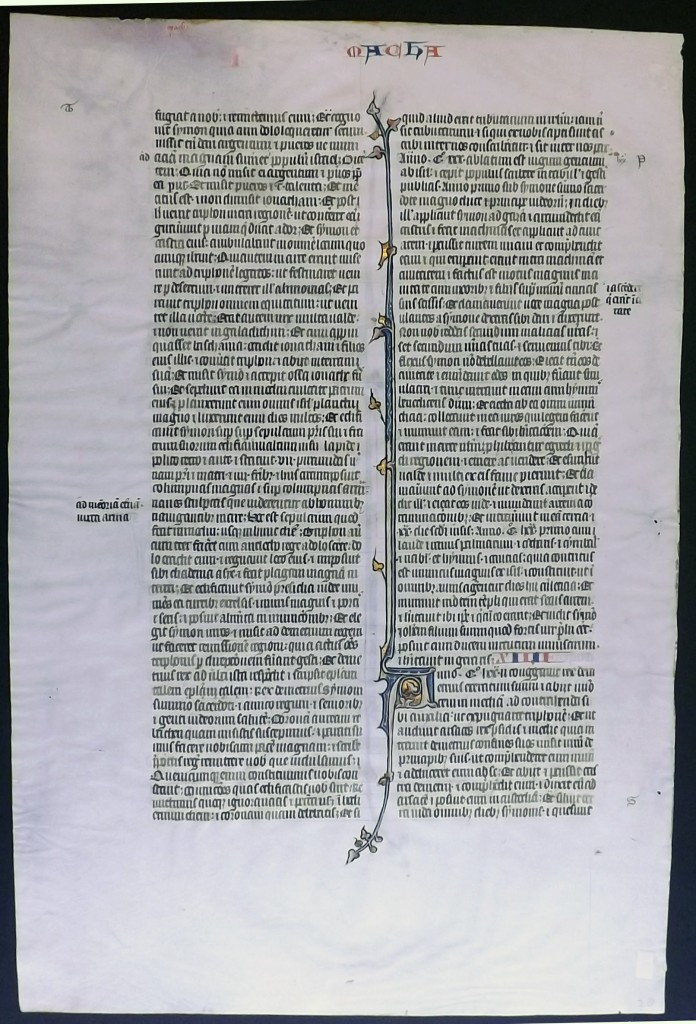

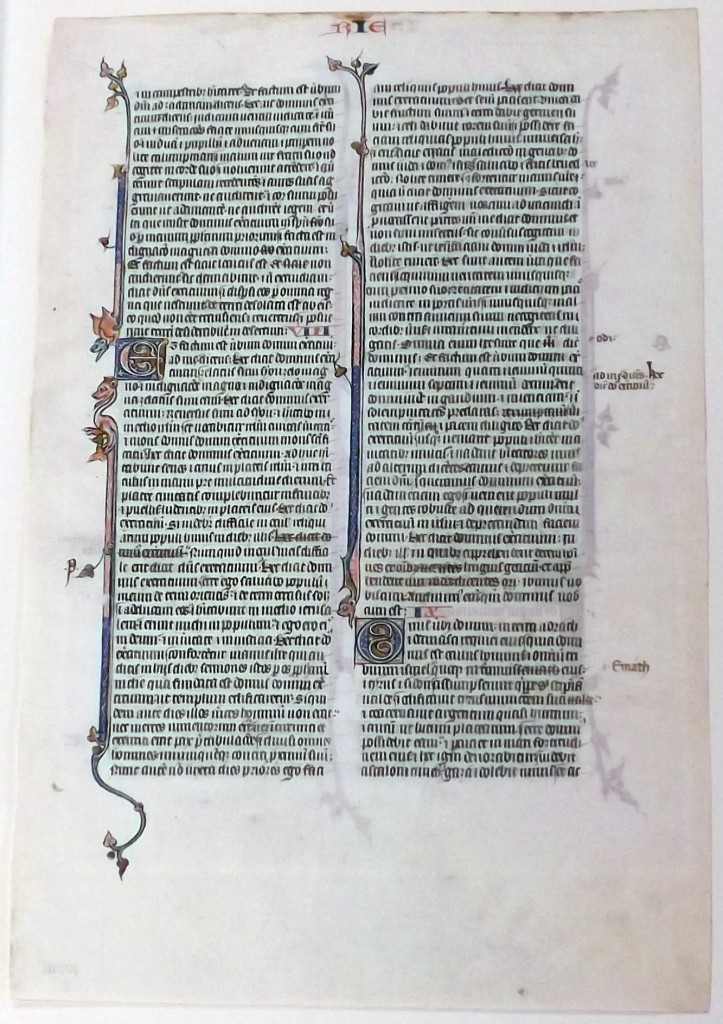

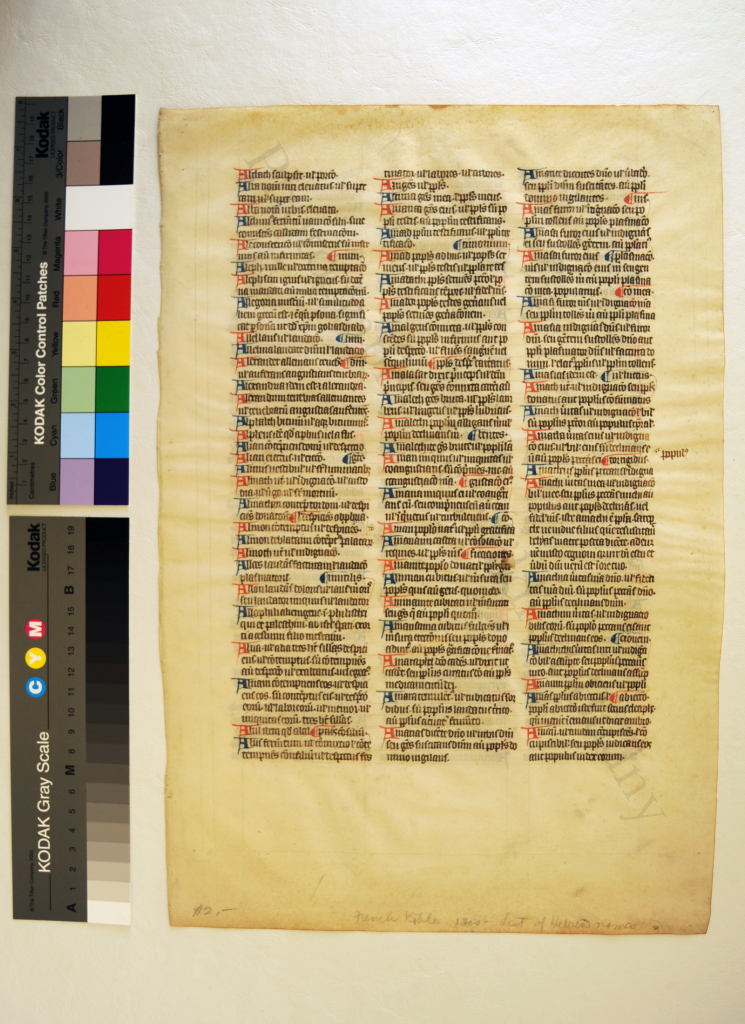

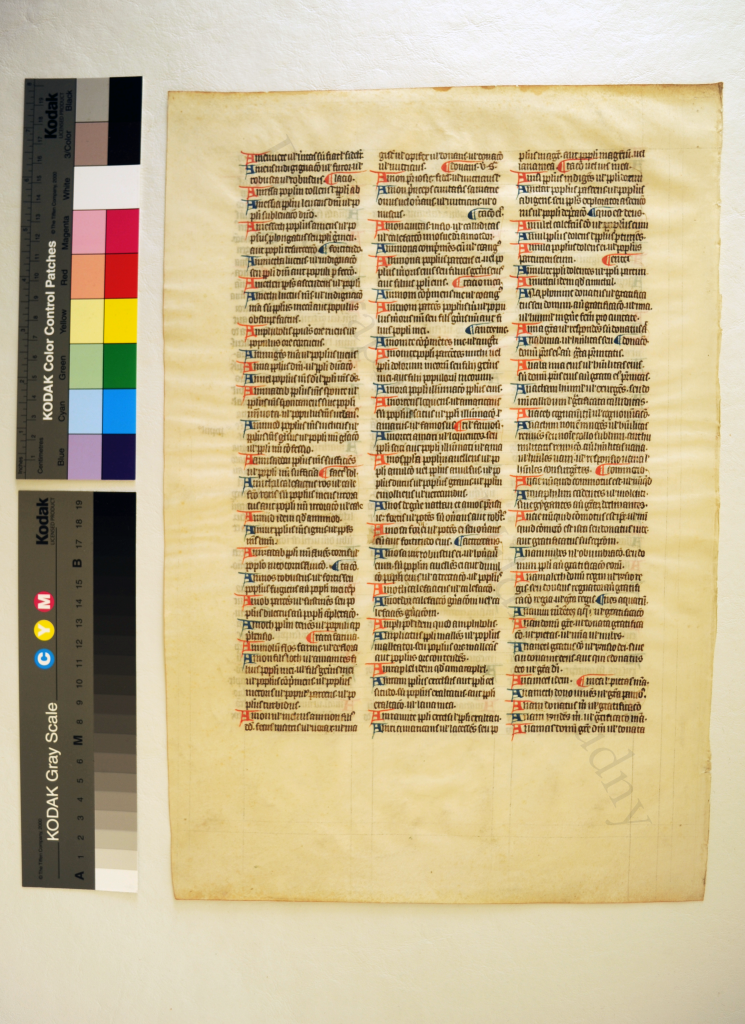

Alcath – Ananias in the A-Group

From the Interpretationes Hebraicorum Nominum

In the partly alphabetized Version beginning Aaz Apprehendens (or a Variant thereof)

At the end of a large-format Bible used for lectern reading

Circa 312 × 212 mm <written area circa 225 × 157 mm >

Triple Columns of 50 lines written in Gothic Formata bookhand

Produced probably in Flanders or Northern France, circa 1325

In our series on Manuscript Fragments, Mildred Budny examines some leaves dispersed into various collections, both private and public, through the methods of Otto F. Ege. Earlier posts on those leaves considered Lost and Foundlings, A New Leaf from ‘Otto Ege Manuscript 41’, and A New Leaf from ‘Otto Ege Manuscript 8’. Later posts considered A New Leaf from ‘Otto Ege Manuscript 61’ and New Leaves from ‘Otto Ege Manuscript 51’.

Now we focus on a large-format leaf which, despite its relatively unembellished contents, formerly belonged to a large-format single-volume Bible amply endowed with decoration, illustrations, and glittering gold.

[Posted on 6 September 2015, with updates. The updates reflect access to the sales catalogue of 29 November 1948, with thanks to Judith Weston of Sotheby’s and to Sotheby’s Inc. for permission to cite it here, and the resulting consultation of the resources both online and in the card indexes of the Index of Christian Art. Newer updates reflect access to the Maggs Bros, Catalogue 1059 (1985).

