Cover-Up

June 17, 2016 in Manuscript Studies, Photographic Exhibition

A Medieval Bifolium

From a Medium-Format Vulgate Latin Psalter

Reused as the Cover

of the Binding

of an 18th-Century Paper Notebook

With Receipts in French

Budny Handlist 5

Continuing our reports of discoveries about manuscripts and written materials in our blog on Manuscript Studies,

Mildred Budny examines a reused medieval fragment in its reused state, still attached to its modern notebook containing many receipts in French.

Exhibit: Layered Take

Medieval to Modern

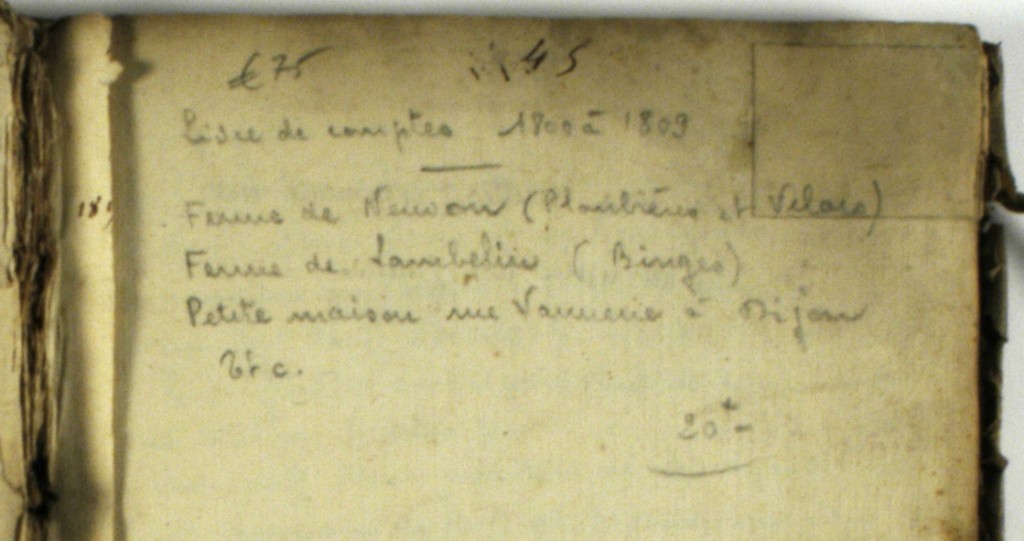

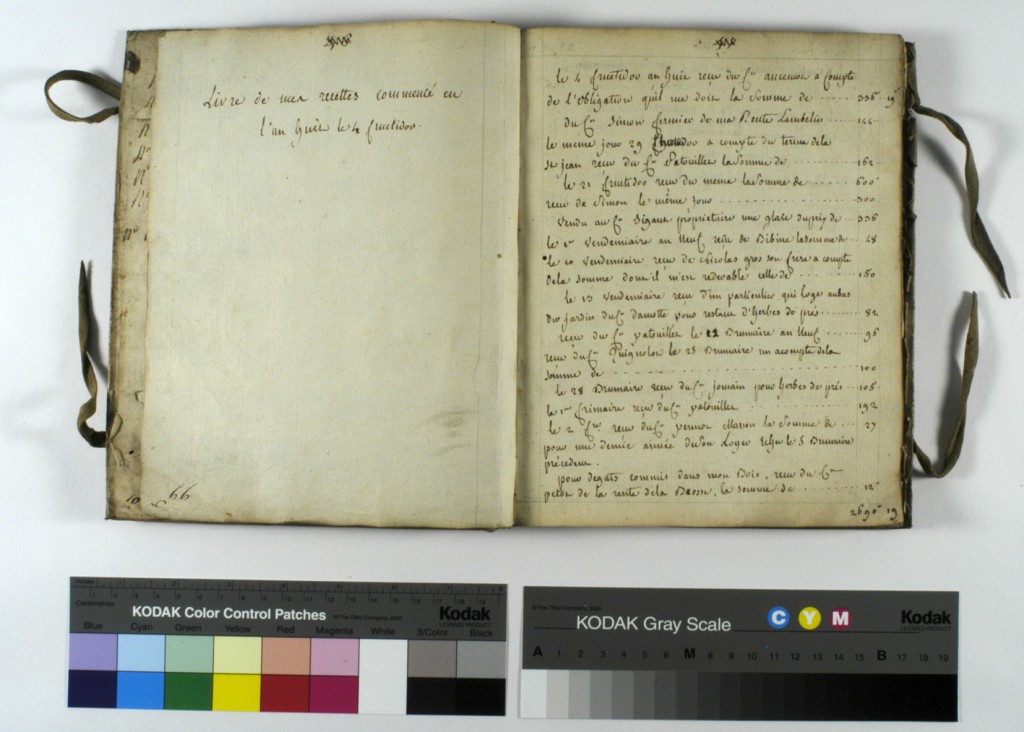

Our take today: a fragmentary parchment bifolium reused as the covering for the front and back pasteboards of a notebook of paper leaves containing various texts — and many blank leaves. Their texts at present begin with a Liste de comptes 1800 à 1809, as described in the contents list inscribed in pencil on the recto of the first surviving leaf — now numbered 45. The losses of 44 leaves, at least, make it difficult (to put it mildly) to determine the starting date for the reuse of the medieval bifolium and the use of the paper notebook.

