2022 RGME Spring and Autumn Symposia

on “Structured Knowledge”

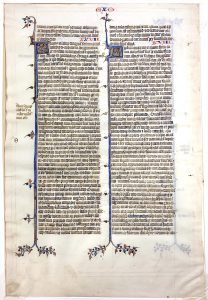

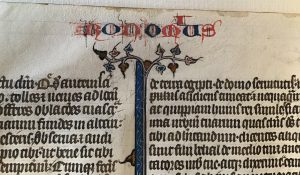

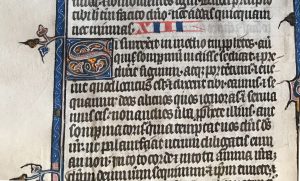

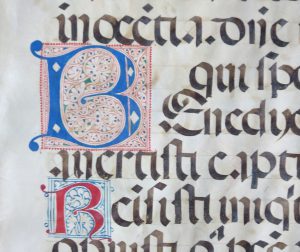

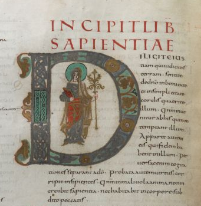

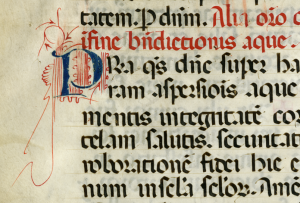

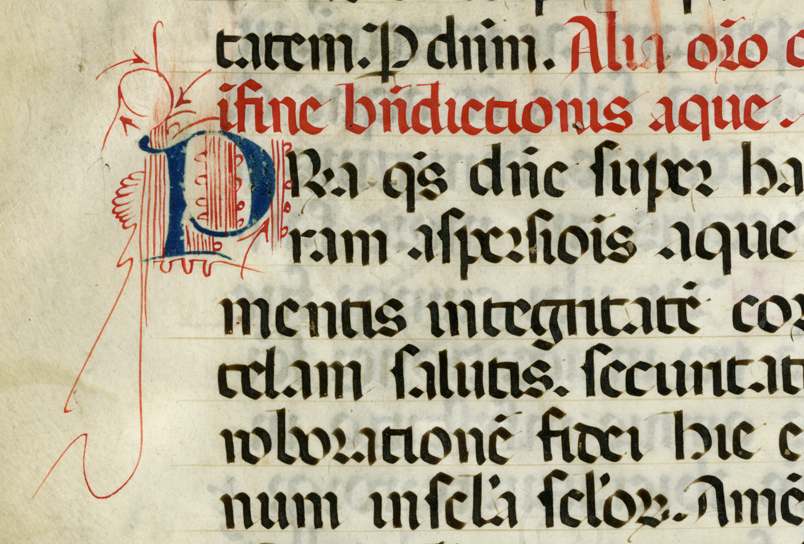

© British Library Board, London, British Library, Add. MS 1546, folio 262v, detail. Opening of the Book of Sapientia (“Wisdom”).

2 of 2: 2022 Autumn Symposium

“Supports for Knowledge”

Saturday, 15 October 2022

Symposium Program

9:00 am – 5:30 pm EDT

Online via Zoom

Sessions with Presentations and Discussion (“Q&A”)

Breaks for Coffee, Lunch, and Tea

Closing Keynote Presentation and Concluding Remarks

For Registration see below

[Posted on 5 October, with updates]

On the pair of Symposia, see 2022 Spring and Autumn Symposia

On Part 1 of this pair, see 2022 Spring Symposium on “Structures of Knowledge”

On Part 2, see 2022 Autumn Symposium on “Supports for Knowledge”

Here we present the Program for Part 2 on “Supports for Knowledge”, held on Saturday 15 October 2022 by Zoom

— Registration is required, with a limited number of places (see below).

The Program Booklet (in preparation) will present the Program and Abstracts of the Presentations and Responses, with multiple Illustrations. In accordance with our tradition of Program Booklets for our Symposia and some other events (see our Publications, it will be issued in printed form as well as digital form, with a downloadable pdf.

Timetable

Session 1. 9:00–10:30 am EDT

Brief Introduction to the Symposium and Welcome

“Teaching with (and through) Manuscripts, Part II”

Q&A

Break. 10:30–10:45 am

Session 2. 10:45 am – 12:15 pm

“Catalogs, Metadata, and Databases, Continued (Part III)”

Q&A

Lunch Break. 12:15–1:15 pm

–– During the Break. 12:30–12:50 pm

Presentation (at the time when the Speaker could attend)

David W. Sorenson (Allen Berman, Numismatist)

“A Jain Manuscript of the Seventeenth Century on Imported Watermarked Paper: An Early, Dated, Witness to Imported Paper Stocks in Indian Manuscripts”

As a contribution to our series on the “History and Uses of Paper”

Session 3. 1:15–2:45 pm

“The Living Library (Part II)”

Q&A

Break. 2:45–3:00 pm

Session 4. 3:00–4:30 pm

“Hybrid Books (Part I)”

Q&A

Break. 4:30–4:45 pm

Session 5. 4:45–5:30 pm EDT

“Books and Their Structures”

Closing Keynote Presentation and Concluding Remarks

*****

Sessions

Session 1. “Teaching with (and through) Manuscripts, Part II”

