Preston Take 2

April 3, 2020 in Manuscript Studies, Uncategorized

Revisiting a Set of 13th-Documents

in Latin from Preston in Suffolk

With a Winning Competition

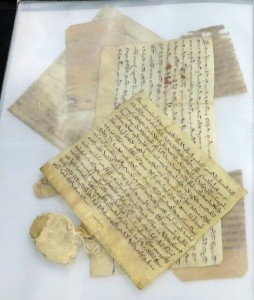

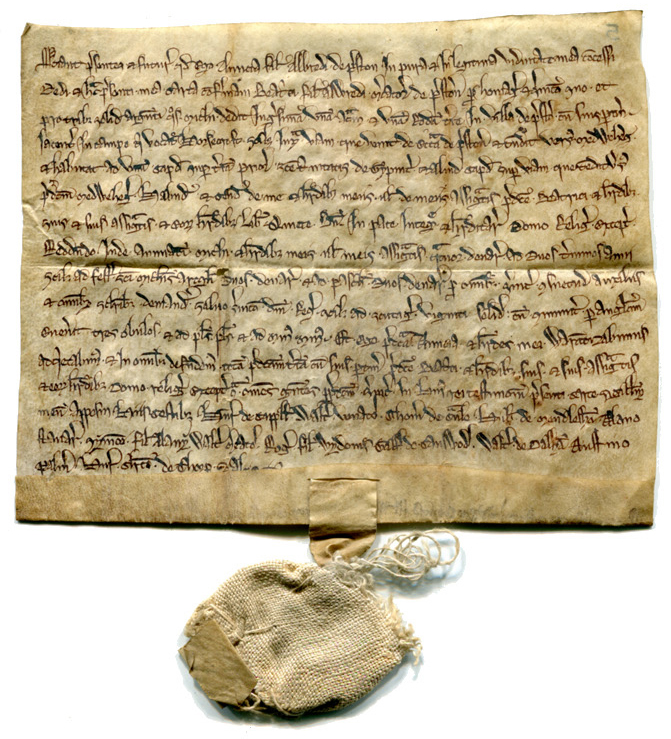

In our earlier blogpost on this subject, Full Court Preston, we showcased 2 single-sheet documents which came from a shared location, from dates there separated across generations, and with or without their original seals. We called them Preston Charters 1 and 2, now preserved in a private collection. Charter 2 lies at the top of the pile in the image here at the left.

Now, having had the opportunity to examine the full set of medieval charters from Preston which came as a group into that collection, we can call these two by their present owner’s numbering system (in these cases, Preston Charters 5 and 7), as we also announce the winner of our competition to transcribe and translate one or other, or both, of this selected pair.

Other reports on our website examine single-sheet medieval and later documents with, or without, their original seals. These reports appear

Document from Grenoble dated 22 February 1345 (Old Style), with wax seal.

1) In our blog on Manuscript Studies (see its Contents List):

2) In The Illustrated Handlist, Part II. “Documents on Vellum”

3) In Starter Kit, giving a brief introduction to a group of 14 medieval Seal Matrices (mostly, it appears, from England)

The Preston set came up for sale in London some years ago, apparently as a single batch, preserved together and sent forth together, after centuries and generations with a common heritage. Their origin relates to Preston (now known as Preston St Mary), near Ipswich, in Suffolk in England.

Now we revisit them, with a view of the set in full — insofar as it survives as a group of documents, plus some of their wax seals and a now-empty pouch for a seal. We announce the winner of our competition to transcribe and translate the first 2 documents, as first introduced in our blog, with observations about their specific characteristics. Other posts will report on other documents in the set, taking them pair by pair.

Foster Home

The pair already showcased (Full Court Preston) now belongs to a private collection, reproduced and examined here by permission. Their owner purchased them in the 1980s in London, probably (according to his recollection) in the Portobello Road, location of markets and shops of many kinds. These 2 are the earliest of that lot.

The pair already showcased (Full Court Preston) now belongs to a private collection, reproduced and examined here by permission. Their owner purchased them in the 1980s in London, probably (according to his recollection) in the Portobello Road, location of markets and shops of many kinds. These 2 are the earliest of that lot.

The group has been set onto the world from that marketplace stripped ‘naked’ of fuller original forms of individual identification, including their original larger contexts. Let’s be grateful, while gritting our teeth with frustration that not enough survives, that anything and everything, or, not quite everything, survives.

I suggest that we turn to the skills of, shall we say, dentistry. Call it pulling teeth, wherein the materials appear to have been extracted forcibly from their original setting, for one or other reason. Bringing to bear an array of techniques of examination, we might discern clues and cues with sufficient bite to chew on.

Press On

The documents collectively relate to one place named Preston. That they refer to that single place is clarified by their various reference points, or markers, within their boundary clauses defining the location and extent of the property which their documents transfer from one owner to another.

The origin and meaning of that name derives from the Old English words prēost (“priest”) + tūn (“enclosure” or “settlement”). Without further identifiers, the name itself could denote almost anywhere having some form(s) of human habitation — providing a priest was included as a distinguishing characteristic.

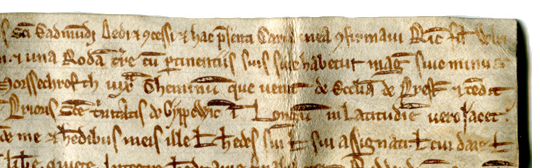

There survive many places in England which have the common Old English place-name Preston. Others may have changed their names from that one, while some with such a name may have disappeared from the record altogether. The identity and location of the ‘Preston’ named in ‘our’ documents center upon their cited reference points to associated locations, including Ipswich in Suffolk, United Kingdom. For example, the text of Charter 2/7 (see below) names both the Church at this Preston and the Priory of the Holy Trinity at Ipswich (‘Gyppewic’):

Naming the Church at Preston and the Holy Trinity at Ipswich (‘Gyppewic’) in a deed of sale of land at Preston, near Ipswich.

‘Our’ Preston is the one situated near this Ipswich, whose medieval forms included Gippeswic, Gyppewic, etc. Nowadays the place is called Preston St Mary, applying an identifier to distinguish it from other Prestons. Its present name emphasizes both the ‘priest’ element of the habitation and the patron saint of its church.

The Church of Saint Mary still stands in the village. The edifice dates from the 14th and 15th centuries, but it had to be rebuilt in 1868, after damage from a lightning strike in 1758.

Back to Front and Back Again

Each charter in the Preston group has a modern number, entered in black ink at the top left on the originally blank dorse, or back, of the sheet of vellum. Applied to the set by the present owner, the sequence extends from 5 to 13, relating to the full set as purchased and as positioned within a section of his collection dedicated to documents from England and gathered in a notebook. (Over time, he reports, the notebook for his “French” documents happens to have gathered more than this one.)

However, Charter 8 in this “Preston” series is now missing. The owner recalls that a photograph of it and the others might survive in microfilm in Cambridge, England, where it was photographed during the period between his purchase in London and his return to the United States after a period of study in Cambridge. Number 8 came to him in the group, but it went missing some years ago, after he gave a class with it; perhaps it will resurface.

A Fuller View of the Set

At first, I ‘met’ several of the Preston charters through photographs supplied by the owner, as part of the Research Group’s work of examining, researching, displaying, and publishing original manuscript and documentary materials, including some in his collection. In the several years since that ‘introduction’ and the publication of two of the charters in Full Court Preston, I have had the opportunity on 2 occasions to examine and to photograph the group as presently constituted.

Both occasions took place during visits to conferences, but in different years, in different parts of the country, and at different times of the year, respectively in the winter and in early summer. They allowed for viewing and photographing the items indoors under incandescent light and indoors under natural light. Both occasions show multiple aspects, while their conditions may emphasize or reveal different characteristics. Hence the bother to show you the different views.

Those direct experiences brought to light more evidence, which makes it desirable to revisit the group. At the same time, a winner had come forward for our competition, as proposed in Full Court Preston, concerning both showcased documents.

