Document on Paper from Grenoble,

Dated 22 February 1345 (Old Style),

With a curious Seal

[Posted on 20 June 2010, with updates]

Mildred Budny reflects upon a fragmentary document, its enigmatic wax seal, and the mid-14th-century owner of the seal.

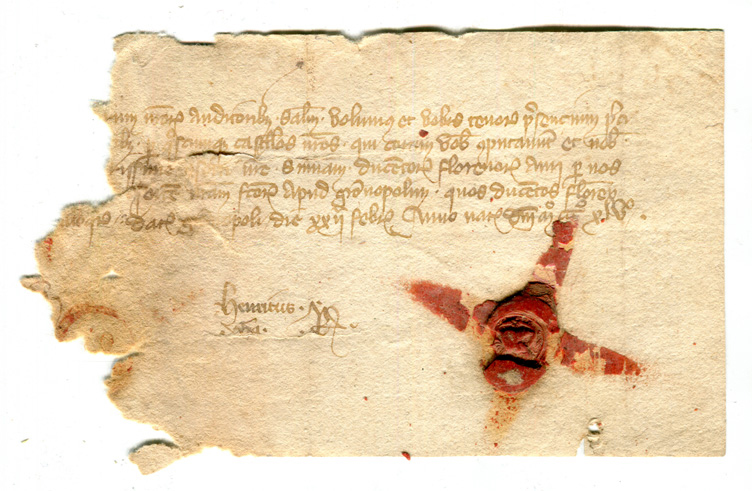

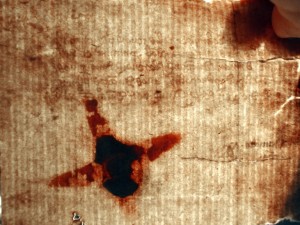

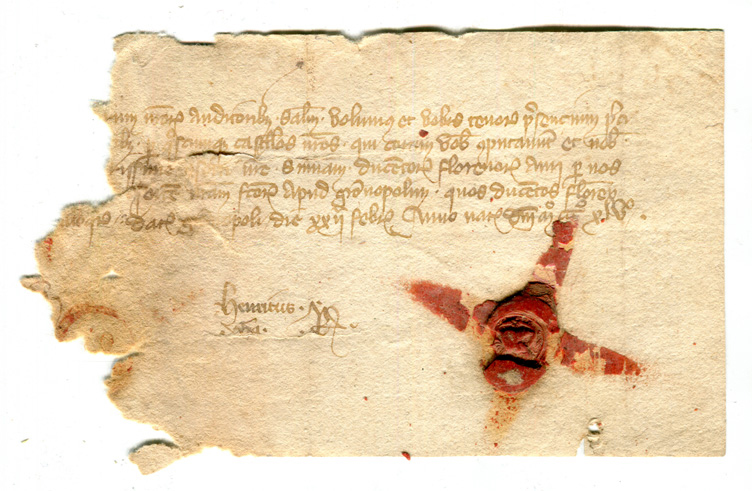

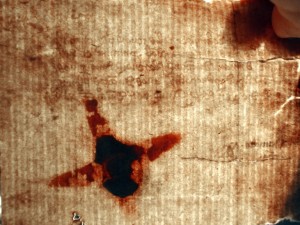

Today we showcase the fragment of a documentary record on paper which has traveled across time and space to find renewed attention. Among its curiosities, it carries a seal in red wax depicting a male human head accompanied by creatures and part-creatures drawn from the animal, avian, and insect realms. Now in a private collection, the document was recently purchased online from a seller in Isère, France, not far from its place of origin in or near Grenoble nearly seven centuries ago.  Reproduced here by permission, the fragmentary document written in Latin on paper records a transaction conducted apud Gratianopolis (‘at Grenoble’) in the Dauphiné” (now France), with the date of 22 February 1345 Old Style. The left-hand side of the document has been roughly torn away, with the loss (of uncertain extent, probably about half) of the first part of the lines of text.

Reproduced here by permission, the fragmentary document written in Latin on paper records a transaction conducted apud Gratianopolis (‘at Grenoble’) in the Dauphiné” (now France), with the date of 22 February 1345 Old Style. The left-hand side of the document has been roughly torn away, with the loss (of uncertain extent, probably about half) of the first part of the lines of text.

