A 12th-Century Fragment of Anselm’s ‘Cur Deus Homo’

January 31, 2017 in Manuscript Studies, Reports, Uncategorized

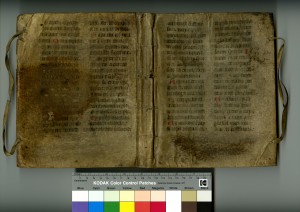

Tied Down

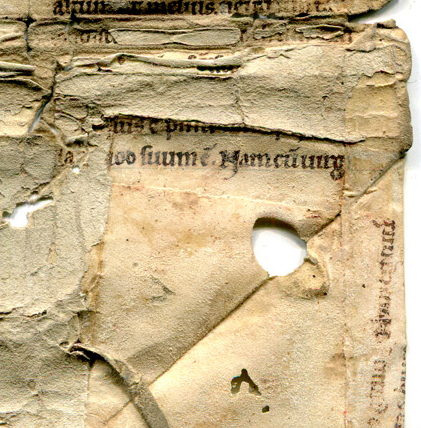

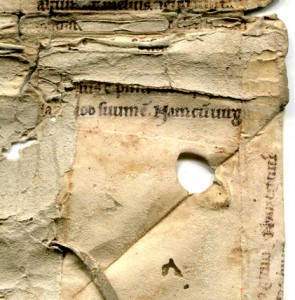

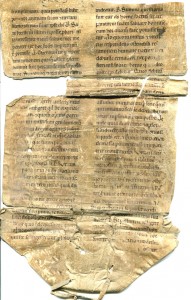

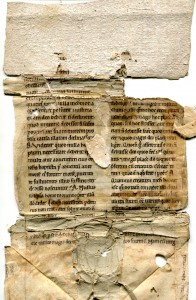

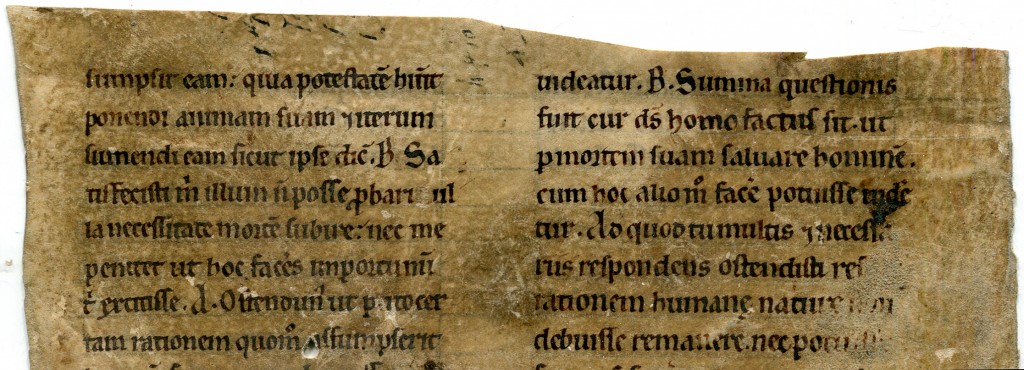

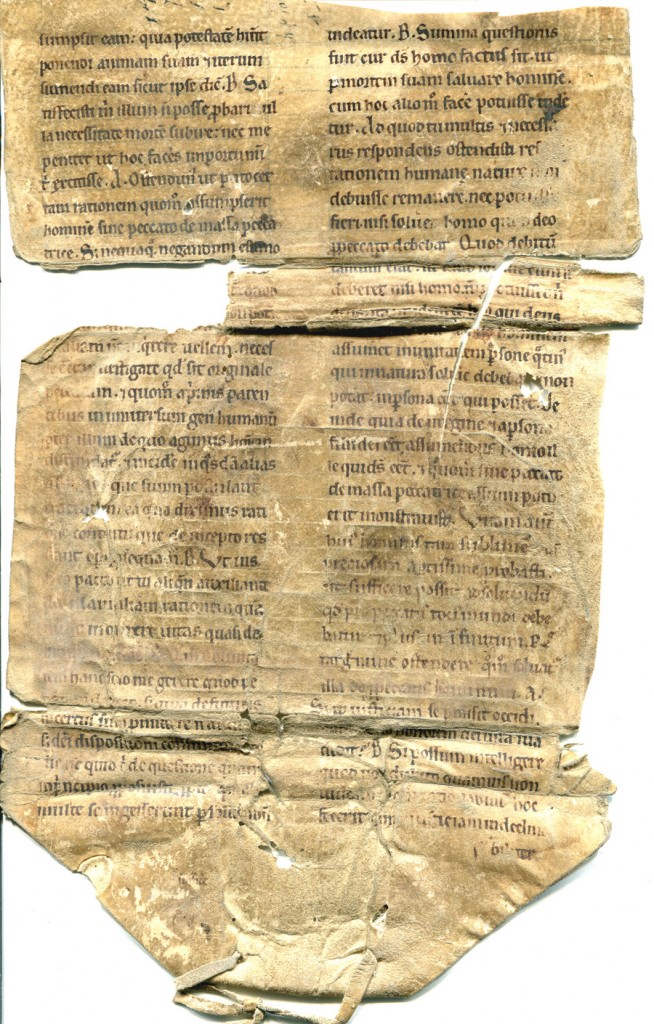

Fragmentary Leaf with Part of Anselm’s Cur Deus Homo

Book II, Chapters 17–18 or 18a–b

(sumpsit eam . . . Nam cum uirg[/initatis melior])

in Latin on vellum

measuring at the most circa 307 mm tall × circa 182 mm

< written area (including ascenders and descenders) 148 mm wide

with each column circa 65 mm wide

flanking the intercolumn of circa 18 mm wide >

laid out in double columns of 35 lines

written in brown ink in skilled ProtoGothic script

without embellishments

Continuing our series on Manuscript Studies, our Principal Blogger, Mildred Budny (see Her Page) reports the discovery of a reused fragmentary vellum Latin manuscript leaf extracted from a copy of Anselm’s masterwork Cur Deus Homo. Whether as a text on its own or in the company of other texts, it was made probably in about the third quarter of the 12th century, to judge by the script, perhaps in France. Norman, maybe? Identifying the text and its sequence makes it possible to recognize which side of the leaf was the original recto, and which the verso. The fragment joins the select known cast of 12th-century manuscript witnesses to this significant philosophical–theological text.