More recently, the announcement that (after earlier sales from that collection), the residue of manuscript materials in the possession of Otto F. Ege’s family has been purchased by the Beinecke Library at Yale University in November 2015 encourages the anticipation of more revelations about surviving leaves from the dispersed manuscripts, including this one. More recently still, the preparations for the Research Group Symposium on ‘Words & Deeds’ in March 2016, to include a session reporting on this new trove, have allowed us to glimpse more pages from the same noble Lectern Bible. With permission, the Posters and the Program Booklet for the Symposium can show some of them, both from the Lectern Bible and from other ‘Ege Manuscript’ materials.]

We unveil another detached leaf, privately owned and previously unknown, from one of the very many manuscripts which Otto F. Ege (1888‒1951) dismembered for dispersal, mostly by sale. Some of its leaves were dispersed individually as specimens in the different sets of his early Portfolio edition of Fifty Original Leaves from Medieval Manuscripts, Western Europe, XII‒XVI Century, issued circa 1950.

In this Portfolio, each specimen from the one manuscript appeared as Leaf Number 14, framed in a mat, provided with a uniform printed descriptive caption, and placed in the company of single leaves from other manuscripts similarly presented. Other parts of the same book circulated differently, as the so-called ‘Rogue Leaves’ or groups of leaves (‘Residuals’) discharged from Ege’s corral. The New Leaf is one such ‘Rogue’.

Many of the ‘Rogues’ roamed as single leaves, like this one. Its provenance, reaching its present owner by purchase already in late summer of 1953 at the Cleveland Museum of Art gift shop, establishes that it was a single ‘Rogue Leaf’ from the beginning of its travels apart from its siblings in the volume. Some other leaves outside the Portfolio traveled in ‘Residual’ Groups of 2 or more leaves, sometimes with regroupings which further separated those outcast siblings into smaller groups of ‘Orphans’ (that is my term), which sometimes turned into Single Leaves.

By definition, perhaps, those new Single Leaves could then count as ‘Rogues’. Should we consider those redistributed leaves as ‘Changelings’?

A spectacular case resides in MS 223 in the Schøyen Collection, perhaps as the dedicated result of gathering together portions of the book sold by different vendors at various times or maybe as the purchase from a single lot (a Big Lot). Some accounts say that that portion comprises 105 leaves, others say 210. I have not been able to ascertain which.

As its website description declares, ‘It was a tragedy in art history that this grand and rare lectern Bible was broken up by speculators. It has been restored towards its former greatness as far as possible. Anathema on whoever dare to break it up again!’

The New Leaf

The leaf is Number 9 in my Illustrated Handlist of a group of medieval and early modern manuscripts, documents, and early printed materials. As written, it turns the hair side of the animal skin to the recto and the somewhat whiter flesh side to the verso. The unevenly trimmed inner edge, running more-or-less along the former fold line or gutter of the sheet, retains some of the notches at the former stitching line and, apparently, slight amounts of the connected leaf of a former bifolium, or pair of leaves from a single skin. So we could guess that this leaf used to belong to a bifolium.

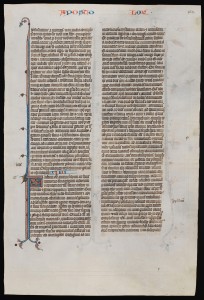

The Seller’s Tell

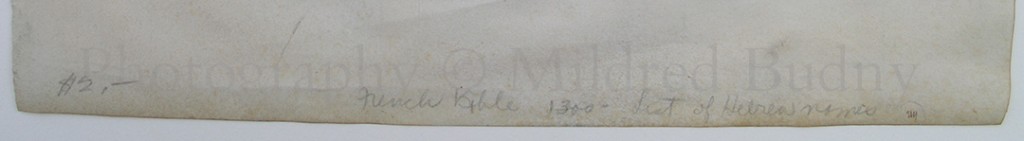

At present, the leaf measures circa 312 × 212 mm, with a written area of circa 225 × 157 mm and script in a formal Gothic bookhand. Across the bottom of its recto there is spaced an inscription in pencil, written by a single hand, declaring its price and description: ‘$2.__ French Bible 1300 – List of Hebrew Names’. You could be forgiven for thinking that this statement is only quaint and perhaps insignificant.

At present, the leaf measures circa 312 × 212 mm, with a written area of circa 225 × 157 mm and script in a formal Gothic bookhand. Across the bottom of its recto there is spaced an inscription in pencil, written by a single hand, declaring its price and description: ‘$2.__ French Bible 1300 – List of Hebrew Names’. You could be forgiven for thinking that this statement is only quaint and perhaps insignificant.

After all, that’s what I thought, too, years ago, when I first set eyes on the leaf itself, in the flesh. Its other features captured my attention, in terms mainly of the text and its layout. To start with, that is. But then, tending to them as well as to the wider picture of the former manuscript and its context across time, insofar as we can reclaim it, this inscription emerged as a crucial piece of evidence.

Triple Treat

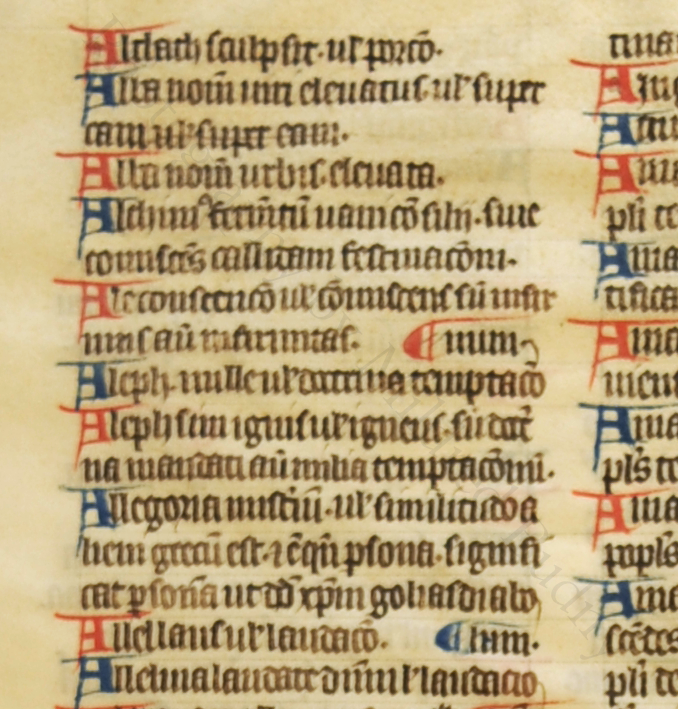

In triple columns (‘a’–’c’) of 50 lines, the leaf contains part of the A-Group of a version in Latin of the Interpretationes Hebraicorum Nominum (‘Definitions of the Hebrew Names’), a partly alphabetized glossary giving etymological explanations for many of the proper names, or terms, to be found in the Vulgate Bible, transliterated from Hebrew, Aramaic, or Greek. This portion of the glossary starts with the entry for Alchath or maybe Althath (the territory mentioned in Joshua 19:25) and ends with, or within, the entry for Ananias (the name for several men in the New Testament), interpreted as donum gracia domini uel donata / [. . . ?]’. Ranging widely from prominent to obscure, the terms include Aleph, Alla, Alleluia, Allegoria, Alexander, Alexandria, Amalech, Amen, Amon (with 5 different entries), Amos (with 2), and more. The individual entries range in length from 1 or 2 lines to as many as 8 (in lines rc27–34).

Each glossary entry or item starts with the lemma (the name or term) to be defined, presented in transliteration. Set at the beginning of the line and highlighted with an enlarged 1-line initial in red or blue pigment (alternating in color from entry to entry), the lemma is followed by its definition, or sometimes by variant definitions, as with Allel [sic] = laus uel laudacio (‘Alle [means] ‘praise or commendation’) in line ra15. There is no special distinction for the openings of the different alphabetical groups starting with AM and AN, perhaps in a uniform treatment of the A-Group as a whole.

Each glossary entry or item starts with the lemma (the name or term) to be defined, presented in transliteration. Set at the beginning of the line and highlighted with an enlarged 1-line initial in red or blue pigment (alternating in color from entry to entry), the lemma is followed by its definition, or sometimes by variant definitions, as with Allel [sic] = laus uel laudacio (‘Alle [means] ‘praise or commendation’) in line ra15. There is no special distinction for the openings of the different alphabetical groups starting with AM and AN, perhaps in a uniform treatment of the A-Group as a whole.

Some initial letters have cue or guide letters, written discreetly in ink in small script in the space indented for them, to direct the form of the letter for insertion in the different pigments. Their position within the inset area allowed the completed form of the initial letter to stand over, and mostly to obscure, the cue letter. But not entirely, as with the A beginning the recto.

Usually the entries span one or two lines, but some extend further, in more detailed explanations. Many definitions spill over into the available space at the ends of the preceding or the following entries, so that some lines contain parts of two different entries.

Running On and On

Within such lines, the intruder is preceded, and framed, by an emphatic C-shaped 1-line paraph-sign which has a long horizontal top extending above most or all of its letters, sometimes even farther (in rc3 and va3) into the outer margin or intercolumn. These brackets alternate in color between red and blue pigment, adding to the colorful effect of the blocks of text.

For clarity, the two different forms of run-overs can be described as running either below or ahead. In this manuscript, a thin curved line in ink traces a path upward or downward from the end of each line which runneth over, and then stops at the end of the relevant line with the remainder, so as to indicate directly the direction in which to seek the completion of the entry. Usually that path involves the short span between one line and either the next one or the previous one. Sometimes it involves a longer course, of 3 or even (in rc43>40) 4 lines.

These are subtle features, perhaps, but helpful for the reader trying to find the way through densely packed columns of definitions for curious words, perhaps the more so when the transliterations transmitted across time, manuscripts, and different copyists could themselves garble the intentions. That the copyist of this leaf had some difficulties in the transcription can be seen in some mistakes corrected by several means, including the wrong run-ahead in line ra48 (crossed out with a horizontal line through its letters) and the omitted word populus placed in the margin to the right of line rc24, with an identical pair of signes-de-renvoi (/..) placed above that word and above its required position within the line.

A mess, huh? That’s nothing compared to the problems that face efforts to reconstitute, albeit virtually, the leaves dispersed from the manuscript.

Ege Manuscript 14

This leaf belonged to the large-format manuscript which came to be distributed in isolated specimen leaves as Leaf 14 within the Portfolio of Fifty Original Leaves from Medieval Manuscripts, Western Europe: XII–XVI Century assembled by Otto F. Ege circa 1950. In Scott Gwara’s printed Handlist of Manuscripts Collected and Sold by Otto F. Ege — Appendix VIIII (pages 106‒107) in Otto Ege’s Manuscripts (2013) — the manuscript is Ege Manuscript Handlist Number 14 (pages 121–122), attributed to ‘Flanders (possibly France), c[irc]a 1325’.

The nature of the Portfolio, its edition, its methods and date-range of assembly, and the present locations of some of its 41 or more sets (counting those both numbered and unnumbered), are described in our recent posts on

- Lost and Foundlings

- A New Leaf of ‘Otto Ege’s Manuscript 41’ (part of the Dialogues of Gregory the Great)

- A New Leaf of ‘Otto Ege’s Manuscript 8’ (part of the Procession for Palm Sunday for Singing Nuns)

[And now also on

- A New Leaf of ‘Otto Ege’s Manuscript 61’, from a different Ege Portfolio

(part of Exekiel from a 32-Line Latin Vulgate Pocket Bible from France)]

There you can find references and links to many useful studies, still in progress, about Otto Ege’s manuscripts, the discovery of their remnants, and their piecemeal recovery, at least in virtual form.

