Otto Ege’s Aquinas Manuscript in Humanist Script

(‘Ege Manuscript 40’)

— Part I of III in a series on this manuscript —

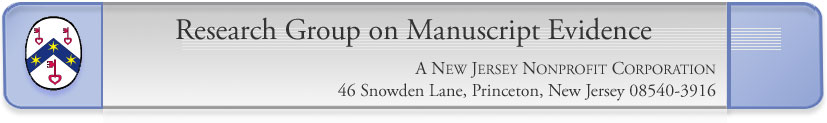

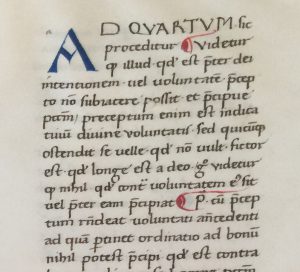

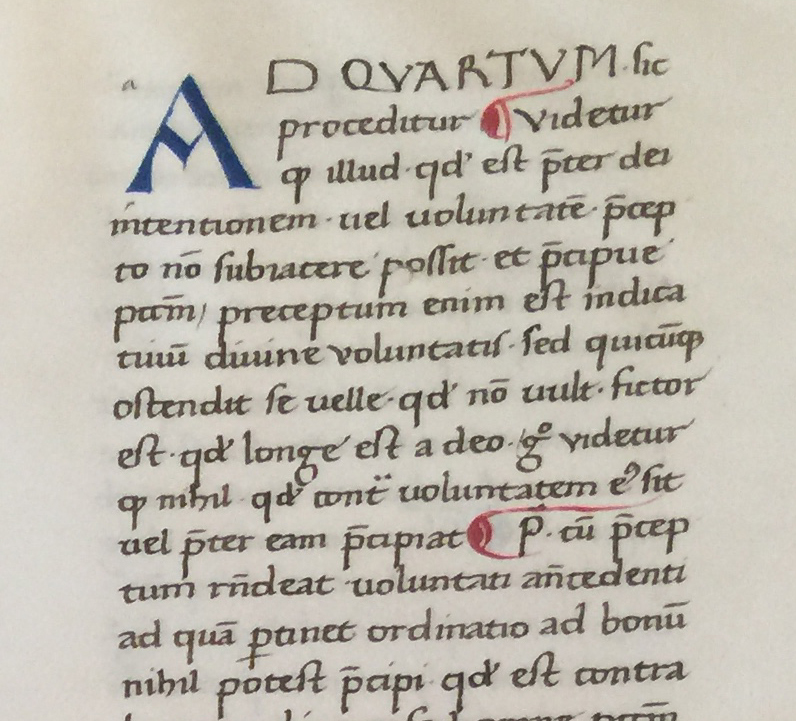

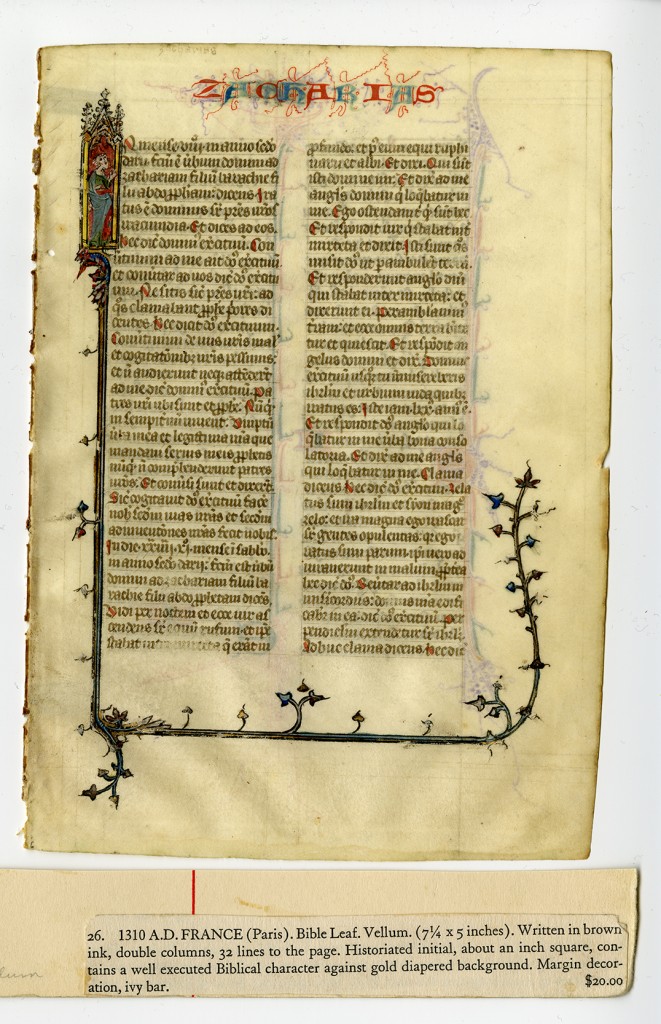

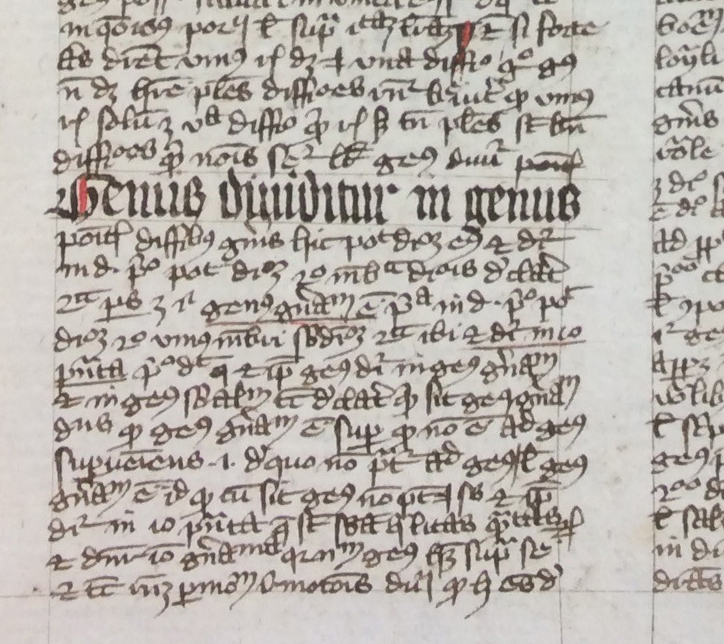

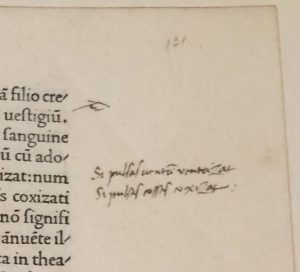

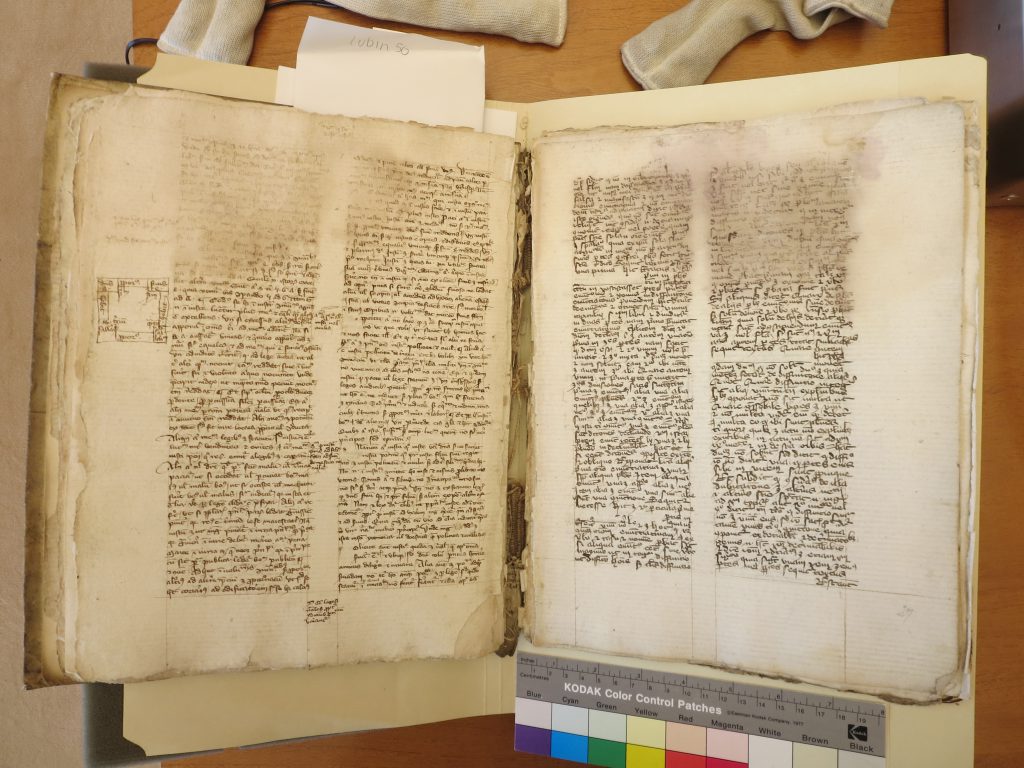

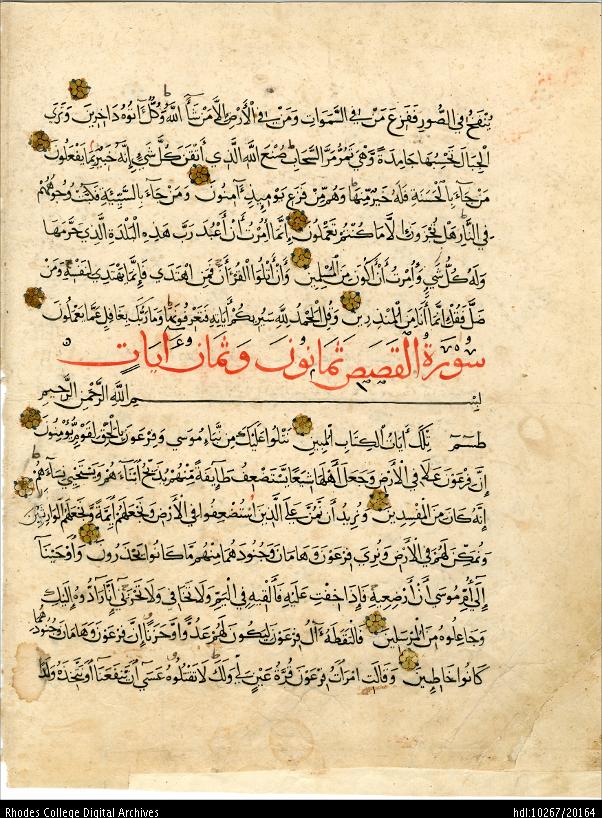

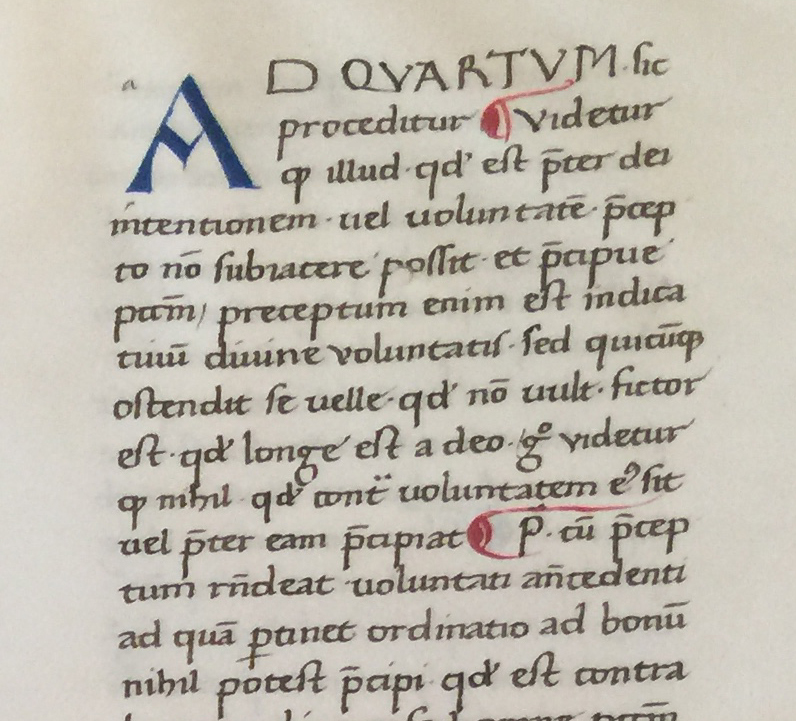

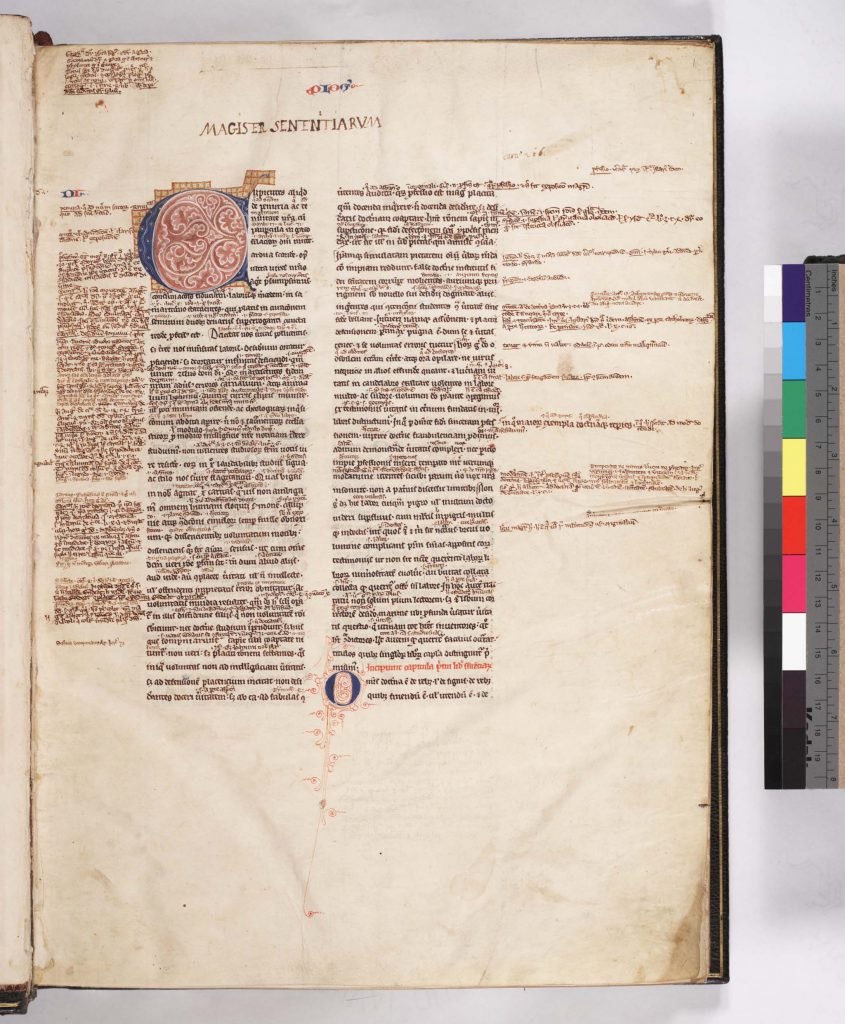

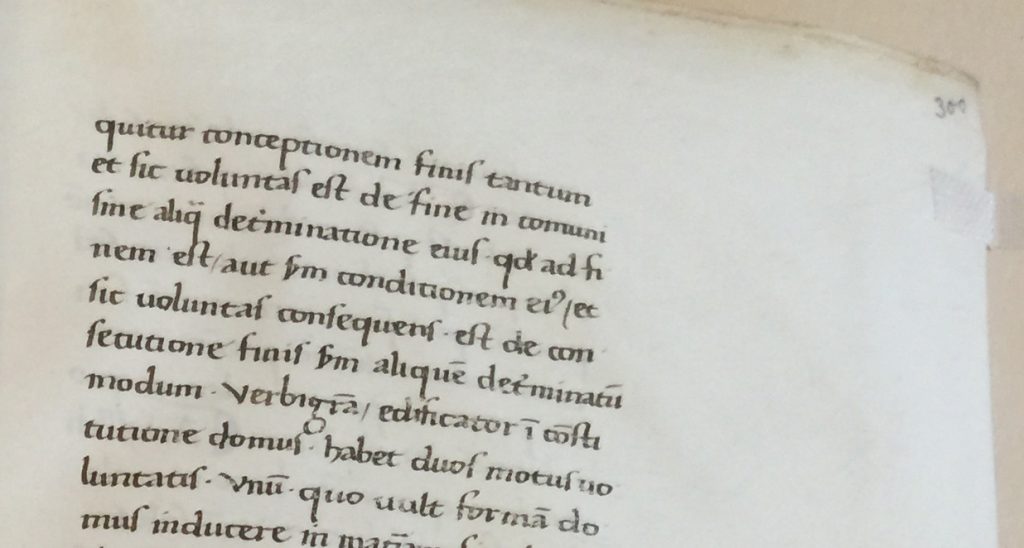

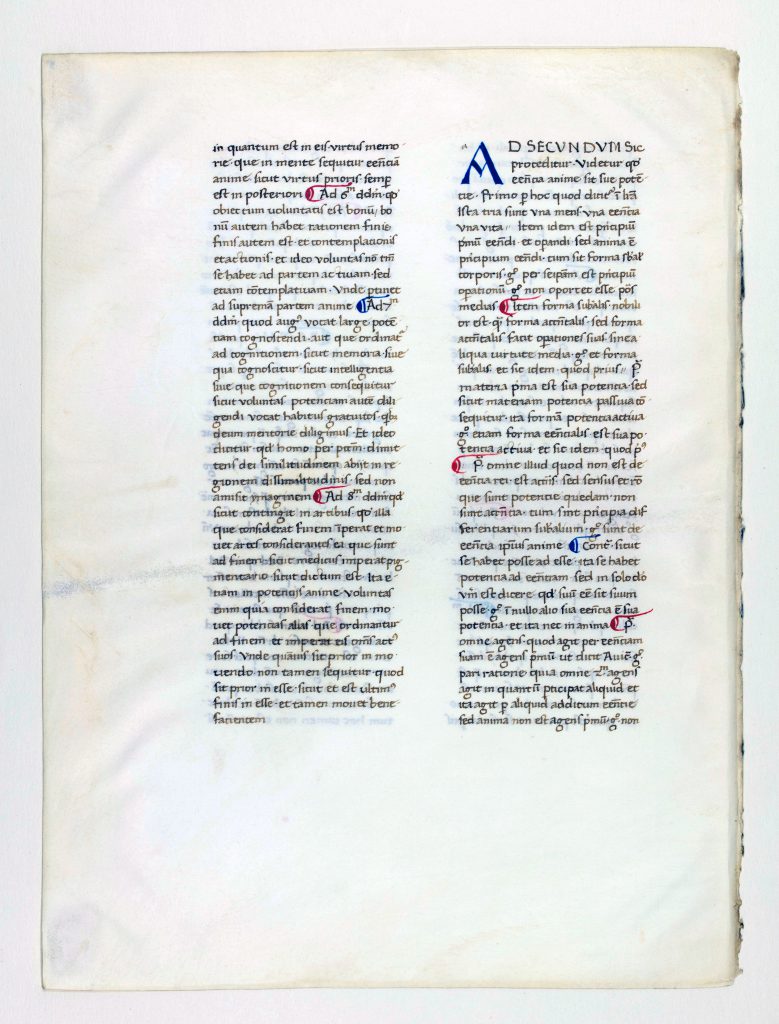

Private Collection, Ege’s FBNC Portfolio, Aquinas Leaf, Recto, Detail. Reproduced by Permission.