— continuing the series begun at the Spring Symposium on “Structures of Knowledge”

Presider

David Porreca (Department of Classical Studies, University of Waterloo)

Speakers

Caley McCarthy (Research Associate and Project Manager, Environments of Change, University of Waterloo)

and

Andrew Moore (Research Fellow, Environments of Change, and Associate Director, DRAGEN Lab, University of Waterloo)

“Collaborative Pedagogy with Medieval Manuscripts in a Digital Lab”

William H. Campbell (Director, Center for the Digital Text, University of Pittsburgh-Greensburg)

Amber McAlister (Assistant Professor, History & Architecture, University of Pittsburgh-Greensburg)

and

Connor Chinoy (Student at the University of Pittsburgh-Greensburg and member of the “History of the Book” class)

“Books in the Flesh: An Interdisciplinary Undergraduate Class with Medieval Manuscripts”

Q&A

*****

Mid-Morning Break

*****

Session 2. “Catalogs, Metadata, and Databases, Continued (Part III)”

— continuing our series

This is Part III in our series on these subjects, building upon Parts I and II, and leading to further Parts in 2023

See the Links of Interest (Catalogs , Metadata, and Databases: A Handlist of Links)

— for which suggestions and additions are welcome.

Presider

Jessica L. Savage (Art History Specialist, Index of Medieval Art)

Speakers

Jessica L. Savage

“Cataloguing Manuscript Iconography between Digital Covers at the Index of Medieval Art”

Barbara Williams Ellertson (The BASIRA Project and Research Group on Manuscript Evidence)

“A Painter, a Printer, and a Search for Shared Exemplars”

Katharine C. Chandler (Special Collections and Serials Cataloger, University of Arkansas Libraries)

“Manuscripts from Print: The Schwenkfelders and their Dangerous Books”

Respondent

David Porreca (Department of Classics, University of Waterloo)

“My $0.02 Worth”

Moderator for the Questions-and-Answers

Derek Shank (Research Group on Manuscript Evidence)

Q&A

*****

Lunch Break

Perhaps — TBD — during part of the Break

Presentation (from about 12:15–12:35 pm), if the Speaker might attend, depending on short-notice work timetables:

David W. Sorenson (Allan Berman, Numismatist)

“A Jain MS of the Seventeenth Century on Imported Watermarked Paper: An Early, Dated, Witness to Imported Paper Stocks in Indian Manuscripts”

*****

Session 3. “The Living Library (Part II)”

— continuing the series begun at the Spring Symposium on “Structures of Knowledge”

Presider

Jaclyn Reed (Department of English and Writing Studies, University of Western Ontario)

Speakers

Christine E. Bachman (Department of Art & Art History, University of Colorado at Boulder)

“Unbound, Dispersed, Resewn: The Flexible Codex in Eighth-Century Northwestern Europe”

Zoey Kambour (Post Graduate Fellow in European & American Art at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at the University of Oregon)

“Textual Interaction Through Artistic Expression: The Marginal Drawings in the Decretales Libri V of Pope Gregory IX (University of Oregon MS 027)”

David Porreca (Department of Classical Studies, University of Waterloo)

“The Warburg Institute Library: Where Idiosyncracy Meets User-Friendliness”

Respondent

Thomas E Hill (Art Librarian, Vassar College)

“Some Early Background to Warburg’s Project in Post-Wunderkammer Systematic Catalogues of the European Baroque and Enlightenment Periods”