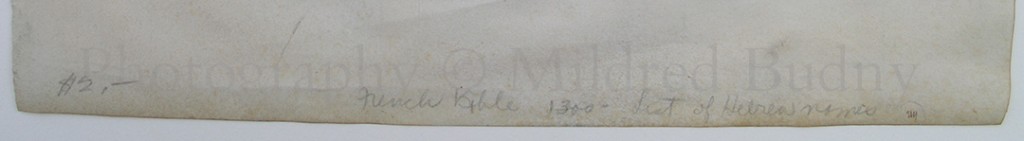

A dedicated website for the Portfolio in question gives a list of the current locations of its sets so far identified (now up to 30 sets). For 13 of the Portfolio sets, this site also shows images of the leaves, usually both recto and verso, with transcriptions and/or identifications for some of their texts. Some collections show their own images, which sometimes includes the recto or verso not included in that Portfolio website. My list here in a preliminary reconstruction of the identified remnants shows those links insofar as I have been able to discover them.

Besides the individual leaves distributed in the 41 (or perhaps more) individual albums or sets of the Portfolio (the locations for 30 of which are currently known), some other leaves have circulated alone or in the company of some other leaves from the manuscript, sometimes also in the company of other leaves from other Ege manuscripts.

In His Own Words

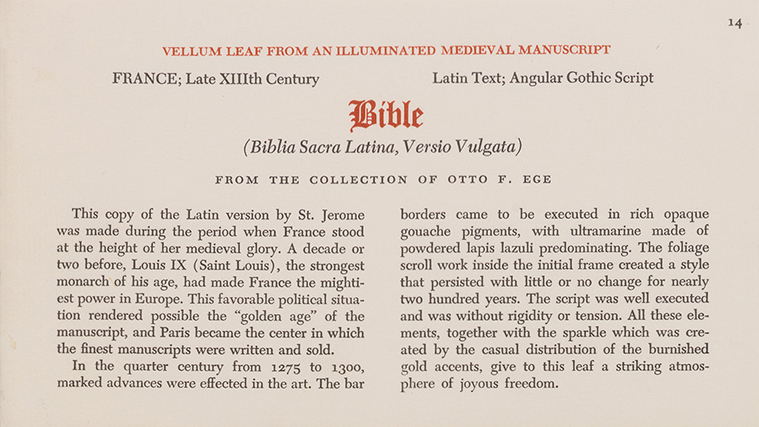

Ege’s printed caption for Leaf 14 does not tell us much about the book itself. Its heading offers the title of ‘Bible (Biblia Sacra Latina, Versio Vulgata) from the collection of Otto F. Ege’, the assignment of origin as ‘France; Late XIIIth Century’, and the identification of contents as ‘Latin Text; Angular Gothic Script’. Here is what he had to say:

Caption for Portfolio Leaf 14. From the Collection of The Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County. Reproduced by Permission

‘This copy of the Latin version by St. Jerome was made during the period when France stood at the height of her medieval glory. A decade or two before, Louis IX (Saint Louis), the strongest monarch of his age, had made France the mightiest power in Europe. This favorable political situation rendered possible the “golden age” of the manuscript, and Paris became the center in which the finest manuscripts were written and sold.

‘In the quarter century from 1275 to 1300, marked advances were effected in the art. The bar borders came to be executed in rich opaque gouache pigments, with ultramarine made of powdered lapis lazuli predominating. The foliage scroll work inside the initial frame created a style that persisted with little or no change for nearly two hundred years. The script was well executed and was without rigidity or tension. All these elements, together with the sparkle which was created by the casual distribution of the burnished gold accents, give to this leaf a striking atmosphere of joyous freedom.’

Even by Ege’s standards for his Portfolio, in which the brief captions could, given the chance, provide some information specific to the case in point (as with Leaves 8 and 41), this description seems unusually skimpy. No: worse. Given the monumentality and beauty of the manuscript, this caption is downright paltry. On a par with the desecration of the book itself.

No offense to the genre of enthusiastic exhibition captions! But not everyone who writes such glowing descriptions — which focus, say, on the gleam of gold in its ‘casual distribution’ (as if its application was a casual, carefree operation) and the richness of ‘lapis lazuli’ (or is it ‘ultramarine’?), rather than on the rich complexity of the leaf itself and its context, including its whole manuscript — has intentionally cut up the book itself so as, among other things, to obscure, fragment, disperse, and outright destroy much of its evidence. In such circumstances, the caption accompanying individual detached leaves would have, presumably, a greater burden to represent its specimen more precisely, even when concisely.

Which brings me back to the caption. Which doesn’t help much. The caption does not count as a good exchange for the disservice done to the monument. Without the evidence of his pencil inscription on the New Leaf (shown here), who might guess at first that it belonged to this book, or anyway to one of Ege’s books? That recognition takes other contextual expertise, and the ability to apply it where the evidence directs.

For that confirmation, as well as for information about other aspects of the book as a whole, we must turn to the sales catalogues for the book or parts of it, and to the pages themselves of the remnants, and to whatever else we might piece together. The challenges of puzzles come to mind. Especially when some of the leads do not lead in the right direction, in which case the problems of mazes also come to mind. Some of them intend deliberately to deceive, which does not seem fair. Not only to us, you understand. To the books, too.

Medieval Ownership and Monastic Use for Reading Aloud, Preaching Probably Included

In combination, evidence upon the pages of the manuscript itself attests to its earlier history before it surfaced in print in sales catalogues. Of course, following the mid-20th-century dismemberment of the manuscript, the recognition of this evidence has had to proceed piecemeal, with the introduction, apparently inevitably, of inconsistencies in or between some interpretations. However, some elements have become clear, or at least clearer.

A series of inscriptions — partly erased and partly recoverable under Ultra-Violet lighting — spaced across some lower margins (at the openings of the Books of Nehum, Ohadiah, Genesis, and Psalms) reveal that the Bible had been owned by a Mirmellus Arnandi, lawyer and judge (Ego mermelus arnandi legum doctor et . . . Judex), who bequeathed it in 1450 to a house (‘convent’) of the Brothers of the Dominican Order, who dedicated their efforts to preaching. And so, some first steps in the voyages of the book are documented, although they leave some gaps in the history of its transmission.

1. Production of the manuscript, but where and when exactly? Not yet known. Circa 1325? The styles of the script, decoration, and illumination may narrow the probable range. Scholars are working on it. Northern France? Flanders? Amiens? Elsewhere? Etc.

2. Acquired before 1450 by Mirmellus Arnandi (his dates and location are unknown).

3. Bequeathed by him in 1450 to an unnamed house of Dominicans, with many signs of use for readings in refectory and perhaps elsewhere.

Perhaps some entries (besides Arnandi’s in the first person) might become identifiable as the work of specific hands and/or specific centers. Some of them may represent traces of the history of the manuscript in the century or more between its production and its transfer from Arnandi to the Dominicans.

In a Word, Gorgeous, and a Layabout At That

This Bible, monumental in scale and glittering in its decoration with gold and other colorful pigments, was manifestly used, at least for a time, for reading in the monastic refectory, or dining area, as shown by the the direction in refectorio’ (‘in the refectory’) at the opening of the Book of Leviticus. As noted by several scholars for the different leaves, the forms of punctuation within the passages and the system of alphabetic notations entered in the margins to mark various passages for readings likewise demonstrate use in the Church or refectory. The Leviticus direction specifies which location, at least for that portion. The many other marginal insertions and corrections demonstrate efforts to improve or perfect the texts. There are many signs of use, which attest to a Bible consulted on multiple occasions.

The copious glossary giving the ‘Interpretation of Hebrew [and other] Proper Names’ which occur within the text of the Bible manifests the aim to supply this copy with an appropriate study aid. That the glossary is partly alphabetized, according to its AB-Groups, allows for some convenience in the finding process. That is, it is arranged by the letters A, B, C, and so on (in ‘A-Order’), and moreover partly alphabetized within those letter-groups (say up to the first two or three letters in the name), improving on a simple A-Order which lumps any words with the same initial letter into one batch, but not yet reaching the standard of a fully alphabetized ABC-Order, familiar now to us in full dictionaries or encyclopedias. Like the Bible itself, the glossary was large in scale and lengthy in scope.

Modern Travels: Round About and Back Again

The passage of the Bible manuscript through a series of sales rooms in the 20th century records its transfer from one collection to another and from one country to another until it reached the prying hands of Otto Ege. Then, with massive dismemberment, the dispersal of its leaves or groups of leaves accelerated the processes of sales and transfer, in bits and pieces, including further dismemberment and dispersal of some of those groups.

For example, the 16 lots of Ege manuscripts and fragments in the Sotheby’s sale of Western Manuscripts and Miniatures on 11 December 1984 included the partial ‘residue’ of 210 leaves from this book (lot 39). The subsequent fragmentation of that portion resulted in turn in its distribution in batches variously of 1, 2, or more leaves. In a notable ‘rescue operation’, 102 (maybe?) of those leaves were purchased by the Schøyen Collection, where they remain together as its MS 223. [My query has gone unanswered.] The other 108 leaves of the ‘Residue’ sold as one lot of 210 leaves in 1984 have found other destinations, only some of which can be identified, while some of those leaves, as well as other leaves from the book, continue to revolve through the sales rooms. A Not-So-Merry-Go-Round, given the destruction and elimination of traces.

It is hard to keep track of which is which, and which has gone where. At least the pre-dismemberment sales catalogues allow us to know that in its former state the manuscript contained 503 leaves. That was a big, thick book. Perfect for resting upon a lectern.

Once Upon a Time, It Was Whole

Before dismemberment, the manuscript passed through sales rooms several times and in different countries in the 20th century, as it moved from one collection to another, both before and after World War II.

- Sotheby’s (London), Catalogue of Valuable Printed Books, a Very Fine Illuminated Manuscript [this one!] . . . , 6–7 July 1931, lot 389: ‘The Property of a Gentleman Resident on the Continent’ [An Italian, perhaps, given the next catalogue’s description?]

- Parke-Bernet Galleries (New York), 29 November 1948, lot 326 (pages 118–121): the property of an ‘Italian Private Collector’. (Despite efforts, I have not yet seen this catalogue.) [Update: The 1948 catalogue, now seen, is incorporated into this account.]

And thus it reached Otto Ege and, so the story goes, his co-conspirator in the Book-Demolition Business, Philip C. Duschnes, who supposedly sold some parts of this book through the years. Or something.

Going the Rounds

Lists of the sales catalogues by various vendors continue to grow, as leaves from the dismembered manuscript continue to migrate, and as information about the materials continues to accumulate. They are a useful, indeed essential, resource for knowledge about the manuscript, but keeping track of them has its own challenges. Such lists are presented, for example, online for Schøyen MS 223 and in print for Gwara, Handlist 14 (pages 121–122), albeit with some differences between various of the lists, some omissions, and a few mistakes.

