Specimens of Ege Manuscript 40 in the Ege Family Portfolio

March 19, 2021 in Manuscript Studies, Uncategorized

Specimens of the Aquinas Manuscript in Humanist Script

(Ege Manuscript 40)

in the ‘Ege Family Portfolio’

— Part III of III in the series on this manuscript —

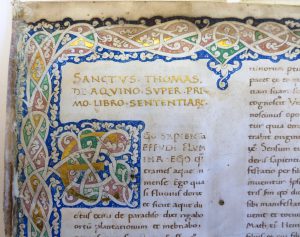

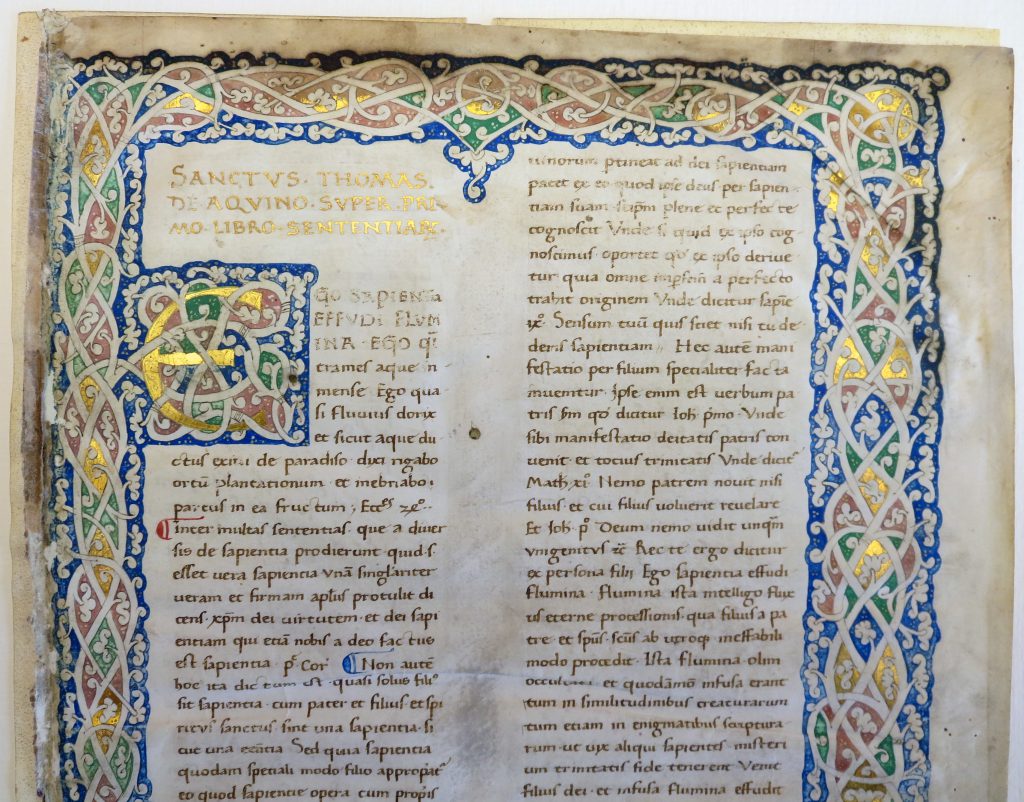

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, MS 40, Specimen 1: folio ‘1’r, Bottom Center. Photography Mildred Budny.

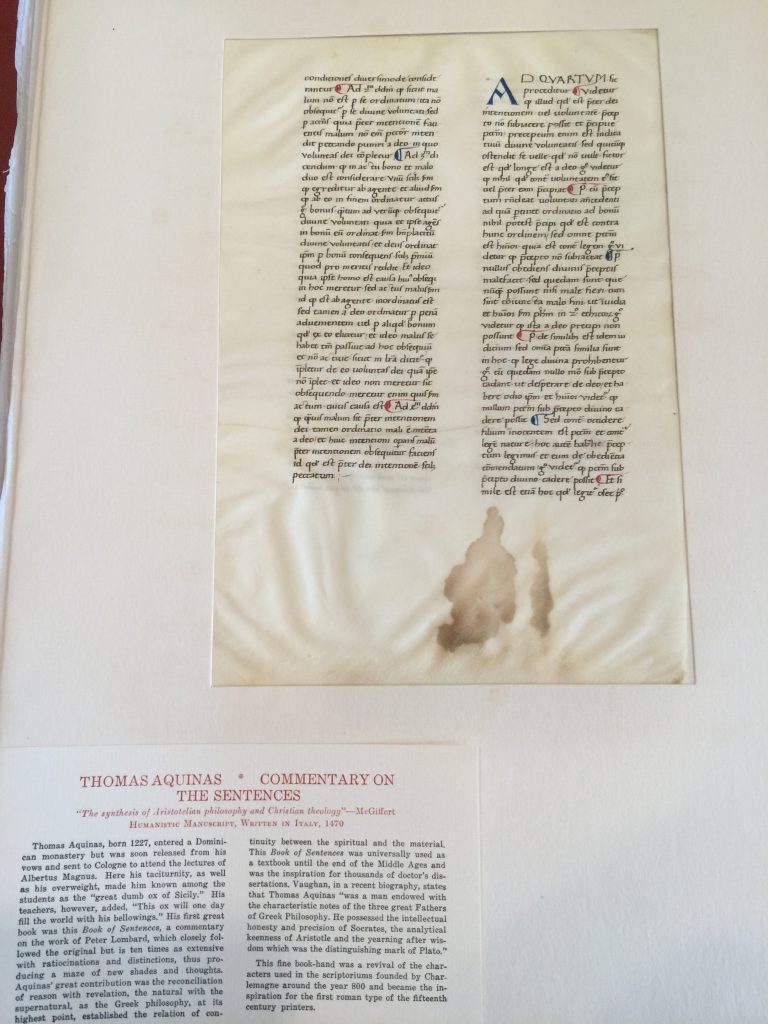

Thomas Aquinas, Commentary on Book I of Peter Lombard’s Sentences

Written in Latin on vellum

Italy, probably late 15th Century (circa 1475)

Circa 288 × 210 mm <Written area circa 178 × 130 mm>

Double columns of 37 lines

in Humanist Script (with Gothic Features)

*****

Folios ‘1’ and 216

[1] Super Sententiis, Prooemium (to Ipse dedit quosdam)

and

[2331] Super Sent., Liber 1, Distinctio 32, Quaestio 2, Articulo 2 (qc. 1 co), to [2341] Distinctio 33, Quaestio 1, Articulo 1 (arg. 2)

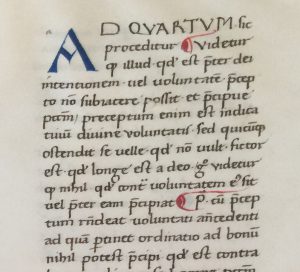

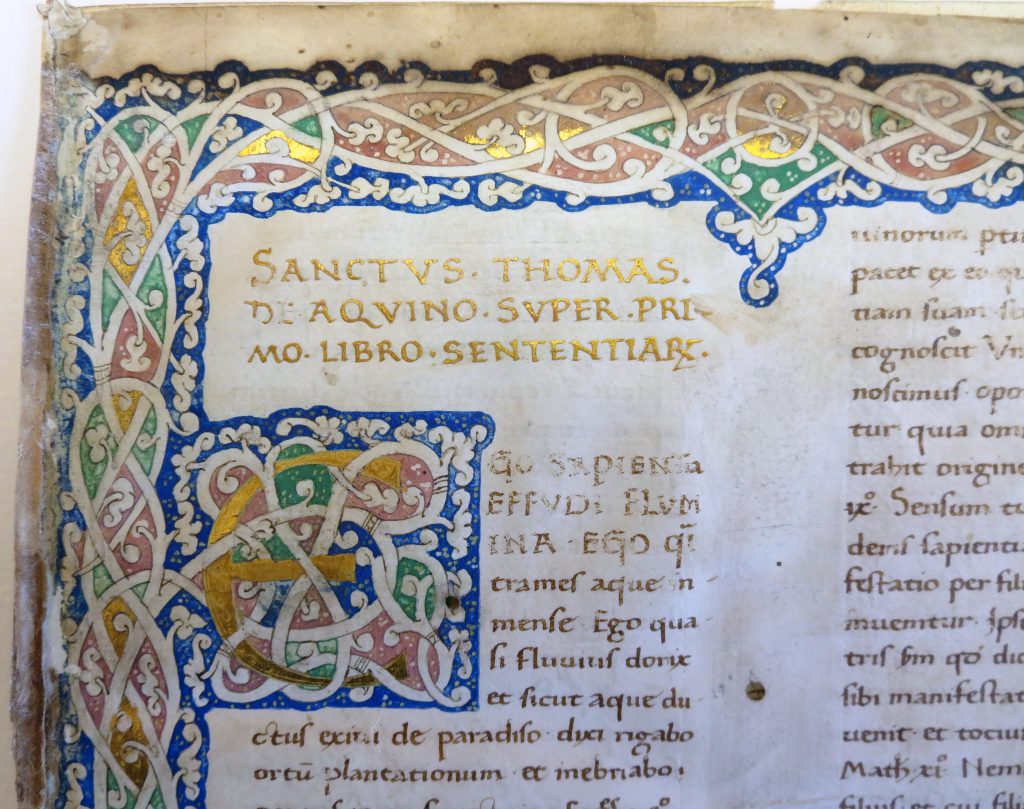

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, MS 40, Specimen 2 = Folio 216v, Top Left. Photography Mildred Budny.

Previously, in exploring the Portfolio of Famous Books assembled by Otto F. Ege, we examined the 15th-century Aquinas Manuscript whose dismembered specimens appear in 2 of his Portfolios. See

- Part I: Otto Ege’s “Aquinas Manuscript in Humanist Script” (Ege Manuscript 40).

- Otto Ege Manuscript 40, Part II: Before and After Ege

Now we reach Part III of III.

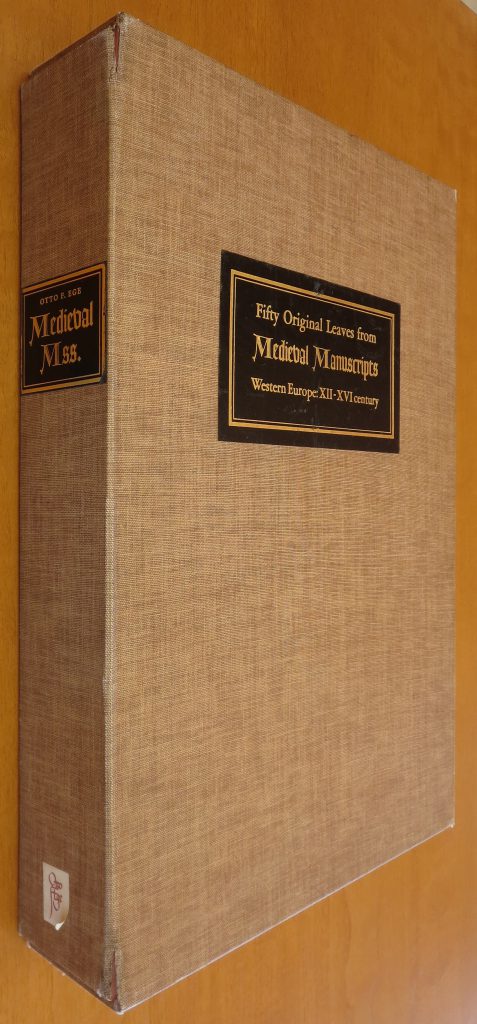

Known as Ege Manuscript 40 from its assigned number in the Portfolio of Fifty Original Leaves from Medieval Western Manuscripts (“FOL”), its leaves also joined Ege’s Portfolio of Famous Books in Nine Centuries (“FBNC”) as the 6th Manuscript Specimen (of 6). By virtue of its FOL position, it appears in the Handlist of Otto Ege’s Manuscripts (2016), as no. 40 (pp. 131–132 etc.).

