Scrap of Information

August 7, 2015 in Manuscript Studies, Photographic Exhibition

The Scrap

Continuing our series on ‘Manuscript Fragments’, starting with Lost and Foundlings and still focusing on the Handlist of Medieval and Early Modern Materials, we showcase Handlist 22, the Scrap of a 16th-Century Charter on Vellum in French.

[Posted on 7 August 2015, with updates]

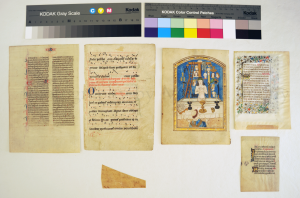

Earlier posts about the Handlist included a Preview which showcased the Front & Back Views (as in Both Best Views) of this ‘Scrap’. Those Views included a measurement scale and a color guide, which help to show(case) how small and seemingly inconsequential the Scrap can seem. There it is, Bottom Sort-of-Center in the Group Portrait.

Inconsequential? Not necessarily. Worth a closer look.

Meet & Greet

Please meet Handlist Number 22. Up front & back & center stage.

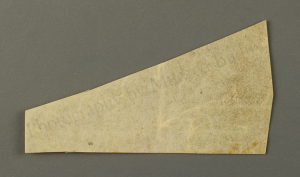

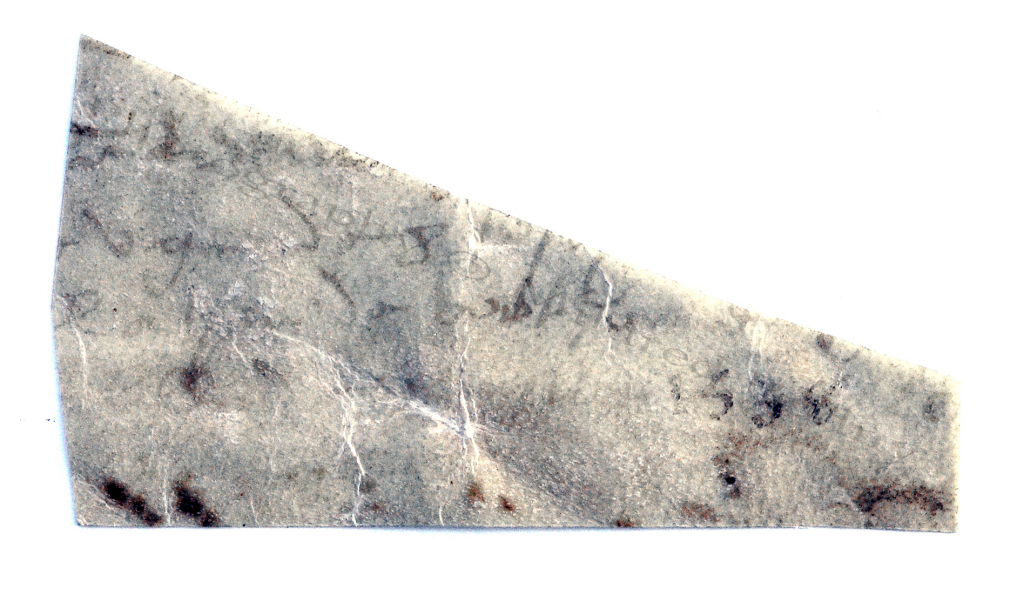

It survives as the scrap of a document, trimmed into a sub-trapezoidal shape, leaving parts of 4 lines of script in French. The yellowed hairside of the animal skin serves as the recto of the document, with its text, while the whitish fleshside remains bare.

The scrap measures circa 63 × 118 mm. No more than a sliver, really.

No idea what would have been the original written area, now reduced to this scrap having only the parts of lines. No idea, that is, except that it was bigger. By how much? Wish we knew.

Go Figure

Anyway, there is the date. Or number. Or ‘Trap’.

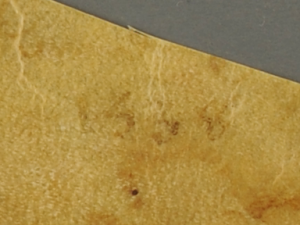

Closer inspection under different lighting can work wonders. As here:

The Arabic number ‘1538’ appears prominently, especially clearly when variously illuminated. It occurs as the single written element, offset to the right, in — or rather alone as — line 4 on the scrap. Let’s say it’s the date, or a date.

Taking It From the Top

Let’s start with Line 1 (as represented by the surviving scrap). This is the only original line; the others are added later. Ignoring the stroke at the top, presumably a bit of the preceding line now lost almost in full, this line appears to read

l’an d[omi]ni mil . . . (‘the Year of the Lord [One] Thou[sand Something-or-Other must have followed] . . .’).

