Otto Ege’s Portfolio of ‘Famous Books’ and ‘Ege Manuscript 53’ (Quran)

January 27, 2021 in Manuscript Studies, Uncategorized

Ege’s Famous Books in Nine Centuries

and

A New Leaf from Ege Manuscript 53

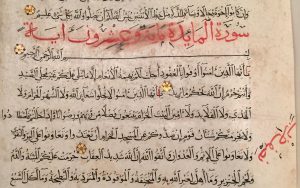

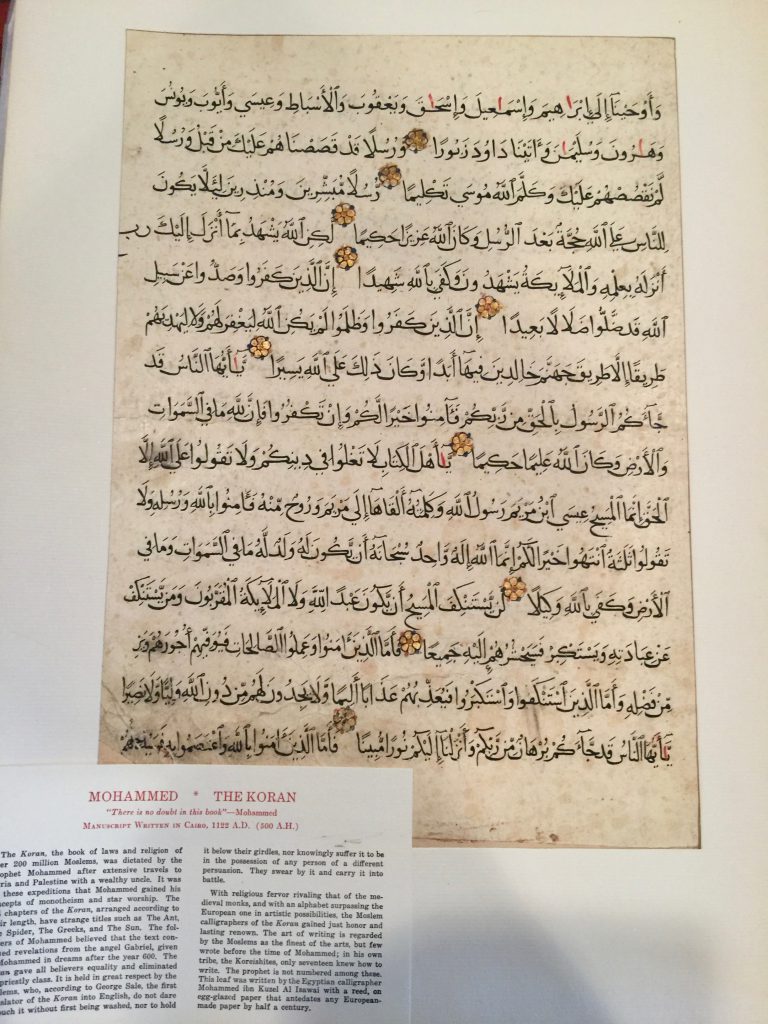

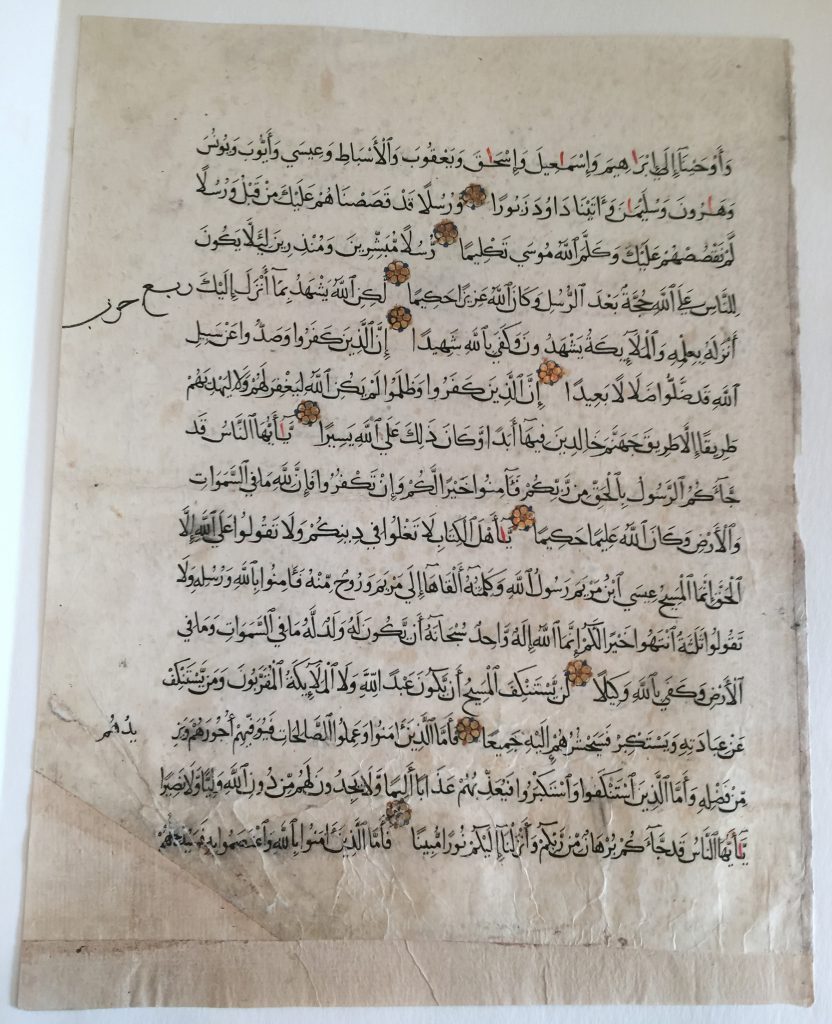

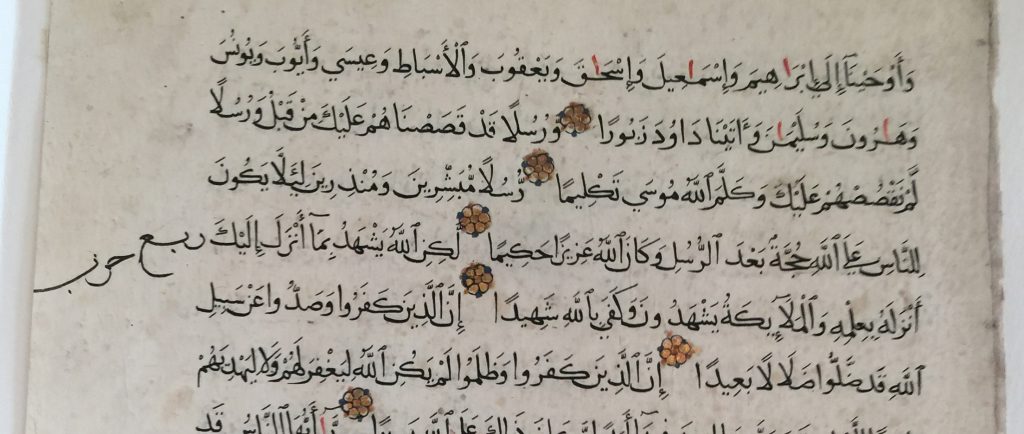

Qur’an or Koran written in Arabic on paper

Egypt, dated 1122 CE (500 AH), but later: Probably Mamluk Dynasty, 14th or 15th Century

Circa 391 × 299 mm <Written area circa 285 × 220 mm>

Single column of 15 lines in Arabic

Surah 4:163 – Surah 5:4

With rubricated titles, textual dividers, and rosettes for verse markers

Private Collection, Koran Leaf in Ege’s Famous Books in Nine Centuries, Back of Leaf, Detail. Reproduced by permission.

[Published on 27 January 2021, with updates]

Here we begin to showcase a newly revealed set of one of the Portfolios of specimen Leaves from books and manuscripts assembled by Otto F. Ege (1888–1951). This set presents a selection of specimens of Famous Books, in the longer, or deluxe version, of Nine Centuries. The shorter version covers Eight Centuries.

The version in Nine Centuries was issued in 50 sets, with 40 specimen Leaves extracted from manuscripts and printed books. The shorter version in Eight Centuries was issued in 110 sets of 25 Leaves.

In earlier blogposts, some sets in both versions have come into our view — mainly on account of the specimens from a 14th-century manuscript in Latin on paper with Aristotle’s Nichomachean Ethics or its commentaries. Our study of that manuscript began with an isolated leaf in a private collection, then moved to examine more of its relatives surviving elsewhere.

Kent State University Libraries, Set 47 of Otto Ege’s Portfolio of ‘Famous Books’, Aristotle Leaf, detail: ‘Genus dividitur in genus’. Reproduced by permission.

Now, we consider the Portfolio in Nine Centuries as such more fully, in the light of the ‘new’ set. This post first examines the nature of the Portfolio (and its fraternal twin in Eight Centuries), then turns to look at its Leaf 1, extracted from a Quran/Koran manuscript in Arabic on paper. That manuscript presents its text in single columns (unframed) of 15 lines, with some rubricated elements and embellishments in gold and other pigments.

Further posts may examine other leaves in the Portfolio, in their manuscript and printed forms.

Broad in vision, the range of specimens come from religious and secular texts over the course of centuries and from a wide range of places of production. As an indication, see Ege’s Contents List (shown below) and his individual Labels for all 40 specimens — displayed online from another set (at Case Western University).

The specimens represent texts in various languages (mostly Western) and by many notable, and even world-class, authors. Represented in their own language or another, they include Homer, Aristotle, Cicero, Ovid, Pliny, Virgil, Dante, Petrarch, Boccaccio, Erasmus, Chaucer, Cervantes, Shakespeare, Milton, Montaigne, the Beowulf poet, and the translators of the King James Version. The specimens represent many renowned printers in Western Europe and the United States, such as Nicolas Jenson, Aldus Manutius, Robert Estienne, Lucantonio Giunta, Bodoni, the Kelmscott Press, and the Riverside Press. Not forgetting, among others, a specimen from the Nuremberg Chronicle of 1493 and from the Fourth Folio of 1685. A few specimens include illustrations.

The selection and design of the Portfolios of Famous Books correspond both neatly and closely with some central interests of Otto Ege throughout his career. (See, for example, Introducing Otto Ege and Otto F. Ege.) As a long-time teacher of graphic design and the history of the book (and later a Dean) at the Cleveland Institute of Art, and as a graphic designer (and printer) in his own right, here Ege was in his element.

The ‘New’ Set in a Private Collection

The ‘new’ set in Nine Centuries resides in a Private Collection. The owner, noticing our webposts (see their Contents List) and mentioning to us the set of Ege’s Famous Books Portfolio, has kindly taken photographs, which we can show for inspection and research — with our thanks.

The set came from this sale: Fall Fine & Decorative Art Auction on October 4, 2015. It was offered (out of Willoughby, Ohio) by Fusco Auctions as lot 81: Ege Portfolio Original Leaves Famous Books, with an Estimate of $2,500 – $3,000, and a realized price of $2,600.

The online catalogue for the sale of that lot presents 4 photographs of a few highlights. They show views of the Portfolio Front Cover, Ege’s printed full-page Contents List, both sides of the First Leaf (from the Koran in Arabic), and Ege’s printed Label for that specimen Leaf.

The set, unnumbered, contains the full set of 40 specimen Leaves, as cited in the 1-page Contents List printed on a single companion leaf of paper.

Samples of Ege’s Portfolios

Some collections possess more than one of Ege’s Portfolios, dedicated to a variety of focused themes on the arts of the book in manuscript and in print across time and place. The nature and themes of his multiple Portfolios are surveyed in several publications. (See below.)

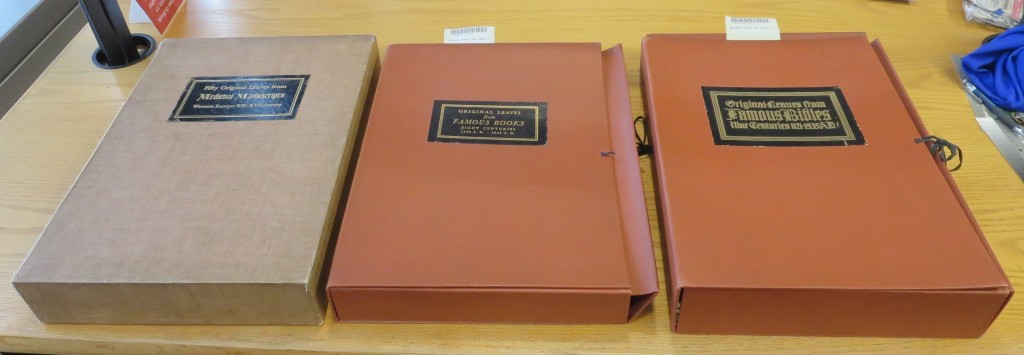

Occasionally, as I have found, it is possible, with permission, to examine more than one of the Portfolios side by side. The opportunity has occurred, for example, at the Houghton Library at Harvard University in Massachusetts and at the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County in Ohio. At the former, the consultation addressed 2 sets of the Portfolio of Famous Bibles; at the latter, 3 different Portfolios — all of which come under consideration for our present purposes:

- Fifty Original Leaves from Medieval Manuscripts, Western Europe (“FOL”)

- Original Leaves from Famous Bibles

- Original Leaves from Famous Books

Three Ege Portfolios. “Fifty Original Leaves from Medieval Manuscripts”, “Original Leaves from Famous Books” (Series A in “Eight Centuries”), and “Original Leaves from Famous Bibles” (Series B in “Nine Centuries”). From the Collection of The Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County. Photograph by Mildred Budny.