Or Not, at Least Not This One

For the record, it is worth reporting that the sales catalogues wrongly cited in Gwara, Handlist, 14, Reference numbers 2 and 4, for both

1) Librarie Ancienne Ulrico Hoepli, Bibliothèque Joseph Martini. Livres rares et precieux d’autres provenances, Première Parte, 21 May 1935 (Zurich), lot 214; and

2) Giraud–Badin, Bibliothèque de M. Pierre Guérin . . . , Première Partie (Paris), 13 December 1938, lot 16

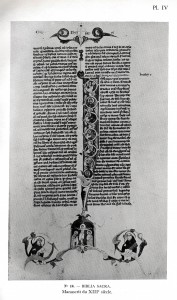

do not represent this Bible, but another one, made in Italy, with 506 leaves and a different Genesis opening (as illustrated in both those catalogues). The title page and plate for the Guérin case are shown here from a copy in a private collection, reproduced here by permission.

So we must look elsewhere for information about where the Bible went between the Sotheby’s Sale in 1931 and its re-appearance on the market in New York after the war. Not to mention where all its parts went afterward.

Not This One Either

Speaking of which. Same pertains to the group of sales catalogues wrongly cited in Gwara, Handlist, 14, Reference number 5. It took much work, and some wasted funds, to ascertain those wrong leads. And so, also from any lists of the sales catalogues claimed to be pertinent to this Bible must be removed the 4 cited cases of Philip C. Duschnes:

- Catalogue 169 (1964), numbers 12–18 (pages 4, 7–8, and 18–22 with 6 plates, without a plate for number 14)

- Catalogue 174 (1966), numbers 8–11 (pages 8–11 with 3 plates, repeating them from the previous catalogue, and without a plate for number 10)

- Catalogue 179 (1966), numbers 18–19 (pages 12–13 with 1 plate, repeating it from both previous catalogues, and without a plate for number 19)

- Catalogue 187 (?1968), numbers 152–153 (pages 26–27 with 2 new plates, 1 for each leaf).

They all concern various leaves sold separately from a single 46-line Bible different from this book. Five of those leaves re-surfaced as Sotheby’s, Western Manuscripts and Miniatures (21 June 1994), lots 17–18, correctly identified as leaves separated from ‘an extremely fine manuscript Bible, illuminated in Paris c. 1320–40 in the court style of Jean Pucelle and his followers, which was sold in these rooms, 6 July 1964, lot 239′ as a whole volume which had belonged to Saint Albans Abbey in southern England. Obviously its dismemberment postdated the lifetime of Otto Ege.

[After this post appeared, the attribution for another leaf for sale by Scott Gwara from that Bible incorporates this revised information.]

The bibliographic requirement calls into question the supposition that Duschnes would have been involved with Ege in the procurement, dismemberment, and/or distribution long-term specifically of Ege Manuscript 14 and its remnants. His hand in other dismemberments of Ege Manuscripts can be established, but not, apparently, in this case.

Lessons to Learn

A lesson here is that, like many other spheres of research, the field of dispersed manuscripts requires checking and rechecking the sources. In their case, the sources can include a bewildering, elusive, shifting, and sometimes misreported quantity of catalogue descriptions, sometimes with illustrations. A bonus of the illustrations, where provided, is that, to educated eyes, they can confirm, rule out, or leave hanging the potential identification of the materials, or part of them, with the right manuscript.

By the way, if you remain sceptical, and think (not unreasonably) that the different reports of ‘503’ or ‘506’ leaves in total for the Bible still intact could represent mistakes in counting or variants in reporting at different sales, say including endleaves or not, let me point your attention to the 2 different pages with initials for Genesis 1:1 as illustrated in the Sotheby’s Catalogue of 1931 on the one hand and in both the Martini and Guérin catalogues on the other hand. They are so not the same book!

Tricky. And I haven’t yet managed to find access to all of the catalogues I know about. Some of my research inquiries remain unanswered. [As listed below.] For now, let us be glad for what we can find so far.

In the Beginning

Before we turn to the issues of the individual leaf, it is worth taking into account the sellers’ reports about the book while it was still mostly intact — albeit, as they noted, with some damage to the binding and a few leaves at both front and back, as well as the loss already of miniatures cut out from 5 leaves. The absence of folio- or page-numbers on the leaves themselves continues to impose some uncertainties for the reconstruction of their former sequence, not least because the order of the Books of the Bible in manuscripts of the 13th-century (and other periods) could exhibit variation.

1. The View from London in 1931

Therefore the citation in the Sotheby’s sale catalogue of 1931 (on its page 47) of 15 specific folio numbers — and its care to indicate their verso (with a ‘B’) or recto (without further distinction) — in signalling some significant illustrations, initials, and marginal ‘grotesques and drolleries’ deserves consideration as valuable evidence. Not as much as we might wish, but it is something.

For example, out of the total of ‘Seventy-eight large miniatures’ — their survivors demonstrate that the term here means, at least sometimes (where I have been able to discover), historiated initials rather than separate scenes as such — the catalogue lists ten ‘among the more remarkable’ and cites their folio numbers (highlighted here in red), although, it seems clear, those numbers did not appear on the leaves themselves. Useful to keep track of them; highlighting helps. Those initials were to be found respectively on folios 46 (Book of Numbers), 155 (II Chronicles), 191 (Judith), 220 (Psalm 54), 253 (Ecclesiasticus), 266B (Isaiah), 308B (Ezekiel), 345B (Nahum), 440 (Acts of the Apostles), and 457 (Apocalypse).

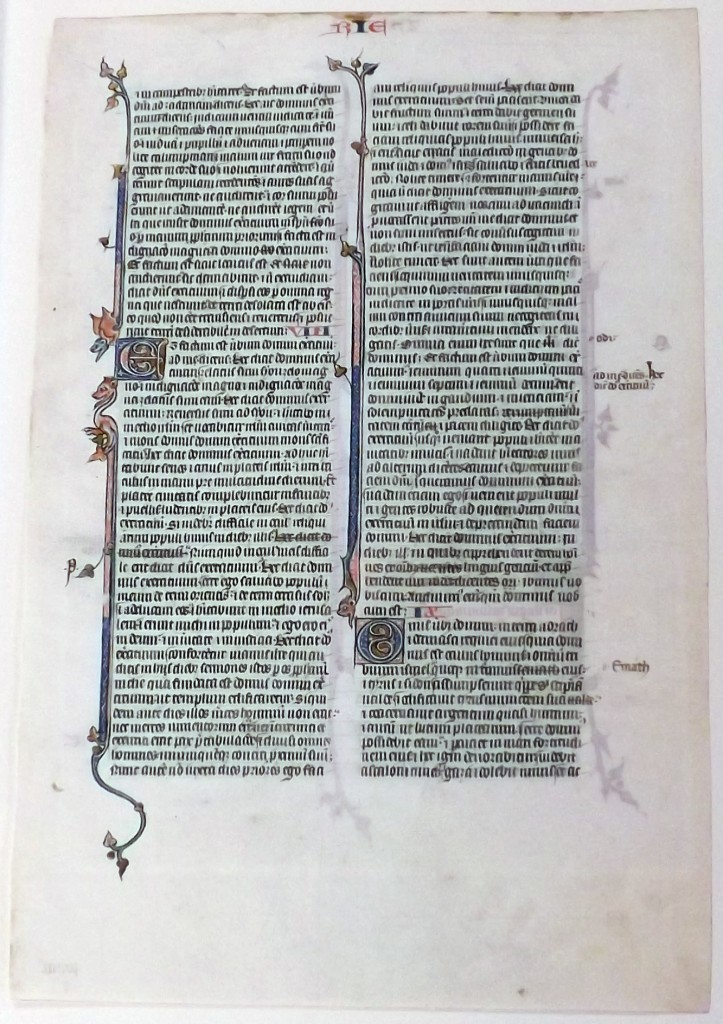

The Top Ten were (was?) selected for mention stood as next-in-line to the ‘magnificent initial I . . . running the length of the page representing the six day[s] of Creation, the Almighty, and the Crucifixion’ for Genesis 1:1, on a folio number not cited (but it cannot have been number 1 because of the surviving parts of the Prologues which stood before it). This first page of Genesis is illustrated in the fold-out plate for the catalogue, along with another plate facing the lot description, with 3 details identifiable from the description as showing part of folio 253ra (focusing on the initial for Ecclesiasticus 1:1) and two parts of folio 388B (in Mark Chapter 10).

As an aside, it is tempting to think that the choice of plates may have included some irony, not only the irony that may come with hindsight that so few elements of the Bible received a record while there was still chance. (Who knew what would come, including a World War?) I mean, it cannot be lost on everyone, given the context of the sale, that the detail illustrated from the top of folio formerly *388vb (that is, using ‘b’ for column b on the verso), with a pair of fanciful gesticulating hybrid creatures, part human, part dragon, reproduces the passage about rich men versus camels in Mark 10:24.

And so, here, in referring to any surviving leaves which correspond to those specific recorded numbers, or can safely be identified as immediately adjacent to those known numbers, I cite them with asterisks, as with folio *345v for the page with the miniature of ‘Nahum and the destruction of Nineveh’. The record of folio numbers supplied by Sotheby’s cataloguer in 1931 in connection with the mention of some selected significant features of illustration and decoration permits us to know that the Interpretation of Hebrew Names came at the end of the volume, following the Bible texts, and that it opened on folio *465r, with one of the two outstanding ‘large and very fine’ instances ‘among the illuminated initials’. As such, its initial was comparable in stature to that for the Prologue to I Kings on Folio *93v. They were surpassed only, it might appear, by the monumental full-page initial for Genesis 1:1 — showcased in the fold-out plate for lot 389 of the two-day 1931 Sale which culminated in this ‘Very Fine Illuminated Manuscript’.

Here is a case where, shall we say, the Last could indeed be a First. And so it was, represented in Sotheby’s pages and premises in New Bond Street, after being delivered thence by ‘a Gentleman Resident on the Continent’, that the manuscript entered the Age of Print. A precarious journey, at best, once it got there.

2. The View from New York in 1948: The Last Hurrah

[This section is an Update, with thanks to Sotheby’s Inc. for access to the catalogue entry and permission to reproduce its image.]

