Vellum Binding Fragments in a Parisian Printed Book of 1598

June 30, 2020 in Documents in Question, Manuscript Studies

Pieces of an Early 16th-Century French Legal Document

Reused as Vellum Supports or Guards

in the Quarto Binding of

Henry de Suberville’s L’Henry-Metre

Printed in Paris in 1598

Manuscript Binding Fragments Remaining In Situ

[Posted on 30 June 2020, with updates]

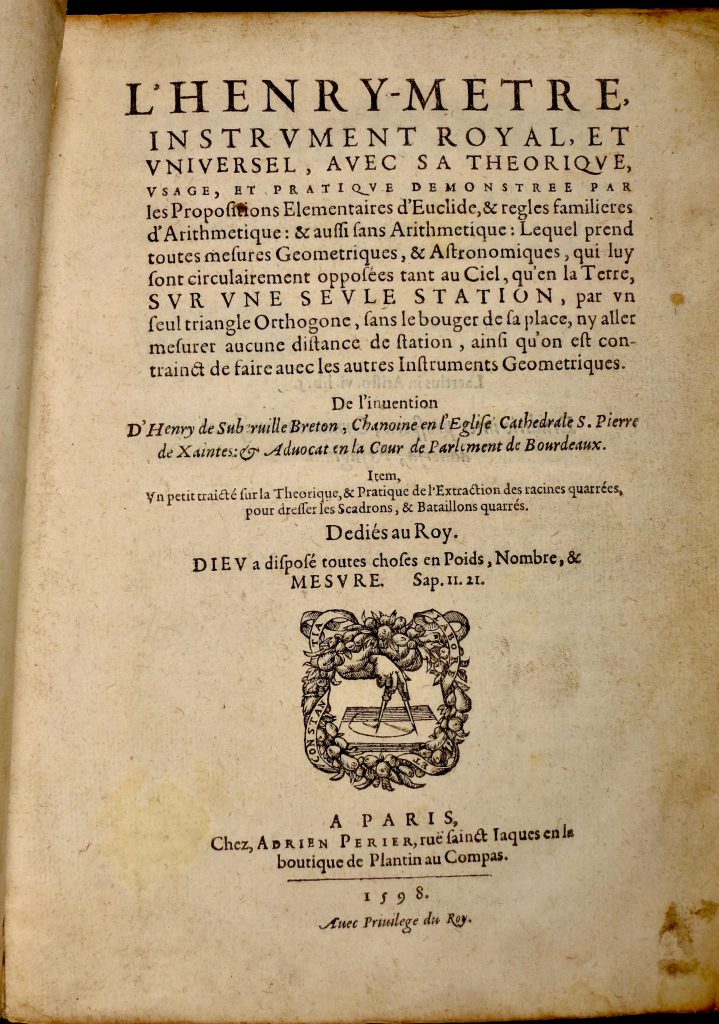

Smeltzer Collection, Henry de Suberville, ‘L’Henry-metre’ (1598), Title Page.

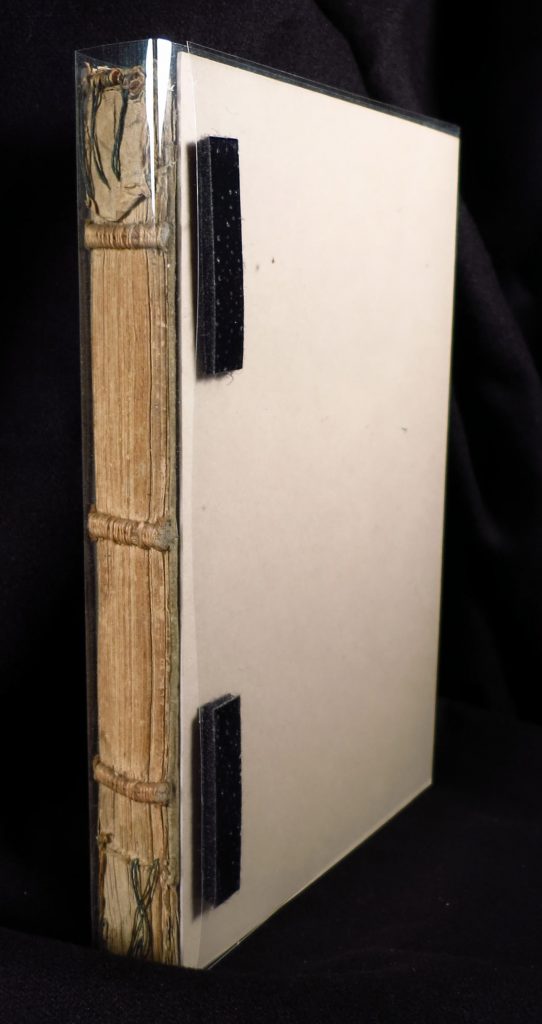

Smeltzer Collection, Henri de Suberville (1598), Spine View as Preserved.

With thanks to the owner, our Associate, Ronald K. Smeltzer, we observe some recycled vellum stiffeners which still stand in situ in a scientific book by the author and inventor Henry de Suberville, printed in Paris in 1598 by Adrien Perier. All the photographs here are Ronald’s, reproduced with permission. The volume has lost the boards and any covering of its former cover, but it retains elements of the binding, including the stitching and some stiffeners repurposed from earlier hand-written material. Our purpose here is to examine and illustrate the reused binding fragments in their settings.

Inspired by The Caxton Club/Bibliographical Society of America Symposium on the Book held in April 2015 on “Preserving the Evidence: The Ethics of Book and Paper Conservation”, Ronald has published a concise report (freely downloadable) about the volume and his approach to conserving and conserving it.

- Ronald K. Smeltzer, “Preserving the Evidence: A 16th-Century Book Absent Its Binding”, Caxtonian: Journal of the Caxton Club, 18:9 (September, 2015), 1–3.

His Figure 5 (shown at the left) shows the volume in 3-quarter view, from the front and the spine, with minimal intervention. Here, we learn, is “Suberville’s treatise in its polyester enclosure with hook-and-loop fasteners, showing the intact structure of the spine, including the remains of head and tail bands and cords”.