Two of these Portfolios, Famous Bibles and Famous Books, were issued in 2 versions, shorter and longer, in Eight Centuries and in Nine Centuries.

For present purposes, another of Ege’s Portfolios also comes into view. It is devoted to

- Fifteen Original Oriental Leaves of Six Centuries: Twelve of the Middle East, Two of Russia, and One of Tibet, amounting to 15 Leaves in 40 Sets.

For that Portfolio, Gwara, Otto Ege’s Manuscripts, Appendix V (on page 103), lists 13 located sets; worldcat.org lists some of these as well as other sets. Some sets can be viewed online, Leaf by Leaf, as with the set in the Brooklyn Museum:

- New York, Brooklyn Museum Libraries, Special Collections, Call Number Z109 Eg7.

Earlier blogposts have considered aspects of all these Portfolios, but for the Oriental Leaves. Within those reports, we have considered in particular Ege MSS 8, 14, 19, 29, 41, 51, and 61, along with Ege’s Workshop Practices. (A post on Ege MS 22 is coming soon.) See our Contents List.

Now, turning to the ‘new’ set of Famous Books, it seems clear that our previous explorations of the several different Portfolios come in handy as background — perhaps especially because there is some cross-over between different Portfolios in Ege’s distribution of individual copies of books and manuscripts. We start with the Koran/Quran manuscript (‘Otto Ege MS 53’), with its specimens found in both Famous Books in Nine Centuries and in Oriental Leaves, as well as elsewhere.

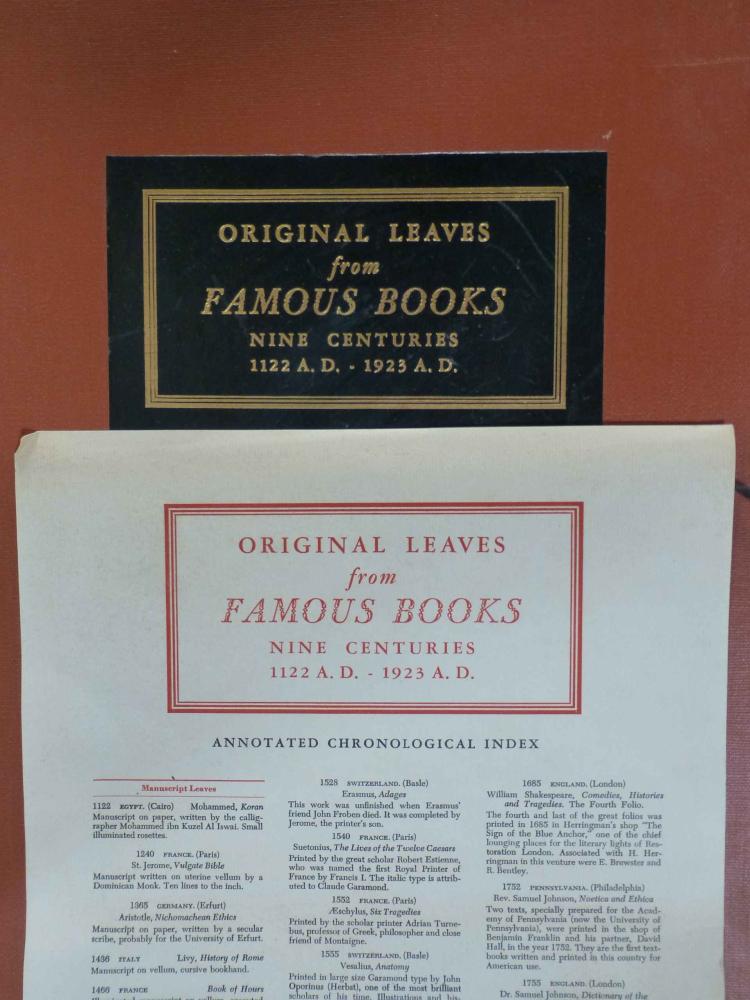

The Portfolio in Question

By the title on its front cover and the Title-Page with Contents List, the ‘new’ Famous Books Portfolio proclaims itself as a set of Original Leaves from Famous Books, Nine Centuries, 1122 A. E. – 1923 A. D., with a List of 40 unnumbered Leaves. This is the longer, deluxe, series in Ege’s 2 versions of the Portfolios of Original Leaves from Famous Books. The shorter version spans only Eight Centuries, 1240 A. D. – 1923 A. D. in 25 leaves.

For short, some sources refer to these Portfolios as FBNC and FBEC, as in Scott Gwara’s account of Otto Ege’s Manuscripts (2013). The close resemblance of these 2 acronyms, differing only partway through (N versus E), may require close inspection. In context, referring to the variants as “Nine Centuries” or “Eight Centuries” might be clearer at a first glance, where concision of space or numbers of characters is not a primary consideration.

Gwara considers these 2 Portfolios as entities on his pages 36–37 and in his Appendixes III and IV (on pages 100–102), which list some current locations of their sets. His “Handlist of Manuscripts and Fragments Collected or Sold by Otto F. Ege” (Appendix X on pages 116–201) lists the manuscripts in numerical order by assigned numbers (1–325 and counting), indicates their position in any of Ege’s Portfolios, and cites current locations, sales catalogues, and other information, as available.

Another invaluable resource for these and other Portfolios, or Leaf-Books, by Ege (and by others):

- Christopher de Hamel and Joel Silver, with contributions by John P. Chalmers, Daniel W. Mosser, and Michael Thompson, Disbound and Dispersed: The Leaf Book Considered (Chicago: The Caxton Club, 2005), Catalog-Checklist no. 14/68 (pp. 74–75 and 116) and no. 20/98 (pp. 79–81 and 120), and Checklist nos. 21 (p. 110) and 51 (p.114)

This book doubles as an exhibition catalogue. It contains a set of essays about Leaf Books in general and in particular, the “Catalog of the Exhibition” (pp. 62–101), and “A Checklist of Leaf Books” (pp. 102–137). That both the Catalog and the Checklist have their own series of numbers (items 1–46 and 1–230 respectively) might prove ambiguous, so reporting their page-numbers as well as their section- and item-numbers can be helpful.

On one opening (pages 81–82), there are illustrated 6 sample plates of “Six leaves from Otto Ege’s 1949 boxed set of original leaves from famous books” in nine centuries (Catalogue number 20 / Checklist number 98), in the collection of Michael Thompson. The sampling shows the specimens of 5 printed books and 1 manuscript — the Koran manuscript which opens the Portfolio. From that photograph of one of its sides (the recto), it is possible to identify its location within the former manuscript.

The Contents

Private Collection, Ege’s FBNC, Title and Headpiece for the Contents List.

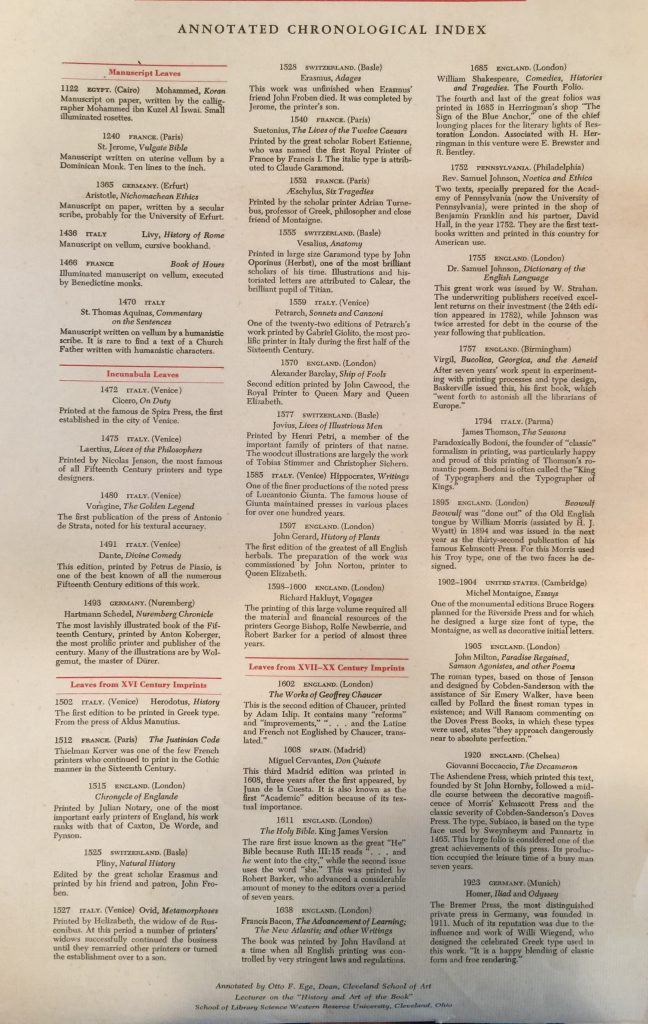

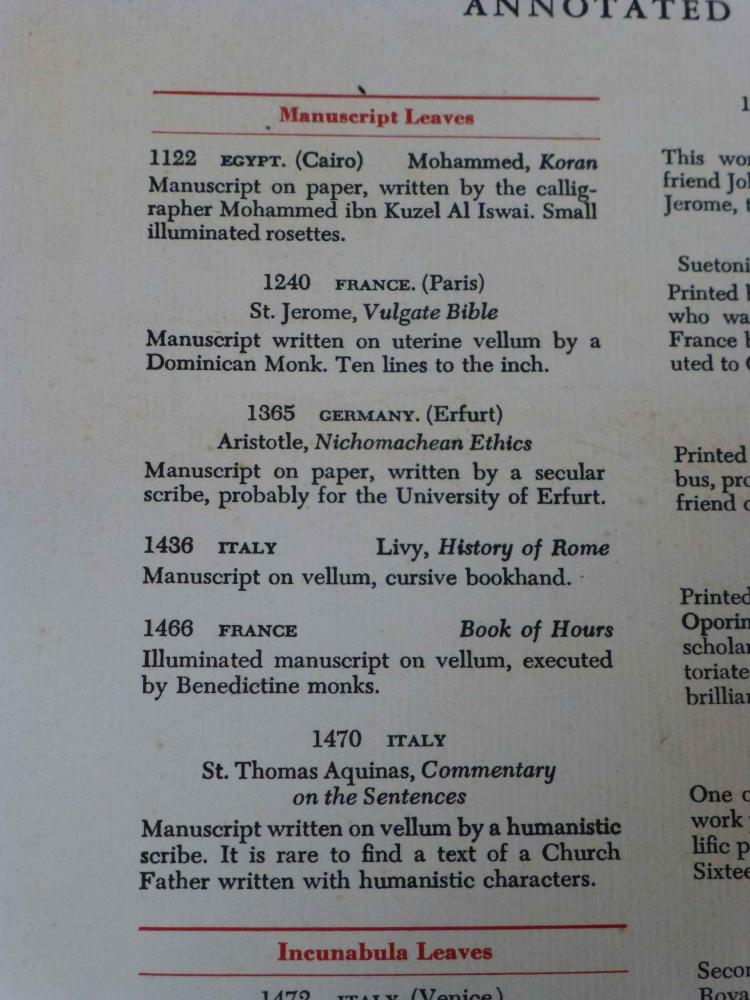

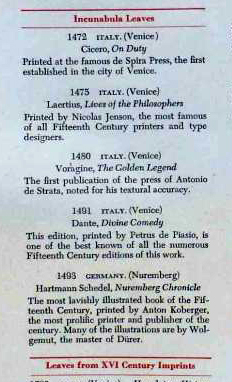

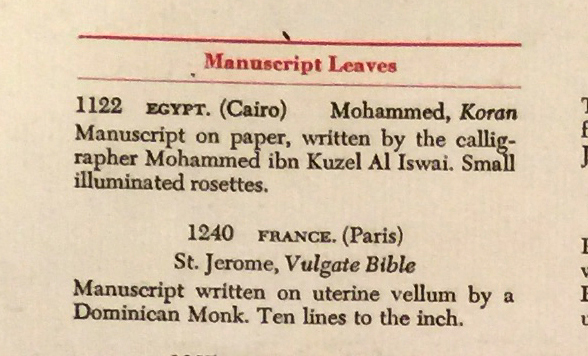

In a single page, Ege’s Contents List, which he called an “Annotated Chronological Index”, arranges the specimens in groups by chronological order and by medium:

- Manuscript Leaves

- Incunabula Leaves, and

- Imprints, in 2 subgroups: XVI Century and XVI–XX Century

Private Collection, Contents List in Ege’s Famous Books in Nine Centuries, Chronological Index. Reproduced by permission.