Thomas Aquinas, Commentary on Book I of Peter Lombard’s Sentences

Written in Latin on vellum

Italy, probably late 15th Century (circa 1475)

Circa 288 × 210 mm <Written area circa 178 × 130 mm>

Double columns of 37 lines

in Humanist Script (with Gothic Features)

*****

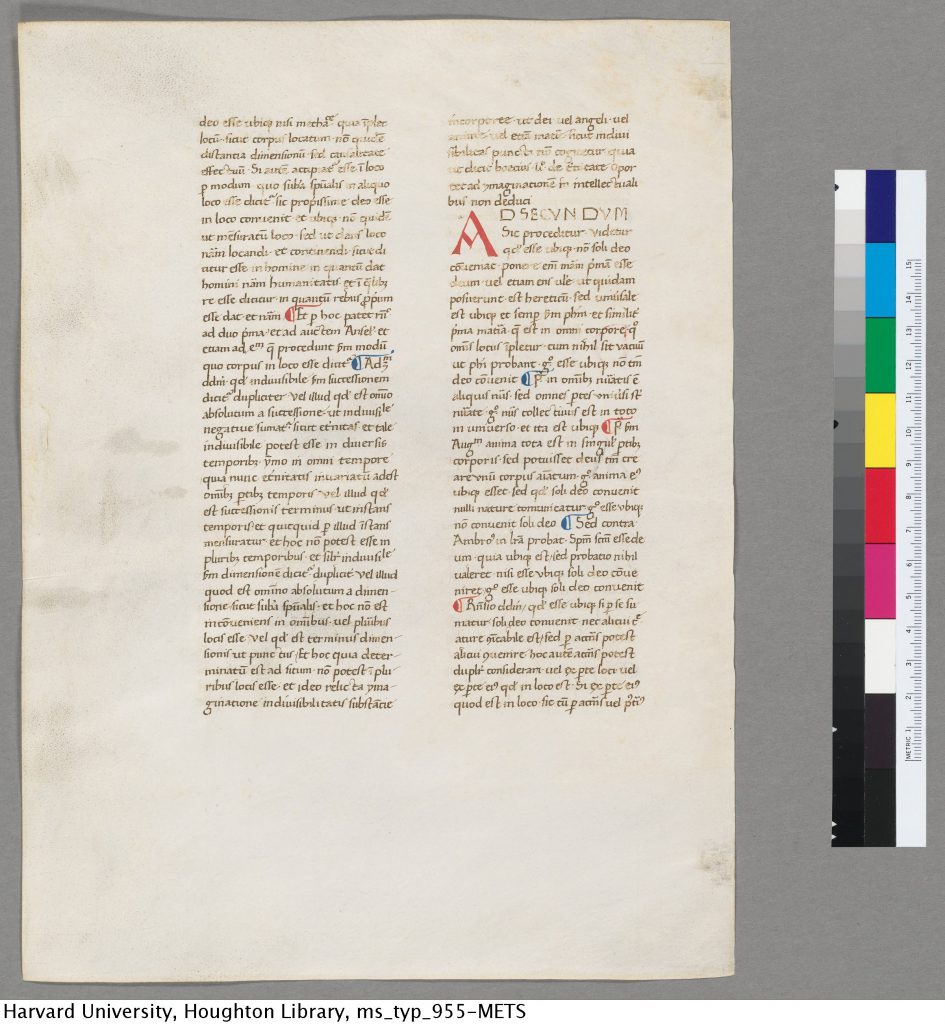

Folio 300

Super Sententiis, Liber 1, Distinctio 47, Quaestio 1,

Articulo 3 (ad 1 [3340]) – Articulo 4 (sed contra 1 [3349])

With Initials and Pilcrows (Paragraph-marks) in Red or Blue

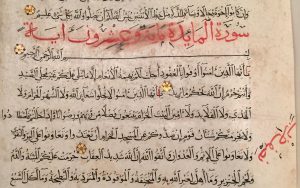

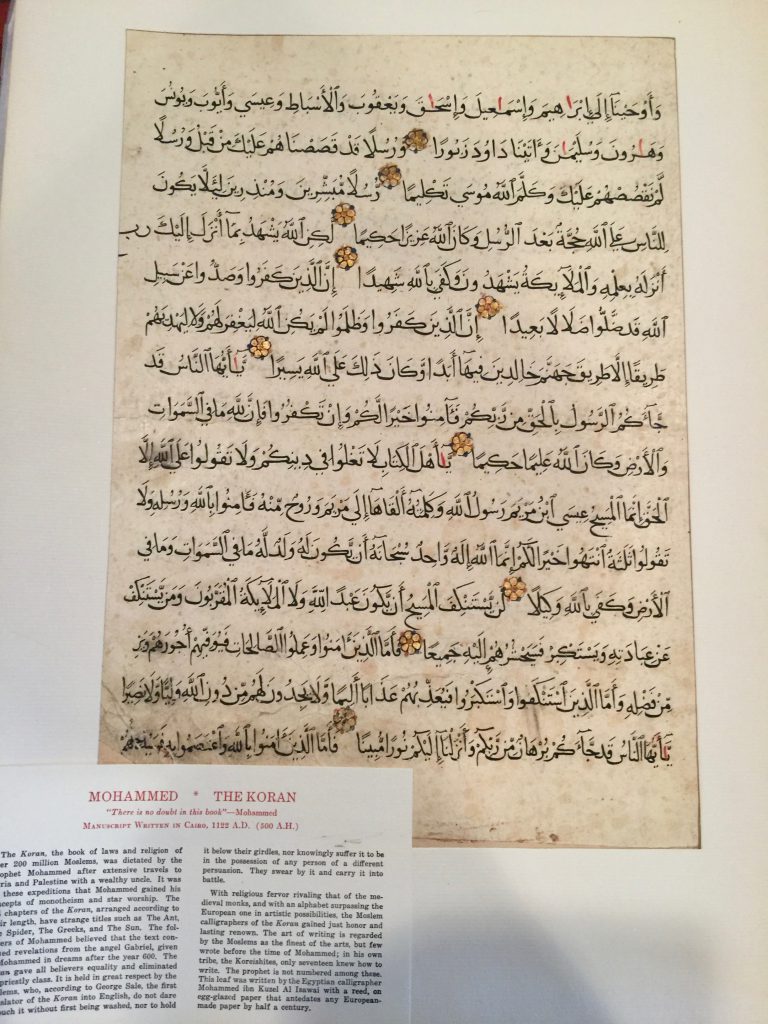

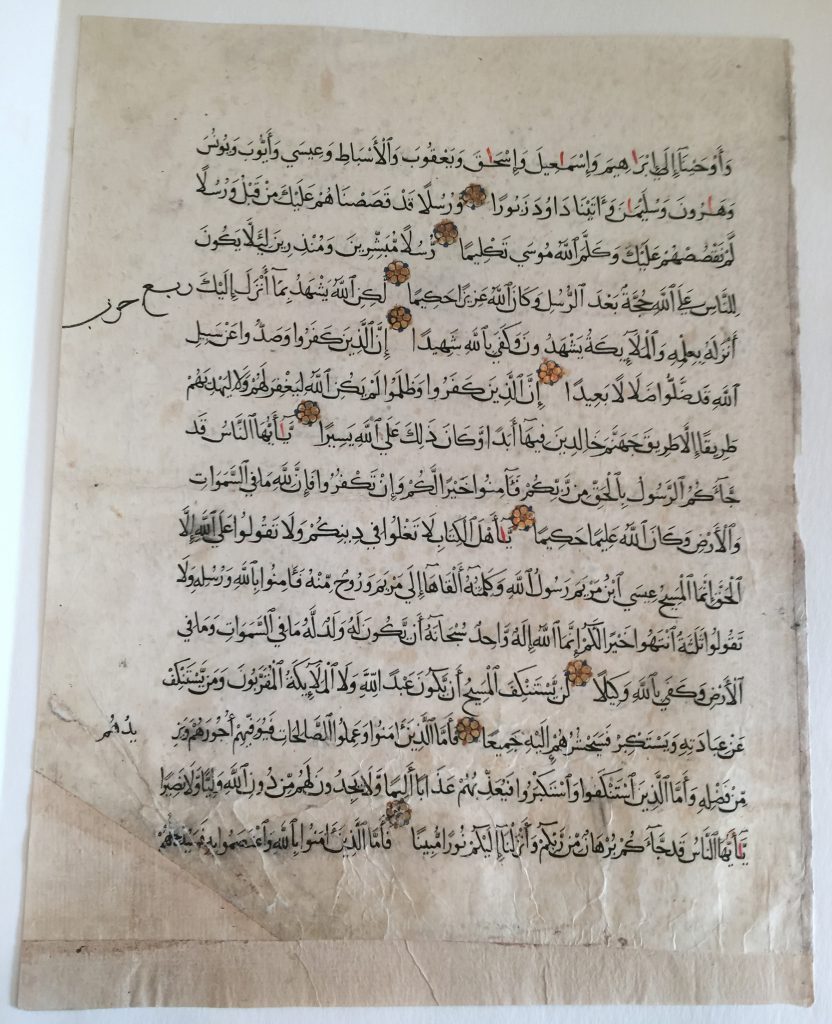

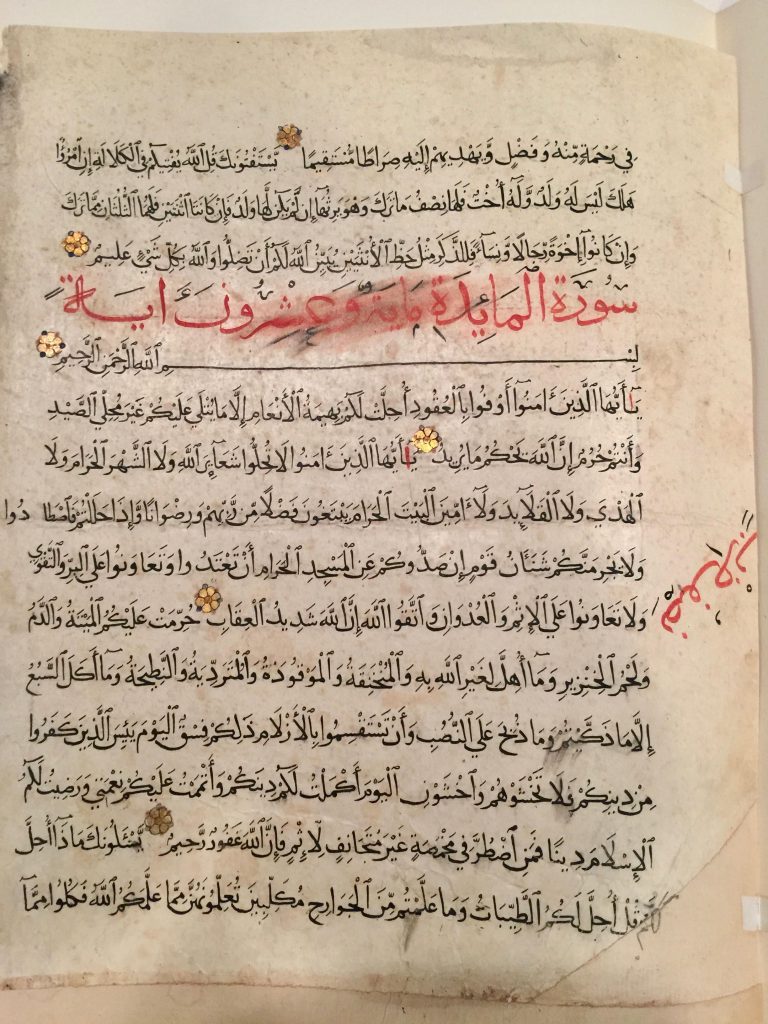

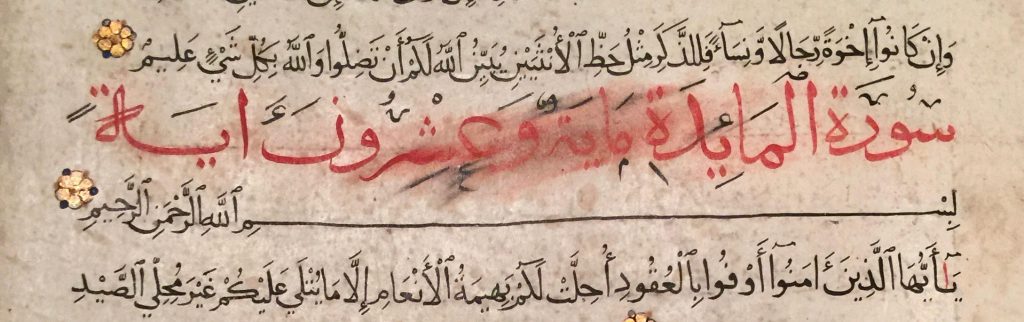

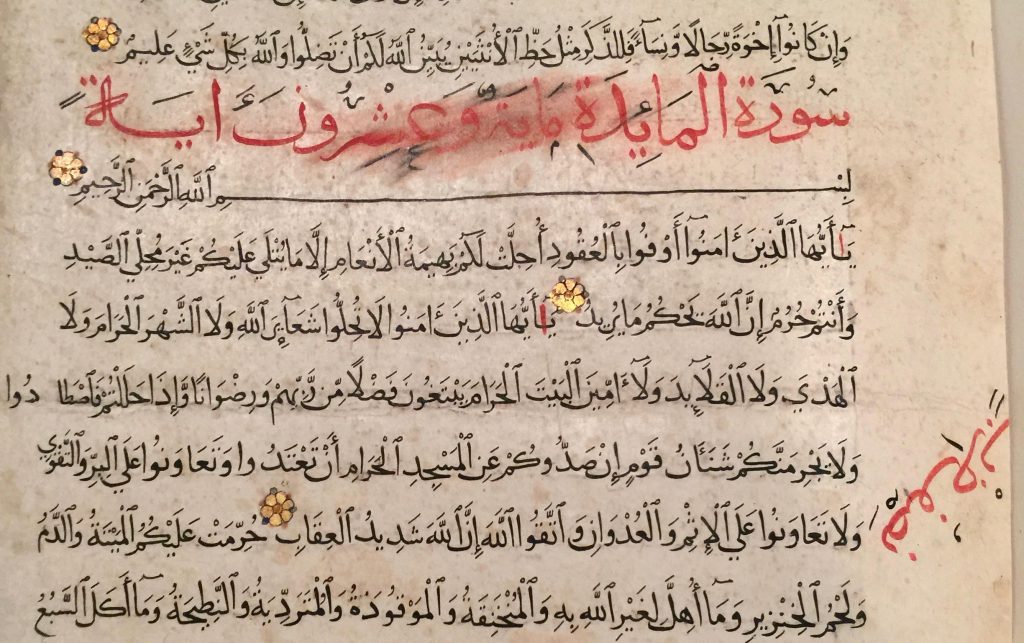

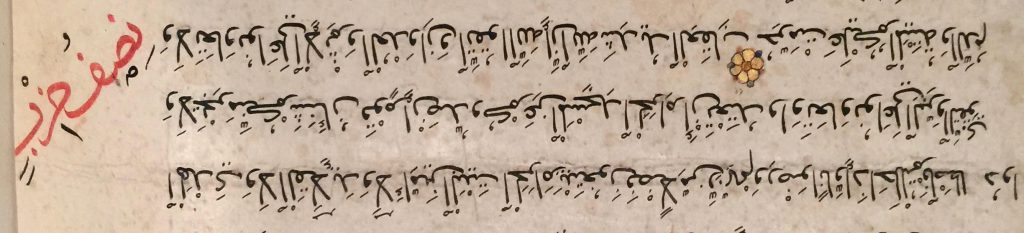

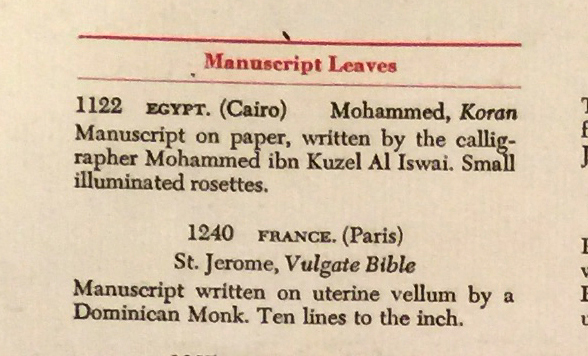

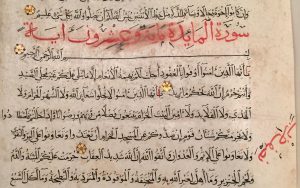

Private Collection, Koran Leaf in Ege’s Famous Books in Nine Centuries (Ege MS 53), Back of Leaf, Detail. Reproduced by permission.

We continue to explore a newly revealed Set of Otto Ege‘s Portfolio of Famous Books in Nine Centuries (FBNC) which belongs to a Private Collection.

Our first post about that unnumbered Set first focused upon the Portfolio as an entity and then examined one of its specimen “Manuscript Leaves”:

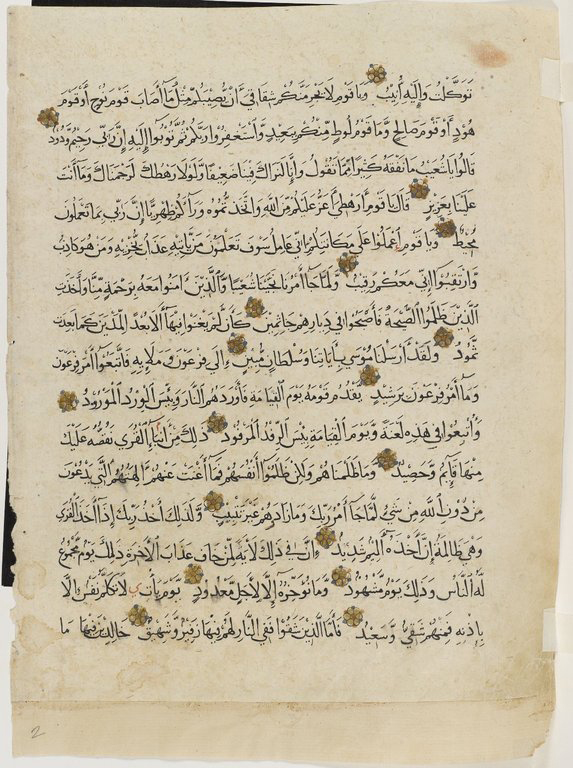

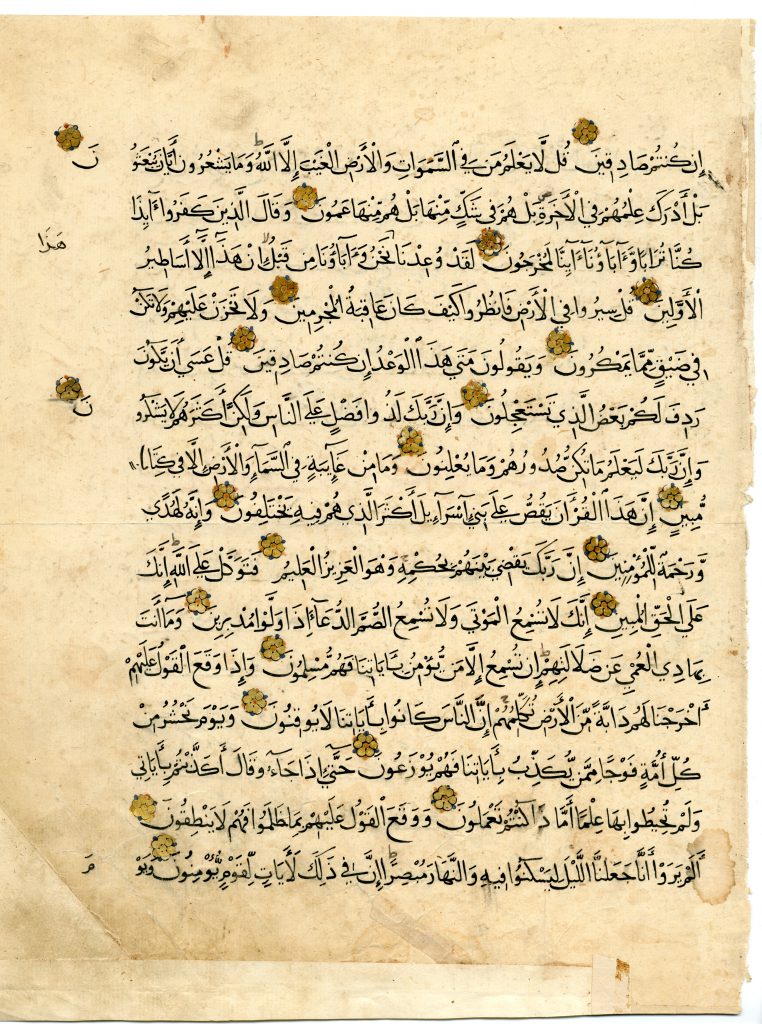

Known by its assigned number in Scott Gwara’s “Handlist” of Otto Ege’s Manuscripts (2016), that manuscript (seen at the right) represents the remnants of a dismembered Quran/Koran written on paper, late-medieval in date.

As the ‘Deluxe’ version of Ege’s Famous Books, the Portfolio in Nine Centuries was issued in 50 sets, with 40 specimen Leaves extracted from manuscripts and printed books. The shorter version in Eight Centuries was issued in 110 sets of 25 Leaves.

In earlier blogposts, as we examined various manuscripts and printed materials distributed by Otto Ege, some Sets in both versions of the Famous Leaves Portfolios have come into our direct view. See our Contents List.

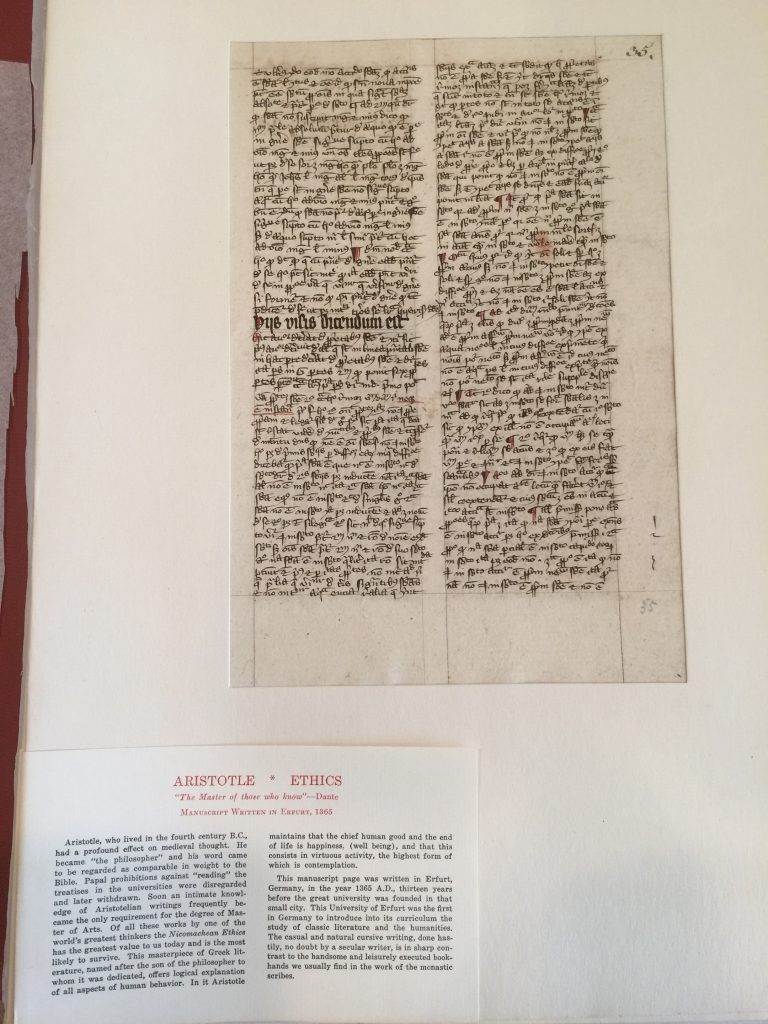

At first, mainly on account of the specimens from a 14th-century manuscript in Latin on paper with Aristotle’s Nichomachean Ethics and its commentaries or other texts. Our study of that manuscript (Ege Manuscript 51) began with an isolated leaf in a private collection, then moved to examine more of its relatives surviving elsewhere — particularly as more parts of the manuscript emerged into view, including the ‘residue’ or ‘carcass’ of one of its original 3 volumes.

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, Ege MS 51, Volume II, folio 1r, top left. Photography Mildred Budny.

Now, we continue the process of exploration by turning to more of the six Manuscript Leaves which open the Portfolio of Nine Centuries of Famous Books.