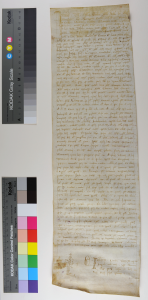

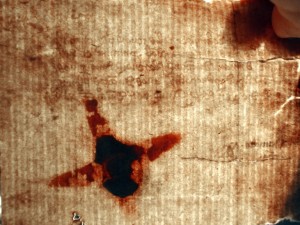

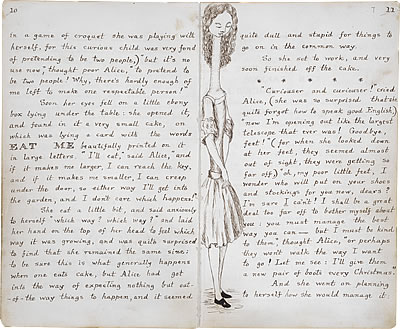

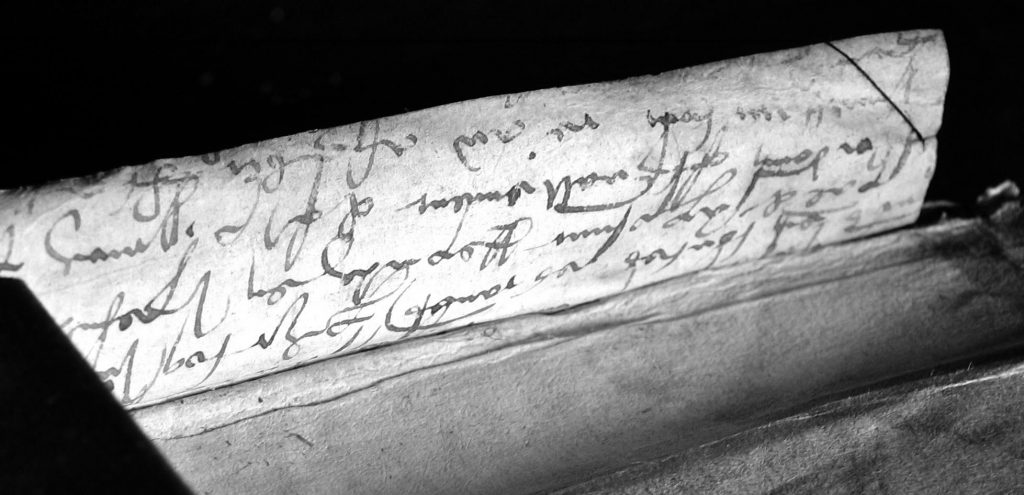

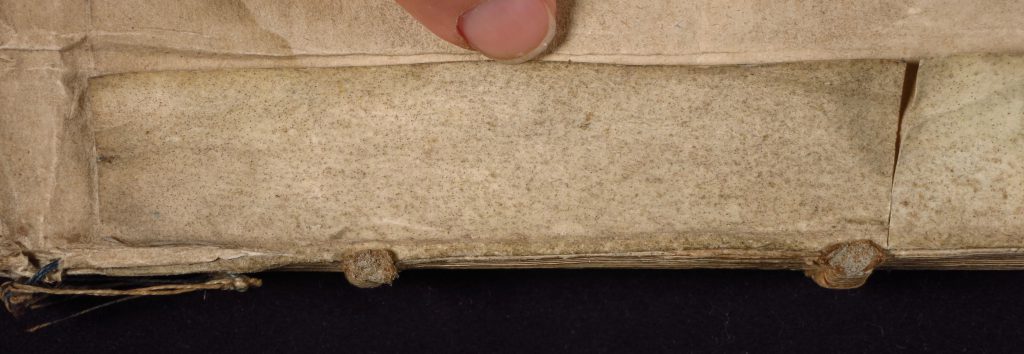

Moreover, there survive further remnants from the former state of the volume. “Apparently as guards, vellum flaps are present, but not visible in Fig. 5, on both sides of the spine. Very old handwriting, not decipherable by me, is on the inner side of the vellum pieces, as illustrated in Fig. 6.”

Figure 6 (shown below) shows a reused vellum fragment as it fits in the volume, with the tops of the original script turned to the gutter and spine of the binding.

Smeltzer Collection, Henri de Suberville (1598): Vellum Support, as shown in Smeltzer (2015), Figure 6.

As Ronald observed, “Considering the interesting visible and apparently contemporary structure of this late 16th-century book, it seems appropriate to leave it as-is.”

We agree. See, for example, Physical Evidence and Manuscript Conservation: A Scholar’s Plea (1994) by our Director, and posts throughout our blog, listed in the Contents List.

The Volume ‘As Is’

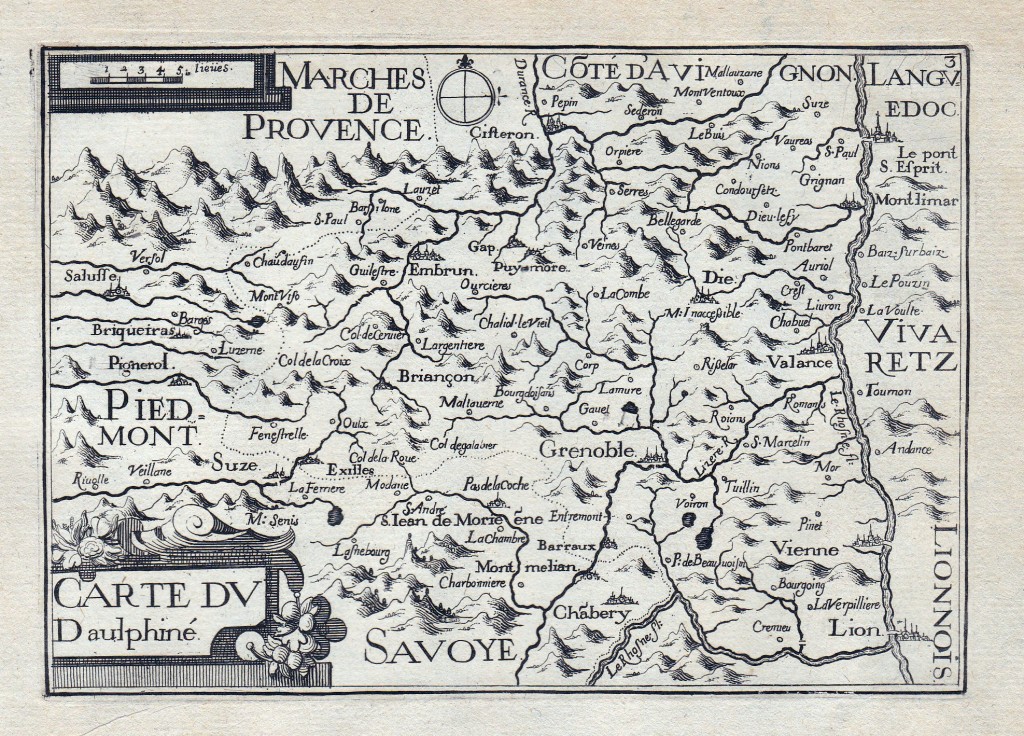

The volume is a copy of Henry de Suberville’s L’Henry-Metre, Instrument Royal et Universal avec sa théorique, usage et pratique démontrée . . . (Paris: Adrien Perier, 1598), lacking its former binding. The title-page lists the printer’s address as rue sainct Iacques en le boutique de Plantin au Compass, on a notable street in Paris in the Latin Quarter, among other booksellers and printers. Adrien Périer had marred Madeleine (or Magdalena) Plantin, daughter of Christophe Plantin and widow of Guy Beys (who died in 1595), and he came to use the Plantinian compasses as printing mark. The colophon of the volume states that the book was printed by Jamet Mettayer, printer and bookseller, that is, during the second period of Mettayer’s work in Paris (1594–1605).