Map it Out

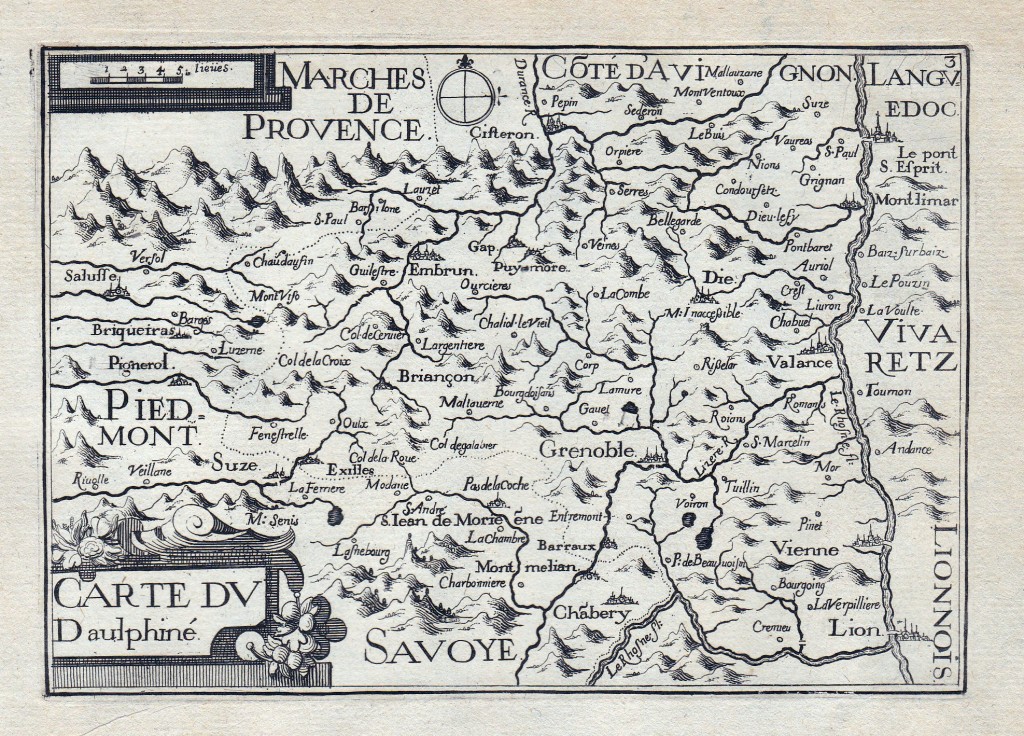

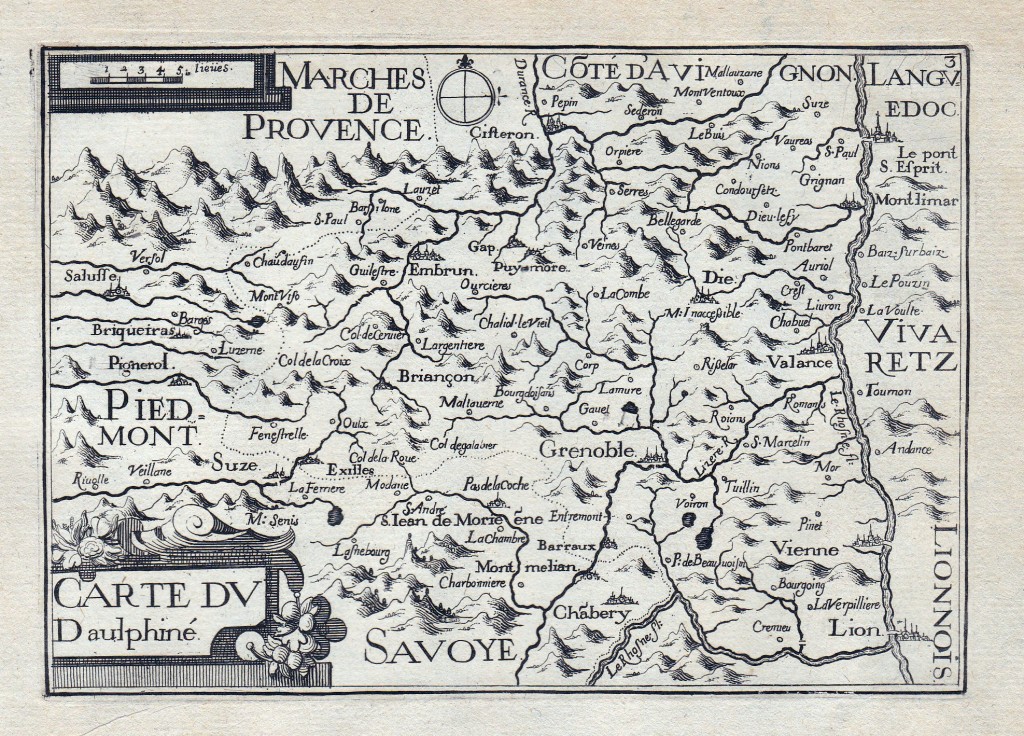

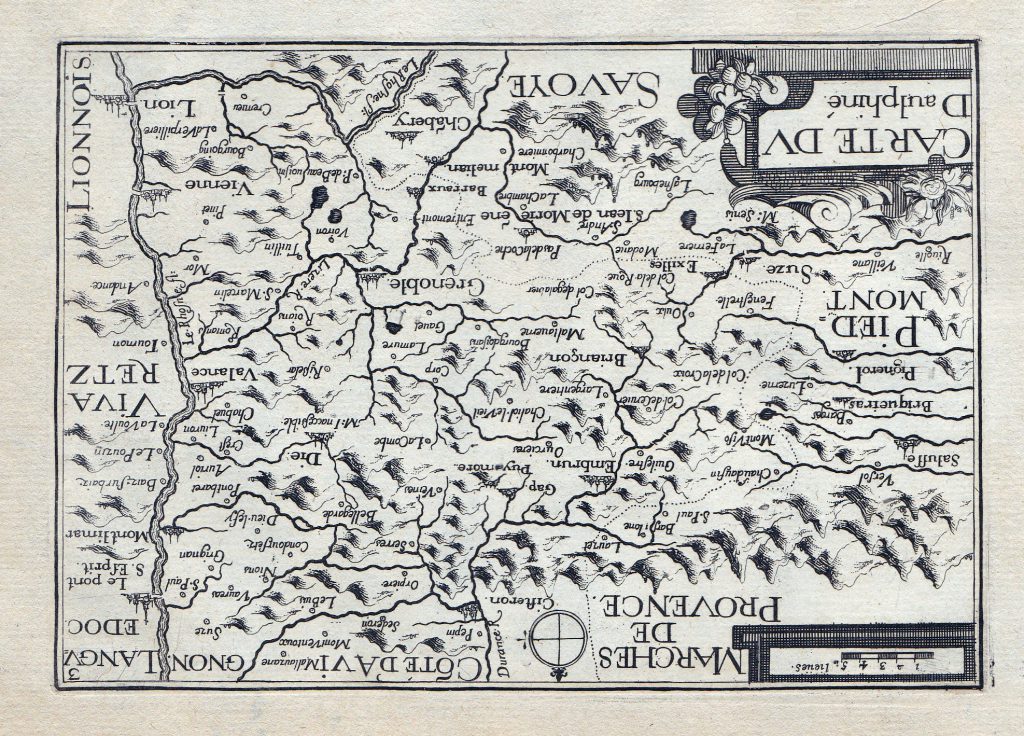

The ‘Carte du Dauphiné’ by Christophe (or Nicolas) Tassin (died 1660), printed in 1630, sets the scene.

‘Carte du Dauphiné’ by Christophe (or Nicolas) Tassin, printed in 1630. Private Collection, reproduced by permission.

[Update: A Comment by Wales Legerwood on 11 January 2022 observes: “I have this map in my collection. Interesting that the north arrow of the compass rose as drawn on this particular map is engraved pointing in the wrong direction: south. It should be rotated about 180 degrees.”

