A New Leaf from ‘Otto Ege Manuscript 214’?

April 13, 2018 in Anniversary, Manuscript Studies

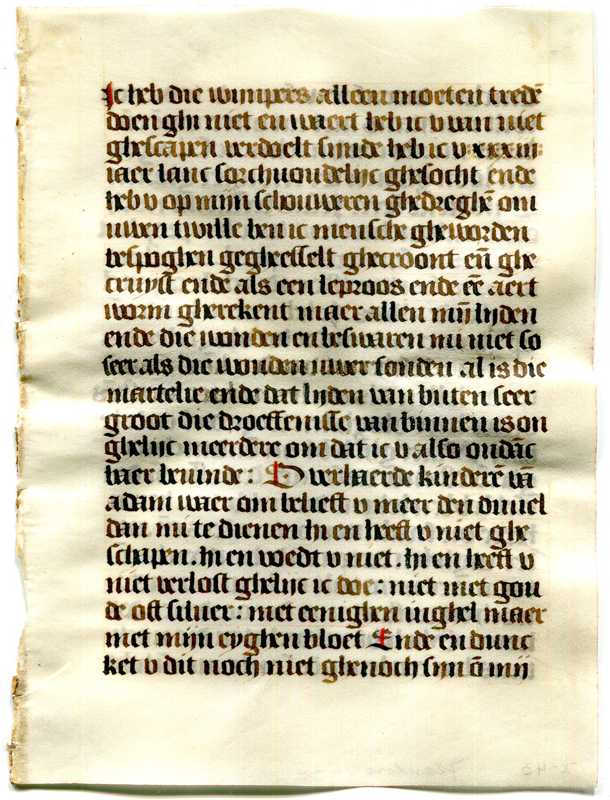

Part of a 22-Line Prayerbook in Dutch

From the Collection of Otto F. Ege?