Humanist Script and Book-Production

Its case pertains to the notable genre of Humanist Manuscripts, which emerged in Italy from the early 15th century onwards. Illustrated descriptions of the origins and development of Humanist(ic) Script include:

- Humanistic Script, via Digitized Medieval Manuscripts, and

- Humanist Minuscule, via Wikipedia.

Displays of such books include:

- The Humanistic Book at The Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge.

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, MS 40, Specimen 1: folio ‘1’r, Top Left. Photography Mildred Budny.

There, we find a concise description of the phenonemon (I emphasize several elements in red).

In Italy in the early fifteenth century a revolution took place in the script and decoration of the manuscript book, first in Florence, and very soon after in the rest of the peninsula. It involved the rediscovery of classical texts, the revival of ancient literature as a central element of the curriculum, the reform of Latin spelling, and a new style of writing, called by its contemporaries littera antica and known to us today as ‘humanistic script’.

The new type of book received a new style of decoration. At first, it was limited to the white-vine scrolls meandering around birds, butterflies, and chubby little boys, the ubiquitous putti. But by the mid-fifteenth century, illuminators were experimenting with three-dimensional images corresponding to the antiquarian passions of Humanist scholars and collectors. Ancient inscriptions, jewels, and archaeological finds inspired the illusionistic monumental frontispieces and architectural title pages, one of the most lasting contributions of the Humanistic manuscript to book design.

As they come into view, more leaves from the fragmented Ege Manuscript 40 allow its case to assume its proper place within the robust tradition of Humanist script and book-production. Now we focus upon the special contributions which its leaves in the ‘Ege Family Portfolio’ can make to a fuller understanding of its origin and history.

Ege’s Portfolios

Private Collection, Ege’s FBNC Portfolio, Aquinas Leaf, Recto, Top Right. Reproduced by Permission.

Some of our blogposts have considered these different Portfolios assembled by Ege, as shown in our Contents List. Recent posts examine the FBNC Portfolio as presented in a newly revealed set in a Private Collection. Each focuses upon one of the manuscript specimens, which occupy position [1] and [6] respectively in the Portfolio (that is, first and last in the group of its 6 specimens from manuscripts).

- Otto Ege’s Portfolio of Famous Books and ‘Ege Manuscript 53’ (Koran/Quran)

- Otto Ege’s “Aquinas Manuscript in Humanist Script” (Ege Manuscript 40).

Previously, on the track of an isolated leaf in a Private Collection, we examined another manuscript whose specimens circulated in the FBNC Portfolio. It is Ege’s 14th-century “Aristotle Manuscript from Erfurt” (Ege Manuscript 51), for which unfolding research after the first post yielded more discoveries, reported in a follow-up post.

- More Leaves from ‘Otto Ege Manuscript 51’ (Aristotle’s Nichomachean Ethics Etc.)

- Volume II and More Parts of ‘Otto Ege Manuscript 51’

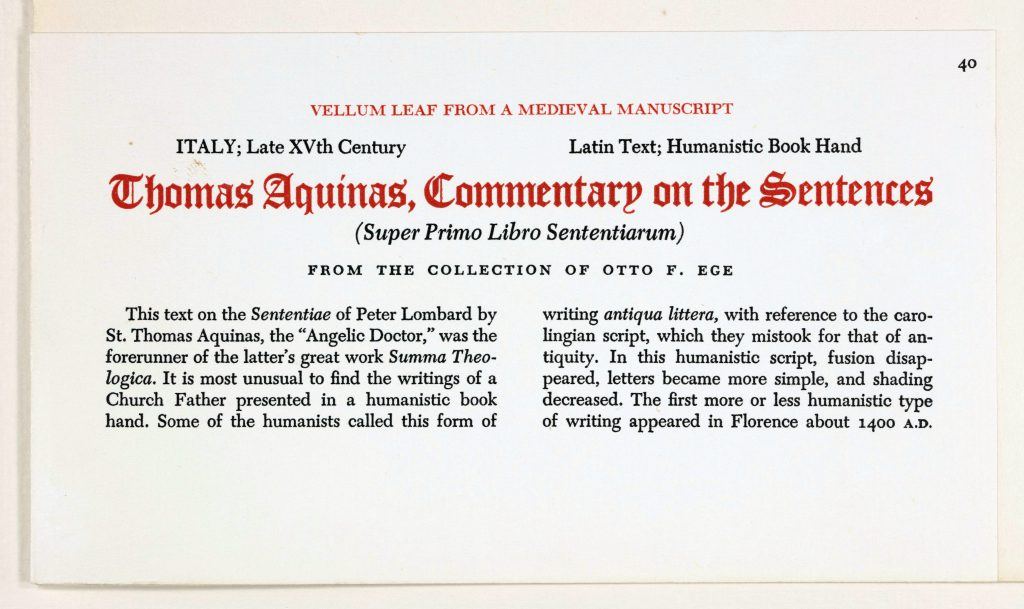

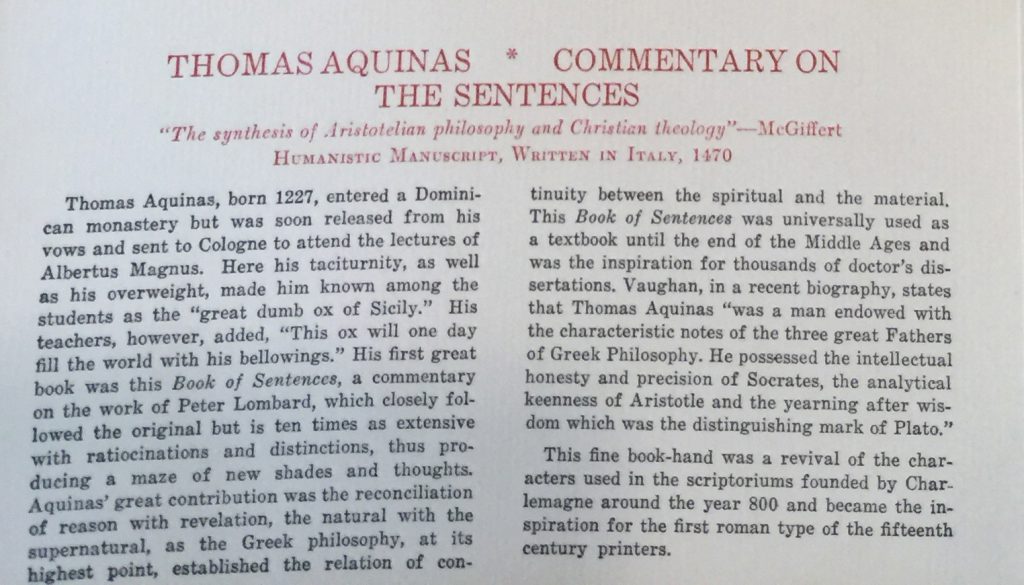

Now we examine more parts of the Aquinas manuscript. To it, Ege assigned dates of ‘1470’ or ‘Late XVth Century’ in different contexts, as he distributed it as specimens variously

- in FOL as its numbered Leaf 40,

- in FBNC as its unnumbered Leaf [6],

- and separately, with or without framed mats.

In particular, we look more closely at 2 of its Specimen Leaves which stand as a pair for Leaf 40 in Set Number 3 of the FOL Portfolio, the “Ege Family Portfolio”. They contain significant evidence of the former character, decoration, and ownership of the manuscript.

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, Side View of Case. Photography Mildred Budny.

The “Ege Family Portfolio”

Numbered Label for the Family Album (Set Number 3) of Otto Ege’s Portfolio of ‘Fifty Original Leaves’ (FOL). Otto Ege Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. Photograph by Mildred Budny.

As part of the “Otto Ege Collection” now at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Set 3 of FOL is regarded as the “Ege Family FOL Portfolio”. In various ways, the Set seems to be special, as it contains exemplary leaves from its manuscript sources, kept in reserve for the family collection. Some features are illustrated in our 2016 Symposium Program Booklet. The ‘special’ items among the specimens in this Portfolio include these instances:

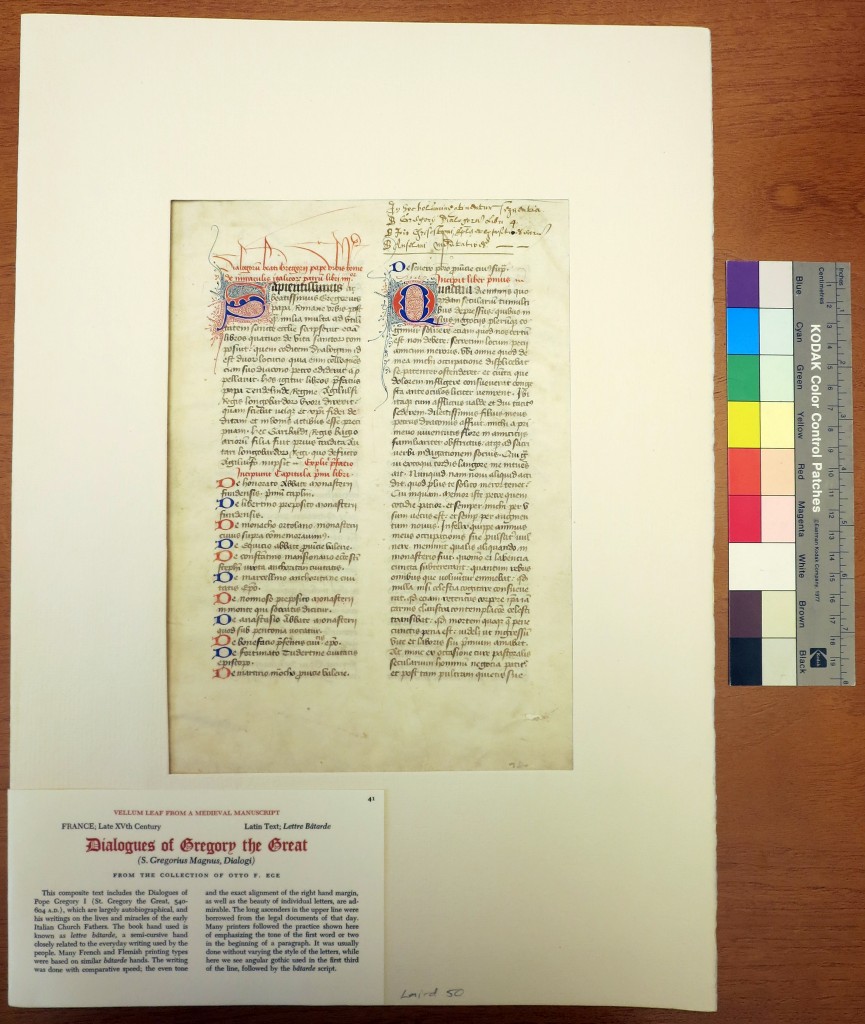

1) Ege Manuscript 41

Its specimen for Leaf number 41 presents the opening leaf of the late 15th-century Latin manuscript. The manuscript offers a copy from Flanders of texts by various authors, beginning with the Dialogues of Gregory the Great. Focusing upon Gregory and his text, Ege’s Label ignores the others. Brief descriptions of the manuscript while it was still intact mention other texts, but leave uncertain their sequence and full range.

The specimen in Set 3 of FOL provides clearer evidence of the medieval sequence, without the full set of leaves to tell their story themselves. In an added entry written in the upper margin, the recto of the first leaf holds the medieval contents list for the texts. That survival holds significance for assessing the former extent and sequence of the manuscript, for which Ege presented only a partial, restricted view. Our blogposts examine the unfolding evidence:

- More Discoveries for Otto Ege Manuscript 41 (after the emergence of the medieval contents-list into view).