The next two lines add partial information, so far partly decipherable.

Line 3 appears to end, including a fancy capital O, with this:

‘ . . . d’un Obligation’ (or ‘Oub . . .’).

Then comes the 1538, the sole occupant of Line 4.

The Layered Effect

In other words, this little scrap appears to preserve layers of information pertaining to a record or records which received written attention over more than one time.

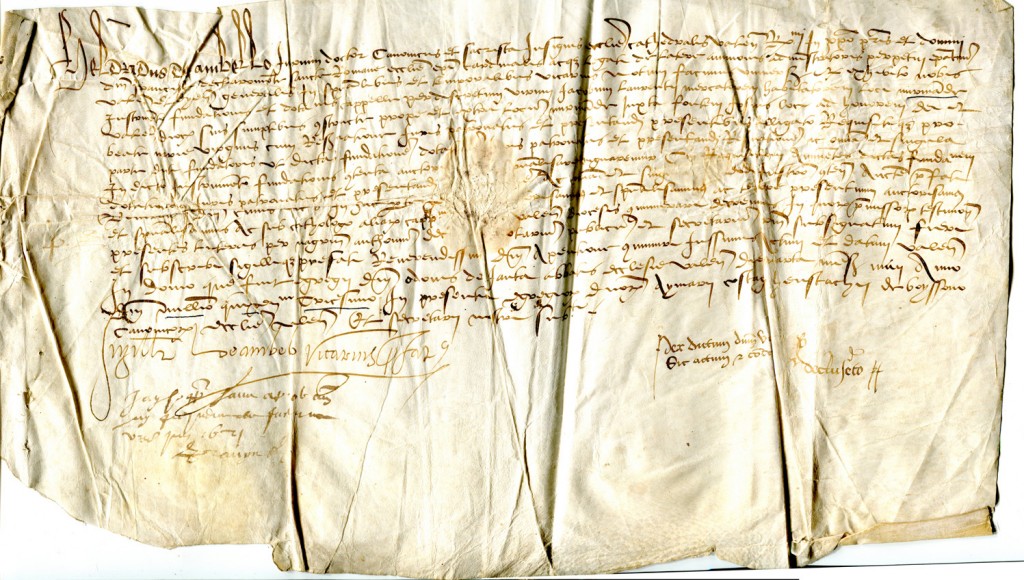

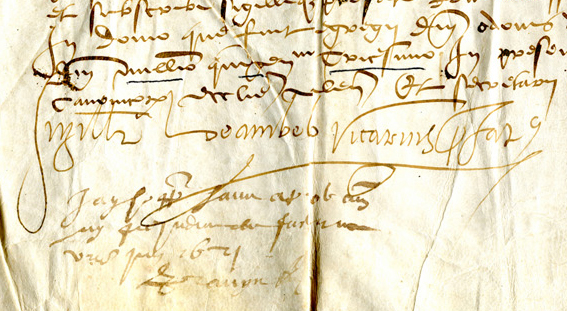

Judging by the script, the hand of the first line seems to date approximately from the 1530s. An example from this date, in a single-sheet charter in Latin concerned with a transaction at Vienne, in Isère, France, is shown here (from a private collection, reproduced with permission).

That document likewise has entries by more than one hand, in different styles of script, and in different shades of ink. Its text extends for 16 long lines, including the record in the penultimate line of the date of 1530 in Latin, for which a set of 3 underlines in dark black ink marks out this significant element. Presumably the underlines belong to a much later date, perhaps close in time to the preparations for selling the object. Below the text appear 4 inscriptions in 3 columns, beginning with the expansive and flourished signature of the principal (reading in part ‘Deambelo Vitarius’), and continuing directly below with another hand’s cramped 4-line inscription partly overlying or underlying the flourish.

Such overlap and repeated interventions on a larger scale in a whole document (albeit damaged) may illuminate the compacted layers of accretion on the Scrap.

The original script (Line 1) on the Scrap is not unlike that of an autograph letter written by the distinguished bibliophile Jean Grolier de Servièrs (1489/90 – 1565), Vicount d’Aguisy, during the period when he served as Treasurer General of France (from 1537). The letter is preserved, and sometimes on view, at the Morgan Library. In other words, these two hands exhibit a similar approach, fluidity, and assurance in swiftly crafting the characters. Although different hands, they share the same approximate time-frame in the training and practice of handwriting.

The rest of the text on the Scrap is ‘docketing’, and dates to considerably later. Its function is to mark goods with a label listing the contents.