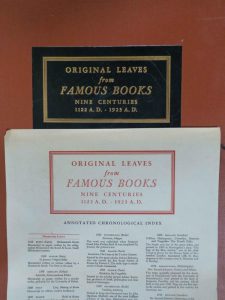

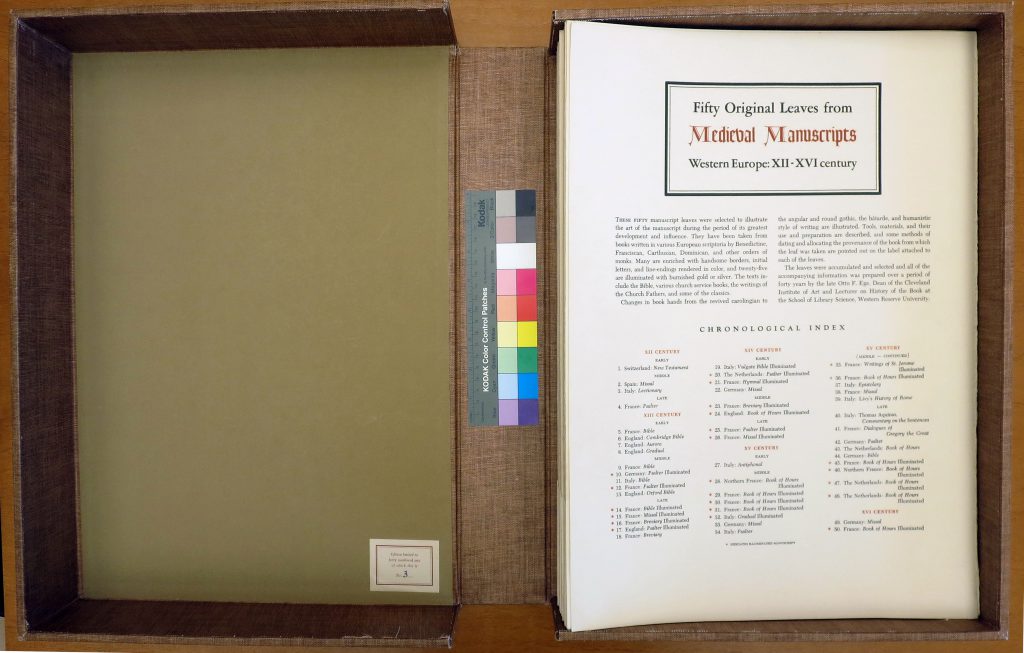

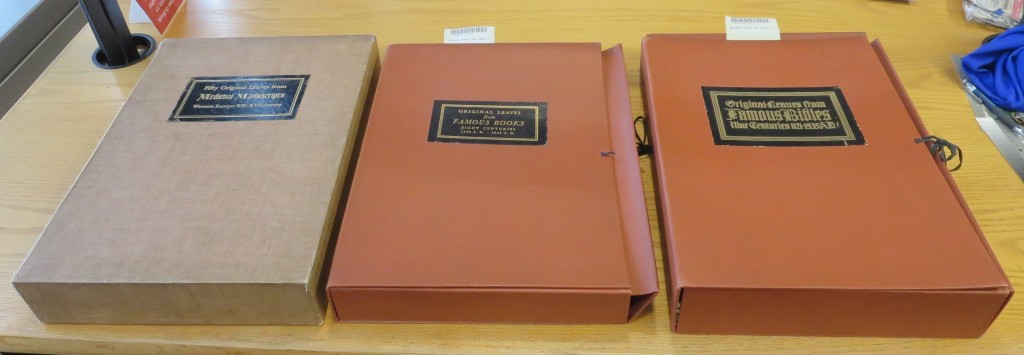

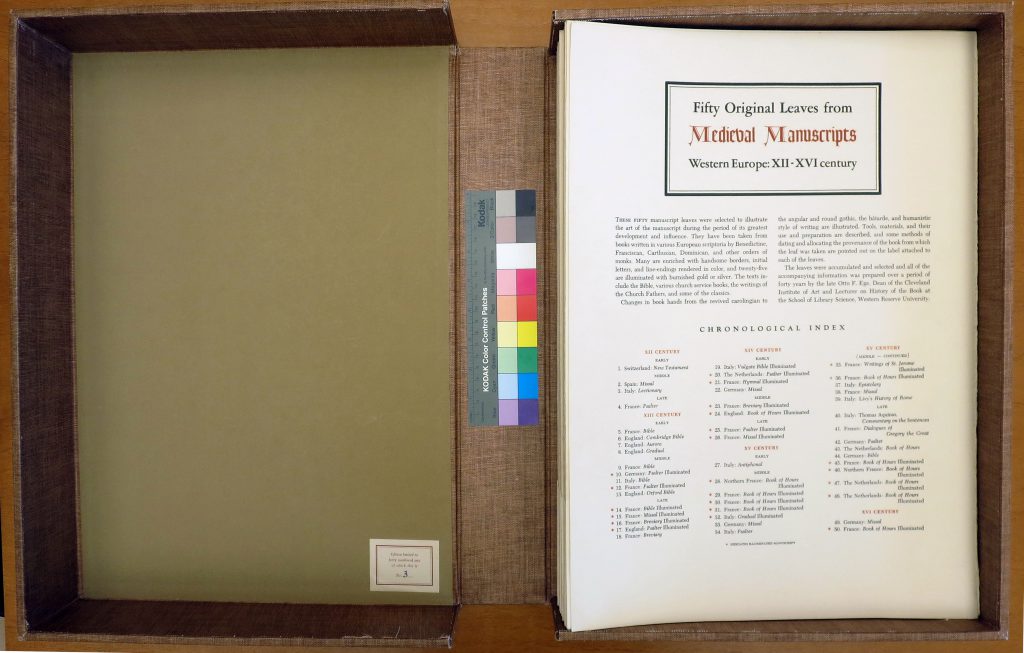

Famous Books in Nine Centuries

Bearing its title in a printed panel on the front, the Portfolio case encloses its group of specimens, individually framed within pairs of mat boards. They are accompanied by a full-page Contents List printed in red and black on a separate leaf.

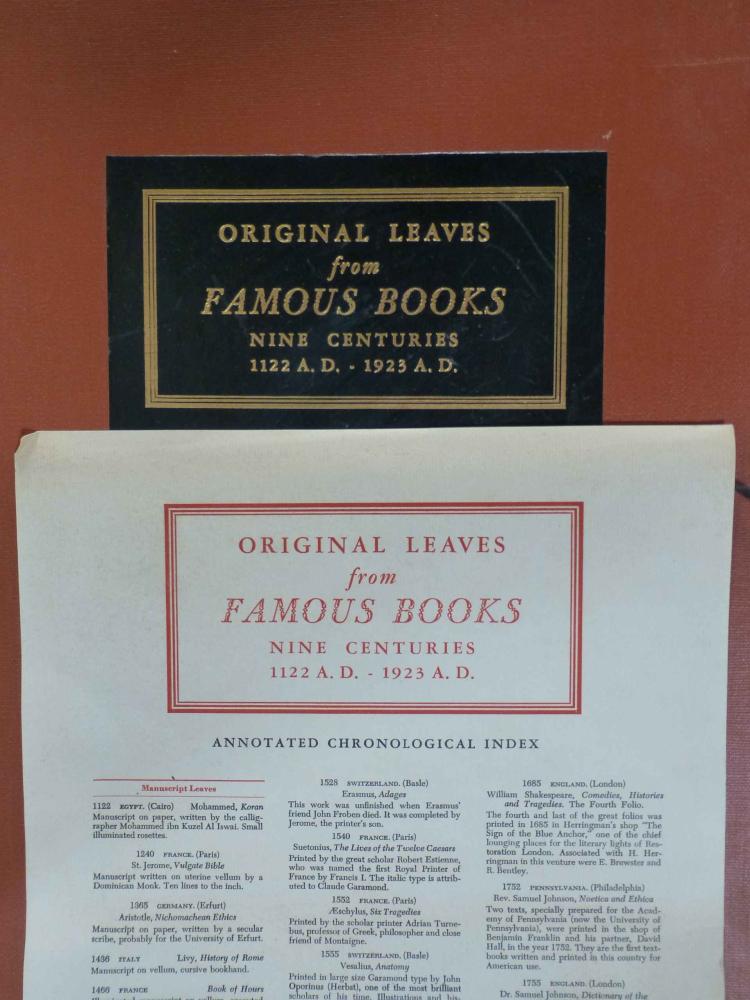

Private Collection, Ege’s FBNC, Title and Headpiece for the Contents List.

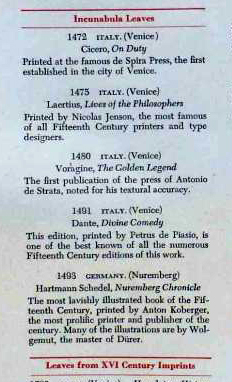

Private Collection, Contents List in Ege’s Famous Books in Nine Centuries, Chronological Index. Reproduced by permission.

Contents List and Specimen Leaves

Of uniform size, the pairs of mat boards have windows cut at the front to suit the different sizes of the specimens. A separate, full-page printed Contents List stands at the front of the group.

Ege’s “Annotated Contents List” in a single page stands as a loose leaf at the front of the Portfolio case.

The Portfolio gathers its specimen Leaves in a stack of individual framed mats, accompanied by their own printed Label.

As characteristic for Ege’s Portfolios, the mats present hinged pairs of boards. They combine a windowed mat at the front and a plain mat at the back, attached by hinged tapes at one side. The mats can be opened upon the hinges to reveal the individual specimen Leaf (sometimes, more than one Leaf) within its ‘sandwich’. The revealed Leaf might in turn might be lifted partly on its own hinged gauze tapes attached at one side, to show the other side of the leaf.

Their mats all have the same dimensions overall, so as to present a uniform group within the set. The back board is uncut. The window cut on the front board derives its specific size and shape in order to suit the specific specimen, albeit with a somewhat smaller opening than it. This approach produces the effect of some cropping at all sides, which masks the edges of the original.

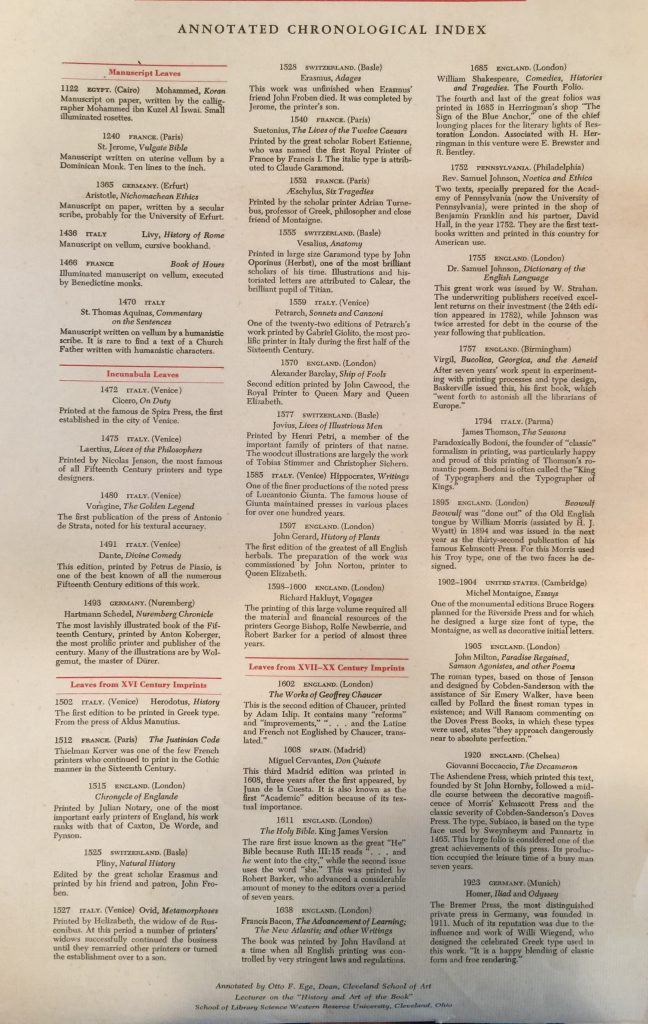

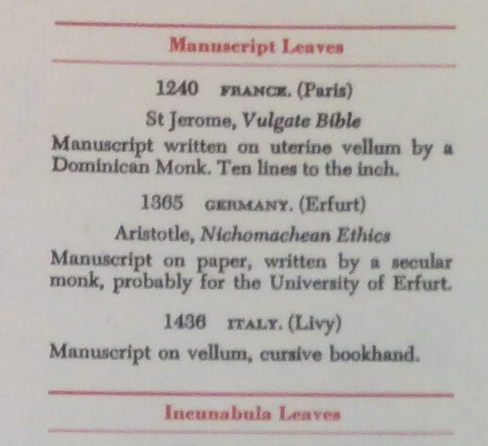

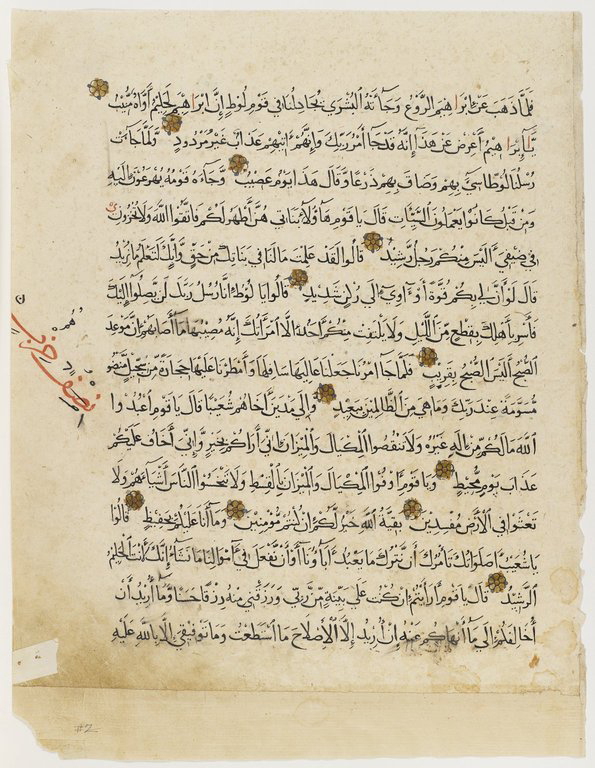

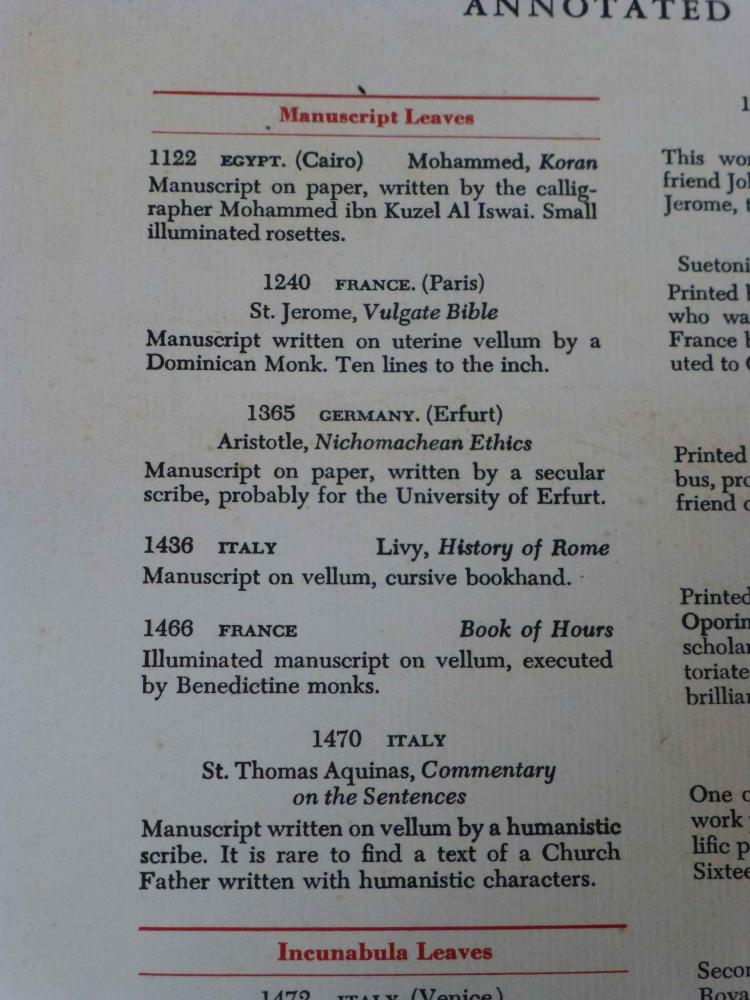

Contents List: Manuscripts and Other Texts

The Contents List groups its entries chronologically and by genre, identified by medium. They divide into 4 parts (let us call them Parts I–IV), starting with Manuscript Leaves (Part I) and moving on to printed materials spanning 5 centuries.

[Parts II–IV]. The Printed Leaves

After Part I, the groups in the Contents List and the other Specimens of the Portfolio exhibit printed materials. Arranged chronologically, they start with specimens of early printing in the West (“Part II”), and move onto later centuries (“Parts III and IV”). We consider these elements in other blogposts.

[Part I]. The Manuscript Leaves

The Manuscript Leaves form the first group of specimens in the FBNC Portfolio. The 6 varied specimens derive from manuscripts of different sizes, materials, types of texts, and styles of script, layout, and design.

Private Collection, Ege FBNC Contents List, Detail: Manuscript Leaves.

Our first blogpost on the Portfolio (Otto Ege’s Portfolio of Famous Books and ‘Ege Manuscript 53’) surveyed these 6 Manuscript Specimens, their assigned Handlist Numbers among Otto Ege’s Manuscripts (2016), and their representation and distribution in one or more Portfolios assembled by Ege. Namely, their specimens appear in one and/or another of these Portfolios:

- Original Leaves from Famous Books, Nine Centuries, 1122 A. E. – 1923 A. D. (“FBNC“), in the longer, Deluxe version,

with 40 unnumbered Leaves in 50 sets

- Original Leaves from Famous Books, Eight Centuries, 1240 A. D. – 1923 A. D. (“FBEC“),

with 25 Leaves in 110 sets

- Fifty Original Leaves from Medieval Manuscripts, Western Europe: XII–XVI Century (“FOL“),

with 50 numbered leaves in 40 sets

- Fifteen Original Oriental Leaves of Six Centuries: Twelve of the Middle East, Two of Russia, and One of Tibet (“Oriental Leaves“),

with 15 Leaves in 40 sets

To recap from our previous post:

The Manuscript Leaves in FBNC and their Ege Manuscript Numbers

[1]. Koran of ‘1122’ (CE) on paper (Ege MS 53)

— also in the Oriental Leaves Portfolio

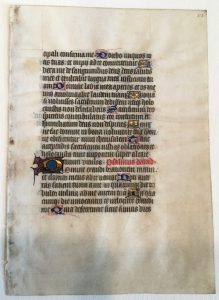

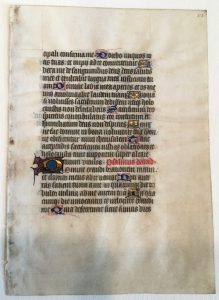

Private Collection, Ege’s Famous Books in Nine Centuries, Book of Hours Leaf, Front. Reproduced by permission.

(See Otto Ege’s Portfolio of Famous Books and ‘Ege Manuscript 53’)

[2]. Vulgate Bible of 1240 on ‘uterine vellum’ (Ege MS 54)

— also sometimes in FBEC (in alternation with Ege MS 9 of FOL)

[3]. Aristotle of ‘1365’ on paper (Ege MS 51)

— in both FBNC and FBEC

[4]. Livy of ‘1436’ (Ege MS 52)

— in both FBNC and FBEC

[5]. Book of Hours of ‘1466’ (Ege MS 55)

— only in this Portfolio of Nine Centuries (FBNC)

[6]. Aquinas of ‘1470’ or ‘Late XVth Century’ (Ege MS 40)

— also in FOL (Leaf 40)

Now we focus upon one of these Leaves and its manuscript context.

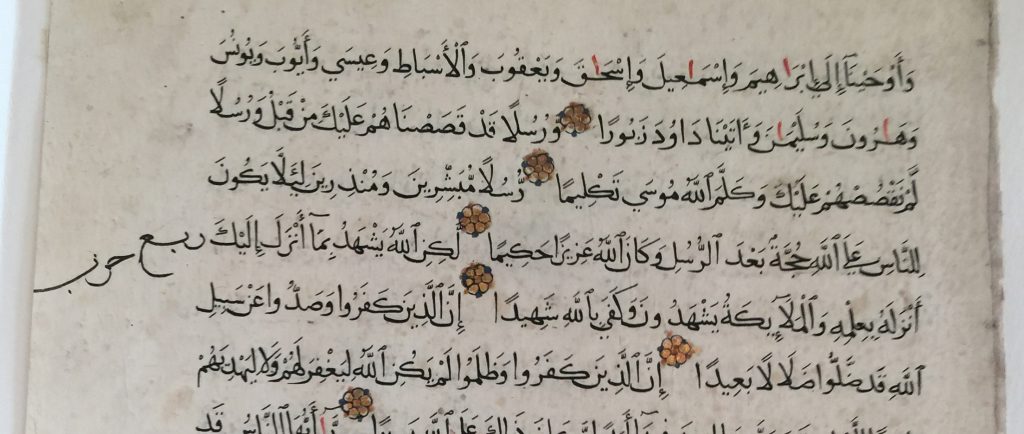

The Aquinas Manuscript in Humanist Script

We pick Specimen [6] from the Aquinas Manuscript (Ege MS 40), which ends the group of Manuscript Leaves in the Portfolio and finds a place also in FOL. To judge by its accomplished script, the manuscript must have been written somewhere in Italy within the sphere of humanist influence modeled upon examples of Carolingian Minuscules and of Capital Letters.

Private Collection, Ege’s FBNC Portfolio, Aquinas Leaf, Recto, Top Right. Reproduced by Permission.

The Author(s), the Text, and the Manuscripts

London, National Gallery, Demidoff Altarpiece, Detail: Thomas Aquinas. Panel painting by Carlo Crivelli (c. 1430/5 – c. 1494) for the Church of San Dominico at Ascoli Piceno. Image in the Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

To set the stage, we introduce some members of the cast. The principals are Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) and Peter Lombard (circa 1096 – 1160). Other agents, across the centuries, have had a hand in copying the text in humanist script from its exemplar, commissioning the work, transmitting the copy from collection to collection across time and space, bringing it to the United States, distributing its dismembered pieces, researching the distribution patterns, and examining the fragments in their new settings, as well as in their own right.