Anselm’s texts mostly took the forms of meditations or dialogues. Already our blog has showcased a manuscript with another text by Anselm: A New Leaf from ‘Otto Ege Manuscript 41’, which formerly contained a copy of the Prayers and Meditations. Now we focus upon one of his principal dialogues, cast between master and follower, as they debate the natures of divinity and necessity.

Location or Find-Place

Now in a private collection, the leaf was purchased recently online from a seller in Thionville (see some more information about the place in French), on the Moselle River in the historical region of Lorraine in northeastern France. The leaf came to its present owner with few indications of its provenance and its character, apart from those which it carries upon its very surfaces — encumbered as they are, with both additions and extractions as well as the effects of heavy wear and tear.

So, learning the location of its recent point of departure as it made its debut (so far as we know) online helps somewhat in the quest to consider the transmission of the leaf across the centuries. But that knowledge does not take us necessarily very far, and it appears to present a seemingly impenetrable brick wall.

Remember, an assumption that a medieval manuscript or fragment would have been made and used near where it turns up — commercially, no less — in modern times can be rash. Not only because some finders and vendors might wish to hide the traces, but also because the manuscripts could, and sometimes demonstrably did, migrate from place to place, even widely, during the course of their history, medieval included. A forthcoming update for one of our blogposts will tell more about the travels of parts of an Aristotelian manuscript from different 14th-century centers in Eastern Europe, in “More Discoveries for ‘Ege Manuscript 51’.” Meanwhile, see its initial post: More Leaves from ‘Otto Ege Manuscript 51’.

The seller’s listing described the fragment simply thus:

Document médiéval sur parchemin

fin XIVème ( probablement vers 1380 )

En l’état, ayant certainement été utilisé comme reliure

Texte et région à découvrir…

However, a late 14th-century date is too late. The seller’s guess seems like a shot in the dark. Presumably it derives from a glance at the script and aspect, tout court (no exact equivalent in English for this French phrase), without any effort to identify the text or its “région”.

The seller’s statement that its condition indicates that the leaf had “certainly been used as binding” corresponds obviously enough with the current shape, having the impositions of secondary trimming and folds, mitered flap, added vellum ties, and pulpy portions of added endpapers. Plus the distinctive traces of wormholes that bored their way through boards, presumably made of wood. Interesting, isn’t it, how much can be seen in the remnants from the fuller form(s) of an earlier state? You could learn some more tips or tricks about such abilities in an illustrated essay about Physical Evidence and Manuscript Conservation: A Scholar’s Plea.

Strictly speaking, the phrasing of the vendor’s statement might imply that the fragment came into his hands already having been stripped of its innards comprising written materials of some kind. Those materials presumably comprised sheets of paper, not vellum, perhaps the same stock as the pulpy whitish remnants of the pastedowns and liner.

However, it is rarely certain that observers’ or sellers’ or cataloguers’ brief descriptions of artefacts placed in their presence display a full precision of terminology — unless, say, the specific agent defines the chosen terms clearly and/or we may check their terms against the thing itself in the same state. You can read my crisp observations about such situations and uncertainties, deserving to be taken firmly into account, in a study of a lost Anglo-Saxon textile: The Byrhtnoth Tapestry or Embroidery.

