Full Court Preston

October 10, 2015 in Documents in Question, Manuscript Studies, Photographic Exhibition

Pair of 13th-Century Documents,

Pair of 13th-Century Documents,

Missing Their Seals,

from Preston

Plus a Competition, Prizes Included

[Posted on 10 October 2015, with updates. Also, now, see Preston Take 2.]

Next stop in our exploration of Manuscript and Document Studies. Still on the quest of Fragments and Their Contexts.

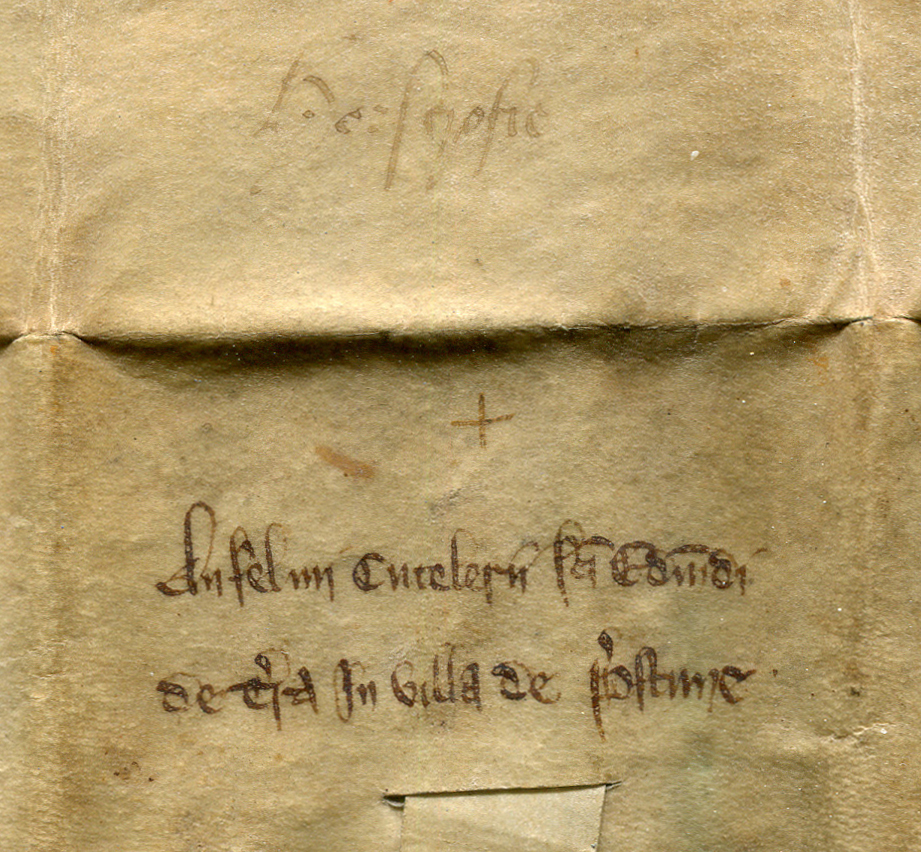

We turn now to a pair of documents in a private collection, reproduced by permission. They came for sale as part of a single batch, preserved together and sent forth together, apparently after centuries and generations with a common heritage. Their origin relates to Preston (now known as Preston Saint Mary), near Ipswich, in Suffolk in England.

A Self-Contained Entity

Documents get to tell their story unchained by other factors. They exist for what they are on the strengths of what they are and what they say They are intended to encapsulate the essence, and the essential components, of the transaction for which they form the record. And to stand up in court, if need be. Where they themselves do not survive in full, their testimony may lose some of its former ‘teeth’.

And here is where we, dedicated archaeologists, forensic specialists, and good-old-fashioned-manuscript-specialists not only love to work, but can come in handy. Case in point: Curiouser and Curiouser, regarding a curious (and then some) case in the same private collection.

But the isolated nature of documents, often now dislocated from their former contexts, requires a special focus. It’s sort of like charting an island in the middle of nowhere.

So What is That?