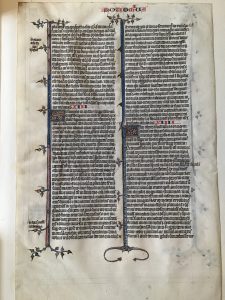

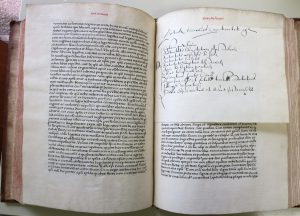

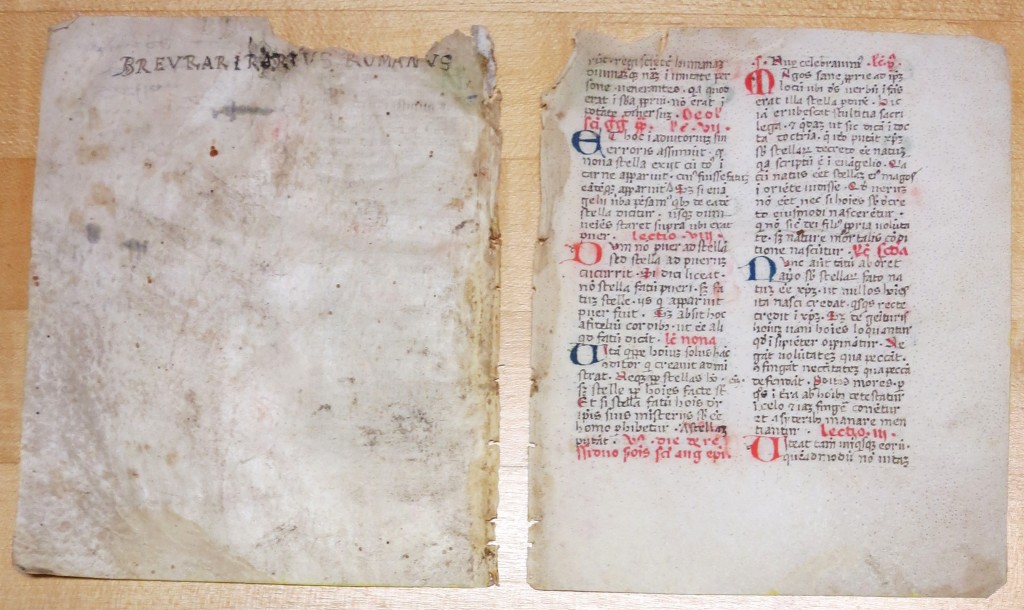

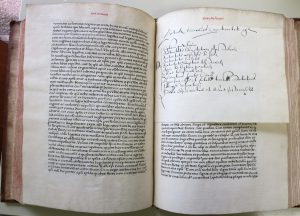

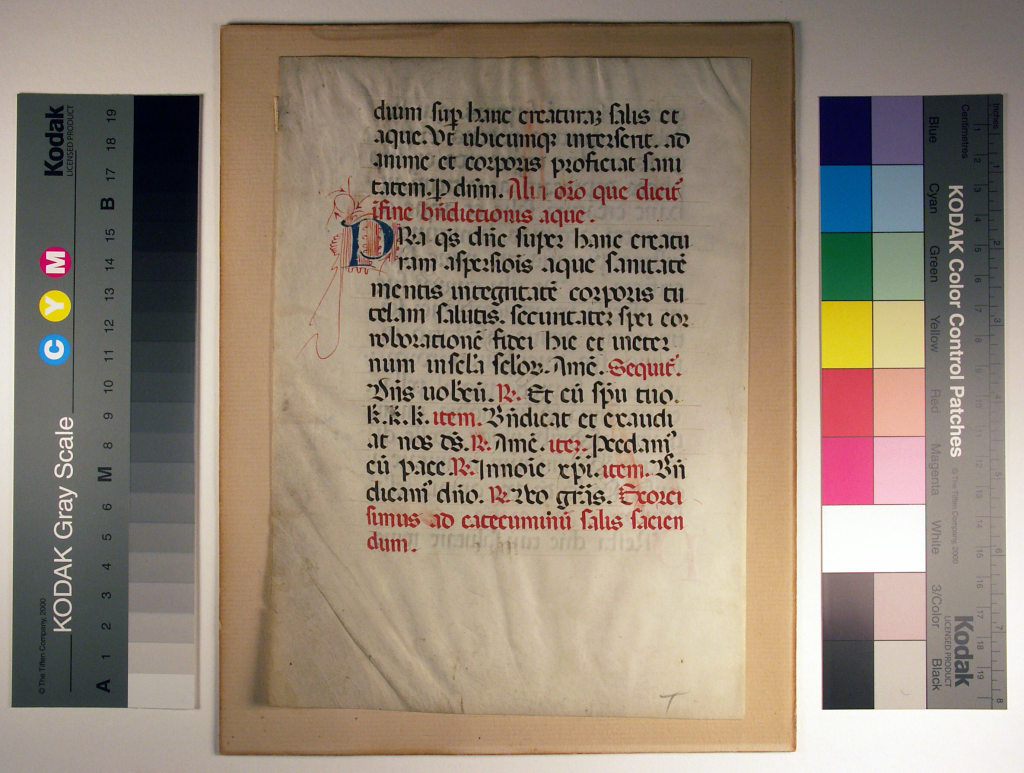

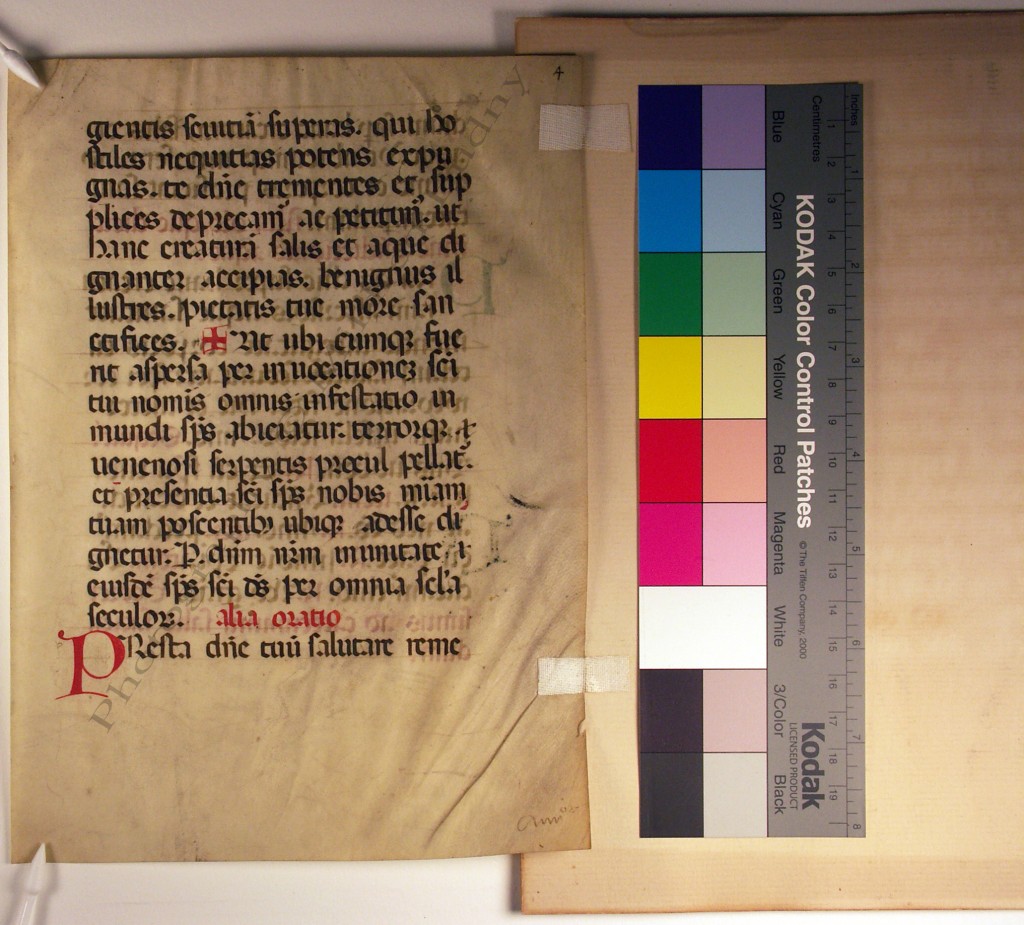

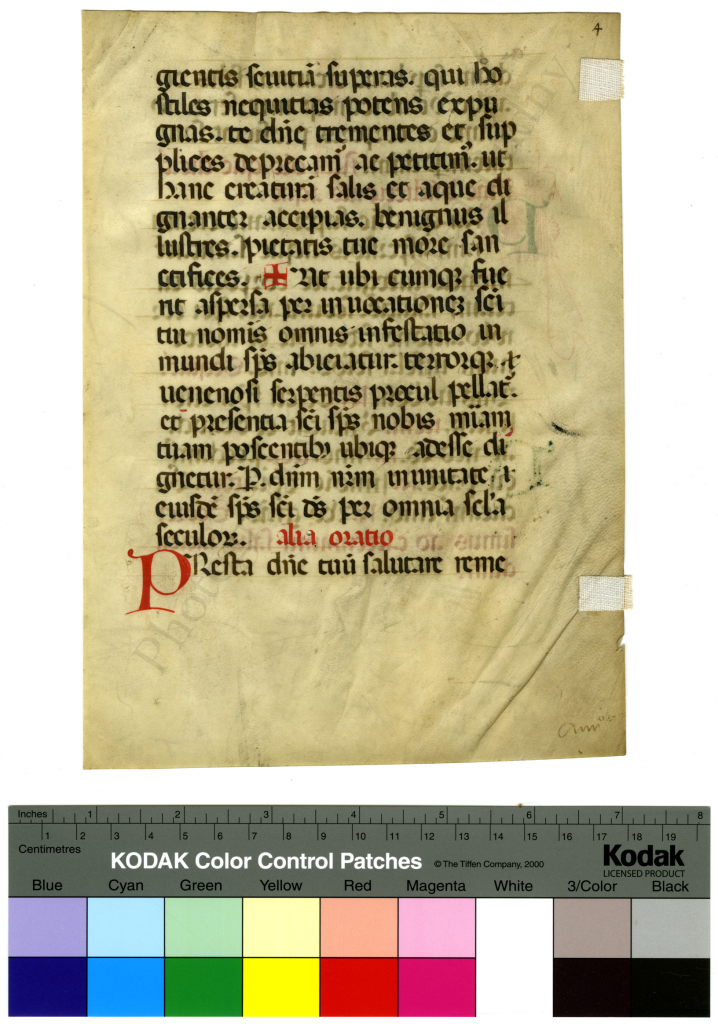

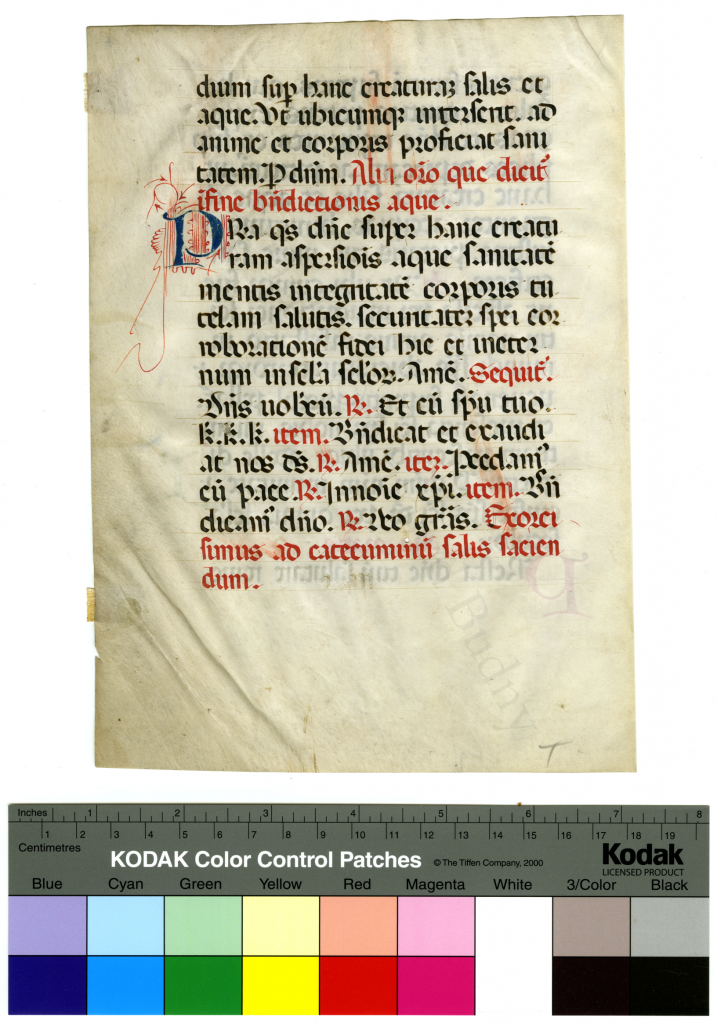

Private Collection, Le Parc Abbey, Theological Volume, Part B and added Part-Leaf (or Bookmark) between folios 103–104. Photography Mildred Budny.

Q&A

*****

Mid-Afternoon Break

*****

Session 4. “Hybrid Books (Part I)”

— beginning a series for which more sessions are planned

Presider

Justin Hastings (University of Delaware)

Speakers

Hannah Goeselt (Library and Information Science (MS): Cultural Heritage Informatics, Simmons University, Boston)

“Structures of Art and Scripture in Otto Ege’s ‘Cambridge Bible’ (Ege Manuscript 6)”

Jennifer Larson (Department of Classics, Kent State University)

“Printed and Scribed: A Collector’s View of Hybrid Books”

Linde M. Brocato (Cataloging & Metadata Librarian, University of Miami Libraries)