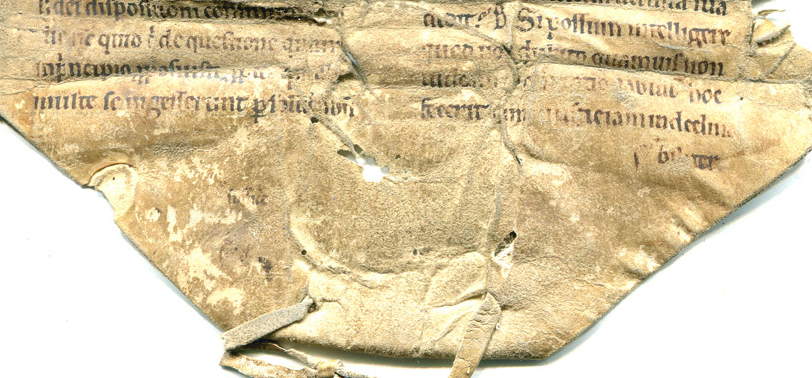

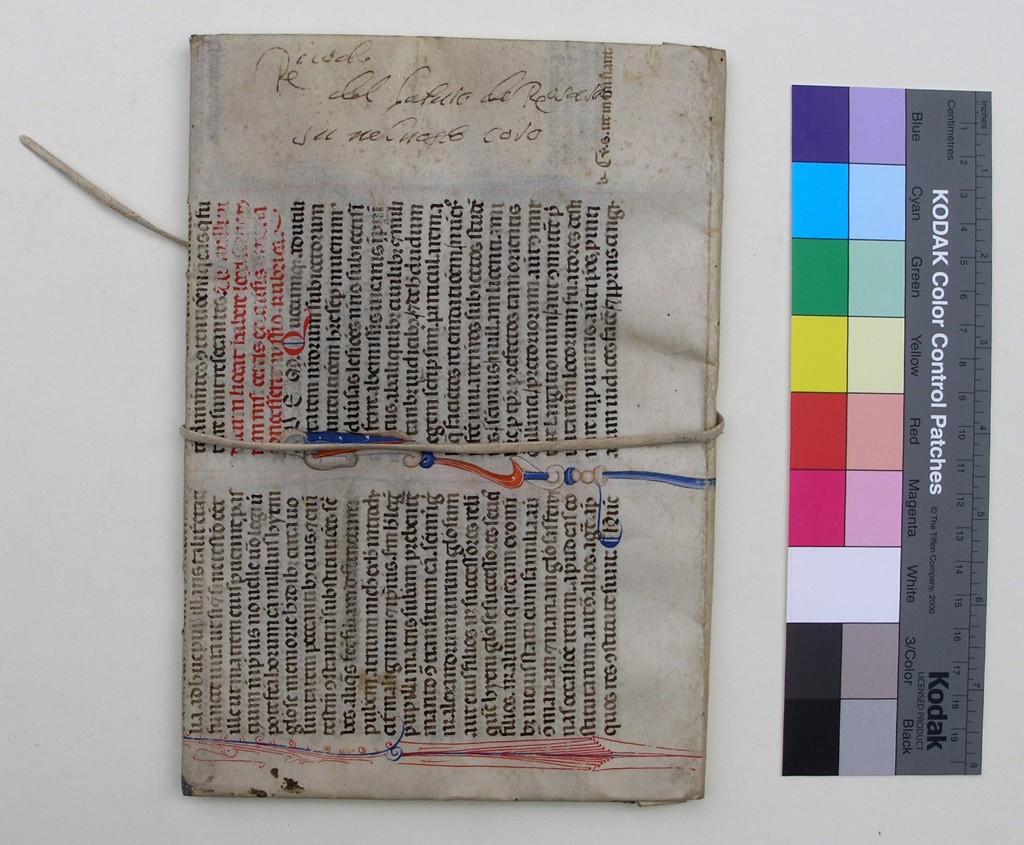

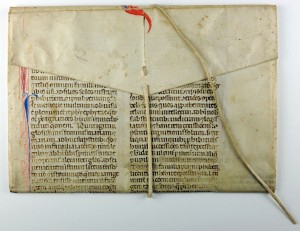

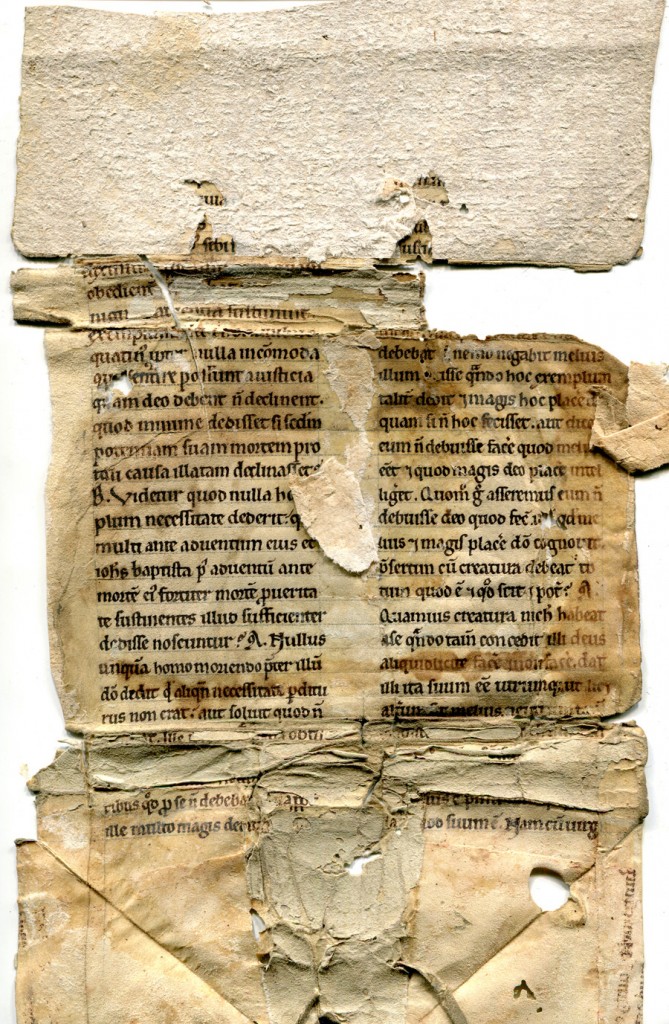

The Reuse

After removal from the former manuscript, the leaf was trimmed at the top and part of the sides. The original recto was turned outward, and so offered up to exposure, wear, and tear more than the enclosed interior. The corners of the lower margin were folded to form mitered turn-ins for a tapered flap, into which was laced a vellum thong for ties. Then came the stiffener, with pasted portions. Parts of those pastedowns have peeled or fallen away, exposing more parts of the script, along with the signs of wear, tear, wrinkles, and holes.

Verso of the Leaf and Interior of the Binding, Detail: Lower Right-Hand Corner, with the Mitered Flap Unfolded.

Remnants of several lines of modern arabic numerals and perhaps letters entered in ink at the top of the recto, but partly trimmed at their right-hand-side, stand in the original upper margin. Set at a right angle to the original text, they appear to record or calculate sums, presumably receipts.

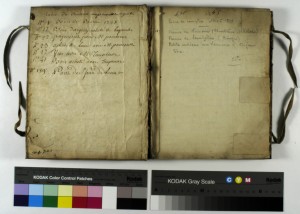

A Former State

Apart from its flap, the former state of the item may have somewhat resembled, say, the composite artefact reported in one of our blogposts, introducing Item Number 5 in my Illustrated Handlist. Seen, outspread, the outside and the inside of the gutted notebook show the reused medieval vellum cover, plus ties, and the paper interior, front pastedown and inner leaves included.

That item combines a medieval bifolium — removed more-or-less intact from a medium-format Vulgate Latin Psalter — and a modern paper notebook. The vellum bifolium remains in its reused state as the cover of the binding of an 18th-century paper notebook with with receipts in French, including some dated examples, extending from the mid-18th-century to 1809, with some of its portions removed and lost. The reused medieval bifolium, which presents 2 non-consecutive leaves of text, wraps around the pasteboards of the paper notebook. We call it a Cover-Up.