The 4 groups commence with the Manuscripts.

First the Manuscript Specimens

There are six Specimens in total, with texts all in Latin but for the first in Arabic. (The Portfolio in Eight Centuries has only three — and does not include the Arabic.) They are written variously on paper or on animal skin (parchment or vellum).

Their list:

Note that Ege’s title or summary for each leaf customarily employs a title in English, regardless of the language of the specimen text.

- 1122 Egypt. Mohammed, Koran on paper

- 1240 France. St. Jerome, Vulgate Bible

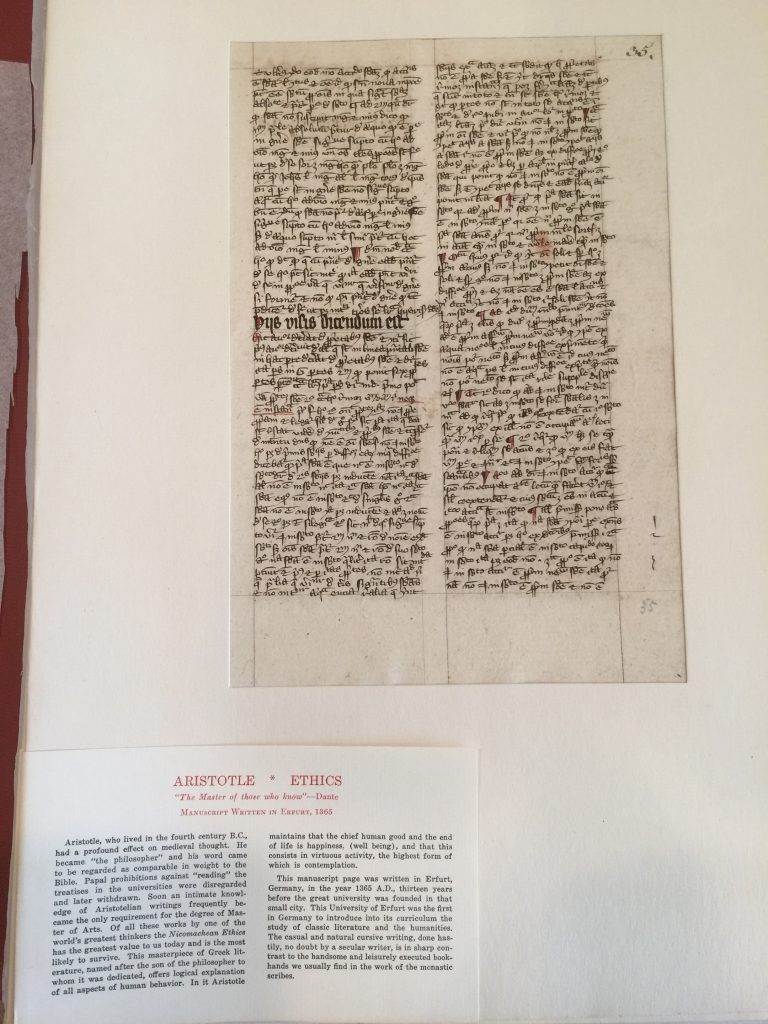

- 1365 Germany. Aristotle, Nichomachian Ethics on paper

- 1436 Italy. Livy, History of Rome

- 1466 Italy. Book of Hours

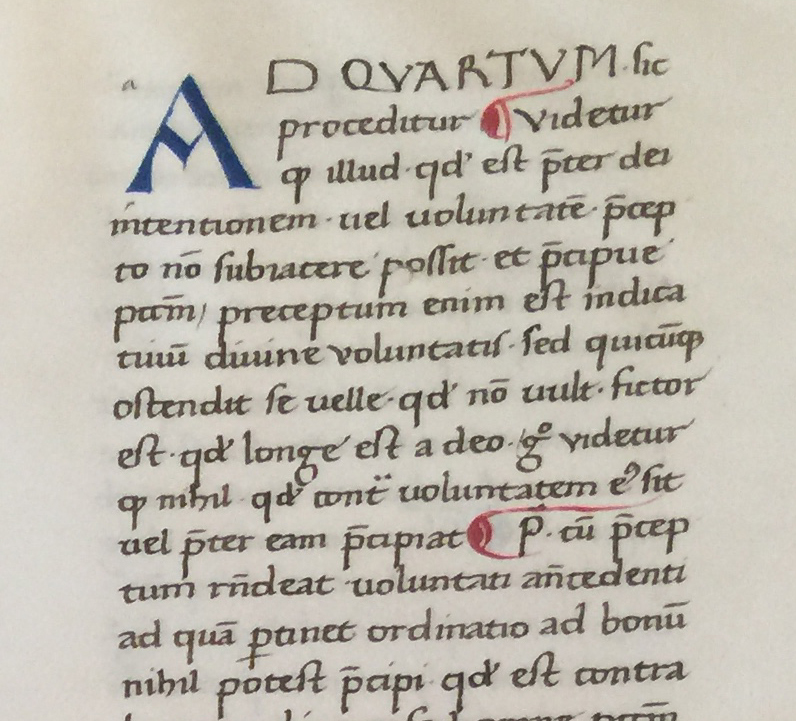

- 1470 Italy. St. Thomas Aquinas, Commentary on the Sentences

That is, according to the numbering assigned to Ege’s manuscripts in Gwara’s Handlist:

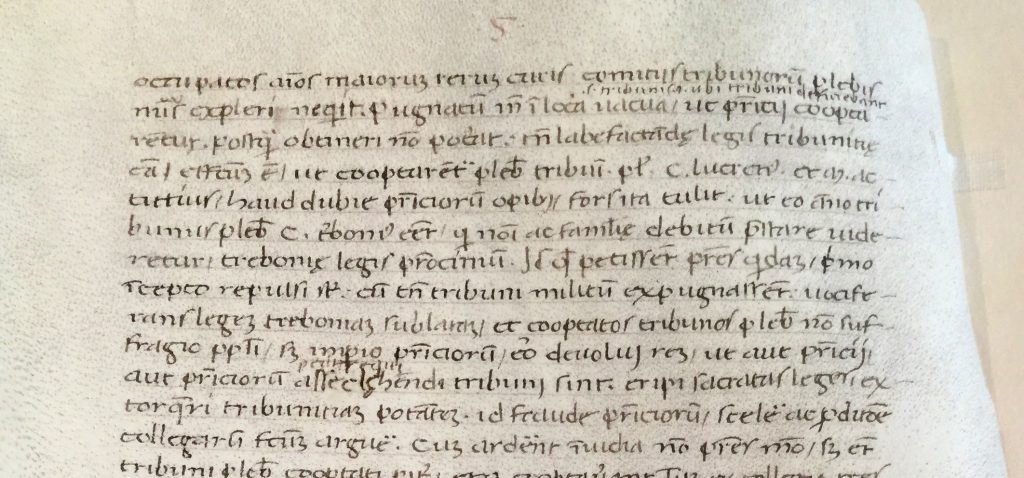

- 1122 Egypt. Mohammed, Koran on paper [ = Ege MS 53, here Surah 4:163 – 5:14]

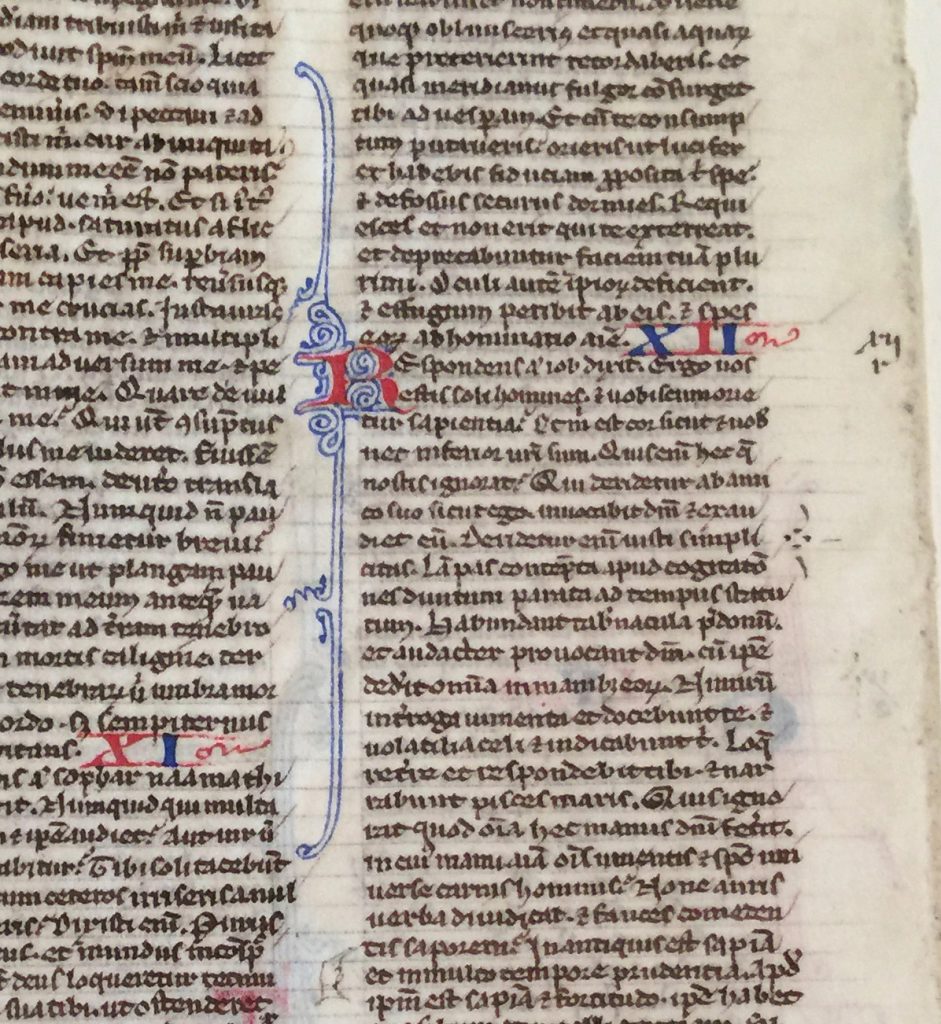

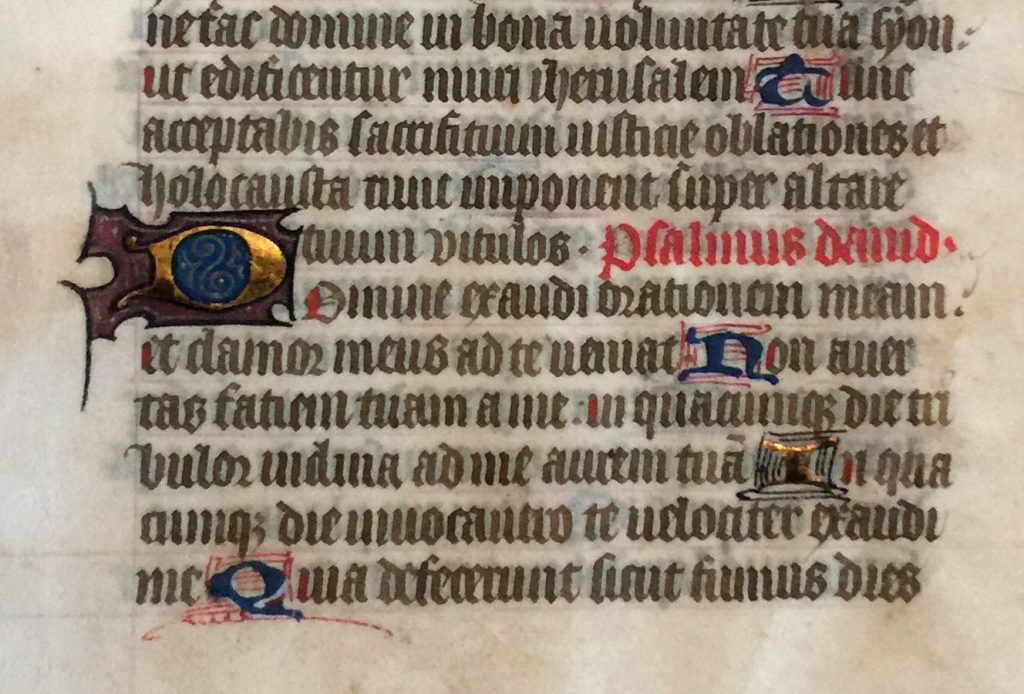

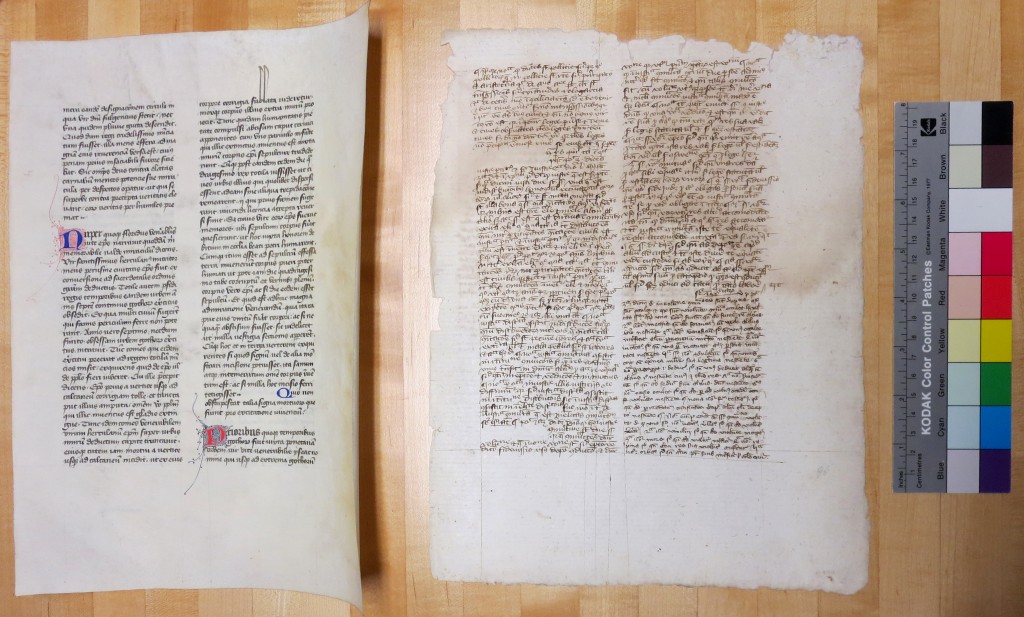

- 1240 France. St. Jerome, Vulgate Bible [= Ege MS 54, here from the Book of Job chapters 8–12]