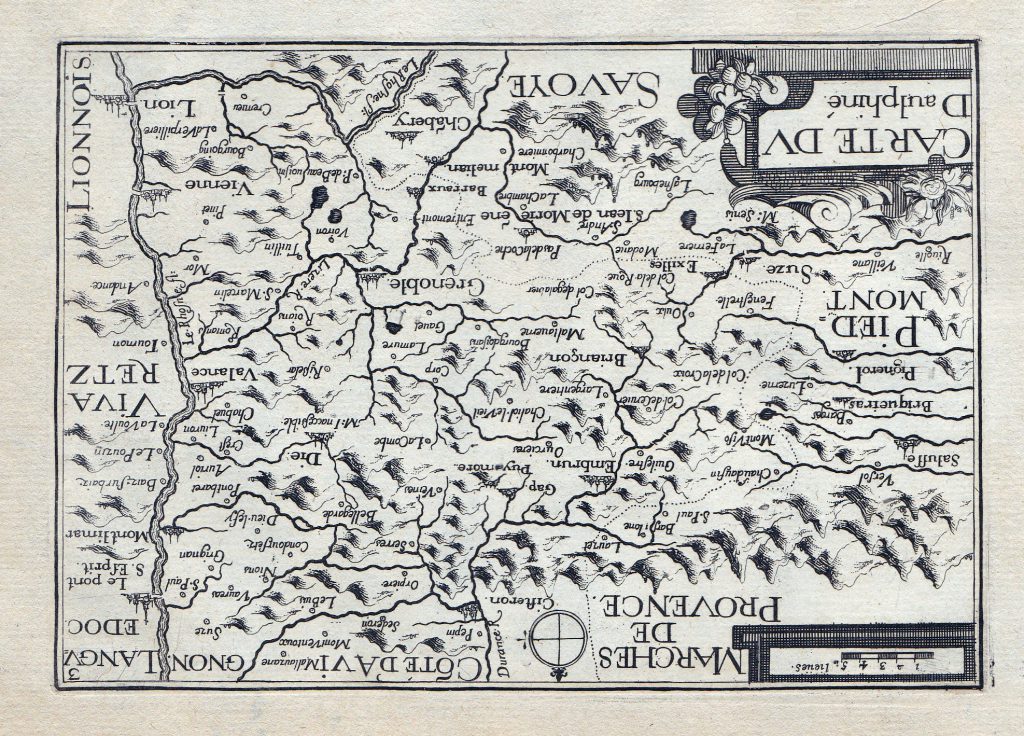

‘Carte du Dauphiné’ by Christophe (or Nicolas) Tassin, printed in 1630. Private Collection, reproduced by permission.

[A map printed a few years later by the same cartographer shows another view.]

