Episode 12: Vajra Regan on Engraved Magic and Astrological Images

May 30, 2023 in Manuscript Studies, Research Group Speaks (The Series), Uncategorized

The Research Group Speaks

Episode 12

Saturday 12 August 2023 online

1:00–2:30 pm EST (GMT-5) by Zoom

“The Sources of the Engraved Magic and Astrological Images

in the Book of Sigils (Liber Sigillorum)

and the Ghāyat al-Hakīm (The Goal of the Wise)”

Vajra Regan

[Posted on 30 May 2023, with updates]

We invite you to attend Episode 12 in our series.

Our Associate, Vajra Regan will speak about the subject of his new joint publication, which has now appeared in early August 2023, a few days before our event. Vajra’s presentation about this project and the process towards its publication explores explore the subject of visual imagery for astrological magic as transmitted across time, languages, and cultural settings.

Over the years, Vajra has presented papers and organized Sessions for the RGME and our co-sponsor, the Societas Magica, since 2019.

These activities allow us to continue to learn about Vajra’s research as it continues to expand, to deepen, and to unfold. We are glad for his offer to talk with us for the Episode.

Vajra’s Plan for the Episode, in his Own Words

The Title

“The Sources of the Engraved Magic and Astrological Images

in the Book of Sigils (Liber Sigillorum)

and the Ghāyat al-Hakīm (The Goal of the Wise)”

The Abstract

The twelfth century saw the translation into Latin of a group of Arabic texts on astrological image magic with titles such as The Book of Planets (Liber Planetarum), The Stations of the Cult of Venus (De stationibus ad cultum Veneris), and The Book of Venus (Liber Veneris). These texts, usually attributed to Hermes or one of his retinue, provided detailed instructions relating to the liturgy of the planets and the fabrication of engraved astrological images or talismans. Unfortunately, in the following centuries, they were systematically suppressed to such an extent that today many survive in only one or two late manuscripts.

Although long recognized as important to the history of learned magic in the West, these texts have so far received little scholarly attention. Consequently, the precise nature and extent of their influence have remained largely a matter of conjecture.

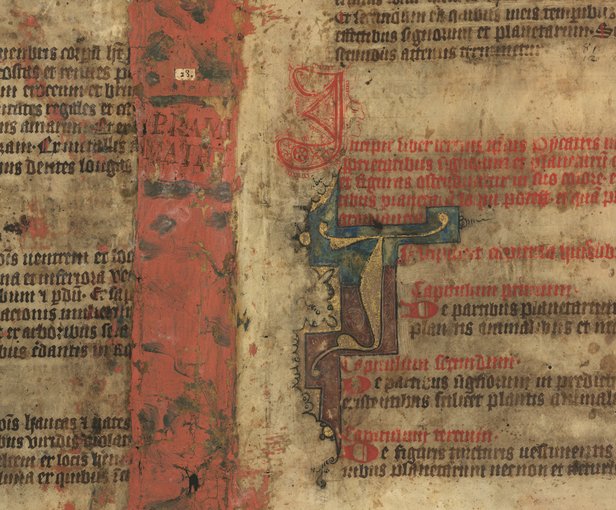

Martin, Slovakia, Slovak National Library, Fragment of the Picatrix, circa 1400 CE. Image Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

As part of the series “The Research Group Speaks,” I examine the Hermetic Liber planetarum and its connection to two important books of magic, the Liber sigillorum of Techel and the Ghāyat al-Hakīm (“The Goal of the Wise”) or Picatrix. The talk both summarizes and expands on the research that Lauri Ockenström and I have presented in our recent article, “The Hermetic Origins of the Liber sigillorum of Techel” (The Journal of Medieval Latin 33 [2023]).

The Liber sigillorum is a twelfth-century treatise on precious stones and the images of power engraved on them. Although little known today, it was arguably the most widely copied lapidary of the late Middle Ages, second only to the Liber lapidum of Marbode of Rennes (ca. 1035– 1123); moreover, like the Liber lapidum, Techel’s treatise exerted a broad influence that extended well beyond the lapidary literature, narrowly defined. It was given serious consideration by the scholastic encyclopedists, by philosophers such as Albert the Great, and by medieval medici such as Peter of Abano. Thomas of Cantimpré (ca. 1200 – 1270) included a version in his Liber de natura rerum through which it was transmitted to Konrad von Megenberg (1309–1374), author of the Buch der Natur, the first German-language natural history, and then to Paracelsus (ca. 1493 – 1541). The physician and astrologer Camillo Leonardi included no less than three different versions of Techel in his Speculum lapidum (1502).