Group Portraits

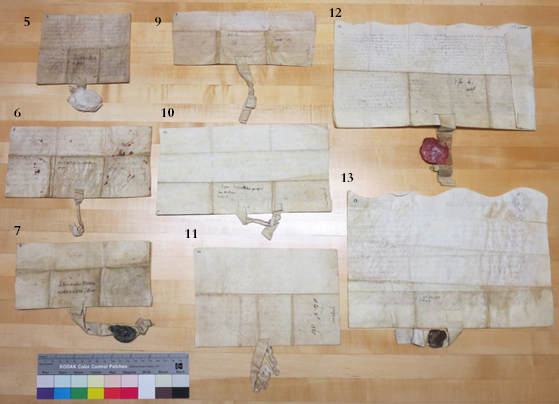

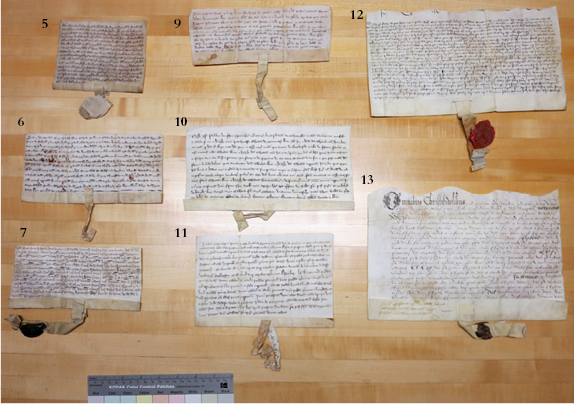

Meet the Group. Here the Preston Charters are displayed in their group, within single photographs showing first one side and then the other. The group comprises Numbers 5–7 and 9–13 in the modern numbering (without the lost or mislaid Charter 8).

Laid upon a wooden table top under a ceiling lamp, unfolded, and outspread, the group of documents first turns their backs (or dorse) to face us. This was the first chance that I had to meet them. Different from photographs. But I offer the photographs from that encounter, so that you might glimpse them also.

Here, as the owner set them out, they stand in 3 vertical rows. From left to right, and top to bottom, Row 1 has Charters 5–7, Row 2 has Charters 9–11, and Row 3 has Charters 12–13. Remember, no Charter 8 in view. For clarity, the item numbers which I have added to the photographs repeat their modern numbers within the group.

Preston Charters Dorses. Photograph Mildred Budny.

Preston Charters: Dorse with Guide. Photograph Mildred Budny.

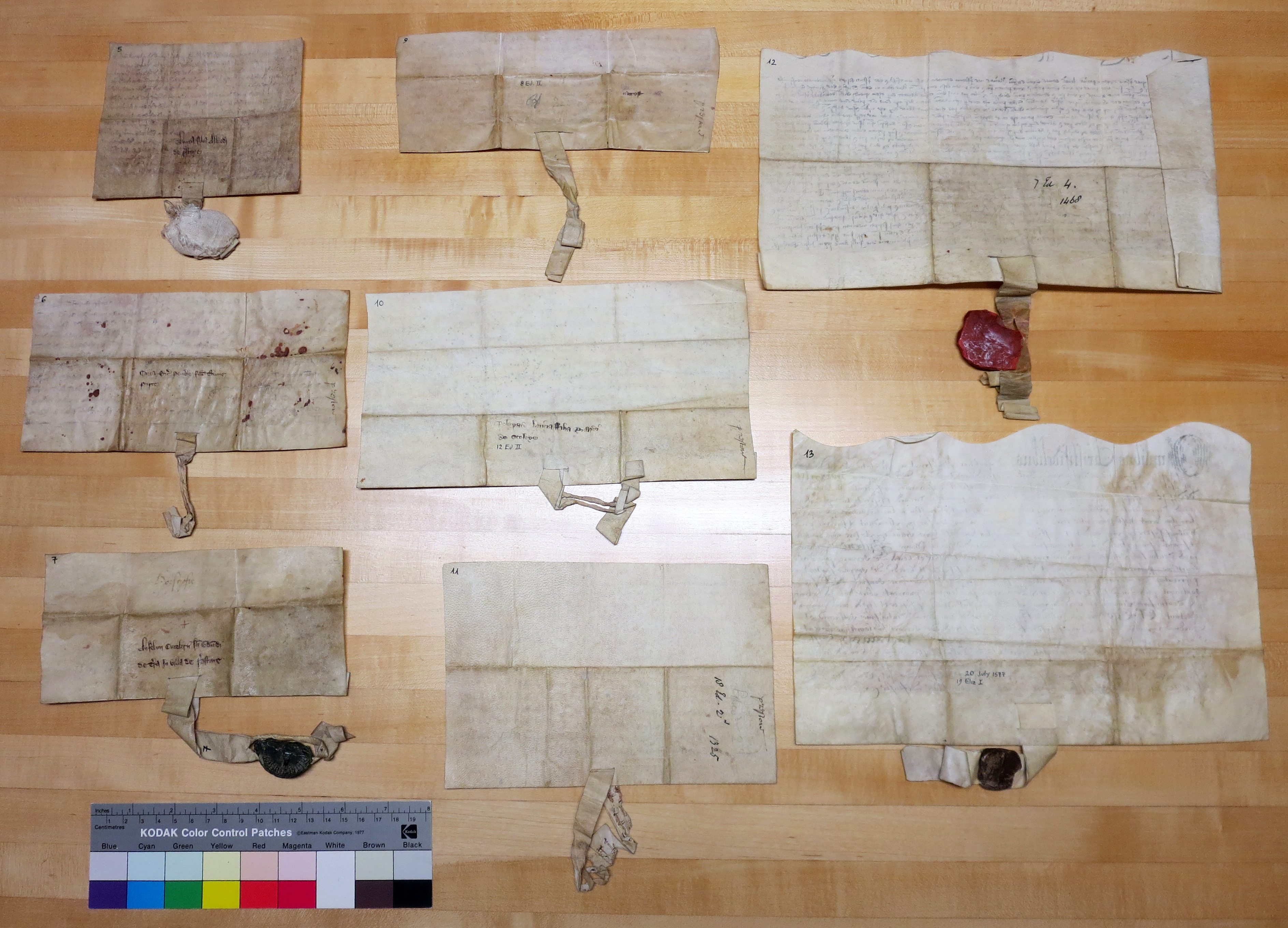

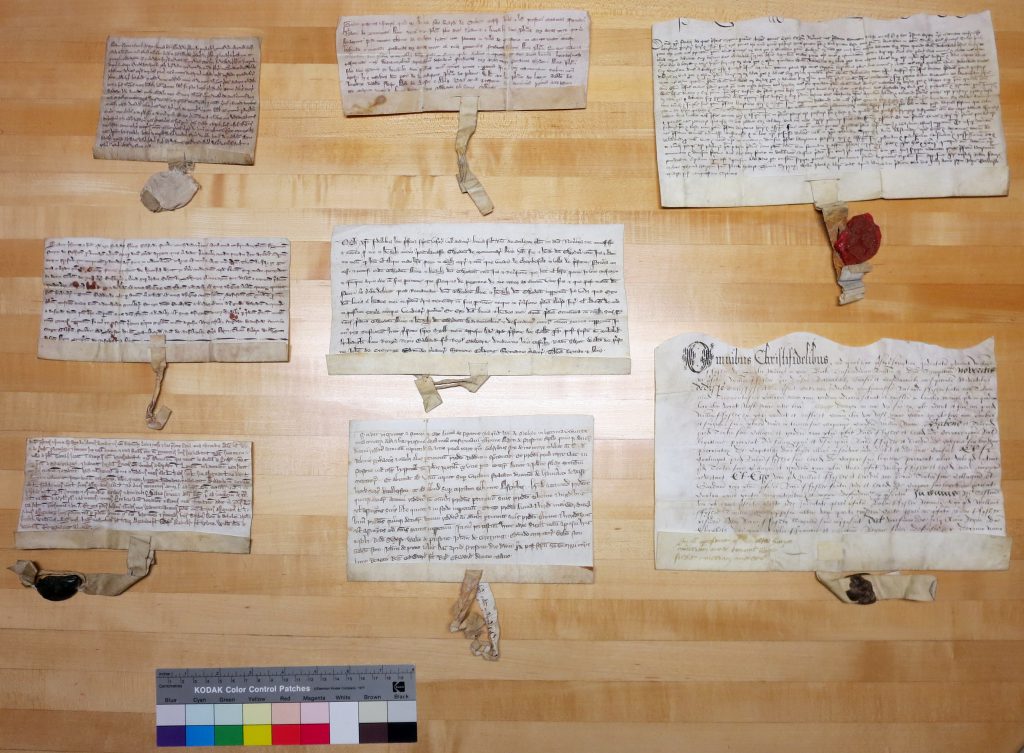

Next, they turn over to reveal their fronts, or faces.

Preston Charters Faces. Photograph Mildred Budny.

Private Collection, Group of 8 Preston Charters: Faces Forward. Photograph Mildred Budny.

Our earlier blogpost (Full Court Preston) referred to the pair which we showcased as Numbers 1 and 2, which carry the collector’s Numbers 5 and 7. In the Group Photos here, these two stand in Row 1, in its top and bottom positions.