In his Labels, Otto Ege identified the leaves as pertaining to a copy in Latin of the Commentary by Thomas Aquinas upon Book I of the Sentences — a weighty text comprising 4 Books in all — composed in an earlier generation by Peter Lombard. By its very nature, the text of the commentary introduces Aquinas, Dominican friar, priest, philosopher, and theologian, posthumously to Peter Lombard, scholastic theologian and Bishop of Paris. Both came from origins in Italy (south and north respectively) to study and teach in Paris.

The text amounts to an indirect sort of dialogue, or a disputation, over distance and time, between 2 prodigious Christian authors, in which the younger and later one perforce has the last say. The text introduces its readers to Aquinas at a rather early stage in the formation and articulation of his deeply philosophical theology.

The Libri Quattuor Sententiarum (“Four Books of Sentences”) — Peter Lombard’s master work, composed circa 1150 — assembles a systematic compilation of theology which became a major textbook. It derives its name from the assembled sententiae, that is, “Sentences” or authoritative statements on biblical passages derived from the text of the Bible and texts by Church Fathers. Within the 4 Books, the author himself subdivided the material into chapters. Subsequently, many chapters were further subdivided, into “distinctions” (Distinctiones). The work served as a principal theological textbook for several centuries. Every master of theology was required to prepare a commentary on the Sentences, as part of the examination system.

Aquinas’s response to the assignment ascended to the stature of a textbook in its own right.

London, National Gallery, Demidoff Altarpiece, Detail: Thomas Aquinas. Panel painting by Carlo Crivelli (c. 1430/5 – c. 1494) for the Church of San Dominico at Ascoli Piceno. Image in the Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Peter Lombard’s Sentences

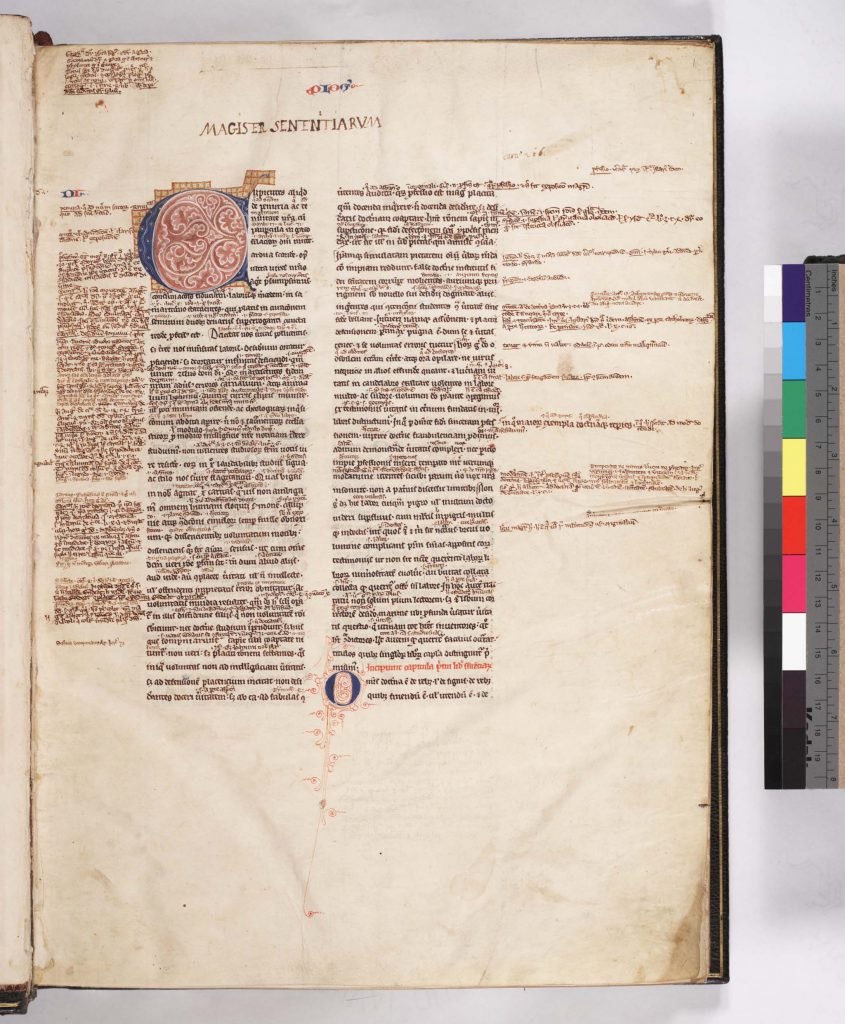

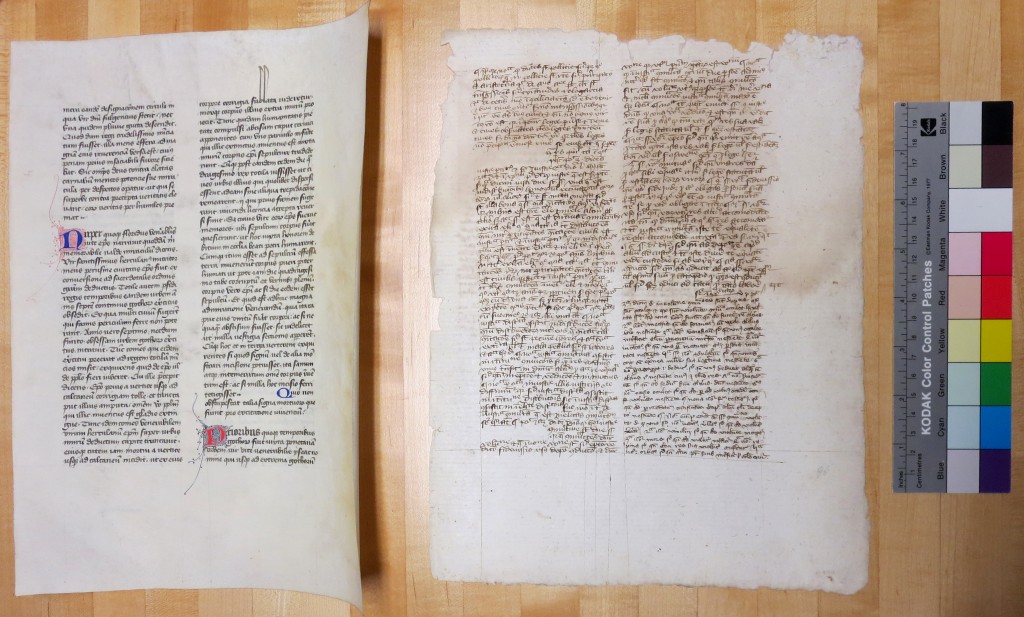

In one of its 14th-century copies, the opening page of the Book of Sentences by Peter Lombard looks like this.

Free Library of Philadelphia, Rare Book Department, Lewis E 170, fol. 1r, Opening the Book of Sentences, via http://libwww.freelibrary.org/medievalman/Detail.cfm?imagetoZoom=mca1700011

Laid out in double columns, the text has titles for sections, decorated initials for sections, and running titles, as aids for orientation. The wide margins offer, as intended, expansive scope for additions. Many comments, or glosses, by different hands are densely placed both in the margins around the columns and between the lines of text.

Remember, Aquinas encountered the source text in one or more manuscript copies. They – as well as his own – may well have held such forms of visual ‘dialogue’ or ‘argument’ between the main text and its comments.

Aquinas’s Commentary on the Sentences

Studies of Aquinas and his large body of work abound, not least because of the breadth, scope, and impact of his intellect and output. Reference materials for approaching the work or works appear in such sites as the guide to Thomas Aquinas in English: A Bibliography.

Aquinas’s commentary on Peter Lombard’s textbook, the Scriptum super libros Sententiarum (“Writing on the Books of the Sentences”), stands securely within the development or evolution of his own monumental oeuvre. About this Commentary, the circumstances of its composition, and its approach, a brief summary might set the stage. For example, according to the Aquinas Institute,

The Commentary on the Sentences dates from St. Thomas’s first teaching years in Paris, where he began teaching around the year 1252. As a new teacher, St. Thomas was expected to prepare lectures based on the Sentences of Peter Lombard, thus demonstrating his knowledge of and insight into both theology and philosophy. In the Sentences, St. Thomas was presented with a general theology text which draws upon the writings of the Church Fathers. This was a significant opportunity for St. Thomas to delve into the beauty of theology. Although this text is a commentary on the Sentences, it also contains much original theological thought of St. Thomas himself as he departs at times from the text that he is commenting on to explore other facets of the teaching set forth by Peter Lombard. As this work comes from the earlier years of St. Thomas’s career, it is evident that it represents St. Thomas’s seminal theological thought that is later developed and sharpened in the Summa Theologiae and the Summa Contra Gentiles.

— Sentences Commentary.

The Texts, Editions, and Translations

Among freely available editions online, examples include:

1. The Sentences by Peter Lombard in Latin

A translation of the full work in English:

- Peter Lombard, The Sentences, Books 1–4. translated by Giulio Silano (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 4 vols., 2007–2010).

Book 1: The Mystery of the Trinity

Book 2: On Creation

Book 3: On the Incarnation of the Word

Book 4: On the Doctrine of Signs

2. The Commentary by Aquinas on those Sentences in Latin

Liber I in particular, on “The Mystery of the Trinity”

The Commentary rendered in English

Parts of the text have received, or are receiving, English translations. Online translations and studies of the text include:

Private Collection, FBNC Aquinas Leaf in Mat with Label. Reproduced by permission.

Surviving manuscript copies of Aquinas’ Commentary on Peter Lombard’s Sentences include an specimen of about half of the Commentary on Book IV. Made in France circa 1460, it is laid out in columns of 34–41 lines and written in Gothic scripts. It amounts to 350 folios.

Such a book might be the sort of copy of Aquinas’ Commentary (or part of its 4 Books) prepared at about the same time as the Aquinas Manuscript in Humanist Script, but in a different region practicing late-medieval styles of script and book-production as yet untouched by a revivalist approach to ‘antique’ and classicizing precedents.

Book I of the Commentary

Aquinas’s Book I follows the order in the Sentences, guiding an exploration of the Trinity. The text takes shape in a series of Distinctions (customarily numbered 1–48). It examines the unity of God, the generation of the Son, and the “proceeding” of the Holy Spirit; considers the equality of the Persons in the Trinity; discusses ways in which God can be known; and relates an understanding of predestination and Divine Will, with a view to eternity.

Ege’s Labels for the Aquinas Manuscript

Ege’s Labels for the specimens of the manuscript take different forms. Not only do they focus upon different aspects of the text, script, and other features, but also, curiously, they report a different date or a date-range for the manuscript. The differences are reflected in the transmitted reports or records of the dismembered and differently distributed parts.

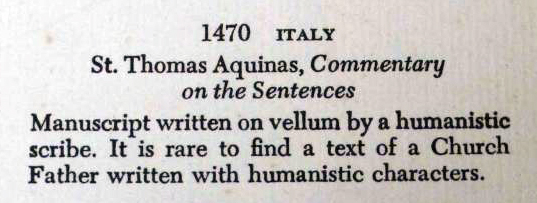

1. The Contents List for the Famous Books in Nine Centuries

The Contents List describes the item simply, and gives a precise date.

Private Collection, Ege’s FBNS, Contents List, Detail: The Aquinas Manuscript. Reproduced by permission.

Thus:

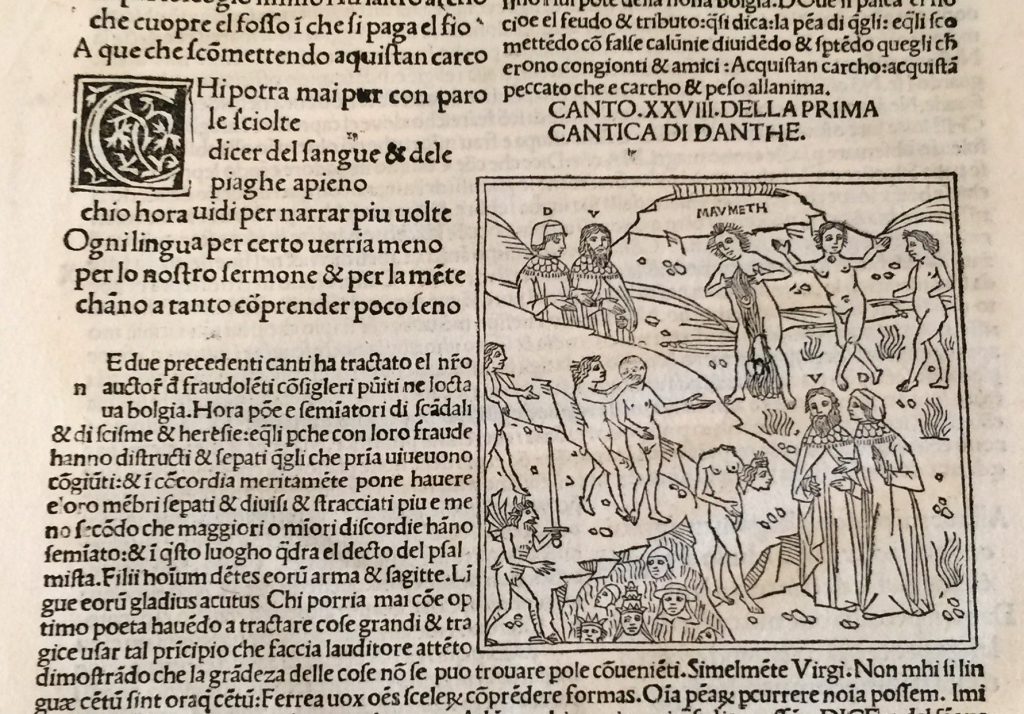

1470 Italy

St. Thomas Aquinas, Commentary

on the Sentences

Manuscript written on vellum by a humanistic

scribe. It is rare to find a text of a Church

Father written with humanistic characters.

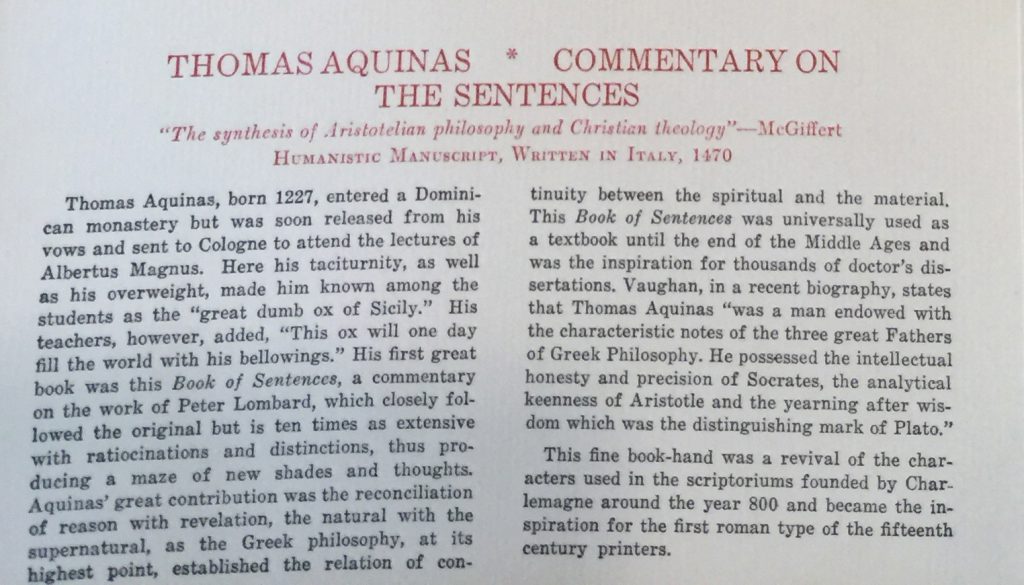

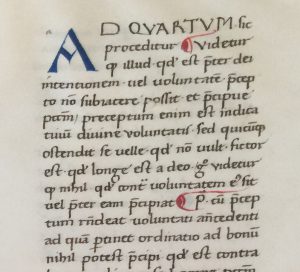

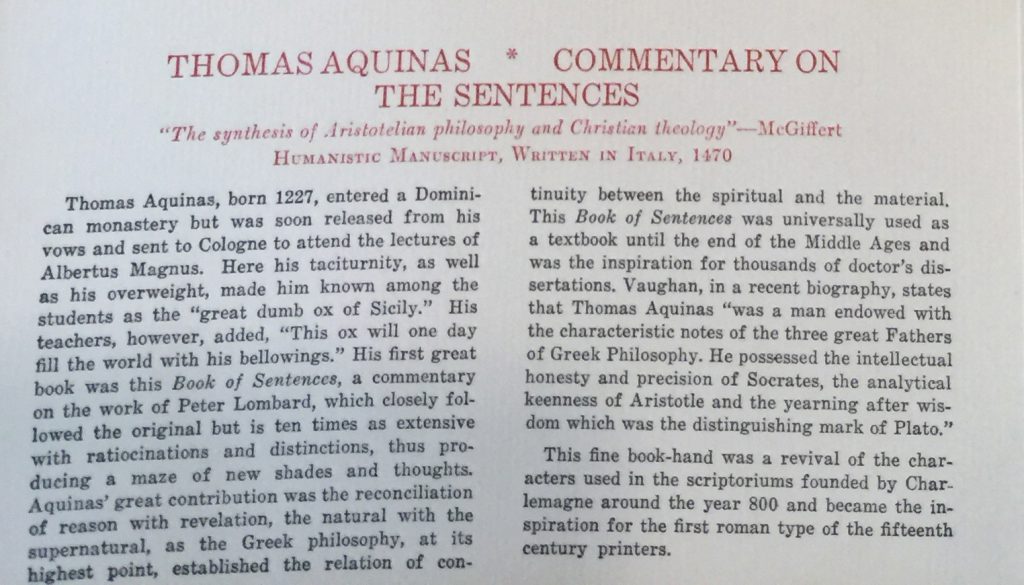

2. The Label for the Leaf in the Famous Books Portfolio

Ege’s Label for the manuscript in the Famous Books Portfolio (FBNC) states the case more elaborately. The Label takes the form of a separate rectangular strip of paper, pasted at the back of the frame and folded around the windowed mat at the lower left. The terms of the Label consider the nature of the text and the authorial genius of the author at some length, before turning to a concluding paragraph about the type of script, its inspiration in early-medieval Carolingian models, and its impact upon early printing in the West.

Again, the assigned date takes the precise form of 1470 — tout court. In the form of a motto below the title of the work, the 1-line quotation from a “recent” biography of the author (attributed to “McGiffert”, or Arthur Cushman McGiffert) adds a smidgen of adulation.

Private Collection, Ege’s Famous Books in Nine Centuries, Label for the Aquinas Manuscript Leaf. Reproduced by permission.

The Label states:

THOMAS AQUINAS * COMMENTARY ON THE SENTENCES

“The synthesis of Aristotelian philosophy and Christian theology” — McGiffert.

Humanistic Manuscript, written in Italy, 1470

Thomas Aquinas, born 1227, entered a Dominican monastery but was soon released from his vows and sent to Cologne to attend the lectures of Albertus Magnus. Here this taciturnity, as well as his overweight, made him known among the students as the “great dumb ox of Sicily.” His teachers, however, added, “This ox will one day fill the world with his bellowings”. His first great book was this Book of Sentences, a commentary on the work of Peter Lombard, which closely followed the original but is ten times as extensive with ratiocinations and distinctions, thus producing a maze of new shades and thoughts. Aquinas’ great contribution was the reconciliation of reason with revelation, the natural with the supernatural, as the Greek philosophy, at its highest point, established the relation of continuity between the spiritual and the material. This Book of Sentences was universally used as a textbook until the end of the Middle Ages and was the inspiration for thousands of doctor’s dissertations. Vaughan, in a recent biography, states that Thomas Aquinas “was a man endowed with the characteristics notes of the three great Fathers of Greek Philosophy. He possessed the intellectual honesty and precision of Socrates, the analytical keenness of Aristotle and the yearning after wisdom which was the distinguishing mark of Plato.

This fine book-hand was a revival of the characters used in the scriptoriums founded by Charlemagne around the year 800 and became the inspiration for the first roman type of the fifteenth century printers.

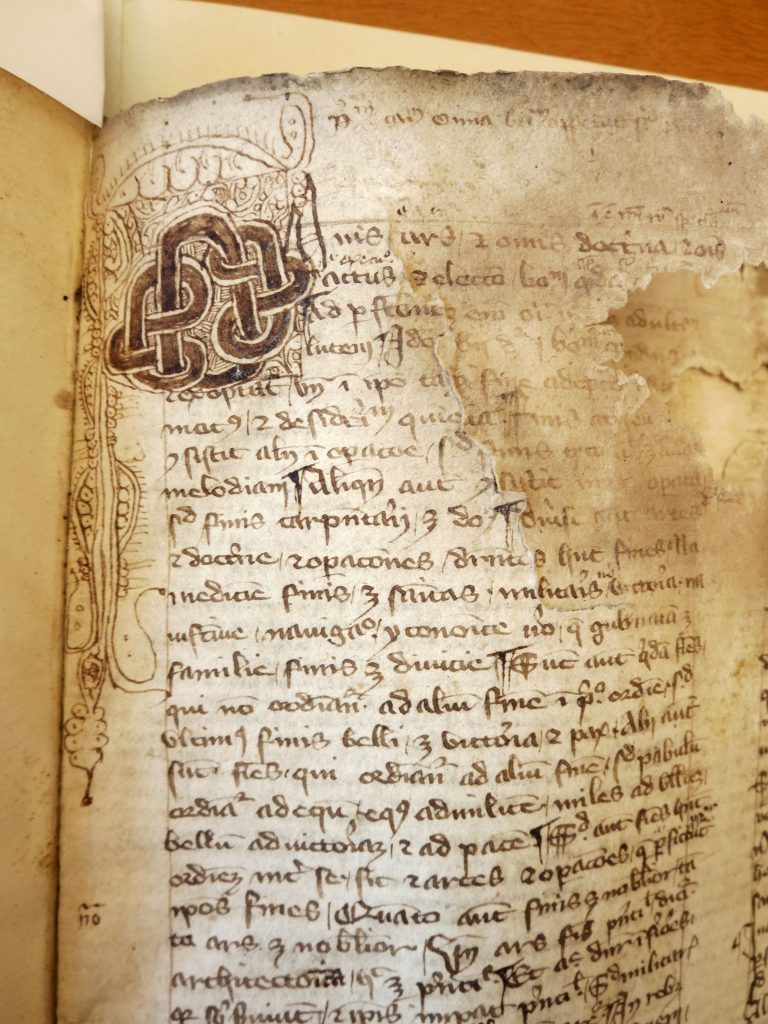

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, MS 40, Specimen 2 = folio 216v (turned to the front in Ege’s Mount): Top of Textblock. Photography Mildred Budny.