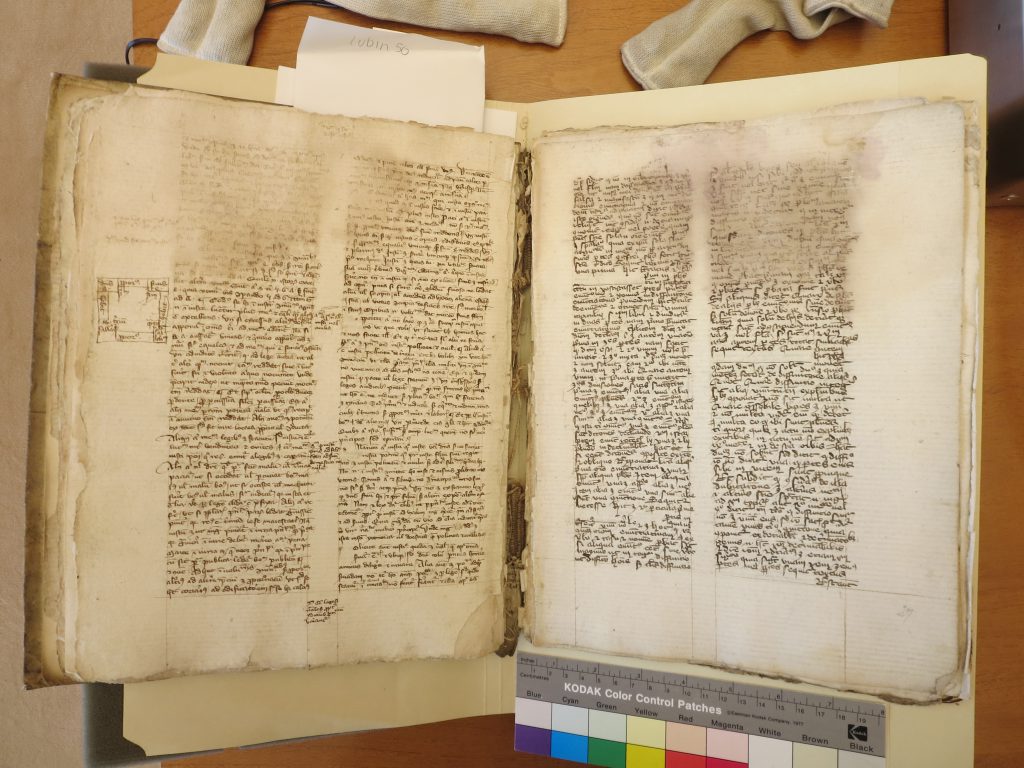

- 1365 Germany. Aristotle, Nichomachian Ethics on paper [= Ege MS 51, here folio 35/35]

- 1436 Italy. Livy, History of Rome [ = Ege MS 52; here folio 41]

- 1466 Italy. Book of Hours [ = Ege MS 55; here folio 53]

- 1470 Italy. St. Thomas Aquinas, Commentary on the Sentences of Peter Lombard [ = Ege MS 40; here folio 300, turned back-to-front in Ege’s mat]

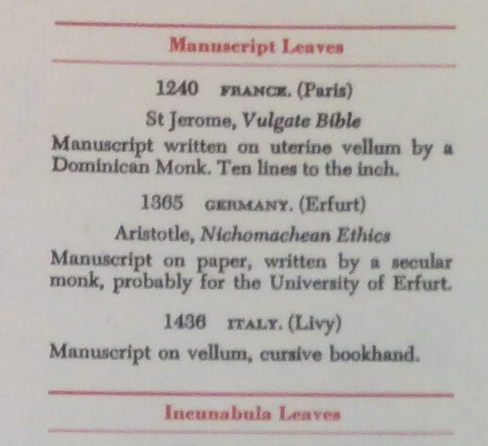

These contents differ somewhat from the selection of Manuscripts in the Portfolio version of Eight Centuries, as seen in its Contents List with 3 Specimens in the set at Kent State University.

Otto Ege’s Contents List of the Manuscripts in his FBEC Portfolio at Kent State University Libraries, reproduced by permission.

Note that the components which Ege assigned to the individual sets of the Portfolio display some variation. A look at individual Portfolio sets reveals certain changes, for which the data have yet to be examined in full, while the process of tracking the Portfolio sets, their dispersal, and their components remains ongoing.

Let us remain aware of the subsequent rearrangements and substitutions which owners might effect. A documented case of such adjustments to the contents by Ege’s widow herself is vividly illustrated in a blogpost by our Associate, Lisa Fagin Davis, as part of her series Manuscript Road Trip, reporting a visit to Cincinnati, Ohio, and to a private collection which holds a set of the Famous Bibles in Nine Centuries, replete with annotated Contents List and substituted Contents (shown here). The recorded replacement substitutes the specimen of one 13th-century Vulgate Bible for another, exchanging, as Leaf 2, a leaf from Ege MS 76 for one from Ege MS 59, and noting the substitution in annotations to the Contents List.

The Spread Across Portfolios

Specimens from some of these manuscripts served within more than 1 of Ege’s different Portfolios. Such is the case with all but the Book of Hours. Some of the selected manuscripts appear in both versions of Famous Books; some appear both there (both versions of the Portfolio in Eight or Nine Centuries) and elsewhere; and some appear in the longer version of Famous Books, as well as elsewhere.

Appearances in 5 ‘flavors’:

1) Some manuscripts served in both versions of the Portfolios of Famous Books, in Nine Centuries and in Eight Centuries (FBNC + FBEC). Such is the case with

- The Aristotle specimen (as Leaves 3 and 2 respectively in these two Portfolios) = Ege MS 51

- The Livy specimen (as Leaves 4 and 3 respectively) = Ege MS 52

Private Collection, Ege’s Portfolio of ‘Famous Leaves’, Livy MS Leaf, Back, Top. Reproduced by permission.

2) Selections from the dismembered copy of the Koran appear in both the Portfolio of Famous Books in Nine Centuries (as Leaf 1) and the Portfolio of Oriental Leaves (likewise as Leaf 1). That is,

- The Koran specimen served as Leaf 1 in both FBNC and the Portfolio of Oriental Leaves = Ege MS 53

3) The dismembered Vulgate Bible of 1240 circulated in both FBNC and FBEC (as Leaves 2 and 1 respectively), although sometimes in FBEC its place was taken by a very similar pocket-sized Vulgate Bible used in the FOL Portfolio as its Leaf 9 ( = Ege MS 9).

- The Vulgate Bible specimen of 1240 = Ege MS 54

Private Collection, Ege’s FBNC Portfolio, Vulgate Bible Leaf, Verso, Mid Right. Reproduced by Permission.

4) The Aquinas specimen in Humanist Script circulated both in the FBNC (Leaf 6) and the more famous FOL (Leaf 40), from which position comes its number in Scott Gwara’s Handlist. Its dismembered Leaves in some FOL sets are illustrated, for example, on the website ege.denison.edu.

- The Aquinas specimen in Humanist Script = Ege MS 40

Note that this manuscript, although distributed in the same 2 Portfolios as the Vulgate Bible manuscript (FBNC + FOL) to which Gwara assigned 2 different Handlist numbers, holds only 1 number in Gwara’s Handlist, corresponding squarely with the position assigned to it in FOL. The differential treatment in the Handlist of the Vulgate Bible specimen on the one hand, with 2 assigned numbers, and the Aquinas specimen on the other can lead to some confusion or conflation. (As observed above.)

Private Collection, Ege’s FBNC Portfolio, Aquinas Leaf, Recto, Top Right. Reproduced by Permission.

5) So far as we know, among Ege’s Portfolios, the Book of Hours specimen in FBNC appears only in this one Portfolio (as Leaf 5).

- The Book of Hours specimen from a manuscript dated 1460 = Ege MS 55 (see Gwara, Otto Ege’s Manuscripts, figure 63 on page 271)

Private Collection, Ege’s Famous Books in Nine Centuries, Book of Hours Leaf, Front, Lower Portion of Text. Reproduced by permission.

All these leaves deserve attention in their own right and in the context of their dispersed relatives. Already some studies consider one or other of them, particularly in the setting of the FOL Portfolio. Examples include the website ege.denison.edu, showcasing “The Ege Manuscript Leaf Portfolios” and exhibiting images from each Leaf (not necessarily both sides) in specific sets of FOL at 14 institutional collections in the United States and Canada.

Printed Leaves

Whereas Scott Gwara’s Handlist in Otto Ege’s Manuscripts (2016) provides the standard for citing Ege’s Manuscripts, apparently there has appeared no comparable Handlist of Ege’s Printed Books — or even of his 15th-century Incunabula — and their distribution patterns and current locations. Efforts toward this goal gather momentum, however, as part of the wider work on Ege’s books and their impact overall.

The full series of Ege’s Labels for the 40 specimens of textual materials in the Portfolio in Nine Centuries is displayed online for some sets, as at Case Western University in Cleveland, Ohio. Set within rectangular borders resembling captions for an exhibition, the printed Labels expand the information in the Contents List into several paragraphs of observations about the genre of book, authorship, impact, and other generic features, with a few comments about the specific book from which the specimen derives.

In Ege’s 1-page Contents List, the 6 Manuscript Leaves (items 1–6) are followed by 5 Incunabula Leaves (items 7–11), then the groups of Leaves from XVI Century Imprints (items 12–26 with 14 specimens) and Leaves from XVII–XX Century Imprints (items 27–40 with 13 specimens).

Alongside the manuscript fragments, the printed specimens in the Portfolio hold interest also in their own right. A special ‘subset’ is their group of leaves from early printed books, or Incunabula.

Private Collection, Ege’s Portfolio of Famous Books in Nine Centuries, Laertius Leaf (1475), Front, Top Right. Reproduced by Permission.

For the printed materials, by definition other copies, more-or-less identical, may survive in other collections retaining the book in full (more-or-less). Some copies are reproduced online in full or partial facsimile. Some copies might still be available for direct inspection in their collections, for loan, or for purchase.

However, Ege’s leaves comprising printed matter sometimes carry marginalia and other forms of additions or alterations — as the case with some of the Incunabula — which ‘lift’ their status into unique witnesses to the transmission of the given book and edition.

In all cases, the patterns of location for the given titles as distributed within given sets (and in other settings) can contribute to the knowledge of Ege’s workshop practices in dismembering books and relocating their isolated elements for broader scattering into very many collections, which themselves might change hands — sometimes more than once. See, for example, A Leaf from ‘Otto Ege Manuscript 19’ and Ege’s Workshop Practices.

A challenge to finding the location and character of other sets of the Portfolio (in one or other version), or perhaps dispersed parts of them, is the tendency of some institutional cataloging practices to separate the individual items into different departments or categories (literally or virtually), and, on occasion, to omit to mention, or to bury, the connection between the given Leaf or Leaves on the one hand and Ege and his Famous Books (or some other) Portfolio on the other.

We have encountered such problems with other parts of Ege’s oeuvre — as we might call his work and his works in the forms of dismembered and repositioned books of many kinds. The problems multiply with the widespread dispersal of the Portfolios in whole or in part, as well as of individual Specimens. Upon these conditions are piled the many challenges to identifying and locating them through library catalogues and websites (as well as sales catalogues). We have reported on such constraints, for example, in our blogpost on More Discoveries for “Otto Ege Manuscript 61”. See also below.