Leaf 41 within its Mat with Printed Label in the Family Album (Set Number 3) of Otto Ege’s Portfolio of ‘Fifty Original Leaves’ (FOL). Otto Ege Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. Photography Mildred Budny.

2) Ege Manuscript 31

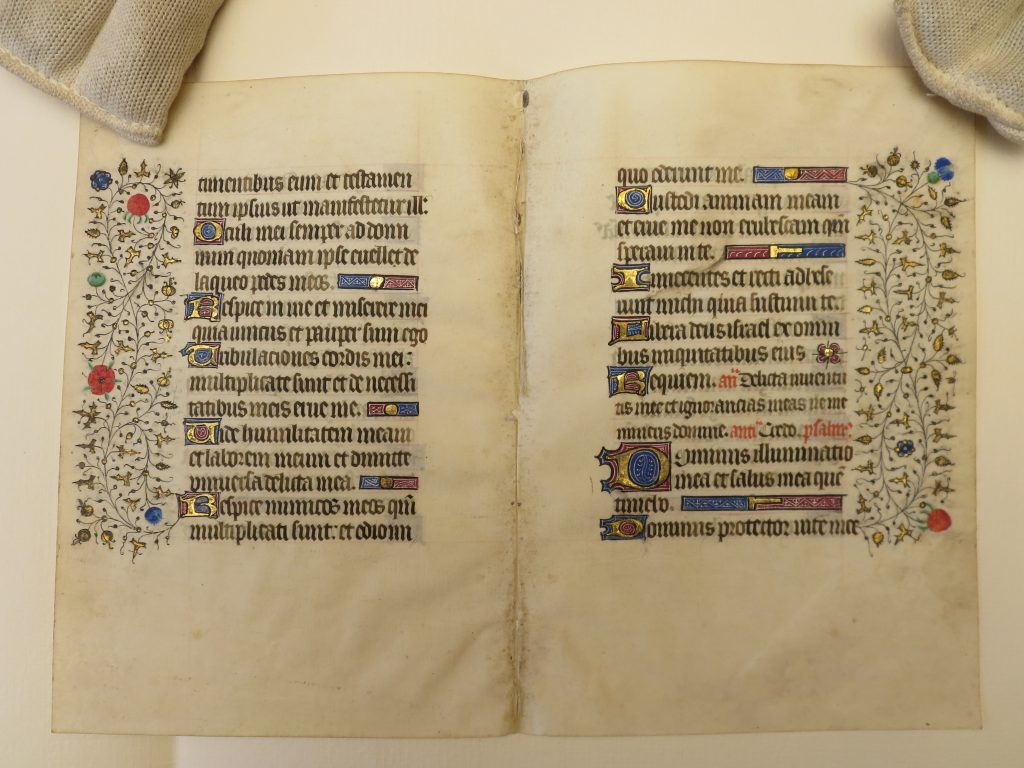

Sometimes in Ege’s Portfolios, the framed mat for a specific manuscript contains more than 1 leaf from it. Neither the Contents List of the Portfolio and the Label for the Specimen Manuscript prepare us for the unusual ‘bonus’. It does not emerge into view until the windowed front of the hinged double-boarded mat is turned to open its frame and to inspect the Specimen Leaf itself. Next, turning that first Leaf to see its back reveals a fellow Leaf ‘hiding’ behind it.

The cases which I have seen of this ‘bonus’ in Ege’s Portfolios or singly-framed Specimens mainly comprise a bifolium rather than a single leaf. That is, the Specimen retains the other side, or leaf, in the folded pair of leaves which belonged to a single sheet of animal skin. For such cases, a single set of Ege’s gauze hinging tapes (2 or 3 tapes along one side customarily serves the purpose of fastening the specimen(s) into place.

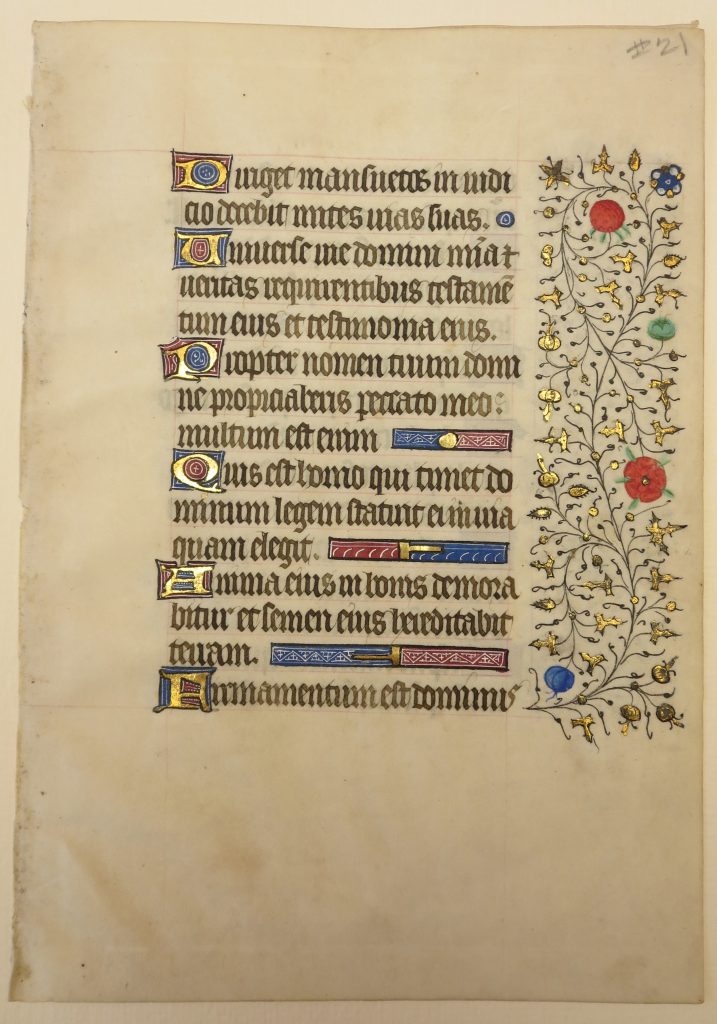

The bifolium for Specimen 31 in the Ege Family Portfolio is such a case. It comes from a Book of Hours made in France (probably Paris), circa 1425–1450, as notes in the Handlist of Otto Ege’s Manuscripts (2016), no. 31 (page 128). Normally the Portfolios display 1 leaf as their specimen (as here). This one carries its ‘bonus’.

The Front (First Recto)

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, Ege Family Portfolio, ‘Leaf 31’, First recto of Bifolium. Photography Mildred Budny.

The Opened Bifolium: First Verso facing Second Recto

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, ‘Leaf’ 31, Bifolium opened. Photography Mildred Budny.

The Back (Second Verso)

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, ‘Leaf’ 31, Bifolium Back. Photography Mildred Budny.

The text on the bifolium runs consecutively from its first leaf to its second, showing that it lay in the manuscript as a unit on its own or at the center of a quire, nested within other folded bifolia and/or single leaves. This portion contains the text of Psalms, from verse 19 of Psalm 24 (or 23 by alternate reckoning) to the end of that Psalm, and from the opening of Psalm 27 (26), which begins Dominus illuminatio mea (“The Lord is my Light”), to partway through its verse 4.

Note that not always do the ‘bonus’ bifolia in Ege’s frames carry text in consecutive leaves. The gaps between their texts demonstrate that their former manuscripts placed one or more leaves between them. Identifying the course, or disrupted course, of the text on these leaves indicates which position the ‘bonus’ bifolia used to hold in their books, because their framed forms, as presented by Ege, do not carry any notes to that effect.

3) Ege Manuscript 40

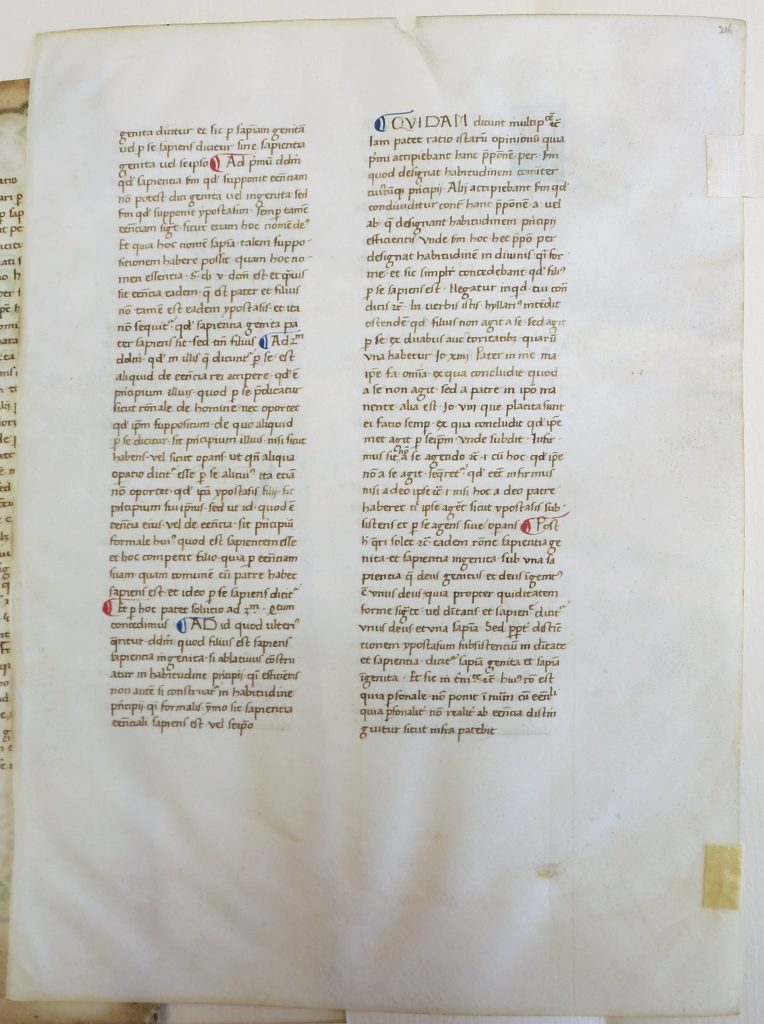

Unlike such bifolia, the ‘bonus’ in the doubled specimens for the Aquinas manuscript in the Ege Family Portfolio represents 2 separate leaves. Moreover, they came from far distant parts of the manuscript. Let us turn their pages and have a look.