“Paths of Access and Horizons of Expectation, II: From Book-In-Hand to Catalog(ues)”

N. Kıvılcım Yavuz (Lecturer in Medieval Studies and Digital Humanities, School of History, University of Leeds)

“Bound With: Towards a Typology of Hybrid Codices”

Q&A

*****

Tea Break

*****

Session 5. “Books and Their Structures”

Presider

Mildred Budny (Director, Research Group on Manuscript Evidence)

Closing Keynote Presentation

Linde M. Brocato (Cataloging & Metadata Librarian, University of Miami Libraries)

“Hybrid Books: Fragments and Compilatio, Structure and Heuristic in Richard Twiss’s Farrago”

Discussion & Brief Concluding Remarks

Mildred Budny

“Structured Knowledge, Structures of Knowledge, and Supports for Knowledge: A Framework for the Year”

*****

Closing Keynote Presentation

“Hybrid Books:

Fragments and Compilatio, Structure and Heuristic in

Richard Twiss’ Farrago“

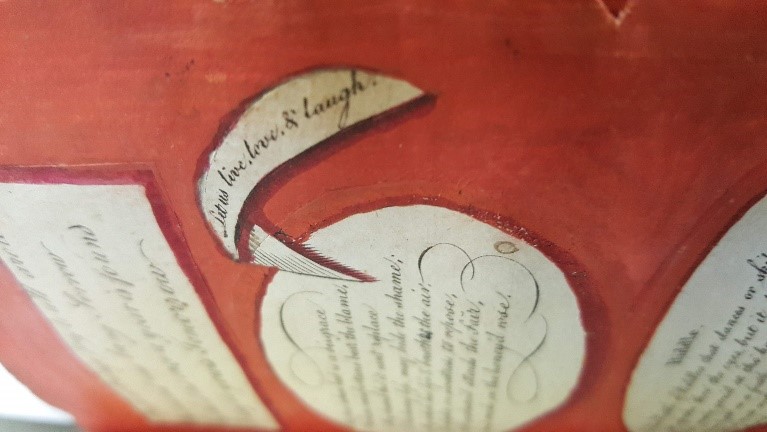