We might wonder what scraps lay to hand to put to use in the sewing when the individual copies of the work received their bindings.

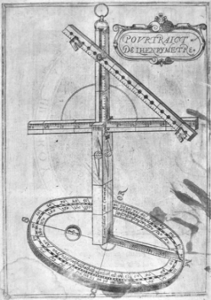

It joins Ronald’s collection of works on early scientific instruments. On an “obscure” subject, Suberville’s book presents a text on mensuration with the trigonometric device which he had invented: the HenryMetre. Its Portraict is illustrated in the book and reproduced in Smeltzer’s Figure 2 (below left). “With its circular base, both horizontal and vertical angles could be measured. Hence, it could be used for surveying, measuring heights and distances, and carrying out astronomy measurements”. Basically, the text offers a guide to the instrument.

Paris, Musée du Louvre, Department of Paintings, Henry IV, King of France in Black Dress (1610), by Frans Pourbus the Younger. Image Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Smeltzer Collection, Henri de Suberville (1598), ‘Pourtraict de l’HenryMetre’.

The book is a modest quarto. Its first half has 72 woodcut illustrations, many full page or nearly so, showing how the Henry-Meter is used and providing diagrams of the relevant geometry for calculations based upon measurements to be made with it. The second half of the text mainly considers specific problems, mathematical calculations, and tables of numbers. The 4 engraved plates include the “Pourtraict” of the device and the frontispiece portrait, by Thomas de Leu, of the dedicatee, King Henri IV (1553–1610), King of France and Navarre. (On this frontispiece, see, for example, its record in the British Museum collection.)

The Volume

The title page announces the Henry-Metre as subject, describes its abilities, names its inventor–author, Henry de Subreville Breton, and describes him as Chanoine en l’Eglise Cathedrale S. Pierre de Xaintes; & Aduocat en la Cour de Parlement de Bourdeaux. The cathedral church at which he was a canon was the former Cathédrale Saint-Pierre de Saintes in Saintes, Carente-Maritime, France. Suberville composed his text apparently during the last few years of the wars of religion in 16th-century France — to which it refers.

Smeltzer Collection, Henry de Suberville, ‘L’Henry-metre’ (Paris, 1598), Title Page.

The Spine

Apparently original, the sewing remains mostly intact.

Smeltzer Collection, Henri de Suberville (1598), Spine View as Preserved.

The Location of the Strips

It is useful to recognize how the vellum supports are integrated into the book’s structure, noting neighboring blank leaves not part of the gathering structure. The gathering formula encapsulates the structure of this unusual book:

![]()

At both front and back, a folded pair of blank paper leaves (comprising a bifolium) stands at the outer side of each gathering which has a vellum support. At the front, the vellum support encompasses gathering ã and two blank leaves before it. At the rear, the vellum support encompasses gathering H and two blank leaves following leaf H2. That the 2 blank leaves in each case are not part of the gathering structure itself is seen by their chain-lines that are vertical, and not horizontal as for the text leaves. The paper of the blanks seems to be slightly different to the touch. They carry no watermarks.