Our Showcased Pair: Charters ‘1’ or 7 and ‘2’ or 5

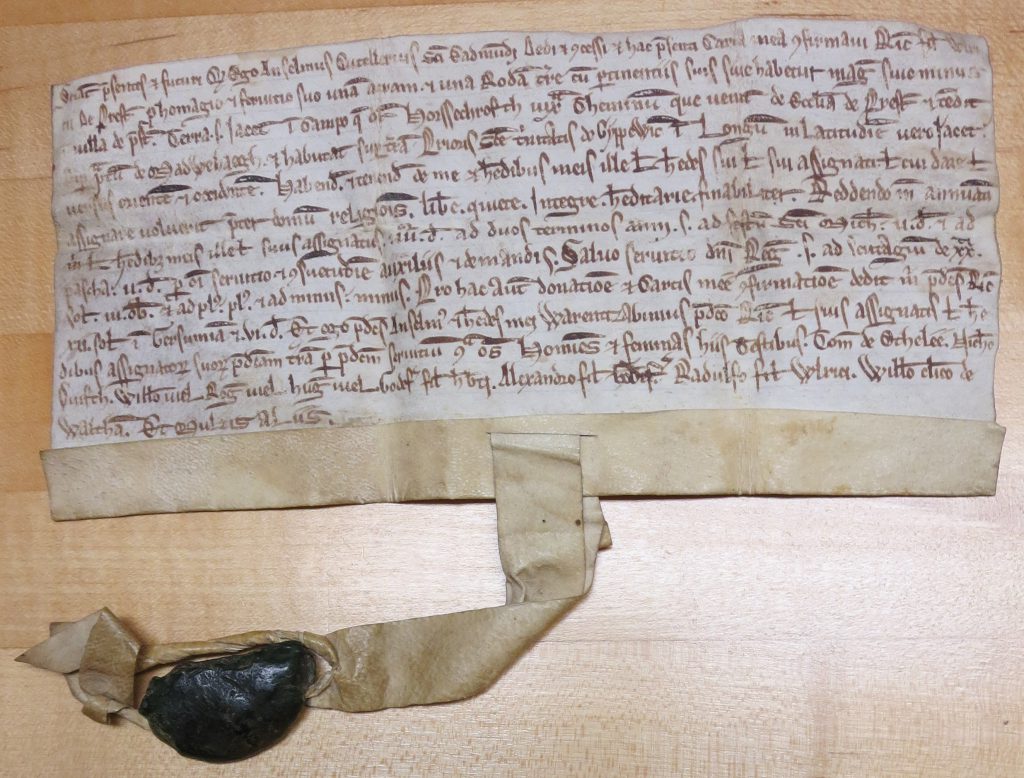

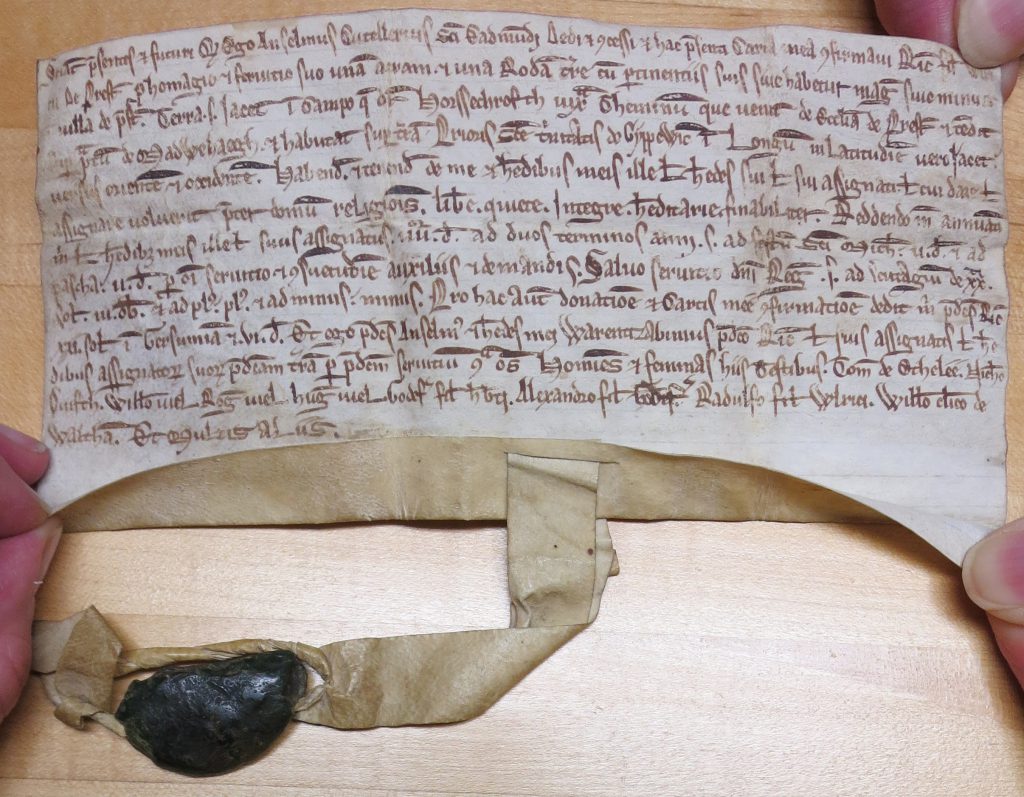

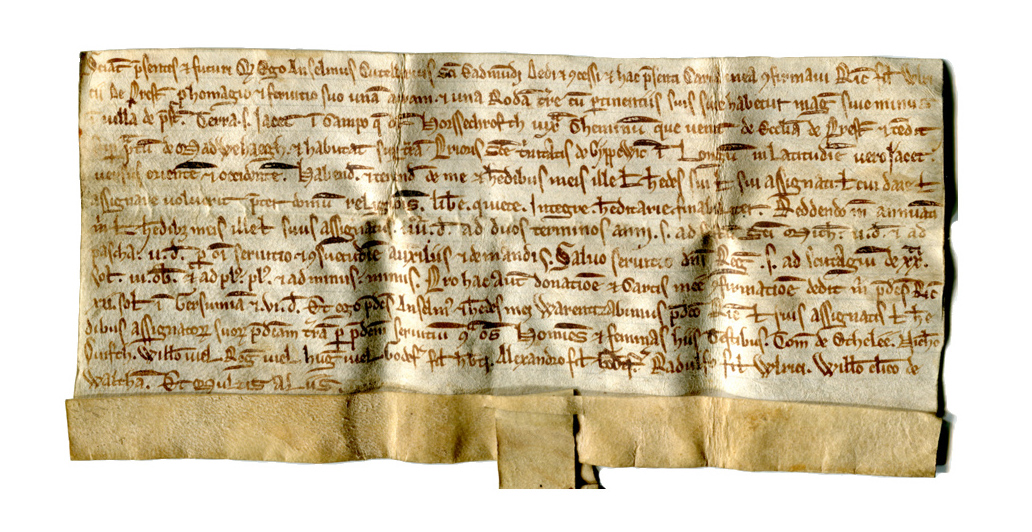

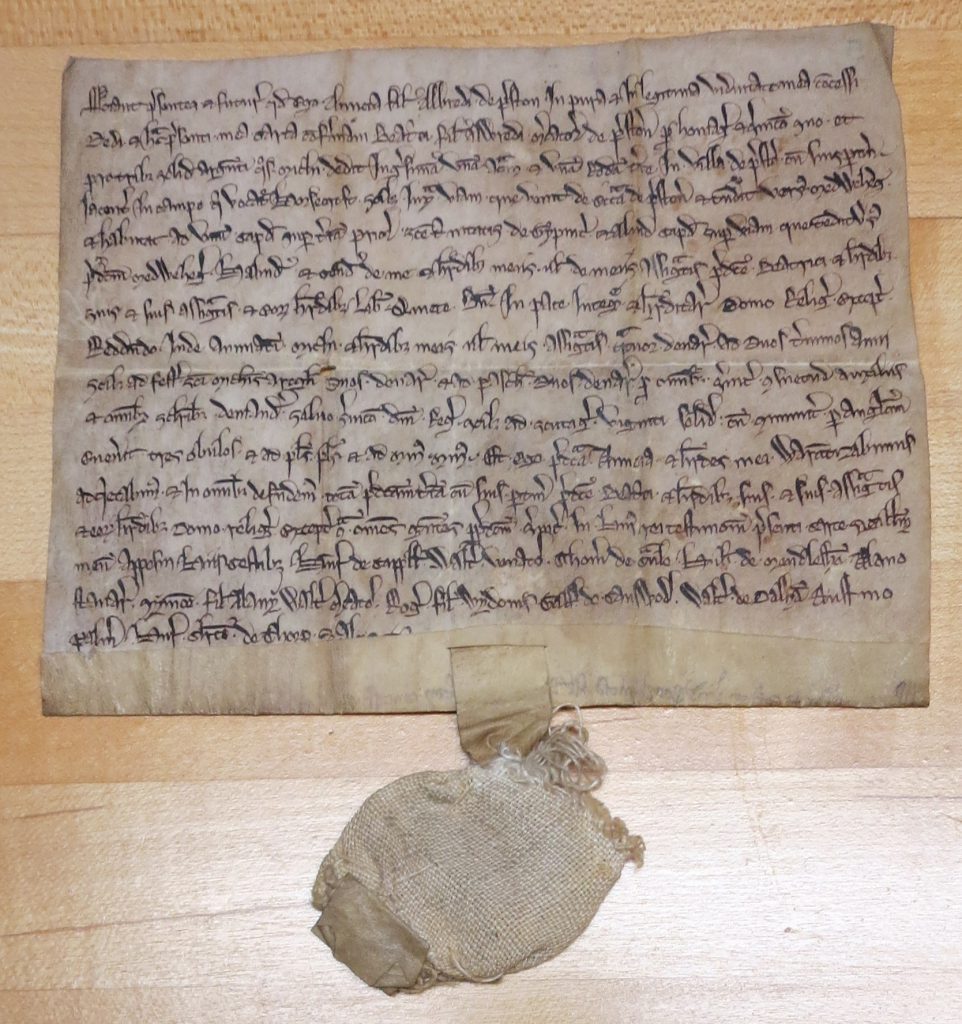

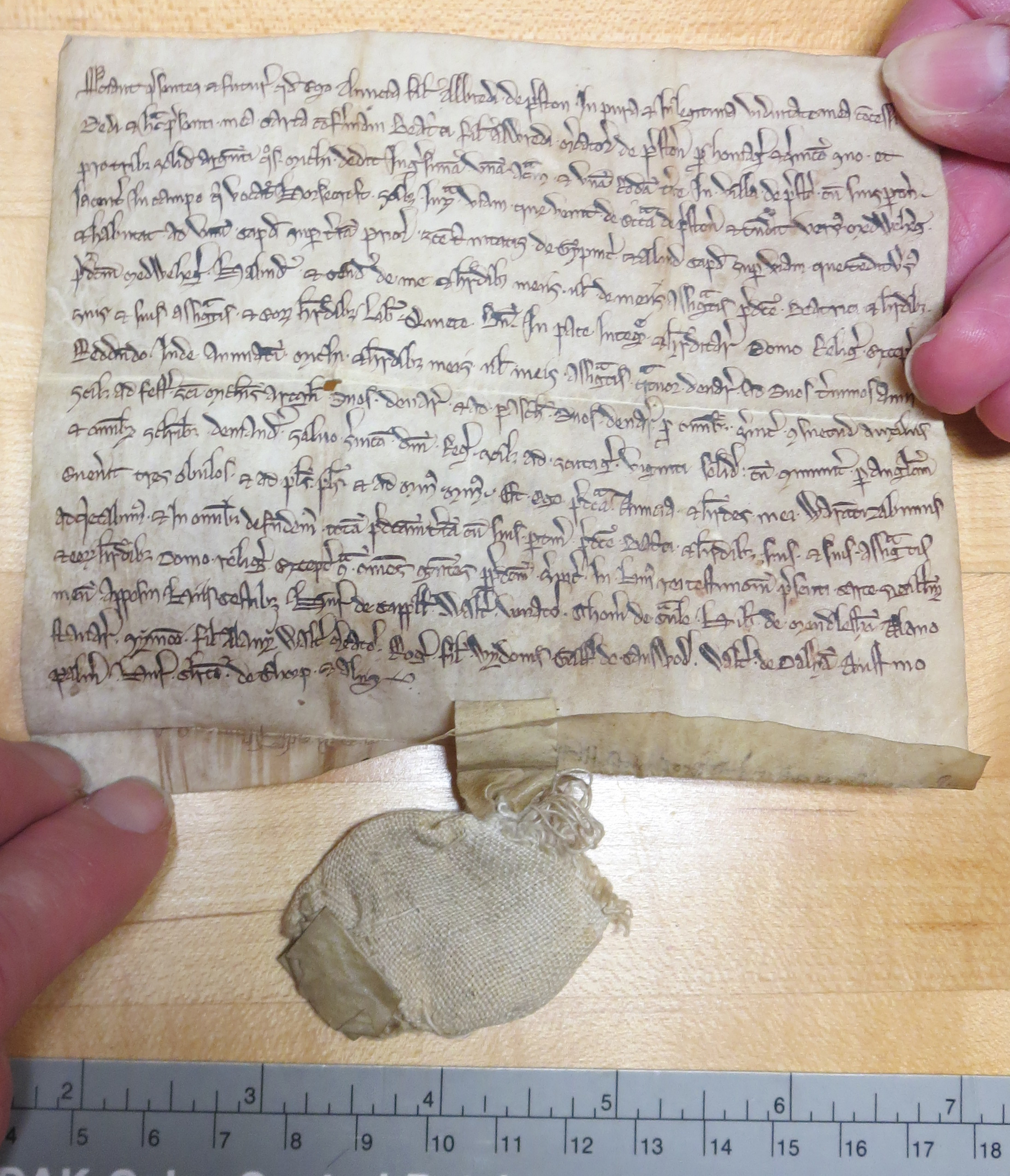

In each case, the single sheet of vellum, more-or-less evenly trimmed into a rectangle, was folded horizontally near its lower edge with a forward-facing portion at the baseline of the written document. For Charter ‘2’/5, the rectangular unit stands taller than wide, while for Charter ‘1’/7 (as for all the others in the group) it stands wider than tall.

At about midway across the bottom shelf-like fold, a separate, narrow strip of vellum laces through a pair of horizontal slits so as to form the attached tail-like tag for the seal. The lengths of the tags vary considerably, so as to place the seal close or far from the document.

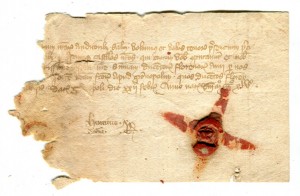