Single leaf from a small-format Prayerbook

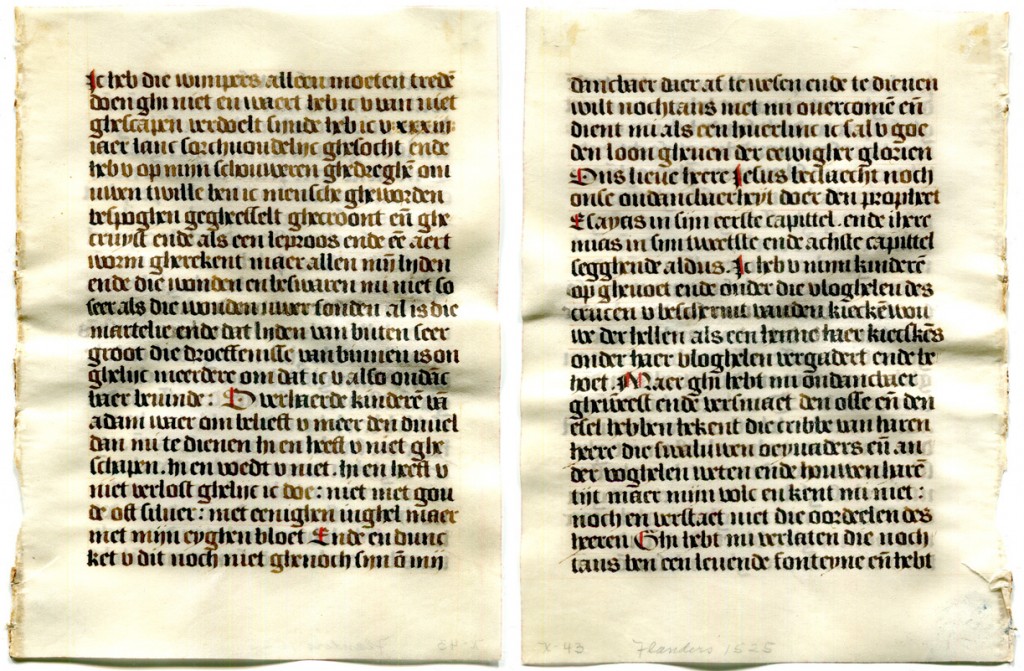

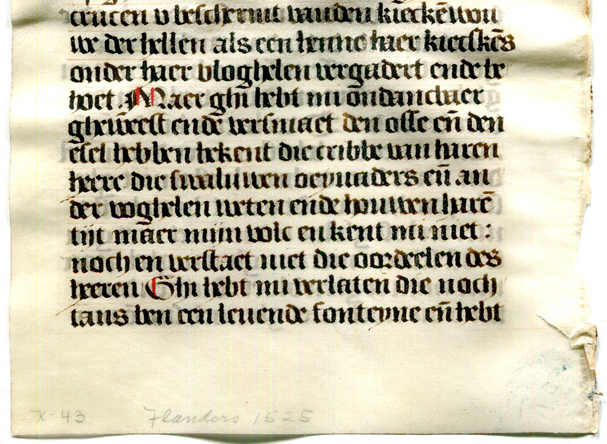

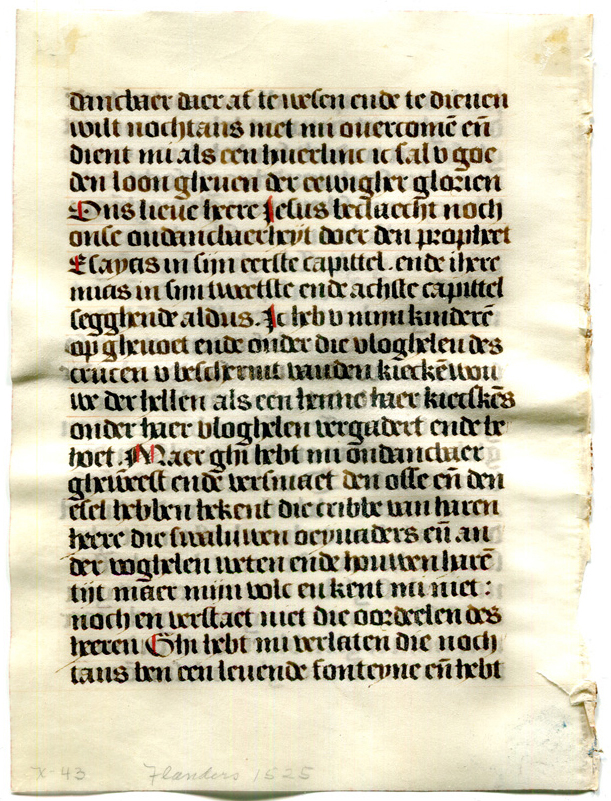

Circa 166 × 177 mm <written area circa 128 × 82 mm>

Single column of 22 lines in Gothic Bookhand, with embellishments in red pigment

Pencil inscription ‘X . 43 Flanders 1525’ at the bottom of the recto

Perhaps formerly part of Ege Manuscript 214 (Gwara, Handlist 214)

Flanders, circa 1330

[Published on 13 April 2018, now with updates with thanks to Peter Kidd.]

Continuing our series on Manuscript Studies, Mildred Budny (see Her Page) adds new evidence to her earlier reports about some medieval manuscripts dispersed by Otto F. Ege (1888–1951). See our Contents List.

This time we showcase a leaf recently acquired for a private collection.

Its online seller did not cite provenance nor identify the text and any source manuscript. The new owner, dedicated to the acquisition of manuscript fragments (conditions permitting), having acquired several Ege manuscript fragments already, opined that this leaf would have come from “Otto Ege Manuscript 214”. Could be.

So, what is that little-known “Ege Manuscript 214”, and what are its surviving fragments? How might we find out enough from the scrappy sources about those scraps to figure out whether or not the “source manuscript” — AKA the former manuscript of this specific remnant — is that book from which the New Leaf came?

Wait and See. Read On, Dear Reader, Read On.