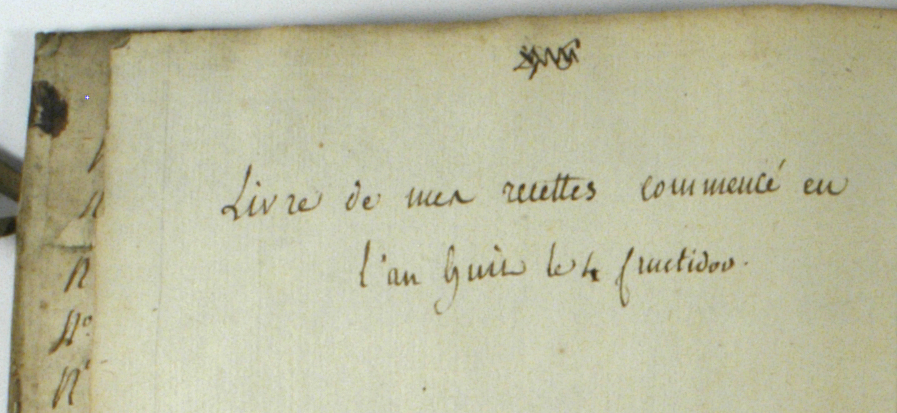

The first text (folios 45v onward) has the title Livre de mes recettes commence en l’an huit le fructidor. Year VIII, Month Fructidor. The title is inscribed in ink on the verso of that endleaf. In the French republican calendar, Year VIII corresponds to the span of 23 September 1799 – 22 September 1800, while the month of Fructidor (named from the Latin fructus, ‘fruit’) in that particular year extended from 19 August to 17 September. The inscription in the first person indicates a specific, personal touch.

The ink pagination intermittently at the top center of the paper leaves now ends with number ‘186’ on the last verso. Both the re-numberings of the pagination and the stubs of excised leaves at the front of the volume demonstrate that originally the book was larger and presumably had other texts at its front. The paper paste-downs at both front and back carry entries in pencil and pen. The cover retains its pair of leather ties. A fuller study might yield better information about the purposes and uses of the notebook.

The composite Handlist 5 comprises Part A and Part B, respectively medieval and modern. According to the owner’s recollection, this volume was acquired in France, probably by purchase, between circa 1999 and 2007, when I first saw and photographed it. My enquiries about the recent provenance extended across several years as I conserved, photographed, and researched the assembly of materials in the Handlist as it grew and transformed.

In this composite entity acquired in France, at least the modern Part was produced in France, and perhaps also the medieval Part.

The Medieval Layer

Part A is a reused vellum bifolium, or double-page spread, from a religious medieval manuscript; its span of text presents discontinuous parts of the Psalms in Latin. It found reuse in the modern period as the exterior wrapping for the cardboard covers of a paper notebook (Part B). Partly despoiled, or censored, the notebook contains receipts in French pertaining at least in part to Dijon and its region. With some leaves removed, the extant receipts begin during the French Revolution and continue until partway into the Napoleonic Wars.

The artefact remains composite, with the reused medieval leaf still in situ. There seems no pressing reason to remove that bifolium from its Afterlife, and so, in extended conversations, its owner and the consultant/conservator/photographer/researcher (Yours Truly) decided to leave it As Is, as a monument in its own complicated terms.

Parts of the Whole

I. The Medieval Layer

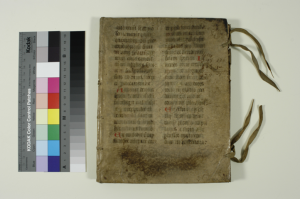

Part A. Bifolium from a Medium-Format Vulgate Latin Psalter or Breviary

= Unnumbered folios ‘I’/’II’ now forming the exterior skin of the front and back covers

Parts of Psalm 77 on Leaf I and Psalm 88 on Leaf II

Medieval Bifolium (Folios I/II)

Visible span circa 380 × 226 mm, plus hidden turn-ins on all sides

< written area circa 160 × 124 mm >

Double columns of 19 lines

with inset 1-line initials in red pigment

Perhaps Southern France, late 13th or early 14th century

Reused, and still in situ, as the cover for the pasteboards of an early modern paper notebook (partly despoiled) with accounts in French = Part B. The original fold line of the medieval bifolium, with its original stitching holes, lies more-or-less centered at the spine of the new volume.

II. The Modern Layers

Part B. Paper Notebook for ‘Recettes’ Etc.

Notebook now of 99 paper leaves (with some first leaves removed), plus paper pastedowns at both front and back,

employing the medieval vellum bifolium of Part A as the ‘leather’ covering for the pasteboards of its binding, plus two pairs of added leather ties (presumably 18th-century)

Various texts in sections written in ink mostly in the late 18th – early 19th centuries, with some blank leaves and with a set of entries in pencil by a single bookseller’s hand in the late 20th or early 21st century on folio ‘1’r (as counted at present)