Each of these 2 documents has, or had, a seal affixed to the tag. One (Charter 7) retains about half its seal made of black or green wax. The other retains an old cloth pouch to protect its seal. The pouch is made of a plain-weave textile, apparently linen. The seal itself has disappeared, in a removal through the hole at one or other end of the pouch.

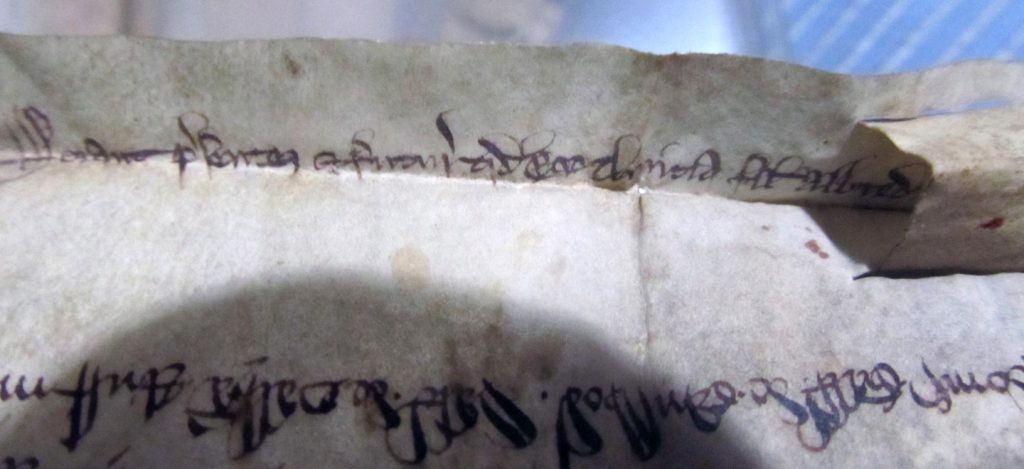

Their pronounced fold lines and darkened stains demonstrate that each completed document was folded in half lengthways, then folded across in thirds, to form block-like sections in a sub-rectangular packet, in which form it was stored at length. The lower center portion, or ‘front’, of the folded unit carries the medieval identifying, or docketing, inscription written in ink in 2 lines above the seal tag. In the block-like section above this one, as unfolded, each document carries an inscription in a different hand, in lighter brown ink, with a single word naming the place involved in the sale.

Each document, undated, records the vendor’s sale of a plot of land at Preston. One vendor was male, the other female. One buyer was male, the other female.