The New Leaf, in a Nutshell

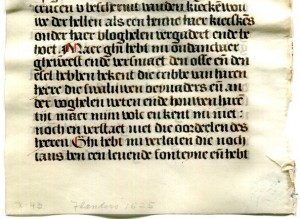

Taking it from both sides, left to right, here are the original recto (front) of the leaf and the original verso. The seller’s inscription in pencil at the bottom of one side treats it as the recto, or front, although the textual sequence and the codicological evidence of the sewing patterns in the inner margin demonstrates that the original position was different.

Let us say that the placement of the seller’s inscription not only demonstrates ignorance about, or indifference to, the progression of text on the leaf and the textual orientation upon the remnant. It also could register the preferential treatment in the presentation of the leaf to the seller and any potential buyer. I go so far (because of other known observed cases) to say that the position of the seller’s inscription most probably could — knowing Otto Ege’s practices of presentation for single leaves (reported in our earlier blogposts, listed above) — provide evidence that the distribution of the leaf somehow favored the original verso as the ‘preferred’ side.

*****

Considering the Context and Challenge of “Otto Ege Manuscripts”

To state this new case concisely. A few words about the complicated context imposed by “Ege Manuscripts” and other dismembered and dispersed manuscripts.

Continuing our series on Manuscript Studies, here we focus on another leaf which may have been dispersed through the efforts of Otto F. Ege (1888–1951) in assembling and distributing specimen leaves extracted from original one-of-a-kind manuscript books.

Previously we considered the issues of Ege’s Lost and Foundlings, and then, in stages, reported the discoveries of a New Leaf (or more) from several different “Otto Ege Manuscripts”. Our blogposts reported the discoveries by the convenient arabic numbers assigned in current scholarship to Ege’s dispersed manuscripts, insofar as they are known and recognized.

Different sizes, different genres, different texts, same predicament.

Cut up and cut loose. Cut it out! The practice of cutting up manuscripts, that is. Hard work trying to trace and track down the traces.

*****

The New Leaf

A closer look may be in order.

Verso Forward

The seller’s description in pencil in the lower margin of one side of the leaf approaches that side as if it should be facing forward. Facing upward in whatever stack or mount or mat in which the individual leaf arrived, anyway.

However, the course of the text, the alignment of the column of text on the leaf, and the orientation of its former gutter or stitching line within the former volume, as assembled and bound, demonstrates that this remnant turned its first page backward, and its second page front, in its journey from its original manuscript to its new home.

Recto Forward

Within the book, this side faced front instead. The thin parchment permits the pencil inscription on the verso to show through.

‘Otto Ege Manuscript 214’

In Scott Gwara’s Handlist of Manuscripts Collected or Sold by Otto F. Ege (2013), that former manuscript, with some traceable remnants, is his Number 214 (Appendix X, pages 177–178). There he cites a few traceable remnants from it and their catalogue appearances. These references provide points of departure and directions for consideration.

I offer a few observations from a first look at resources available at hand, guided by earlier experiences in working with Ege manuscript fragments of several types. Don’t know yet if this stray New Leaf in Dutch comes from that manuscript, but let’s explore. Regardless of the outcome of the identification (or not), the process of assessment itself can be instructive.

BTW. I don’t yet know the answer to this identification (or not), so let us join this exploration together.

Clues and Cues

This “New Leaf” requires looking at a known dispersed Ege manuscript which did not figure among Ege’s selections for the various Portfolios. My researches so far on Ege materials have concentrated on several of those different Portfolios, and in numerous sets from each of those issued Portfolios. My blogposts tell their tales.