The Aquinas Specimens: Two Leaves in One Mat

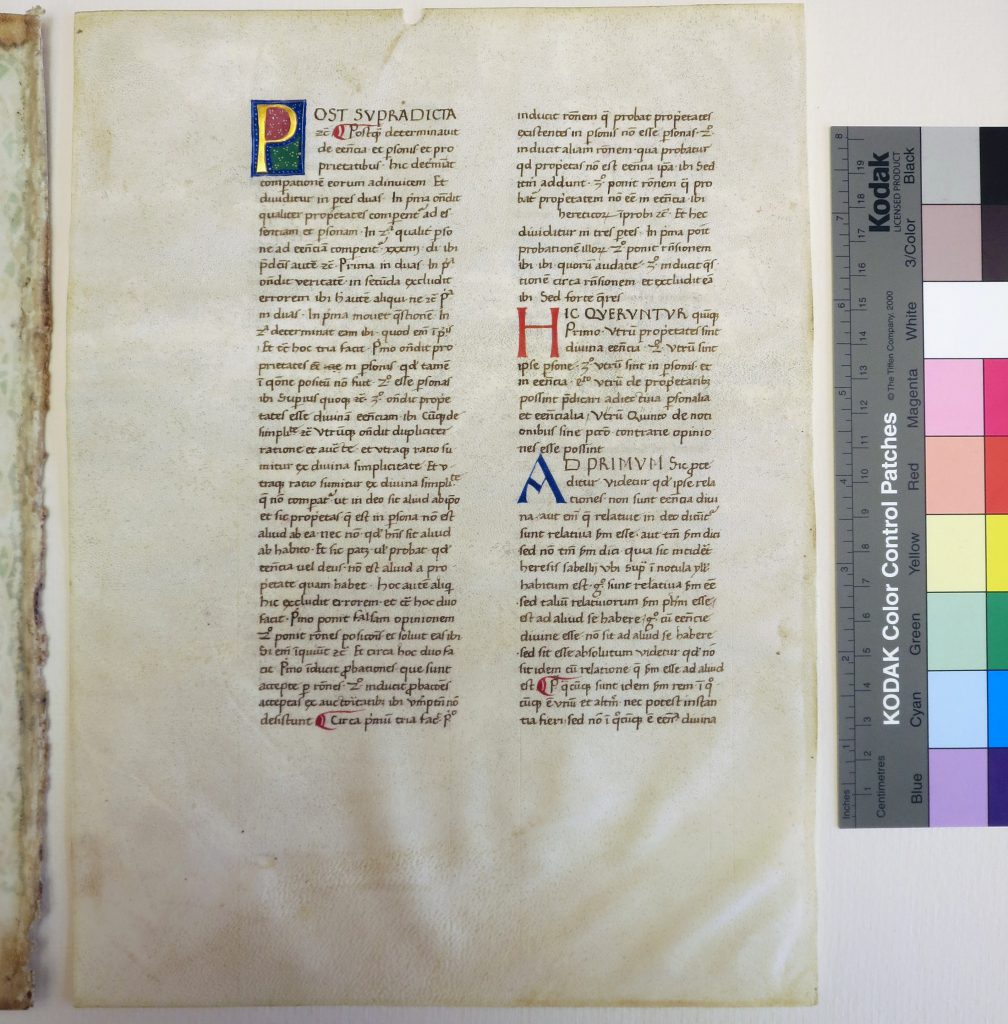

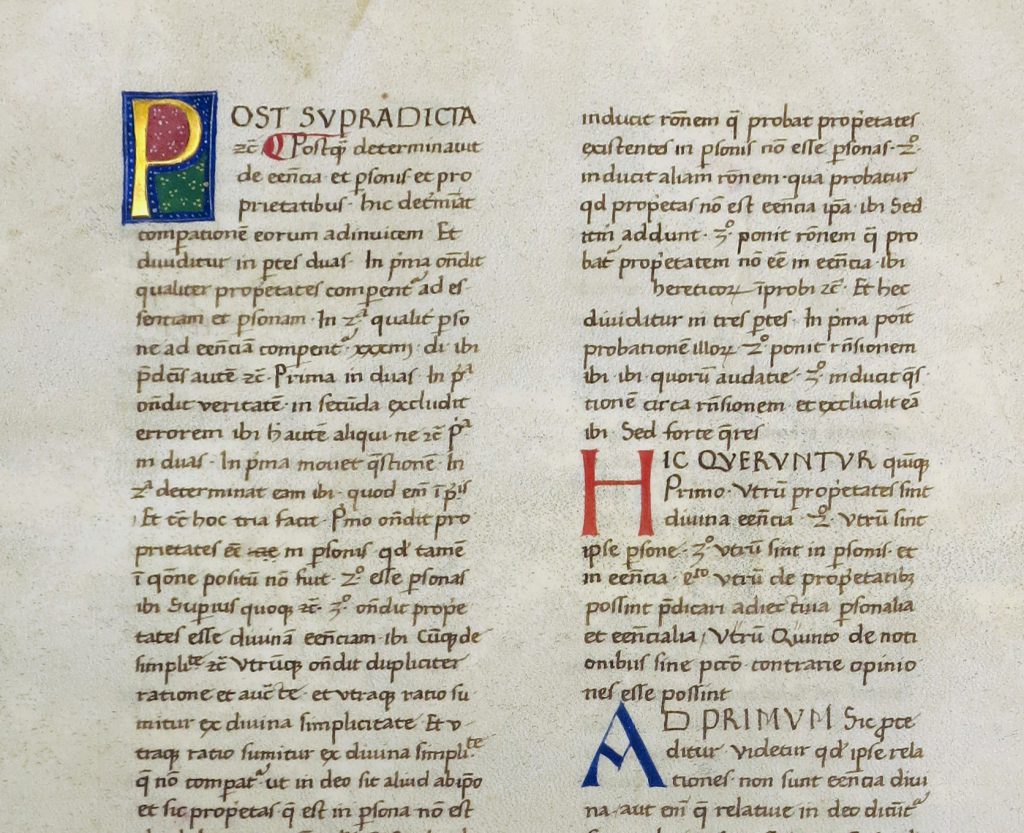

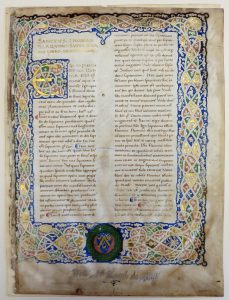

In this set of FOL, the closed frame for Leaf 40 shows 1 leaf, as customary for the framed specimens. The view through the window onto the first leaf shows a partly cropped and offset decorative framework enclosing the text-block of double columns.

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, MS 40, Specimen 1 in Mat with Ege’s Label. Photography Mildred Budny.

In other sets of FOL, the standard leaf from the manuscript, without a decorative framework, stands more neatly and sedately within the window in Ege’s framed mat, leaving viewing room to spare in the margins around the text block. (See Otto Ege’s “Aquinas Manuscript in Humanist Script” .) In the ‘new’ FBNC in a Private Collection, it appears thus:

Private Collection, FBNC Aquinas Leaf in Mat with Label. Reproduced by permission.

In the ‘Ege Family Portfolio’, Set 3 of FOL, behind that first leaf stands another leaf.

A ‘Bonus’ Leaf as Added Insertion

The matted frame encloses 2 separate, non-consecutive, Leaves, one after the other. Turning the first to its verso reveals the second. The second one, as mounted, is already turned to the verso, with its original recto pressed against the back board of the mat. The second leaf obviously came from a different, distant, part of the book. That distance is demonstrated by, among other things, the distinctly different condition of the 2 leaves.

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, MS 40, Specimens 1 and 2, with folios ‘1’v and 216v. Photography Mildred Budny.

The dramatically different conditions of the 2 leaves tells a poignant tale. The relatively clean condition of the one contrasts with the signs of significant damage on the other, which suffered from exposure to moisture and other elements, especially at the edges. It seems obvious that Ege took care to salvage that leaf, despite its poor showing, on account of its major decoration, which lifts the book into an august realm of manuscript production.

The framed mat was evidently prepared at first with a single specimen leaf, representing a more-or-less standard leaf of the text. Such leaves have moderate or modest enhancement for the opening of a section — an enlarged initial in colored pigment, followed Capital letters for the rest of the line — and with colored Paraph marks (Pilcrows) for subsections within the running text. Many leaves from the manuscript exhibit such features, although not all pages include an enhanced section opening.

Next (sooner or later), apparently as an afterthought or change in plan, the second leaf was inserted into the frame, in front of the other leaf. The elaborately decorated leaf now faces front in the frame, assuming once more a forward or forefront position, as it had manifestly occupied in the original manuscript, with its title and opening for the work overall.

Specimens 1 and 2

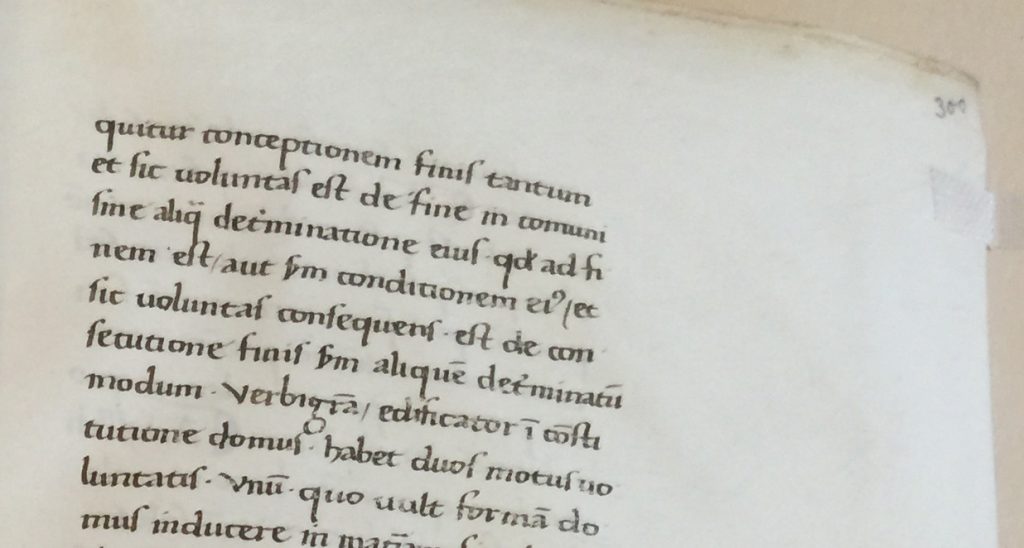

Let us call this pair of leaves for Leaf 40 in this Set Specimen 1 and Specimen 2. At least one of them carries a folio number, pertaining to the same series of arabic numerals entered in pencil in the top corners as other leaves. The series runs high, as seen already on folio 300, in a Private Collection:

Private Collection, FBNC, Aquinas Leaf ‘Back’ top right and page number. Reproduced by permission.

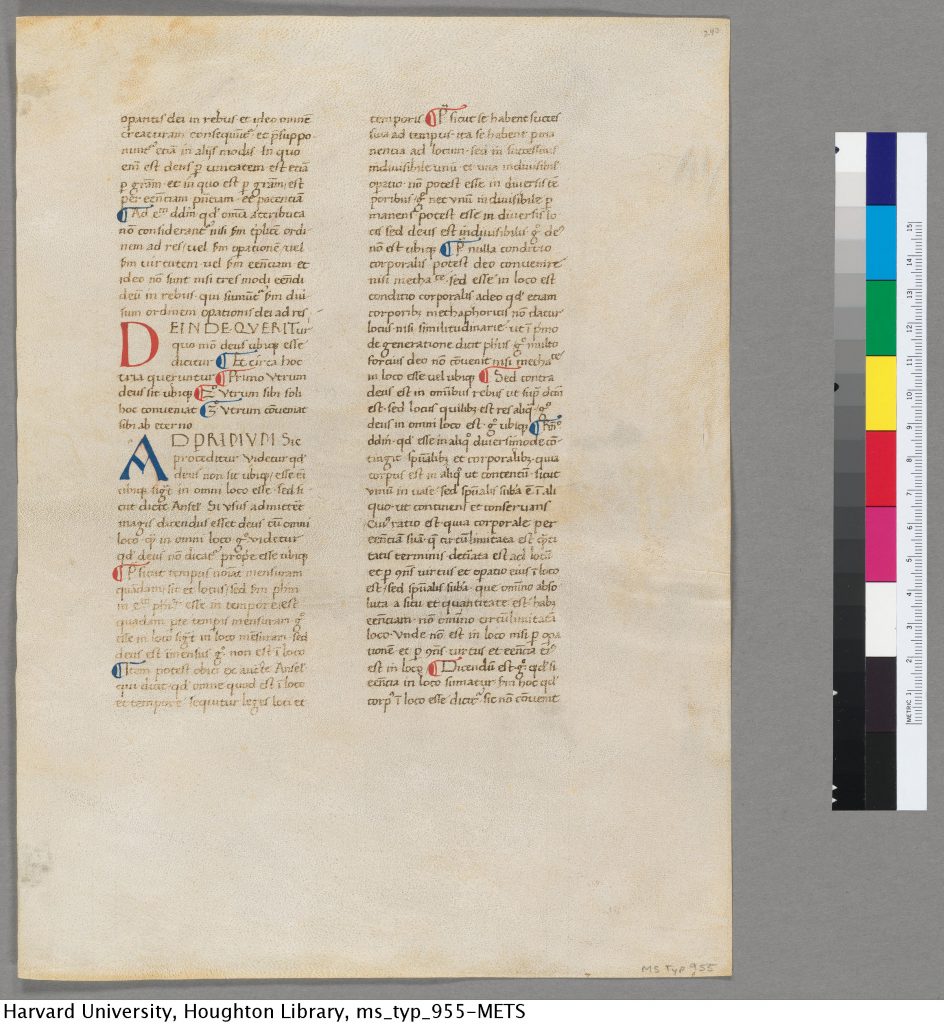

Specimen 2 carries the number 216 on one side (or page).