Paper Notebook circa 226 × 178 × 27 mm

< written area variable >

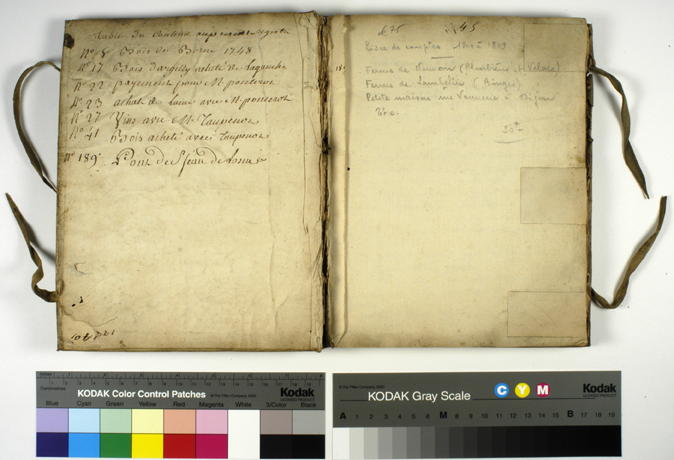

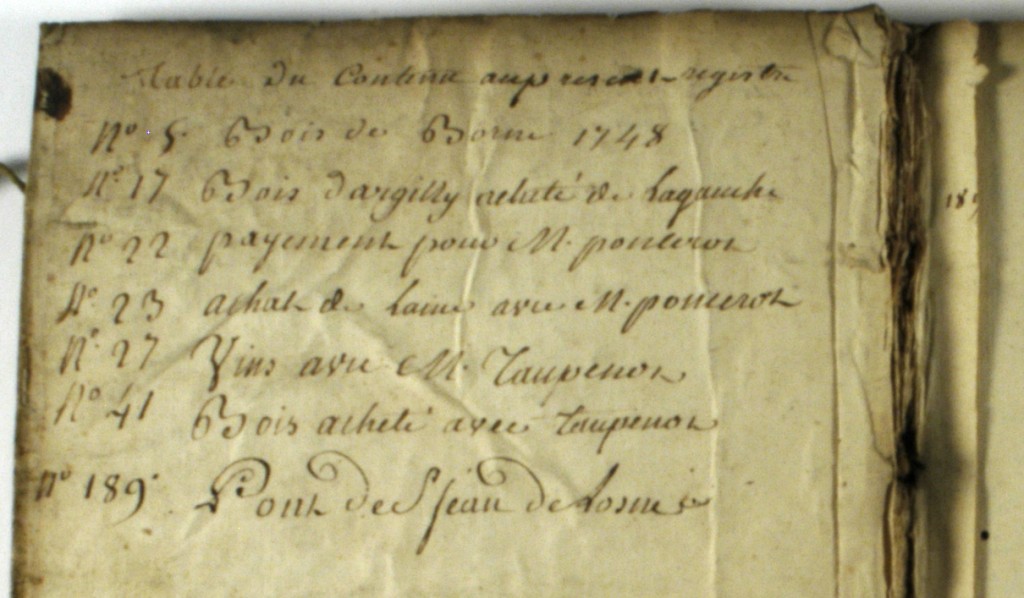

Table du contenu on front endpaper

for items numbered 8, 17, 22, 23, 27, 189 [all removed]

Seller’s inventory in pencil on first page for folios ’45’ onward,

with an incomplete Liste de comptes 1800 á 1809

France, mid-18th century and later, in and for Dijon and its region

The Inside Front Cover

Headed Table du Contenu au paiment[?] registre, (‘Table of Contents for the register of payments[?]’), the first itemized List on the inside front cover records only Numbers 8, 17, 22, 23, 27, 41, and 189. Mostly the items concern Bois (‘wood’), usually specified as comprising purchases, and sometimes with the seller’s names. We might wonder — especially because those pages have been excised and, apparently, lost — what the other unlisted Numbers concerned, as well as what the listed Numbers related.

View of the River Saône at Saint-Jean-de-Losne in Burgundy. Photograph by Christophe Finot via Wikipedia Commons.

The list begins with Bois de Borne (No. 8). To its lower right hovers the number, or year, 1748, written in somewhat lighter ink and at different sitting, apparently by the same hand.

The next items register purchases of Bois d’Argilly — communal wood pertaining to the inhabitants of Argilly and elsewhere in the Côte-d-Or — from a seller named Lagrande (No. 17), wool from Monsieur Pomerol (No. 23), and wines and wood from Monsieur Tapenon (Nos. 27 and 41); and a payement (‘payment’) for Monsieur Pomerol (No. 22) directly preceding the record of the wool purchase from him, maybe for that purchase or some other earlier one(s). The final item names Pont de Saint-Jean-de-Losne (No. 189), referring to the (or a) bridge in Saint-Jean-de-Losne, also in the Côte-d-Or. At least the selected list gives some sense of the locations and forms of transactions for some of the many Numbers which the excised leaves (folios 1–44?) at the front of the Notebook represented.

Number 189 and Counting

Opposite this pastedown — which would have been less easy to remove from the book than leaves standing free — there survives one stub from the cluster or quires of paper leaves which formerly stood at the front of the book, all before the first surviving leaf. We might consider the surviving first leaf to be folio ‘1’, now numbered 45, but that number 45 was altered from some earlier version, by changes made in ink at the top center of the recto. So let’s stick with folio ‘1’ for the survivor, which gives a fresh, Revolutionary, start for the extant group of leaves in the Notebook.

Partway down from the top on the recto of this stub (opposite Item No. 17 on the pastedown), there appears most of the number 189, partly trimmed at the right where the rest of its leaf was severed at knifepoint. The intervening leaves were removed completely, exposing the inside spine of the volume.

Although somewhat smaller in size than the numbers in the itemized List, this number closely resembles the color of their ink and the forms of the number 189. The survival of these features appear to indicate that the List relates to the full (or almost entirely full) series of lost items from the front of the book — although its Numbers imply that there were many more items between those which the List records. It remains possible that, depending upon the length of its entry, Number 189 may have been followed by one or more items on its leaf. This leaf was manifestly last in the series pertaining to its List.

There seems little way of knowing what were all the contents on the leaves removed from the notebook. Their nature might reveal why – and those reasons could be worthy of a novel. The scale and eloquence of the story remain to be seen.

Meanwhile, we might consider what remains.

Receipts, Dates, Locations

2 Farms and 1 House

The entries deemed worthy of note by the seller, before giving up (‘Etc’ . . . ), are 2 farms and a ‘small house’:

- Ferme de Nevour (Plancherine et Valois), in Savoie

- Ferme de Lambelise (Birges/Bourges)

- Petite maison rue Vannerie à Dijon (1200 Dijon), in Burgundy

— a street running between the place Saint-Michel and the Rue Dietsch (map here) - Etc.

The Month of Fructidor in Year VIII = 1799–1800 Depending

The next opening (folios ‘1’v –’2’r) commences the Livre de mes recettes, entitled on the verso and launched on the recto with a detailed list. That this set of entries represents a re-start of the use of the notebook appears from the missing leaves at the front of the book and the inverted folio number 99 in the lower left-hand corner of the verso here.

The next opening (folios ‘1’v –’2’r) commences the Livre de mes recettes, entitled on the verso and launched on the recto with a detailed list. That this set of entries represents a re-start of the use of the notebook appears from the missing leaves at the front of the book and the inverted folio number 99 in the lower left-hand corner of the verso here.