In the group of artists’ books from the Ruth and Marvin Shackner Archive of Concrete Poetry purchased by the University of Miami Special Collections, there is an extraordinary volume, sold by a vendor as late 19th century, anonymous, and an artist’s book avant la lettre. Careful analysis for bibliographical cataloging revealed the error in all these assertions.

In this presentation, I will lay out both the process of that analysis, and its results, along with reflections on hybrid books of various kinds. My reflections will encompass the kinds of structured information that make their way into databases, and structuring codes of cataloging and bibliography, all of which are necessary but not sufficient for our understanding and convivencia with books

kaufen cialis

, which are always already hybrid. In these reflections, I will bring together many of the strands of thinking we have all worked to weave together in the symposium.

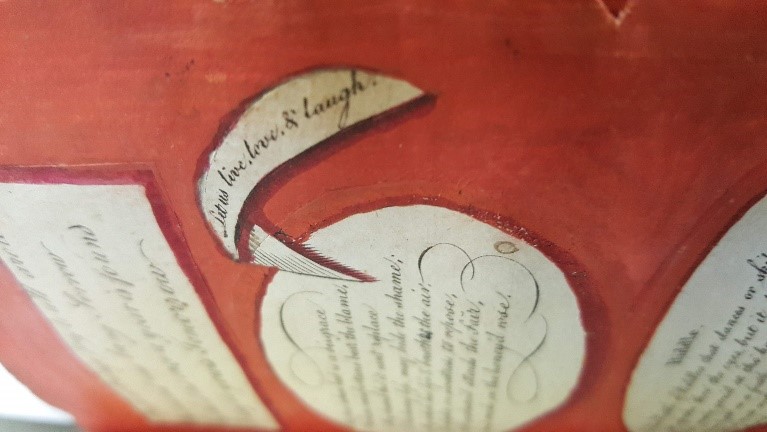

Richard Twiss, Farrago, held in the Unversity of Miami Special Collections, Artists’ Books Collection. Sidelong View. Photograph Linde M. Brocato.

