Visit to the Collection of Steven Lomazow, M.D.

October 3, 2024 in Announcements, Event Registration, Manuscript Studies, Uncategorized, Visits to Collections

RGME Visit to the

Collection of

Dr. Steven M. Lomazow

of American Magazines

and Other Sources

Saturday 16 November 2024

In-person visit,

with hybrid component

for an online virtual visit (by Zoom)

“I can read you like a magazine”

— Taylor Swift, Blank Space (2014)

[Posted on 1 October 2024]

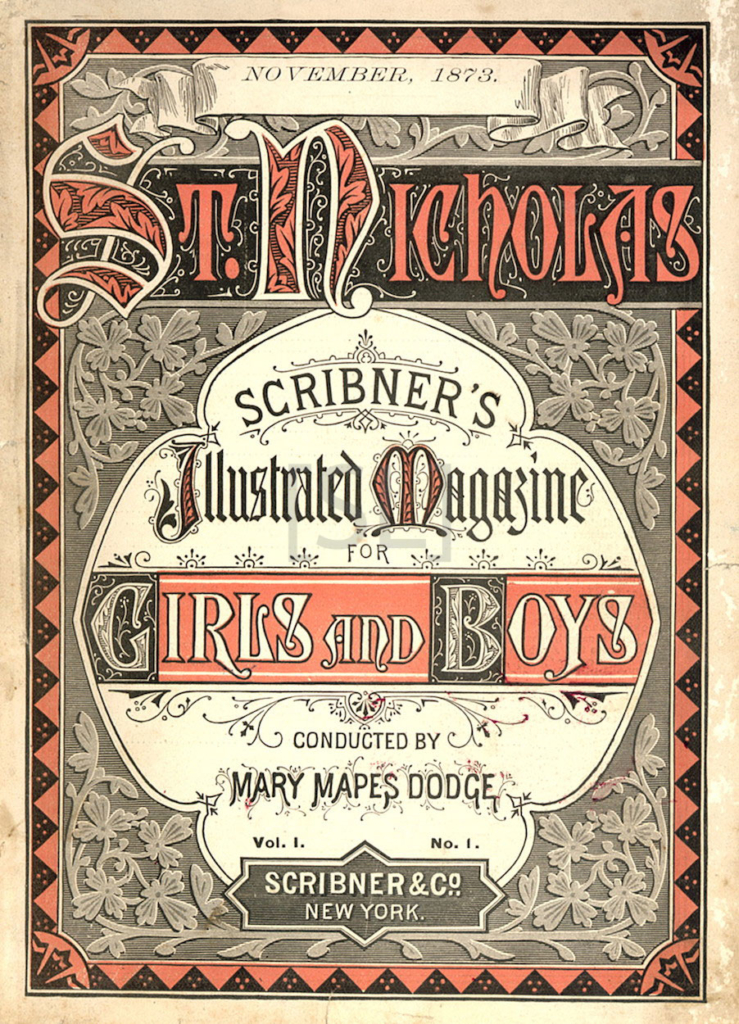

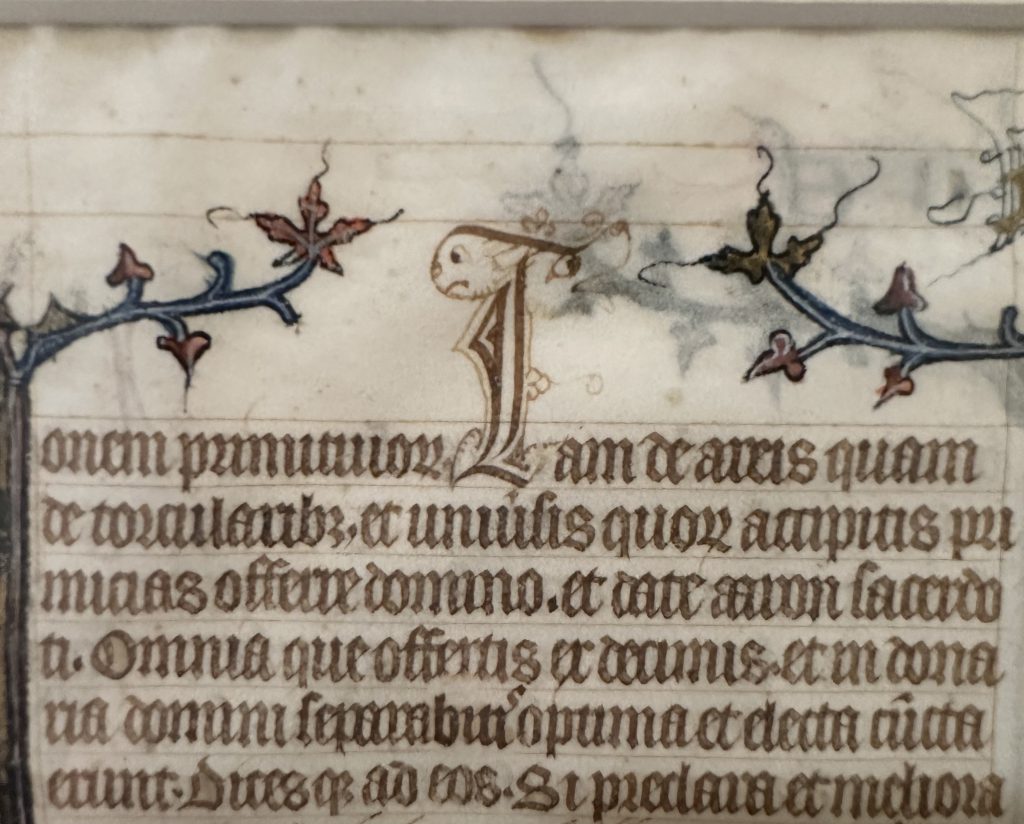

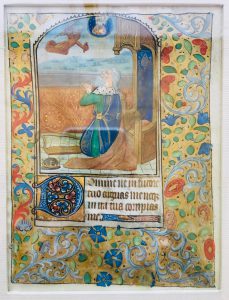

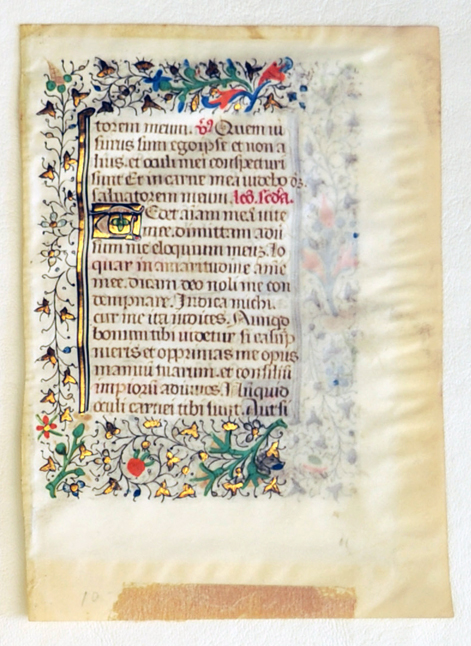

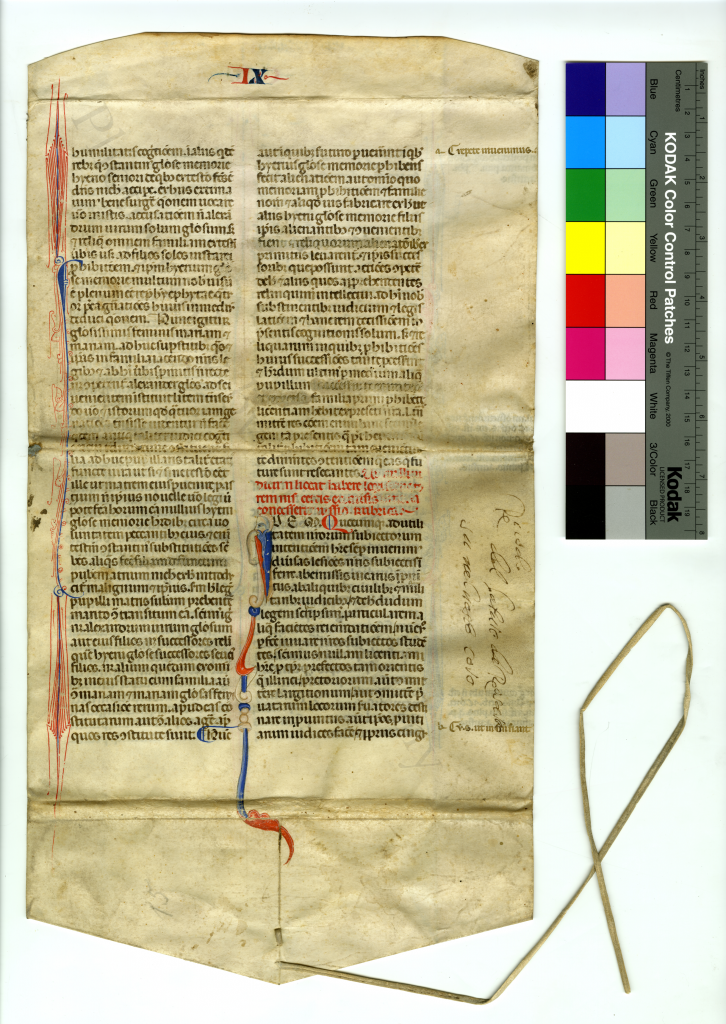

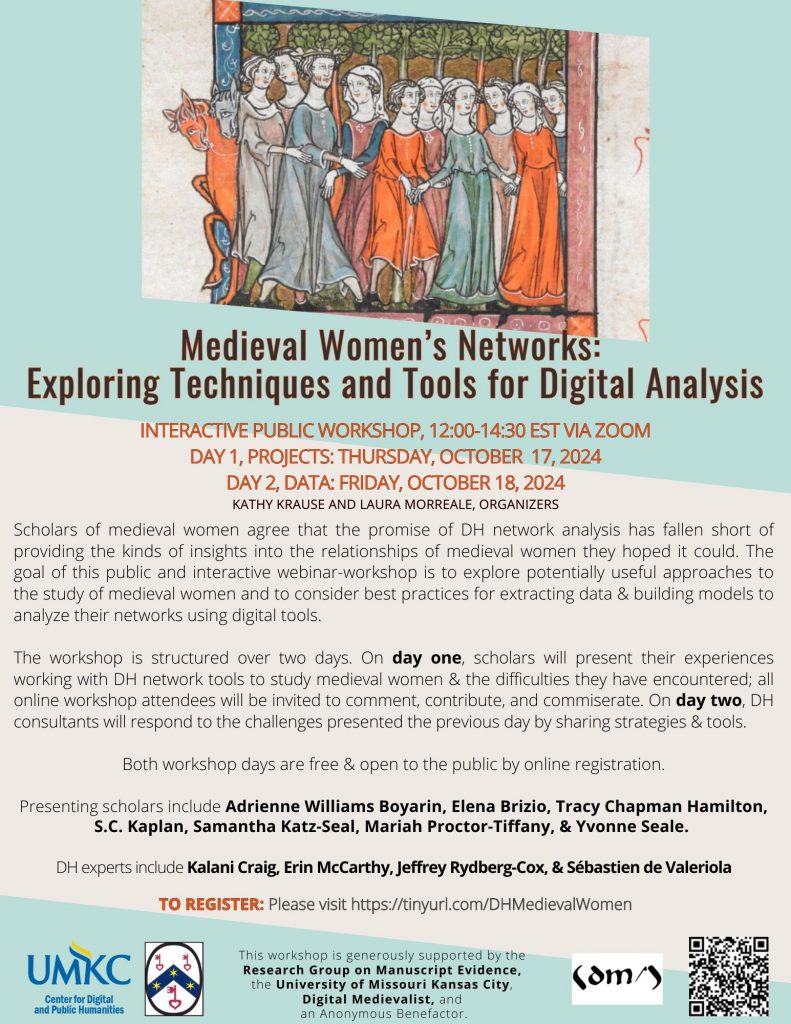

The Periodical Collection of Steven Lomazov, St. Nicholas: Scribner’s Illustrated Magazine for Girls and Boys, Front Cover (November 1873), via https://www.americanmagazinecollection.com/st-nicholas-scribners-illustrated-magazine-for-girls-and-boys-2/.

By special invitation, the Research Group on Manuscript Evidence prepares to visit the private collection of Dr. Steven M. Lomazow — neurologist, book-collector, member of The Grolier Club, author, bibliographer, raconteur, and curator of exhibitions from his collection assembled over half a century. By design, this in-person visit by the RGME to his home in West Orange, New Jersey, might gather other Princeton bibliophiles and students, as our organization combines interests, resources, and organizational skills with other groups in the Princeton area and beyond, according with our traditions for in-person and online events alike.

Mindful also of responsibility to our wider audience, as customary, the RGME will provide a hybrid approach to this occasion, with a virtual component for part of the curated visit, so that parts of our wider community might attend from a distance by Zoom allowing for discussion and feedback.

Grateful for the invitation, we look forward to the visit with its opportunity for a curated tour of an extraordinary collection for many interests assembled over more than fifty years.