To judge by the script, that part dates probably to the late 16th century or the 17th, and it appears to have been entered by more than one hand. Including the entry of ‘1538’. Its presence presumably records the date of, or a date mentioned in, the text of the original charter.

Trap

That entry could, for all we know, be accurate. Nor do we have any reason necessarily to doubt it. Because the layers of accretion on the Scrap indicate entries at more than one date, even on so small a sample, it is appropriate to question each and every scrap of entry upon this fragment.

That the date 1538 (presumably a date) is entered in a script not consistent stylistically with the stated date, it is appropriate to consider this specimen as an Excellent Case of a ‘Palaeographical Trap’. That type of Trap could fool us, if we let it, by giving indications of one period of time while belonging to another one far, or somewhat far, from it.

That the date 1538 (presumably a date) is entered in a script not consistent stylistically with the stated date, it is appropriate to consider this specimen as an Excellent Case of a ‘Palaeographical Trap’. That type of Trap could fool us, if we let it, by giving indications of one period of time while belonging to another one far, or somewhat far, from it.

I learned this term from one of my teachers for Palaeography as part of the M.A. Course (in English Language and Literature before 1525) at the University of London. This was Andrew G. Watson, who gave much advice through the years for various of my individual and collaborative projects, and he contributed to some seminars of the Research Group on Manuscript Evidence (for example this one). His wry smile as he said the words ‘Palaeographical Trap’ is worthy of cheerful remembrance.

Over the years, I came to meet some more Palaeographical Traps in various manuscripts, up close in person.

One of my favorite examples is the late 11th- or early 12th-century copy of De Temporum Ratione (‘On the Reckoning of Times’), by the Northumbrian Bede (672/673 – 735), and some other computistical texts, made at Saint Augustine’s Abbey, Canterbury, and now at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, as Manuscript 291. Number 49 in my Illustrated Catalogue. In its calculations, the text of the Pseudo-Bedan computus mentions the date 831 in the present three times, so the copy evidently derives from an exemplar produced then, and makes no effort to recalculate the date for the time of copying. The date of 831 is palaeographically impossible for the manufacture of MS 291. Its script and decoration correspond to styles practiced at the abbey in the Anglo-Norman period, and the starting date of the Easter tables with the year 1064 gives a starting point at which, or after which, the copy was produced.

See how tricky it can be? Time travel in the span of a few pages.

In the case of the Scrap, the time travel hastens across only a few lines. Whew! That was fast!

Thinking of a Number

It cannot be considered, not even for a moment, that the inscriber of the date on the Scrap intended to fool us. Adding notes to earlier materials — documents included — for their ready identification at a glance, without having to bother with reading the whole thing (and, when it comes to it, having to decipher it, sometimes with difficulty!), is part of standard practice in sorting through archival or other records. More for us to discover! That is, provided any scraps of information at all remain for our viewing pleasure.

And as for the close shave, perhaps you can see the tiny sliver of parchment which rises along the upper slope of the fragment? Thus shifted the blade of the knife in repositioning itself for the next part of the slice.

Finally, it is worth reporting that the present owner does not recall when or where the scrap reached the group of materials now assembled in the Handlist. He wonders if it traveled as a patch, perhaps, for or on something else. Such might account for the seemingly odd shape.

When I first met the Scrap, among the first items which the owner entrusted to me for photography, observation, research, and (where indicated) conservation, it arrived loose, on its own. Anyway, now it can begin to speak to us.

Perhaps sometime its former location in an original document might become knowable. What do you think?

*****

Next stop: Another item in the Handlist. I pick Handlist 7, A New Leaf from ‘Otto Ege Manuscript 61, shown at the Top Right in the Group Portrait above. See you there!

*****

Update July 2020

Beside the 2 documents examined here,

- the Scrap with the number or date 1538

- the Document of circa 1530 from Vienne, Isère

see also the reports on other 16th-century documents in French on vellum:

- Say Cheese, with a survey of rents for plots of land, circa 1530s, from Brie, Isère

- Vellum Binding Fragments in a Parisian Printed Book of 1598, from a legal document of circa 1510 to 1520

Please let us know if you know of other documents like these.

You might reach us via Contact Us or our Facebook Page. Comments here are welcome too.

Watch for more discoveries. See the Contents List for this Blog.

*****

[…] Budny, “Scrap of Information” (Blog for Manuscript […]

[…] From: http://manuscriptevidence.org/wpme/scrap-of-information/ […]

[…] Budny, “Scrap of Information” (Blog for Manuscript […]