That some success is possible engaging with this challenge derives in no small measure from paying close attention to the terms in which Ege himself described the items, whether in print or in handwritten notes upon the leaves or their mats. The attention can yield some results discoverable in roundabout, but effective, ways.

As always with researching materials dispersed in multiple collections, some of which have online information (sometimes including images of the materials), any results may have to depend upon the nature (and extent) of the information and metadata provided for the objects — and upon access to such materials and information.

Incunabula

Ege’s Contents List for the Incunabula (“Incunables“) in the Portfolio describes their Specimens in succinct terms. They concern printed books produced in the early age of printing in the West — that is, by conventional agreement, up to the year 1500. See, for example, surveys of the History of Printing and Incunables. All are the products of printing by moveable type, rather than, say, blockbooks, a genre which Ege’s Portfolio ignores.

Private Collection, Ege FBNC Contents List, Detail: Incunabula.

After the 6 specimen Manuscripts, the Incunabula are represented by 5 Specimens. All on paper, their texts occur in Latin, Italian, or German.

Ege listed them thus:

- 1472 Italy. Cicero, On Duty, printed at the de Spira Press (Venice)

- 1475 Italy. Laertius, Lives of the Philosophers, printed by Nicolas Jenson (Venice)

- 1480 Italy. Voragine, The Golden Legend, printed by Antonio de Strata (Venice)

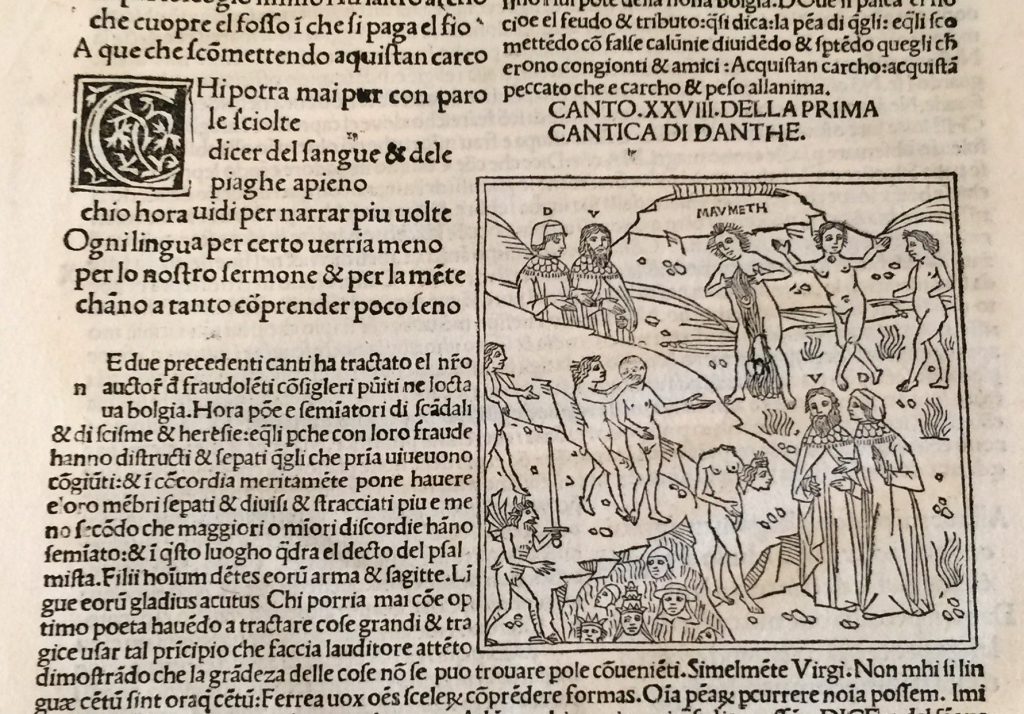

- 1491 Italy. Dante, Divine Comedy, printed by Petrus de Plasio (Venice)

- 1493 Germany. Hartmann Schedel, Nuremberg Chronicle, printed by Anton Koberger (Nurenberg)

That is, according to the numbering assigned to these publications in the Incunabula Short Title Catalogue (ISTC), they are:

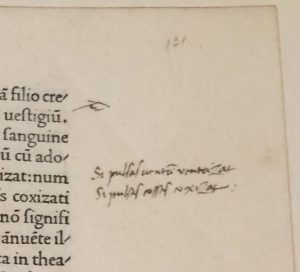

- 1472 Italy. Cicero, On Duty, printed by Johann and Wendelin of Speyer / Giovanni and Vindelino da Spira (Venice, 1472), folio 41

= ISTC ic00058000 - 1475 Italy. Laertius, Lives of the Philosophers (Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers), printed by Nicolas Jenson (Venice, 1475), folio 131 (with marginalia)

= ISTC id00022000 - 1480 Italy. Voragine, The Golden Legend, printed by Antonio da Strata (Venice, 1480)

= ISTC ij00095000 - 1491 Italy. Dante, Divine Comedy, printed by Petrus de Plaisio (Venice, 1491)

= ISTC id00033000 - 1493 Germany. Hartmann Schedel, Nuremburg Chronicle, printed by Anton Koberger (Nurenberg, 1493)

= ISTC is00309000

To these specimens from Incunabula, as well as others among the later Imprints, we might return in other posts.

Private Collection, Ege’s FBNC Portfolio, Dante Leaf, Verso, Detail. Reproduced by permission.

Manuscripts, One By One

First we consider the manuscript fragments.

Already our blogposts have begun to consider parts of Ege MS 51, as distributed in Ege’s Portfolios and by other means. The alternate means include the circulation of individual leaves on their own (sometimes in an Ege mat with his label), and the several portions of the ‘Residue’ (a binding included), after Ege’s extractions, now in the Otto Ege Collection at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University. See:

My first introduction to the manuscript came from Leaf 96, in a Private Collection. The leaf number appears at the bottom right of the recto, in pencil. Acquired by itself, without any Label, the leaf is firmly recognizable as one of Ege’s by its correspondence in format, layout, textual contents, style of script, material, and other features which establish its position formerly within Ege Manuscript 51.

Private Collection, Rectos of Single Leaves from Ege MSS 41 and 51, with guide. Photography Mildred Budny.

Some of the ‘Residue’ of Ege Manuscript 51, binding included, but with despoiled innards, has come into view in the Otto Ege Collection at the Beinecke Library.

The damaged binding of Volume II, viewed from the spine:

Beinecke Manuscript & Rare Book Library, Otto Ege Collection, Volume II of Ege Manuscript 51, Spine View.

A view of the interior of the volume, opened to show its gutted gutter between folios 9v/27r (following the removal of folios 10–26 between them) and the results of water or liquid damage at the top of the book. In the outer margin on the verso, accompanying the text, there stands a square-shaped diagram drawn in ink, with inscribed labels.

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, Ege MS 51, Volume II, opened at the gap between folios 9v/27r. Photography Mildred Budny.

Now we consider the manuscript leaves in the newly revealed set of Famous Books in Nine Centuries which came from a sale in Ohio and entered a Private Collection. With permission to show its images, we begin with the first Leaf in the set.

The Koran Leaf = Ege MS 53

In its mat, with its identifying label at lower left:

Koran 1 Ege MS 52 in Famous Books Portfolio in Mat

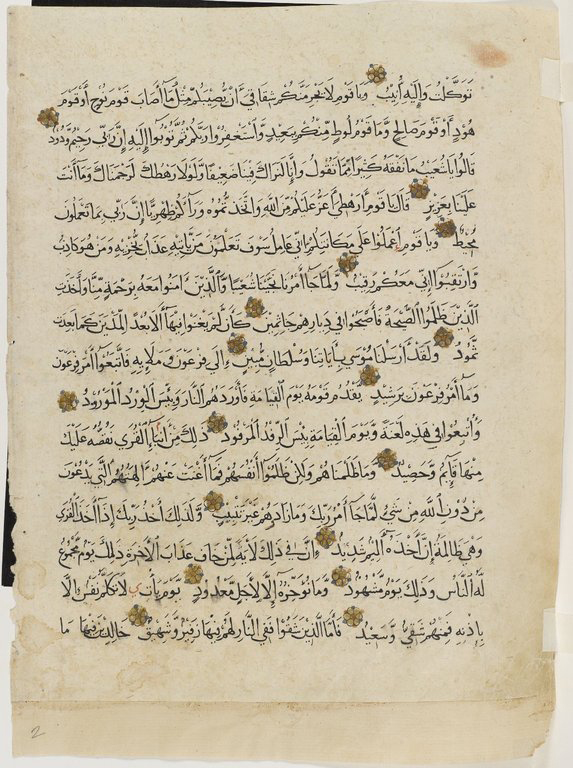

Closer up, behind the window of the mat, we can glimpse the full extent of the leaf, with trimmed or cropped margins which removed part of the script and other elements. Patched repairs at the bottom of the leaf employ 2 overlapping pieces of paper.

Private Collection, Koran Leaf in Ege’s Famous Books in Nine Centuries, Front of Leaf. Reproduced by permission.

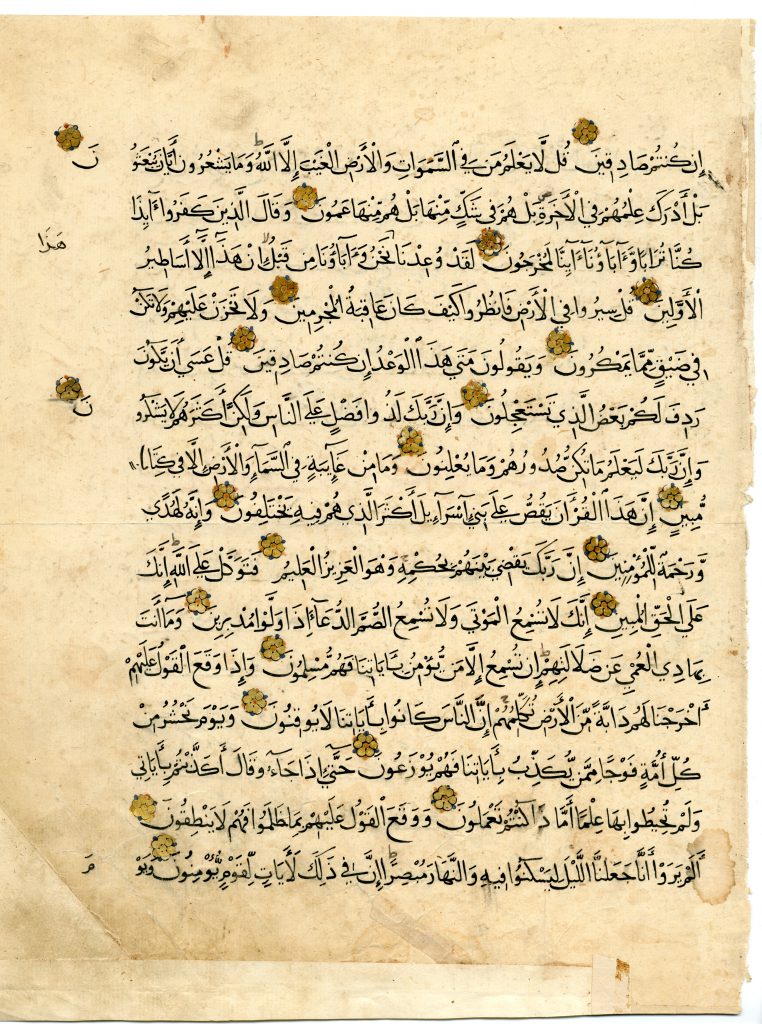

The other side of the leaf, lifted partway from the backing mat on the hinged gauze tapes characteristic of Ege’s mountings:

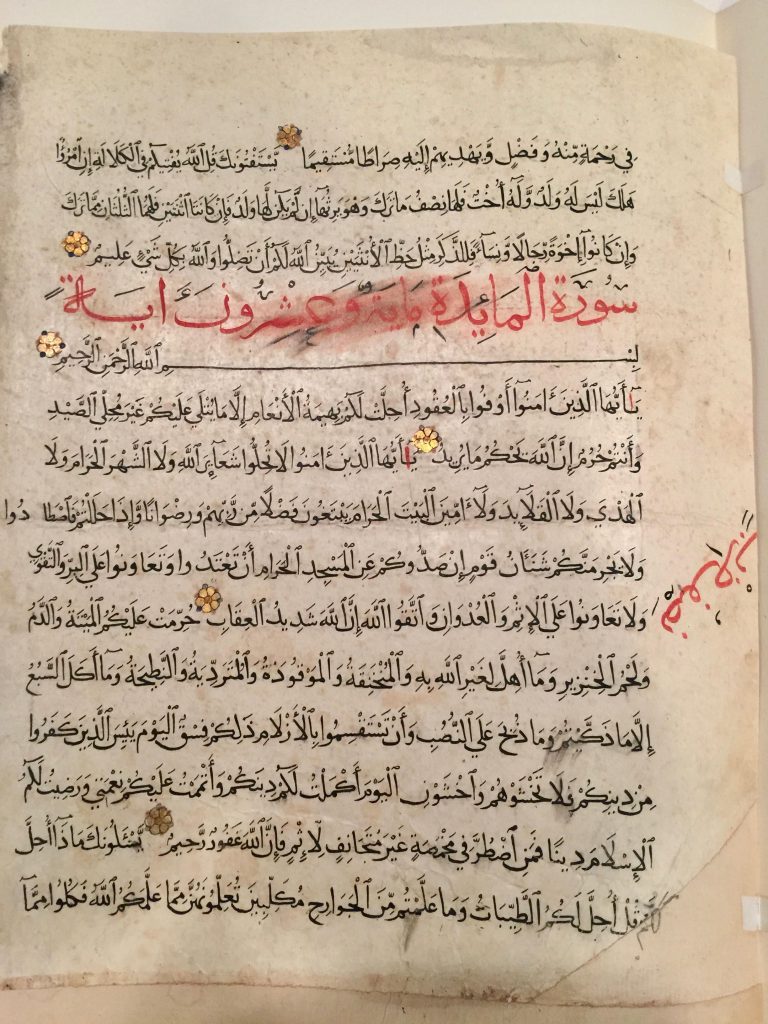

Private Collection, Koran Leaf in Ege’s Famous Books in Nine Centuries, Back of Leaf. Reproduced by permission.