The Plan on the Day

We aim to arrive at the Lomazow Collection about 11:00 or 11:30 am EST (GMT-5), mindful of traffic conditions between our base at Princeton (or elsewhere for other attendees) and the location of the collection. The online component of the visit might commence at about 12:30 pm, in time for the introduction to the collection.

First, Dr. Lomazow and his wife will host a welcoming repast catered at home from a renowned bagel shop. We would ask attendees for dietary requirements.

Next, Steven will give an introduction to the collection, the materials, and their discoveries. This account would set the stage by describing the collection, how it grew, what it contains, how widely it reaches into spheres of history, literature, popular culture, and more, and how it is arranged — by groups of materials and by their size, each in alphabetical order for ease of discovery and consultation.

Then we would be able to visit the different rooms, examine their original materials, ask questions, and enter into conversations about the varied aspects of these original sources and their contexts. Thus we might learn from the materials and from each other while engaging with the original sources. Whether in person or virtually, we might count those encounters in real time as Break Out Rooms for the visit, with tailored focus for specific items, genres, and subjects.

We would end at about 5:00 pm, although perhaps some of us might remain for discussion until about 7:00 pm. The span is subject to exploration governed by numbers and interests of attendees.

For transportation from Princeton and back again, we could explore alternatives. Depending on interest and timetables, some of us might wish to drive; depending on numbers, transportation might be arranged. Please let us know your preferences and watch this space for developments as the preparations advance.

What would you like to see? Given this generous opportunity, it might be difficult to single out specific magazines, dates, or genres, because the range of the collection is so extraordinarily varied, with something for almost everyone’s taste, and with very much for historical and cultural study. What might you choose?

The Collector

Steven Lomazow, M.D., is a board-certified neurologist in practice for 43 years.

His published works on bibliophilic and related subjects include series of reference works, celebrations of the collection, and monographs on presidential medical-historical subjects.

Looking forward to conversations with and feedback from our varied audience, both expert and general, Dr. Lomazow offers this special occasion with the RGME for opportunities to examine his varied collections and learn about them, in conversation with the knowledgeable collector. A variety of publications, in print and online, present the materials and reference perspectives on their context.

Books, Blogs, Catalogues, Exhibitions, and Virtual Exhibitions

-

- Magazines and the American Experience:

Highlights from the Collection of Steven Lomazow, M.D.

americanmagazinecollection.com

- Magazines and the American Experience:

- American Periodicals: A Collectors’ Guide and Reference Manual (West Orange, New Jersey: Lomazow, 1996)

- The Great American Magazine: Adventures in History. Selections from The Steven Lomazow Collection of American Periodicals (West Orange, New Jersey: Lomazow, 2014)

- Steven Lomazow et al., Magazines and the American Experience: Highlights from the Collection of Steven Lomazow, M.D. A Catalogue published in conjunction with an exhibition held at The Grolier Club, January 20 – April 24, 2021 (New York: The Grolier Club, 2020).

“The exhibition is presented in two sections, beginning with a chronological history of American magazines from 1733 to the present. The second is devoted to a broad spectrum of genres which address the areas of popular culture that became a major focus of American magazines in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, including American artists and humorists, the ongoing struggle of African Americans to achieve equality, a salute to our national game of baseball, and the development of radio, television, and motion pictures.”

- Companion Virtual Exhibition at the Grolier Club: American Magazines

Also:

- Steven Lomazow (with Eric Fettman), FDR’s Deadly Secret (New York: BBS Publications, 2009)

- FDR Unmasked: 73 Years of Medical Cover-ups That Rewrote History (Amsterdam: Lugler Publications, revised edition, 2024). FDRUNMASKED.com

What is in Store?

Dr. Steven puts it succinctly. The collection contains

“Thousands of exquisitely rare and historically important items.

“The collection contains virtually every major magazine highlight ever published from the eighteenth century to the present and covers virtually every topic- literature, politics, technology (TV, Radio, Movies, Aviation etc). It also includes by far the largest collection of first issue pulp magazines (over 850) in existence. Any institution or individual that acquires it will immediately become one of the leading repositories of American popular culture. . . . There are hundreds of feet of shelves occupied by bound volumes and individual issues.”

— Magazine Collection for Sale (2011)

Many items are destined for exhibition and perhaps transfer to other institutions. This visit offers an in-depth opportunity to examine them on display in situ in the company of the collector, who has built an exceptional collection of a variety of genres, including American magazines from their beginnings, patriotic magazines in World War II, and more.

Registration

Registration is required for attendance, whether in person or online by Zoom. Numbers of attendees for the at-home visit are limited; in case of need, we will create a Waiting List.