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, MS 40, Specimen 2 = folio 216r, top left. Photography Mildred Budny.

This side, which formerly served as recto, is the ‘plainer’ side of the leaf. It lacks an enhanced section opening, unlike the original verso. As often in his preparation of framed specimens for Portfolios and other forms of distribution, Ege’s positioning turned that verso to the front, so as to showcase, and to display, the seemingly more ‘interesting’ page. The original recto has Ege’s gauze hinging tapes, which indicate the intention for this specimen to occupy the frame in a first iteration.

A next step inserted the other, more prominent, leaf in front of Specimen 2. It, too, places the ‘plainer’ side toward the back, but, in this case, that plainer side also corresponds to the original verso. Specimen 1 might have a folio number on its recto, but it is not clear whether it does, at least from my photographs and any of my notes on site.

The Spans of Text

In keeping with a standardized method of identifying the locations of parts of Thomas’s complex arguments in his Commentary on the Sentences of Peter Lombard (see Otto Ege’s “Aquinas Manuscript in Humanist Script” ), the spans on the 2 leaves belong to these portions:

Folio ‘1’. Opening leaf of the Text, with a full-page ‘rectangular’ foliate frame on the recto. The span of text:

[1] Super Sent., pr. = Prooemium (“Prologue” or “Preface” to the work), up to Ipse dedit quosdam / [apostolos quidam . . . ]

— as in the edition via http://www.corpusthomisticum.org/snp0000.html

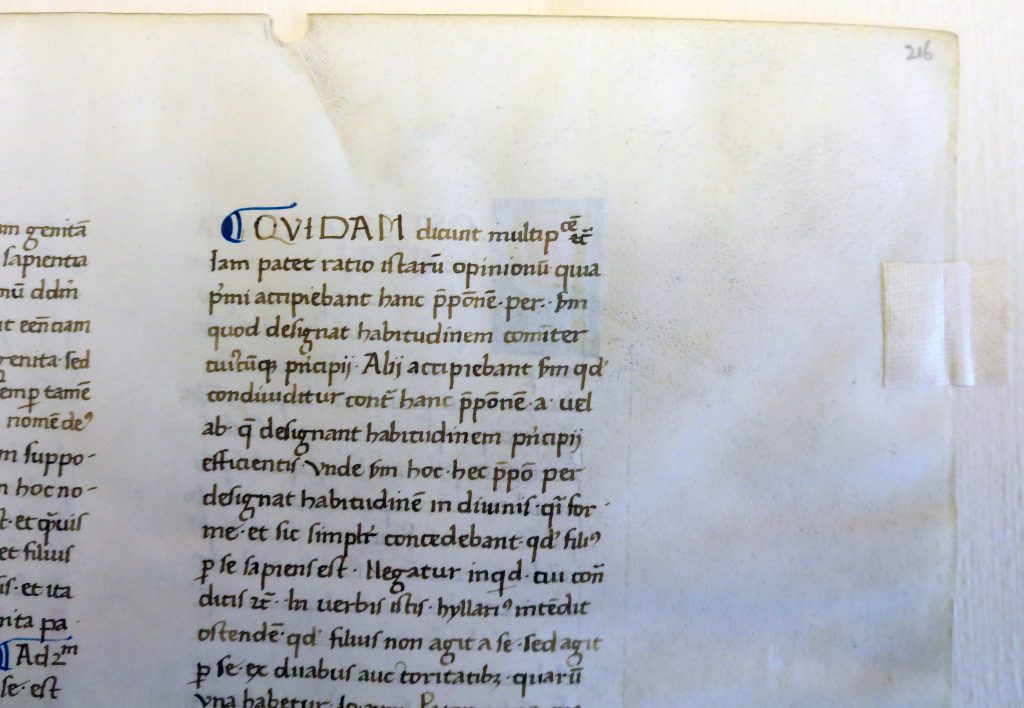

Folio 216. This leaf is turned back-to-front, as hinged to the back board of the mat.

[2331] Super Sent., lib. 1 d. 32 q. 2 a. 2 qc. 1 co. ([etiam sapientia] / genita dicitur), to

[2341] Super Sent., lib. 1 d. 33 q. 1 a. 1 arg. 2 (essentia divina / [est paternitas])

— via http://www.corpusthomisticum.org/snp1026.html and http://www.corpusthomisticum.org/snp1027.html

Let us examine the leaves one by one, starting with the second.

Specimen 2: Folio 216

As mounted in the mat, the leaf turns its original recto to the back.

The Original Recto

The modern folio number stands at the top right. Ege’s mounting strips attach this side to the mat, away from front view.

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, MS 40, Specimen 2 = folio 216v (turned to the front in Ege’s Mount: Top Left. Photography Mildred Budny.

The Original Verso

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, MS 40, Specimen 2 = folio 216v (turned to the front in Ege’s Mount). Photography Mildred Budny.

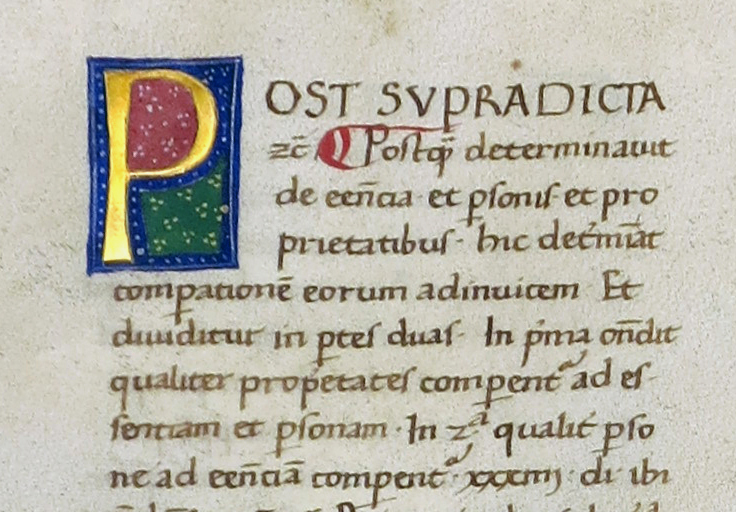

The illuminated initial P (for Post) at the top of the verso opens Distinctio 33 with its Prooemium (“Preface”):

[2338] Super Sent., lib. 1 d. 33 q. 1 pr. — online via http://www.corpusthomisticum.org/snp10033.html.

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, MS 40, Specimen 2 = folio 216v, Top Left. Photography Mildred Budny.

In the process of copying, the scribe left a blank space at the beginning of a line (line 7) in column a. Thus:

probatur proprietatem non esse in essencia ibi . . . hereticorum inprobitas

— compare, for example, [2338] Super Sent., lib. 1 d. 33 q. 1 pr

— via corpusthomisticum.org/snp1033.html.

Presumably here the scribe found the exemplar difficult to decipher, defective, damaged, or itself with a gap. No effort is visible on the page that any remedy was found, or conjectured, and supplied. The gap remains empty across time.

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, MS 40, Specimen 2 = folio 216v (turned to the front in Ege’s Mount): Top of Textblock. Photography Mildred Budny.

The Parchment

The leaf carries some damage acquired on the animal skin. The verso is its hair side, with patterns of the hair follicles. A rounded, partly healed hole occurs at the top of the leaf. Part of the hole was cut away when the margin was trimmed.

The Hair Side

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, MS 40, Specimen 2 = folio 216v (turned to the front in Ege’s Mount: Top Left. Photography Mildred Budny.

The Flesh Side

The partly healed hole shows the incurvation of the underside of the skin at its contour. The line of dirt along the top of the leaf attests to the accumulation of dust or grime in storage of the book upright across time.

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, MS 40, Specimen 2 = folio 216r, top center Photography Mildred Budny.

The Lower Margin

The partly healed hole within the lower margin retains one of the animal’s curved, whitish hairs, attached to its edge.

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, MS 40, Specimen 2: folio 216r, Bottom. Photography Mildred Budny.

Specimen 1: Folio ‘1’

On this leaf, the place for a pencil folio number is damaged and cropped. Cropping at the top of the leaf would have removed some portions of the unsightly damage marring the appearance. Perhaps forms of photographic image enhancement might retrieve the form of a folio numeral, if the leaf had one.

To judge by the text and title, the leaf opens Aquinas’ work, so that it might have been counted as Folio 1. If or when other leaves from the front of the book surface — such as the following leaf in the text (continuing the Prooemium) or a preceding leaf or set of leaves with prefatory or other matter, such as a frontispiece and endleaves — the number for this one might become known within the consecutive sequence. Until then, let us call it Folio ‘1’.

The Recto

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, MS 40, Specimen 1 revealed below the Mat. Photography Mildred Budny.

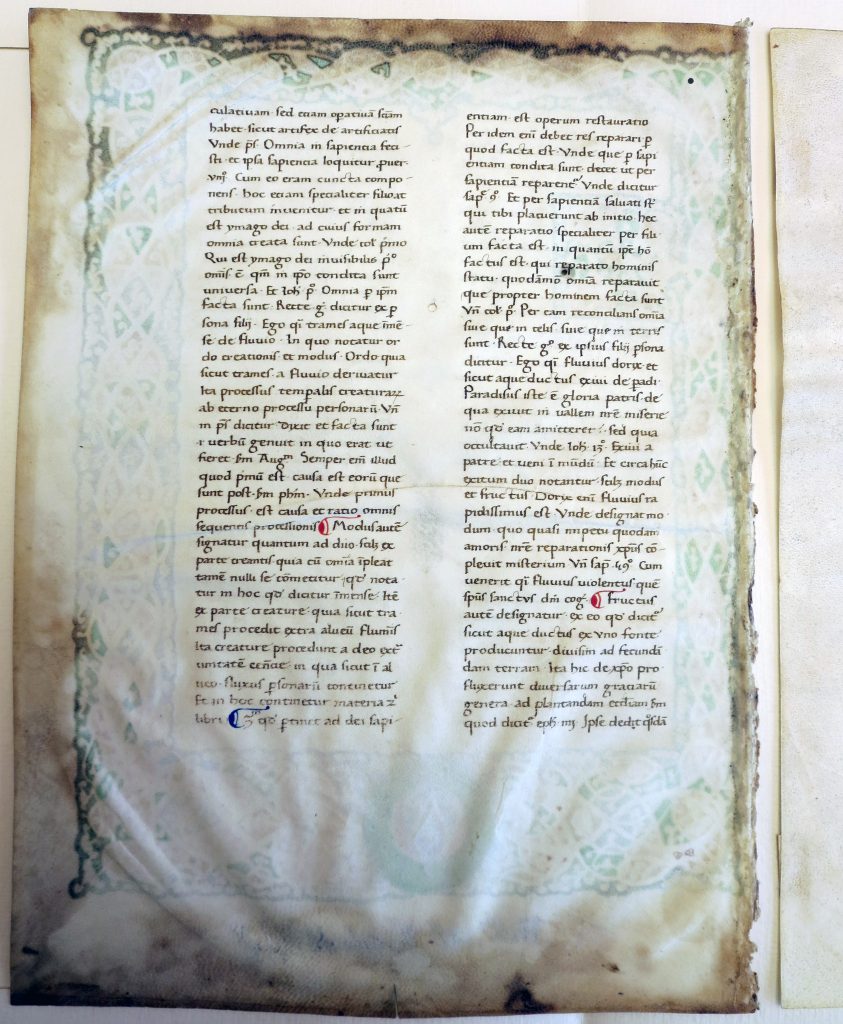

The Verso

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, MS 40, Specimen 2: folio ‘1’v. Photography Mildred Budny.