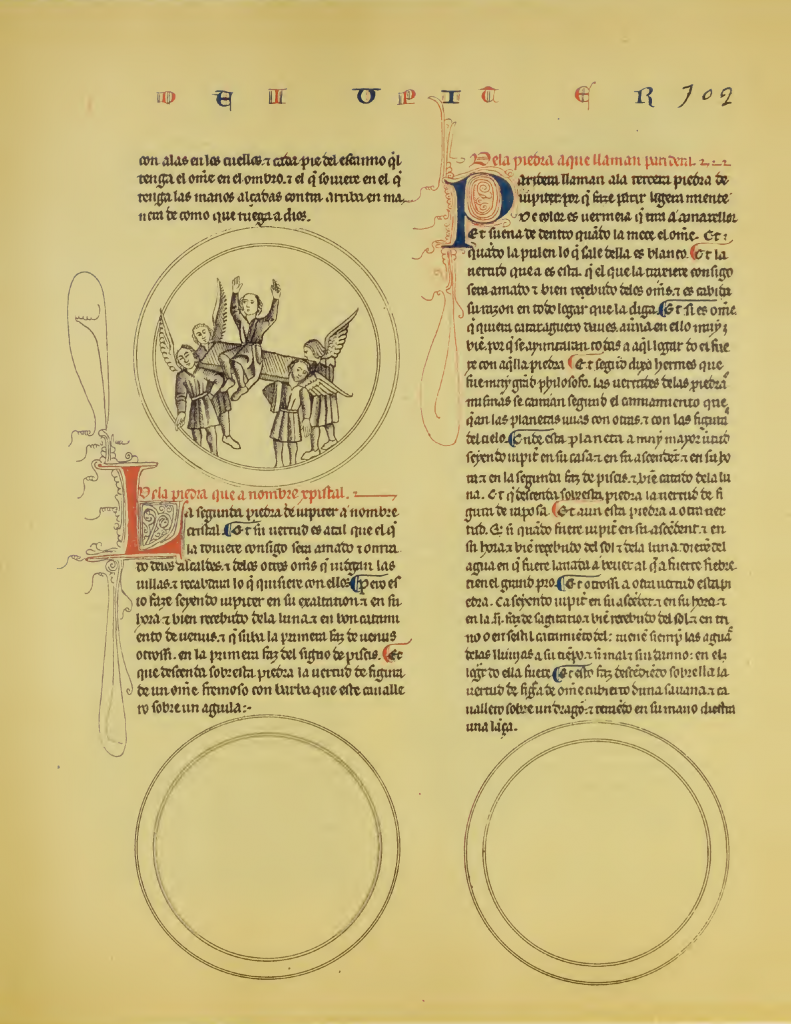

Lapidario del Rey D. Alfonso X: Codice original (1881), folio 1r detail. Image via Creative Commons via https://ia802202.us.archive.org/14/items/lapidariodelreyd00alfo/lapidariodelreyd00alfo.pdf.

The versions published by these authors represent only a fraction of the whole. Numerous others may be found spread across nearly a hundred manuscripts preserved in libraries around the world. Nevertheless, despite its popularity, the Latin tradition of the Liber sigillorum has never been the subject of systematic study, and many questions still surround the origins of the text. While it is generally agreed that core parts of the early text are translations, scholars have offered conflicting opinions as to the original language. David Pingree believed that a Greek exemplar lay behind the Latin text (“The Diffusion of Arabic Magical Texts in Western Europe,” in La diffusione delle scienze islamiche nel Medio Evo europeo [1987]), while Katelyn Mesler, noting certain similarities with the Picatrix (Ghāyat al-Hakīm) has argued for an Arabic original (“The Medieval Lapidary of Techel/Azareus on Engraved Stones and Its Jewish Appropriations” in Aleph 14:2 [2014]).