Another example in the same Illustrated Handlist and in our blog shows a mitred flap, plus tie, which conforms with the style of “our” fragment.

Handlist Number 7 represents a large-format double-column leaf on vellum containing part of the text of the Emperor Justinian’s “Novels” (as in Laws, not the fictional genre of prose narratives) removed from a decorated copy made at Bologna or Padua circa 1260–1280. After some reshaping, with folds and a mitered flap, plus an added tie, the unit served for some time as the folder for some written materials or other, now unknown. They were removed before the medieval portion was offered for sale on its own, in Italy. Only the added script in an originally blank area of the medieval leaf (a margin beside the columns of text) gives any suggestion about the former contents.

Guess what: In our blog, It’s A Wrap.

Now we focus on the Anselm fragment, which likewise found a second state in the service of enveloping some text(s) or other, presumably of a mundane nature. Quite a comedown, presumably, from its lofty original subject?

The Fragment of Text

“Our” fragment represents part of the text of the short, but significant, Cur Deus Homo? (“Why [Was or Is] God a Man?”), sometimes translated as Why God Became a Man. Its prolific author was one of the most influential among philosophical and theological thinkers of the high medieval period, and he held a major rôle in shaping scholasticism as a method of critical thought. Saint Anselm of Canterbury (1033–1109), archbishop of Canterbury from 1093 to 1109), composed this text during the period of 1094–1098. That is, it dates during his tenure as archbishop, but the composition was concluded specifically during the first of his 2 periods in exile, which occurred from October 1097 to 11oo; the second occurred from 1105 to 1107.

So prominent a figure in medieval theology, philosophy, and ecclesiastical history has many assessments introducing him and his achievements to the modern world.

The Author Anselm

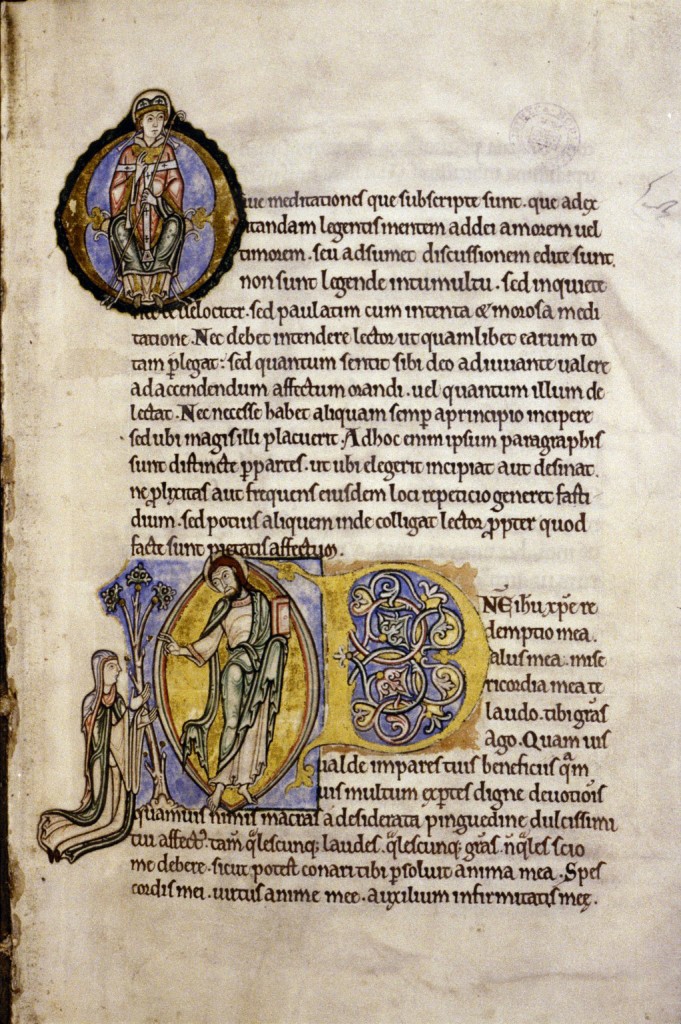

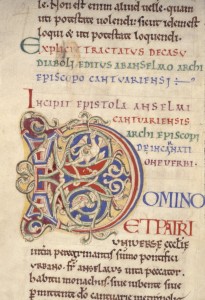

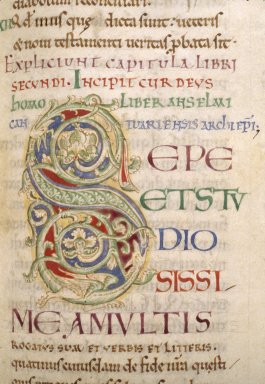

Bodleian Library, MS. Auct. D. 2. 6, folio 156r, Top. Opening of Anselm’s ‘Prayers and Meditations’. Photo: © Bodleian Library, University of Oxford.

Considering the nature of Anselm’s achievements and impact, we might take inspiration from the progression of long-term immersion in the subject by the distinguished Oxford historian R.W. Southern (1912–2001). For example, his study of Anselm’s development as author and thinker, which emerged first as Saint Anselm and his Biographer: A study of Monastic Life and Thought 1059 – c. 1130 (Cambridge, 1963), grew in rewritten form into Saint Anselm: A Portrait in a Landscape (Cambridge, 1990).

And now, for the simple purposes of introducing the “new” fragment from a copy of Anselm’s short text of monumental proportions, Cur Deus homo, we might think of the story of both the author and the treatise as A Portrait in Landscapes, travelling widely across time and place. “Our” little fragment itself has travelled no little in its voyage from the medieval world, already from within about a century of the composition of the text, into the modern, and from country to country and continent to continent.