The crossed out running ‘titles’ on the opening have another part in the complicated story of the multiple entries and re-arrangements in the life, or perhaps multiple lives, of the notebook. At various points, the orientations of the different entries upon a single page or opening demonstrate that the notebook was handled, opened, and put to use, by turns with the front of the medieval bifolium as the ‘front cover’, upright like its text, and with the back as the point of departure, placing the medieval text upside-down.

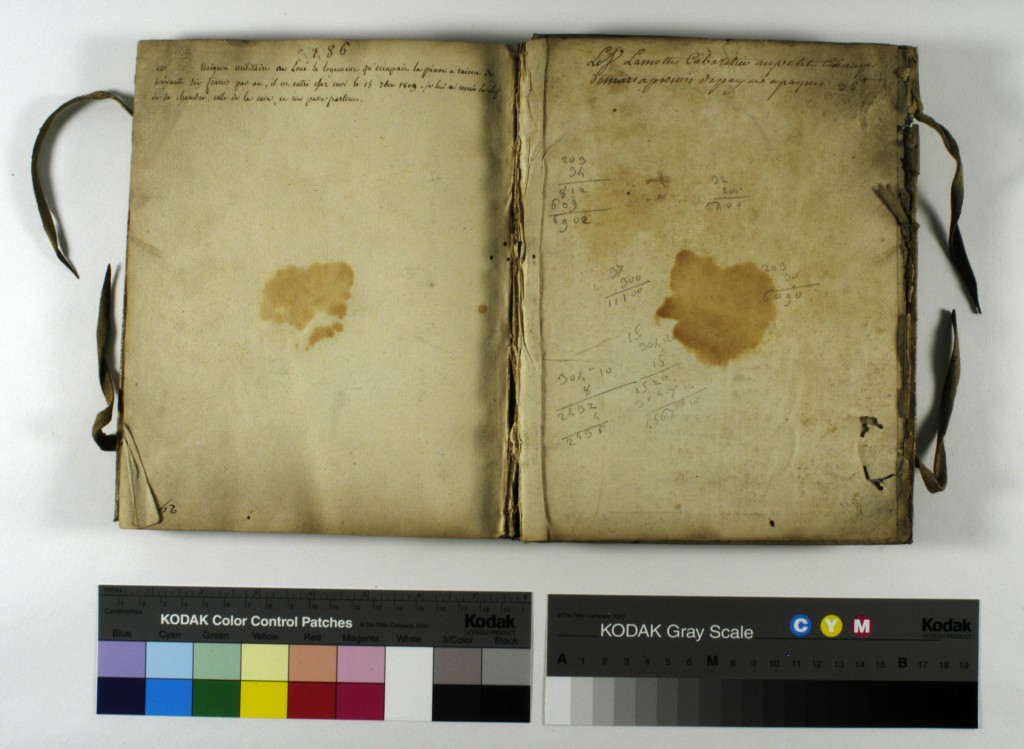

The End = 15 September 1809 and Counting

The last opening of the volume presents the centered (and altered) page number 186 over a single 3-line entry in brown ink on the last verso, and a 2-line entry in brown ink at the top of the unnumbered back endpaper.

The entry on the back pastedown states something like this:

M[? or S?] Lamotte Cabaritice au petit Chauq.. demors as promis de payer a payeur 96 [superscript unit].

That is, Monsieur? Le Seigneur? Whatever his status, this named male individual ‘Lamotte Cabaritce upon his death (de mors) has promised to pay 96 [something]’.

Identifying the individual might aid the date-range for the transaction. Perhaps it would extend the date-span for the Notebook.

The entry on the last verso now preceding that pastedown states something like this:

??? militaire a loue le logement qu’occupait le pinot[?] a raison de soixante dix[?] francs ??? au, il a entre chez moi le 15 7bre 1809. Je lui ai mis la clef de la chamber, celle de la cave, et un palle[?] partout.

According to the entry, the recorded date of commencement of remunerated lodging, in exchange for some 70 francs, by a specific (perhaps unnamed) military man within the domain of the First-Person Landlord (chez moi) was 15 September 1809. This is the last extant date in the Notebook. Its register suffices to demonstrate that the date-range of recorded transactions, insofar as they survive in the dismembered Notebook, extend from the start of the first series itemized on the front endpaper (and subsequently lost), and/or from the commencement in Fructidor of Year 8 of the first surviving set, to the Napoleonic Wars by the end of the surviving leaves.

Useful, and poignant, to recognize, that the 21st Legion of the Gendarmarie Impériale was headquartered at Dijon after 1804. Perhaps the first word of the entry represents an awkward conflation of Un+legion = Unigion. Or igien might represent a shortened version of Ingénieur, also a rank in the French army.

Who knows, detailed exploration among the (or some) archives may reveal who from that cadre was lodged where, somewhere in Dijon or its region, from the 15th of the 7th Month (September in the restored calendar) of the year 1809 (restored calendar). Until when?

Mostly the Recettes etc occur in brown ink. A few sums or multiplications, as on the inside back pastedown in various orientations by a single hand probably at a single sitting, are in pencil.