The Fragments and Their Text

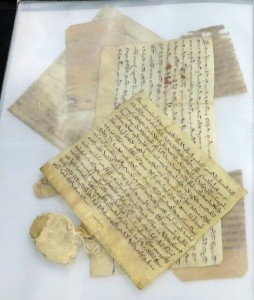

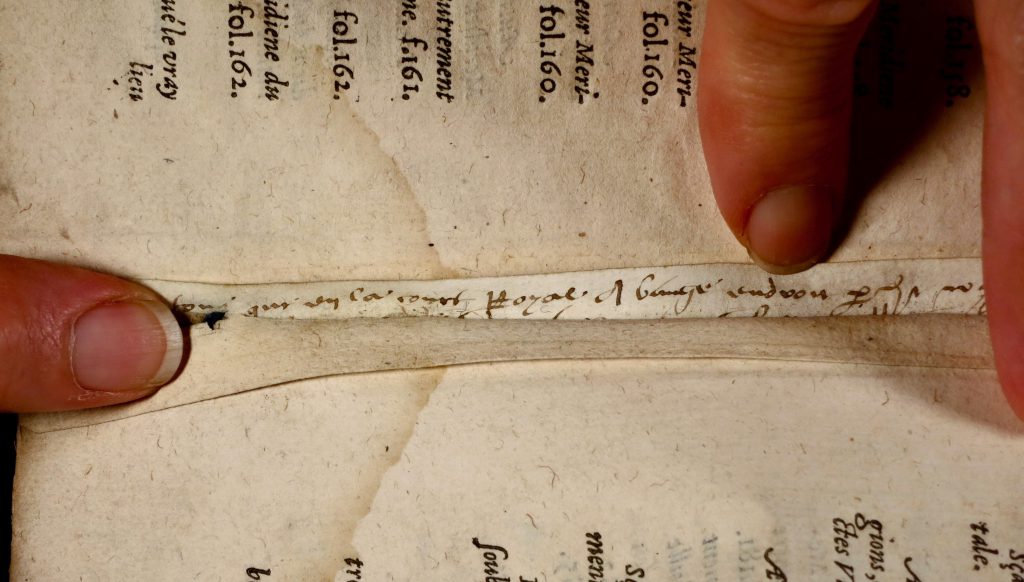

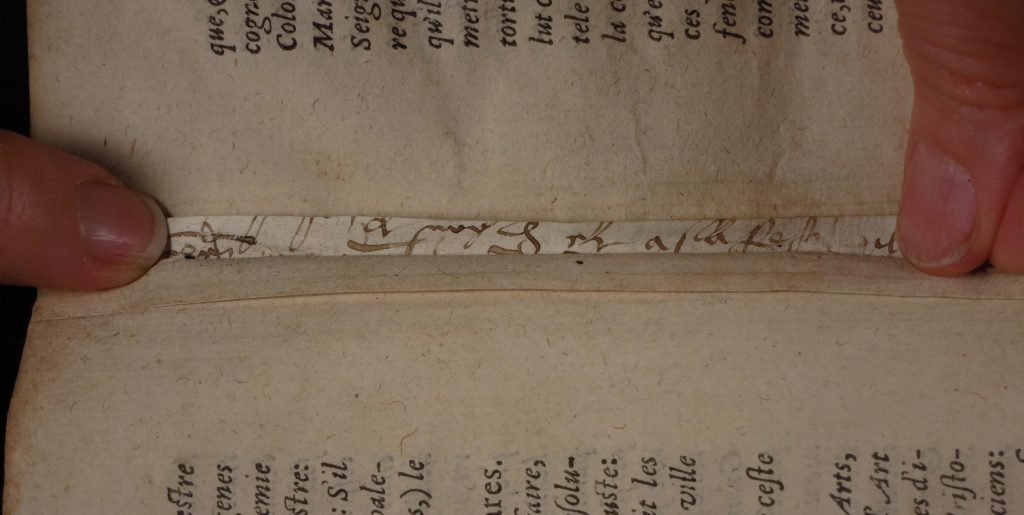

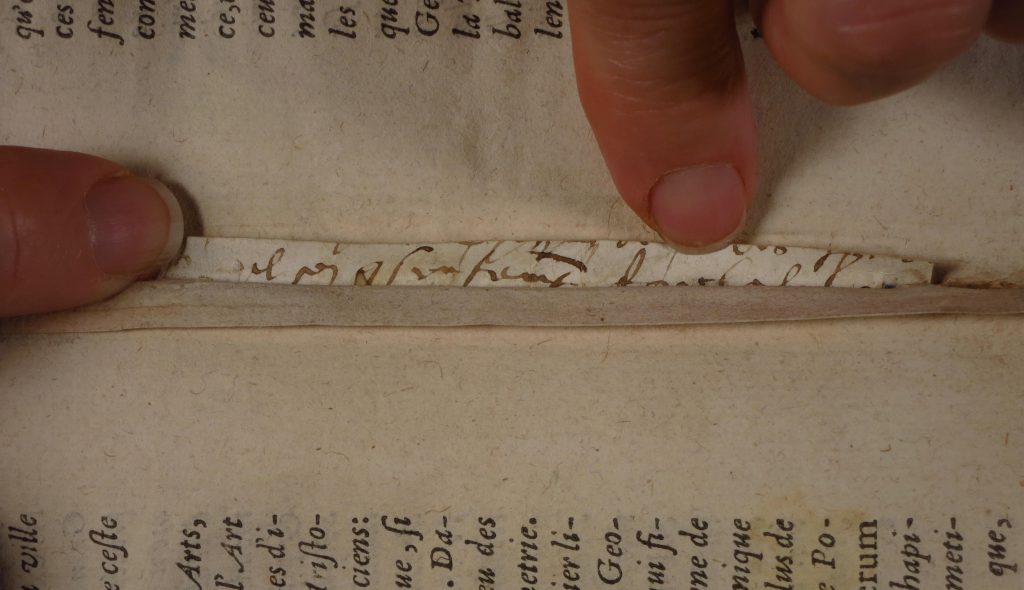

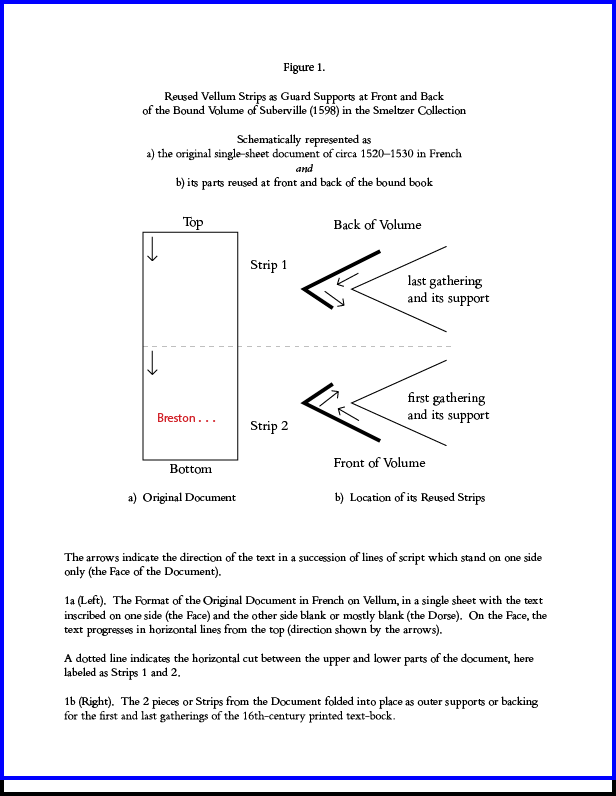

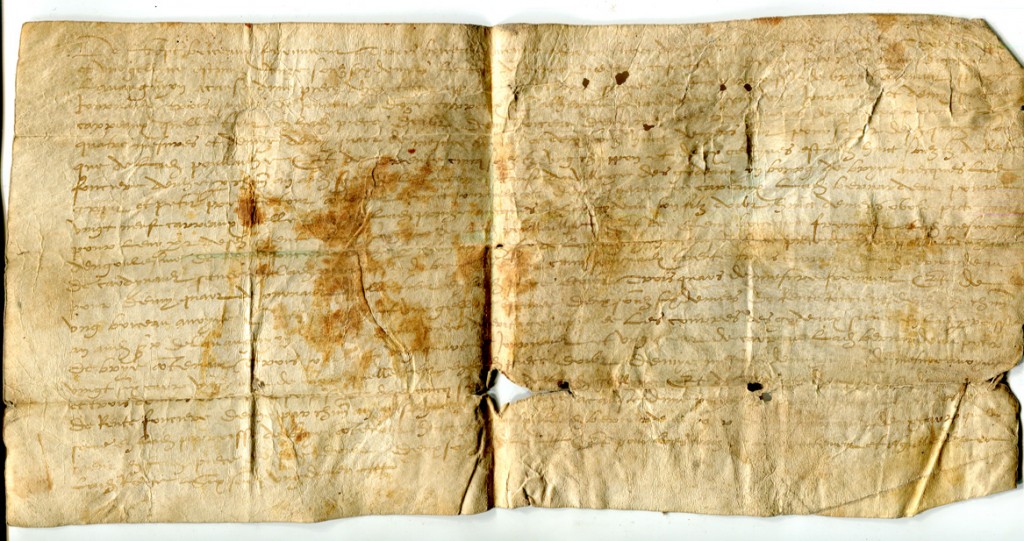

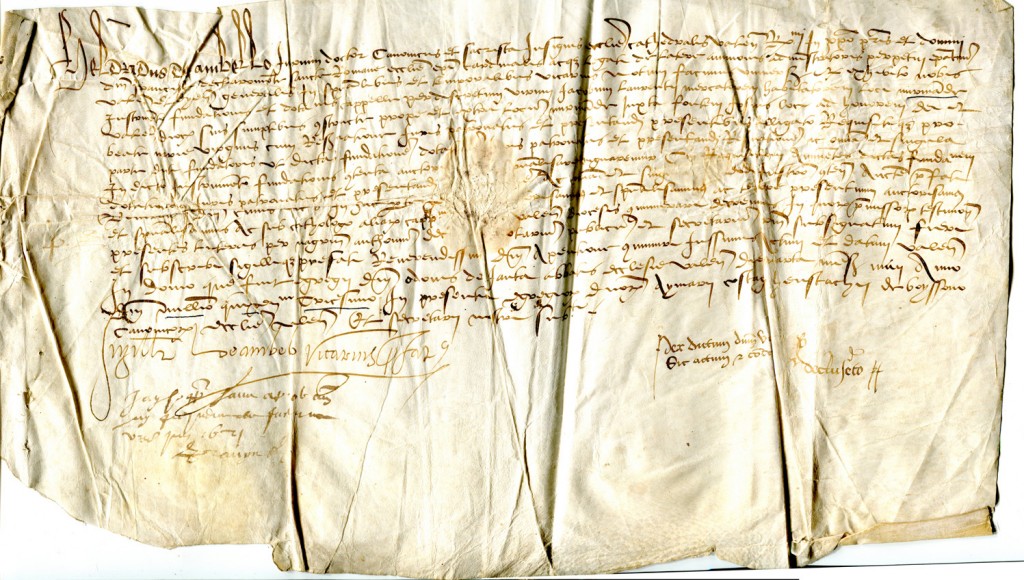

The guards comprise 2 reused Strips, cut to shape. The Strips are visible at each end of the volume, as a narrow Flap at the end of the text-block, formerly facing the boards and any pastedowns or endleaves pertaining to them. Wrapping around the fold of its gathering, each Strip re-emerges into view within the text-block as a narrower Stub in the gutter in the opening between pages at the other end of the gathering.

Each Strip carries writing in ink only on one side, which is the flesh side of the animal skin and the Face of the written material. The Dorse (hair side) is turned outward around the gathering.

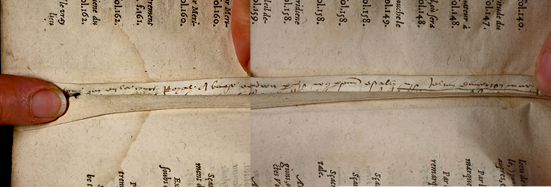

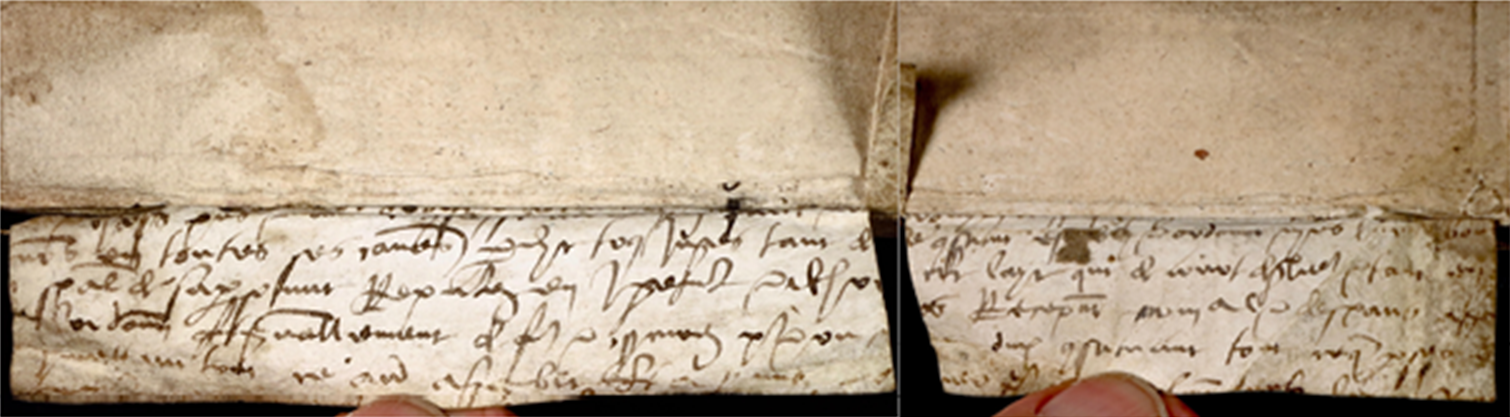

We call the guards Strips 1 at the back and 2 at the front, each with a Flap on the outside of the gathering and a Stub on the inside. Why number them that way, seemingly inverted? Spoiler Alert: Both Strips apparently come from a single manuscript or document, and the structure of their text indicates that Strip 1 would originally have preceded Strip 2.

The “outer” portion of each Strip, that is, the Flap, is slit about midway along into 2 sections. The slit corresponds to the middle row of sewing across the gatherings and its raised band.