Note that the leaf has a pasted repair, sub-triangular in shape, at the lower inner corner, remedying a lost portion. An added entry of script supplies the missing or covered elements on one side of the patch, pasted to the back of the leaf. Pasted to the front of the leaf, a longer strip of paper across the width of the leaf repairs or strengthens its undulating lower edge.

The Text

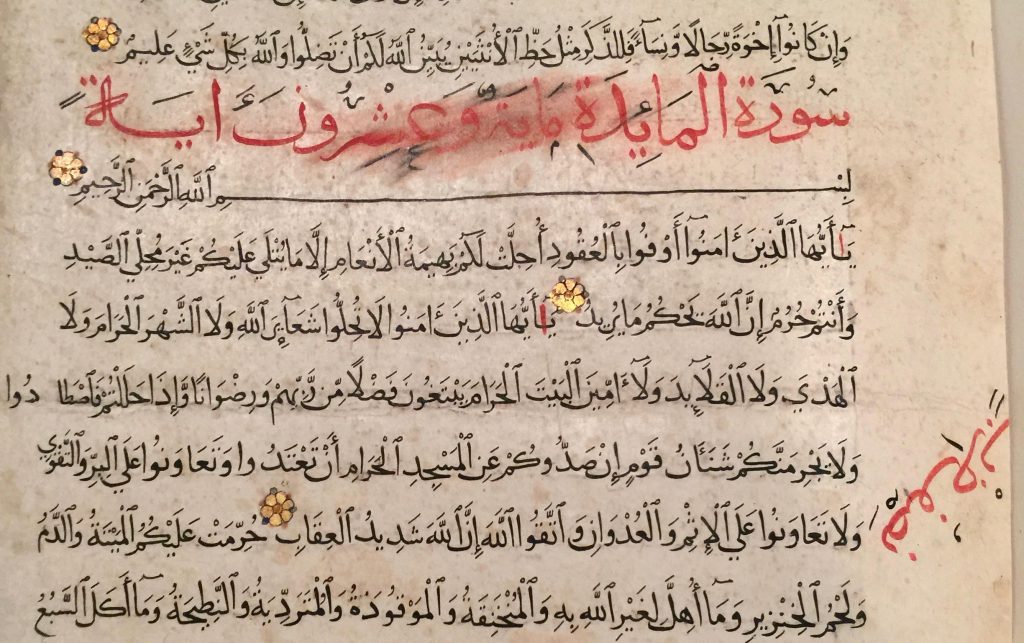

The text starts on the front, or recto, of the leaf. It begins within the middle of verse 162 (of 176 verses) of Surah ٱلنساء / An-Nisāʾ (“The Women”). On this Surah, Chapter 4 of the Quran, see, for example, An Nisa or An-Nisa. It considers issues relating to women, marriage, inheritance, orphans, rights, and more. The text here differs slightly from the online version which we found (for example, Quran; see also Sacred-texts), in that the words occur in a different order. Continuing through An-Nisa, the page ends in the middle of verse 174. The text continues on the other side of the leaf, on which Line 3 ends An-Nisa.

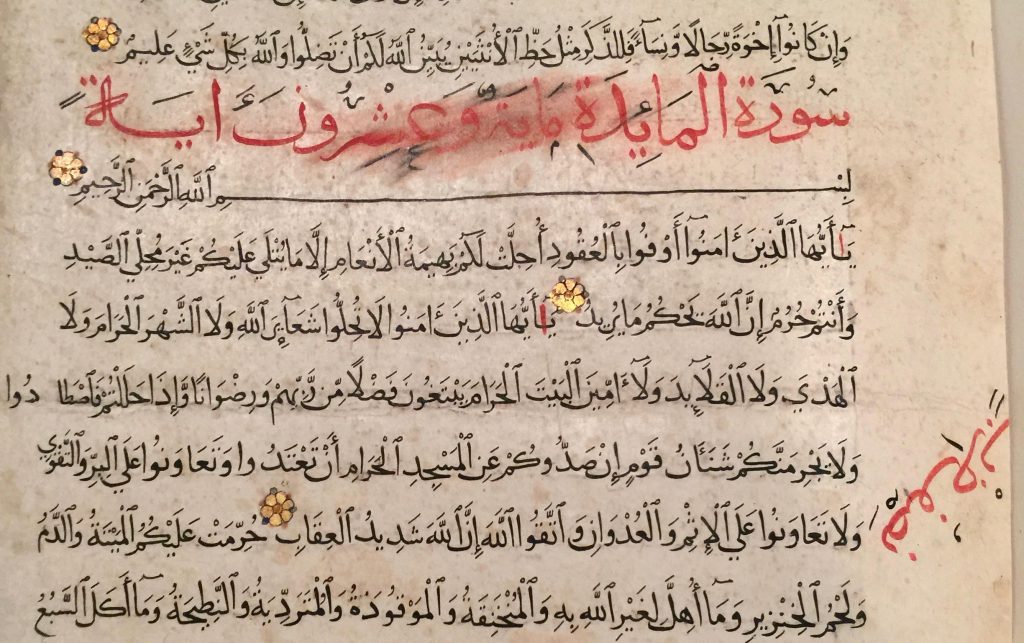

Next comes the rubricated title, spanning a full line, for Surah Al-Ma`idah (“The Table”, “The Table Spread”, or “The Table Spread with Food”), that is, Surah 5 which spans 120 verses. See, for example, the opening and bilingual text of this Surah in Sacred-texts.

With a broader nib than the main text, the title is written in a single line of red pigment, spread the full width of the column (line 4). Red dots above and below the characters provide the letter identifiers. Marks in black ink indicate the vowel- and length-marks for reading.

Private Collection, Koran Leaf in Ege’s Famous Books in Nine Centuries, Title for Surah 5. Reproduced by permission.

Spread across another full line, in the same ink and script of the main body of text, there follows the Basmala, the standard invocation

بِسْمِ ٱللَّٰهِ ٱلرَّحْمَٰنِ ٱلرَّحِيمِ) (bi-smi llāhi r-raḥmāni r-raḥīmi , “In the name of Allah the merciful . . . “).

This phrase leads to the Surah text, starting at verse 1 and ending within verse 4 at the bottom of the page. Thus, the span of text on the leaf extends from within Surah 4:163 to within 4:175 on the recto, and from thence to Surah 5:1–4 on the verso.

The polychrome verse-markers take the form of 6-petalled rosettes, usually raised above the baseline of script. The group of petals surround a circular center of red pigment. Smaller circular motifs, 6 in number, alternating in color (red and green?), nestle between, or emerge from, the outer tips of each pair of petals.

The addition of script at the lower right on the patch supplies the missing elements لَهُمۡۖ from the severed, covered, and repaired section at the beginning of the line of text.

Textual Divisions

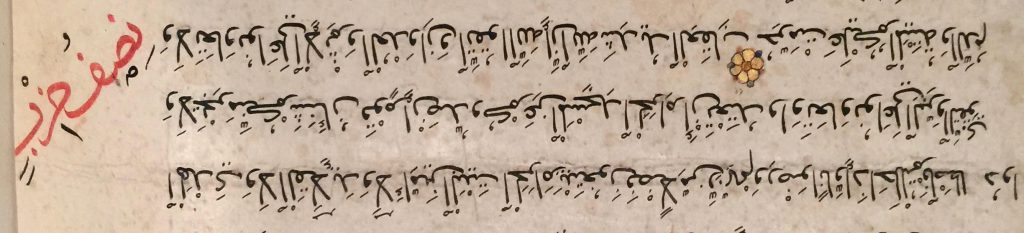

Upside-down in the right-hand margin below the title, at an angle leading toward (‘descending to’) line 10, and partly trimmed away at the edge of the leaf, there stands an inscription to indicate the opening of a section. Written in red, with letter-identifiers in red and vowel- and length-marks in black ink, it has a similar prominence and style as the title. It appears to be the work of the same scribe.

Private Collection, Koran Leaf in Ege’s Famous Books in Nine Centuries, Back of Leaf, Detail. Reproduced by permission.

Seen right-way up, that is, inverted with relation to the text, the marker reads thus:

Private Collection, Koran Leaf in Ege’s Famous Books in Nine Centuries, Back, lines 8-10, Inverted. Reproduced by permission.

The partly severed entry marks a division in the text. The first word is نصف (nsf), meaning ‘half’. There follow the letters z b (‘b’ certainly; ‘z’ is less certain), which might be read as زب — presumably a contraction of حزب (ḥizb’), meaning ‘group’. (Elsewhere the manuscript, as we can discover, preserves in full a comparable marking, so as to confirm this conjectured reading.)

The other side of the ‘new’ Leaf carries a second form of indicator for textual division. Entered solely in black ink apparently by a different hand than the scribe of the text, it forms a descending angle in the outer margin at the end of line 4. Upright with relation to the main text, it begins with the word ربع (rubuʿ, rubʿ, or rubue), “quarter”. In its full form, it designates: ربع حزب (‘quarter-hizb‘).

Private Collection, Koran Leaf in Ege’s Famous Books in Nine Centuries, Front, lines 1-6. Reproduced by permission.

The 2 marginal entries on recto and verso belongs to a graded system of inscriptions marking textual divisions in the Quran, intended to facilitate its recitation. Briefly, the elements of the system, as it has evolved over time and place, comprise a variety of units.

- Surah, or “Chapters”, 114 in number (of varying lengths), provided with titles

— divided into verses, or ayah ʾĀyāt (of varying numbers), on which see ayah - Juz’ ( جُزْءْ, ), or “Part”, 30 in number (of varying lengths)

- Hizb ( حزب , ḥizb), or “Group”, 60 in number (roughly equal lengths)

Further divisions also pertain. For example (see, among others, Rub el Hizb):

- A juzʼ is divided into ḥizbāni (“two Groups”)

- A ḥizb is one-half of a juz’

- Each ḥizb is subdivided into four quarters, making eight quarters per juzʼ

- Each of these is called Arba (ارباع) “quarter”, or alternately maqraʼ (“Reading”), making 240 Ahzab or ‘quarters’ in the full Quran.

Moreover, longer chapters among the surah might receive other forms of subdivisions for purposes of recitation, without breaking the flow of the topic.

- Ruku (رُكوع, Rukūʿ), “Passage” or “Stanza”, denoting a group of thematically related verses in the Quran, and amounting to 558 rukūʿs within it.

Each Hizb is subdivided into four equal parts, that is, a ‘quarter’ or Arba (ارباع). The three middle quarters of a ḥizb have these names:

- First quarter of Hizb: Rub ul Hizb (ربع الحزب)

- Second quarter of Hizb: Nisful Hizb (نصف الحزب)

- Third quarter of Hizb: Thalathatu (ثلاثة ارباع الحزب)

The ‘new’ leaf has diagonal entries in the margins marking both a ‘first’ and a ‘second’ quarter (without the ‘ul’). The second is inscribed in rubricated, polychrome form similar to the Surah title and of an equivalent prominence. The first appears less formal, inscribed only in ink and by a different, less polished, hand. One marker is upright; the other is upside-down in relation to the Quran text.

According to the site https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juz%27 , the first-quarter of Hizb 11 (spanning the text of Surahs 4:148 to 5:26) should occur at 4:163 (within An-nisah, as here). The first verse on the leaf stands within 4:163. Might we, perhaps, expect its marking (‘Hizb‘?) to stand at the bottom of the previous leaf? Now dislocated from this one, perhaps it survives in some other collection.