Born at Aosta in Upper Burgundy (now in Italy), Anselm became a Benedictine monk at the age of 27 at the Abbey of Bec in Normandy. There he served as Abbot from 1078 to 1093.

View of the Abbey of Bec centered upon the Tour Saint-Nicolas. Photograph by Efcuse (2009) via Creative Commons.

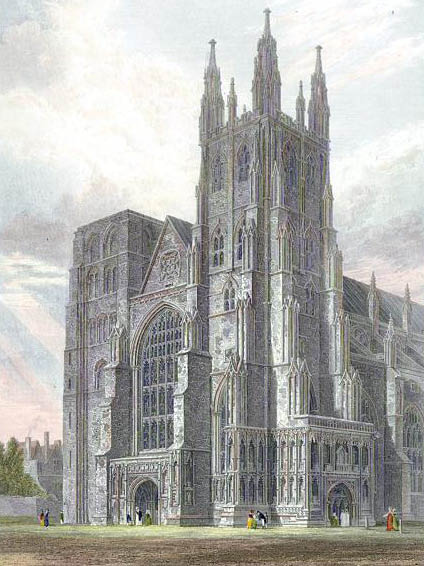

Next came the elevation to Archbishop of Canterbury, a position not without its ups and downs in the complicated relationship between Anselm and the English king, William II (circa 1056 – 1100, king from 1087). Consequently, Anselm did not reside for the full duration of his office within its metropolitan see and in command of Canterbury Cathedral. Although the structure of that edifice has changed over the centuries, not only decisively from the Anglo-Saxon to the Anglo-Norman periods, there remain above ground some traces of its aspect under the Norman archbishops, starting with Anselm’s predecessor Lanfranc.

A wistful interim view of the edifice appears in the Victorian image of the Cathedral published from a painting by George Cattermole in John Britton, The History and Antiquities of the Metropolitical Church of Canterbury: Illustrated by a Series of Engravings, of Views, Elevations, Plans, and Details of the Architecture of that Edifice, with Biographical Anecdotes of the Archibishops, Etc (London, 1821), page 125 (seen here). There we see the Western Towers of the Cathedral, prior to the rebuilding of the Northwest Tower.

Canterbury Cathedral, view of the Western Towers, engraved by John Le Keux after a picture by George Cattermole (published in 1821). Via Wikimedia.

In a curious way, disseminated at several removes through mass-production, this Victoria view on the ground from a different moment in its lonh history might resemble, or symbolize, the partly completed and ongoing reconstruction, sometimes lopsided, of the cathedral church at Canterbury — and for that matter of the English Church and Peoples as a whole under the Normans after their Conquest, by leaps and bounds since 1066 and beyond — which Anselm witnessed and helped to put into effect.

Location, Location, Location

During his first period of exile, Anselm competed Cur Deus Homo at the mountain village of Schiavi di Abruzzo in the province of Caserta in central Italy. We know more about the composition of the work, and its iterations, as well as its circumstances, than about many medieval works, even when their authors are known. How is that? He tells us. His Preface to it states:

propter quosdam qui, antequam perfectum et exquisitum esset, primas partes eius me nesciente sibi transcribebant, festinantius quam mihi opportunum est, ac ideo breuius quam uellem sum coactus ut potui consummare. . . . In magna enim tribulatione, . . . illud in Anglia rogatus incepi, et in Capuana prouincia peregrinus perfeci.

(“on account of some people who were making copies for themselves, without my knowledge, of the first parts of the work before it was complete or polished, I have been forced to make an end of it, as far as I could, more quickly than is convenient to me and more concisely than I wished. . . . At a time of great trouble . . . I began the work in England at another’s request and finished it as an exile in the province of Capua.”)

— Edition by Schmitt (1940), II, page 42; translation by Sharpe (2009), page 2 note 3 [For references, see below]

Fortunate we are that this author and his circle left specific testimony concerning some of the logistics as well as the intentions underlying the production and circulation of the written texts. The surviving manuscripts themselves may add eloquent, if elusive, elements to the story.

Text as Defining Attribute

So important is this text in the author’s oeuvre, its title was chosen for the cover of the closed book which the archbishop holds at his chest in his full-length statue in a prime position on the south face of the porch on the exterior of Canterbury Cathedral. There he stands among the four great Archbishops, Augustine, Lanfranc, Anselm, and Cranmer, and with many other worthies deemed appropriate for monumental depiction upon that edifice in the high Victorian period. The story of the Statues on the West Front of Canterbury Cathedral is revealing, with almost all of the 55 full-length figures in niches produced by Theodore John Baptiste Phyffers (circa 1820–1876), a Belgian sculptor resident and working in London.

Saint Anselm, Archbishop of Canterbury, carved in stone by Theodore Phyffers (1821-1876) on the exterior of Canterbury Cathedral.

Southwest Porch of Canterbury Cathedral, with niches filled by 1869 with sculptures by Theodore Pfyffers. Photography

(Views of the southwest porch with Anselm’s statue also formerly appeared via http://cranberrymorning.blogspot.com/2015/06/canterbury-cathedral-england-anglophile.html/.)

Words, Words, Words

The text of Cur Deus Homo is available freely online in several versions, mostly out-of-copyright, and also elsewhere in print. A few references, with links where available, demonstrate the range. The comments here chart a course through them, including those versions which provide vernacular translations for the Latin, or depend upon others’ editions not still in copyright and not necessarily dependable as records of Anselm’s rendition or the manuscript witnesses’ variants.

Latin Editions

Title Page for Anselm’s ‘Complete Works’ in Gabriel Gerberon’s edition as republished by J.-P. Migne. Via gallica.bnf.fr.