Along the spine, it is possible to see the exposed outer edge of the guard at the front of the volume. Its color and texture contrasts with the paper of the gatherings otherwise. The guard extends not the full length of the gathering, but rather between its rows of kettle-stitchings at head and foot. At the end of the textblock, the guard sits alongside the 3 raised bands of stitchings spaced at even intervals along the spine. The slit midway along the guard which produced the 2 halves of the Flap on the outer side, but no division in the Stub on the inner side, is visible emerging alongside the raised middle band of stitching.

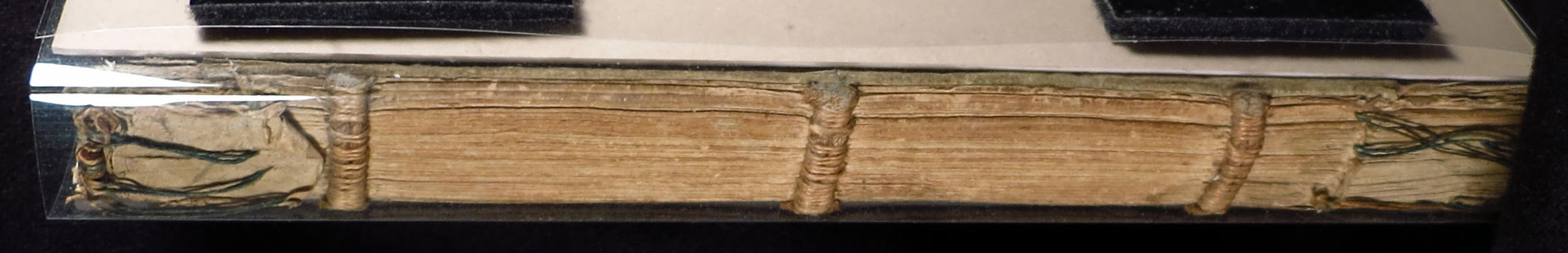

Smeltzer Collection, Henri de Suberville (1598), Spine View, with 3 Raised Bands flanked by a Row of Kettle-Stitching at either end.

Close up:

Smeltzer Collection, Henri de Suberville (1598), Spine: Front Midsection.

For each Strip, we show both front and back of each “outer” portion, or Flap, but only the visible Text Side of its Stub on the other side of the gathering.

Note that we view and number their portions taking the upright orientation of the script as the standard, not necessarily the position of the Strip as aligned with respect to the head or tail of the spine.

Strip 1 (at the Back of the Volume)

Flap 1a (Left-Hand Side)

Dorse (Hair side)

Smeltzer Collection, Henri de Suberville (1598), Vellum Supports, Strip 1 ‘Upper’ Dorse.