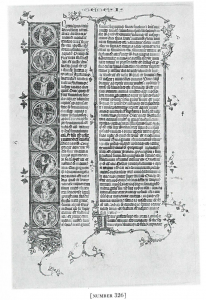

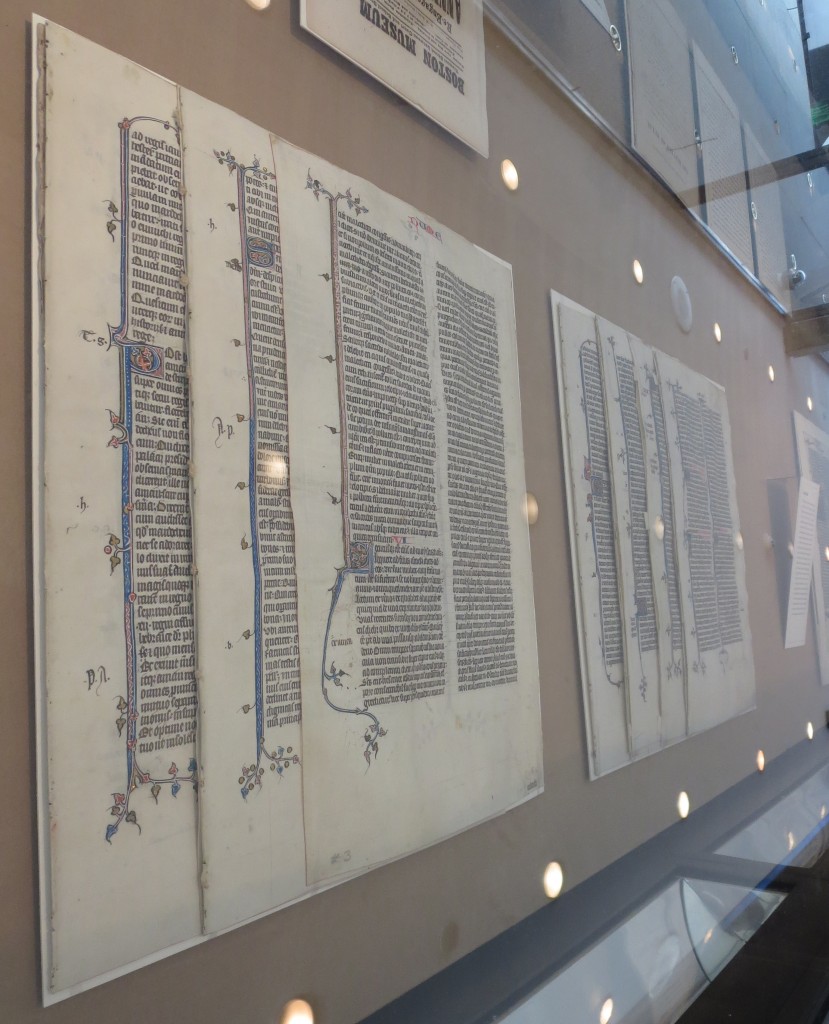

Opening page for Genesis in ‘Otto Ege Manuscript 14’. Photograph Courtesy of Sotheby’s, Inc. © 29 November 1948, lot 326, plate on page 118. Reproduced by permission

The Parke-Bernet Galleries sale catalogue of 29–30 November 1948, lot 326 (on its pages 118–121) cites no folio numbers for the manuscript, but offers several additional testimonies, which benefit from cross-comparison with other evidence. The total of elements deemed worthy of mention differs somewhat from the report of 1931, but probably not because the book itself had changed much.

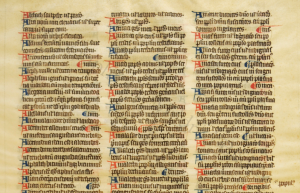

It is declared to possess ‘EIGHTY-SIX HISTORIATED INITIALS OR MINIATURES PAINTED IN BURNISHED GOLD AND COLORS ON DIAPER-PATTERNED GROUNDS’ [as against 78 in the record of 1931, according to whatever counting of initials, miniatures, and/or other], and to have ‘numerous smaller exquisitely executed initial letters IN BURNISHED GOLD AND COLORS, ornamental marginal decorations throughout, with foliated terminals, grotesques and drolleries’. The 2 plates illustrating the item (on catalogue pages 119 and 121) exhibit the opening page of Genesis (a recto) and the page with the historiated initial for Psalm 109 (apparently a verso).

Proof that no more spoliations had occurred between the sale of 1931 and that of 1948 is demonstrated by the declaration that ‘Five leaves are defective owing to the removal of the miniatures’. That means a robbery of those portions had occurred before 1931 and the hand-over of the book to sale then by a ‘Gentleman resident on the Continent’.

Five missing ‘miniatures’. Their five holes were evidently clear enough at the times of sighting. One of the missing miniatures could be the one that was used to replace the one despoiled from another leaf, as reported by Judith H. Oliver, Manuscripts Sacred and Secular (1985), no. 36 (on a leaf ending Kings and moving to I Chronicles), although without any plate to demonstrate or description to indicate its subject: ‘Large rectangular cut-out patch lower quarter of one column to cover theft of illuminated initial for I Chronicles. Patch taken from another illuminated page of the same manuscript’. That leaf belongs to Boston University (STH MS. Leaf 38), which means that one of the 5 listed (but not identified) despoiled miniatures might still survive on it.

However, the dismal possibility remains that the replacement miniature on that leaf could have come from the concerted despoliation which followed the 1948, sale rather than the earlier attested but unspecified losses. It remains to be seen what that patch shows and what its method of application might tell. [Note to Self: Have a look at that leaf, if or when possible.]

Psalms 108:13 to 112:4 on a verso. Photograph Courtesy of Sotheby’s, Inc. © 29 November 1948, lot 326, plate on page 119. Reproduced by permission

Useful for our time-travel back to the original manuscript, guided by this New York sellers’ description, is also the list of ‘miniatures’ selected for mention. ‘Among those that can more readily be identified’ are these, set out here in the cataloguer’s order, which order does not correspond with the Biblical order (not a complaint, just a statement):

- ‘Moses (“depicted with horns”) and the Almighty’

= Exodus something, say 6:2, 12.1, 19:9, 33:11, 33:17 - ‘Moses holding the Ten Commandments’

= Exodus 20, which perhaps delimits the former citation to the earlier occasions in Exodus, not the latter - ‘Judith and Holofernes’ rendered ‘in a rather gory representation of this subject’

= Judith 1:1 on folio 191r - ‘King David Playing’

= say I Samuel? Psalms 1:1? Playing a harp, presumably? - ‘the Last Judgment’

Rare cases in late-medieval Bibles, variously as historiated initial or miniature accompanying the text, place this scene preceding either Psalm 50:3 in the bilingual Greek–Latin Hamilton Psalter probably from Cyprus, or both the Prologue and Chapter-List for the Book of Zephaniah in the Bible of Heisterbach of circa 1250–1260 - ‘a king striking church bells with two hammers’ for Psalms

= Psalms 1:1?

Or some other Psalm?

For example Psalm 80, as in at least one more late-medieval Bible (the Bible of Heisterbach of circa 1240) - ‘the Holy Trinity’

This must be the initial for Psalms 109:1, reproduced in the plate on page 121 for lot 326, and reproduced here with permission. Two cross-nimbed and bearded men gesture toward the descending cross-nimbed dove. Trinity as ever was. - ‘Saint Barbara holding her emblem of martyrdom’

Given that this saint, if she is the Barbara of Nicomedia, apparently dates from the 3rd century CE, and so cannot be a canonical Biblical figure, her emblems customarily of chains plus tower could indicate that this cataloger’s identification in fact intends the image of the crowned and enthroned Ecclesia with her edifice in the opening initial for Ecclesiastes, as reproduced in the Sotheby’s catalogue of 1931 ( = folio 258r). That’s my vote. - ‘the martyrdom of Saint Stephen’

= Acts 7:54–60 - ‘a curious representation of a reclining figure above whom are the symbols of the evangelists’

= presumably Ezekiel 1, say, folio 308B, unless the initial with that vision is another one in the same prophet’s Book or that Chapter - ‘Nahum and the destruction of Nineveh’

= folio 345B - ‘Abraham about to slay Isaac’

= Genesis 22:2–8

Important about this set of descriptions is the certainty, from the different attributions, that the cataloguer did not have access to the Sotheby’s Catalogue of 1931. He/She started afresh. That conclusion allows us to credit the other components of the catalogue description to a greater extent than could be available for a simple copy. Interesting.

Most of a whole paragraph in the listing is devoted to a celebration of ‘the repeated deployment of grotesques as part of many of the illuminations’. It focuses upon ‘one very outstanding page’ which ‘does not display historiated initials or miniatures, but original marginal decorations of such character that it is as important as any leaf showing one or more miniatures’. The description makes it clear that this page is folio 388B with Matthew 10, as illustrated in 2 details in the 1931 catalogue, including the elements which the 1948 catalogue convincingly (details included) identifies as the ‘wizard’ and the ‘half-musician, half-grotesque’, that is, at the top of the page. But the description also offers a record, in addition to those plates, of the ‘grotesque’ figure at the top right, namely ‘a knight in armor with a shield’ and a body that ‘terminates in a vine leaf’. If that leaf survives, those elements would be recognizable.

Useful too is the report that ‘the first three leaves (Prologue) and a few leaves of the Table at the end are stained’. Already before seeing this catalogue [in other words, this is an Update], I had been able to discern that the Prologues for this lectern Bible must have spanned 3 leaves (see my list below). Nice to have confirmation [ditto] from a source facing the original manuscript, its damaged traces included.

About that ‘Table’. Remember the Sotheby’s 1931 Catalogue and its mention of a some of its leaves damaged at the very end of the book? I used to wonder if the description might refer to something else than the Interpretation of Hebrew Names, but this catalogue of 1948 makes me reconsider. ‘Table’ in the catalogue of 1931′ might well concord with the ‘Table’ in the catalogue of 1948. [Does this mean that my assumption that the second cataloguer did not have access to the report of the first? Yes.

Do I know the answer? No. Is it useful to keep these complexities in mind? Of course. At best, you could leave it to me, and I’ll report when the results becomes clearer. OK? Or, would you help? Nice!

Also, could that term of ‘Tables’ concord with an item in a contents’ list in the original manuscript? Tempting. Could be. Is such a term generally applicable to the Interpretation of Hebrew Names, of whichever persuasion? Not sure yet. So, until further evidence emerges, let’s go for the interpretation of that text as the last text of the Bible, no others involved.

Remember, we are looking for some damaged leaves, let’s say by moisture, at the end of this formerly magnificent, but neglected Bible, which came to be dumped onto the market after the Second World War in the United States by way of an Italian. A shame if they are lost!

Remnants Recognized and ‘Reassembled’

Besides the 40+ individual leaves which settled into the individual sets of Otto Ege’s Portfolio as its Leaf Number 14, many more leaves have been distributed by other means. Their travels can be discerned partly in the sales catalogues through which these single ‘Rogue Leaves’ or larger groups of ‘Residuals reached their current homes. Some are viewable online. The principal remnants of the ‘Residue’ of 210 leaves sold to Maggs Bros Ltd. in 1984 and sold in sections reside in MS 223 of the Schøyen Collection of ‘Manuscripts from around the world spanning 5000 years of human culture & civilisation’. Only part of one page from that large residue is visible online at present.

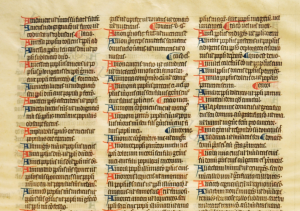

Most of the recognized leaves contain parts of the Old or New Testaments, including the Prologues prepared for them by Jerome (circa 347 – 420 CE), translator and editor of the Vulgate Version of the Latin Bible. These Biblical parts of the manuscript present their texts in double columns of 50 lines, with a written area of circa 403 × 185 mm. They have polychrome running titles in the upper or outer margins, chapter numbers according to the numbering which became mostly standard for the Bible by the 13th century (and which remains in use), and generous decoration.