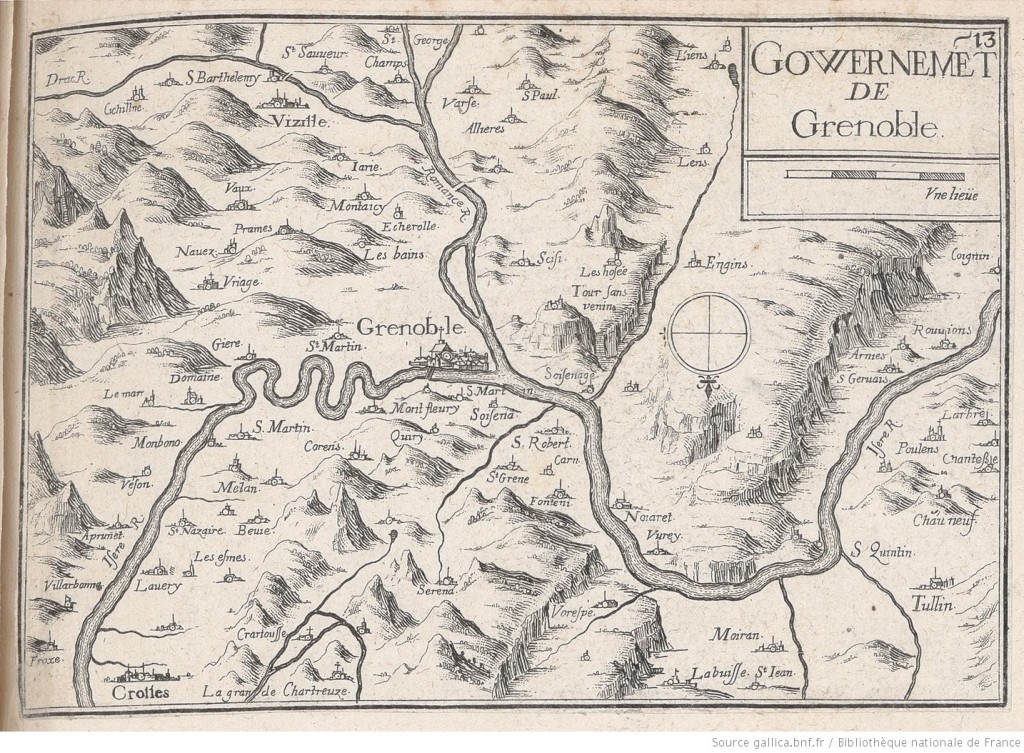

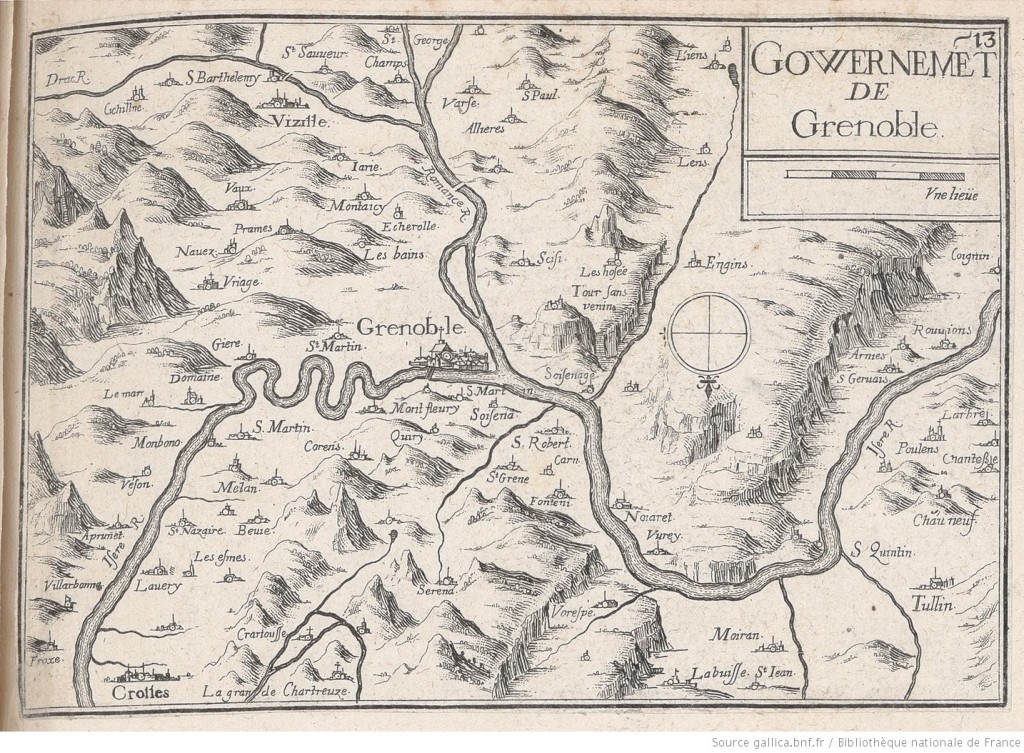

Govvernement du Grenoble. ‘Plans, vues et cartes du Dauphiné’ by Christophe Tassin (1634). Via gallica.bfn.fr.

Seal the Deal

Written in an expert cursive documentary script in brown ink by a single scribe, the 5-line record is ‘signed’ or attested by the double names of Henricus in full (‘Henri’) and the abbreviated Joha[nnes?] (‘Jean’?), accompanied by a tall monogram or cypher to their right. Both the single names and the cypher are flanked or surrounded by dots, setting them off as names and/or signs as such.

The names and cypher are written in 2 lines by a single hand, perhaps different from the main scribe, in a more compressed upright script. The names are flanked by dots. The cypher, both flanked and surmounted by dots, perhaps combines their initial letters h and J in an elegant flourish.

If the names pertain to a single individual, during this period the combination implies a person of some importance worthy of a first and a second name together. Both the names and the cypher manifest an accomplished hand. If written by their named individual, they manifest his scribal training to proficiency and, perhaps as well, a commensurate degree of literacy.

The names may hold some clue(s) to the meaning of the Device (that is, images) on the Seal, which bears no Legend (that is, inscription) to aid, compound, or delight the process of its decipherment. Perhaps deciphering the one in time may speed the decipherment of the other.

The names may hold some clue(s) to the meaning of the Device (that is, images) on the Seal, which bears no Legend (that is, inscription) to aid, compound, or delight the process of its decipherment. Perhaps deciphering the one in time may speed the decipherment of the other.

Whoever their owner, the complexity of the design on the Device and the manifest skill of its execution demonstrates an imposing, and perhaps comparably idiosyncratic, identity for this Henricus Joha[. . . ], whose second name could be Johannes (or the like). It is worth recognizing, however, that, given late medieval naming practices in many regions, the abbreviation for a second name or surname could stand for a place-name, an occupational name, a nickname, or some other appellation, rather than a personal name.

The seal in red wax affixed directly to the page to the lower right of these 2 names depicts within a now-fragmentary roundel the image of a male human head seen in profile with a straight nose, both beard and moustache, and either a conical helmet (albeit without any rim) or an elongated, distorted skull formation. As it stands on the page, sealed in wax, the head faces downward, but when it is seen upright, the head faces left.