Glimpses of the volume comprising Farrago compiled by the writer, traveler, chess-player, and would-be paper manufacturer Richard Twiss (1749–1821) can be seen in our blogpost called “I Was Here”, with photographs by Linde M. Brocato.

Concluding Remarks

Mildred Budny

“Structured Knowledge, Structures of Knowledge, and Supports for Knowledge: A Framework for the Year”

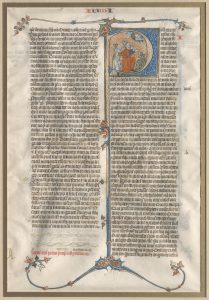

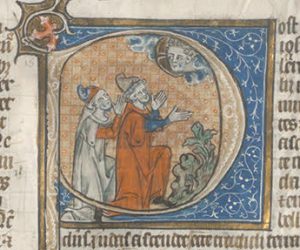

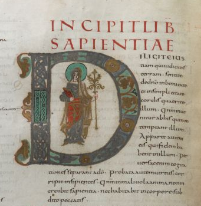

© British Library Board, London, British Library, Cotton MS Cleopatra C. viii, folio 36r, top: Sapientia in her Temple. Prudentius, Psychomachia, in a Canterbury copy of the late tenth or early eleventh century.

*****

To register for the Symposium, visit 2022 Autumn Symposium Registration. Places are limited.

Questions? Contact [email protected].

*****

Suggestion Box

Do you have suggestions for subjects for our events, or offers to participate? Please let us know.

If you wish to join our events, please contact [email protected].

For updates, watch this space, and visit:

Please leave your Comments below, Contact Us, and visit our FaceBook Page and Twitter Feed (@rgme_mss). We look forward to hearing from you

We invite you to donate to our nonprofit educational mission. Donations may be tax-deductible. We welcome donations in funds and in kind:

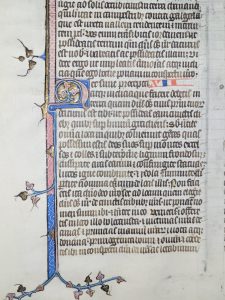

Floral Motif as Lower Border in a Book of Hours. Photography Mildred Budny.