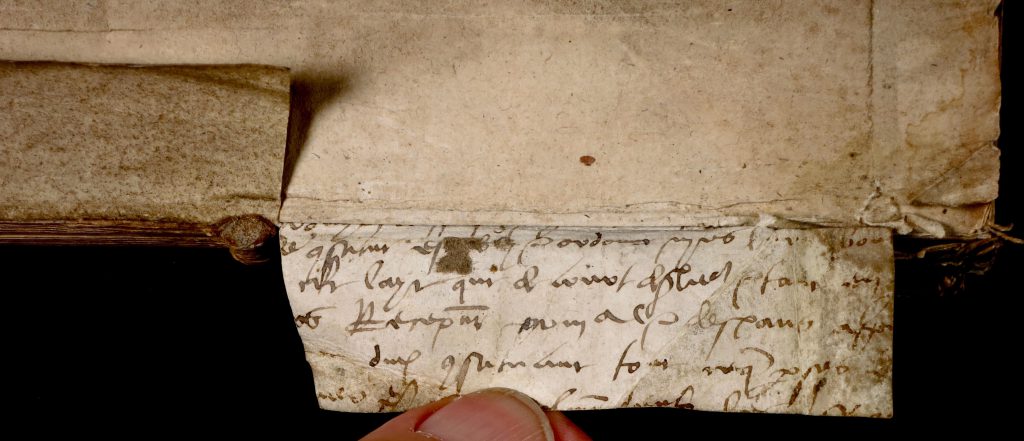

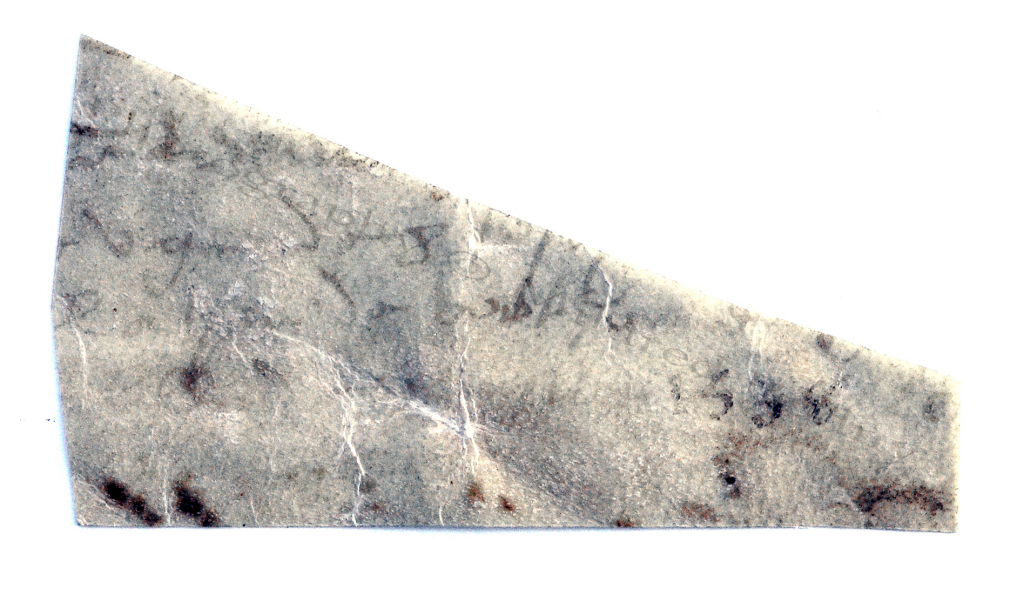

Face / Text Side (Flesh Side), with the text seen upright. Compare Ronald’s Figure 6 above in black-and-white.

Smeltzer Collection, Henri de Suberville (1598): Vellum Support 1, ‘Upper’, Face of Text.

Flap 1b (Right-Hand Side)

Dorse (Hair Side)

Smeltzer Collection, Henri de Suberville (1598), Vellum Supports, Strip 1 ‘Lower’ Dorse.

Face (Flesh Side), with the text seen upright

Smeltzer Collection, Henri de Suberville (1598), Vellum Supports, Strip 1 ‘Lower’ Face.

*****

Strip 2 (At the Front of the Volume)

Flap 2a (Left-Hand Side)

Dorse (Hair side)

Smeltzer Collection, Henri de Suberville (1598), Vellum Supports, Strip 2 ‘Upper’ Dorse.

Face (Flesh Side), with the text upright

Smeltzer Collection, Henri de Suberville (1598), Vellum Supports, Strip 2 ‘Upper’ Face.

Flap 2b (Right-Hand Side)

Dorse (Hair side)

Smeltzer Collection, Henri de Suberville (1598), Vellum Supports. Strip 2 ‘Lower’ Dorse.

Face (Flesh Side), with the text upright

Smeltzer Collection, Henri de Suberville (1598), Vellum Supports, Strip 2 ‘Lower’ Face.

On the Other Side of the Gathering

Stub 1 (Strip 1)

Left-Hand Side

Smeltzer Collection, Henri de Suberville (1598), Vellum Support Slip 1, Stub, Left (“Royal”).

Right-Hand Side

Smeltzer Collection, Henri de Suberville (1598), Vellum Support Slip 1, Stub, Right-Hand Side.

Stub 2 (Strip 2)

Left-Hand Side

Smeltzer Collection, Henri de Suberville (1598), Vellum Support Slip 2, Stub, Left.

Right-Hand Side

Smeltzer Collection, Henri de Suberville (1598), Vellum Support Slip 2, Stub, Right.

The Pieces ‘Rejoined’

We virtually reconstruct the visible portions of the Strips, which had to be photographed in sections. The fit in the reconstructed view is approximate, rather than exact, because, in photographing the elements within the still-sewn structure, the angles and distances would have varied between 1 half of an individual Strip and the other.

Strip 1 (Stub 1 + Flap 1)

Stub 1

Smeltzer Collection, Henri de Suberville (1598), Vellum Supports Slip 1, Inner Stub, Text ‘Rejoined’.

Flap 1

Smeltzer Collection, Henri de Suberville (1598), Vellum Support Slip 1, Outer Flap, Text ‘Rejoined’.

Strip 2 (Stub 2 + Flap 2)

Stub 2

Smeltzer Collection, Henri de Suberville (1598), Vellum Support Slip 2, Inner Stub, Text ‘Rejoined’.

Flap 2

Smeltzer Collection, Henri de Suberville (1598), Vellum Support Slip 2, Outer Flap, Text ‘Rejoined’.

The Location of the Fragments in the Original Document

and in the Current Binding

A set of diagrams represent the placement of the pieces of the vellum and the direction of its written text both on its document and in its pair of reused strips. With thanks to Leslie French for the renditions.

Reused Vellum Binding Fragments for Suberville (1598) in the Smeltzer Collection.