First Case: Charter Number ‘1’ (as we used to call it)

or Preston Charter ‘7’ (as the collector numbered it)

Deed issued by Anselm Cutler of Saint Edmund

for the Sale of Land at Horssecroft (or Horscroft)

to Richard, son of Ulrich of Preston

To judge by the style of script, this deed concerns a transaction of circa 1200 CE. It comprises the deed of a sale of a plot of land at Preston, near Ipswich. The document includes among its reference points in the boundary clause both the ‘Church at Preston’, now the Church of Saint Mary the Virgin (an exterior view appears here), and the Priory of the Holy Trinity at Gyppewic, now known as Ipswich.

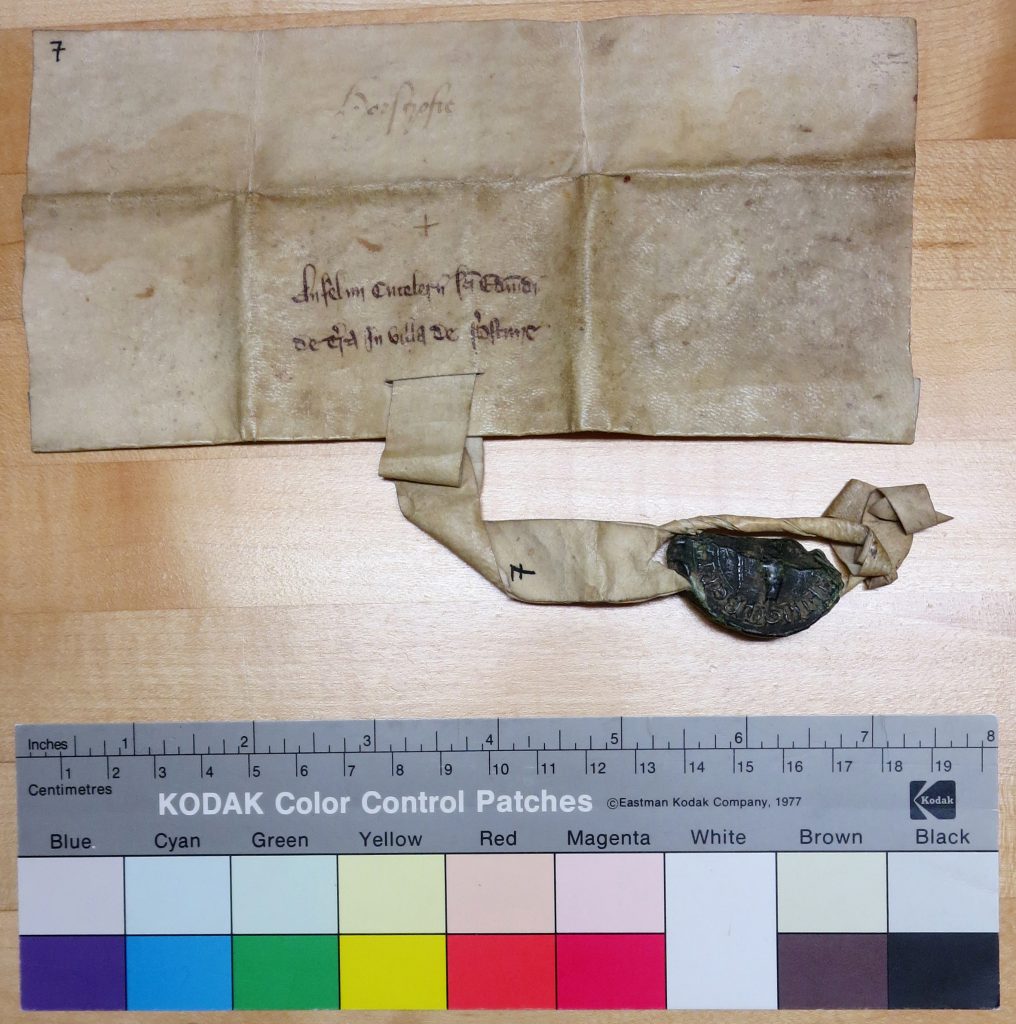

Dorse

Mostly blank, the dorse carries a series of inscriptions in ink, including the modern owner’s inventory number 7, which stands both at the top left and upon one side of the tag above the wax seal.

Preston Charter 7 Dorse. Photograph Mildred Budny.

The docketing inscription written in 2 lines above the tag names the grantor, the subject of the purchase (terra), and the location of that land.

Anselmi Cutelerii sancti Edmundi

de terra in villa de Prestone

[Deed] of Anselm Cutler of Saint Edmund

Concerning Land in the Vill of Preston

In medieval English usage, a Vill was “the basic rural land unit, roughly comparable to that of a parish, manor, village or tithing“.

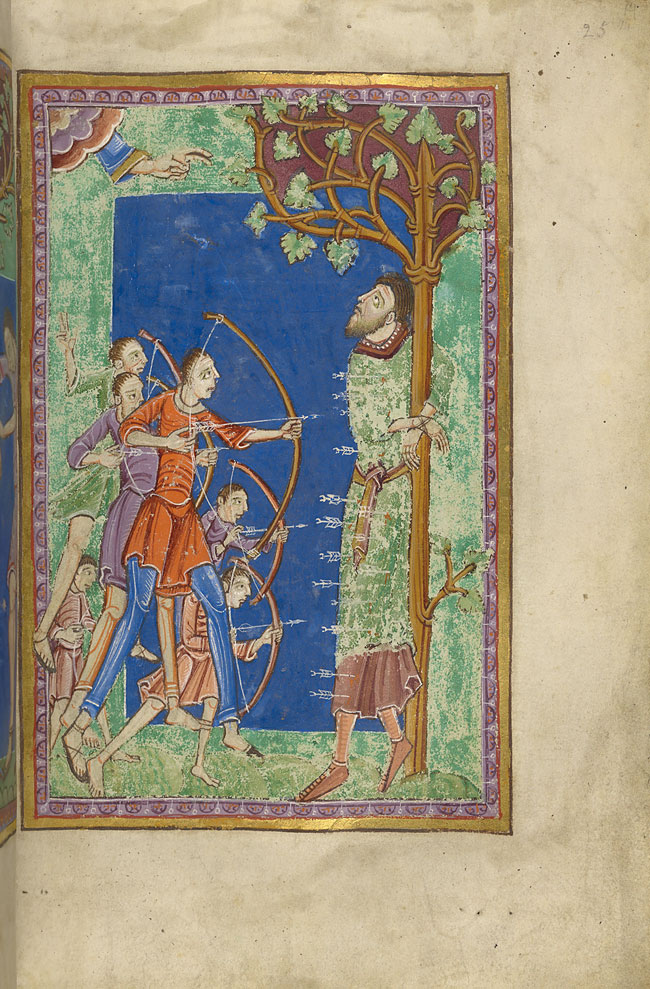

Presumably Anselm Cutler’s location “of Saint Edmund” designates Saint Edmundbury, now known as Bury Saint Edmund’s, in Suffolk — the location of the shrine of Saint Edmund the Martyr (841–869), King of East Anglia.

New York, Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.736 fol. 14r. Life and Martyrdom of Saint Edmund. Bury St Edmunds, circa 1130.

Hovering above that inscription, another in pale brown ink in a later hand presents the single word Horscroft, emulating, approximating, or varying the field-name Horssechrofth in the charter. The place Horscroft or Horscroft, Horningsheath, in Suffolk is cited in several 19th- and early 20th-century sources. Examples:

- Horscroft: Thomas Moule, The English Counties Delineated: Or, A Topographical Description of England (1837), page 277.

- Horscroft: Public Record Office, List of Early Chancery Proceedings, Bundle 32, page 326, item 64 (a sale of land there)

- Horscroft. : County of Suffolk: Its History as Disclosed by Existing Records …, edited by Walter Arthur Copinger, Volume III, page 214

- Horscroft, within Horningsheath: E. R. Kelly, Postoffice Directory of Norfolk & Suffolk, page 710

Face

Preston Charter 7 Face. Photograph Mildred Budny.

Fold (Partly Lifted), Pendant Tail or Tag, and Fragmentary Seal (Dorse)

Preston Charter 7 Face and Dorse of Seal. Photograph Mildred Budny.

Another View of the Text (As we first saw it in photographs and first published it)

The text is entered upon the whitish flesh side of the animal skin, with the yellowed hair side turned to the recto. The sheet has rough edges, unevenly trimmed. The text is laid out in a single, long column of 12 lines written by a professional. At the bottom of the sheet, the front-facing fold provides scope to nest the lacing of the tab to take the wax seal. The lacing passes through a set of roughly horizontal slits in the sheet, by entering the front of the fold and disappearing into it, to re-emerge at the bottom. Simple, once one has the hang of it.