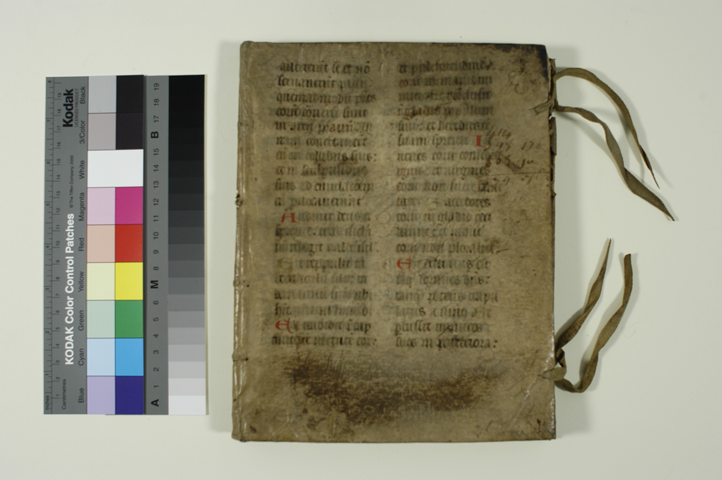

Up Front: Back to the Middle

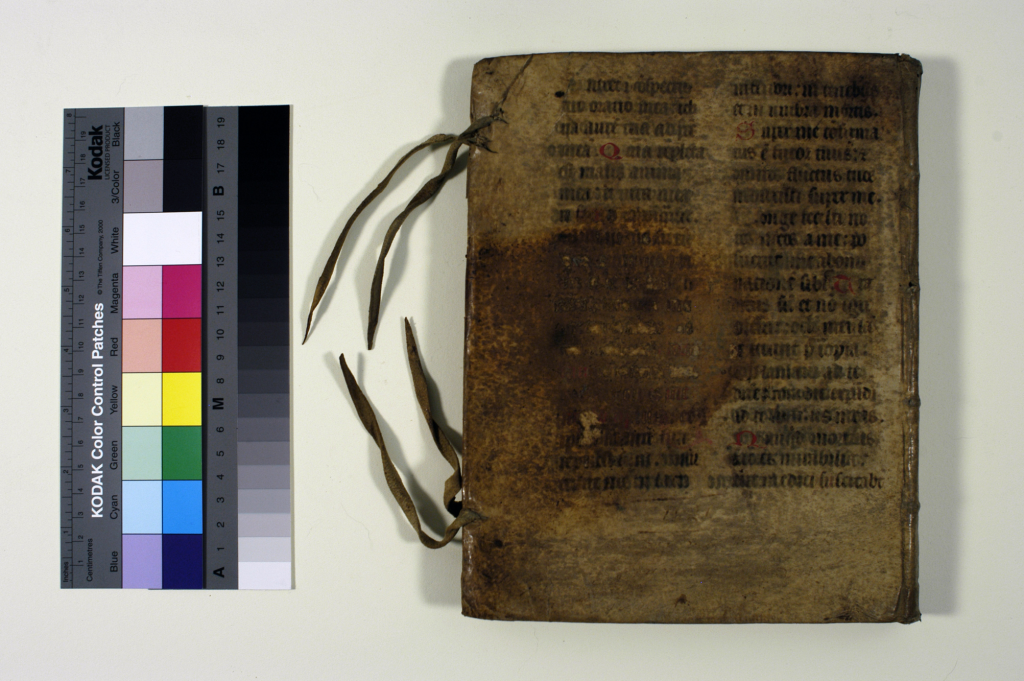

The front cover of the notebook presents the first recto of the medieval bifolium, which carries some added sums in brown ink along the fore-edge, relating to the reuse of the item as part of the composite notebook.

Back Up Plan

The back cover presents the last verso of the medieval bifolium in a state much more damaged through exposure, wear and tear, and rust-burn marks than the first recto on the front cover.

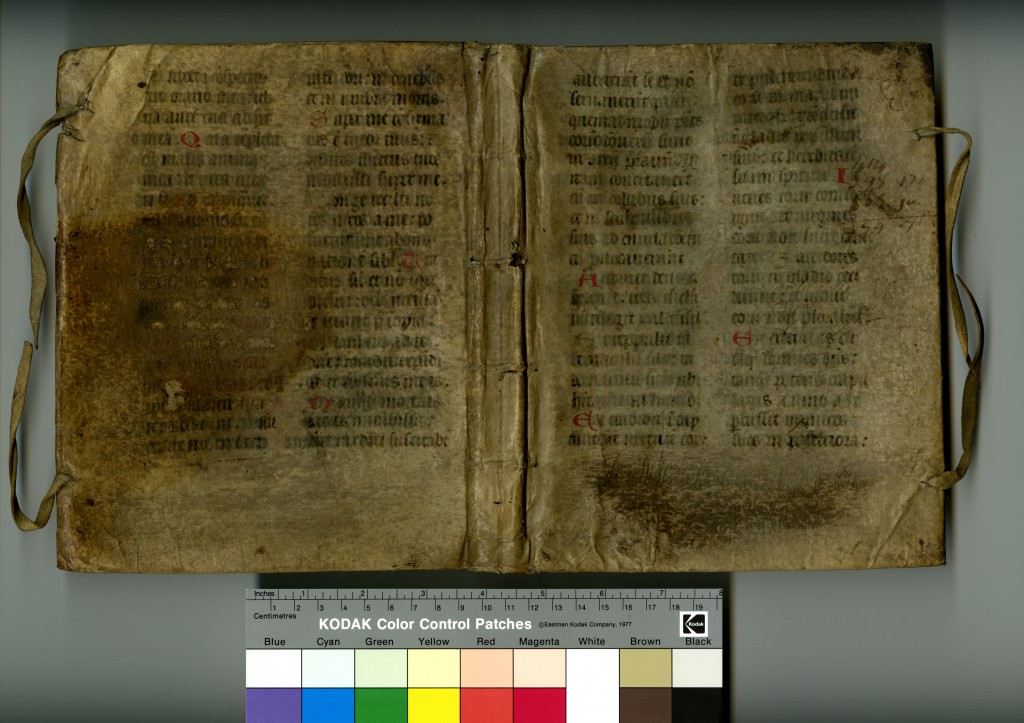

Open Up: Double Spread

Viewing the unit from the outside, with the outspread back cover, spine, and front cover (plus ties) of the binding, it is possible to see the full exposed extent of the outside of the medieval bifolium, whereby its original fold-line or gutter runs down the center of the spine of the paper volume. The spread reveals Folio IIv / Ir, with the first leaf of the original bifolium pressed into service over the front cover and the second leaf pressed against the back cover.