- Gabriel Gerberon, Sancti Anselmi ex Beccensi Abbate Cantuariensis Archiepiscopi Opera, nec non Eadmeri Monachi Cantuariensis (1675) and reprints, for example (1834)

- reprinted with many errors by Jacques Paul Migne for the second series of his Patrologia Latina (Paris 1844–1864, 221 volumes), as Vols. CLVIII & CLIX (1853–1854), with Cur Deus Homo in Volume 158 (1853), pages 39–133 (columns 0259C–0432B)

- issued online via Corpus Corporum: Repositorium operum Latinorum apud universitatem Turicensem in an interactive version based upon Migne (1853), using Classical Latin orthography, and with embedded dictionary links

- Hugh Laemmer, Cur Deus Homo (1857), via Google Books here

- Franciscus Salesius Schmitt, S. Anselmi Cantuariensis Archiepiscopi Opera Omnia (6 volumes, 1938–1961), Volume II, with the edition of Cur Deus homo at pages 37–133, rendered from seven 12th-century manuscripts (listed on page 38)

- printed despite interruptions; the complicated printing history of this edition, disrupted by war, is summarized by Sharpe (2009), page 2 note 3, wherein it is noted that, for example, some parts retain a title page with the formerly intended, rather than the actualized, place and date of publication

- presented online by subscription via InteLex Corporation (1998), with Volume II [“Edinburgh, 1946”], at pages 37–134, preserving the page divisions but not the printed line divisions with their numbers

- reprinted with Prologemena, Addenda, and Corrigenda, 2 volumes (1968)

In Translations

Bilingual Latin–French versions:

- Anselme de Cantorbéry, Pourquoi Dieu s’est fait homme. Sources Chrétiennes, 91: Série des Textes Monastiques d’Occident, 91, translated by René Roques (Paris, 1963)

- Michael Corbin and Alain Galonnier, L’œuvre d’Anselme de Cantorbéry (Paris, 9 volumes, 1986), III: Lettre sur l’incarnation du verbe pourquoi un Dieu-homme

English translations:

- Cur Deus Homo by St Anselm, to Which is Added a Selection from his Letters. The Ancient and Modern Library of Theological Literature (1889?, etc), by an anonymous translator, available via Online Books (ETWN) or via the Hathi Trust (with U.S. access only), for example (1899?) and (1909)

- Sidney Norton Deane, Cur Deus Homo (1903), also available via Sacred Texts and Online Library of Liberty, and unattributed in transcription here

- Jasper Hopkins and Herbert Richardson, editors and translators, Complete Philosophical and Theological Treatises of Anselm of Canterbury (2000)

And more:

- via Google Books

Bodleian Library, MS. Auct. D. 2. 6, folio 156r. Opening Page of Anselm’s ‘Prayers and Meditations’. Photo: © Bodleian Library, University of Oxford.

The Manuscript Transmission

The manuscript witnesses (63 recognized so far) to the text are listed conveniently online via Mirable: Digital Archives for Medieval Culture: Cur Deus homo , with links to lists of the contents for each of these witnesses, including other works by Anselm or other authors. Some contain the full text, while some only contain, or retain, portions of it or extracts from it.

The full corpus of medieval manuscript fragments of the text awaits attention, while more of them await recognition. Many factors — among others, the wide circulation of the text before the waning of interest in scholasticism as a subject and a way of thinking, many changes in religious habits after the medieval period, the drive to recycle old books deemed expendable, and the impulses of commercialism for distributing medieval written materials in recent centuries — conspire to ensure that more discoveries might increase the count.

“Our” fragment belongs in their company. The apparent date of the script, not yet ascribed to a particular center or scribe, places it among the group of “early witnesses” to Cur Deus homo.

The Early Witnesses

Nearly 45 manuscripts, at least, survive as 12th-century witnesses to the text. Mostly they contain more than one text, with Cur Deus Homo keeping company usually with another or other texts by Anselm. Instructive research on the composition, completion, and early transmission of this work is reported by:

- Thomas H. Bestul, “The Manuscript Tradition of Anselm’s Cur Deus Homo,” Studia Anselmiana, 128: Cur Deus Homo. Atti del Congresso Anselmiano Internazionale, Roma, 21–23 maggio 1998 (Rome, 1999), pages 285-307

- Ian Logan, “Ms. Bodley 271: Establishing the Anselmian Canon?”, The Saint Anselm Journal, 2.1 (Fall 2004), 67-80, available as .pdf

- Richard Sharpe, “Anselm as Author: Publishing in the Late Eleventh Century,” Journal of Medieval Latin, 19 (2009), 1-87, online with subscription here

D for ‘Domino’: Opening of Anselm’s ‘Letters’. Bodleian Library, MS. 271, folio 62v, detail. Photo: © Bodleian Library, University of Oxford.

Bestul’s Appendix (pages 304–307) includes a pair of lists of 12th-century manuscripts (pages 304–305), subdivided into those “used in Schmitt’s edition” and “other” 12th-century cases, numbering respectively 7 and 36 manuscripts, for a total of 43 witnesses. Fragments and cases as yet unidentified (or perhaps awaiting an earlier dating for their scripts) would bring the total higher.

Sharpe’s Table 1.A and 1.B (pages 80–85) identifies some “Early Booklets of Anselm’s Works”. They include those copies with Cur Deus homo either on its own or in company with other works, sometimes as separate booklets, that is, as distinct units which circulated alone or came to join company in composite volumes.

Some of the 12th-century witnesses can be viewed online. A notable example:

- Cambridge, Trinity College, MS B.1.37 (35), folios 1–26, made circa 1086 × 1100, probably circa 1093, from Salisbury Cathedral

Some have received descriptions ranging from concise reports to detailed analysis. Examples:

- Copenhagen, Det Kongelige Bibliotek, MS GKS 3394 8°, made perhaps ca. 1140–1190 and owned by the Benedictine monastery of Saints Cosmas, Damianus and Simeon in Liesborn in Germany

- Oxford, Bodleian Library, Bodley MS 271 (Summary Catalogue, number 1938, online here), made circa 1100–1140 at Christ Church, Canterbury; with a few images online, a conservation report for Early Anselm Manuscripts in Oxford, and the detailed account by Logan (2009)

Initial S for ‘Sepe’. Bodleian Library, MS 271, folio 127v, detail. Opening of Anselm’s ‘Cur Deus Homo’. Photo: © Bodleian Library, University of Oxford.