Show-through from the front of the leaf affects the appearance of the verso. Through moisture and exposure, some portions of the pigments, especially along the edges, have darkened to spread their shadows upon its expanse.

A rounded hole appears in the intercolumn between line 13 of both columns of text. If, say, a wormhole, it would derive from insect behavior affecting the adjacent wooden board of the binding. If so, the leaf or leaves formerly following this one would presumably share this feature.

The Framed Opening Page with Wreathed Arms of an Owner

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, MS 40, Specimen 1: folio ‘1’r, Top. Photography Mildred Budny.

Opening the Text

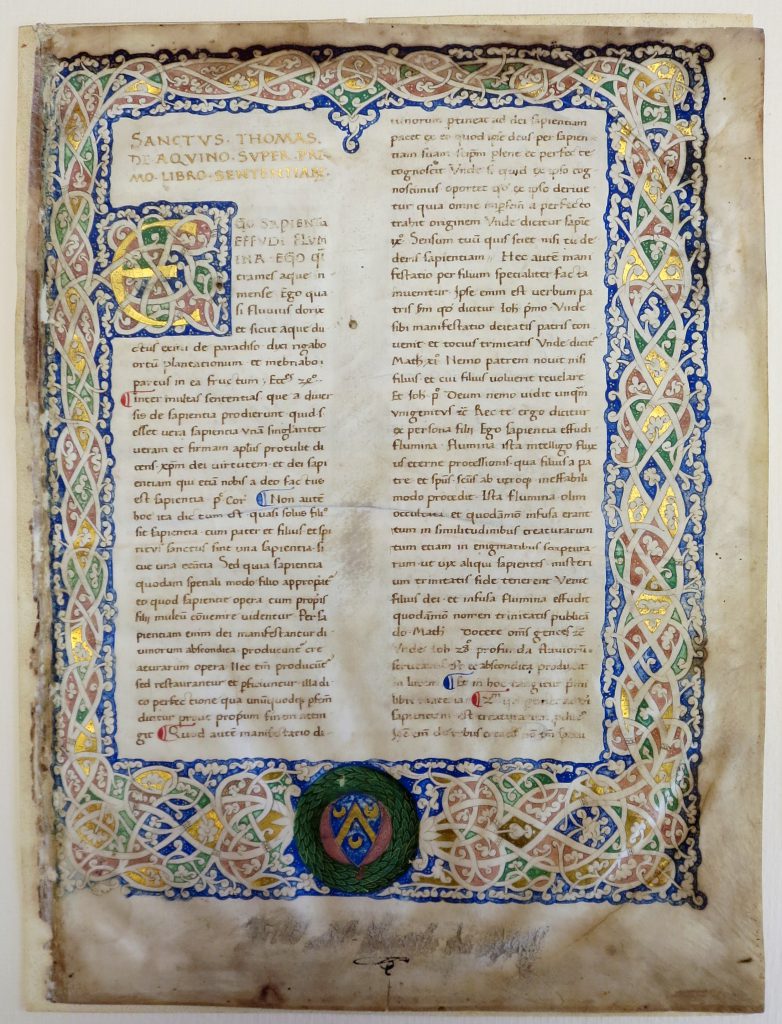

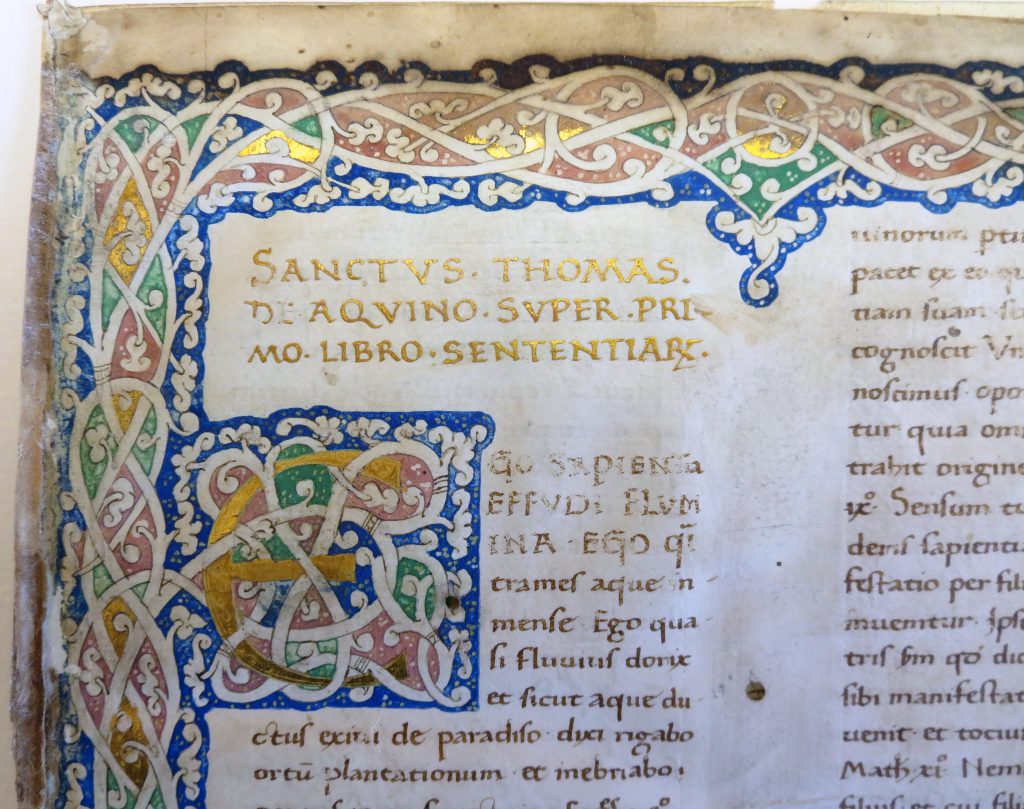

The text begins with its title, written gold pigment in 3 lines of Capitals, and pointed with low or median dots to function as word separators, in monumental style.

SANCTVS ⋅ THOMAS ⋅

DE ⋅ AQVINO ⋅ SVPER ⋅ PRI-

MO ⋅ LIBRO ⋅ SENTENTIAR[UM] ⋅

(“Saint Thomas de [from] Aquino, ‘On the First Book of Sentences‘ “.)

But for an abbreviation of Sanctus and an alphabetical inversion of the surname, this formula is repeated exactly in a pair of sales catalogues of 1925 and 1926 issued by the firm of Davis & Orioli, of London and Florence when offering the manuscript for sale, binding included. To judge by their database record (I have not yet seen the catalogues themselves), each iteration of the catalogue describes the item as

“Aquino (S. Thomas de)”, Super primo libro sententiarum”, XVth century, parchment (fine vellum), Italy, 310 folios, 37 lines, 2 columns.

— SDBM_262153 for 1925 and SDBM_261433 for 1926

On these catalogues, as well as some others, see Otto Ege’s Aquinas Manuscript in Humanist Script (Ege Manuscript 40) and below.

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, MS 40, Specimen 1: folio ‘1’r, Top Left. Photography Mildred Budny.

Three more lines of gold Capitals follow, as the script transitions to the main text written in ink in Humanist minuscule.

Below the title, the Proeemium or prelude of the work begins in the first person: Ego sapientia effudi flumina . . . (“I, Wisdom, have poured out rivers”), in a citation from Ecclesiasticus 24[:40], as identified at its end (in line 10). The rounded initial E of Ego stands apart, enclosed within an inset 8-line panel-like extension of the full-page foliate frame around the columns of text. Built up in gold pigment with band-like rims, the initial interlaces with the network of branching foliate stems which both form and fill the trellis-like frame. Segments of the background between and around the stems are painted with alternate colors of pigment: gold, green, rose, and blue. The blue pigment has darkened, through exposure, along the upper edge of the framework. Rounded spots or dots enliven the background in single or triangular patterns.

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, MS 40, folio ‘1’r, Center Left. Photography Mildred Budny.

The foliate stems and their terminals are rendered in pen-line outlines, which leave their components ‘reserved’ in unpainted, or bare, vellum. That is, they are ‘bare’ apart from some pen-strokes which define certain features. Banded and sometimes ‘pearled’ collars drawn in ink stretch across some stems approaching their branching points. Some collars seem to comprise additions by a different hand and ink, in somewhat ungainly versions. As such, they could comprise added scribbles or sketches responding to, and augmenting, the existing design.

“White Vine-Scroll Ornament”, Humanist Book-Production, and Decorated Bindings

The form of foliate decoration, left in ‘reserve’, unpainted, corresponds with the distinctive style of “White Vine-Scroll Ornament”, or bianchi girari (“white-vine meanderings”), which flourished in Italian manuscript production in the 15th century and beyond. Selected specimens from a variety of manuscripts and centers of production, now gathered in one major institution, appear in the expert survey of Illuminated Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, 2: Italian School, by Otto Pächt and J. J. G. Alexander (Oxford: Bodleian Library, 1970). The sections on “The Fifteenth Century” (pp. 21–96) are arranged by locations, where known (“Florence, Tuscany, Umbria”, “Rome”, “Naples”, “Ferrara and Mantua”, “Venice”, etc.), up to “Central, South, and Unlocalized”.

Pending the discovery or uncovering of information within the fragments of the original manuscript as they emerge, directly leading to the identification of its date and place of production and its original ownership, stylistic comparisons with related cases of script, decoration, and other features will have to suffice.

Without embarking on a detailed study, I offer a few cases, similarly expert, for comparison.

1) A Livy Manuscript in New York from Naples

A similar example of such ornament, along with Capitals written in gold pigment, appears on the opening page of a late 15th-century manuscript of Livy, Ab Urbe condita (“From the Founding of the City”), written and illuminated in Naples.

- New York, Pierpont Morgan Library and Museum, MS M. 476.

The arms of the first owner are erased from the title page. The book, with 255 leaves, retains the “original wooden boards and stamped leather”. Perhaps the surviving structure of the binding resembles the former volume containing the Aquinas manuscript, as described in a sale catalogue (see below)?