On the page to the left of the names Henri and Jean[?] there appear the remnants in red of a rimmed element and other elements pertaining either to the offset of this seal (for which no folds on the document bear obvious witness) or perhaps to another attestation of unknown identity, now mostly effaced.

Paper Trail

The paper itself carries no watermark, unfortunately, but the surviving remnant of the document is a small portion of the original sheet of paper. The lines within the paper, however, are very different from those found on later samples, so that the specimen merits interest as an unusual survivor in the history of the development of European paper.

Back-lighting, as seen here, reveals the structure of the lines more clearly. More posts about this subject, plus a gallery of specimens of European paper across centuries, are in preparation for our website.

Wax Lyrical

Different levels of side-lighting, shown here, reveal more of the details of the Device on the seal. Its features are curious, to say the least.

Different levels of side-lighting, shown here, reveal more of the details of the Device on the seal. Its features are curious, to say the least.

At the base of the human neck appears the frontal face (or ‘mask’) of a lion-like creature, which grips in its jaws the base of the long neck of a wide-eyed, winged goose-like creature, seen in profile, crouched beneath the human head. Fanned plumes or a crest rise(s) above and in front of the head or, it may be, helmet. Details to the fore of the face seem difficult to discern, perhaps an indication of some wear and age to the seal matrix. Such ‘blurred’ or fragmented features could suggest that the matrix had received much use, perhaps from being handed down within a family.

A knob-like extension at the crest of the head-or-helmet leads to the base of some formation lost in the damaged ‘apex’ of the field. Behind the rounded back of the head stretches a skinny lizard-like creature, seen from above, rising or crawling above the goose’s head toward the ‘top’ of the scene. Damage to the seal (or imperfection in its impression) at the right of the lower half of the ‘lizard’ perhaps removed some element in the scene. The goose’s closed beak clamps onto the remnant of lizard’s right hind-leg. A curious combination.

The depicted food chain appears to defy biology. But it does pique curiosity. Human Neck —> ‘Lion’ Mask —> ‘Goose’ —> ‘Lizard’. Huh?

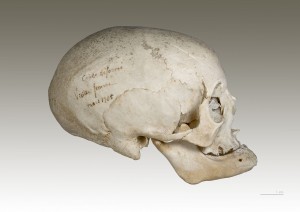

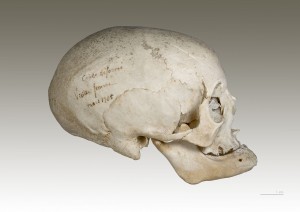

«_déformation_toulousaine_»_MHNT (Author Unknown / restoration and digitization. Didier Descouens / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain)

Skull-Duggery

Curious, too, is the elongated shape of the skull, which might or might not be ‘natural’. The shape appears deformed, like the cranial deformation of human heads or skulls observed in many parts of the world across the centuries or millenia, whether biological or artificial. Widely ranging examples include many ancient Peruvian skulls (from circa 6000–7000 BCE onward), ancient Egyptian examples from the sphere of the Pharoah Akhenaten (1375–1358 BCE), manifestations in art and the archaeological record through many periods of Mesoamerican Mayan culture, and recognized cases of skulls among East Germanic and Huns peoples in migration in the early medieval period in the West.

[Update: Newly discovered is a ‘Conehead’ skeleton, approximately 2,000 years old, of a woman of the Sarmati tribe excavated at Arkaim, near Chelyabinsk, in the southern Urals.]

Such practices reshaped the heads of some humans, for whatever reasons, perhaps or apparently involving prestige. Both the evidence and the issues remain subjects of fascination and controversy. For example, not all cases which have been considered as representatives of the habit still qualify, as with a Proto-Neolithic skull from Shanidar (circa 300,000–30,000 BCE), previously believed to comprise the earliest known example but now differently reconstructed. But the amplitude of the bodies of evidence for alteration of the shape of skulls through human intervention provides a source of wonder. The practice of intentional cranial deformation, in different manifestations across the centuries in many parts of the world, could produce a ‘permanently visible symptom of social affiliation’. So prominent a feature is hard to miss.