Registration is free. We welcome voluntary donations for our section 501(c)(3) nonprofit educational organization equipped with slim financial resources and powered principally by volunteers with donations in funds and contributions in kind. Such donations help to sustain and foster our mission and activities. Your donations may be tax-deductible to the fullest extent permitted by law.

Please register through the RGME Eventbrite Portal, which presents all our Collections of events. Here are the ways to register for the visit in hybrid formats.

1) To attend In Person

2) To attend Online by Zoom

After you register for online attendance, you will be sent the Zoom Link a few days before the event.

Questions or Suggestions?

Do you have special requests for materials you would like to see in the collection during the visit? Questions for the collector? Would you like to share your experiences with growing up with American magazines?

Please Contact Us or visit

- our FaceBook Page

- our Facebook Group

- our Twitter Feed (@rgme_mss)

- our Bluesky nest @rgmesocial.bluesky.social)

- our LinkedIn Group

- our Blog on Manuscript Studies and its Contents List

We look forward to hearing from you.

*****

The Periodical Collection of Steven Lomazov, St. Nicholas: Scribner’s Illustrated Magazine for Girls and Boys, Front Cover (November 1873), via https://www.americanmagazinecollection.com/st-nicholas-scribners-illustrated-magazine-for-girls-and-boys-2/.

Note on the Image. The long-lived St. Nicholas Magazine was launched in 1873, with the redoubtable Mary Mapes Dodge (1831–1905) as its first editor and many prominent authors as contributors during its period of circulation until 1940. From the Lomazow Collection, we glimpse the cover of the first issue.

Of the editor’s skills it is related:

She was able to persuade many of the great writers of the world to contribute to her children’s magazine – Mark Twain, Louisa May Alcott, Robert Louis Stevenson, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, William Cullen Bryant, Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., Bret Harte, John Hay, Charles Dudley Warner, Elizabeth Stuart Phelps Ward, and scores of others. One day, Rudyard Kipling told her a story of the Indian jungle; Dodge asked him to write it down for St. Nicholas. He never had written for children, but he would try. The result was The Jungle Book.

Of especial interest to the RGME in its Anniversary Year is the first appearance in this magazine of the tale of The Little Red Hen, in its original form in a publication in English. This fable, in its original unadulterated form, serves as useful model for the RGME as goal for collaborative work and its practices or processes.

*****

2025 International Medieval Congress at Leeds: Call for Papers

August 1, 2024 in Announcements, Call for Papers, International Medieval Congress, Leeds, Manuscript Studies

2025 International Medieval Congress

at Leeds:

Call for Papers

“Manuscripts as Worlds of Learning”

(2 Sessions + Roundtable)

32nd Annual IMC

Monday to Thursday 07–10 July 2025

(with In-Person and Virtual Components)