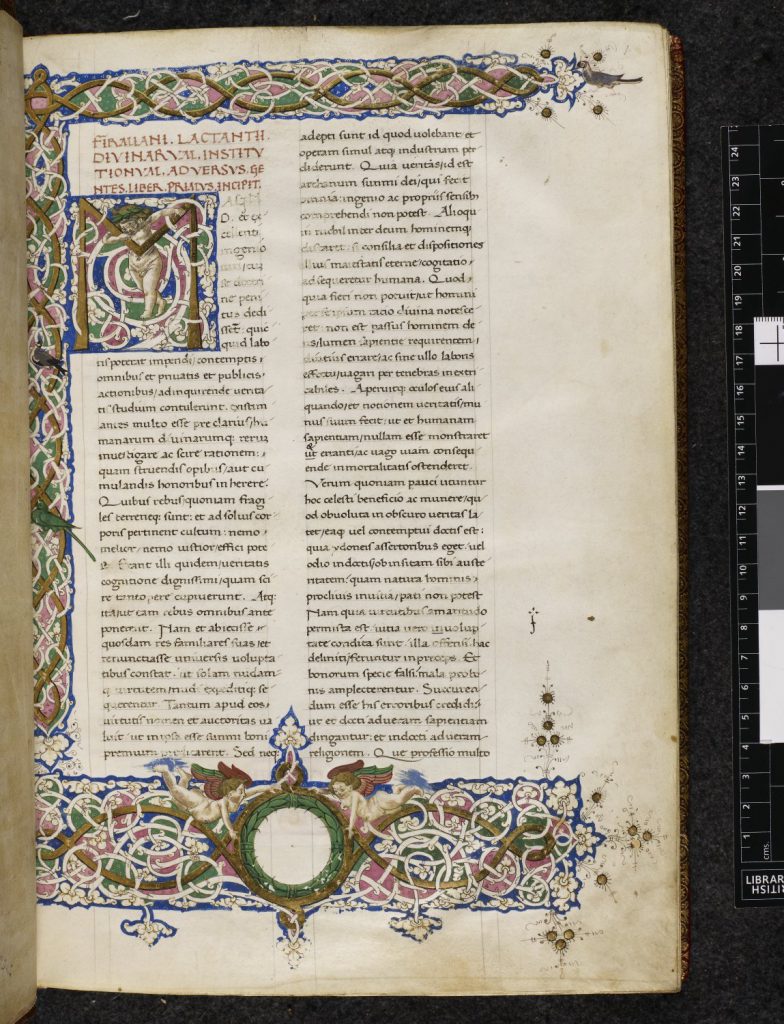

2) A Lactantius Manuscript in London from Florence

- London, British Library, Harley MS 3110.

The first page of this manuscript presents a full-page 3-sided polychrome frame of “white vine” ornament, which includes a panel extension containing the inset 10-line initial M (for Magno), below the 4-line title in gold Capitals. The page opens the text of Divinae institutiones by Lactantius (c. 250 – c. 325), in a copy of a group of the author’s texts made apparently in Florence. Dating from the 2nd or 3rd quarter of the 15th century, the manuscript was written by a known scribe, who lived from circa 1389 to 1468.

© The British Library Board. Harley MS 3110, folio 1r. Opening of Lactantius’ Divinae institutiones.

Unlike the Aquinas manuscript, the foliage includes images of birds and putti, some of the foliate strands are painted in gold for structural effect, and the wreath at the bottom awaiting a heraldic motif remains blank.

Another Lactantius manuscript, Schøyen MS 1369, known as the “Tanaglia Lactantius”, offers a similar frame (albeit with a dog) and an empty wreath to open Book I of the same text, in a copy written in Florence circa 1420–1430 by a named scribe as well as other scribes.

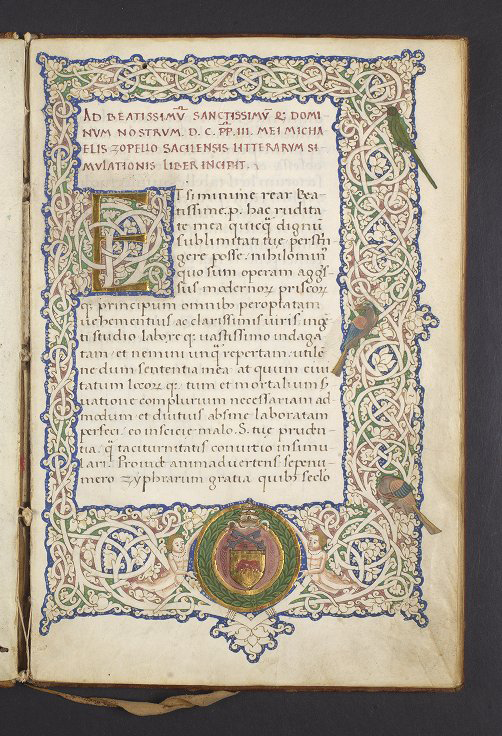

3) A Cryptographic Manuscript in Philadelphia from Rome or the Papal Court

- Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Libraries, Lawrence J. Schoenberg Collection, LJS 225.

A closely datable example of the style appears in a masterful manuscript on cryptography, the Literrarum simulationis by Michele Zapello now in the Lawrence J. Schoenberg Collection. The copy was made (in Rome?) for Pope Callixtus III (Alfonso da Borgia (1378–1458) during his 3-year reign from 1155 to 1458.

University of Pennsylvania, Lawrence J. Schoenberg Collection, LJS 225, folio 1r.

Like the Ege Aquinas manuscript, the frontispiece encloses an inset gold initial (E of ET), 7 lines high, within the interlacing foliage which forms the full-page trellis-like frame, plus cusped extensions at the corners and along the sides. The bianchi girari ornament is inhabited by parrots perched in the vines at the right, and by paired putti posed at the bottom supporting the wreathed crest of Pope Callixtus. In heraldic terms, or blazon:

or, a bull gules upon a terrace vert, in a bordure or charged with eight flames vert.

The frontispiece has been identified as the work of a German artist known to have worked for members of the Aula Pontifica (“Papal Court”) from 1448: Gioacchino di Giovanni or de Gigantibus (active circa 1450–1485); see also Gioacchino de’ Gigantibus. From his hand there survive masterful frontispieces for various texts.

4) A Homer Manuscript in Cambridge from Italy

Similar approaches pertain to manuscripts made in several Italian regions subject to humanist aims for book production.

For example, the “White Vine Scroll Ornament” employed for initials and foliate frames around them can be seen in manuscripts made within the international circle of Cardinal Bessarion (1403–1472). Within his sphere of patronage there gathered many emigrés from the Byzantine Empire after the Fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453. As Cardinal (from 1439), Bessarion

resided permanently in Italy, doing much, by his patronage of learned men, by his collection of books and manuscripts, and by his own writings, to spread abroad the new learning. His palazzo in Rome was a virtual Academy for the studies of new humanistic learning, a center for learned Greeks and Greek refugees, whom he supported by commissioning transcripts of Greek manuscripts and translations into Latin that made Greek scholarship available to Western Europeans. . . . He is known in history as the original patron of the Greek exiles (scholars and diplomats) including Theodore Gaza, George of Trebizond, John Argyropoulos, and Janus Lascaris. (Bessarion; see also Bessarion).

Among manuscripts from that circle, one which I have studied in detail over some years presents an opening initial with such decoration — even to the undulating outer contour of the azure background for the vine-scroll ornament. Made in large-format on paper, the manuscript presents the works in Greek of Homer and the Posthomerica by Quintus of Smyrna:

- Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 81.

The wreath at the bottom of the front page of text encloses the name Θεοδωρος (Theodoros) in gold capitals, identifiable apparently as Theodore Gaza (c. 1398 – c. 1475), humanist, scholar, and translator. For years, from 1447, this Theodore served as professor of Greek in the University of Ferrara. The Homeric scholia in the manuscript was entered by one of his students, the Byzantine Greek scholar Demetrius Chalcondyles (1423–1511), who oversaw the production of the editio princeps of Homer’s works in 1488 (see Homer Editio Princeps, The Editio Princeps of Homer, and ISTC no. ih00300000).

This Greek manuscript from Bessarion’s circle of humanists received its binding before it left Italy. At an unknown date, it reached the collection of Matthew Parker (1504–1575), Archbishop of Canterbury, who misjudged the age of the manuscript and cherished it as a relic of one of his predecessors as archbishop, Theodore of Tarsus (602–690). The wreathed forename would have prompted that wishful thinking.

The old endpapers, which survive at both front and back on the rebound volume, have a type of watermark apparently characteristic of Italian manufacture. Comprising a six-pointed star above two crossed arrows, the design corresponds to Charles Moïse Briquet’s deux fleches en sautoir (his nos. 6267–6301), which he considered to be essentiellement italien. (Briquet Online. Dictionnaire historique des filigranes.) In particular, the design found in MS 81 closely resembles Briquet’s no. 6295, found in a document written at Florence in 1521–1522. See also our page on Watermarks and the History of Paper.

The style of the former binding of MS 81 (removed and lost in the modern rebinding, apart from those endpapers) might have belonged to a similar style as the binding lost from the Aquinas Manuscript in Humanist Script, to judge by a description of that binding while the Aquinas manuscript was intact. To quote the Davis & Orioli catalogue entries of 1925 and 1926 (see below): its binding was “rich-coloured morocco elaborately tooled in blind to a Veneto-Oriental design heightened with pointillé decorations in gold” (sdbm.library.upenn.edu/entries/261433). A “Veneto-Oriental” design could suit perfectly a product from an international humanist circle.

A Convergence of Influences

Such reference points, by association with named scribes or artists, whose time-frames are known, provide cues or clues in discerning a framework for the likely date-span of Ege’s Aquinas Manuscript.

Ege’s cited date of “1470” for it probably presupposes some information which came to him with, or within, the manuscript. Unless or until that information surfaces, or resurfaces, we have to make do with other means of evaluation. For example, perhaps the artist of its frontispiece, the scribe of the manuscript, and/or the owner of the armorial device might become identified.

Meanwhile, a consideration of the stylistic features and their context may suffice. A prerequisite appears to be the known extend and spread of humanist approaches to manuscript production and decoration in Italy and, it may be, beyond.

The Arms, the Wreath, and the Erasure

In the Aquinas manuscript, unlike the Livy manuscript in Washington, D. C., it was not the owner’s arms but an inscription below it which had to be subjected to erasure. Presumably, as customary for inscriptions in such a place, it declared ownership by someone or some institution, whose name proved undesirable or imprudent to mention after the book had departed from that collection.

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, MS 40, Specimen 1: folio ‘1’r, Bottom. Photography Mildred Budny.

The Arms

With the emergence of the first leaf of text, it becomes possible to see the very image of the owner’s arms. Close up, the formations of dots, resembling those in the background of the foliage, are visible in the azure ground of the arms.

Previously, it was necessary to resort to a description in sales catalogues. The description resides in layers of citations, with one catalogue quoting another. I know about it through the quotation in the item offering for sale a remnant of the manuscript (32 leaves) at Sotheby’s among Western Manuscripts and Miniatures in London on Tuesday, 26 November 1985, as lot 80. That item quotes the clipping from a sales catalogue (seller and date unknown) which travelled with that remnant of the manuscript. The quotation repeats the form of the owner’s arms as related in the unidentified ‘American’ sales catalogue before the dismemberment of the book. Its description employs specific heraldic terms and syntax to describe – or blazon — the distinguishing features of the owner’s arms (or coat-of-arms). According to the formal language of heraldry, such terms establish a means of representing, and recreating, the features precisely. Thus, we are to expect:

azure, 3 crescents or between a chevron of the same

The terms and their sequence specify the nature and disposition of the colors or tincture, including or (gold), as well as the designs which embody them. Lo:

The Erased Inscription and a Statement of Ownership?

The erasure affects an entry written somewhat expansively across the lower margin, in a line of cursive script which descends somewhat as it progresses. A flourish with a tail underscores the center of the line. It appears to have formed a finishing touch to the inscription, but it did not seem to require erasure, so that its appearance might demonstrate the nature and color of the ink, and the fluidity of the strokes, of the rest of the entry. The erased portion shows the ghostly traces of 5 words, whose contents could emerge under image enhancement.

The erased inscription in the lower margin remains enigmatic. Enhanced forms of lighting may aid decipherment. Here is a view under directed Black-Light.

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, MS 40, Specimen 2 = folio ‘1’r, bottom center, under Black Light. Photography Mildred Budny.

Parts of the inscription are discernible. It appears to read something like:

Hic est Karolo de Athol

[The most likely parts are “. . . est Karolo de . . . “]

The personal name Karolo or Carolo is recorded in multiple medieval sources. Holders of the name included kings, emperors, and nobles, among others, in many lands. The element de (“from” or “of”) appears to point toward a place-name or surname — similar to Thomas de Aquino in the title at the top of the page. Could the name in this case be related to the place, region, and name Atholl (or Athol) in Scotland?