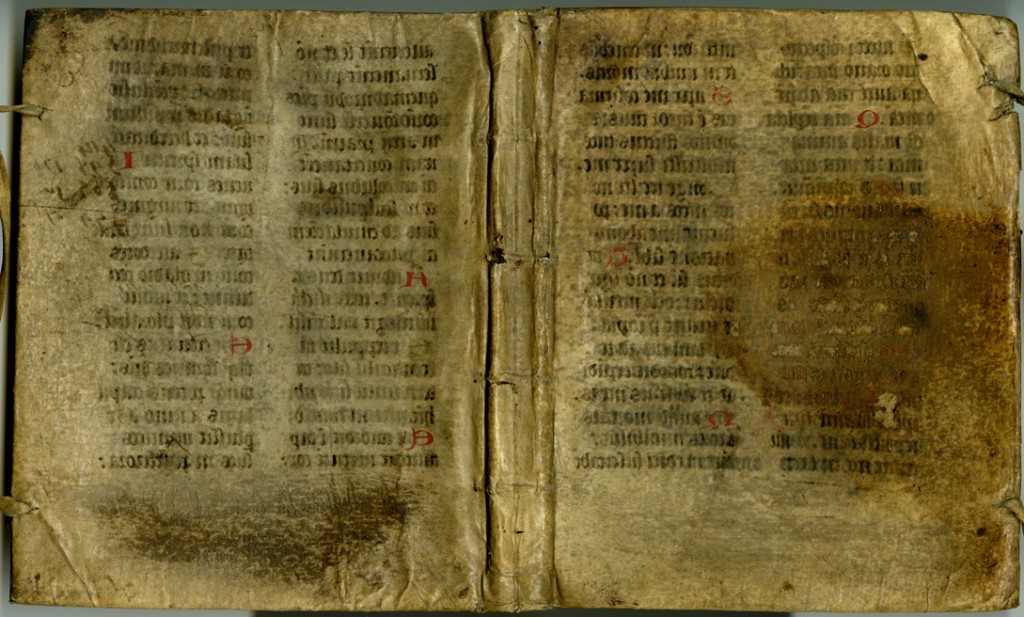

Back Up Plan: The Flip Side

Flipping the image horizontally, and enhancing it somewhat, offers a glimpse, right-way-around, of what appears on the inside of the bifolium — minus, that is, the text and initials on the outside.

*****

A Reused Bifolium from a Vulgate Psalter

Reused as

the Cover of the Binding

on an 18th-Century Notebook

Continuing our reports of discoveries about manuscripts and written materials in our blog on Manuscript Studies,

Mildred Budny showcases a reused medieval fragment in its reused state, still attached to its modern notebook with receipts in French.

A fragmentary parchment bifolium reused as the covering for the front and back pasteboards of a notebook of paper leaves containing various texts (and many blank leaves). Their texts at present begin with a Liste de comptes 1800 à 1809, as described in the seller’s contents list inscribed in pencil on the recto of the first surviving leaf — now numbered 45. The losses of 44 leaves, at least, make it difficult (to put it mildly) to determine the starting date for the reuse of the medieval bifolium and the use of the paper notebook.

The first text, beginning on the next opening (folios 45v onward), has the title Livre de mes recettes commence en l’an huit le fructidor. Year VIII, Month Fructidor. The title is inscribed in ink on the verso of that endleaf. In the French republican calendar, Year VIII corresponds to the span of 23 September 1799 – 22 September 1800, while the month of Fructidor (named from the Latin fructus, ‘fruit’) in that particular year extended from 19 August to 17 September. The inscription in the first person indicates a specific, personal touch.

The ink pagination intermittently at the top center of the paper leaves now ends with number ‘186’ on the last verso. Both the re-numberings of the pagination and the stubs of excised leaves at the front of the volume demonstrate that originally the book was larger and had other texts at its front. The paper paste-downs at both front and back carry entries in pencil and pen. The cover retains its pair of leather ties added to the ensemble at the time of its manufacture. A fuller study might yield better information about the purposes and uses of the notebook.

The Medieval Layer

The reused medieval bifolium has double columns of 19 lines of text, written in Latin in an upright and rather stately Gothic script. At the beginning of lines or within lines, simple and slightly enlarged red text-initials open some sections or verses.

The folded reuse of the bifolium as a binding wrapper retains the columns in full and much or all of the margins on each page. For this reason, perhaps the reuse required no trimming down of the bifolium.

The original fold-line is visible on the present spine of the binding, which employs 4 stitching stations, plus the endbands. The bifolium is moulded over the raised cords of the stitching.

The Psalter Texts

The Psalter Texts

In its present pasted state, with the text upright consistently with the orientation of the texts within the notebook, only one side of each folio is visible. These sides comprise the recto of the first folio (Folio ‘Ir’) on the front cover and the verso of the second (Folio ‘IIv’) on the back cover.

- The front cover (Folio Ir) carries the text of Psalm 77:57 (averterunt) – 66 (posteriora).

- The back cover (Folio IIv) carries the text of Psalm 87:2 ([coram/] te) – 11 (suscitabunt).

These portions demonstrate that, on this bifolium, in the original layout, the front folio preceded the back folio, and some leaves originally intervened between them. The presentation of text on the hidden sides of the bifolium (Folios ‘Iv’ and ‘IIr’) is partly discernible by the show-through onto its visible side(s). Image enhancement (as below) shows more of its text and bichrome elements in the form of enlarged red initials.

The coverage of text per page on the fragment corresponds approximately to some 9½ to 10 lines as set out in the online-printed edition reproduced below.