Deadline for your Proposals for Papers: 5 September 2024

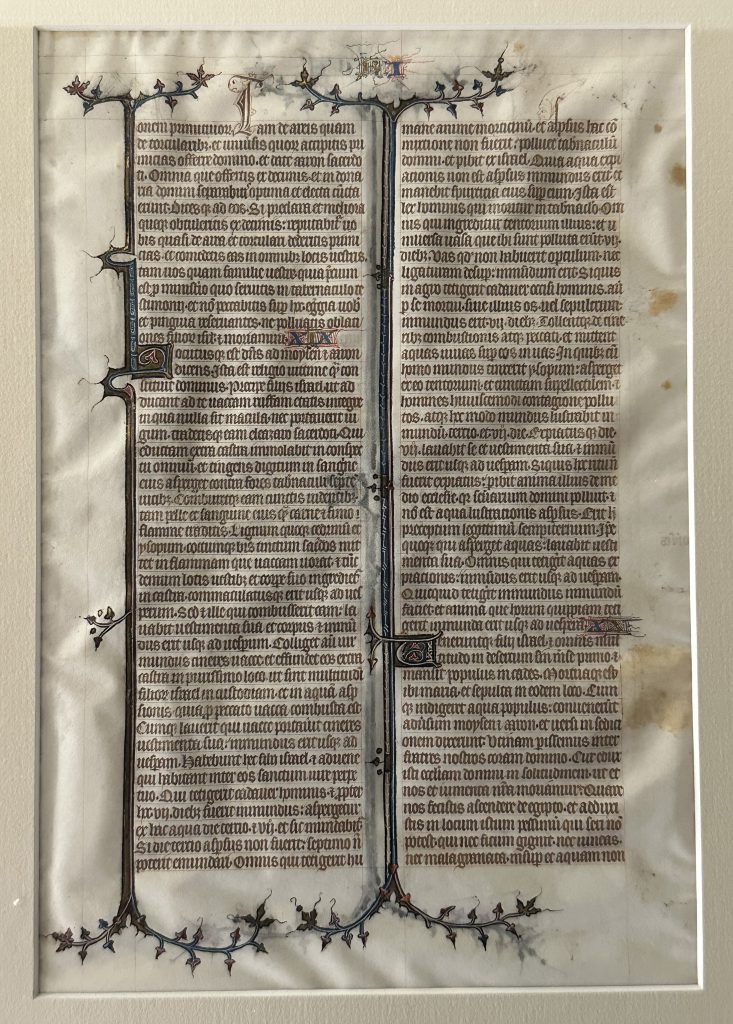

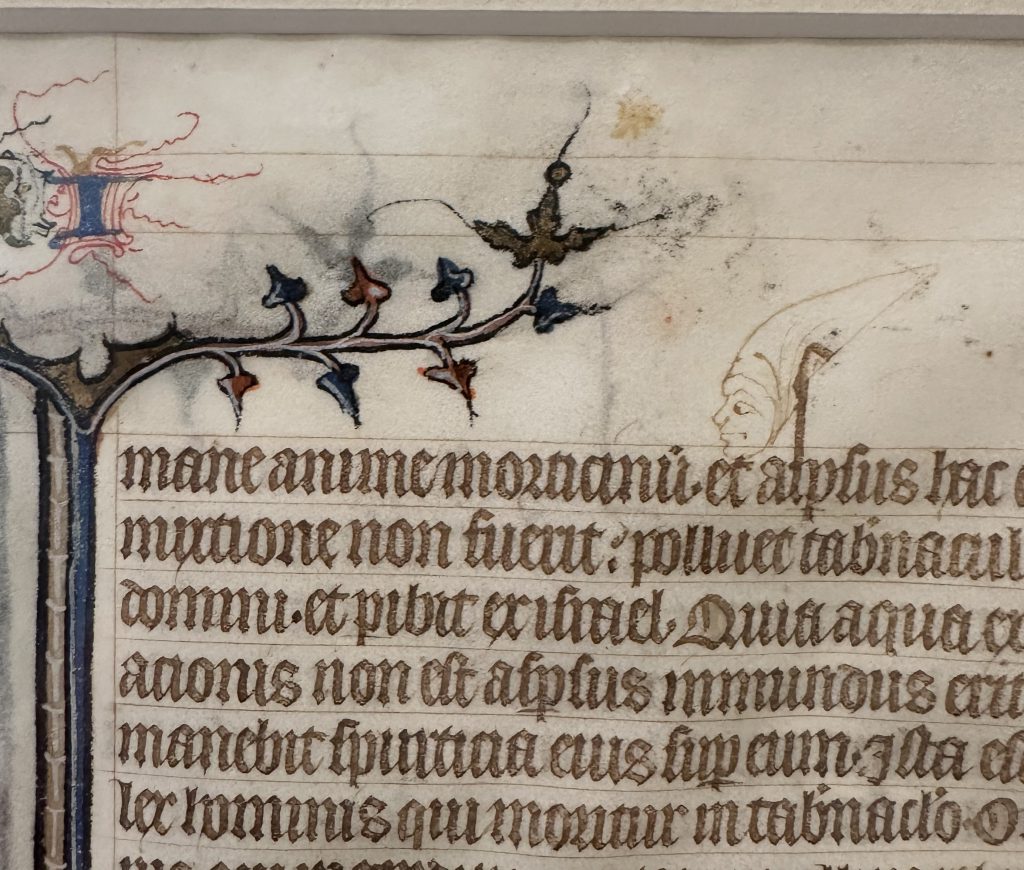

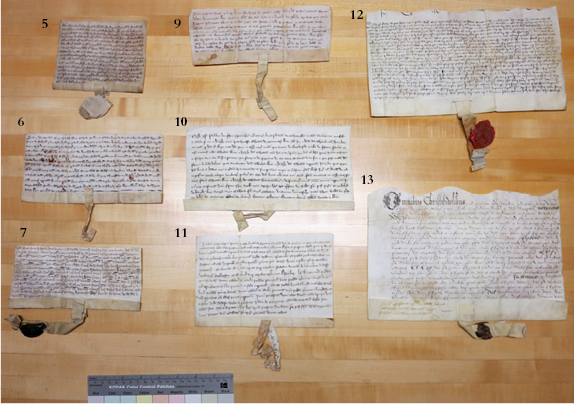

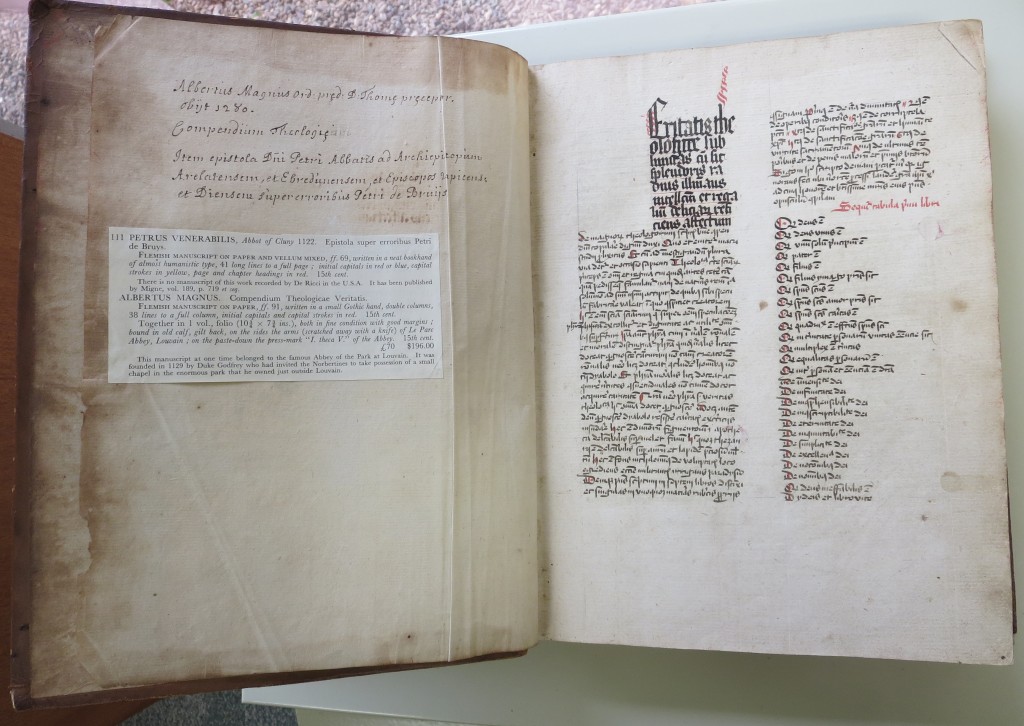

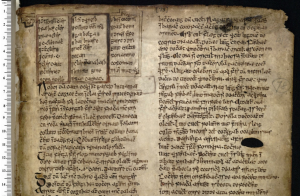

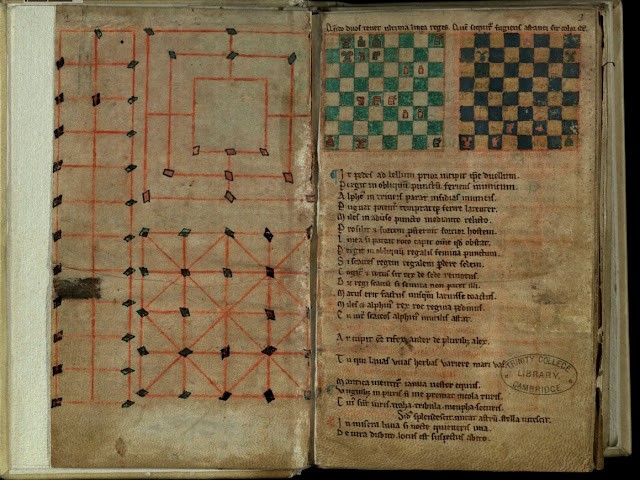

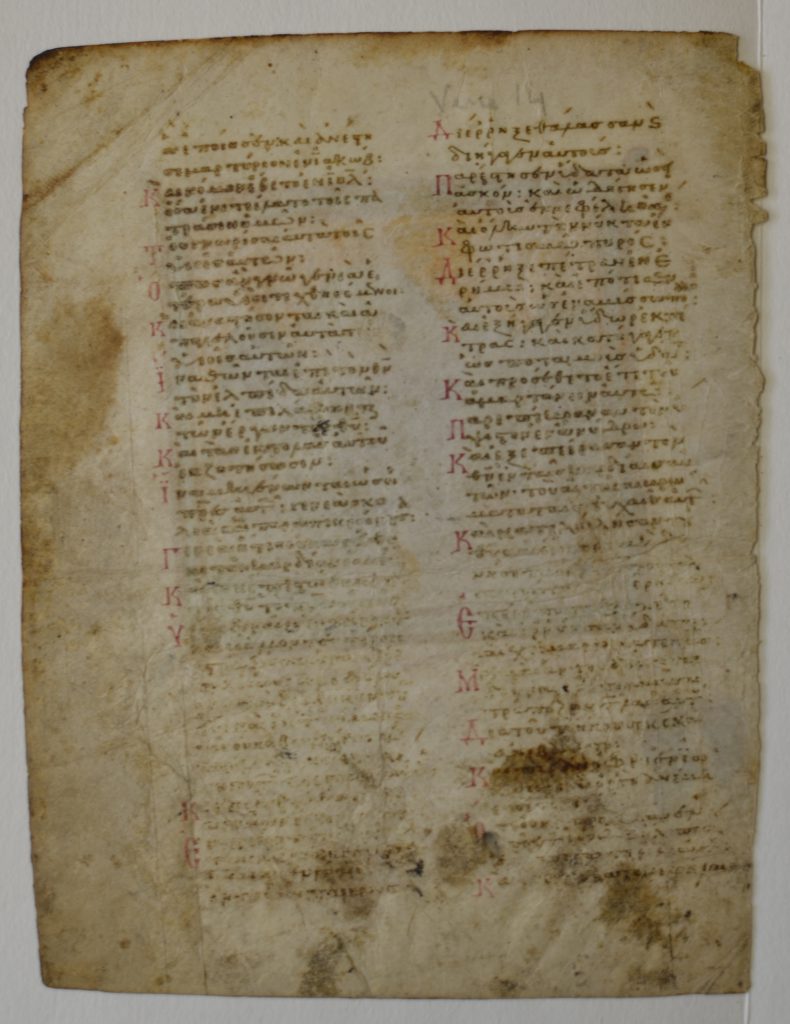

Dublin, Royal Irish Academy, MS 23 E 25, p. 73, top. Image via https://codecs.vanhamel.nl/Dublin,_Royal_Irish_Academy,_MS_23_E_25 via Creative Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

[Posted on 1 August 2024, with updates]

Building upon the successful completion of our RGME Inaugural Session at the International Medieval Congress (IMC) at the University of Leeds in July 2024, we announce the Call for Papers (CFP) for our activities at next year’s Congress.

For information about the Congress, see

Note that the general deadline for individual papers without specified sessions in a general pool is 31 August 2024.