Well, good question. However they come down to us, we might wonder mightily that any of them survived at all.

And then we could examine what they retain, it could be by the skin of their teeth. Some of them, as here, have been stripped of their ‘best features’, namely their seals. That some of us still think that the scripts have great value is a position to maintain resoundingly. Do I digress? Not quite.

Here we showcase 2 documents which came from a shared location, separated across generations, both without their original seals. Some other reports on our website examine documents with, or without, their original seals.

Foster Home for Waifs & Strays

This pair now belongs to a private collection, reproduced and examined here by permission. The form in which they are shown here represents the form in which they were sold, apart from the added inventory number on their backs.

Now they have a ‘foster home’. Their owner purchased them as a single lot of 8 documents, gathered in a bag, in the 1980s in London, probably (according to recollection) in the Portobello Road. These 2 are the earliest of the lot.

Now they have a ‘foster home’. Their owner purchased them as a single lot of 8 documents, gathered in a bag, in the 1980s in London, probably (according to recollection) in the Portobello Road. These 2 are the earliest of the lot.

The pair has been set onto the world stripped ‘naked’ of fuller original forms of individual identification, including their original contexts. Shame!

Let’s be grateful, while gritting our teeth with frustration that not enough survives, that anything and everything, or, not quite everything, survives. I suggest that we turn to the skills of, shall we say, dentistry.

Dental Work

Call it pulling teeth. Sometimes the damaged materials appear to have been extracted forcibly from their original setting, for one or other reason. Sometimes the damage to the material itself results from further extraction, as with the excision of the seal from the rest of its document, presumably for the purpose of discarding that ‘skeleton’ in favor of the ‘prettier’ and presumably more valuable seal. Too bad that the damage leaves the document with only a stub of its former tag-or-tail-plus-seal, and its old protective bag reduced to an empty shell.

Press On

Remember, for the present purpose, we’re focusing on a place named Preston. The origin and meaning of that name derives from the Old English words prēost (“priest”) + tūn (“enclosure” or “settlement” — a term which evolved into the Middle English toun or town, provided that the settlement grew large enough and lasted long enough). Could mean almost anywhere with some form(s) of human habitation, providing that a priest was included.

Various places nowadays carry the name Preston, in England and elsewhere. The Preston in question here is the one situated near Ipswich (whose medieval forms included Gippeswic, Gyppewic, etc) in Suffolk, United Kingdom. Now this place is called Preston St Mary. Its present name emphasizes the ‘priest’ element and the patron saint of its church. Double Take.

The reasons why we cannot entertain the possibility that the Preston named in the 2 documents showcased here relates to some other Preston instead — as said, there survive many with that name — center upon their cited reference points to associated locations, Ipswich included. So, with these tidbits, clearing the field, we offer some hints for the hunt.