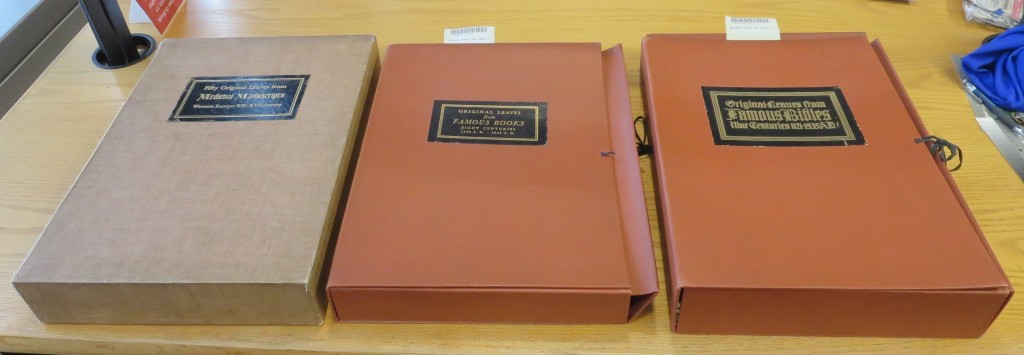

The cases involve Portfolios assembling selections of specimens extracted variously 1) from 50 miscellaneous medieval manuscripts, 2) from Bibles across the centuries and in various languages, in manuscript or in print, and 3) from “Famous Books” (ditto). See, for example,

More Discoveries for “Otto Ege Manuscript 41” (among the “Fifty Medieval Manuscripts”)

Ege Manuscript 51 (among the “Famous Books”, issued in 2 versions of this Portfolio, respectively in Eight or Nine Centuries, and with variations infuriatingly unannounced within each version)

Ege Manuscript 61 (among the Bibles, ditto)

Three Ege Portfolios. “Fifty Original Leaves from Medieval Manuscripts”, “Original Leaves from Famous Books” (Series A in “Eight Centuries”), and “Original Leaves from Famous Bibles” (Series B in “Nine Centuries”). From the Collection of The Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County. Photograph by Mildred Budny.

On Its Own

Not this time. Can’t turn to such ensembles, and their partly-known complicated forms of diverse and dispersed transmission, which the work of scholarship, cataloguing, selling, reselling, and other forms of record by various agents over decades and in recent years can illuminate, especially in combination. (See our blogposts.)

Gotta start from scratch (ish). The challenge of this leaf, considering whether it belongs to an identifiable Ege manuscript or not, requires some different forms of resources and approaches, apart from the growing base of knowledge which focuses upon one or another and more manuscripts dispersed in Ege’s Portfolios. Let’s see what might emerge.

Gwara’s Handlist Citations for “Ege Manuscript 214”

Gwara’s brief list (2013) of sources and resources for his Handlist 214 cites one auction catalogue and 3 collections.

1. 1985 Sotheby’s Sale Catalogue of some Remnants, including left-overs not quite fully dismembered

This sale catalogue presents many manuscript materials — fragments, mostly, in the form of clumps of manuscripts having been dismembered to greater or lesser extents. Another, spectacular, sad case is Otto Ege Manuscript 14″. These mutilated remnants belonged to a sale by Otto Ege’s descendants getting rid of clumps of materials.

(By the way, some similar “clumps” of manuscripts in complicated, messy states of dismemberment still awaiting dispersal have emerged in the Otto Ege Collection presented to the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Collection at Yale University by Otto Ege’s descendants. One eye-opening case is described first-hand More Discoveries for Otto Ege Manuscript 51 and Updates for Some Otto Ege Manuscripts.)

I am grateful for help in finding a copy of this sale catalogue. It took a while, but we persevere. The catalogue entry is informative and instructive.

- Sotheby’s, Western Manuscripts and Miniatures (London, Tuesday 26th November 1985), lot 88.The entry reports:

55 leaves, some detached, others still sewn to old bands with pieces of calf spine, 22 lines, written in dark brown ink by 2 scribes in a late gothic liturgical hand, rubrics in red, capitals touched in red, many initials in red or blue, SIX LARGE ILLUMINATED INITIALS (3- to 4-line) in delicate rustic designs in liquid gold on coloured grounds, fine condition (166mm by 120mm).