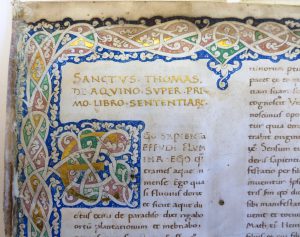

3. The Label for the Leaf in the FOL Portfolio, with Ege’s Manuscript Number 40

Ege’s Label for the specimens from the Aquinas manuscript in his Portfolio of Fifty Original Leaves from Western Manuscripts, Western Europe, XII–XVI Century (FOL) takes a more compressed approach, and focuses upon the script. In this case, the Label fudges about the assigned date, reported as “Late XVth Century”.

As with the Labels for the other manuscript specimens in the FOL Portfolio (but unlike the unnumbered Labels for the FBNC Portfolio), the Number assigned to the Leaf in the sequence on the Contents List is printed at the top right. The Label for Number 40 states the case thus:

Otto F. Ege: Fifty Original Leaves from Medieval Manuscripts, Leaf 40, Printed Label, Special Collections and University Archives, Stony Brook University Libraries.

That is, under the headings of “ITALY; Late XVth Century” and “Latin Text; Humanistic Book Hand”, the Label introduces the specimen in the terms focusing upon the script and its unusual use for such a non-secular text.

Thomas Aquinas, Commentary on the Sentences

(Super Primo Libro Sententiarum)

FROM THE COLLECTION OF OTTO F. EGE

This text on the Sententiae of Peter Lombard by St. Thomas Aquinas, the “Angelic Doctor,” was the forerunner of the latter’s great work Summa Theologica. It is most unusual to find the writings of a Church Father presented in a humanistic book hand. Some of the humanists called this form of writing antiqua littera, with reference to the carolingian script, which they mistook for that of antiquity. In this humanistic script, fusion disappeared, letters became more simple, and shading decreased. The first more or less humanistic type of writing appeared in Florence about 1400 A.D.

A Specimen from the manuscript in a Set of the FOL Portfolio at Harvard University:

Harvard University, Harvard University, Houghton Library, MS Typ 995, recto = Ege MS 40, folio 243 recto.

4. The Contents List for the FOL Portfolio

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, with Case opened to Inside Front Cover and the Contents List. Photography Mildred Budny.

The full-page Contents List for the FOL Portfolio lists Leaf Number 40 within the “LATE” grouping for the “XV Century”. Its listing names only the Country, Author, and Text:

40. Italy: Thomas Aquinas, Commentary on the Sentences.

It appears that the ‘rules’ for this “CHRONOLOGICAL INDEX”, grouped by centuries with subdivisions into “EARLY”, “MIDDLE”, and “LATE”, governed the omission of more specific dates for cases where they might have been known.

While we survey Ege’s several approaches, it is important to note another form of description which he adopted for some leaves intended for sale separately.

5. The Leaves in the 1944 Staff Loan Catalogue (Lima, OH)

Prepared in support of the Lima Public Library Staff Loan Fund, Lima, OH, the 1944 Staff Loan Catalogue offered for sale numerous Original Leaves & Sets of Leaves from Medieval Manuscripts, Incunabula, Famous Bibles, and Noted Presses, 1150 A. D. – 1935 A. D. The catalogue appeared in a stapled booklet of 15 printed pages, with a cover page announcing that title and related information.

A rare surviving copy of the Catalogue, mailed to Alexandria, Minnesota, and bearing a postmark of 1944, is reproduced in part in Scott Gwara, Otto Ege’s Manuscripts (2016), figures 41–48 on pages 253–260 (showing pages 1–5 and 14–15 of the Catalogue). See also pp. 41–48 and 208, as well as p. 40 and note 97.

The Catalogue lists some leaves from the Aquinas manuscript (Ege Manuscript 40 = Handlist number 40) in 2 different sections. In both cases, the items within sets containing leaves from several different books.

First:

- Set of 18 Leaves, The Book Beautiful through Nine Centuries (pages 1–2 in the Catalogue; Gwara, figure 42 on p. 254)Within this “Superb Set”, for the price of $100.00, the Aquinas Commentary joins 6 manuscripts as well as multiple printed items. It appears as

[Item 1.] (f): 1470 A.D. ITALY. St. Thomas Aquinas’ Commentary. Fine humanistic bookhand with fine illuminated letter.

Second:

Sets of Leaves from Medieval Manuscripts, listed as 3 groups, numbered as Sets 9–11 (Pages 4–5 in the Catalogue; Gwara’s figure 46 on page 258). For the sets, “All leaves are matted and enclosed in portfolios”.

The Aquinas Commentary appears in Set 10 (for $25.00), as its item 6.

[Set] 10. Eight Original Manuscript Leaves from the 12th to the 16th Centuries

[Item] (6) 1470 A.D. Italy. St. Thomas Aquinas’s Commentary on the Sentences.

In each case, the cited date for the manuscript conforms with the precise version presented in the Labels for the Famous Books Portfolio, rather than for the FOL Portfolio.

Variable, and Indicative (or ‘Diagnostic’), Terms for the Leaves

Ege’s variability in the presentation of information circulating with the different dispersed leaves not only might generate frustration from the obfuscation. But also they can, in some cases, provide useful clues for the specific patterns of transmission beyond his collection.

In combination, conflation, or diversion, Ege’s several approaches to the Labels for the manuscript provide scraps of evidence or information about the manuscript as it came to him, about its features as they appeared to him, and about the way(s) in which he came to understand it as he worked to separate its leaves from each other and to scatter them widely into different hands, both public and private.

‘Diagnostic’ Terms for the Distributions of Leaves

Because Ege’s provisions of information for the individual leaves about to be dispersed in various ways were themselves so variable, it can be helpful to pay attention to the terms themselves in Ege’s Labels and handwritten annotations.

The variability may partly have arisen as Ege’s understanding of the manuscript materials deepened or extended, with changes or refinements in such aspects as the assignments of dates or date-ranges. But it must have resulted in no small measure from the varieties in approach to reporting and recording salient information pertaining to the manuscripts as wholes. Encountering that remission requires careful attention to the specific terms and forms of description which Ege employed at different times for the materials emanating from a single manuscript.

Such care can repay effort, as the terms which travel with a given manuscript specimen sometimes serve as indirect, and occasionally clear, evidence for the method by which that specimen left Ege’s hands, workshop, and collection.

An example is demonstrated in More Discoveries for ‘Otto Ege Manuscript 61’. A sales ‘clipping’ which travelled with one of its leaves, and which happily remained in view within an uncropped image of that leaf (as sent to me by its institution for higher quality resolution for reproduction), goes far to show that the leaf departed through the 1944 Sale Catalogue.

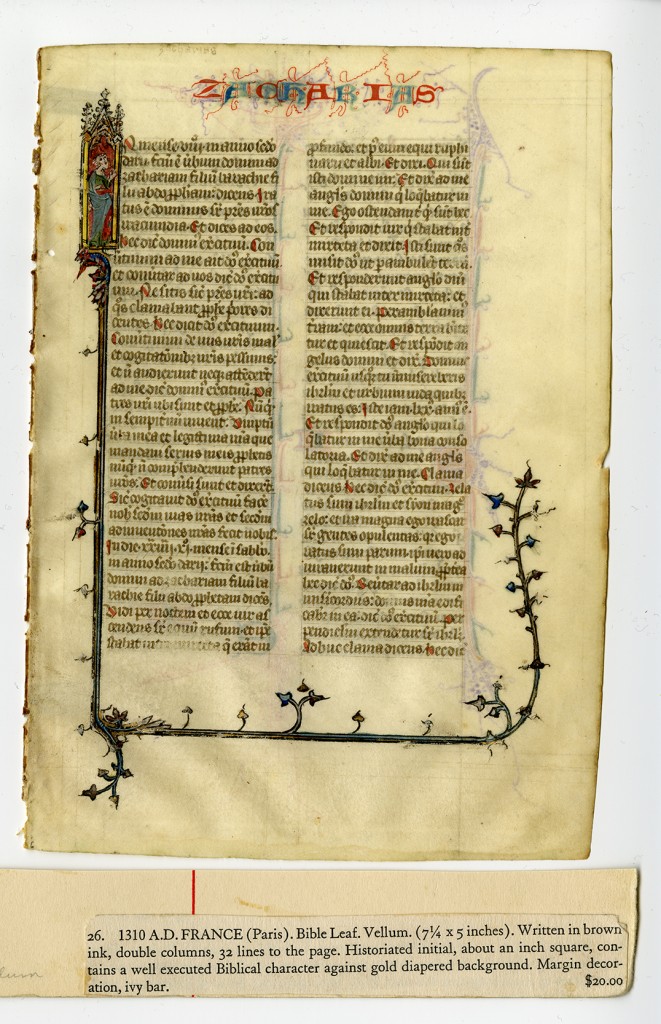

The clipping focuses upon Item 26 on page 7 — reproduced in Gwara, Otto Ege’s Manuscripts, figure 43 (page 255). The clipping of the printed item, including its number, is still attached to the surviving cropped segment of Ege’s characteristic ivory-colored mat, ruled in vermilion framing lines, with which the leaf came to its collection.

Recto of Leaf Opening the Book of Zachariah, plus Clipping from its Sale Catalogue. Courtesy of Flora Lamson Hewlett Library, Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, CA. Reproduced by permission.