The deadline for proposals for our RGME-sponsored Sessions is 5 September 2024. Please send your proposals directly to us as organisers; we will select the programmes by their deadline of 30 September 2024. (Instructions below.)

“Worlds of Learning” at Leeds in 2025

Next year’s Thematic Focus for the IMC is “Worlds of Learning”. The broad scope is described in the general Call for Papers: IMC 2025 – ‘Worlds of Learning’.

We invite you to submit proposals for a set of interlinked events planned for the Research Group on Manuscript Evidence (RGME) to focus on the power and potential of manuscripts to contain, convey, and embody worlds of learning within their span. In effect, given their structure and contents, as we approach them as beholder, user, reader, student, teacher, or admirer, they may carry worlds in our hands.

How might medieval manuscripts do so, variously for their medieval audience, later intermediaries, and our own times? How might and do they function as “Worlds of Learning” in their own right/write? We explore.

Update (14 August 2024): As interest grows, we plan several sessions for the 2025 IMC.

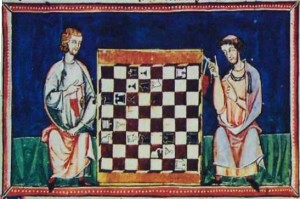

In another post, we present a Session with Papers devoted to “Game Knowledge and Knowledge of Games”, which follows up a strand in our RGME Inaugural Session this year.

Here we present a suite of events containing two Sessions with Papers accompanied by a Round Table with Discussion, all dedicated to “Manuscripts as Worlds of Learning”.

Read the rest of this entry →

Tags: 'Commonplace Books', Authority Texts, Biblical Commentaries, Classbooks, History of Pedagogy, Instruments of Learning, International Congress on Medieval Studies, International Medieval Congress, Lebor na hUidre (LU), Legal Commentaries, Manuscript Miscellanies, Manuscript studies, Pedagogy, RIA MS 23 E 25, Worlds of Learning

No Comments »