The text is entered upon the whitish flesh side of the animal skin, with the yellowed hair side turned to the recto. The sheet has rough edges, unevenly trimmed. The text is laid out in a single, long column of 12 lines written by a professional. At the bottom of the sheet, the front-facing fold provides scope to nest the lacing of the tab to take the wax seal. The lacing passes through a set of roughly horizontal slits in the sheet, by entering the front of the fold and disappearing into it, to re-emerge at the bottom. Simple, once one has the hang of it.

Above the seal, the tag is slit vertically into 2 tails. One of them holds the seal. The other twists around it to wrap around the first below its span, as a form of lock or closure.

The Seal

The seal came into our view only after our first blogpost on the pair of Preston charters (Full Court Preston), when it became possible to see the objects as a group in person. (Photos above.)

About 1/2 of the rounded, probably circular, seal survives. It retains part of both the legend (text) around the rim and the device (image) within the central field. The dorse of the seal forms a lump-like mound. The face of the seal presents a partial inscription in Latin in continuous Lombard Capitals, with no word division, leading to the personal name GILBERTVS in some form, presumably the nominative Gilbertus or genitive Gilberti (“Gilbert’s”). The preceding letters belong, apparently, to a genitive name ending in –i.

[.]W[G? or H?]IGILBERT[..].

The remnant of the inscription includes neither the opening nor closure of the legend, such as a customary cross or asterisk, while the accompanying image implies that this view of the seal is upside down.

Preston Charter 7 Seal Face with the name Gilbert.

Turned the other way, the image may be seen to depict the lower 2/3 or 3/4 of an upright human figure wearing an ankle-length tunic and perhaps having outstretched or upraised arms. Elements of vertical framework stand to either side, perhaps as an architectural arcade?

Preston Charter 7 Seal Face with the name Gilbertus.

Transcription, Translation, and Notes

We owe this section to the winner of our competition (see the announcement of the competition in Full Court Preston, and below). We thank and congratulate him.

William H. Campbell

Department of History

University of Pittsburgh at Greensburg

1. Transcription of the Text

(Keeping the line divisions of the original, Adding line numbers, and Expanding the abbreviations,

with some Notes)

[Line 1]

Sciant presentes et futuri Quod Ego Anselmus Cutellarius Sancti Edmundi Dedi et concessi et hac presenta Carta mea confirmavi Ricardo filio Wlri[-]

cii De Preston pro homagio et servitio suo unam acram et una [sic for unam] Rodam terre cum pertinentiis suis sive habetur magis sive minus

in villa de preston’. Terra scilicet iacet in campo quem dicitur Horssechrofth iuxta Theminum que venit de Ecclesia de Preston’ et tendit

super pratum de Madwehaegh. et habutat[1] super terram Prioris Sancte trinitatis de Gyppewic’ in Longum in Latitudine vero iacet

[Line 5]

versus orientem et occidentem. Habenda et tenenda de me et heredibus meis ille et heredes sui et sui assignati. Et cui dare et

assignare voluerit praeter domum religionis. libere. quiete. Integre. hereditarie. finabiliter. Reddendo inde annuatim

mihi et heredibus meis ille et suus assignatus iiiior denarios ad duos terminos anni scilicet ad festum Sancti Michaeli ii denarios et ad

pascha ii denarios per omni servicio et consuetudine auxiliis et demand[abil]is. Salvo servicio domini Regis scilicet ad scutagium de xxti

solidi iii ob’ et ad plus plus et ad minus minus.[2] Pro hac autem donationem et Cartis mee confirmationem dedit mihi predictus Ricardus

[Line 10]

xii solidi in Gersumiam[3] et vi denarii. Et ego predictus Anselmus et heredes mei Warentizabimus predicto Ricardo et suis assignatis et here[-]

dibus assignatorum suorum predictam terram per predictam servitiam contra omnes Homines et feminas hiis testibus. T[h]om[as] de Ochelee.[4] Nicho[las]

?uitsth. Willelmo mel.[5] Rogero mel. Hugoni mel. Godefrido filio herberti. Alexandro filio godefridi. Radulfo filio Wlrici. Willelmo clerico[6] de Waltham’. Et multis aliis.

Translation (Highlighting Personal and Place Names in Bold)

Let all present and future persons know that I, Anselm Cutler of St Edmund, have given and conceded and by this present charter confirmed to Richard son of Ulrich of Preston, for his homage and service, one acre and one rod of land, together with its appurtenances, both great and small, in the vill of Preston. Namely, the land lying in the field that is called Horssechroft next to Theminum, which comes from the church of Preston and extends up to the meadow of Madwehaegh, and abuts upon[1] the land of the Prior of Holy Trinity, Ipswich, in length and breadth, that is, lying across east and west; for him [Richard] and his heirs and his assigns to have and to hold from me and my heirs, and to whomever he shall wish to assign and give it (excluding a religious house), freely, quietly, entirely, hereditably, and forever; he and his assigns rendering annually to me and to my heirs four pence at the two terms of the year, namely two pence at Michaelmas and two pence at Easter, for all service and custom, aids and things that may be demanded, except service to the lord King, namely, a scutage of 20 shillings three ha’pennies (more if more, less if less).[2] For this grant and charter the foresaid Richard has given to me 12 shillings in fine[3] and six pence. And I, the foresaid Anselm, and my heirs, guarantee to the foresaid Richard and his assigns and to the heirs of his assigns the foresaid land through the foresaid service against all men and women. These things being attested by

Thomas of Ochelee,[4]

Nicholas ?uistch,

William mel.[5]

Roger mel.

Hugh mel.

Godfrey son of Herbert.

Alexander son of Godfrey.

Ralph son of Ulrich.

William, clerk,[6] of Waltham.

And many others.

_____

Notes

[1] Habutat is a rare word that does not appear in R. E. Lathan’s Revised Medieval Latin Word-List from British and Latin Sources (1965–1980). It means “abut” and in fact appears to be a back-formation from either the Middle English form of that word or the medieval French cognate that the Old English Dictionary suggests as its source. I have found it used only in a handful of cases, all of them 13th-century English charters, and all for the same purpose, to describe a boundary of a tract of land. Often it occurs with super, as here, or ad unum caput . . . , as in the second Preston charter [See below], suggesting that these scribes were thinking “abuts upon” in English and then Latinized the verb.

Examples from the same area occur in another 13th-century charter preserved in the Eye Priory Cartulary and Charters, vol. I, pp. 181–185, whose scribe uses habutat no fewer than eight times in one long document, including several times the phrase habutat super as in the Preston documents. The word shows up once in the cartulary of Sibton Abbey (Suffolk), once in a charter of St Paul’s Cathedral relating to Acton (west of London), and a Bedfordshire example too — also all 13th century.

[2] This phrase, which I have rendered here parenthetically, commonly appears in charters as a hedge against the sum named later being determined to be inaccurate.

The previous phrase, iii ob’, should be clarified. Adriano Cappelli’s Lexicon abbreviaturarum suggests that this form of ob’ should indicate some form of “obligation”, but in other charters that I have examined, the phrase et ad plus plus et ad minus minus is always and only preceded by a sum of money, not additional phraseology. Ob’ thus means obolus (or other spelling: Latham’s Revised Medieval Latin Word-List gives various), a ha’penny. Three ha’pennies (iii ob’) seems an odd way to render the sum of one and a helf pence, so it is tempting to assume that the scribe meant “three [pence and a] ha’penny” and omitted the d. for “pence”, but the phrase tres obilos, which explicitly indicates three ha’pennies, shows up in the parallel place in the second Preston charter. (See below.)

[3] According to John Thorley, Documents in Medieval Latin, p. 58, gersuma (and similar: Latham’s Revised Medieval Latin Word-List lists more than a dozen different spellings) can mean “fine” or “payment” more broadly, or more narrowly, “merchet”. The broader definition seems more appropriate here.

[4] Possibly Otley, six miles NNE of Ipswich, about 17 miles east of Preston.

[5] Possibly mel. is sic for mil., which would mean “knight”, but it may be three men with the same surname beginning with mel. Melton, (Long) Melford, and Mellis are all place-names in Suffolk (VCH Suffolk vol.II). Long Melford is only 6 miles away, and for such a small land transaction, near neighbors would be the most natural witnesses.

[6] In the 13th century, this term is ambiguous. It could mean a cleric in minor orders or a literate man (not necessarily in orders) who performs such tasks as keeping the manor court roll and writing out charters. (A given individual could, of course, be both of these things at the same time.) If the latter is intended, this man could well be our scribe himself. By the late 13th century, as surnames became more fixed, it could simply be a family name, but this seems likely given the earlier date of this charter.