In sum

To sum up the contents of the leaf:

Recto: Surah 4:163 to 4:175 (in An-Nisa, “The Women”)

Verso: Surah 4:175 to 4:176 (end of the Surah)

Rubric title for 5 Al-Ma`idah (“The Table Spread”) and the Bismallah

Surah 5:1 to 5:4 (halfway through the verse)

Margins:

Quarter-hizb near 4:166

Half-hizb near 5:3

From the Wikipedia site ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juz’), the divisions of hizb 11 are:

4:148–4:162 (ḥizb)

4:163–4:176 (quarter-ḥizb)

5:1–5:11 (half-ḥizb)

5:12–5:26 (three-quarter-ḥizb)

The annotations on the leaf do not line up exactly with the WebSite ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juz%27), if they are to mark the start of the section specified there. However, the interval between them is consistent with the length of the passages.

The pattern(s) of textual division-markers applied to this Koran manuscript dismembered by Ege for his Portfolios may show its intentions for use in its original shape, its signs of use and adaptation, and perhaps also its position within the ‘evolution’ over time and place of practices of such markings — both upside-down and upright — for purposes of recitation.

Recto and Verso

Right-to-left Language Books. Diagram by Takasugi Shinji (Own Work), via Wikimedia Commons.

It is possible, perhaps probable, that the prominent smear across the middle section of the rubricated line of script of the title led Otto Ege to chose to place this side of the leaf on the hidden side within the mat, with the unsmeared page facing outward through the window. The placement turned the original recto of the Arabic leaf into a Western recto, reversing its location within the original manuscript, properly to be read from right to left on the page and from front to back on its leaf.

Note that the terms ‘recto’ and ‘verso might mean different things, depending on the reading direction and the point of approach to the ‘start’ of the leaf. See, for example, Recto and Verso (“Front” and “Back”). Here we use ‘recto’ to indicate the first side of the leaf intended to be read in the course of the text, and ‘verso’ to indicate the second side in the direction of reading.

Ege’s positioning of the selected leaves from whatever book within their windowed mats customarily masks from view the full contours of specimen. As a result, it is often impossible to tell from the windowed front of a framed Specimen alone whether the Leaf comes from an original recto or verso. In some exceptions, as with some specimens in the ‘new’ set, the framed view shows a folio-number, with one number to the leaf, or 2-sided folio. Sometimes, instead, the number in view can pertain instead to a page-number, applying one number to each side of a leaf, or page. Unless the observer is familiar with the edition in question, or has access to a view of the other side of the leaf, it could be unclear whether the number seen within the mat pertains to one folio (both recto and verso), or to only one side (either recto or verso).

A couple of cases in the ‘new’ Portfolio exemplify the range.

First, a manuscript, showing folio-number “35” (twice) within the mat (in ink at top right and in pencil at bottom right):

Private Collection, Ege’s Famous Books in Nine Centuries, Aristotle Leaf within Mat. Reproduced by permission.

(As it happens, the presence of these folio-numbers can significantly aid the virtual reconstruction of the manuscript in question, and contribute to the study of its history. As shown in this blogpost: More Leaves from ‘Otto Ege Manuscript 51’.)

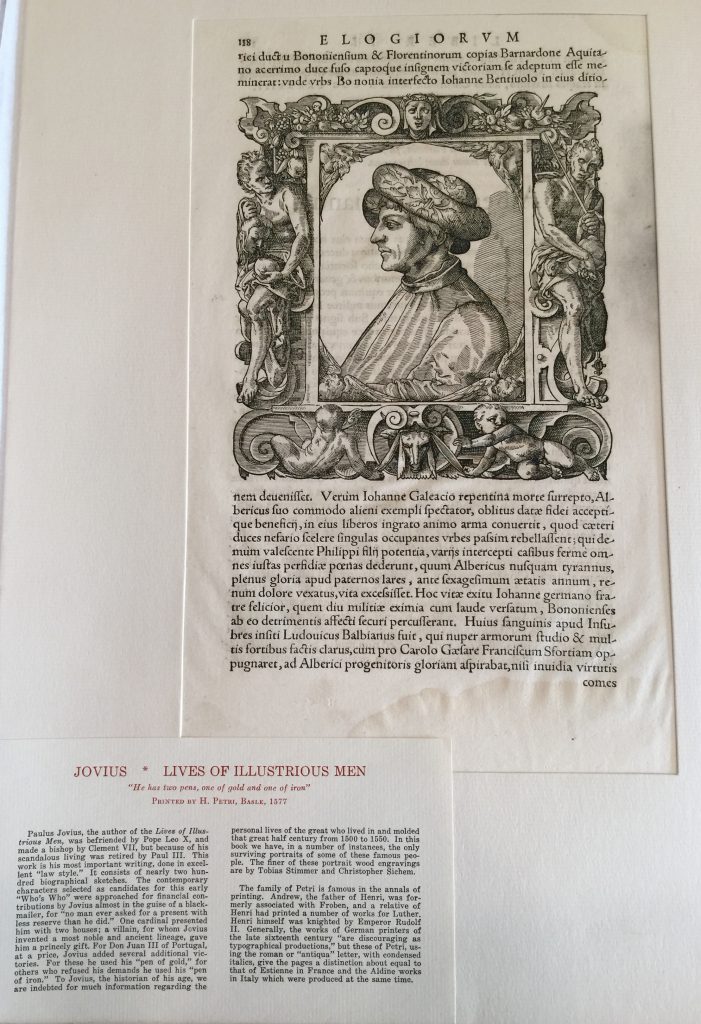

Second, a printed specimen, showing page “118” at the front (with page “117” turned to the back):

Private Collection, Ege’s Portfolio of ‘Famous Books in Nine Centuries’, Jovius, ‘Illustrious Men’ (1577) Specimen Front in mat. Reproduced by Permission.

The practice of selecting, and visually cropping, a seemingly privileged side of a leaf — and not necessarily its original ‘recto’ — governs the presentation of Ege’s Specimens, regardless of whether they come from Western or other writing systems.

The Leaf and Its Manuscript

Private Collection, Ege FBNC Koran Leaf Label.

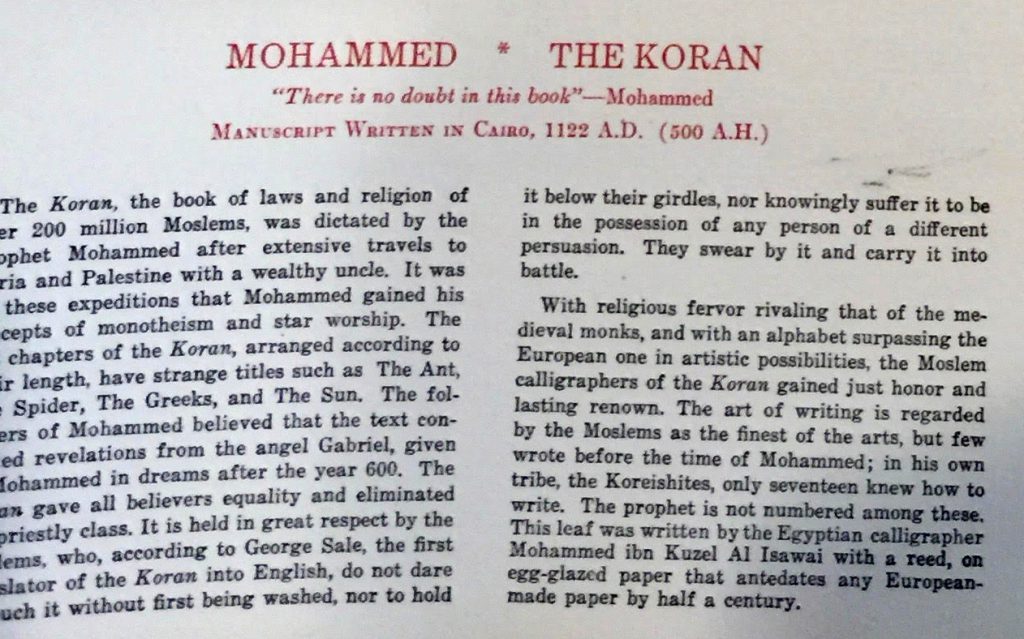

On this manuscript, and the individual specimen, Ege declared in his Label:

The Koran, the book of laws and religion of over 200 million Moslems, was dictated by the prophet Mohammed after extensive travels to Syria and Palestine with a wealthy uncle. It was on these expeditions that Mohammed gained his concepts of monotheism and star worship. The 114 chapters of the Koran, arranged according to their length, have strange titles such as The Ant, The Spider, The Greeks, and The Sun. The followers of Mohammed believed that the text contained revelations from the angel Gabriel, given to Mohammed in dreams after the year 600 [CE]. The Koran gave all believers equality and eliminated the priestly class. It is held in great respect by Moslems, who, according to George Sale, the first translator of the Koran into English, do not dare to touch it without first being washed, nor to hold it below their girdles, nor knowingly suffer it to be in the possession of any person of a different persuasion. They swear by it and carry it into battle.

With religious fervor rivaling that on the medieval monks, and with an alphabet surpassing the European one in artistic possibilities, the Moslem calligraphers of the Koran gained just honor and lasting renown. The art of writing is regarded by the Moslems as the finest of the arts, but few wrote before the time of Mohammed; in his own tribe, the Koreishites [Qyarysh], only seventeen knew how to write. The prophet is not numbered among these. This leaf was written by the Egyptian calligrapher Mohammed ibn Kuzel Al Isawai with a reed, on egg-glazed paper that antedates any European-made paper by half a century. [Emphasis added.]

Ege’s entry for the Leaf in his Contents List identifies the work as

Mohammed, Koran Manuscript on paper, written by the calligrapher Mohammed ibn Kuzel Al Iswai. Small illuminated rosettes.

Private Collection, Ege FBNC, Contents List, Manuscripts 1 & 2.

The Manuscript and Its Date

The date, place of production, and name of the scribe must derive from a scribal colophon which the manuscript contained, but which Ege’s dismemberment dislocated from the other leaves. Those pieces of information had to circulate with Ege’s notes and his labels, without our ability by direct observation to challenge or to affirm the claims of the colophon, its manner of execution, and other means.

Alongside Ege’s attribution, Scott Gwara’s Handlist (p. 137) provides a different assessment:

Ege Description: “Manuscript written in Egypt (Cairo), 1122 A. D. (500 A. H.)”.

Gwara Description: “MS on paper. Egypt, dated 1122 but Mamluk dynasty, s. xv”

The span of the Mamluk Sultanate extended from 1250–1517. At the purported date of the manuscript (or its exemplar), Egypt belonged under the control of the Western caliphate and the Fatimid dynasty (969–1174), followed by the Ayyubids. Many studies and reference works examine manuscript production for these periods. See the suggestions for Further Reading at the end of this post.

When I asked our Associate, David Sorenson, what view he might have about the date-range of the “new” leaf and its manuscript, he replied:

Re. Quran — Boyd Mackus had one at K[alama]zoo [i. e. one year or other at the Annual International Congress on Medieval Studies; see its Archive]. It looked to me like a typical Mamluq leaf, 14th–15th century, as Scott says. The easy way is to check the paper; if it has any chain lines it’s got to be after 1250 or so. [Emphasis added.] The writing style looks later, anyway. You can look through Blair to see examples. 1100 or so would be an earlier type (late Fatimid) with a quite different script style.

The reference here to “Blair” indicates Sheila S. Blair, Islamic Calligraphy (Cairo, 2006). Suggestions for further references and links to manuscript collections online appear at the end of this post.

Recently, in working to create a Gallery dedicated to Watermarks and the History of Paper, the Research Group on Manuscript Evidence has published the updated and downloadable version of David’s illustrated conference paper on “Paper-Moulds and Paper Traditions: What Mould-Patterns in Near Eastern and Indian Paper Suggest Regarding Origins of Local Papermaking” (2020). (See Paper Moulds and Paper Traditions and the downloadable paper.) It includes observations about the importation and manufacture of paper in Egypt, or with Egyptian provenance, from about the ninth and tenth centuries (CE) onward (see especially pp. 5–7, with specimens).

Ege’s Portfolio of Oriental Leaves perhaps has a different Label for specimens from this Koran manuscript than its Label for Famous Books in Nine Centuries (as shown above). So far, I have not yet seen an example of either the Contents List or “explanatory caption” for the Oriental Leaves, apart from quotations of information which accompanied the Leaf in some form. The title of that Portfolio describes itself thus:

Fifteen Oriental Manuscript Leaves of Six Centuries:

Twelve of the Middle East, Two of Russia, and One of Tibet

from the Collection of and with Notes Prepared by Otto F. Ege

The online images of both sides of the Koran Leaf in the Oriental Leaves Portfolio at the Brooklyn Museum are accompanied by a caption quoting “Printed material” in these terms (presumably Ege’s?):

“Koran by Mohammed: Egypt, Cairo, early 12th century 1122 A. D.; Arabic Mohammedan text, Arabic script, Nashki style.” (Koran Leaf)

On the style of script, see, for example Naskh (Script).