The images in the Liber sigillorum are indeed remarkably similar to those in the Ghāyat al-Hakīm; however, their origin lies in the Latin translation of the Liber planetarum, a copy of which is preserved in a unique manuscript in the National Library of Florence (Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, II.III.214). This origin is proven by a comparison of the images and the language of their descriptions. A comparison of the images also suggests that the lost Arabic original of the Liber planetarum was one of the sources of the Ghāyat al-Hakīm. A survey of other Hermetic texts translated into Latin in the twelfth century, and belonging to the same group as the Liber planetarum, suggests that they too might transmit some of the sources of the Ghāyat.

Martin, Slovakia, Slovak National Library, Fragment of the Picatrix, circa 1400 CE. Image Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image of “Jupiter Enthroned” (“Olympian Zeus”) in the Lapidary of Alfonso X

Lapidario del Rey D. Alfonso X: Codice original (1881), folio 102r. Image via Creative Commons via https://ia802202.us.archive.org/14/items/lapidariodelreyd00alfo/lapidariodelreyd00alfo.pdf.

Note on the image

El Escorial, Real Biblioteca de San Lorenzo, MS H. I. 15, fol. 102r. The manuscript, known as the Lapidary of King Alfonso Xc, was commissioned in 1253 by Alfonso X “the Wise” or Alfonso X de Castilla (1221–1284), King of Castile, León, and Galicia.

The image here comes from the 1881 color facsimile of the El Escorial manuscript, Lapidario del Rey D. Alfonso X: Codice original, ed. D. José Fernandez Montaña (Madrid, 1881); freely accessible online via:

Folio 102r occurs in the online pdf variously as page 267 (Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes) or page 241 (archive.org via the Getty Institute).

A recent printed facsimile: Lapidary of Alfonso X the Wise, an “Astrology commissioned by the Spanish king Alfonso the Wise” in 1253 on “the healing effects of stones and gems in luminous miniatures” (Madrid: Edilan, 1982). “This treatise commissioned by the King is concerned with the magical and medical importance and effect of gems and other stones in connection with astrology”.

For an English edition of the Lapidario, see The Lapidary of Alfonso X the Learned, edited by Ingrid Bahler and Katherine Gyékényesi Gatto (University Press of the South, 1997); ISBN 1-889431-15-X.

Jupiter Enthroned. Lapidario del Rey D. Alfonso X: Codice original (1881), folio 102r top left. Image via Creative Commons via https://ia802202.us.archive.org/14/items/lapidariodelreyd00alfo/lapidariodelreyd00alfo.pdf.

*****

A Handout for the Presentation

Vajra has prepared a Handout for this Episode. Incorporating materials from his presentation, including Tables and Images, you can freely download the Handout as a preview and souvenir here:

*****

Registration for the Episode

Episode 12 in the online series of “The Research Group Speaks” is planned for Saturday 12 August 2023, via Zoom, at 1 pm EST (GMT – 5) for about 1 1/2 hours, with discussion and Q&A. You are welcome to join us.

If you wish to attend, please register here:

Lapidario del Rey D. Alfonso X: Codice original (1881), folio 102r top left. Image via Creative Commons.

Registration via the RGME Eventbrite Collection

Registration for this Episode

Registration is free.

We offer the option for Registration with a Donation, which we welcome. Donations, which may be tax-deductible, help us to continue with our activities and sustain our mission for an organization principally powered by volunteers.

After registration, the Zoom link will be sent a few days before the event.

If you have questions or issues with the registration process, please contact director@manuscriptevidence.org.

We thank you who have registered and given an optional Donation.

Future Episodes

Future Episodes are planned. See:

Episode 13 is scheduled for Saturday 23 September 2023 online via Zoom. See:

Suggestion Box

Please leave your Comments or questions here, Contact Us, or visit

- our FaceBook Page

- our Twitter Feed (@rgme_mss)

- our Blog on Manuscript Studies and its Contents List

Donations and contributions, in funds or in kind, are welcome and easy to give. See Contributions and Donations.

We look forward to hearing from you.

Lisbon, Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga: The mid 15th-century Saint Vincent Panels, attributed to Nuno Gonçalves. Image (https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/3a/Nuno_Gon%C3%A7alves._Paineis_de_S%C3%A3o_Vicente_de_Fora.jpg) via Creative Commons.

*****