The Hidden Inside of the Bifolium (Folios Iv / IIr) Pasted to the Cardboard Cover

Presumably a similar amount of text occupies the inaccessible other sides of the leaves, extending the coverage on the fragment to the end of the long Psalm 77 and into Psalm 78 (say verse 3 or 4) on the verso of the first folio, and picking up within Psalm 85 (say verse 16 or 17), presenting all of the short Psalm 86, and beginning Psalm 87 (to the penultimate word coram of verse 2) on the recto of the second folio.

The Lost Innards of the Original Quire

Between Folios I/II of the Surviving Bifolium

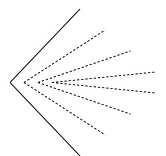

At approximately the same rate of script, the missing text between the two leaves of the bifolium could have filled some six leaves. If they uniformly comprised bifolia, rather than, say, a mixture of bifolia and single leaves, then perhaps three bifolia formerly stood between the first and last leaves of the surviving fragment.

The fragment could have been the outer bifolium of a quaternion of eight leaves comprising bifolia, as shown here, with solid lines to indicate the survivor and dotted lines for the lost leaves — although other numbers and arrangements are possible. For example, depending upon practice(s) at the center producing the manuscript, the former quire might have been longer, so that ‘our’ bifolium was not outermost, nesting all the others, but rather an inner guardian, itself nested by the outer one(s). Single leaves within the quire are possible, too. Who knows? Yet.

The fragment could have been the outer bifolium of a quaternion of eight leaves comprising bifolia, as shown here, with solid lines to indicate the survivor and dotted lines for the lost leaves — although other numbers and arrangements are possible. For example, depending upon practice(s) at the center producing the manuscript, the former quire might have been longer, so that ‘our’ bifolium was not outermost, nesting all the others, but rather an inner guardian, itself nested by the outer one(s). Single leaves within the quire are possible, too. Who knows? Yet.

In moving this bifolium into position as the parchment cover for the notebook, the binder would have easily retained the orientation of the bifolium with its original outer side (folios Ir/IIv) facing outward.

Upheavals and Discarding/Reusing Bits of Medieval Books in France in Modern Times

If an observer choose to glance at the contents of the ‘innards’ of the notebook for a cursory indication of the probable date at or from which the medieval bifolium found its reuse, and happened to focus only upon the seller’s contents list on the first (that is, presently the first) front page, with its stated date-range, the assumption might arise that the reuse of parts or all of the medieval religious manuscript could have fitted readily into the period of upheavals which marked the French Revolution. Not so, given the contents list on the inside front cover and the excised leaves.

The paper notebook presumably began life as a blank book prepared for generalized use and obtainable ‘off the shelf’. Open for Business.

It is useful to observe that not all dismemberments and reuses of medieval manuscripts in France require the upheaval of the French Revolution as an explanation or as a necessary date-range. In evidence, among many possible cases, we submit for consideration an example which we have reported already: A Part-Leaf from the ‘Life of Saint Blaise’. That case represents a partial leaf from a lectionary reused as cover for a paper register of records in French, with dated entries relating to the Plauzat region in the Auvergne for various years in the 18th century, for example for 1722 and 1730 (with some corrected or revised dates).

Books have their fates. And their dates, in case, of reuse.

The Former Manuscript

In the medieval period(s), the text of the Psalms customarily circulated as part of the Bible, on its own, or in the company of other texts pertaining to prayer and song. The double-column layout here implies that the original manuscript containing this Psalter text comprised a Psalter or a Breviary — rather than, say, a Book of Hours, characteristically laid out in single columns.

The Script and Coloring as Symptoms

An initial assessment of the original script, layout, and presentation observes that the manuscript may have a Southern French origin. The rotunda Gothic script seems Italianate, but it stands upright (vertical), without spiky features. The initials — at least on this bifolium, which has no Psalm beginnings which might call for a higher standard of focus and embellishment — are only in red (with no blue), nor with any flourishing. Presumably the manuscript was made in the late 13th or 14th century.

The Psalms as Standard

To illustrate the span of text on the leaves and the intervals or gaps in lost text between them, we offer a version based upon an online edition of the Vulgate version: Douay–Rheims Bible online, which adds the modern verse-numerations. The indicated span shows the length of the presumed textual gap between the surviving leaves of the bifolium. Here missing portions before and after the 2 parts of this bifolium are shown in BLUE. Editorial notes indicating the beginning and ending of surviving portions are shown in RED.

Psalm 77

[1] intellectus Asaph adtendite populus meus legem meam inclinate aurem vestram in verba oris mei [2] aperiam in parabola os meum eloquar propositiones ab initio [3] quanta audivimus et cognovimus ea et patres nostri narraverunt nobis [4] non sunt occultata a filiis eorum in generationem alteram narrantes laudes Domini et virtutes eius et mirabilia eius quae fecit [5] et suscitavit testimonium in Iacob et legem posuit in Israhel quanta mandavit patribus nostris nota facere ea filiis suis

. . .

[56] et temptaverunt et exacerbaverunt Deum excelsum et testimonia eius non custodierunt [57] et [/ FIRST RECTO = Folio Ir STARTS HERE] averterunt se et non servaverunt pactum quemadmodum patres eorum conversi sunt in arcum pravum [58] et in ira concitaverunt eum in collibus suis et in sculptilibus suis ad aemulationem eum provocaverunt [59] audivit Deus et sprevit et ad nihilum redegit valde Israhel [60] et reppulit tabernaculum Selo tabernaculum suum ubi habitavit in hominibus

[61] et tradidit in captivitatem virtutem eorum et pulchritudinem eorum in manus inimici [62] et conclusit in gladio populum suum et hereditatem suam sprevit [63] iuvenes eorum comedit ignis et virgines eorum non sunt lamentatae [64] sacerdotes eorum in gladio ceciderunt et viduae eorum non plorabuntur [65] et excitatus est tamquam dormiens Dominus tamquam potens crapulatus a vino