The decorated initials for the openings of Books stand at various heights inset within the columns and have band-like extensions forming borders which span the heights of the columns and reach into the upper and lower margins with foliate and other terminals. Some of the initials for Books or their Chapters include illustrations of individual figures or scenes, functioning as historiated initials. Perhaps, as suggested in some published descriptions of the book or its bulk, some framed illustrations on their own function as ‘miniatures’, that is not part of initials but stand-alone — but I have not yet discovered any such elements, only historiated initials combining letter and scene (plus decoration).

The historiated initials have been compared — for example by Sandra Hindman in Bruce P. Ferrini’s sale Catalogue One (1987), page 44 (numbers 25–27) — to the work of the artist of the early 14th-century copy of the Lancelot cycle in French preserved in Bodleian Library, MS Rawlinson Q. b. 6 (Summary Catalogue, number 27855), now partly digitised. The colophon of that book reports its scribe’s name as Ernouls of Amiens. Such correspondences in style and approach may guide the assessment of the probable place and date of origin of this Bible. Perhaps, in time, the identity of some of the different scribes, correctors, artists, and annotators might become recognized, so as to locate the centers involved in its origin and transmission.

Adelaide Bennett has suggested to me that it is worth comparing the style of the manuscript also to Princeton University, Garrett MS 29, a large-format 2-volume Bible with Prologues and the Interpretations of Hebrew Names. This 41–42-line Bible was made in the last quarter of the 14th century probably in Southern France. A description appears in Don C. Skemer, Medieval & Renaissance Manuscripts in the Princeton University Library (2013), volume 1, pages 17–22, augmented by a checklist of images and descriptions. Its version of the ‘Interpretations of Hebrew Names’ begins with Aaz apprehendens uel apprehencio and ends with Zuzim consiliantes eos uel consiliatores eorum (Volume II, folios 354v–422r in double columns). In the process of examining that manuscript directly, there emerge some features which illuminate characteristics of our New Leaf.

Before moving onto a preliminary and partial reconstruction of the manuscript, it bears remembering that a central focus for our investigation is the Interpretation of Hebrew Names. As represented by a few remnants of the manuscript, including the New Leaf, it is apparently the version beginning Aaz apprehendens (‘[The name] Aaz means “seizing” ‘), or a variant (one of several) of that version, although its opening does not(?) survive.

Remember, this copy presents their text in triple columns of 50 lines, with a written area of circa 289 × 194 mm. The inset 1-line opening letters of the lemmata, citing the names or terms (in transliterated Latin for the Hebrew, Aramaic, or Greek) to be defined or explained, are written alternately in red and blue pigment. The inset 1-line C-shaped paraph-like signs, indicating the lines of the explanations which run over into the next line (or two) or ahead into an available space in the preceding line (or two), are written alternately in blue or red, while a curved line in ink helpfully directs the reader either downward or upward to the appropriate run-over or run-ahead. Legibility is often key, here and elsewhere in the book.

You may think that these features are boring and unimportant. You could be right, but I think that they have value as part of the whole, and deserve attention, in addition to the rest. Speaking of which, it’s Now On With the Show.

Some Known Remnants

Here follows a partial list of the Remnants, based on some materials to hand. The identifications of the textual contents offer corrections for the published reports of a few leaves. Please note that this list is not complete, even for the records that I know about, let alone the ones yet to emerge into view. For example, some of the sales catalogues remain elusive, but they may surface.

In this list, the order of the scattered leaves from the Books of the Bible mostly follows the standard Vulgate edition, but their order in the manuscript seems to have differed somewhat. Where it differs, the actual order can be determined, at least in part, by the Known Folio Numbers (see above) and the text on some survivors which end one Book of the Bible and begin another. A case in point here is the leaf which begins Paul’s Epistle to the Hebrews, directly followed by the Acts of the Apostles.

I cite all the Known Numbers as locators in the series, even where the survival of those very leaves might remain uncertain. For emphasis, they are shown in *red, together with their asterisk. In the analysis following this list, any conjectured, rather than recorded, folio numbers are preceded by a question mark, also in the red (?*300). As I hope you might see, keeping track of these details has a purpose, sometimes (as here, hurray) with a payoff.

Vulgate Bible with Prologues and Interpretationes Hebraicorum Nominum

Several sellers or collections list groups of leaves which include, or might include, non-consecutive leaves and/or leaves acquired at different times from different sources. Sometimes they cite the contents in some detail, sometimes not. Examples include some non-continuous leaves listed in a single lot number, gathered in a single collection, or grouped in a large batch in a single collection. As here:

- 102 Residual Leaves = Gwara Handlist 14.7. Oslo and London, The Schøyen Collection, MS 223.

Its full contents are not known to me. The specimen image on the collection’s website shows a detail of the page with

Paul’s Epistle to Philemon and the beginning of his Epistle to Hebrews - 3 non-continuous Rogue Leaves = Gwara Handlist 14.9. Metropolitan Museum of Art = William D. Wixon et al., Mirror of the Medieval World (1999), pages 118–119 (number 141), Leaves ‘1’, ‘2’, and ‘3’, with portions of Ezdra > Nehemiah [?], of Joshua, and of Ephesians 1:1 – 2

Here I list the contents in their Biblical places, insofar as they are revealed. To a surprising extent, a number of my research inquiries await responses. Some leaves I know only through the sales catalogues, not their destinations. It’s a start.

Old Testament with Prologues

Psalms 108:13 to 112:4 on a verso. Photograph Courtesy of Sotheby’s, Inc. © 29 November, lot 326, plate on page 119. Reproduced by permission.

Rogue Leaf (1 of 2 from the Esther Rosenbaum Collection). Sotheby’s, Catalogue of Single Leaves and Miniatures from Western Illuminated Manuscripts, 25 April 1983, lot 83(a), without plate

described in the catalogue as the ‘Opening leaf of the Bible, with the [First] Prologue of St. Jerome‘ beginning Frater Ambrosius, and extending to labiis personaret, ‘which shows the secundo folio to have begun’ with ignorabat eum

[1 leaf in this Prologue, from ignorabat eum in Chapter ‘VI’ to et regna in Chapter ‘VII’, remains unaccounted for.]

Rogue Leaf = Gwara Handlist 14.8. Randolph College

Part of Jerome’s 2 Prologues to the Bible (that is, 2 of his own Epistles):

Part of Frater Ambrosius, from within Chapter ‘VII’ (omnia subvertentem) to the end, all of Jerome’s [Second] Prologue Desiderii mei in full, and Opening Title for the Book of Genesis

[Opening of Genesis 1:1 on a recto

(Reproduced as the fold-out plate for the Sotheby’s catalogue of 6–7 July 1931, lot 389; and as the first of two plates for the Parke-Bernet catalogue of 29 November 1948, lot 326 (plate on page 119), while the manuscript remained whole. This plate from the Parke-Bernet catalogue is also reproduced in Gwara, Otto Ege’s Manuscripts, figure 79. I do not know if the leaf survives.)

[Update: Yes, it is now in the Otto Ege Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. A report about this collection is in preparation for the Research Group Symposium on ‘Words & Deeds’ in March 2016.]

Rogue Leaf. Maggs Bros, Papyrus to Paper. Catalogue 1059 (1985), number 49, ‘a leaf with four dragons’ (with plate on page 28 of top half of verso)

Genesis 32:29 ([interroga-/]uit to 34:6 and beyond in the lower half of that verso

Rogue Leaf. Maggs Bros, Papyrus to Paper. Catalogue 1059 (1985), number 42 (no plate)

Genesis ‘end ch. 42, ch. 43 & most of ch. 44’ with ‘drawing of a rabbit with calligraphic flourishes’ in the upper margin of the recto

Rogue Leaf (2 of 2 from the Esther Rosenbaum Collection). Sotheby’s, Catalogue of Single Leaves and Miniatures from Western Illuminated Manuscripts, 25 April 1983, lot 83(b), with plate from the upper part of one side (unspecified)

including the Prologue to Exodus and the opening of Exodus 1 with historiated initial

Rogue Leaf (3 of 3) sold by Bruce P. Ferreni, Catalogue One: Important Western Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts & Illuminated Leaves (1987), number 27 (page 44), without plate

Exodus 9 – 11

[Numbers initial = *46r]

Set 27. University of South Carolina, reproduced also here

Numbers 8.10 (suas) – 11.13 (ut co-[/medamus])

Rogue Leaf (1 of 2). Sotheby’s, Western Manuscripts and Miniatures (21 June 1994), lot 10(a.1), without plate

Numbers 19–21

[Joshua initial = *73v]

Rogue Leaf (2 of 3) = Gwara Handlist 14.9. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1994.539 = Wixom et al. (1999), no. 141, Leaf ‘3’ with plate on page 119, column b

Joshua 8:32 ([la-]/pides] – 10:1 (sicut enim fecerat) on verso

[Prologue initial for I Kings = *93r]

Rogue Leaf. RMGYMss Bible Leaf Ref 180

III Kings 11:20 (eum) – 13:15 (end)

Rogue Leaf = Gwara, Handlist 14.1. Boston University = Judith H. Oliver, Manuscripts Sacred and Secular (1985), number 36 [but no plate]

End of Kings, Prologue to I Chronicles, and beginning of I Chronicles,

with a ‘patch taken from another illuminated page of the same manuscript’ covering the cut-out from the ‘theft of initial for I Chronicles’.

[One wonders which other page yielded its riches to patch up this leaf.]

2 Rogue Leaves = Gwara Handlist 14.10. Hollins University

These leaves include a page with the End of I Chronicles, Prologue for II Chronicles, and beginning of II Chronicles

[= *155r]

(reproduced in Gwara, Otto Ege’s Manuscripts, figure 51)

Rogue Leaf. Stanford University[No longer available at “http://artsinstitute.stanford.edu/sites/scriptingthesacred/gallery/case-bible/” via Stanford Arts Institute], purchased from Bernard Quaritch, Medieval Manuscripts. Catalogue 1396 (2010), number 10, with color plate of recto

II Chronicles 4:12 ([episty-/]lia) – 6:10 (super thronum Israhel)

with quire number xiiii on bottom recto [= say folio ?*157, as reckoned below]

Set 13. University of Minnesota

Prayer of Manassas Chapter 15 (quoniam), Prologue to I Ezra, I Ezra 1:1 – 2:62 (eiecti sunt)

Rogue Leaf (1 of 3) = Gwara Handlist 14.9. Metropolitan Museum of Art = Wixom et al. (1999), no. 141, Leaf ‘1’ with plate on page 118, column a of one side of the leaf (unspecified)

Ezdre I > Ne[he]miae as indicated in the running titles

I Ezra 10:13 (in sermone) – 44 (end), beginning of II Ezra [= Ezra 11:1–10 (manu tua)] on one side of the leaf

Rogue Leaf. Maggs Bros, European Bulletin 13 (1986), number 52 (with plate of lower half of recto)

Nehemiah 5:18 – 7:3 (porte clausae) on that portion of the page

[Judith initial = *191r]

Set 30. Denison University

Judith 16:31, Jerome’s Prologue to Esther, and Esther 1:1–2:19

Verso of Rogue Leaf with part of I Maccabees from Ege Manuscript 14 at Kent State University. Reproduced by permission

Recto of Rogue Leaf with part of I Maccabees from Ege Manuscript 14 at Kent State University. Reproduced by permission

Rogue Leaf. formerly Boston, Endowment for Biblical Research = Judith H. Oliver, Manuscripts Sacred and Secular (1985), number 35, without plate

Job 31:1 – 33:20

[Psalms 54 initial = *220r]

Psalms 109 initial. Parke-Bernet Galleries, Sale Catalogue of 29 November 1948, lot 326, plate on page 121 (apparently a verso)

Psalms 108:13 (generatione) – 112:4 (do-[/mine super caelos])

[Maybe here in the original sequence?]