It seems that, in certain contexts, head shape demarcates membership and hierarchies within social or ethnic groups among larger societies, with some apparent manipulation of shapes in the pursuit of demonstrating, or cultivating, affiliations with groups or individuals in power. The wide range of observable cases of skull deformation globally has been the focus of medical study and classification, for example by Eric John Dingwall (1931) (freely available in full online) and by Amit Ayer, Alexander Campbell, et al. ‘The Sociopolitical History and Physiological Underpinnings of Skull Deformation’ (2010).

Not all cases of strange skull shapes are deliberate, of course, but, whatever the case here in the wax seal, the outcome — if it represents head-shape rather than helmet (which might, presumably, be removed at will) — would be permanently, irrevocably visible for all to see. Perhaps for some it would have been a source of awe, if not admiration.

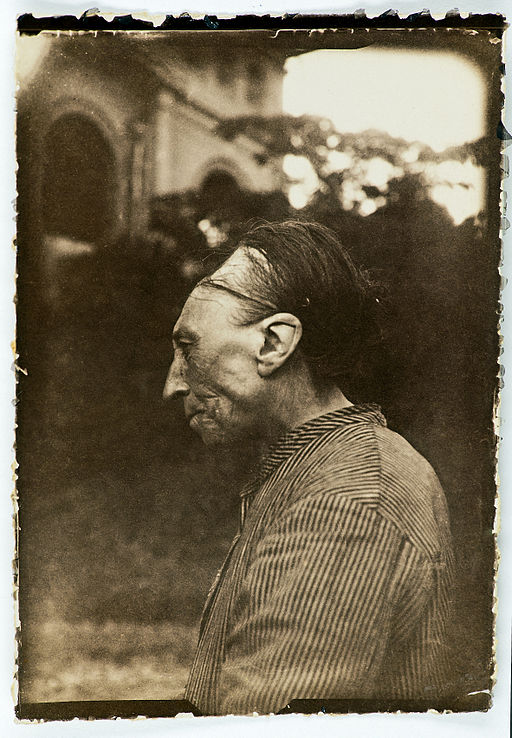

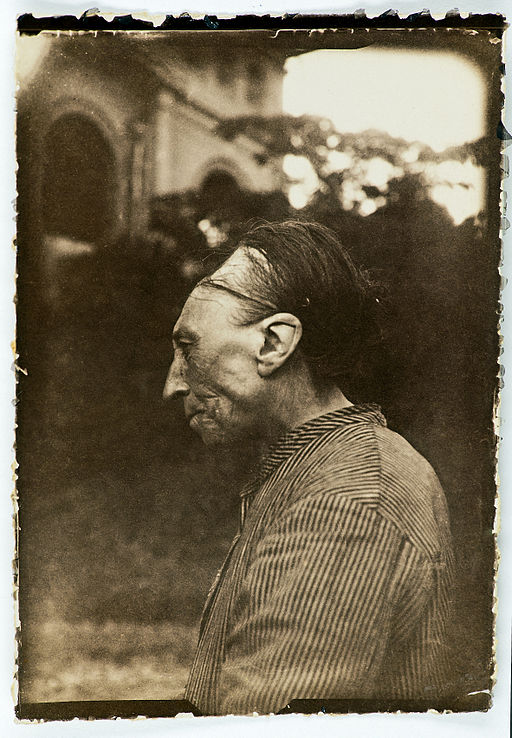

Such aspirations for altering physical characteristics of a specific, and visible, part of the human body seem to have governed, for example, the practices of Chinese foot-binding. The late survivors of that practice make it possible to interview, as well as to photograph in the flesh, some living witnesses.

In a way, the seal of Henry J. itself might give us a glimpse, close-up, of his particular, if not peculiar, characteristics, along with some choices of his own about elements outside his body (animal, etc.) to express his identity on the page.

A Medieval Case of the ‘Toulouse Deformity’?

Déformation toulousaine – Muséum de Toulouse. « Crane déformé 1905 MHNT » par Didier Descouens (Own work), via Wikimedia Commons

Curiouser for the presence of our seal on a Grenoble document is the persistence of such a custom, altering the shape of the human cranium by artificial distortion, in parts of Southern France until rather recently, as described and illustrated, for example, in the Wiki articles on Artificial Cranial Deformation or Déformation volontaire du crâne. This ‘deliberate deformity of the skull’ is known as the ‘Toulouse deformity’. In this style or type of cranial deformation, a tight cap is placed upon the head, or a band is wrapped around the cranium to compress it into a circular shape, which expands upwards into a cone.