The Dialogue in 2 Books

In 2 Books containing respectively 25 and 20 chapters, the text takes the form of a dialogue between Anselm and his student Boso, a monk at Bec, who had asked Anselm to write on the subject.

It perhaps goes without saying (but we’ll say so anyway) that Anselm’s parts not infrequently extend for some length, with shorter questions, responses, and reflections by Boso. The Cast: Star of the Show, plus Acolyte.

Later, Boso was abbot at Bec from 1124 to 1136, where Anselm had served as abbot. They corresponded extensively, as shown by surviving letters preserved mainly in collections of Anselm’s works. Boso’s rôle as “Anselm’s foil in perhaps his most famous work Cur Deus Homo“, begun in England in 1094 and completed in exile in 1098, finds a spirited justification in an earnestly whimsical letter from George E. Brinkerhoff III of Quoque, Long Island, to the New York Times, headed by the byline “The First Bozo Probably Wasn’t a Clown” (16 August 1991).

Like many medieval works, it [the treatise] is in dialogue form; Boso asks the questions, and Anselm provides the answers. The progress of the argument demands that Boso be continually mistaken and corrected. Boso is the dummy, often obtuse, allowing Anselm to chide him, defeat his views and continue in a teacher-to-student relation. While scholastic theology may seem dry and lifeless to us now, it was thrilling stuff to the intelligentsia of the day, both life-affirming and life-threatening.

No doubt many a slow-witted monk was called “Boso” by his fellows as Anselm’s influence on Christian thought increased.

While the onomastics remain questionable (in fine scholastic fettle), this explanation makes for a good story.

Text in 2 Parts

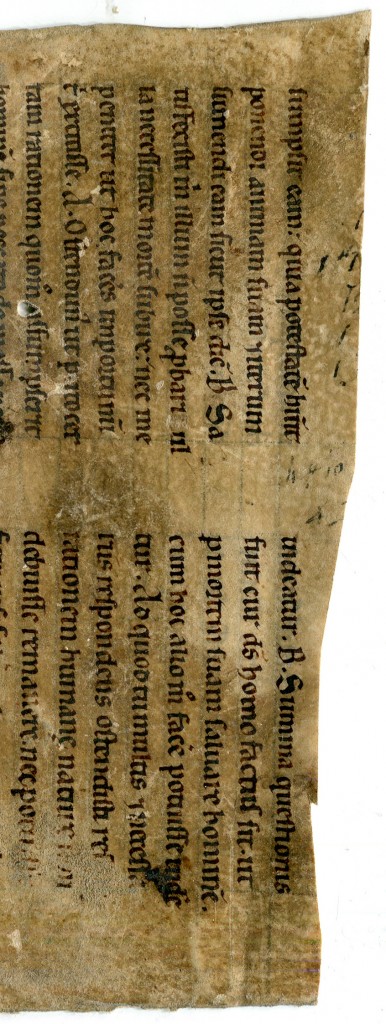

Like many manuscript witnesses, “our” fragment places the names of the 2 speakers at the head of their respective sections. Similar treatment pertains to other texts in dialogue form. For example, it navigates a path through the Dialogues of Gregory the Great, in which Gregory and his disciple Peter converse, with the master relating the stories of inspirational holy men and the disciple responding with questions, observations, and formulations of the moral of the stories, all the better to showcase the insights of the great man. Some posts in our blog illustrate examples from that text, as with A New Leaf from ‘Otto Ege Manuscript 41’.

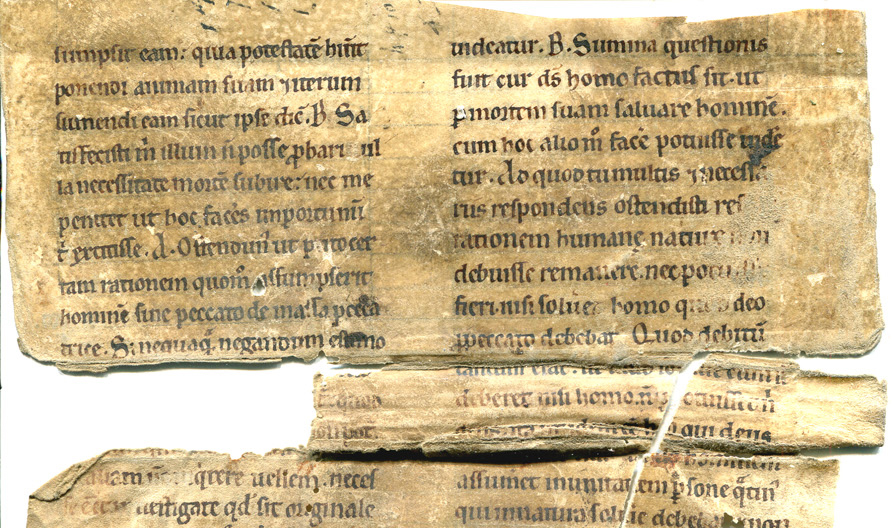

On “our” fragment, as in some other early witnesses (such as the Trinity College Cambridge example), the names of the speakers are abbreviated by their initial (“A” and “B”). Further saving space, the parts of these 2 voices in the dialogue fill the lines by running consecutively from one to the next within the lines, with the next speaker’s part beginning directly following the end of the former’s.

Set within the line, the speaker’s Initial introduces his section with a somewhat higher form than the raised initial of his opening word. That Initial is distinguished by means of one or two lowset dots, much as medieval practice would set off roman numerals from the body of the text employing similar letter-forms customarily by a dot or a pair of dots.