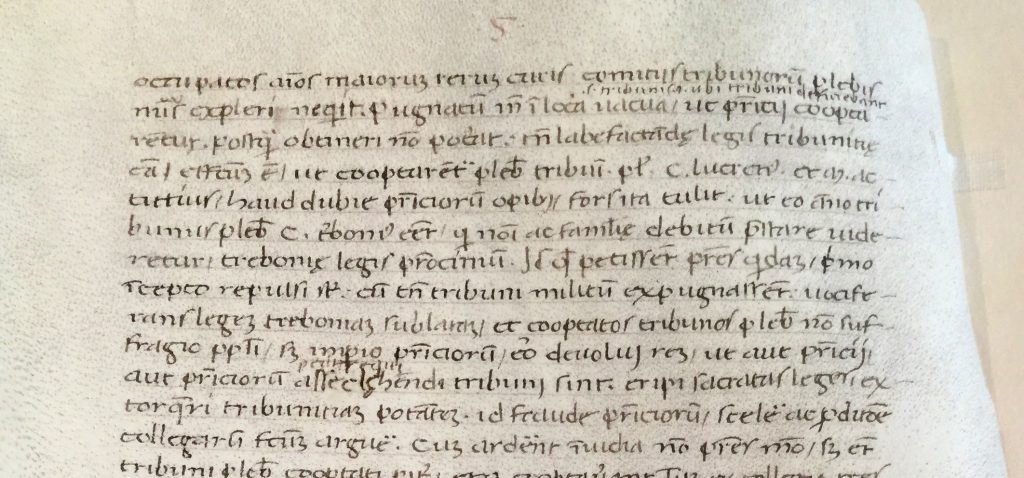

The ‘New’ Leaf from the Aquinas Manuscript in Humanist Script

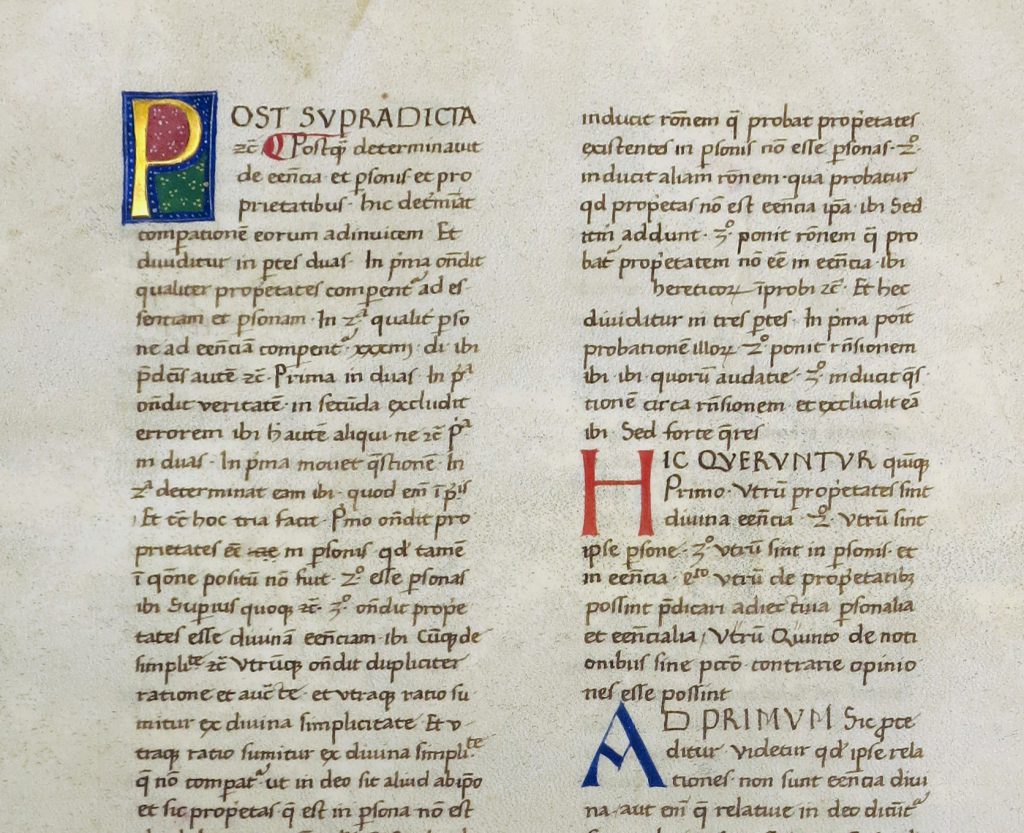

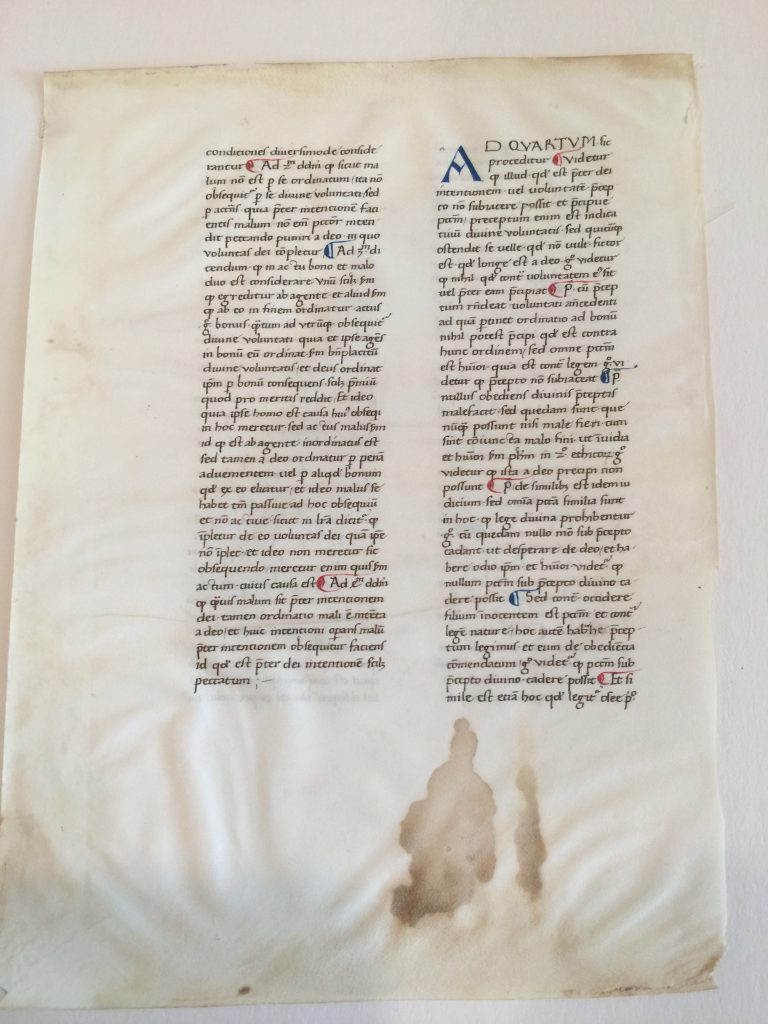

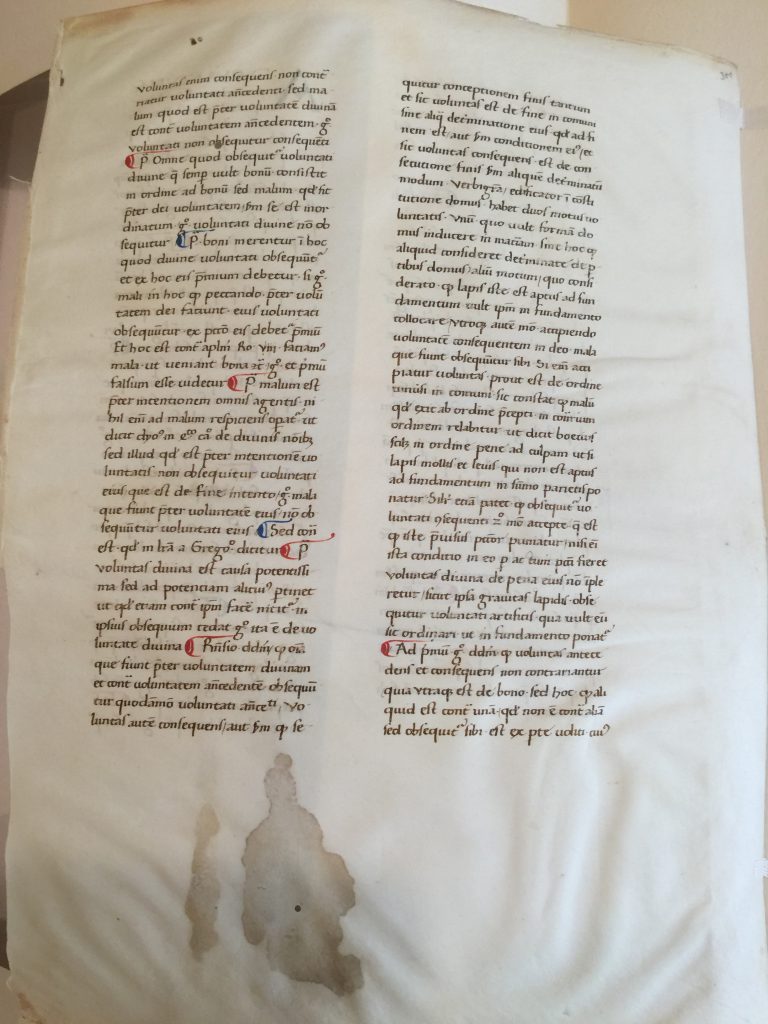

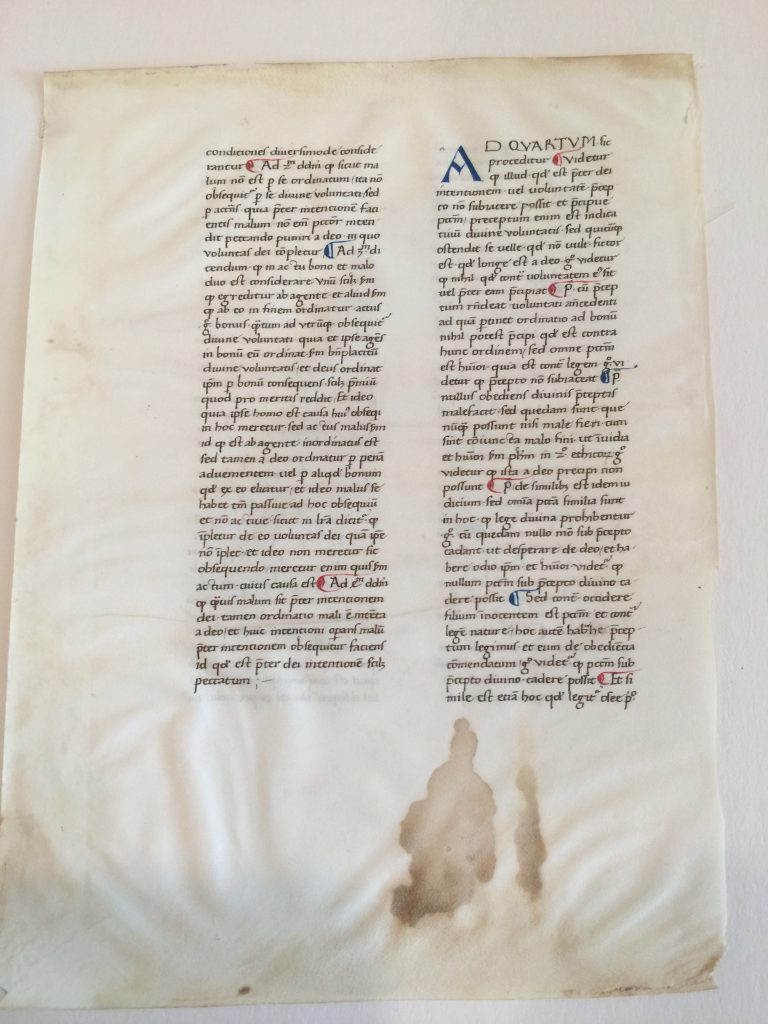

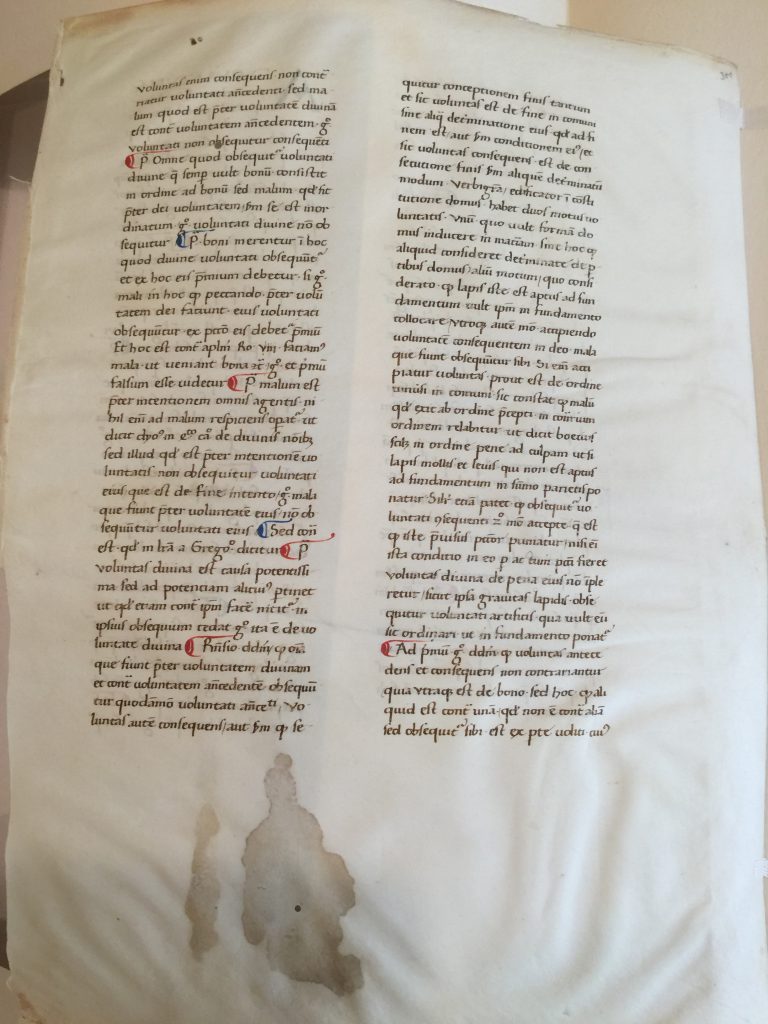

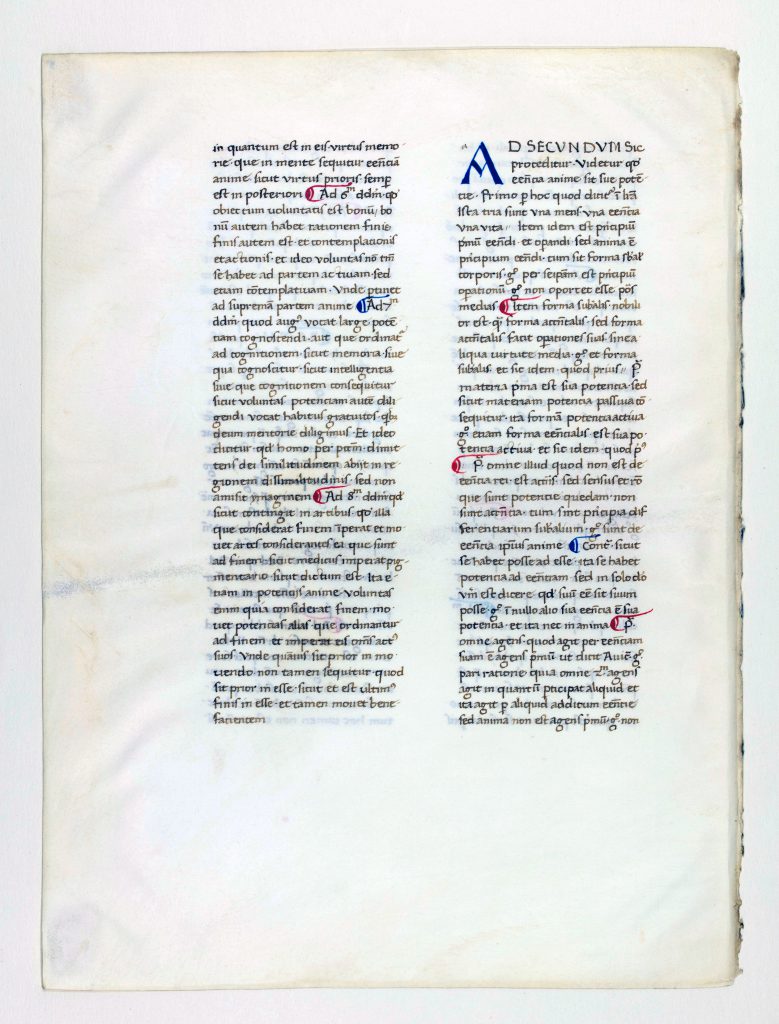

The text combines, or interlinks, segments of discourse by Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) and Peter Lombard (circa 1096 – 1160). The leaf forms part of Aquinus’ Commentary on the Sentences of Peter Lombard, Book I, dedicated to ” The Mystery of the Trinity”. Laid out in double columns of 37 lines, the script appears to date to circa 1475. The leaf forms part of Ege MS 40, listed in Gwara, “Handlist” = Otto Ege’s Manuscripts, Appendix X, pages 131–132, at pages 131–132.

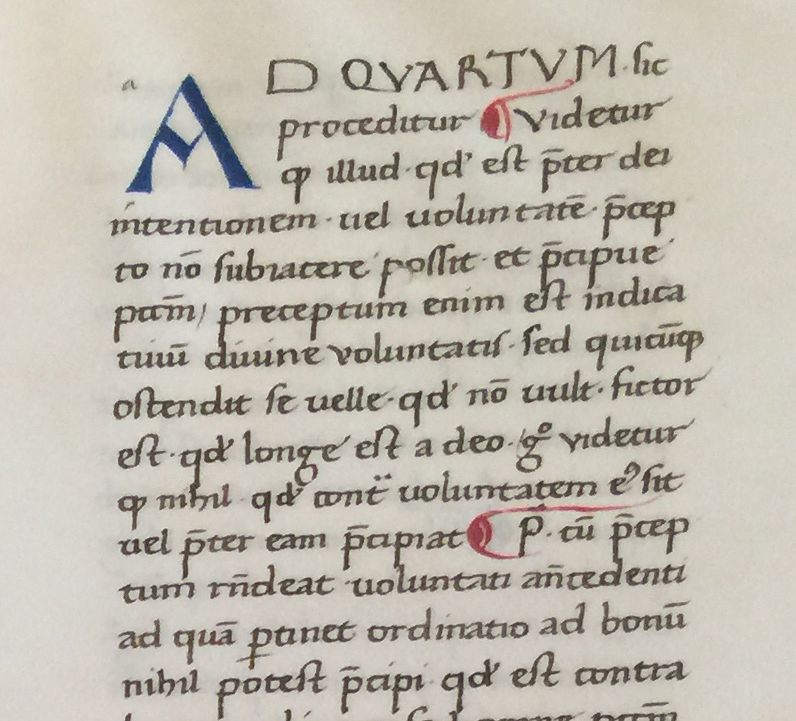

This ‘new’ Specimen Leaf has the pencil number 300 at the top outer corner on the ‘verso’ of the leaf, as Ege mounted it, turning back to front so as to display the opening initial for a new section.

The Leaf stands seemingly cropped within Ege’s mat, with Ege’s printed Label attached to the lower left at the front of the mat.

Private Collection, FBNC Aquinas Leaf in Mat with Label. Reproduced by permission.

The ‘front’ of the Leaf, as revealed below the lifted front of the windowed mat:

Private Collection, FBNC, Aquinas Leaf ‘Recto’. Reproduced by permission.

Note that it is the original verso of the leaf, with the wider outer margin positioned at the left.

The large dark stains from some liquid spills in the lower margin form a couple of irregular ‘pools’ which stand side-by-side. The effects of moisture along the bottom edge have cockled the vellum when drying unstretched. A few dark stains affect the lower outer edge, with some losses along the outer corner.

Dark stains from dirt and perhaps also moisture falling from the top of the book extend across the upper edge. Presumably they were shared by adjacent parts of the closed volume in vertical storage of some sort.

To reveal the ‘back’ of the Leaf, it is possible to lift it partly away from the back mat, to which it is attached by a pair of Ege’s gauze mounting tapes.

Private Collection, FBNC, Aquinas Leaf ‘Verso’. Reproduced by permission.

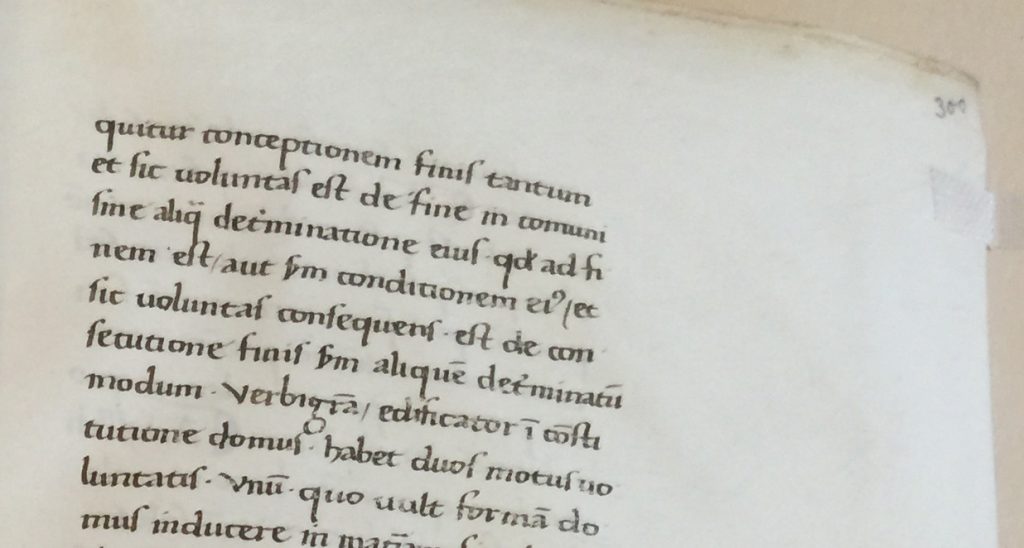

With the outer margin positioned at the right, the folio number emerges into view. In the top corner, the modern pencil number ‘300’ rises at a diagonal to the right.

Private Collection, FBNC, Aquinas Leaf ‘Back’ top right and page number. Reproduced by permission.

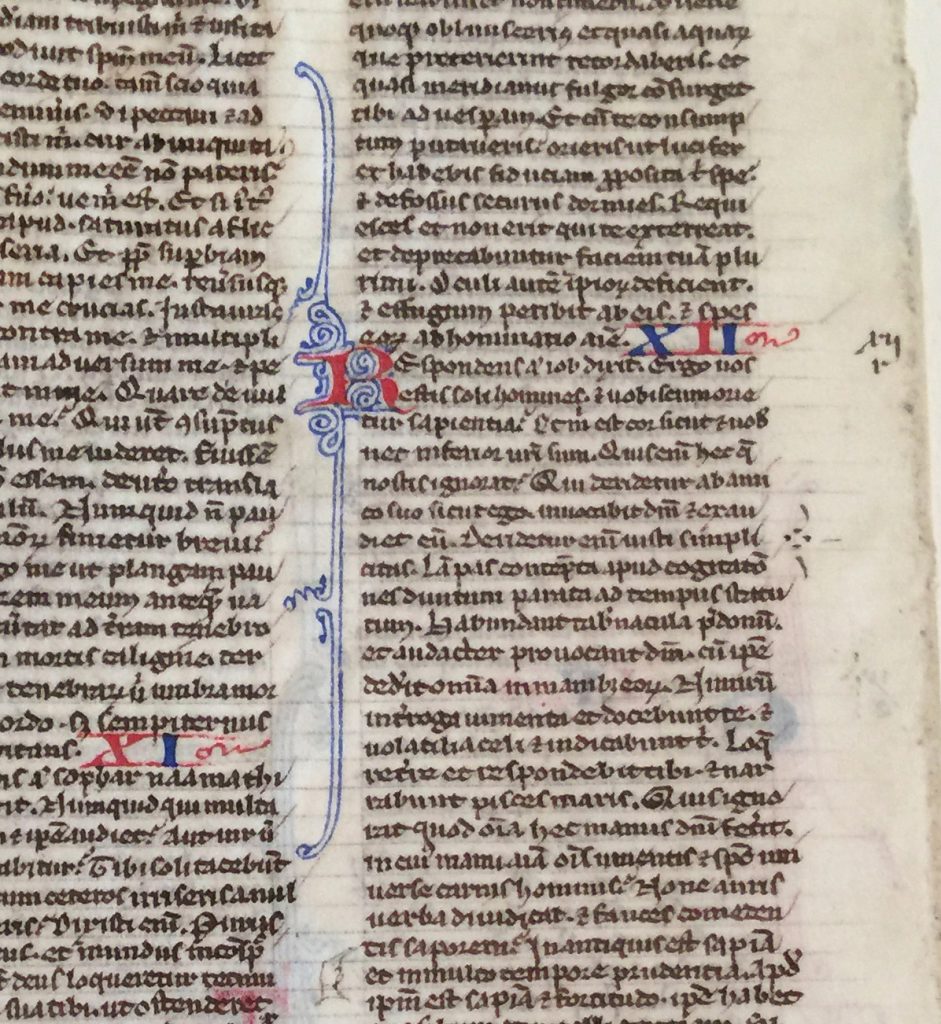

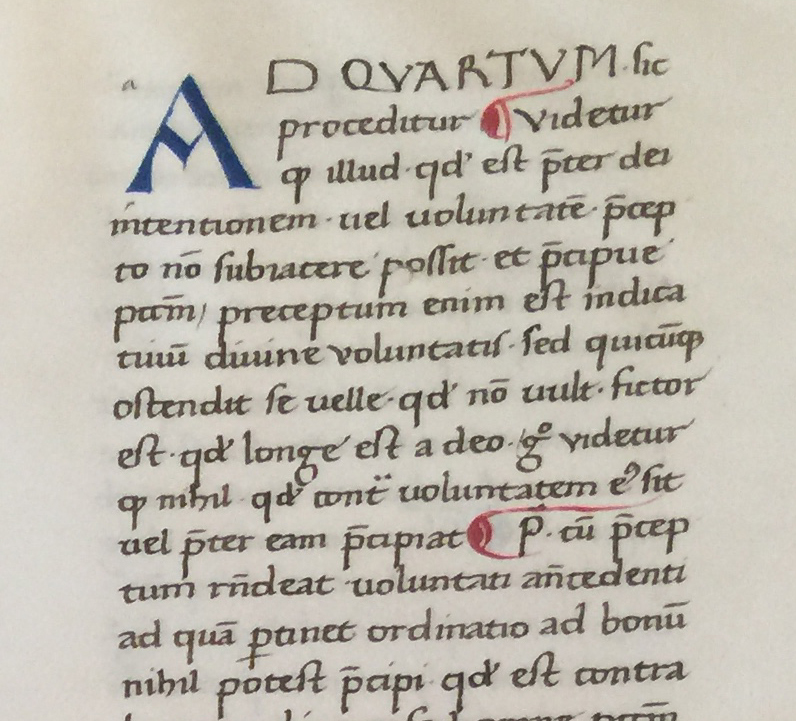

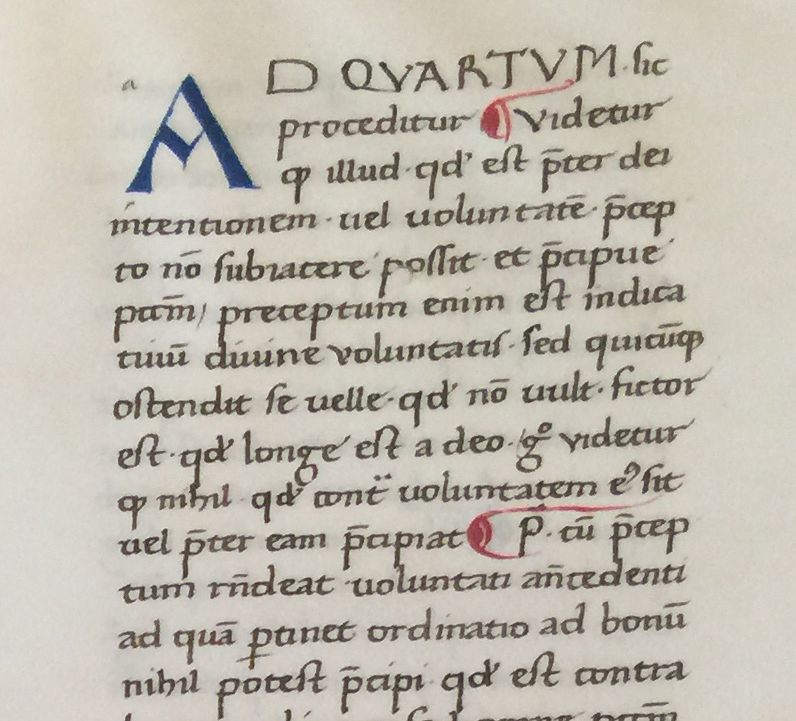

An opening section of text with an enlarged initial stands at the top of column b on the original verso; it was this side that Ege turned to the fore in his windowed mat.

Private Collection, Ege’s FBNC Portfolio, Aquinas Leaf, Recto, Top Right. Reproduced by Permission.

The heading begins with an inset 3-line initial A (for Ad, “To” or “Toward”) rendered in blue pigment. Written discreetly in ink, a small cue letter a stands to its left, as a prompt for the letter when the time came to add the initial in color, after the script in ink had been entered. A paraph-marker in red pigment fits within line 2, between the heading (AD QVARTUM sic proceditur) and the opening of the section (Videtur quod . . . ).

Ad quartum sic proceditur.

Videtur quod id quod est praeter Dei voluntatem, praecepto non subjaceat, et praecipue peccatum. . .

Within the Commentary on Book I of the Sentences, this passage corresponds to the opening of Distinctio 47, Quaestio 1, Articulus 4, Argumentum 1.

= Super Sententiis, Liber I, Distinctio 46, Quaestio I, Articulus 4, Argumentum

Or, “On the Sentences, Book I, Part (Distinctio) 46, Question I, Article 4, Argument 1″

For short: [3345] “Super Sent., lib. 1 d. 47 q. 1 a. 4 arg. 1”

— as marked out in the freely available edition online: www.corpusthomisticum.org/snp1045.html, numbering the individual sections with a series of consecutive arabic numbers (which I emphasize here in bold).

Although not specified as such in this manuscript, the subject or summary of the section is known as

Utrum id quod est praeter voluntatem Dei praecepto non subjaceat

Might the blank line or so at the end of column a have been intended to hold the title or summary for the section, in enlarged and perhaps rubricated form? To read, perhaps, something like this?

Articulus IV: Utrum Deus velit mala fieri.

On its own, the leaf does not reveal whether that skipped last line in the column was designed to leave space for such a heading, or else simply responded to the opportunity shortly to begin a new section with the next, new column.

Do any other leaves from the manuscript have such elements? Might such a feature have existed in the exemplar from which this copy in humanist script was made?

The Span of Text on the Leaf

With its modern folio number 300, the text on the leaf starts and stops mid-phrase. It extends from within

[3340] Super Sent., lib. 1 d. 47 q. 1 a. 3 ad 1 ([Ad primum ergo dicendum] / voluntas enim . . . )

to within

[3340] Super Sent., lib. 1 d. 47 q. 1 a. 3 ad 1 ( . . . voliti cujus / [conditiones diversimode]

— via www.corpusthomisticum.org/snp1045.html.

Over time, the customary forms of citation for the different parts of the work have adapted to the demands and structure of Thomas’s complexly ordered texts. Guides in English for general readers can be found in the descriptions of How to Read an Article in Aquinas’s Summa Theologiae and Methods of referring to parts of the Summa theologiae. From the latter:

These parts [in the Summa] break down into questions (qq.); and each question (in Latin, quaestio, abbreviated q. or quaest.) is comprised of articles (etymologically, ‘little joints’ in the organic whole; a. = article). Most articles contain ‘objections’ (suggested arguments) on one side of an issue, an argument or quotation supporting the other side and introduced with the formula sed contra (‘on the other hand’), Thomas’ solution (solutio) in the body (corpus) of the article, and replies to the objections; replies open with the Latin preposition ad (‘to’ or ‘toward’) followed by an ordinal number (e.g., ad primum means ‘in reply to the first objection,’ while ad tertium indicates the reply to the third).

Expanding such citations, we might see that the text on the ‘new’ Leaf fits within the section of

Super Sententiis (“On the Sentences“), Liber (Book) 1, Distinctio (Part) 47, Quaestio (Question) 1.

Within that section, the leaf extends between its Articles 3 and 4, specifically from within this point:

Articulo (Article) 3, [Solutio] ad 1 (= primum) [Objectionum] = “Reply to the First Objection” within the body (corpus) of the Article [3340]

to within this point:

Articulo 4, s. c. [that is, Sed Contra = “On the contrary”, regarding] 1 [= primum Objectionum] [3349].

The Span of Text on Other Leaves

The spans of text on other leaves from the manuscript are indicated in some reference sources. They range from entries in sales catalogues to the metadata in catalogue entries online for individual collections.

The reported spans of text for some dispersed leaves are gathered into a single place. They are reported for the group of 15 participating institutions on the website ege.denison.edu for the cases of Leaf 40 within the FOL Portfolio in their particular sets, albeit with a few omissions because scans of some leaves or of the other side of some leaves were not available (“N/A”) when the website was being drawn up. On the site, identifications are reported for each leaf individually (accessible via Leaf 40), as well as gathered in the list of contents_31-40.php (at “Leaf 40”). Thus, with abbreviations for the names of the participating institutions (starting with Case for Case Western University):

Leaf 40: Aquinas’ Super Sententiis

Case: Lib. 1 d. 16 q. 1 a. 1 ad 5 [1235], to Lib. 1 d. 16 q. 1 a. 2 ad 1 [1250]

Cinci: Lib. 1 d. 11 q. 1 a. 1 ad 2 [897] , to Lib. 1 d. 11 q. 1 a. 2 ad arg. [912]

CIA: Lib. 1 d. 32 q. 1 a. 1 co. [2258], to Lib. 1 d. 32 q. 1 a. 2 arg. 2. [2292]

Clev: Lib. 1 d. 6 q. 1 a. 3 co. [532], to Lib. 1 d. 7 q. 1 a. 1 s. c. 1 [542]

Deni: Lib. 1 d. 33 q. 1 a. 2 arg. 5 [2357], to Lib. 1 d. 33 q. 1 a. 3 arg. 3 [2369]

Kent: Lib. 1 d. 32 q. 1 a. 3 arg. 1 [2303], to Lib. 1 d. 32 q. 2 a. 1 co. [2319] §

Keny: Lib. 1 d. 32 q. 2 a. 1 co. [2319], to Lib. 1 d. 32 q. 2 a. 2 qc. 1 co. [2331] §

Lima: Lib. 1 d. 3 q. 3 pr. [310], to Lib. 1 d. 3 q. 3 a. 1 ad 1 [318]

OSU: Lib. 1 d. 8 q. 5 a. 1 co. [749], to Lib. 1 d. 8 q. 5 a. 2 co. [758]

Oh U: N/A

Roch: Q. 1 a. 5 ad 4 [62], followed (!) by [Emphasis added] Q. 1 pr. [2]

U-Co: Lib. 1 d. 1 q. 4 a. 2 expos. [154], and Lib. 1 d. 2 q. 1 pr. [155]

U-Ma: Lib.1 d.4 q.2 a.2 expos. [452], to Lib.1 d.5 q.1 pr. [453]

U-Sk: N/A

U-SC: Lib. 1 d. 1 q. 3 a. 1 ad 4 [128], to Lib. 1 d. 1 q. 4 a. 2 s. c. 1 [149]

The system of identification accords with the version of the Commentary according to www.clericus.org, using the out-of-copyright edition of Sancti Thomae de Aquino, Scriptum super Sententiis (Parma, 1846).