*****

Gilbert’s Seal

The fragmentary seal on Preston Charter ‘2’/5 names and perhaps depicts a Gilbert. To judge by the remnants of lettering which precede the name, the seal does not concern a Saint Gilbert —he would presumably be Gilbert of Sempringham (circa 1085 – 4 February 1190), the English founder of the Ghibertine Order. Who knows, the fragmentary central figure of the seal, gesturing with upraised arms in praise or prayer, might depict a devout or holy figure on whose behalf the seal-owner might wish intercession and/or benevolence.

Note that none of the persons named in the charter is a Gilbert. It is not impossible that use of the seal had passed into the hands of one or other of the named individuals — a pattern not unheard of in the medieval period.

*****

Next Case: Charter Number ‘2’ or Preston Charter 5

Deed of Sale of Land at Horsemeso

by Amica, daughter of Albred,

to Beatrice, daughter of Albred, merchant of Preston

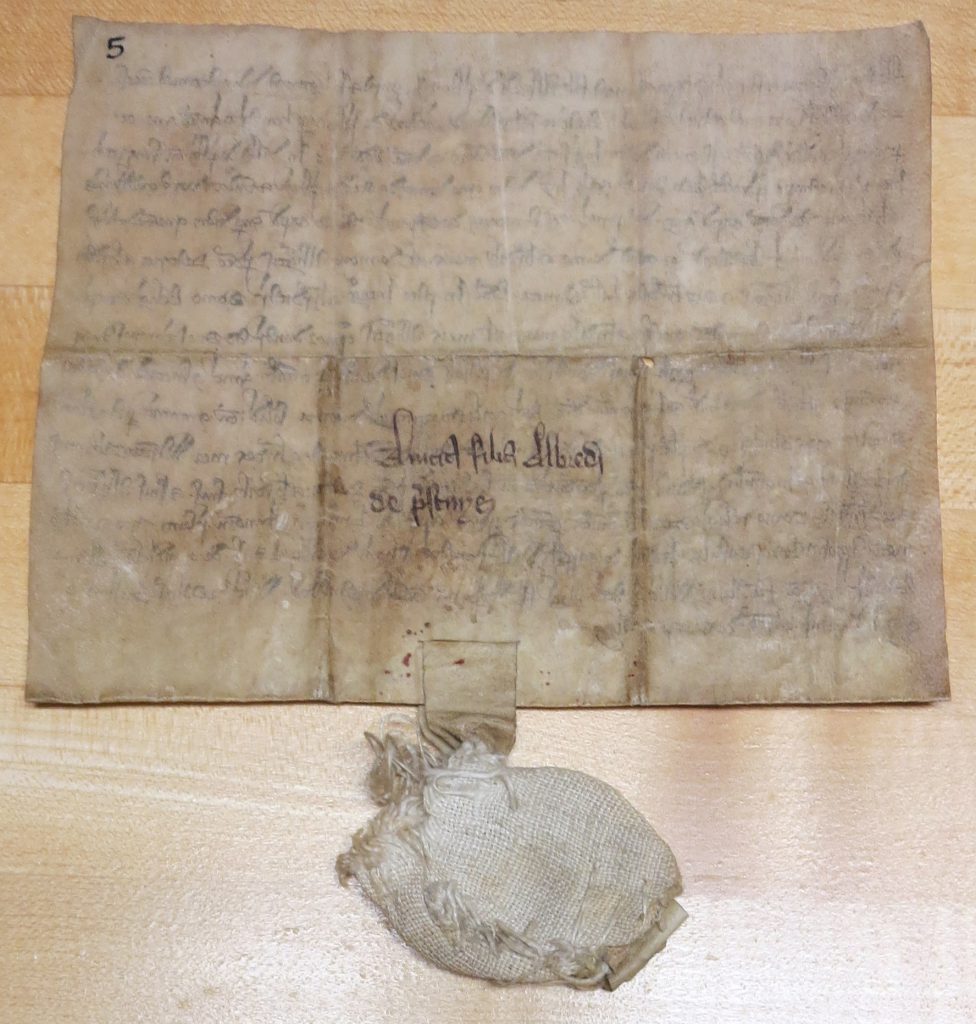

Our next document, likewise undated, also relates to Preston. This one is mid-13th century, to judge by the script. It is written in a single column of 16 long lines by a professional scribe. It has the same type of fold-over, the same sorts of unevenly trimmed edges, and the same sort of laced tag.

But here the seal was fixed to the tag much closer to the document, and it was provided — at some time or other — with a plain-weave rounded textile pouch, made of undyed cloth (probably linen). Intended to cover and protect the original seal, the pouch remains mostly intact, but empty. A cut edge along its bttom has been closed (more or less) with a strip of masking tape (modern), not applied by the current owner. Of the seal itself, there remains not much trace, apart, perhaps, from the size and shape of the pouch.

Dorse

Besides the modern number 5 at top left, the dorse carries a 2-line inscription above the tag.

Preston Charter 5 Dorse. Photograph Mildred Budny.

The docketing inscription written in 2 lines above the tag names the grantor, her father, and a location (hers, his, or the transaction’s).

Amica filia Albredi

de Prestone

Amica daughter of Albred

of [or concerning?] Preston

Face

Preston Charter 5 Face. Photograph Mildred Budny.