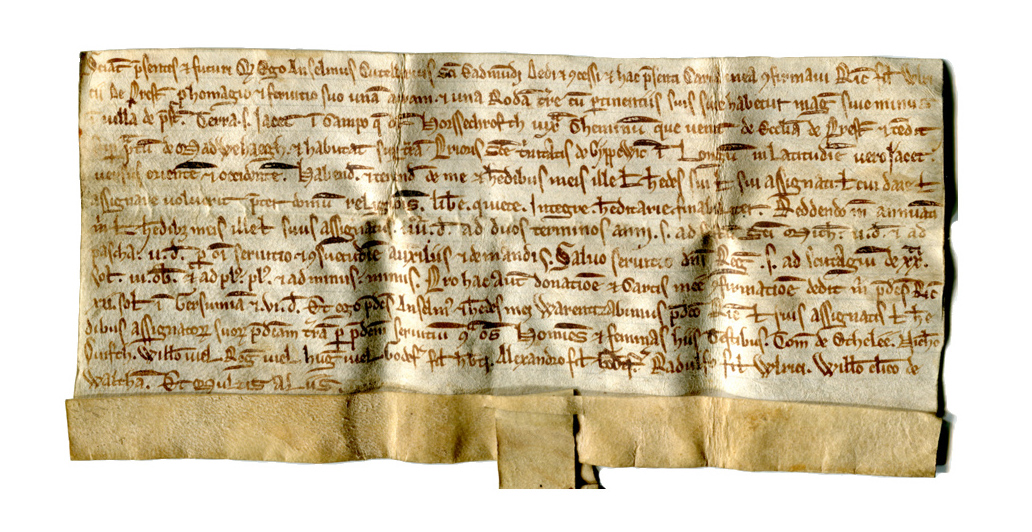

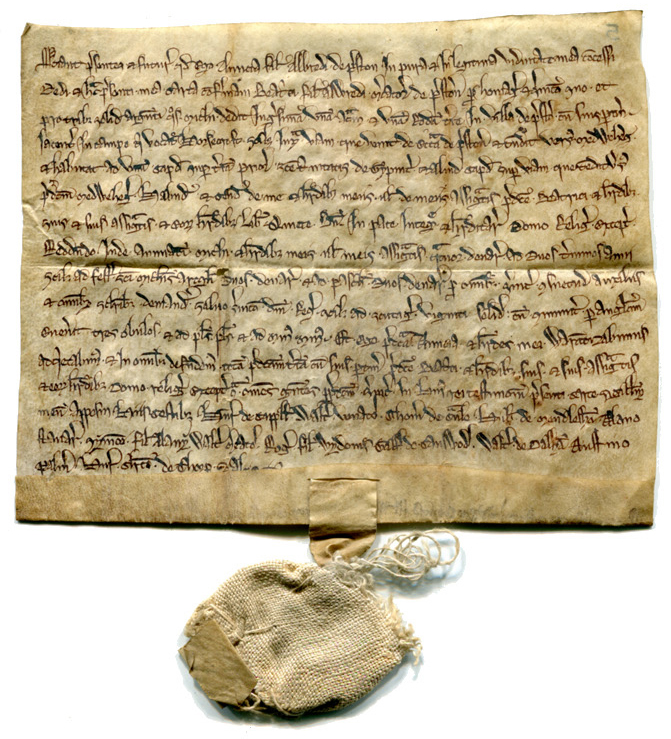

First Case: “Preston Charter 1”

This deed concerns a transaction of circa 1200 CE. As it says, it comprises the deed of a sale of a plot of land at Preston, near Ipswich. The document includes among its reference points both the ‘Church at Preston’, now the Church of Saint Mary the Virgin (an exterior view appears here), and the Priory of the Holy Trinity at Gyppewic, now known as Ipswich. (A newer Church of the Holy Trinity continues to function among the waterfront churches of Ipswich). Beautiful, clear script. Single, long column of 12 lines written by a professional. The text is entered upon the whitish flesh side of the animal skin, with the yellowed hair side turned to the recto. Rough edges, unevenly trimmed. The ensemble makes an empathetic statement.

Beautiful, clear script. Single, long column of 12 lines written by a professional. The text is entered upon the whitish flesh side of the animal skin, with the yellowed hair side turned to the recto. Rough edges, unevenly trimmed. The ensemble makes an empathetic statement.

The inward fold at the bottom of the sheet offers a nest for the lacing of the tab for the seal. The lacing passes through the roughly horizontal slits in the sheet, first facing front and then disappearing into the fold, to re-emerge at the bottom. Simple, given the hang of it.

Shame about the lost seal. A done deal.