Does the statement designate an element of possession or attachment (“This or Here is”), whether as ownership of the book, an identification of the arms, or the record of a visit? What was it about the inscription that induced the attempt to efface it?

****

A Note on Sales Catalogue Descriptions

I offer a reminder from our earlier blogpost (Otto Ege’s “Aquinas Manuscript in Humanist Script”), now that the first leaf of the manuscript joins the conversation. Let us briefly revisit the pair of sales catalogues — known to us so far only through a database record of some elements —for the manuscript of 310 leaves, binding included. The elements of their entries are recorded here:

- J. I. Davis & G. M. Orioli, No. 41 (1925), Rare Books & Interesting Manuscripts, Lot # 4. Price 65.00 GBP [Etc.]

(sdbm.library.upenn.edu/entries/262153) - J. I. Davis & G. M. Orioli, No. XLIV (1926), Early Printed Books: Literature, Science, and Medicine, Lot # 1. Price 65.00 GBP [Etc.]

(SDBM_261433)

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, MS 40, Specimen 1 revealed below the Mat. Photography Mildred Budny.

That the firm of Davis & Orioli (see also Davis & Orioli) had offices in Florence, Italy (after 1910), and in London (after 1913) allows to wonder if the volume came to the firm from some source directly in Italy. Perhaps the vellum copy of Aquinas’s commentary on the Sentences, Book I — written in 2 columns of 37 lines, containing 310 leaves, carrying a blind-tooled and gold-decorated leather binding, and containing an owner’s coat-of-arms — resided in Italy for several centuries between its production in the 15th century and its departure for other lands at the start of the second quarter of the 20th century.

The catalogues for the book as a whole indicate that, as reported, the total number of leaves could vary somewhat as the book travelled. On the one hand, 310 leaves according to the SDBM database entries for the 1925 and 1926 catalogues of Davis & Orioli. On the other hand, according to the Sotheby’s catalogue of 1985, the accompanying clipping from an “American bookseller’s catalogue” of an unknown date mention 309 leaves. Who can tell, at present, if that slight difference in counting represents a divergent or inconsistent approach to counting manuscript leaves and endleaves, or signifies the removal of 1 leaf between the time of the Davis & Orioli sales catalogues and the arrival of the manuscript in the hands of a next bookseller, perhaps in America or aiming for the American market?

It is worth wondering whence Ege acquired his varying assessments of the date of production of the manuscript as “1470”, tout court, or as “Late XVth Century”. For example, might the manuscript have carried a colophon or some other evidence for the date? Would such a feature have stood at the end of the book, on a leaf now lost (or lost track of)? What if it would name the patron as well as the maker(s)?

Catalogues and Possible Misprints

Part of the trail may be traced in the sales catalogues which travelled with the manuscript or emerged in the early stages of its distribution as fragments.

In my first blogpost on the manuscript, I knew about, but had not yet seen, the pair of Dushnes catalogues. Now, thanks to the kind help of Meghan Constantinou and Scott Ellwood of the Grolier Club, and Leslie French, it has become possible to see the texts, which deserve scrutiny. Quoting them here, I signal several parts in red.

- Philip C. Duschnes, Catalogue 53: 101 Original Leaves & Sets of Leaves from Medieval Manuscripts, Incunabula, Famous Bibles and Noted Presses, 1150 A. D. – 1935 A. D. [Autumn, 1942), item 50 (p. 9), in the group of “Manuscript Leaves with Miniature Paintings”.

50. 1470 A.D. ITALY. St. Thomas Aquinas’ Commentary on the Sentences. Vellum (11 × 8 1/2 inches). Written in fine humanistic book hand, with initial letters and paragraph marks in red and blue, double columns, 36 lines to the page. It is seldom that we find a religious text written in a humanistic book hand.

$4.00

- Philip C. Duschnes, Catalogue 74: Original Vellum Leaves From Medieval Manuscripts (1946), item 50 (p. 9). For this Catalogue, “All leaves are matted, ready for framing, unless otherwise noted” (p. 3).

50. 1470 A.D. ITALY. St. Thomas Aquinas. Super quarto libro sententiarum. Manuscript (11 × 8 1/2 inches). Double columns, written in fine humanistic hand with red and blue initial letters.

$4.00

Thomas Aquinas’s first great book was this Book of Sentences, a series of lectures on the writing of Peter Lombard. In these dissertations many novel and original theological concepts were logically developed in a maze of subtle shades of thought. This book was universally used as a text book until the end of the Middle Age. Thousands of students based their thesis dissertation on various problems discussed in the compilation. It is seldom that we find a religious text written in a humanistic book hand.

The descriptive statement resembles some parts of Ege’s Labels for his MS 40. Our earlier blogpost considered his Labels in detail. As a reminder, we show them again here.

Ege’s ‘Short’ Label for Leaf 40 in FOL

Otto F. Ege: Fifty Original Leaves from Medieval Manuscripts, Leaf 40, Printed Label, Special Collections and University Archives, Stony Brook University Libraries.

Ege’s ‘Long’ Label for FBNC

Private Collection, Ege’s Famous Books in Nine Centuries, Label for the Aquinas Manuscript Leaf. Reproduced by permission.

While these catalogues demonstrate that distributing dismembered parts of the manuscript individually had begun by their time, and that the explanatory accompanying texts were undergoing formation and variation, the catalogues also indicate that their selection from the Aquinas Manuscript focused upon leaves which did not carry major elements of decoration or illumination, as they offered only initial letters in red and blue, in specimens priced at $4.00 each. At least for the later catalogue, the leaves were matted, as part of the price.

Differences between the 2 catalogues show that the second did not simply copy the first. The companion paragraph in the second catalogue represents a development which points toward, paves the way for, or borrows from Ege’s long Label for the manuscript.

One difference, however, seems puzzling, if not significant.

The first catalogue names the title of the work in English, while the second opts for Latin, amounting to “On the Fourth (quarto) Book of the Sentences”. However, that second, ‘erudite’, version in Latin adds a different numeral to the Book than we have come to expect from its own title and from the surviving leaves of the manuscript itself. Are we to expect that the copy of Aquinas’s Commentary in Humanist Script covered more Books than the First?

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, MS 40, folio ‘1’. Photography Mildred Budny.

I think not.

The testimony of the Davis & Orioli catalogues and the surviving parts of the manuscript itself establish that the manuscript presented Aquinas’s Commentary on the first Book alone. Folio 300 (see above), highest in number so far recognized out of the total reported number of 309 or 310 leaves, still fits squarely within Book I, with more of its text to follow. Unless there emerge more surprises to the contrary, it makes sense to regard the number in the second Duschnes catalogue for the “fourth” Book as a simple error in the counting. If that catalogue entry were all that we had, it might lead us astray in some other direction in the hunt for remnants from Ege’s Manuscript 40. But it isn’t.

While here, let’s note that it can be useful to examine ALL the sales catalogues that are cited in sources, even the seeming ‘repeats’ from a single seller within a closely-spaced set of years. As we see from the 2 Duschnes cases, they can tell different stories, which might add or detract from the accumulated core of information which their records and the manuscript evidence provide. In combination with the other sources of knowledge about the monument, the individual witnesses’ versions can be tested, interrogated, and, where necessary, discarded – but for reasons.

In sum, the testimony of sales catalogues can be invaluable, but they both call for and require analysis of their unique evidence, which may have the merit of facing the original materials directly — sometimes at a time before the material itself disappears from view or becomes otherwise lost, fragmented, and transformed.

A meeting between the catalogue descriptions, other parts of the manuscript, and the opening leaf of the text paves the way for further discoveries about the manuscript and its context. Perhaps soon research will tell us more closely where and when the manuscript was made, from which exemplar it derives (and in what script), who owned it at different stages in its history of transmission, and where more of its parts have wandered.

Harvard University, Harvard University, Houghton Library, MS Typ 995, recto = Ege MS 40, folio 243 recto.

Convergences and Conduits

All in all, the cluster or convergence of influences which gave rise to the creation of Otto Ege’s Aquinas Manuscript in Humanist Script — containing elaborate “White Vine-Scroll Ornament” for the headpiece, an owner’s device in its wreath, a text copied in humanistic script, and a binding in “a Veneto-Oriental design” — probably drew from a range of sources within cultivated spheres bringing together multiple elements and directions. Whether prepared as part of the original production of the manuscript, or added to it for its owner after departing thence, the Veneto-Oriental style would presumably correspond with influences ranging beyond Italy to a wider, eastern sphere as found, and formerly found, in Byzantine realms.

Such symptoms do not necessarily show where the Aquinas manuscript was produced. Instead, they exemplify a range of centers and types of texts which generated books written in humanist script, augmented with with Capitals, embellished with White Vine-Scroll Ornament for initials and trellis-like frames, and endowed with wreaths prominently to display the owner’s arms.

The point is that a formidable range of influences, sources of inspiration, and exemplars for texts, scripts, and embellishments, gave shape to this book. For whatever reasons, Aquinas’ text called for a ‘humanist’ commission to prepare an elegant copy. That fact elicited some surprise from Ege and from Duschnes, partners in fragmenting and distributing it as well as other books.

Whatever the reasons for the commission, to judge by its pages which (so far) are clean of marginalia or corrections, this book was scarcely read. Its fate in reaching the United States, however disrupted in dispersal, curiously enabled it to attain wider recognition and attention through sales catalogues, collections, and the study of manuscript fragments — Ege’s included.

*****

We thank the owner for sharing photographs of the ‘new’ set of the Famous Books Portfolio, and for permitting us to publish them in this and other posts. We also thank the owners and staff of many other collections for access to the materials and for advice about them.

Raymond Clemens, Diane Ducharme, and the staff of the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library give help at many stages in research on aspects of the Otto Ege Collection and other manuscripts. Lisa Fagin Davis continues to share information and discoveries about her own and others’ research. Meghan Constantinou and Scott Ellwood of the Grolier Club and Leslie French of the Research Group on Manuscript Evidence generously help to give access to the Duschnes and other sales catalogues. Thanks are due to many colleagues, students, and friends who have offered suggestions, corrections, and advice.

Watch this blog for more reports. See its Contents List.

*****

Do you know of more leaves from this manuscript? Of other sets of the Portfolios of Famous Books (in Nine and/or Eight Centuries)?

Do you have suggestions for the date and origin of this manuscript? Do you know of other works by the scribe(s) and frontispiece artist? Can you identify the owner of the arms? Can you read the erased inscription?

Do you know where we might access the entries for the sales catalogues by

- J. I. Davis & G. M. Orioli, No. 41 (1925), Rare Books & Interesting Manuscripts, Lot # 4

- J. I. Davis & G. M. Orioli, No. XLIV (1926), Early Printed Books: Literature, Science, and Medicine, Lot # 1?

Please let us know. Please leave your comments here, Contact Us, and/or visit our Facebook Page. We look forward to hearing from you.

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, MS 40, Specimen 1: folio ‘1’r, Top Left. Photography Mildred Budny.

*****

Thanks for sharing your great informative post on your post…

Thank you for your comment. This manuscript called to me, and the research was a labor of love.

Excellent article!

You may like to know there is another leaf from this manuscript to add to your collation. The leaf foliated ‘220’ in pencil in a later hand is in the collection of the State Library of South Australia. I have added a description and transcription in Fragmentarium https://fragmetarium.ms/overview/F-xcta The text from Book I, beginning partway through d. 33 q. 1 a. 3, directly follows on from the leaf (foliated 219) held in Granville, OH, Denison University, William Howard Doane Library.

Dear Rose,

Fantastic! Delighted to learn of your discovery! A new blogpost will acknowledge your discovery, with thanks!

Best wishes,

Mildred Budny