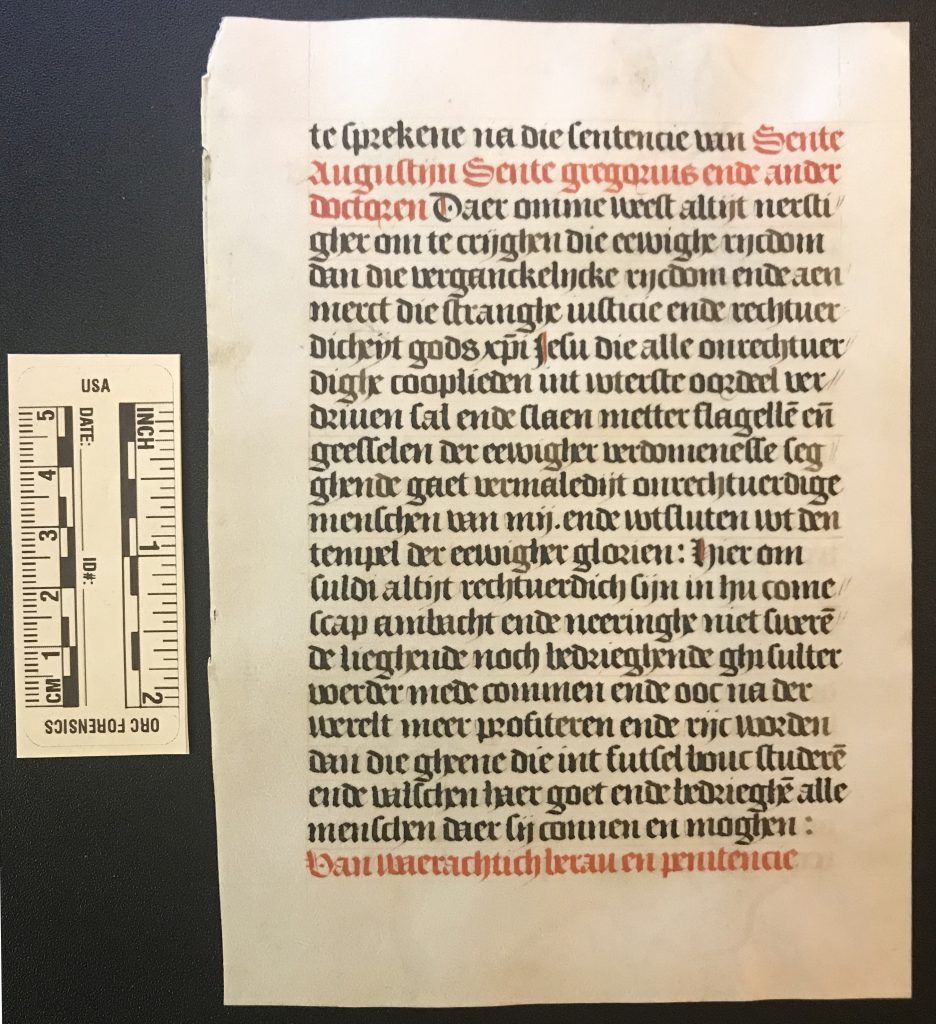

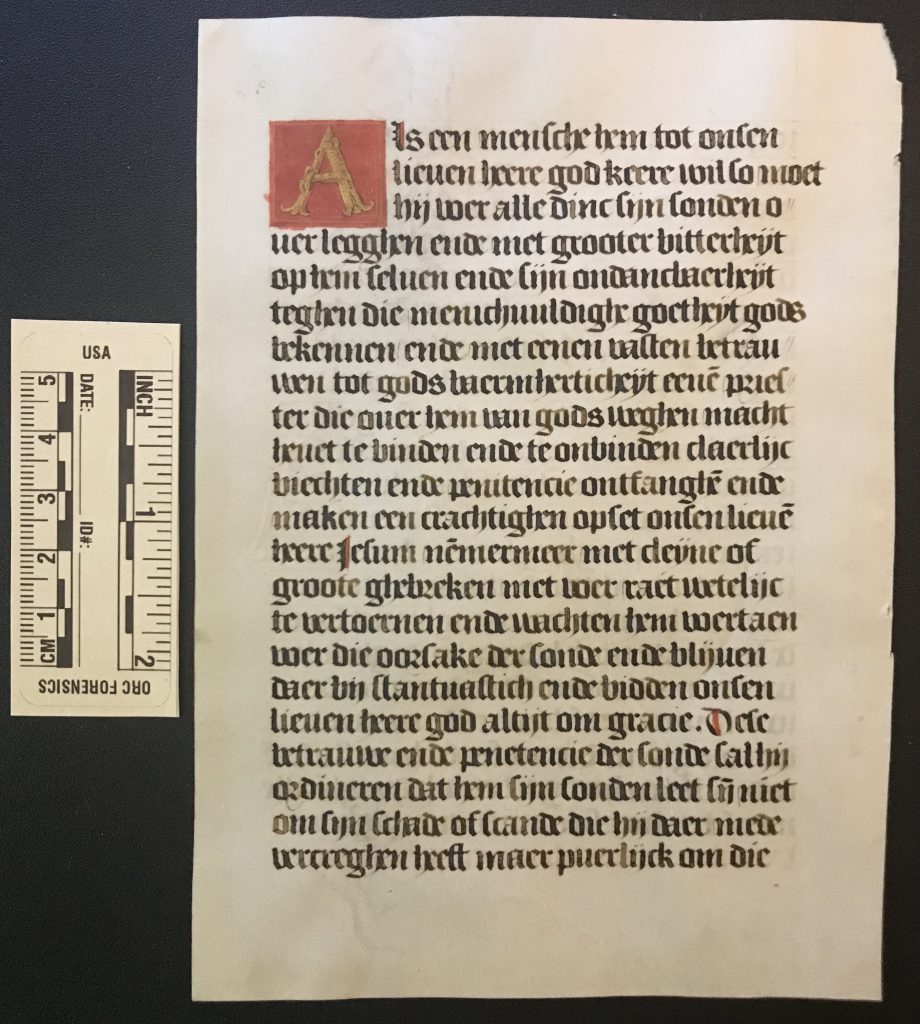

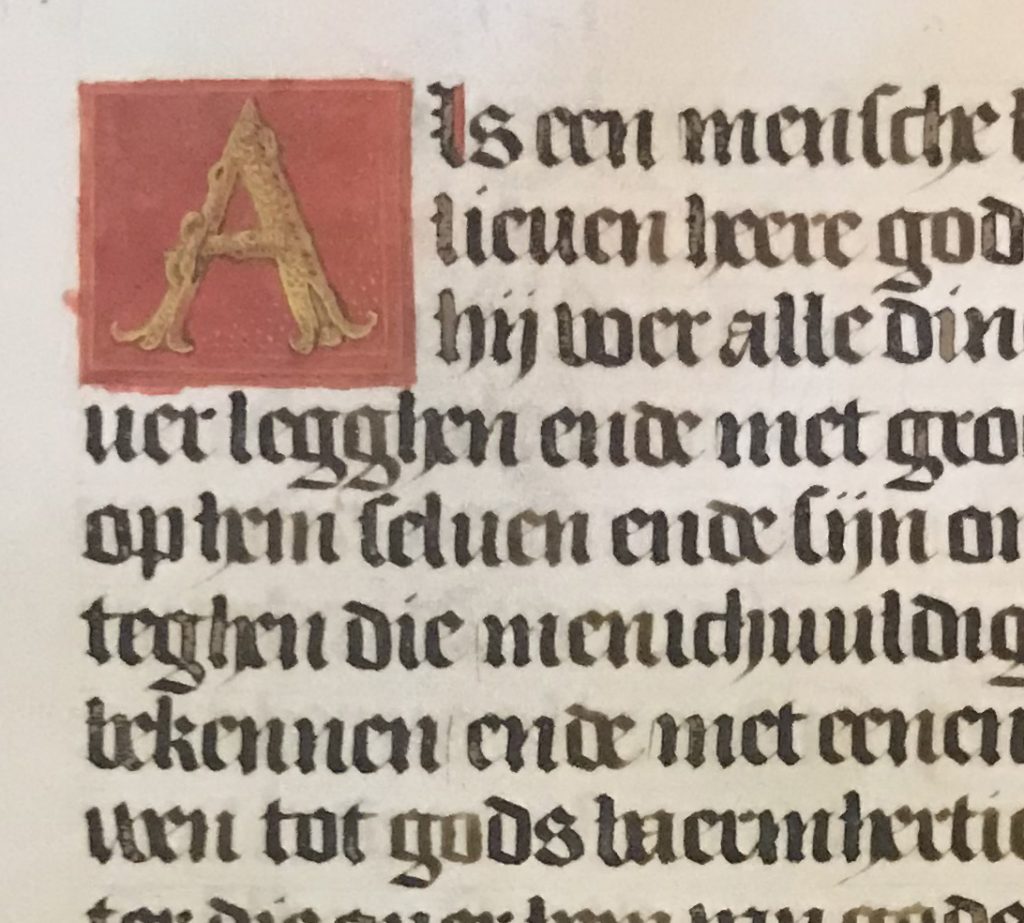

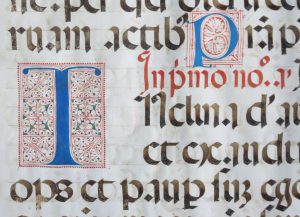

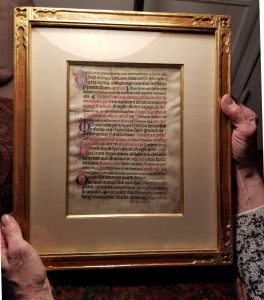

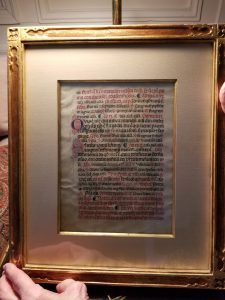

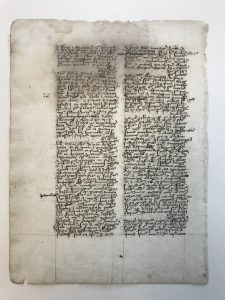

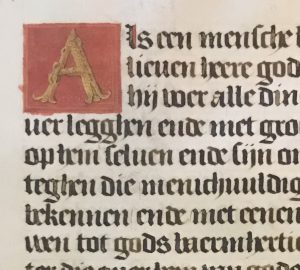

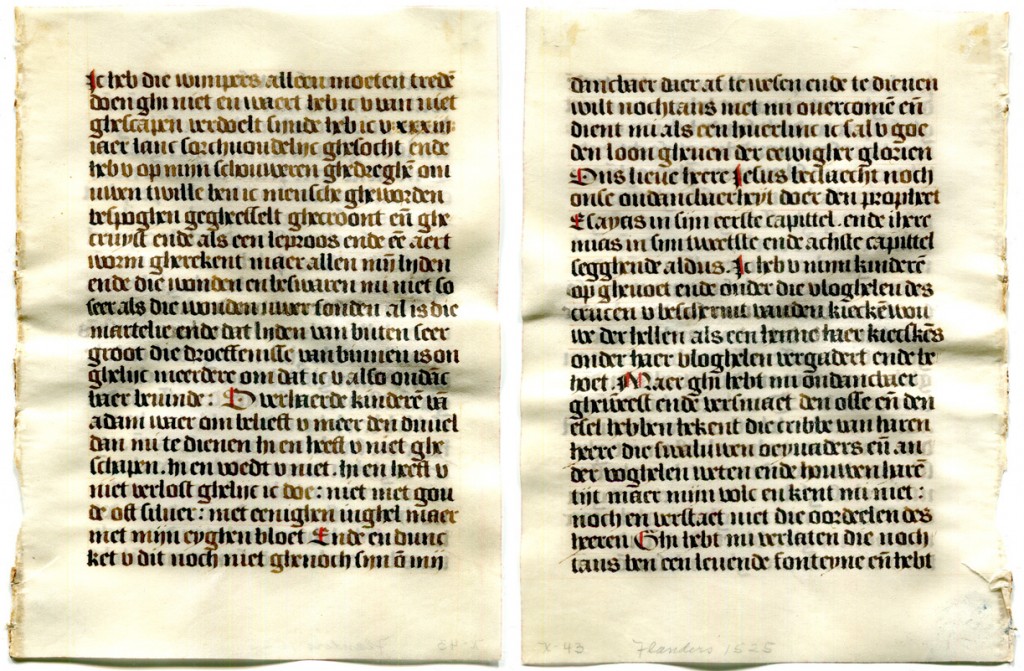

, owned and dismembered by Otto F. Ege” width=”1024″ height=”671″ /> Private Collection. Detached Leaf from ‘Otto Ege Manuscript 214’ (Dutch Prayerbook), Both Sides of the Leaf

, owned and dismembered by Otto F. Ege” width=”1024″ height=”671″ /> Private Collection. Detached Leaf from ‘Otto Ege Manuscript 214’ (Dutch Prayerbook), Both Sides of the Leaf