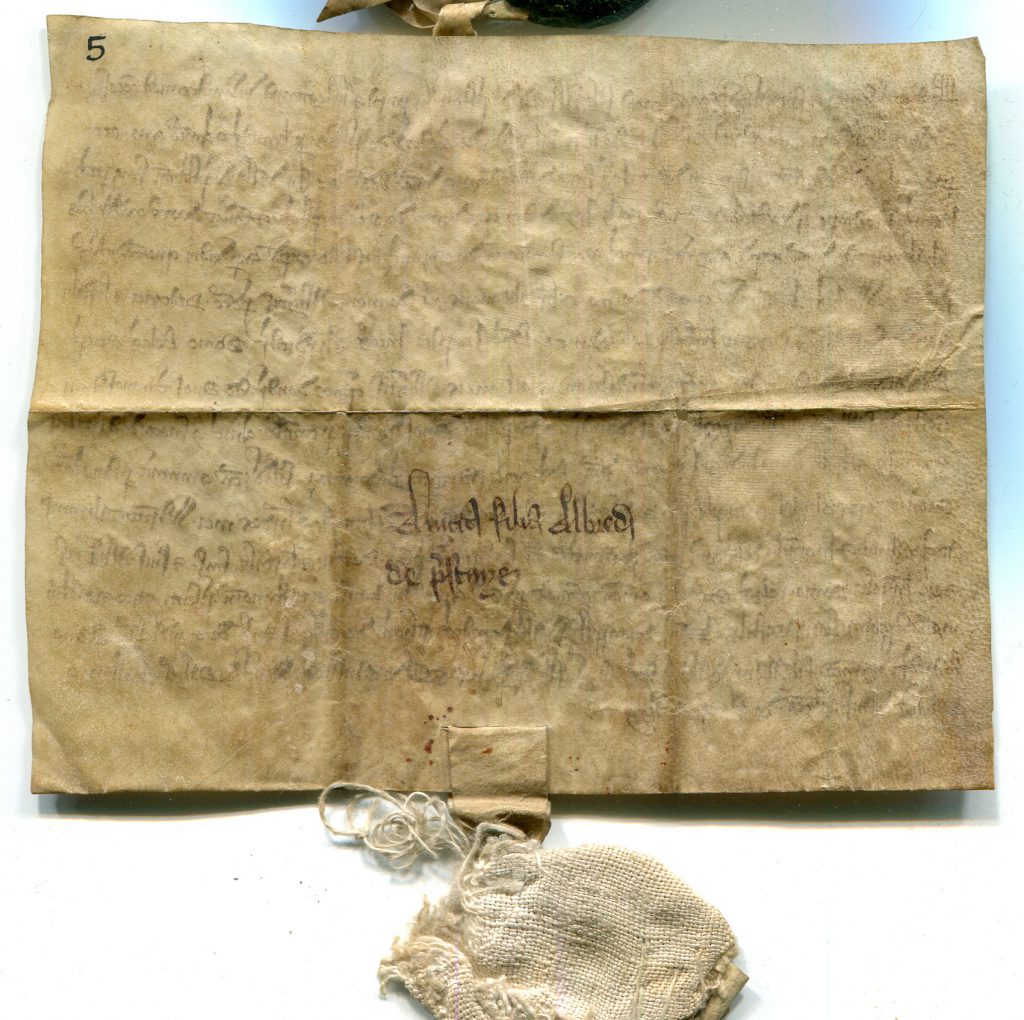

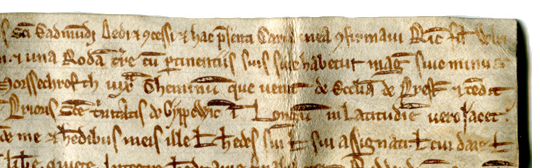

Next Case: “Preston Charter 2”

A document also relating to Preston. Mid 13th-century this time.

Now for a document on vellum of 16 long lines in a single column. Professional, too. Same type of fold-over, same sorts of unevenly-trimmed edges, same sort of tag. Except that now the simple plain-weave textile bag to cover and protect the original seal remains sort-of intact, with a cut edge at both top and bottom leaving an empty wrap. Not sure about the date of the bag. The seal is gone. Gone forever? Hope not.

We could figure the approximate original size of the seal (whose?) by the diameter of the bag. We can lament the severance and the loss (it may be) of the seal. Maybe we can discern where the seal has gone? Perhaps it survives on some other collection, and its existence may be recognized.

The inner fold encloses and mostly hides a line of text in the original hand. Visible within the fold, it stands to the right of the seal-tag; its show-through appears on the forward-folded dorse. The area to the left within the fold remains blank.