Within that online edition, the series of arabic numerals (“[2]“, “[62]“, “[128]“, etc), offer convenient points of orientation and navigation within the complex text. Similarly, the modern folio numbers in pencil on some leaves (all?) permit ready recognition of where the individual leaves formerly stood in the manuscript itself.

Provisional List of Leaves

Because only some of the leaves are recognized, because only some of them have their span of text identified, because the folio numbers are visible on the images only of some of the rectos, and because more leaves await recognition and online display or access to view, I offer a provisional list of known leaves (and, where feasible, their textual span and/or folio number), according to the location of their current collection.

Reordering them into an original, or approximate, textual sequence would wait for a later stage of collective research. It is worth noting that the text on the leaves might not always run in the sequence presented or established in an edited version. This caution is shown by the span on the leaf now at the Rochester Institute of Technology (Set 35), as reported on the website ege.denison.edu, for Rochester Leaf 40.

“Q. 1 a. 5 ad 4 [62], followed (!) by Q. 1 pr. [2]”. (Emphasis added.)

Leaves According to Current Locations, Listed Alphabetically by Place-Name

Where known, the folio number on the leaf is indicated here in red (“Folio 12” etc) at the start of the entry.

I. Locations Unknown or Unspecified

*****

Private Collection, FBNC, Aquinas Leaf ‘Recto’. Reproduced by permission.

Folio 300. Location unspecified, Private Collection (unnumbered set of FBNC). Illustrated above and at the right.

[3340] Super Sent., lib. 1 d. 47 q. 1 a. 3 ad 1 ([ergo dicendum] / voluntas enim consequens), to

[3349] Super Sent., lib. 1 d. 47 q. 1 a. 4 s. c. 1 (voliti cujus / [conditiones diversimode])

— corpusthomisticum.org/snp1045.html.

*****

Folios ??. Location(s) unknown.

Group of 32 detached leaves from the manuscript offered for sale at the auction of Western Manuscripts and Miniatures at Sotheby’s, London, on 26 November 1985, as Lot 80 (with no plate). See below.

*****

Folio ?. Location unknown.

Leaf within FOL Set 55, offered for sale by Phillip J. Pirages, Catalogue 55 (n. d.), no. 111 (no plate).

*****

Folio ?. Location unknown.

Leaf within FBNC Set 28, offered for sale by Christie’s, 12 September 2020, lot. 10 unsold (no plate).

*****

II. Locations in Alphabetical Order

*****

Folio ?. Albany, NY, New York State Library (FOL Set 8).

*****

Folio ?. Amherst, MA, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, W. E. B. Du Bois Library (FOL Set 6).

Amherst Leaf 40 (verso) and via umass.edu (verso).

Verso only: [452] Super Sententiis, lib.1 d.4 q.2 a.2 expos., to [453] Super Sententiis, lib.1 d.5 q.1 pr.

— http://www.corpusthomisticum.org/snp1004.html. “A scan of the recto is not currently available”.

*****

Folio 66. Athens, OH, Ohio University, Vernon R. Alden Library (FOL Set 5). Manuscript leaf from Thomas Aquinas’ Commentary on the Sentences.

[764] Super Sent., lib. 1 d. 8 q. 5 a. 2 ad 6 ([non individuatur] / nisi ex corpore), to

[774] Super Sent., lib. 1 d. 8 q. 5 a. 3 ad 2(virtute secundum quod / [ex ejus essentia])

— via corpusthomisticum.org/snp1008.html.

*****

Folio ?. Bloomington, IN, Indiana University, The Lilly Library (FOL Set 2).

*****

Folio 14?. Boulder, CO, University of Colorado, Norlin Library (FOL Set 32). Boulder Leaf 40 (recto) and now here (recto and verso).

The online image of the recto appears to have no folio number.

“Super Primo Libro Sententiarum, fol. 14[?]v [sic]. Recto and verso: First Book of Sentences, 1.4.2.ex/68–2.1.pr/4″ (here).

[154] Super Sententiis, lib. 1 d. 1 q. 4 a. 2 expos., and

[155] Super Sententiis, lib. 1 d. 2 q. 1 pr.

— via corpusthomisticum.org/snp1001.html and corpusthomisticum.org/snp10020.html. (Boulder Leaf 40).

Buffalo and Erie Public Library, Ege, Otto F., compiler., “Fifty original leaves from medieval manuscripts.” (Leaf 40, verso). B&ECPL Digital Collections, accessed February 3, 2021, http://digital.buffalolib.org/document/1671.

http://digital.buffalolib.org/document/1671#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=44&z=0.349%2C0.1267%2C1.0344%2C0.6954.

*****

Folio 90. Buffalo, NY, Buffalo and Erie County Public Library, Central Library (Fol Set 11). Page ’70’, here.

[1046] Super Sent., lib. 1 d. 14 q. 2 a. 1 qc. 1 arg. 4 ([in operibus] / politicis sed), to

[1062] Super Sent., lib. 1 d. 14 q. 2 a. 2 arg. 4 (quod spiritus / [sanctus datus est])

— via corpusthomisticum.org/snp1009.html

*****

Folio ?. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University, Houghton Library (FOL Set 1, acquired at auction at Christie’s, London, on 6 December 2020, lot 9).

*****

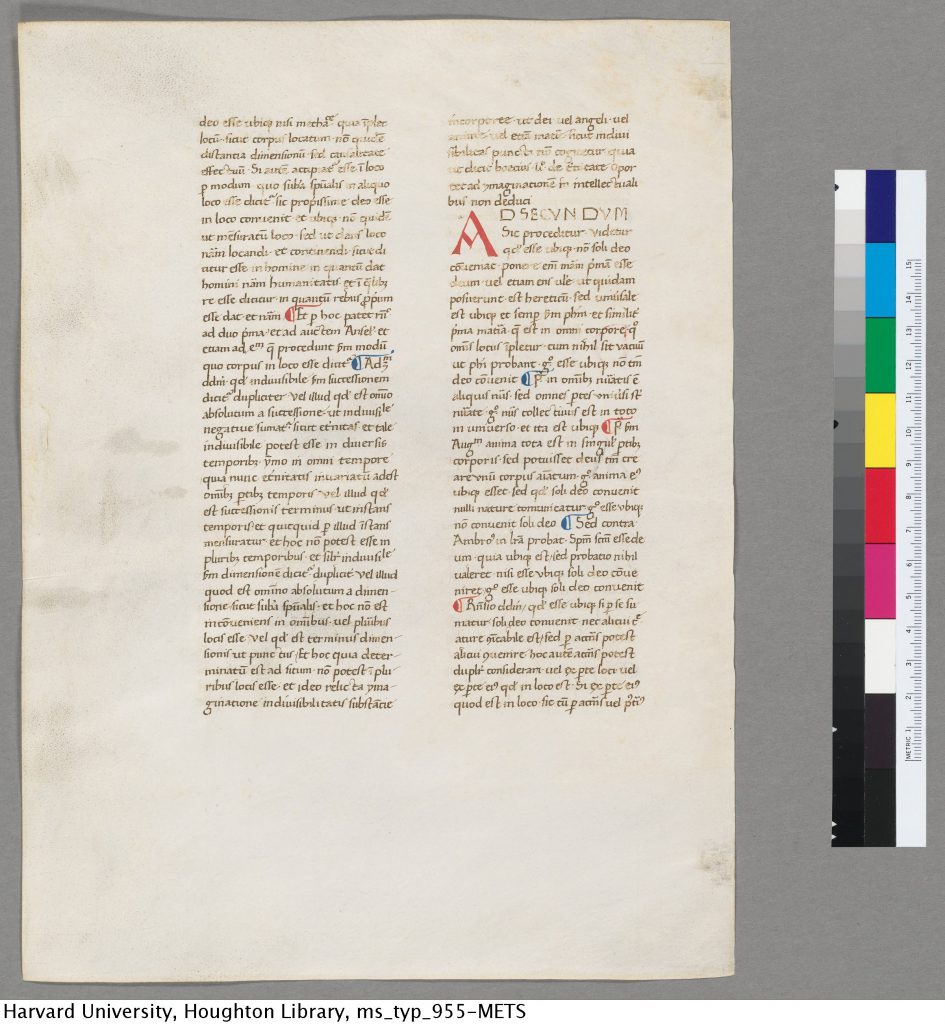

Folio 243. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University, Houghton Library, MS Typ 955.

“A single leaf containing the beginning of Distinctio 35, quaestio 1 ‘Quomodo Deus ubique esse dicitur’.”

[2626] Super Sent., lib. 1 d. 37 q. 1 a. 2 ad 3 ([ex parte ipsis dei] / operantis in rebus), to

[2645] Super Sent., lib. 1 d. 37 q. 2 a. 2 ad 1 (vel posterius / [conveniat toti quam])

— via corpusthomisticum.org/snp1035.html

In the last 2 lines on the verso, within the Response in Questio 2, Articulus 2, the scribe (or the exemplar) performed dittography by doubling the phrase ex arte eius quod in loco est.

Recto

Harvard University, Harvard University, Houghton Library, MS Typ 995, recto = Ege MS 40, folio 243 recto.

Verso

Ege MS 40, folio 243 verso. Harvard University, Houghton Library, MS Typ 955, verso.

*****

Folio 106. Cleveland, OH, Case Western University, Kelvin Smith Library (FOL Set 37). Case Leaf 40 and No. 40.

[1235] Super Sententiis, lib. 1 d. 16 q. 1 a. 1 ad 5, to

[1250] Super Sententiis, lib. 1 d. 16 q. 1 a. 2 ad 1

— corpusthomisticum.org/snp1009.html.

In Ege’s mat the original verso was turned to the front, because remnants of the gauze tape are visible on the original recto.

*****

Folio 78. Cincinnati, OH, Cincinnati & Hamilton County Public Library, Main Library (FOL Set 22). Cincinnati Leaf 40 and now here.

[897] Super Sententiis, lib. 1 d. 11 q. 1 a. 1 ad 2, to

[912] Super Sententiis, lib. 1 d. 11 q. 1 a. 2 ad arg.

— corpusthomisticum.org/snp1009.html” target=”_blank”>www.corpusthomisticum.org/snp1009.html.

*****

Folio ?. Cleveland, OH, Cleveland Institute of Art, Gund Library (FOL Set 4). CIA Leaf 40.

[2285] Super Sententiis, lib. 1 d. 32 q. 1 a. 1 co., to

[2292] Super Sententiis, lib. 1 d. 32 q. 1 a. 2 arg. 2.

– corpusthomisticum.org/snp1026.html.

*****

Folio ?. Cleveland, OH, Cleveland Public Library (Cleveland Leaf 40 )

[532] Super Sententiis, lib. 1 d. 6 q. 1 a. 3 co., to

[542] Super Sententiis, lib. 1 d. 7 q. 1 a. 1 s. c. 1

— corpusthomisticum.org/snp1004.html.

*****

Folio 12. Columbia, SC, University of South Carolina, Rare Books and Special Collections (RBSC), Otto F. Ege Collection, No. 40 (FOL Set 27).

USC Leaf 40 and No. 40.

[128] Super Sententiis, lib. 1 d. 1 q. 3 a. 1 ad 4, to

[149] Super Sententiis, lib. 1 d. 1 q. 4 a. 2 s. c. 1

— corpusthomisticum.org/snp1001.html.

According to USC Leaf 40: “Reconstruction Note! In Ege’s original manuscript, this leaf was probably followed by what is now Leaf 40 in the University of Colorado, Boulder portfolio.” See above and further below.

*****

Folio ?. Columbus, OH, The Ohio State University, Thompson Library (FOL Set 2). OSU Leaf 40.

[749] Super Sententiis, lib. 1 d. 8 q. 5 a. 1 co., to

[758] Super Sententiis, lib. 1 d. 8 q. 5 a. 2 co.

— www.corpusthomisticum.org/snp1008.html.

*****

Folio ?. Gambier, OH, Kenyon College, Olin Library (FOL Se 23). Kenyon Leaf 40.

[2319] Super Sententiis, lib. 1 d. 32 q. 2 a. 1 co., to

[2331] Super Sententiis, lib. 1 d. 32 q. 2 a. 2 qc. 1 co.

— http://www.corpusthomisticum.org/snp1026.html.

As noted by Kenyon Leaf 40: “Reconstruction Note! In Ege’s original manuscript, this leaf followed what is now Leaf 40 in the Kent State University portfolio.” See below.

*****

Folio 219. Granville, OH, Denison University, William Howard Doane Library (FOL Set 30). Denison Leaf 40

[2357] Super Sententiis, lib. 1 d. 33 q. 1 a. 2 arg. 5, to

[2369] Super Sententiis, lib. 1 d. 33 q. 1 a. 3 arg. 3

— .corpusthomisticum.org/snp1033.html.

*****

Folio 207. Greensboro, NC, University of North Carolina, Jackson Library (FOL Set 38). Page 040.

*****

Folio ?. Hartford, CN, Wadsworth Athenaeum (FOL Set 10).

*****

Folio ?. Kent, OH, Kent State University Libraries (FOL Set 15). Kent Leaf 40.

The online image of the recto does not extend to the upper corner for a folio number.

[2303] Super Sententiis, lib. 1 d. 32 q. 1 a. 3 arg. 1, to

[2319] Super Sententiis, lib. 1 d. 32 q. 2 a. 1 co. [2319]

— www.corpusthomisticum.org/snp1026.php.

According to Kent Leaf 40 : “Reconstruction Note! In Ege’s original manuscript, this leaf was followed by what is now Leaf 40 in the Kenyon College portfolio.” See below.

*****

Folio ?. Lima, OH, Lima Public Library, Main Library (FOL Set 29). Lima Leaf 40.

[310] Super Sententiis, lib. 1 d. 3 q. 3 pr., to

[318] Super Sententiis, lib. 1 d. 3 q. 3 a. 1 ad 1

— corpusthomisticum.org/snp1003.html.

*****

Folio 70. Minneapolis, MN, University of Minnesota (FOL Set 13). Ege Manuscript 40 and Ege Manuscript 40 recto.

University of Minnesota Libraries, Ege Manuscript 40, Recto. Image via Creative Commons.

*****

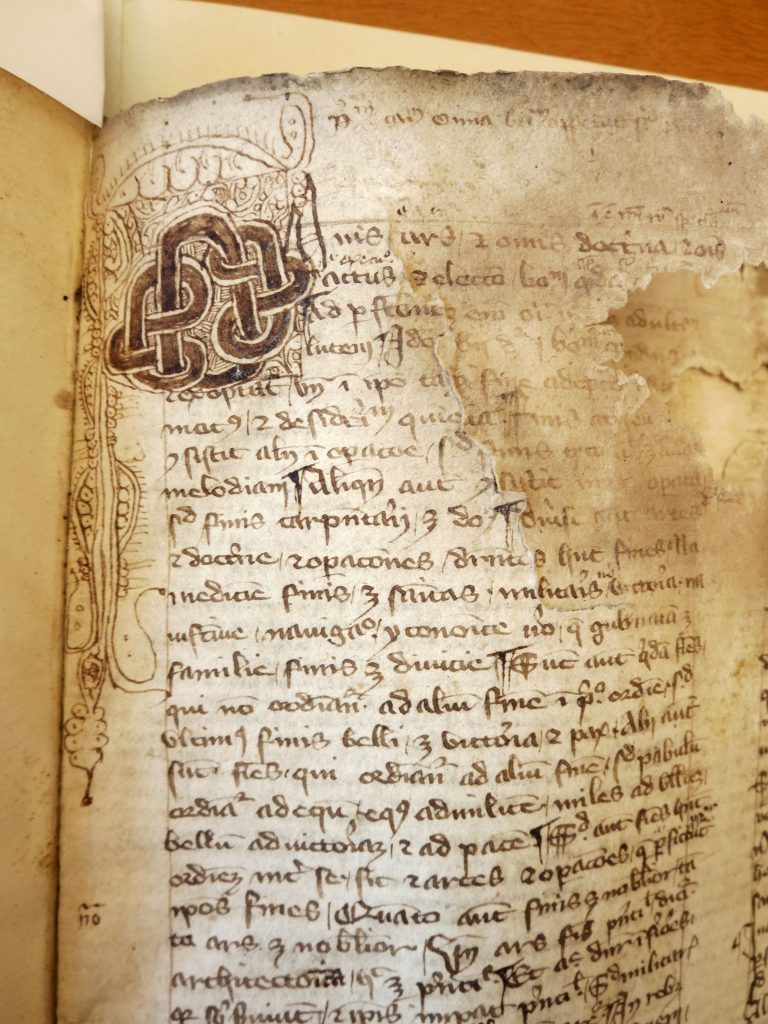

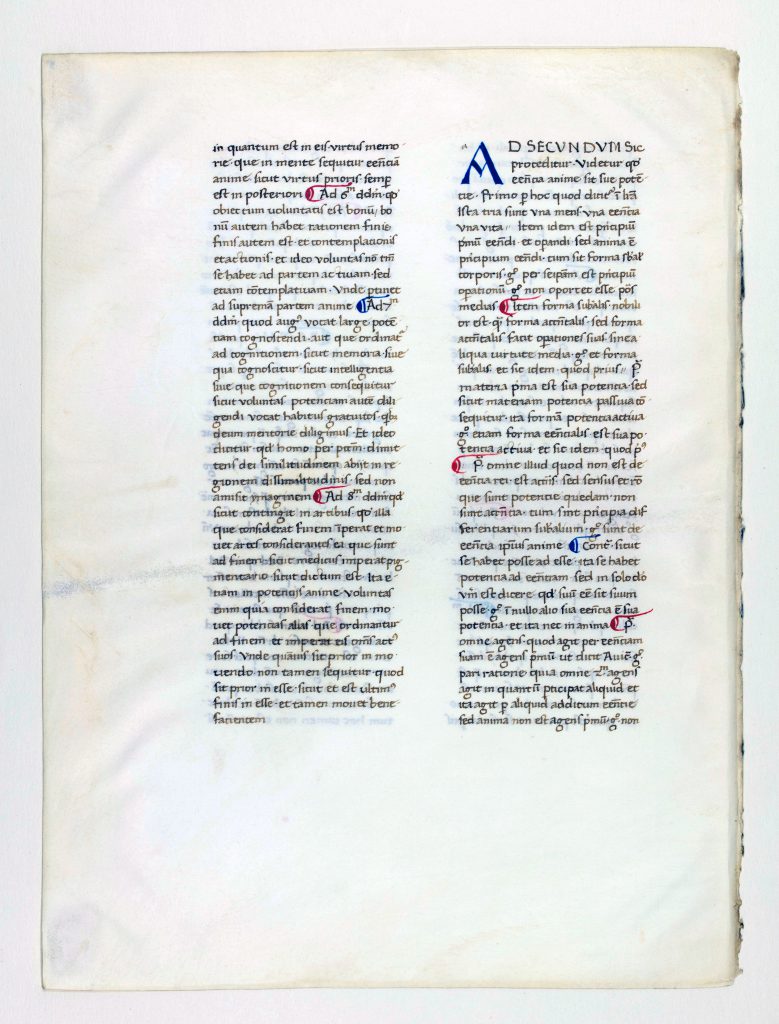

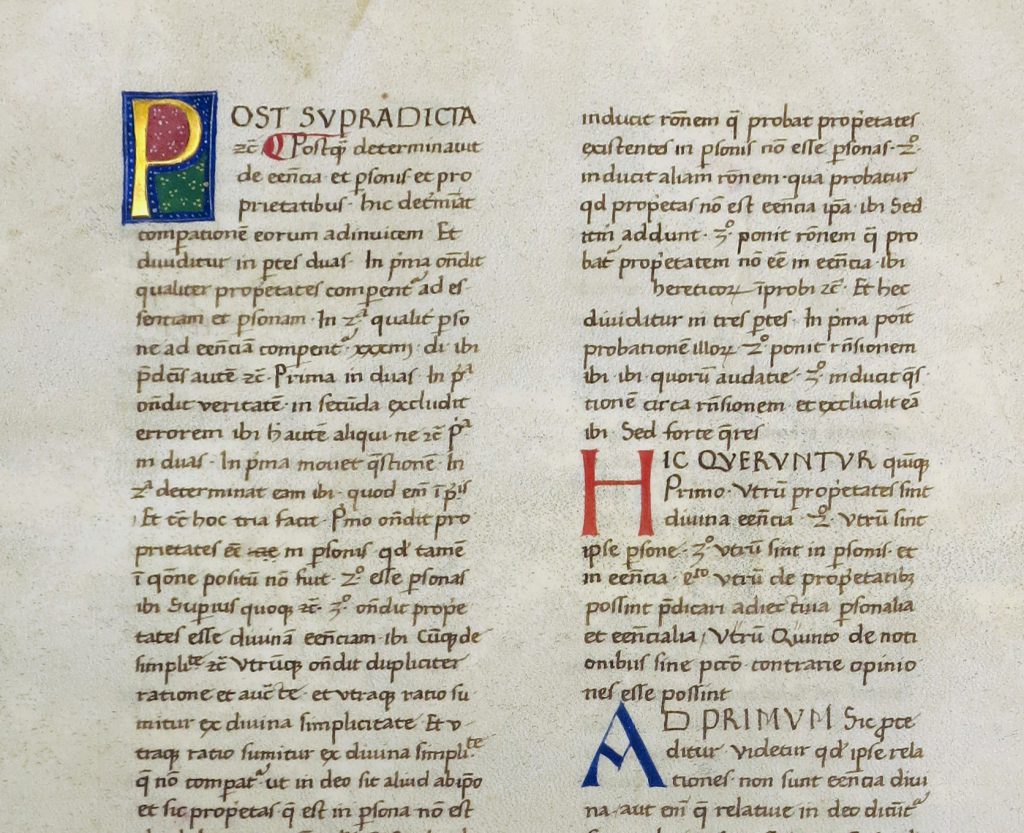

2 Folios. New Haven, CT, Yale University, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection (FOL Set 3, the “Ege Family Portfolio”).