Rogue Leaf. Christie’s, Illuminated Manuscripts, Continental and English Literature . . . , Sale Catalogue of 16 December 1991, lot 2, plate on page 14 with detail of initial (on a verso?)

Book of Wisdom initial 1:1 (full span of leaf unreported)

[Ecclesiasticus initial = *253r, reproduced in the Sotheby’s 1931 Catalogue, as reported above]

Set 5. Ohio University

Ecclesiasticus 39:25 – 42:26

[Isaiah initial = *266v]

Rogue Leaf (2 of 3) sold by Bruce P. Ferreni, Bruce P. Ferreni, Catalogue One: Important Western Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts & Illuminated Leaves (1987), number 26 (page 44), without plate

Isaiah 50 – 54; full span unreported

Rogue Leaf for sale via Charles Edwin Puckett

Isaiah 54:10 (commovebuntur) – 59:3 on recto; verso unseen

Set 24. Lilly Library

Jeremiah 37:20 (Ieremias in uestibulo) – 40:15 (peribunt)

Set 2. Ohio State University

Jeremiah 7:27 – 10:11

Rogue Leaves. Bifolium with non-consecutive leaves at the Cleveland Museum of Art

Leaf 1, verso. End of Baruch 6, Prologue to Ezekiel, Ezekiel 1.1 – 13 (et quase aspec-[/tus]) on verso

[= *308v]

Leaf 2, recto. Ezekiel 8:? – 9:? (precise span unreported)

Set 35. Rochester Institute of Technology

Ezekiel 18:21 – 20:11 (recto). ‘A scan of the verso is not currently available.’

Set 37. Case Western Reserve

Ezekiel 27:30 (amare) – 30:20 (in un-[/decimo])

Set 32. University of Colorado at Boulder, recto and verso

Ezekiel 33:31 ([popu-/]ulus meus) – 35:3 (meam)

Set 4? [Or a Rogue Leaf?] Cleveland Museum of Art

Prologue to Jonah, Jonah 1.1 – 3.3 (et [/ surrexit]) on recto

Set 22. Cleveland Public Library

Micah 1:4 (sicut cera) – 6:2 (iudicum do-[mini])

Nahum initial = *345v

Rogue Leaf. Maggs Bros, Papyrus to Paper. Catalogue 1059 (1985), number 46 and plate on page 27 with detail of initial

‘The final chapter of the Book of Micah and the opening two chapters of the Book of Nahum’, plus Mirmelus’s inscription in the first person

Rogue Leaf (1 of 3) sold by Bruce P. Ferreni, Catalogue One: Important Western Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts & Illuminated Leaves (1987), number 25 (page 44), with plate of verso

Habakkuk 1 (span unreported) – 3, Prologue to Zephaniah, and Zephaniah 1:9 (super om-[/nem])

Set 15. Kent State University

Zachariah 7:7 (et in) – 11:10 (cum omnibus), reproduced here by permission

Rogue Leaf. Kent State University = Gwara, Handlist, Number 14.5

I Maccabees 12:29 (lumina ardentia) – 14:4 (et quesiuit), reproduced here by permission

New Testament with Prologues

Recto of Leaf 8 in Portfolio Set 9. From the Collection of The Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County. Reproduced by permission.

[Matthew 10 = folio 388B. The figural elements among the marginal decorations on this ‘one very outstanding page’ without ‘historiated initials of miniatures’, but with a rich repertoire of ‘grotesques’, are described in some detail in the Parke-Bernet catalogue of 29 November 1948, lot 326, page 120. Two details at top and bottom of the page are reproduced in the earlier Sotheby’s catalogue of 6–7 July 1931, lot 389, plate facing the description. I do not know if this leaf survives.]

Set 29. Lima Public Library

Matthew 27:46 (magna dicens) – 28:19, Prologue to Mark, and Mark 1:1–38 (eamus)

Rogue Leaf. Maggs Bros, Papyrus to Paper. Catalogue 1059 (1985), number 41 with plate on page 22 of top half of the verso

End of I Corinthians (from 15:56) and Opening of II Corinthians on the portion visible in the plate

[and not the opening of I Corinthians as stated in the catalogue]

Rogue Leaf (3 of 3). Gwara Handlist 14.9. Metropolitan Museum of Art = Wixom et al. (1999), no. 141, Leaf ‘II’ with plate on page 119, column a]

Epistle of Paul to the Ephesians, 1:1 – 2:10 (end) plus opening title for Chapter 3 on verso

Among the Residual Leaves = Gwara Handlist 14.7. Oslo and London, The Schøyen Collection, MS 223.

Its full contents are not known to me. The specimen image on the collection’s website shows part of the page with

Paul’s Epistle to Philemon and the beginning of his Epistle to Hebrews

[Might these 2 leaves have been consecutive? That depends upon what the rest of the specimen leaf contains.]

Set 6. University of Massachusetts at Amherst (both sides in black-and-white) and recto in color

Hebrews 1:13 (quando) – 6:20 (aeternum)

Recto of Leaf 8 in Portfolio Set 9. From the Collection of The Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County. Reproduced by permission.

Set 23. Kenyon College

Hebrews 10:20 (iniciauit) – 13:4 (conui-[/bium])

Acts initial = *440r

Rogue Leaf? Detroit Public Library [?]

Hebrews 13:4–25, Prologue to Acts, Acts 1:1–30

Set 25. University of Saskatchewan and here and here

Acts 4:1 – 5:11 on verso

Set 9. Cincinnati Public Library

Acts 13:37 (deus suscitauit) – 16:2 (Ychonio)

[Or do the Catholic Epistles follow Acts? If so, maybe here in the series?]

Rogue Leaf. Gwara Handlist 14.Ref 14. Sotheby’s 10 July 2012, lot 2(b) [Current location unknown to me]

Opening of the Catholic Epistle of James

Rogue Leaf. Maggs Bros, Papyrus to Paper. Catalogue 1059 (1985), number 44 with plates on pages 24 and 25 respectively of the verso and the top right-hand side of the recto

End of the Catholic Epistle I of James, all of his Epistles II and III, and the beginning of the Epistle of Jude (to verso 18)

[Apocalypse initial = *475r]

[Update: This leaf is now in the Otto Ege Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. A report about the collection, with illustrations, is in preparation for the Research Group Symposium on ‘Words & Deeds’ in March 2016.]

Set 17. Massey College, recto + verso

Apocalypse 2:27 (qui habet) – 6:9 (altare)

Interpretation of Hebrew Names

The recognized leaves from the Interpretatio Nominorum Hebraeorum for this Bible represent different parts of the partly alphabetized version beginning Aaz apprehendens (‘Aaz means “seizing” ‘), or one of its variants. So far I have discovered only 3 leaves, from the A-Group and the I-Group.

[Opening initial A = *465r]

Rogue Leaf: The New Leaf

Alcath . . . Ananias

Rogue Leaf: Enchiridion 21: Medieval Fragments for University Teaching & Research (2015), Item 2g

Asseremoth . . . Azer

Rogue Leaf (2 of 2). Sotheby’s, Western Manuscripts and Miniatures (21 June 1994), lot 10(a.2), without plate

with part of ‘the letter “I” ‘ (span unreported)

It is uncertain at present how many leaves intervened in the original sequence between the two in A. At least one leaf. It is also uncertain (to me) how the glossary ended, and if it was complete to Z.

All Bound Up

The record of 1931 (Sotheby’s lot 329) reveals that this text spanned an impressive part of the volume, from folio *465r onward, perhaps fully to as far as folio *503 (recto? verso?), in 38 leaves at most. And that, like ‘the first three leaves’ of the volume’, the last leaves (number unspecified) of the book were damaged: ‘a few leaves of the Table at end are somewhat stained’.

Presumably ‘the Tables’ means the Interpretationes Nominorum Hebraeorum? Unless, say, some contents list or other material? If so, that would affect the conjectured span for the glossary itself. Those stains perhaps represented the same sort of moisture damage visible on the Randolph College leaf with part of the Genesis Prologues and, presumably, on the first leaf of the Frater Ambrosius prologue.

Because, at the time of the 1931 sale, the volume still had its binding of ’17th Century calf over stout wooden boards’, with the ‘binding worn and upper cover loose’, we might conjecture that the damage to the front and back of the text block might have arisen from an unbound state, or from damage which affected those leaves as well as the covers of an earlier binding. Such a condition might have led to a 17th-century rebinding or rebacking. A pity that the binding on the volume may have been discarded, with all its evidentiary value of whatever kinds, in the 20th-century dismemberment of the monument. It could have told us much.

The Version of the Glossary

Various versions of the glossary of ‘Hebrew Names’ circulated in many Vulgate Bibles of the 13th century, large and small; they also appeared on their own. Jerome himself had created such a glossary — on a smaller scale and mostly in the order in which those names appear in the text — in connection with his long work on translating the Bible for his Vulgate Version. Over the centuries, many readers and scholars contributed to the processes of augmenting, rearranging, and further revising such glossaries, in a decidedly ‘fluid’ approach to the text.

The newer versions emerged in the many processes of expanding and restructuring the glossary of Biblical names (in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek) which Jerome produced in connection with his work of translating the Bible, and which mostly follows the order in which they appear in the course of the Bible text. Through the course of addition and revision, over the centuries, lengthy adaptations appeared in several forms, now mostly recognized in three main renditions, identified by their first entry: Adam, Aaron, and Aaz. Preserved in whole or in part in hundreds upon hundreds of witnesses, they mostly form addenda to Bible manuscripts.

The surviving copies represent many differences between them, including the numbers of their entries within a given version. No wonder that editions of those versions are partial and out-of-date. It would be appropriate, presumably, to focus upon a given manuscript version, or set of versions, for which some online viewings may reveal specifics.

To give a glimpse of their scale, but recognizing the many variations in the transmission, the versions of the glossary finally occur mainly in the Adam version with some 1,050 entries, the Aaron version with some 1,425 entries, and the Aaz version with some 5,250 entries (plus or minus). The latter was by far the most popular in the 13th and 14th centuries. Examples in Bibles in 3-column layout appear, for example, in Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 484, a pocket Bible, in a full span from Aaz–Zuzim on folios 631a–668rc; its A-Group spans folios 631a–637b, although without an exact correspondence in its relevant portion with the version on the New Leaf.

At present, knowing as yet of few other extant leaves from the glossary in Ege Manuscript 14, apart from the New Leaf, the University of South Carolina leaf, which formerly stood close together within the A-Group, and a leaf (location now unknown) from the I-Group, I cannot tell to which forms of opening and conclusion of the text this copy belonged. From those features it might be somewhat easier to identify the particular version. It might even, as with some witnesses to the various Aaz versions, have identified its author, or supposed author, in an opening or concluding title (or both).