Here, the identifying Initial for each Speaker’s Part is, by turns, accompanied by a single lowset dot or flanked by a pair of dots. For example, at the top of the recto, the B stands within line 3 of column a (= line “ra3”)and line 1 of column b (line rb1), while A stands within line ra7. Each Initial stands beside the punctuating dot which concludes the preceding part and thereby doubles as distinguishing dot for the Initial. A similar dot follows the Initials in lines ra7 and rb1, while the B in line ra3 has none, so that the punctuating dot and the elevated height of the letter must suffice as a recognition sign.

Patterns of Transmission

The manuscript witnesses demonstrate a circulation of the text, already early in its existence, on its own as a small book or booklet or in company of other works, by Anselm or sometimes by others. “Our” witness, so long as it is known only by this fragmentary leaf, does not appear to demonstrate which case pertained for its manuscript.

Other cases, including early witnesses, reveal their characteristics by several ways, even when they now stand alone or in fragments. For example, according to its online description, the Copenhagen copy of the text (MS GKS 3394 8° of circa 1140–1190) was produced as a unit of its own, as “confirmed by the numbers in the lower margin of the last page of each of the first seven quires, by the excision of two superfluous leaves in the last quire, and by the incipit and explicit of the book.” Its numbers and “captions” for the chapters (25 chapters of Book I and 20 chapters of Book II) are written out on 3 pages at the front (folios 1v–2v), then “repeated in the margin at the beginning of each chapter. Its rubrics refer to Anselm’s work successively as a liber (folio 1r), an opus (folios 1r, 1v), and an opusculum (folios 2v, 62r), that is, as a “book”, a “work”, and a “little work”.

Although the absence of a chapter number-plus-caption (or title) on “our” leaf could align its version of the text with those which do not apply a new chapter division between chapters 17/18 or 17/18a (or the like), its approach might merely mean that rubrications or marginal insertions signalling such divisions never reached completion, unlike, say, the Copenhagen copy. Further discoveries might settle the question for “our” copy. Meanwhile, the known patterns of transmission of Cur Deus Homo in the early manuscript witnesses could easily be described as treating it variously as a “book”, “work, and “little work”, brief and to the point.

The Fragment

The course of the original text establishes which side was the recto, which the verso. The portion on the fragment represents part of 1 or 2 chapters near the end of Book II, depending upon the numbering systems adopted by different editions.

- chapters 17 and 18, as in Schmitt (1940), Roques (1963), and Corbin and Galonnier (1988)

- chapters 18/17 – 19/18, as in the Corpus Corporum version

- chapters 18a and 18b, as in the unattributed version via Wikisource

These differences seem to reflect the different approaches in the manuscripts. As observed by Bestul (1999), page 287, “there is considerable variation in the early manuscripts where the chapters divide”. Thus, “our” witness takes its stand among those variations.

Laid out in double columns of 35 lines, the text flows without fanfare in rb29–30 from chapter to chapter (or between sub-chapters), without a chapter title or enhanced opening for the succeeding one.

The recto commences mid-phrase with [et iterum /] sumpsit eam: quia potestatem habuit and continues to et iusticiam indeclina-/biliter with a run-over into the lower margin completing the word. This span corresponds to the printed version from Laemmer’s page 158 line 13 to page 161 line 6, or Schmitt’s page 126 line 1 (close to the end of Anselm’s long portion) to page 127 line 13 (within Boso’s portion).

The first lines of the verso are mostly covered by the pasted pulpy fibers of the stiffener employed in the secondary use of the leaf as a limp cover with flap closure. The text extends there to Nam cum uirg[/initatis melior], breaking off mid-word. This span ends within Laemmer’s page 164, line 23. Provided the text in the manuscript corresponded with the printed edition(s), we might expect the preceding leaf to have ended with the words et iterum, and the following leaf to have begun with –initatis melior.

According to the customary titles (or captions) for the chapters, the 2 chapters or sub-chapters represented on the fragment belong to those which consider these subjects:

- Chapter 17/18/18a

Quid in Deo non sit necessitas, vel impossibilitas: et quid sit necessitas coens, et necessitas non cogens

“How, with God there is neither necessity nor impossibility, and what is a coercive necessity, and what one that is not so”

2. Chapter 18/18a/19

Quomodo vita Christi solvatur Deo pro peccatis hominum; et quomodo Christus debuit et non debuit pati

“How Christ’s life is paid to God for the sins of men, and in what sense Christ ought, and in what sense he ought not, or was not bound, to suffer”

Without such headings or numberings, the reader must plow through the dense mass of text as such, while the Speakers’ Initials form pausing points of orientation through the texture of discourse.

Date and Place of Origin

Setting the fragment in its place among the manuscript witnesses to Anselm’s text may go hand in hand with identifying its origin and its former manuscript. Further work may reveal more closely what scribe, center, and manuscript exemplar worked together to create this copy.

Now that it shows its face and features in this blog, “our” fragment of a leaf which stood close to the end of Book II of Cur Deus Homo might find some pointers toward its larger setting. This setting — a landscape, shall we say — encompasses the excited early stages across Europe of receiving and transmitting Anselm’s “little book” on a big subject. Those stages, and that wide landscape, made it possible to hand it on (and hand it over) to more readers in various centers, not only in that early period of the history of the text, but also long afterward, even if in fragments attesting to larger patterns of transmission, largely or mostly lost and dispersed in the upheavals of history.

*****

We thank the owner of the fragment for permission to study, reproduce, and publish it. Do you know of other parts of the same original manuscript or works by the same scribe? Do you have suggestions for the date of origin and place of origin for a 12th-century fragment of Anselm’s ‘Cur Deus Homo’?

Please let us know!

*****

I like the helpful information you provide in your articles. I’ll bookmark your weblog and check again here frequently. I am quite sure I’ll learn many new stuff right here! Best of luck for the next!