In this Specimen, there are 2 separate (and non-consecutive) Leaves within the Mat, one after the other.

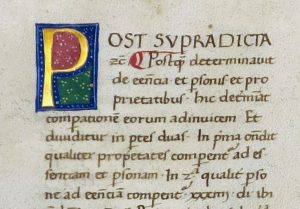

Folio ‘1’. Opening leaf of the Text, with a full-page frame on the recto.

[1] Super Sent., pr. (up to Ipse dedit quosdam / [apostolos quidam])

Folio 216. The leaf is turned back-to-front as it is hinged to the mat.

[2331] Super Sent., lib. 1 d. 32 q. 2 a. 2 qc. 1 co. ([etiam sapientia] / genita dicitur), to

[2341] Super Sent., lib. 1 d. 33 q. 1 a. 1 arg. 2 (essentia divina / [est paternitas])

— via corpusthomisticum.org/snp1026.html and corpusthomisticum.org/snp1027.html

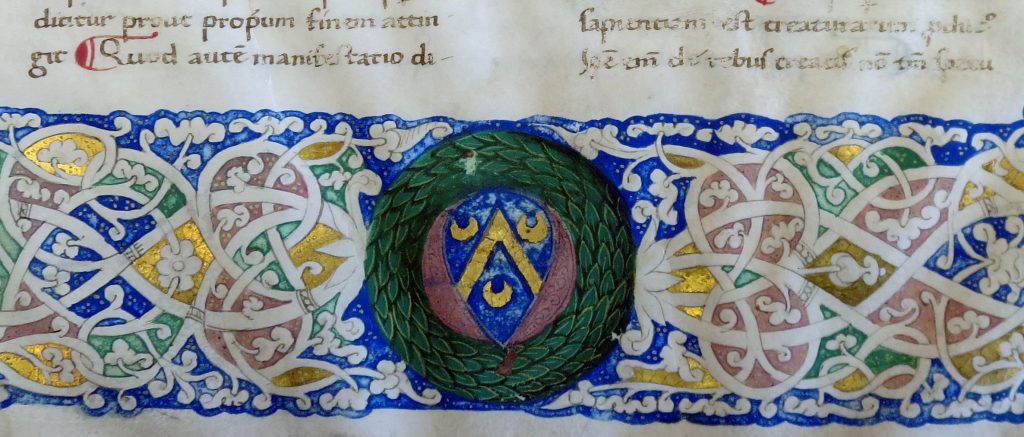

The illuminated initial P (for Post) at the top of the verso opens Distinctio 33.

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, MS 40, Specimen 2 = folio 216v (turned to the front in Ege’s Mount: Top Left. Photography Mildred Budny.

*****

Folio ?. New York, NY, Morgan Library (FOL Set 28).

*****

Folio ?. Newark, NJ, The Newark Public Library, Special Collections Department, Medieval Manuscript Collections (FOL Set 34). 40. Thomas.

The online images for the leaf crop the pages, so that the folio number (if there is one) is out of frame.

The initial D for Deinde in column b on the recto opens Liber I, Distinctio I, Quaestio 3, Articulus 1.

= [118] Super Sent., lib. 1 d. 1 q. 3 a. 1 arg. 1 via corpusthomisticum.org/snp1001.html

*****

Folio ?. Northampton, MA, Smith College, Neilson Library, Mortimer Rare Book Room (FOL set, unnumbered).

*****

Folio 188. Princeton, NJ, Princeton University, Firestone Library (FBNC Set 20).

The span: [nomine verba] / et filius non distinguuntur . . . nullo modo / [praecedit intellectu]

[2011] Super Sent., lib. 1 d. 27 q. 1 a. 1 ad 4 + [2014] Super Sent., lib. 1 d. 27 q. 1 a. 2 arg. 1, to

[2024] Super Sent., lib. 1 d. 27 q. 1 a. 2 ad 4

[The text skips [2012] Super Sent., lib. 1 d. 27 q. 1 a. 1 ad 5.]

The initial A (for Ad) in column a on the recto opens Distinctio 27, Article 2.

*****

Folio 6. Rochester, NY, Rochester Institute of Technology, Wallace Center (FOL Set 35). Rochester Leaf 40 and now online via the RIT Libraries website: Record Number b1426520 (for the Commentary leaf), but linked incorrectly to images (here) actually for a different manuscript Specimen — recte Ege MS 39 (Livy, in its folio 39) — while the images of Ege MS 40 are wrongly identified as Ege MS 41 (Gregory the Great et al.).

“Aquinas’s Super Sententiis, q. 1 a. 5 ad 4 [62], followed (!) by Super Sententiis, q. 1 pr. [2], the latter of which begins at the illuminated ‘H'”

— via corpusthomisticum.org/snp0001.php. “A scan of the recto is not currently available.”

Now available (here, despite the mislabelling), the scan shows that the recto begins within [58] Super Sent., q. 1 a. 5 co.

[Note: The full set of Leaves in this FOL Set is displayed online, but some images and identifications are interchanged.]

*****

Folio 50. Saskatchewan, SK, University of Saskatchewan, Murray Library (FOL Set 25). University of Saskatchewan (recto only, and with no ID of the text), and also David Brindle et al., 50 Medieval Manuscript Leaves: The Otto Ege Collection at the University of Saskatchewan Library (2011), pp. 174–177 (recto and verso)

[565] Super Sent., lib. 1 d. 7 q. 1 a. 3 co., to

[593] Super Sent., lib. 1 d. 7 q. 2 a. 2 qc. 1 ad 2

— via corpusthomisticum.org/snp1004.html

*****

Folio 135. Seattle, WA, University of Washington, University Libraries, UW MS 83 (recto only). (See also below.)

Recto: “Book I, Distinction 19, Questions 2 and 3. (UW MS 83 recto)”

“Incipit and Explicit: //motus in illo sicut in propria mensura . . . potentia contra magnitudinem//”

Recto only:

[1504] Super Sent., lib. 1 d. 19 q. 2 a. 2 ad 1 ([nunc temporis] / motis in illo . . . ),

to [1513] Super Sent., lib. 1 d. 19 q. 3 a. 1 arg. 4 ( . . . potentia contra magnitudinem / [Ergo non intelligitur])

– via corpusthomisticum.org/snp1019.html

*****

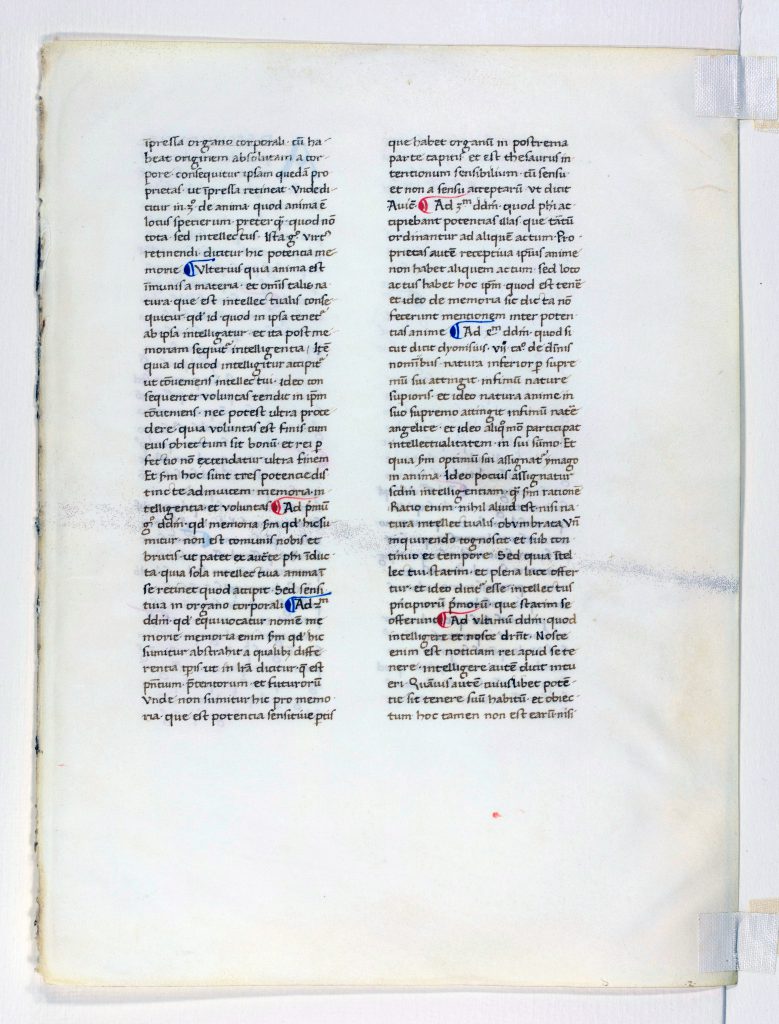

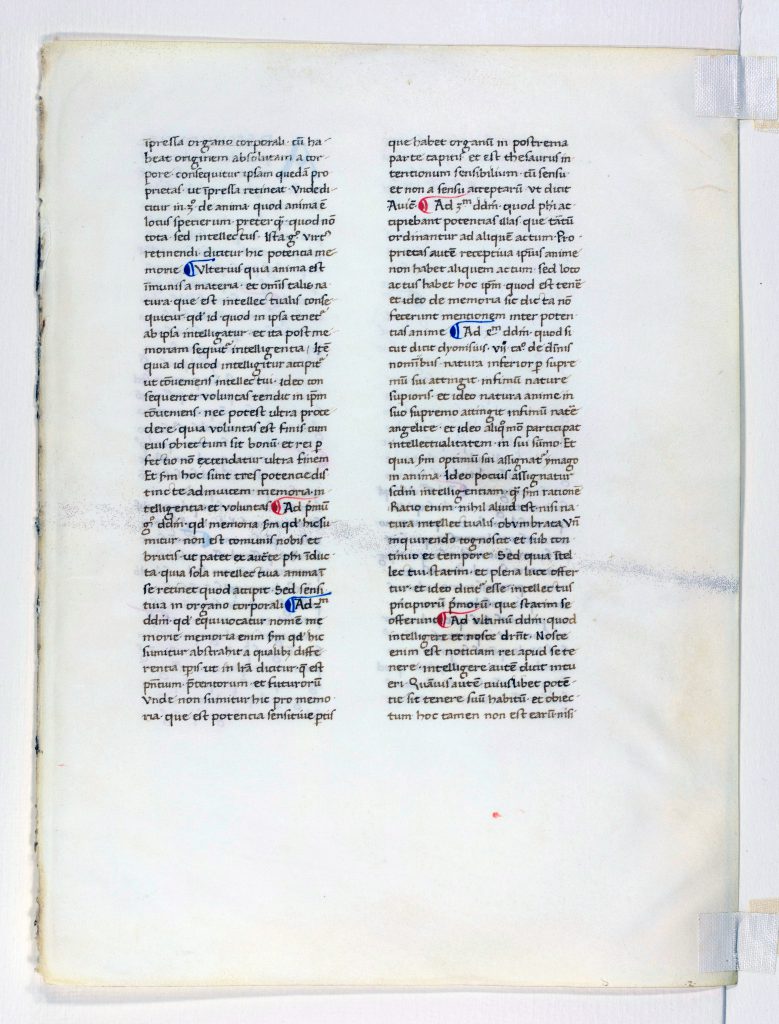

Folio ?. Stony Brook, NY, Stony Brook University Libraries, Special Collections and University Archives (FOL Set 19). Thomas Aquinas: Commentary.

The folio number is covered by one of Ege’s gauze mounting tapes.

[333] Super Sent., lib. 1 d. 3 q. 4 a. 1 co. ([et non sit] / impressa organa corporali), to

[349] Super Sent., lib. 1 d. 3 q. 4 a. 2 s. c. 2 (Ergo non / [est agens])

— via corpusthomisticum.org/snp1003.html

Original Recto

Otto F. Ege: Fifty Original Leaves from Medieval Manuscripts, Leaf 40, “Verso”, Special Collections and University Archives, Stony Brook University Libraries.

Original Verso

Otto F. Ege: Fifty Original Leaves from Medieval Manuscripts, Leaf 40, “Recto”, Special Collections and University Archives, Stony Brook University Libraries.

*****

Folio 75(?). Toledo, OH, Toledo Museum of Art, 1953.129A–XX (FOL Set 12), 1953.1929NN. Manuscript leaf from the Commentary on the Sentences, No. 40.

Ege’s mounting turned the recto to the back side.

[863] Super Sent., lib. 1 d. 10 q. 1 a. 4 co. ([dicimus duos homines] / amantes se et concordes esse), to

[874] Super Sent., lib. 1 d. 10 q. 1 a. 5 co. (determinetur per specialem / [modum originis])

— via corpusthomisticum.org/snp1009.html.

*****

Folio ?. Toronto, ON, Art Gallery Ontario (FOL Set 16).

*****

Folio ?. Toronto, ON, Ontario College of Art and Design (OCAD), Dorothy H. Hoover Library (FOL Set 36).

*****

Folio ?. Toronto, ON, University of Toronto, Massey College, Robertson Davies Library, Gurney FF 0001 (FOL Set 17).

*****

Etc.

*****

A Note about Consecutive Leaves

A few leaves among the identified survivors can be seen to have been consecutive in the original manuscript.

Two cases are signaled in the website ege.denison.edu (see above), on the basis of spans of text. Cases of this kind may be confirmed by consecutive folio numbers (where known or discoverable) and by the consecutive course of the text.

1) Evidently adjacent

[Folio ?]. Kent [State University]: Lib. 1 d. 32 q. 1 a. 3 arg. 1 [2303], to Lib. 1 d. 32 q. 2 a. 1 co. [2319] §

( . . . concedendum est quod / [genita sapiens sit])

>

[Folio ?]. Keny[on College]: Lib. 1 d. 32 q. 2 a. 1 co. [2319], to Lib. 1 d. 32 q. 2 a. 2 qc. 1 co. [2331] §

([concedendum est quod] / genita sapiens sit . . . )

— ending on the verso of the one and beginning consecutively on the recto of the other (. . . concendum est quod / genita sapiens sit . . . )

2) Evidently not

[Folio 12]. U-S[outh]C[arolina]: Lib. 1 d. 1 q. 3 a. 1 ad 4 [128], to Lib. 1 d. 1 q. 4 a. 2 s. c. 1 [149] ( . . . quia caritas nunquam / [excidit sed proximus])

? > × [Instead, a leaf or more went in between them, with text spanning excidit sed proximus . . . in speculo cogniscimus, or the like]

[Folio 14?]. U-Co[lorado at Boulder]: Lib. 1 d. 1 q. 4 a. 2 expos. [154], and Lib. 1 d. 2 q. 1 pr. [155] ([in speculo cogniscimus] / excidit sed proximus . . . )

Near Rather than Adjacent

Like that ‘not-quite consecutive’ pair of leaves now in South Carolina and Colorado, some leaves formerly stood near each other, rather than adjacent. For example:

Folio 66 (Ohio University) and

Folio 70 (University of Minnesota)

Folio 216 (Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library) and

Folio 219 (Denison University).

A Note about Descriptions and Metadata

Library catalogues and descriptions of separate leaves from the manuscript, as part of Ege’s Portfolios or from other sources, mostly employ the Labels which Ege composed to accompany them, just like that. Often the metadata for the Leaves quote those Labels, in whole or in part. Sometimes, an identification of the span of text is proferred, as with Leaf 40 at Boulder at the University of Colorado, and MS Typ 955 at the Houghton Library.

An exemplary case is offered by the description for Folio 135, catalogued as Seattle, WA, University of Washington, University Libraries, UW MS 83 (with image of the recto only). See also above.

Besides identifying the location of the text (as an “excerpt”) within Aquinas’s Commentary (“Book I, Distinction 19, Questions 2 and 3” on the recto), and citing the first and last words on the leaf (the Incipit and Explicit), the description mentions specific features of script, ruling, layout, and condition. It results from direct observation of the object itself (or of the image of its recto), thereby noting and reporting some salient bibliographical and related characteristics specific to the leaf and to its manuscript context.

Text in brown ink. Initials 13 mm (3 lines) high at the start of Question 3 and Article 1.

Guide letter visible to the left of the large red A.

Other arguments and counter-arguments are set off by a colored paragraph mark, in alternating blue and red.

Layout: Two columns, 37 lines each. Drypoint ruling, ruling lines redrawn on verso with leadpoint.

Script: Use of Arabic numerals; Clearly-spaced letters and words; Upright d; Few abbreviations; Strokes over i; Feet on the minims; Continued use of e for ae so likely an early example of humanist. When several i’s are in a row, the last one is elongated. Double-bowl g and tall s at the end of words.

Condition: Excellent condition overall, some lines faint (probably water damage). Hair follicles visible.

Contextual Remarks. The Scriptum Super Sententiis is one of Thomas Aquinas’s earliest writings. In this excerpt from his commentary on Peter Lombard’s Sentences, he considers the three persons of the trinity, and the definition of eternity.

*****

Specimens

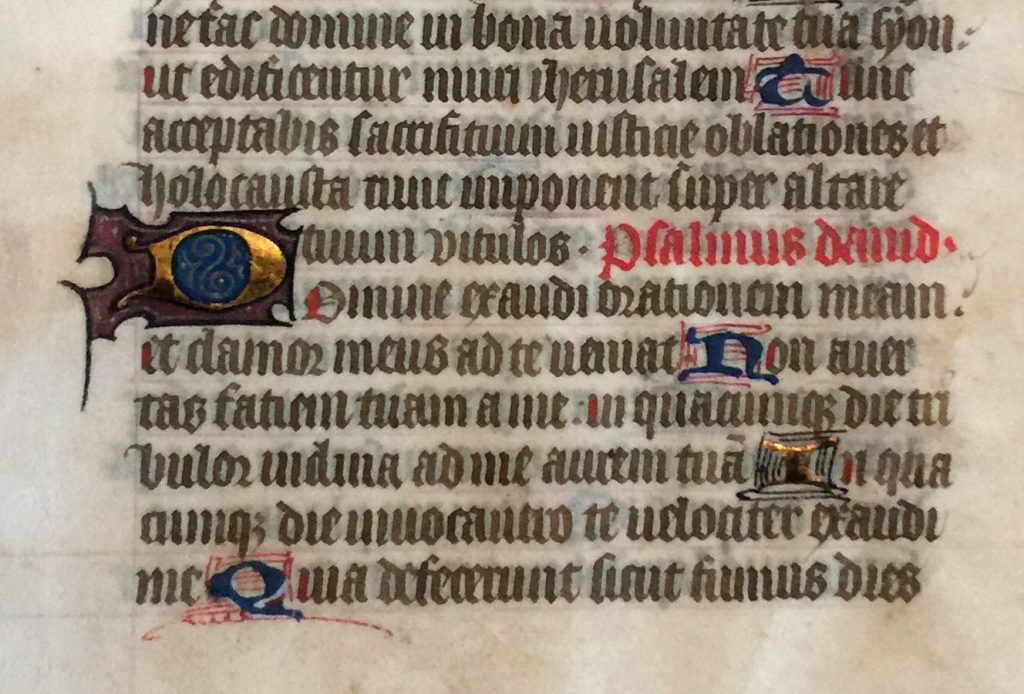

Some Specimens present the text similarly to the ‘New’ Leaf, as they present an enlarged 3-line initial (red or blue) for a significant section, followed by a line or part-line of capital letters in ink. Paragraph-markers, alternately in red and blue, signal subdivisions of text within the sections.

Leaf 40 in FOL Set 19 (Stony Brook University) offers such a case. On the verso, Column b (or ‘vb’) begins with the inset 3-line initial A (for AD) in blue pigment, with a cue-letter a to one side.

Otto F. Ege: Fifty Original Leaves from Medieval Manuscripts, Leaf 40, “Recto”, Special Collections and University Archives, Stony Brook University Libraries.

Other parts of the text receive more elevated grades of embellishment. Usually they take the form of taller inset 4-line initials placed within rectangular frames and provided with polychrome pigment, including gold, as well as simple geometric decoration. Examples include the P (for Post) at the top of column a on Folio 216v. As Ege positioned this Leaf, he turned the verso forward, facing front, and leaving the customary, less embellished, text on the original recto to press against the back board of the mat.

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, MS 40, Specimen 2 = folio 216v (turned to the front in Ege’s Mount. Photography Mildred Budny.

Note that, unlike the various editions of Aquinas’s Commentary on the Sentences of Peter Lombard, this manuscript has — insofar as the revealed pages and leaves indicate — no numbering system or running titles by which to navigate a course through it. Nor, apparently, does it provide names for the different parts (Distinctio, Articulus, etc.).

To say that the presentation of this copy may constitute a challenge to consultation of the lengthy and complexly structured text perhaps is an understatement. It may be significant that the leaves which have surfaced from the manuscript do not carry marks of consultation in the forms of corrections, annotations, readers’ marks, and the like — aside from the modern folio-numeration in pencil and the marks of ownership.

*****

Continuing to examine this manuscript, Part II in our series (II of III) now turns to

As customary with Ege’s dismembered manuscripts, Sales Catalogues can offer significant (and tantalizing) information, both before and after Ege altered and distributed them.

*****

Before moving to the next Post, we make sure to thank the owner of the ‘new’ Portfolio and the owners of other specimens for permission to examine them and for permission to reproduce the images. Thanks, as always, for the advice, encouragement, and suggestions of colleagues, students, and friends!

Do you know of other leaves from this Aquinas manuscript? Other Sets of the Portfolio of Famous Books in Nine Centuries (FBNC), or Sets of the Fifty Original Leaves (FOL)? Do you recognize the work of the scribe(s) in other manuscripts?

Please let us know. Please leave your Comments here, Contact Us, and/or visit our Facebook Page. We look forward to hearing from you.

Private Collection, FBNC, Aquinas Leaf ‘Front’ top right. Reproduced by permission.

*****