*****

The Script and Contents

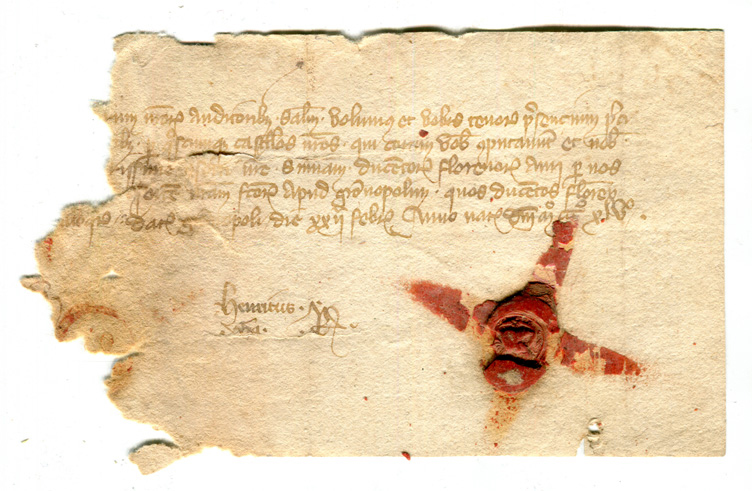

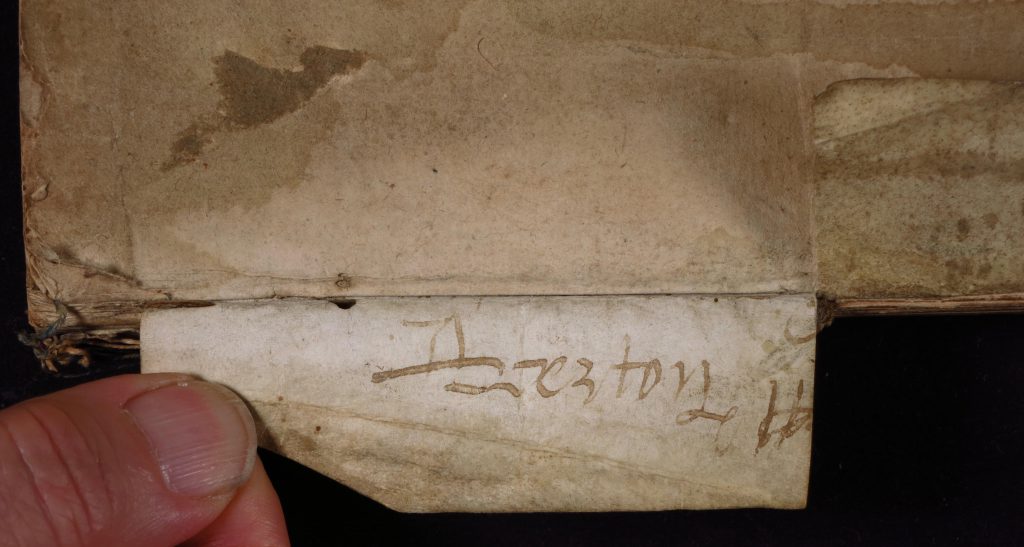

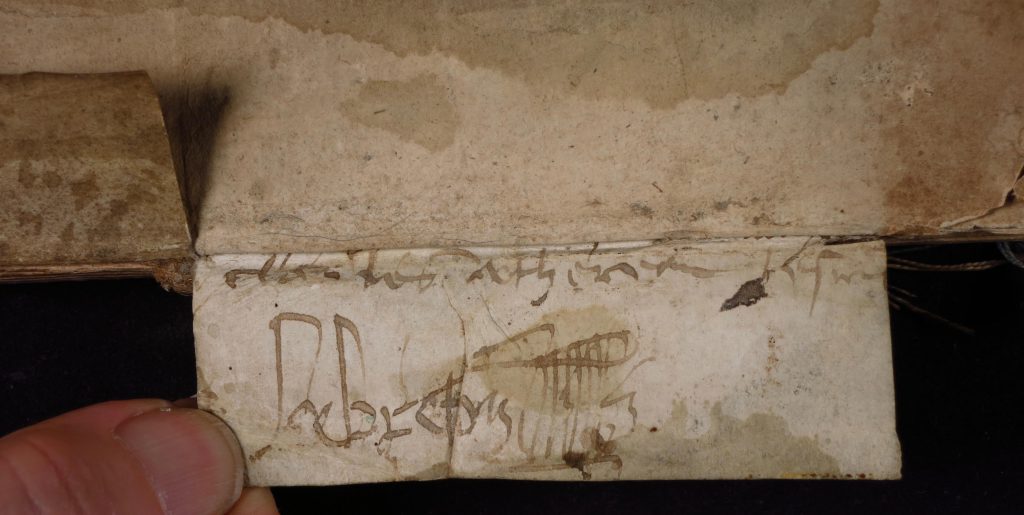

Parts of the text are visible. Some are legible.

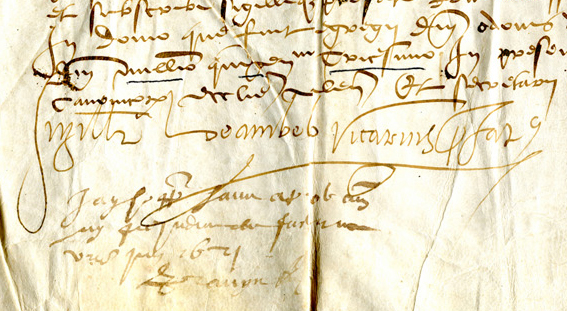

The Stubs carry parts of 1 or 2 long lines of cursive script. Flap 2 carries parts of 2 lines of script, comprising a line of text and a staggered line of names, plus flourishes. Remnants of at least 6 lines of script can be seen on the Flap of Strip 1. Near the beginning of its line ‘2’, there stand the words toutes ses . . . (“all his/her/its/their”). Following the ‘join’ of the parts of the Flap in line ‘3’, there are the word loys qui . . . (“all his/her/its/their”). The word Royal, with a distinctive capital R, appears clearly on Stub 1a. Similar Rs occur elsewhere as well. Made with a pen having a broader, scratchy nib and paler ink than the text above, the prominent signature(s), accompanied by flourishes (#), spread(s) across most of the Flap on Strip 2 ( . –reston # Lebr . . . #).

The 2 Strips manifestly derive from the same written text, which stood on the Face or recto of the vellum sheet (rather than sheets, presumably). Given the location of the signature(s) and the orientation of the lines of script, it is appropriate to reconstruct the original — at least in its visible surviving parts — with Strip 1 before, or indeed above, Strip 2. The text on each Stub precedes the text on its Flap, with an interval of script now hidden within the inside of the fold, amounting to 1 or more lines. Perhaps the script on the 2 Strips interlocks at the cutting line between them?