The versions beginning with Aaz apprehendens (‘Aaz [means, or is to be interpreted as] ‘seizing’) moreover appear in several variants, with Aaz defined only as apprehendens, or provided as well with extended and alternate definitions providing the alternates ‘or apprehension’ or also ‘or apprehension, strength, or steadfast’. More than 900 witnesses to its text are known, both within bibles and on its own, in fluid approaches to its structure and contents. No wonder there is, as yet, no specific edition. Some witnesses are attributed in their manuscripts to the English Cardinal and Archbishop Stephen Langton (circa 1150 – 1228), to the Carolingian monk and author Remigius of Auxerre (circa 841 – 908), or to Pseudo-Bede, in a confusing conflation of textual traditions and aspirations.

For convenience, the variants of this version, or some of them, are listed by Friedrich Stegmüller, Repertorium Biblicum Medii aevi, I-XI (Madrid 1950-1980), volumes V and VIII.2, numbers 7708, 7709 and variants numbers 7192,1 (attributed to Remigius of Auxerre) and 1688,1 (attributed to Pseudo-Bede). These instances are indexed online via Repertorium Biblicum Medii Aevi.

Here is a list, attempting to show some clarity within the groupings, although the attributions exhibit many cross-overs.

- Aaz apprehendens = Stegmüller Number 7708 (Volume V, page 234), variously attributed

- Aaz apprehendens, vel apprehensio = Number 7708 (V, 234), mostly attributed to Langton

- ” ” = Number 1688,1 (VIII:2, 347), attributed to Pseudo-Bede

- Aaz interpretatur apprehendens vel apprehensio = Number 7192,1 (V, 65), attributed to Remigius of Auxerre

- Aaz apprehendens, vel apprehensio, fortitudo seu fortus = Number 7709, mostly attributed to Langton

If it seems difficult for us to sort out the different lines of transmission, imagine what may have faced the different scribes attempting to produce a reasonable, usable text for an ambitious Bible destined for reading aloud? That there are numerous mistakes in the transcription of the New Leaf — let alone its whole glossary — as manifested, for example, by the crossed-out passages here and there, could tell us of the frustration in efforts to make some sense of a complicated, perhaps jumbled, exemplar or set of exemplars. One knows the feeling.

The Nature, Purpose, and Function of the Glossary, Preaching Included

Detailed studies of these versions illuminate the processes of composition, variations, and dissemination of such approaches to studying the Bible in the 13th century, in particular the Aaz apprehendens version(s). For example:

- Giovanna Murano, ‘Chi ha scritto le Interpretationes Hebraicorum Nominum?’ (2010), pages 353–371, especially pages 362–371

- Eyal Poleg, ‘The Interpretations of Hebrew Names in Theory and Practice’ (2013), 217–236, especially pages 228–235

Murano’s survey usefully examines a number of the many witnesses to the text, both within bibles and on its own. Some witnesses in various formats are laid out in 3 columns, like Ege Manuscript 14. Poleg’s work explores the link between the Aaz glossary and the new form of preaching which arose in the practices of university teaching and the presentations of sermons by members of the mendicant orders — Dominicans included.

No wonder the recipients of Arnandi’s bequest made ample use of the book and marked it up with corrections, annotations, and indications for reading or preaching. Depending upon the dating of the many annotations to the Bible leaves, some of them could well belong to the period before Arnandi’s bequest, and thereby indicate a process of dedicated use before or during his acquisition. Maybe by others than Dominicans? Worth investigating.

The Price of Splendor (Or Not)

‘List of Hebrew Names’ in a ‘French Bible’ of ‘1300’, price ‘$2’, purchased in late summer 1953 at the Cleveland Museum of Art shop (Budny Handlist 8)

The original sales prices for some leaves from this manuscript were recorded in the handwritten notes, dated 1956, by Mrs. Otto Ege in a record of leaves sold at the museum gift shop at the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art (Gwara, Otto Ege’s Manuscripts, ‘Index of Prices’, page 347) as $15.00 and $35.00. Those differences presumably, as with Ege’s practices for some other dismembered manuscripts, reflected the greater and lesser degrees of decoration in their different leaves, so as to place the more elaborately embellished leaves at the higher level. The higher level would have fitted the historiated initials, or the ‘miniatures’ (if any), and left the mere (ha!) decoration to the lower level, with the relatively unembellished glossary to a level below mention. Shame.

A Bigger Price

Various of the Old and New Testament leaves contain decorated opening initials — some with historiated scenes — as well as border ornamentation. The totals for the many leaves (105? 210? Reports differ) preserved — whether gathered from a single source or from different sources of Lost and Foundlings into a single group — as MS 223 in the Schøyen Collection are impressive (as I highlight in red):

50 lines in a formal Gothic book script of medium grade, headings in red, running-titles and chapter numbers in blue and red, 230 illuminated initials, 222 bar borders with sprays ending in ivy leaf motifs in pink, blue and orange with white highlighting and gold decoration, 2 historiated initials, 5 11- to 12-line miniatures in pink on blue ground or blue on pink ground within a gold border.

If that total of 2 ‘historiated initials’ plus the 5 ‘miniatures’ (perhaps, say, combined in initials) comes to 7 from the total of 78 ‘large miniatures’ cited in the Sotheby’s Catalogue of 1931, then there remain very many to be accounted for. I have listed such as come into my span of acquaintance, while continuing to await responses to my research inquiries.

That the Metropolitan Museum of Art, among other institutions, has seen fit to welcome leaves from the dismembered Lectern Bible may demonstrate the museum-quality caliber of the materials, or at least some of them. It was once a very beautiful book. No wonder that some catalogue or handlist descriptions confuse it with one or more others exhibiting splendor and vivacity from the best centers in Paris or elsewhere. (Even if the very number of lines, which differ in themselves, should have warned those conflators away from such errors.)

Compared with these qualifications, the leaves with the glossary lists of ‘Hebrew Names’ having at best some elements in red and blue pigment would have seemed — to an assessment with a view to market ‘value’ and buyer-appeal — dreary, uninteresting, and boring. Humph. I think otherwise. They deserve their memorialization within the ensemble as we might be able to welcome it into a ‘Foundling Hospital’ of sorts, if only virtually and in our collective recollections. (I have already reported my wistful and constructive views about The ‘Foundling Hospital’ for Manuscript Fragments.)

On Recall

The owner of the New Leaf recalls purchasing the leaf at the gift shop of the Cleveland Museum of Art circa 1953. To start with, as I reported in an earlier blogpost, the recollected date was circa 1951. However, upon closer reflection (as of late August 2015), the date span is more closely recollected as part of a journey westward in the company of his mother for the commencement of the academic year of 1953–1954 at the University of Iowa. Therefore presumably the purchase took place in that August or so.

The Ege inscription in pencil at the bottom of the recto records the original price of ‘$2.—’ along with the identifier for the leaf as part of a ‘French Bible 1300 – List of Hebrew names’. Given the center of Ege’s activities in Cleveland and at its Museum of Art, this find-place at an early stage following Ege’s death and the ever-wider distribution of leaves and larger remnants from his collection seems prescient.

My report to you of these increasingly refined date-spans for the purchase of the leaf may encourage you to appreciate the value of asking your sources — written and in person — over and over, politely and persistently, about their memories. Some may surface and resurface, and some may resist or retreat for another day.

While we have to pursue our lives and work, it may be that we do not record or remember everything, especially where there is not an attendant team of archivists, et al., ready and waiting to tend to all those details. But is useful to have the opportunity to ask when we can, and with increasing focus. Happy I am that this process of persistence and perseverance allows for some firmer discoveries with value for the monuments (or remnants) themselves, on their own and in company.

The 1962 Census

The information supplied by the Ege inscription formed the basis for the first printed record of this leaf itself. With ‘descriptions furnished by the owner’ in Massachusetts, the Supplement to the Census of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts in the United States and Canada (1962), page 284, item 4, reports it thus:

List of Hebrew names, in Latin; possibly from a Bible.

Vel[lum], 1 f[olio], 22 x 16 cm. Signature-mark IIII in lower right corner. Written in France, ca. 1300. Initials in red and blue.

The medieval entry with the roman numeral iiij in ink at the lower right on the recto presumably cannot represent the mark for the opening of a signature or quire IV, given the location of the glossary (we know) at the end of a big book. Coming so far from the front in the set of *503 leaves, within a few leaves of the opening of the Hebrew Names on folio *465r, say within the late *460s, if not in the early *450s, that interpretation seems unlikely or impossible, although mistakes and variables in the counting of quires are known to happen.

Might it instead form a pecia mark to designate a unit of the copying itself? Or a pen-trial, to get the ink flowing? Or a cue for a quire number to be entered more emphatically on this recto? That is, if the leaf once began a quire. Hard to tell, given the trimmings of the margins on the detached leaves during their dismemberment.

The mark puzzled me until there came the chance to examine Garrett MS 29 (mentioned above), a Bible from Southern France with Prologues and an Aaz-apprehendens version of the Interpretation of Hebrew Names (similar but not identical), with an elaborately decorated initial for the opening of this glossary in Volume II, folio 355r; the complete glossary extends to folio 422va, in a span of 67 leaves. Several quires in the manuscript, comprising 8 leaves in 4 bifolia (quaternions), carry the traces of partly trimmed marks labelling the first four leaves plus the fifth to count their components in correct order. Although preserved only in fragments, because of the trimming for a rebinding, their series can be recognized as comprising a letter-mark or symbol (such as q, p, R, or an inverted triangle) followed by a set of narrow vertical strokes (from 1 to 4) on the rectos of the first 4 leaves of the quire, plus a simple cross (+) on the 5th leaf, that is, the first conjoint leaf in the assembled quire.

Might such a practice, or a variant, have governed the entry of the mark on the New Leaf? If so, could it mean that this leaf comprised the 4th leaf of a quire, and the 1st leaf of its former bifolium? Maybe the answers to such clues, now articulated, might become revealed as more evidence comes to light, and as more explorers learn what to look out for.

The Former Whole

The evidence of quire structures in other parts of the manuscript could help to answer some of these questions. For example, the recto of the leaf from II Chronicles at Stanford University carries a prominent quire-signature for the opening of Quire xiiij, written in the same stately bookhand as the main text and centered in the lower margin.

Combining the evidence takes us further. That quire XIV, beginning with II Chronicles 4:12, within a very few leaves after folio *155 (now at Hollins University) which carries the historiated initial for II Chronicles on its recto (as recorded for the Sale of 1931), permits the conjecture that the 156 or so leaves in Quires I–XIII up to that point in the volume would, if consistent, have contained 12 leaves apiece, say as 6 bifolios. Quire XIV may have begun on folio *?157. At 12 leaves per quire, the *503 leaves of the manuscript would have spanned some 42 quires, minus a leaf or so.

The glossary alone, whether complete or not (Who knows?), could have filled all or most of the 37 leaves from folio *435 to the end of the volume, that is, just over 3 quires if 6 leaves apiece, say with an endleaf or so to spare. Who can say. Too many questions remain open, but at least we could play this form of the Numbers Game. This form of play has carried us far in the quest bravely to reconstruct the book, at least in part. We await responses to more of the research inquiries to various institutions.

A Big Shame