Fold, Tag, and Empty Pouch

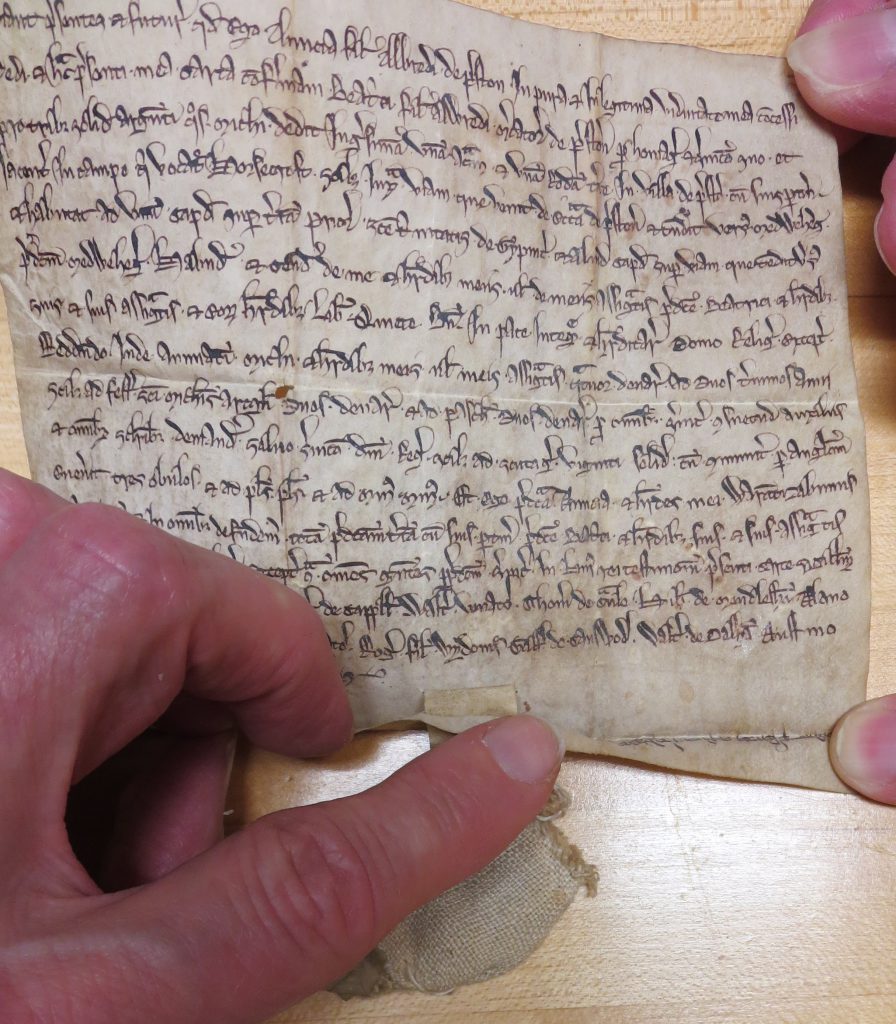

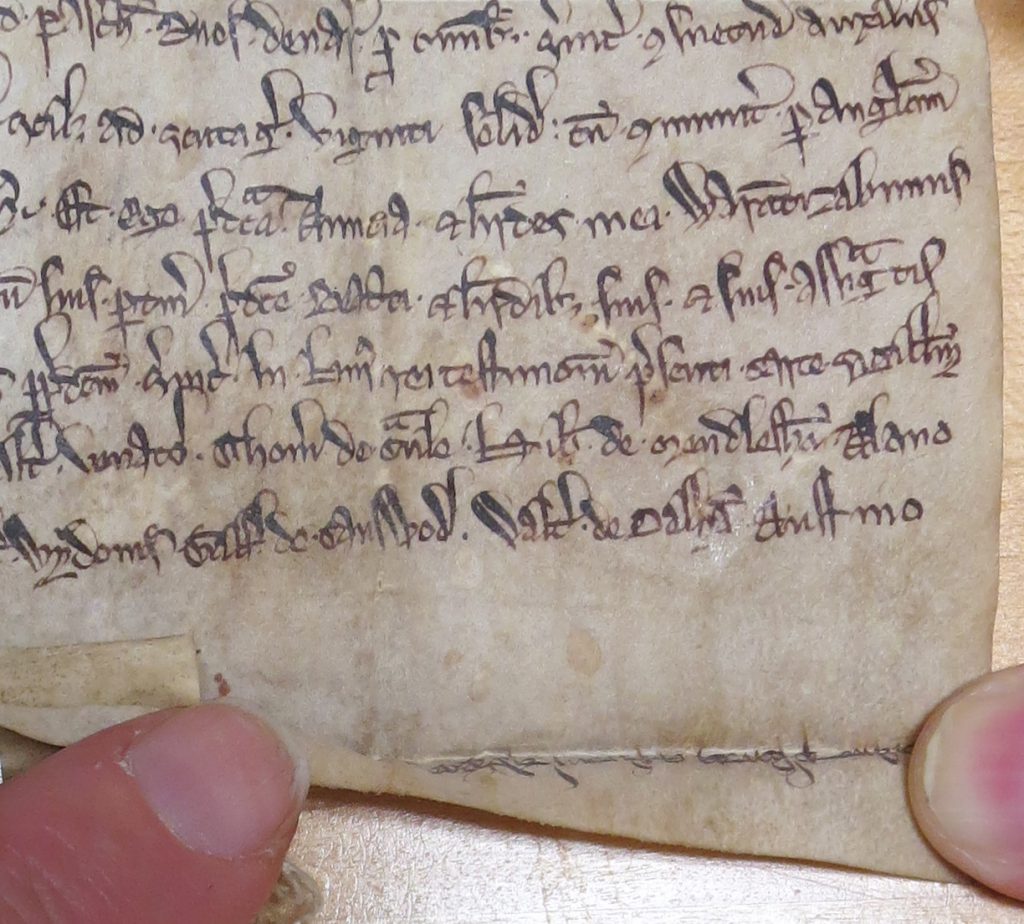

The inside fold-line of the sheet carries a single line of script, set upside-down with relation to the main text. To the left of the seal, the ink of these letters extends in streaks to the edge of the flap.

Preston Charter 5 Face. Photograph Mildred Budny.

Preston Charter 5 Face. Photograph Mildred Budny.

A First Run

The abandoned line of script, now upside-down within the fold, represents a first run at the opening line of a document. This one?

Preston Charter 5, Face, Interior of Fold, Right-Hand Side. Abandoned first line of text of a document, viewed upright.

The Pouch

A close look at the pouch reveals its cuts or tears at top and bottom, as well as frayed threads.

Preston Charter 5 Pouch

We could guess the approximate original size of the seal by the diameter of the pouch. The shape implies a circular seal. Perhaps it survives in some other collection, and its existence may be recognized. If, say, it belonged to the vendor, Amicia, it would belong to the corpus of medieval English seals with female owners.

The view of the Face as we first published it:

The inner fold encloses and mostly hides a line of text written in the original hand. Visible within the fold, it stands to the right of the seal-tag; its show-through appears on the forward-folded dorse. The area to the left within the fold remains blank.

Preston Charter 5 Face. Lifted Fold. Photograph Mildred Budny.

Transcription and Translation

William H. Campbell

1. Transcription

[Line 1]

Sciant presentes et future quod Ego Amicia filia Albredi de preston In pura et in legitima viduitate mea concessi

Dedi et hac presenta mea carta confirmavi Beat[ri]ci filiae albredi mercator’ de preston’ pro homagio et servicio suo et

pro tribus solidi argenti quos michi dedit Ing'[?] firma[?] unam acram et unam rodam terre in villa de preston cum suis pertinen’

iacent’ in campo qui vocator Horsemeso. [???] Iuxta viam que venit de ecclesia de preston et tendit versus medwehe’g.

[Line 5]

et habutat ad unum capud’ super terra priori sancte trinitatis de Gypwc’. et aliud capud’ super viam que tendit versus

predictam medweheg’. Habend’ et tenend’ de me et heredibus meis vel de meis assignatis predicte Beatrici et heredibus

suis et suis ssignatis et eorum heredibus libere et Quiete. Bene. In pace Integre et hereditarie, Domo Religionis excepto.

Reddendo inde annuatim michi et heredibus meis vel meis assignatis quatuor denarios ad Duos terminos anni

Sicilicet ad festum sancti Michaelis archangeli duos denarios et ad pasch’ Duos denarios pro omnibus servit’ consuetud’ auxiliis

[Line 10]

et omnibus secularibus demand’. Salvo servicia domini Regis scilicet ad scutagium viginti solidi cum communiter per Anglia . . .

. . .

Et aliis.

2. Translation

Let all present and future persons know that I, Amicia, daughter of Albred of Preston, have given and conceded and by this, my present charter confirmed to Beatrice, daughter of Alwred, merchant of Preston, for her homage and service, and for 3 silver shillings quos michi dedit Ing? firma? one acre and one rod of land in the vill of Preston together with its appurtenances lying in the field which is called Horsemeso. [???] next to the road which comes from the church of Preston and extends toward Madwehe’g and abuts at one end upon the land of the Prior of Holy Trinity, Ipswich, and at the other end upon the road which extends toward the foresaid Medeweheg’. For the foresaid Beatrice and her heirs and her assigns to have and to hold from me and my heirs or my assigns freely and quietly, well, in peace entirely and hereditarily (apart from a religious house). She and her assigns rendering annually to me and my heirs 4 pence at the 2 terms of the year, namely at Michaelmas 2 pence and at Easter 2 pence,

for all service and custom, aids, and things that may be demanded, except service to the lord King, namely a scutage of 20 shillings cum communiter per Anglia . . .

And others.

*****

Winning Competition

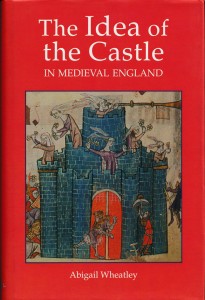

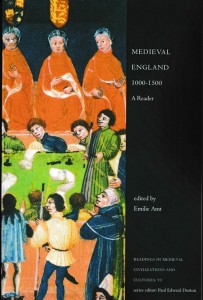

With the publication of this blogpost, we announce the award of the book prizes, as proposed in Full Court Preston, for transcribing and translating the texts of each of these medieval Latin documents. We offered a choice from these Books for the several challenges relating to the texts and the seals:

The choices:

- Reginald Lennard, Rural England, 1086–1135: A Study of Social and Agrarian Conditions (1959, in special edition for Sandpiper Books, 1997), in hardback with dustjacket

- Abigail Wheatley, The Idea of the Castle in Medieval England (2004), in hardback with dustjacket

- Medieval England, 1000–1500: A Reader, edited by Emilie Amt (2008), in paperback

The Winner

We announce the award of two prizes, for transcribing and translating the texts of each of these medieval Latin documents, to William H. Campbell. He supplied first one transcription, then the other, with some revisions and further research, as he continued to explore characteristics of the Latinity and its usage in these and related medieval English documents. The results are published above.

We thank our Associate, William, for his dedicated work, and we offer our hearty congratulations. It has been a pleasure to work with him and to learn more about the workings of the texts of the charters in question. Many thanks!

More to Learn

Preston Charter 7 Seal Face with the name Gilbertus.

We continue to wonder if there might be found

- another impression, somewhere, of the “Gilbert Seal” which survives in part on Preston Charter 7, so that its full features of legend and device (text and image) might be seen

- its original Seal Matrix, from which any impressions would have been made, including this one

- the Lost Seal from Preston Charter 5

- Seals or Seal Matrices belonging to any of the Witnesses named in either charter

- other records which mention the people named as vendor, buyer, or witnesses in those charters

- other documents written by their scribes

- the missing Charters 1–4 and/or Charter 8 — or any possible Charter 14 and higher? — of this consecutively numbered sequence of Preston Charters

We look forward to learning more.

*****

We thank the owner of the documents for permission to reproduce the images and to invite further research.

We look forward to your suggestions. You can contact us via Contact Us or our Facebook Page. Comments here are welcome too.

More to Come. See our Manuscript Studies Contents List.

[Now see Preston Charters Continued.]

*****