Leaves in Other Sets

Some other leaves from this manuscript appear online. Under current conditions of bibliographical research, with access to many libraries closed or limited, exploring Ege’s Portfolios and their dispersal mainly requires resorting to online resources and the books and other materials which I have to hand, or can find. Among them are stores of photographs from visits to multiple collections on the track of research on Ege’s Portfolios and other quests.

Some leaves from the Quran manuscript belong to one or other set of Ege’s Portfolio of Famous Books in Nine Centuries (as at the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh). Some belong to a set of Ege’s Portfolio of Oriental Leaves (as at the Brooklyn Museum in New York ). Some appear to be separate leaves. The appearance, or apparent condition, of separate leaves might in some cases (many?) reflect their institution’s label, the removal of the individual leaves from the set and the mats, and/or the distribution into different divisions of the larger collection or into different collections altogether. As a result, for various reasons, the labelling or cataloguing by the collection or institution can mask, bury in ‘fine print’, or outright ignore the connection with Ege, or with one or other of his Portfolios.

Needless to say, such factors can impede or interfere with research to recognize different leaves from the manuscript now in different locations.

My consultation and photography, with permission, of the set (Number 20) now at the Princeton University Library several years ago provides the opportunity to re-examine it virtually offline, and to identify its place within the former manuscript.

- Princeton, Princeton University Library, Firestone Library, Special Collections, Oversize 2008-007E;

The recto, beginning midway through Surah 13:40, Ar-Ra’d (“The Thunder”), carries the rubricated title for Surah 14, Ibrahim (“Abraham”); the verso carries the rubricated upside-down marker ‘half-hizb’ in the outer margin opposite 14:10, and closes within 14:22.

A few examples of leaves as seen in print or online:

- New York, Brooklyn Museum, Ege’s Portfolio of Oriental Leaves, Koran Leaf

Recto

Brooklyn Museum, Libraries and Archives, Z209 Eg7, Koran Leaf, Recto. No known copyright restrictions.

The recto starts with verse 74 within Surah 11, “Hud“. Note that the rubricated entry in the outer margin (partly trimmed, like the one on the ‘new’ leaf) marking the textual division of a “Half-Hisb“, or “Half-Group”, stands upright with relation to the text (unlike the orientation on the ‘new’ leaf). Note also the modern paper repair across the bottom of the leaf.

Verso

Brooklyn Museum, Libraries and Archives, Z209 Eg7, Koran Leaf, Verso. No known copyright restrictions.

- Private Collection, Koran Leaf within a set of the Famous Books Portfolio, illustrated (one side only, cropped without revealing whether recto or verso) in Disbound and Dispersed: The Leaf Book Considered (2005), page 82.

Its red title opens Surah 13: Ar-Ra’d (“The Thunder”).

- Location Unknown, FBNC Set 28, sold at Christie’s on 21 September 2020 as Lot 10.

Provenance: (1) Otto F Ege (1888-1951). (2) Bruce Ferrini. (3) Alexander E. Vida, by descent.

Images of both sides of the Quran leaf (gallery-13 and gallery-14) show its span of text. It contains part of Ar-Ra’d (“The Thunder”), Surah 13, starting in 13:15, with the page-break at mid 13:29, and ending mid 13:40. The hizb marker is roughly correct for Ar-Ra’d 13:19.

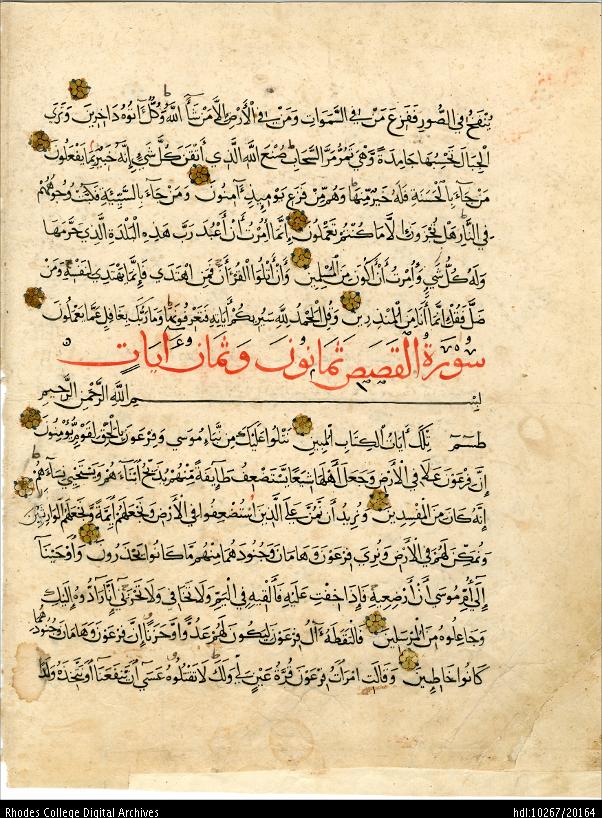

- Memphis, Tennessee, Rhodes College, Archives and Special Collections, Hanson Collection, Ege Box 3, Leaf 1

(identifier: http://hdl.handle.net/10267/20164) – a leaf which, it is said, arrived within Ege’s mat for it.

The red title, on the verso, opens Surah 28: Al-Qasas (The Stories”).

Note the pair of paper patches at the lower edge, with a subtriangular patch at the outer margin and a longer horizontal patch across the bottom, like the ‘new’ leaf.

Recto

Rhodes College Archives and Special Collections, Memphis, TN. Hanson Collection 3, Koran Leaf, original recto, via http://hdl.handle.net/10267/20164.

Verso

Rhodes College Archives and Special Collections, Memphis, TN. Hanson Collection 3, Koran Leaf, original verso, via http://hdl.handle.net/10267/20164.

- Queens, NY, Saint John’s University, Archives & Special Collections, FBNC, verso only; otherwise [access restricted]

The text on this page extends from Az-Zumar (“The Groups”) at the start of Surah 39:63 ‘لَهُ مَقَالِيدُ السَّمَاوَاتِ’ to the end 39:75, followed in the last line by the title for Ghafir (“The Forgiver”) ‘غَافِر‘ (Surah 40).

The rubricated inscription for the textual division of a “Half-Hizb” stands upside-down in the outer margin (see above).

- Raleigh, North Carolina Museum of Art, Near Eastern Department, Leaf from a Koran, showing only the recto and citing the date 1122.

(This leaf and its Portfolio set of Famous Books in Nine Centuries is not recorded in Gwara’s Handlist.)

The rubricated inscription for the textual division of a “Half-Hizb” in the outer margin (see above) remains in full, uncropped; at an angle, it stands upright with relation to the text.

- Columbia, South Carolina, University of South Carolina, Ernest F. Hollings Special Collections Library, Early Ms. 128 (the gift of Scott Gwara)

— with no image, but with the information that “the word ḥizb is written upside down on the margin of the verso”, indicating a textual division.

In this latter case, the online catalogue entry not only refrains from identifying the span of the text, but also leaves uncertain whether the Leaf belongs to, or came from, one or other of Ege’s Portfolios, or circulated in some other way instead. It states:

“[The leaf] Relates to a Qur’an leaves [sic] included in Otto F. Ege’s Fifteen original [Oriental] manuscript leaves of six centuries and Original leaves from famous books. This leaf was attributed to Mohammed ibn Kuzel Al Isawai by Otto F. Ege. Ege dated the ms. ca. 1122.”

More research, and more available information, would reveal further details about the structure of the manuscript as a whole, its context, its scribal attribution, and other features.

The Scribe and the Date

With accompanying labels or notes, the variously circulated leaves have mostly traveled to their current locations with a report of the name of the calligrapher as “Mohammed ibn Kuzel Al Iswai”, the date of “1122 [CE]”, and the place of origin as Egypt, and particularly Cairo. This knowledge would have travelled with the leaf, whether in some note, label, or contents list by Ege. Sometimes, alas, the specific form of transmission is not reported, or is only inconsistently or ambiguously mentioned, by the institution in its cataloguing or the accompanying metadata.

Sometimes the information about the leaf may have appeared in, or also in, handwriting — as seems to be the case with the leaf at the Brooklyn Museum of Art (to judge by part of the online catalogue description). It was not uncommon for Ege to have inscribed such information in pencil at the bottom of the mat and/or on one side of a detached leaf itself, as the leaves from a book were separated and dispersed variously on their own or in company with severed leaves from other books or manuscripts, Portfolios and other means included. Examples are illustrated in other blogposts about Ege’s manuscript fragments. (See our Contents List.)

For the Koran manuscript, presumably we must assume that Ege derived the name of the calligrapher and the exact date from a scribal colophon within the manuscript — if not from some extra-textual information which came to him with the book, say on an endleaf or the binding, or in some other form from the seller.

As stated in his Label for the Nine Centuries Portfolio (seen above):

This leaf was written by the Egyptian calligrapher Mohammed ibn Kuzel Al Isawai with a reed, on egg-glazed paper that antedates any European-made paper by half a century.

So far, a scribal colophon has not come into view on any leaf as yet recognized as part of the same book. Occasionally for some of Ege’s manuscripts, a colophon surfaces somewhere in a dispersed leaf, as the case with 2 other manuscripts deployed as specimens in the Famous Books Portfolios:

- the Aristotle manuscript (Ege Manuscript 51) and

- the Livy manuscript (Ege Manuscript 52).

The latter case survives at Rhodes College, with the colophon reporting the date as 12 September 1456; it is shown here. Multiple colophons in the former are described and illustrated in More Parts of ‘Otto Ege Manuscript 51’ .

One wonders what other information a colophon in Arabic might have conveyed, not only in terms of its textual contents, but also in terms of its script, its location within the book, and other material evidence.

As for a different date between the wording of a colophon and the apparent date of the manuscript, it is not unknown in manuscript production, both Eastern and Western, that the colophon of an earlier scribe, with its earlier date, could be copied unchanged in the process of transcribing the exemplar.

Presumably, Ege took the colophon at face value, without recognizing other features which could signify a much later date for the script, paper, textual markings, and other features.

Coda: Reed or Pen

It is uncertain whence Ege derived his belief that “This leaf” (namely, whichever one accompanied his Label) “was written . . . with a reed”. The use of a reed pen, especially for papyri (and cuneiform), is well attested. The images available for view from the Koran manuscript show rapid gradations in widths of strokes more characteristic of quill pens.

Perhaps Ege drew his inference from his belief that the manuscript represented an early, pre-European form — replete with egg-glaze as a finish.

*****

Further Reading

On the production of Quran manuscripts over time and place, from the 7th century (CE) onward, their scripts and calligraphic practices, and their structure, punctuation, and embellishment, see, for example:

For the Metropolitan Museum of Art:

- Maryam Ekhtiar and Julia Cohen, Early Qur’ans (8th–Early 13th Century)“The introduction of paper into the region [with the importation from China to the Middle East] allowed for the production of far more Qur’ans than had previously been possible.”

For the British Library:

- Colin F. Baker, Calligraphy of the Qur’an.

- The Qur’anic Manuscripts.

— with a list of links to “The Qur’anic Manuscripts In Museums, Institutes, Libraries & Collections”

Further references

Colin Baker, Qur’an Manuscripts: Calligraphy, Illumination, Design (London: The British Library, 2007)

Sheila S. Blair, Islamic Calligraphy (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2006)

Francois Deroche. The Abbasid Tradition: Qur’ans of the 8th to 10th centuries A.D. (London: Nour Foundation in association with Azimuth Editions and Oxford University Press, 1992)

———, Islamic Codicology: An Introduction to the Study of Manuscripts in Arabic Script. (London: Al-Furqān Islamic Heritage Foundation, 2005)

Mohammad Gharipour and Irvin Cemil Schick, eds. Calligraphy and Architecture in the Muslim World (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013)

David Roxburgh, Writing the Word of God: Calligraphy and the Qur’an (Houston: Museum of Fine Arts, 2007)

Yasin Safadi, The Qur’an: Catalogue of an Exhibition of Qur’an Manuscripts at the British Library (London: World of Islam Publishing Co. Ltd for the British Library, 1976)

*****

We thank the owner of the “new” Portfolio of Famous Books in Nine Centuries for permitting us to examine and publish this find. We likewise thank the owners of other materials from Otto Ege’s collection for allowing access to the sources and related evidence. We give thanks also to our Associates and others for advice over the years about Ege’s manuscripts and their distribution, and now to Leslie French and David Sorenson for advice specifically about the Koran/Qur’an manuscript.

Further posts might present other leaves from this Portfolio and their relatives, as well as other discoveries for Ege Manuscripts.

Private Collection, Koran Leaf in Ege’s Famous Books in Nine Centuries, Back of Leaf, Detail. Reproduced by permission.

Do you know of more leaves from this manuscript? Of other sets of the Portfolios of Famous Books (in Nine and/or Eight Centuries) or Oriental Books? Do you have suggestions for the date and origin of this manuscript? Other works by the named scribe?

Please let us know. Please leave your comments here, Contact Us, and/or visit our Facebook Page. We look forward to hearing from you.

*****