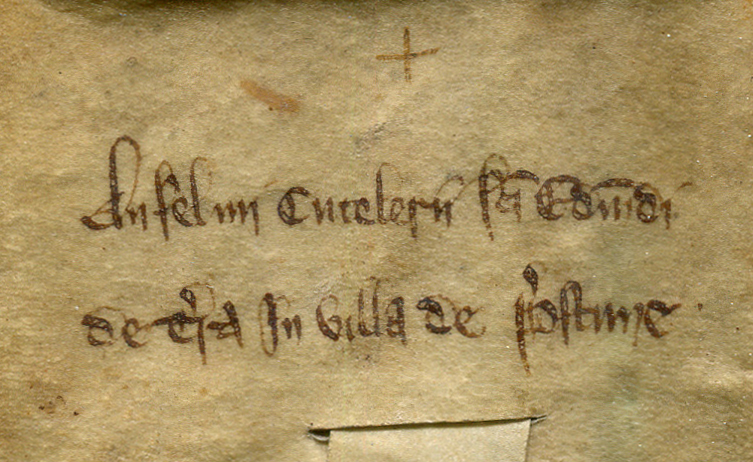

Back to Back

Each document has a mostly bare dorse, but for the modern inventory numbers 5 or 7 in black ink and the medieval docketing inscriptions of 2 lines in brown ink.

The pronounced fold lines and darkened stains demonstrate that each document formerly was stored folded in half lengthways, then folded across in thirds, to form a sub-rectangular packet. The lower center portion on the dorse, as the outermost fold of the packet, carries the identifying inscription above the seal tag.

“Preston Charter 2” = Charter 5

Preston Charter 5 Dorse.

“Preston Charter 1” = Charter 7

Preston Charter 7 Docketing.

Up Close

The docketing inscription in brown ink, surmounted by a simple cross in lighter brown ink.

Back to Now

I offer a book prize to the first person correctly to transcribe the texts of these documents and translate them into English.

(This is not a trick question. I haven’t had the time to do it, and I welcome help.)

Also, I offer a book prize to the first person to identify a surviving version of the seal for either document. That is, there might survive, somewhere, the original seal for one or other of them, or another impression, say on some other document, of the same authenticator’s seal. Such identifications are known to happen, although not as frequently as we might wish.

Remember, this prize — no, these prizes — are available to the correct responders.

- First Accurate Transcription for the Latin texts of Documents 1 and 2 (front and back) and their Translation into English

- Identification of the Current Location of the Lost Seal of Document 1, of Another Surviving Impression of the Same Seal, and/or of the Original Seal Matrix from which this Former Seal was Formed

- Similar Identification of the Lost Seal of Document 2

Fun Stuff, Bonus Included

For Real. First Time Ever that the Research Group on Manuscript Evidence has offered Book Prizes for a Competition.

Fun, huh?

The Books:

1 Book per category of Competition (1, 2, 3 above):

- Reginald Lennard, Rural England, 1086–1135: A Study of Social and Agrarian Conditions (1959, in special edition for Sandpiper Books, 1997), in hardback with dustjacket

- Abigail Wheatley, The Idea of the Castle in Medieval England (2004), in hardback with dustjacket

- Medieval England, 1000–1500: A Reader, edited by Emilie Amt (2008), in paperback

You can contact us via Contact Us or our Facebook Page. Comments here are welcome too. Please send your entries.

Winning entries will be published here.

In Favor of a Beautiful Smile

We look forward to your suggestions. Have fun!

*****

We thank the owner of the documents for permission to reproduce the images and to invite further research. Look forward to more discoveries.

[Update: Now see Preston Take 2. We have a Winner!]

*****

A fascinating thread has begun to unroll, with information about the surviving cases of seal pouches on medieval charters.

https://twitter.com/erik_kwakkel/status/727618561888407552/photo/1

Enjoy!

I have read your blog its really good and awesome. I want to ask which company can translate my Russian Language Documents?