The study of ‘Later Artificial Cranial Deformation in Europe’ (1931) observes that such practices in recent centuries centered upon France. Perhaps the elongated conical shape of the head on the wax seal formed in 1345 bears witness to the custom as a revival or survival of earlier practices, in their transmission variably across time within or across regions.

It’s a Stretch

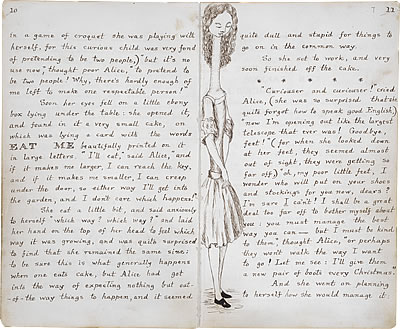

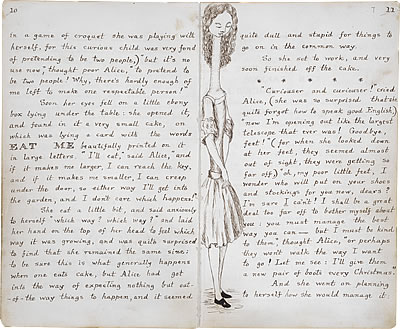

It seems not inappropriate to consider in this connection the condition — not entirely a predicament — of being ‘stretched tall’, in which Alice found herself to appear in Wonderland (1853), under the heading of Curiouser and Curiouser.

©The British Library Board, Add. MS 46700, pgs 10-11. Reproduced by permission

“Curiouser and curiouser!” cried Alice, (she was so surprised that she quite forgot how to speak good English,) “now I’m opening out like the largest telescope that ever was! Goodbye, feet!”

The author’s original manuscript of the first version of the text, now in the British Library, illustrates Alice’s elongated form as envisioned by her creator ‘Lewis Carroll’ (1832–1898), whose pen-name itself is a confection.

The similarly elongated neck on the seal enters a world of fantasy and imagination with its combination of creatures somehow integrated with the human world, both seemingly easily and not so much.

Skull-asticism

Whether the image on the seal represents, or is intended to represent, a given human individual rather than some fanciful being, the combination of creatures clustered around his head suggests a puzzle or word-play. Within the complex, wide-ranging world of medieval seals and their molds or matrices, there were multiple forms of presenting, or combining, images of one kind and/or another, with or without text. Many other medieval seals, too, draw upon non-heraldic structures — that is, elements not specifically assigned (as yet) in the time-honored code of heraldry, according to specific rules for devising heraldic coats of arms of rank for persons, families, dynasties, towns, cities, and other organizations.

Non-heraldic forms on seals can indicate in less formally codified, but not necessarily less rigorously chosen, elements to indicate, or to suggest, the identity, name, occupation, preoccupations, predilections, or other characteristics of the owner of the seal. Many cases, which we in the Research Group on Manuscript Evidence have had the opportunity over recent years to study in detail on site over time, occur within the remarkable selection of medieval seal matrices and documents assembled in the Collection of our Associate John H. Rassweiler and now presented in part as the Rassweiler Collection Online.

The ensemble in Henricus J.‘s seal confirming a transaction in Grenoble in 1345 may, for example, function as a form of rebus, with an allusion to the owner or his identity in some way, or as the visual illustration of some proverb, in a motto for his or anyone’s consideration. Such practices are not uncommon in shaping the Devices of medieval European seals.

The ensemble in Henricus J.‘s seal confirming a transaction in Grenoble in 1345 may, for example, function as a form of rebus, with an allusion to the owner or his identity in some way, or as the visual illustration of some proverb, in a motto for his or anyone’s consideration. Such practices are not uncommon in shaping the Devices of medieval European seals.

Or, could we say, such practices may be most uncommon, although widespread. Common and Uncommon: that combination could be right for this seal’s Device. Its designer may have smiled to think of the curious combination.

Within the genre, this Device seems remarkably ingenious. The script of its owner’s ‘signature’ could indicate that he was well educated.

Dare we say Cerebral?

Its answer, or solution, may yet come to light.

You Think?

More research might illuminate the context of this document, reveal more of its original text, identify the person(s) involved in its record and attestation, and provide the key to its curious seal. Perhaps you could help with suggestions and information.

We invite you to contribute to the exploration – and its adventure.

Please leave a Comment here, Contact Us, or join the conversation on our Facebook page.

P. S. In the conversations about this Post, one of our friends called it a case where ‘Codicology Meets Craniology’. Cool.

*****

[Published on 10 June 2015, with updates]