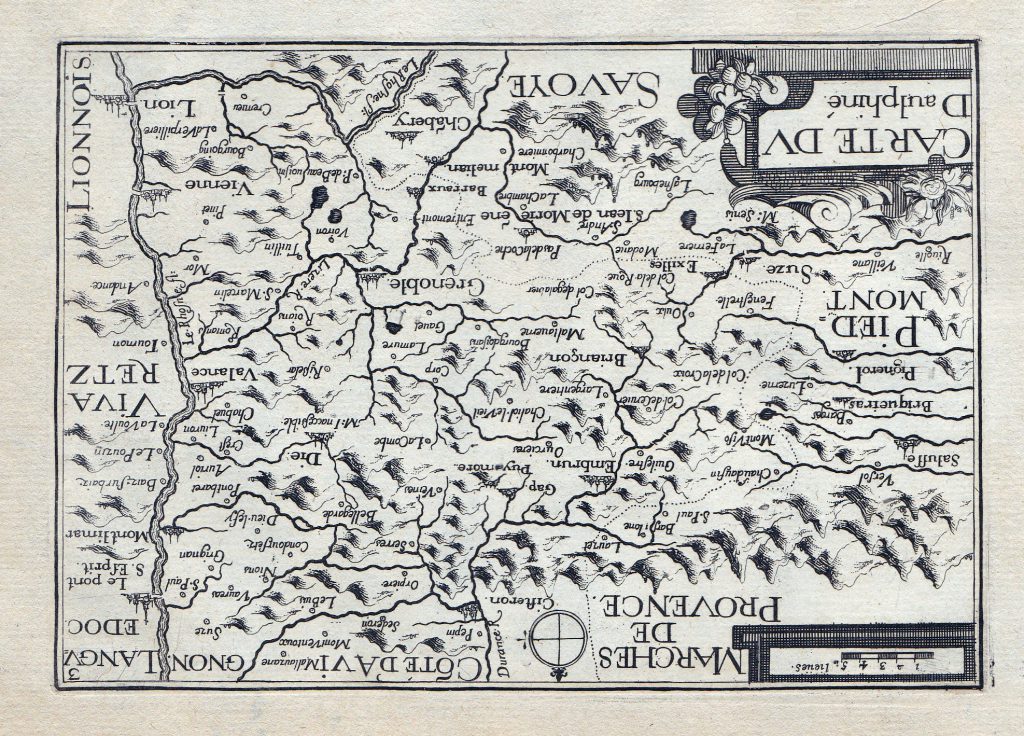

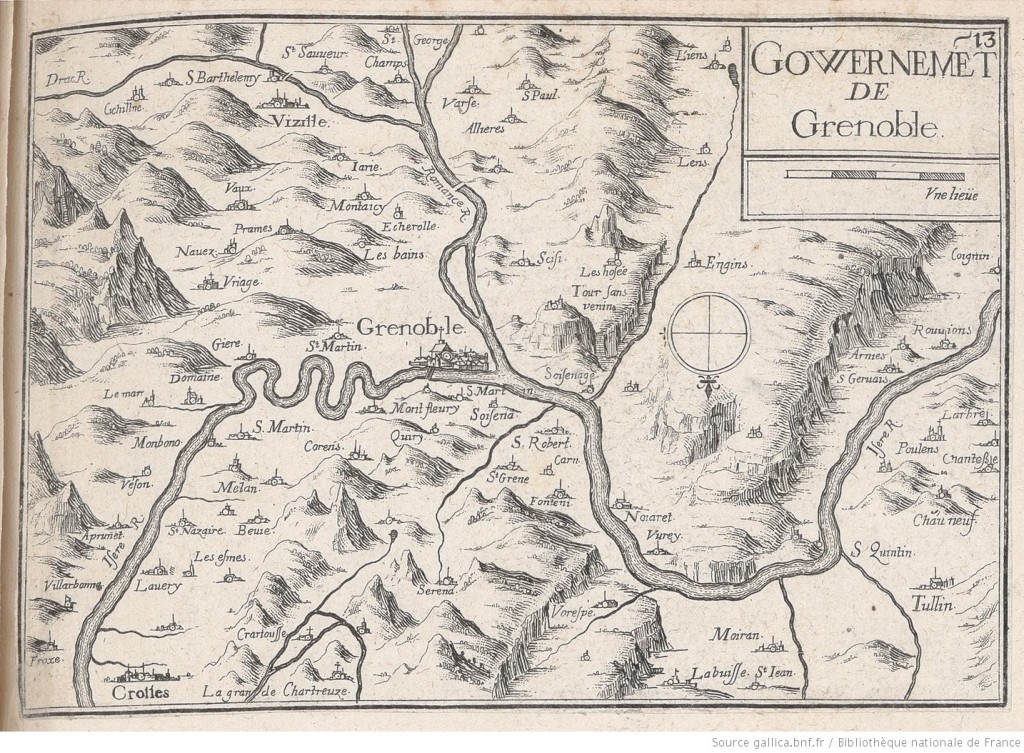

Written in ink in a “loose and sloppy hand” characteristic of the period (as described by our Associate, David Sorenson), the now-bipartite fragment comes from a French charter from about 1510–1520 or so. It was evidently a legal document of some sort, possibly a deed, lease, or other contract. Perhaps its signer(s) might be identified in other sources.

Our blog has already presented some French documentary materials on vellum with 16th-century script from other private collections.

- Say Cheese. Single-sheet document in Latin, circa 1530s, listing rents for plots of land, from Brie.

Private collection, Single-sheet document in Latin on vellum, circa 1530s, from Brie in France.

- Scrap of Information. Single-sheet document in Latin, circa 1530s, with a transaction at Vienne, in Isère.

Private Collection, Document in Latin from Vienne, circa 1530s.

Its Signatures:

Private Collection, Document in Latin from Vienne, France, circe 1530s

- Scrap of Information. Fragment of a leaf or document on vellum with the number/date 1538.

Recto of Scrap from a leaf or document, with the date 1538.

Image-enhancement reveals more of its features:

Recto of Scrap from a leaf or document, with the date 1538.

*****

We thank Ronald Smeltzer for permission to examine this volume and for information about its structure and context. We also thank David Sorenson for advice about the script and type of document from which came the reused vellum strips.

Do you recognize this reused document or its scribe? Can you read more of the text?

Do you know of other parts of the same document (or similar documents), say in the binding structures of other books — including this text by Henri de Suberville (1598) — printed by the same printer/producer, whether Adrien Périer or Jamet Mettayer, for example when the latter returned to set up shop in Paris?

Please let us know. You might reach us via Contact Us or our Facebook Page. Comments here are welcome too.

Watch for more discoveries. See the Contents List for this blog.

*****

Update: In January 2022, for the online series on “The Research Group Speaks”, Ronald Smeltzer gave a presentation on The Curious Printing History of La Science de L’Arpenteur.

Dupain de Montesson, La science de l’arpenteur (1766), Title Page Vignette. Ronald K. Smeltzer Collection. Photograph by Ronald K. Smeltzer, reproduced by permission.

*****