[66] et percussit inimicos suos in posteriora [FIRST RECTO = Folio Ir ENDS HERE / INACCESSIBLE FIRST VERSO = Folio Iv STARTS HERE; NOT SURE WHERE IT ENDS; SAY AROUND Psalm 78:2 or 3] obprobrium sempiternum dedit illis [67] et reppulit tabernaculum Ioseph et tribum Effrem non elegit [68] et elegit tribum Iuda montem Sion quem dilexit [69] et aedificavit sicut unicornium sanctificium suum in terra quam fundavit in saecula [70] et elegit David servum suum et sustulit eum de gregibus ovium de post fetantes accepit eum

[71] pascere Iacob servum suum et Israhel hereditatem suam [72] et pavit eos in innocentia cordis sui et in intellectibus manuum suarum deduxit eos

Psalm 78

[1] psalmus Asaph Deus venerunt gentes in hereditatem tuam polluerunt templum sanctum tuum posuerunt Hierusalem in pomorum custodiam [2] posuerunt morticina servorum tuorum escas volatilibus caeli carnes sanctorum tuorum bestiis terrae [3] effuderunt sanguinem ipsorum tamquam aquam in circuitu Hierusalem et non erat qui sepeliret

. . . [4–13]

Psalm 79 [1–20]

Psalm 80 [1–17]

Psalm 81 [1–8]

Psalm 82 [1–19]

Psalm 83 [1–13]

Psalm 84 [1–14]

Psalm 85 [1–17]

. . . [NOT SURE WHERE Folio IIr BEGINS; SAY AROUND Psalm 85:16 or 17]

[16] respice in me et miserere mei da imperium tuum puero tuo et salvum fac filium ancillae tuae [17] fac mecum signum in bono et videant qui oderunt me et confundantur quoniam tu Domine adiuvasti me et consolatus es me

Psalm 86

|

[1] filiis Core psalmus cantici fundamenta eius in montibus sanctis [2] diligit Dominus portas Sion super omnia tabernacula Iacob [3] gloriosa dicta sunt de te civitas Dei diapsalma [4] memor ero Raab et Babylonis scientibus me ecce alienigenae et Tyrus et populus Aethiopum hii fuerunt illic [5] numquid Sion dicet homo et homo natus est in ea et ipse fundavit eam Altissimus [6] Dominus narrabit in scriptura populorum et principum horum qui fuerunt in ea diapsalma [7] sicut laetantium omnium habitatio in te |

Psalm 87

|

[1] canticum psalmi filiis Core in finem pro Maeleth ad respondendum intellectus Eman Ezraitae [2] Domine Deus salutis meae die clamavi et nocte coram [/ INACCESSIBLE SECOND RECTO = Folio IIr ENDS HERE / SECOND VERSO = Folio IIv STARTS HERE] te [3] intret in conspectu tuo oratio mea inclina aurem tuam ad precem meam [4] quia repleta est malis anima mea et vita mea in inferno adpropinquavit [5] aestimatus sum cum descendentibus in lacum factus sum sicut homo sine adiutorio [6] inter mortuos liber sicut vulnerati dormientes in sepulchris quorum non es memor amplius et ipsi de manu tua repulsi sunt [7] posuerunt me in lacu inferiori in tenebrosis et in umbra mortis [8] super me confirmatus est furor tuus et omnes fluctus tuos induxisti super me diapsalma [9] longe fecisti notos meos a me posuerunt me abominationem sibi traditus sum et non egrediebar [10] oculi mei languerunt prae inopia clamavi ad te Domine tota die expandi ad te manus meas [11] numquid mortuis facies mirabilia aut medici suscitabunt [SECOND VERSO = Folio IIv ENDS HERE /] et confitebuntur tibi diapsalma [12] numquid narrabit aliquis in sepulchro misericordiam tuam et veritatem tuam in perditione [13] numquid cognoscentur in tenebris mirabilia tua et iustitia tua in terra oblivionis [14] et ego ad te Domine clamavi et mane oratio mea praeveniet te [15] ut quid Domine repellis orationem meam avertis faciem tuam a me [16] pauper sum ego et in laboribus a iuventute mea exaltatus autem humiliatus sum et conturbatus [17] in me transierunt irae tuae et terrores tui conturbaverunt me [18] circuierunt me sicut aqua tota die circumdederunt me simul [19] elongasti a me amicum et proximum et notos meos a miseria . . . Over and OutEnough for now to display this case of a reused medieval bifolium. Reclaimed as a bookish material perhaps of interest, it found a way to current recognition by virtue of the skin of its teeth and serendipity through personal connections. The owner sought my expertise; I responded. The case joined a collective of scholarly activity, which allowed for recognition of some of its characteristics. And so it moves forward among other spheres, perhaps to find better knowledge. Worth saying: I learned much from the chance to study the object over time, with safekeeping in my house, during different seasons and under varied forms of natural lighting, day or night. And under different spheres of consideration, preoccupation, and concern. Perhaps some new observers might wish to learn from the observations which I have not found the occasion to record in published form, as on this website. Been busy. Running a nonprofit educational corporation, among other tasks. Some of those efforts are recorded elsewhere on this website. If you are interested in those observations, please let me know. It could be easy to Contact Us. Across the ages, when the activities, aspirations, and frustrations of generations have little chance for recognition and resuscitation in later centuries or generations, let us pause a moment to reflect on the power of serendipity and a ready network, prepared who-knows-how and now-and-then, and how! ***** We thank the owner of the ensemble for permission to photograph, research, and publish its evidence. We thank colleagues, including Alison Beach and Adelaide Bennett, for their assessments of the probable date of the script. It was Adelaide who emphatically observed the layout as diagnostic for a Psalter rather than a Book of Hours. A detailed study of the surviving portions of the Notebook might determine more precisely the date at or after which the medieval bifolium was converted into its cover. Suffice, perhaps, for now is to show the materials in evidence for further consideration. ***** We continue to consider manuscript and related evidence. Please join us and offer your comments, suggestions, and improvements. ***** Next Stop: More Material Evidence, of course. ***** |