There is more. Having the benefit of examining all 55 leaves offered for sale (among whatever original number the manuscript may have formerly contained), the cataloger assessed the nature of the remnant, insofar as its contents permitted.

Then the cataloguer observes:

Comprising biblical readings and prayers, including three ascribed to the Commisasrius “meester Godschalc rosemond van Eundhoven, Doctoer in der godeyt” [that is, “Eindhoven in South Holland, about 45 miles south east of Utrecht“], there are offers of indulgences ascribed to popes Alexander VI (1482–1503), Julius III (1503–1513) and Leo X (1513–1521).

Portrait by Raphael Sanzio (circa 1518) of Pope Leo X and his First Cousins, Cardinals Giulio de’ Medici (later Pope Clement VII) and Luigi de’ Rossi. Uffizi gallery, Florence. Via Creative Commons.

Those popes’ grants of indulgence (with specified amounts of remission for sins depending upon specific amounts of specified restitution) and their own known dates of papal reign or tenure establish — at least for those 55 leaves on offer in the Sotheby’s sale, never mind the others known or not – a terminus post quem (“date only after which” for the production or completion of the volume) of the reign of Pope Leo X (born Giovanni di Lorenzo de’ Medici). Therefore 1513 and counting.

However, the absence (insofar as we know) of the relevant leaves and testimonies mean that we can have little knowlege of whether those various indulgences belong to the original manuscript, to some additions or other, to some rearranged and replaced leaves, or to Who-Knows-What. Plus we’re not sure if all the leaves of the manuscript were produced at one time (more-or-less) or if multiple times of production, revision, and recreation pertained to the preparation of this manuscript. Yikes.

You think I am kidding? For example, some close studies by Kate Rudy about Dutch and Latin prayerbooks (among other books) in the late medieval period vigorously document and illustrate such variable practices. See also our blogpost about some relevant fragments in Canada.

*****

On a sort-of optimistic note, on this renewed quest, recently I find encouragement, and solidarity, with observations in the Beyond Words exhibition catalogue entry for a group of leaves from another dismembered Ege Manuscript (“Ege Manuscript 79”) — an Italian Book of Hours of circa 1480 — now in the School of Theology Library of Boston University (Folder STh MS 80) = Beyond Words, Number 233 (page 293). As that catalogue entry by 3 authors — the experts William P. Stoneman, Laura Nuvolini, and Peter Kidd — states succinctly:

This is an example of a dismembered manuscript where the discovery of each new leaf has the potential to radically change what we know about the original volume. They allow us to continue the process of reconstructing the original texts, quire-structures, and decorative program.

The quest continues. We are in good company.

2. The Remnants of “Ege Manuscript 214” in Identified Collections

The present whereabouts of these leaves are not fully known. Presumably they were dispersed by the buyer, sooner or later, directly or indirectly, piecemeal. Some of the traced remnants may be attributable to this dispersal point. Some remnants perhaps or presumably entered their voyage earlier, through Ege’s own efforts. Here are the remnants which Gwara cites for his Ege Handlist 214.

214.1. Boston, Massachusetts, Boston University, School of Theology Library, MS Leaf 7.

Judith Oliver, Manuscripts Sacred and Secular from the collections of the Endowment for Biblical Research and Boston University (1985), number 84 (page 48), without illustration of the leaf or identification of the text. So far as I have been able to discover, that leaf is not yet presented for observation online. For now, we note its existence, and await further exploration to learn more about its characteristics.

[Update: Peter Kidd has sent me photographs of both recto and verso. This leaf is the work of the same scribe as “our” leaf.]

214.2. Columbia, South Carolina, University of South Carolina, Hollings Library, Early MS 130.

Can’t find it online under that number 130. Presumably this one instead?

University of South Carolina Early MS 133

The Notes for this item online [excerpted] identify it thus:

Prayer Book, 1530

A late Dutch prayerbook once owned by the American dealer and collector Otto F. Ege (d. 1951), ca. 1530.

Language Dutch

Origin The Netherlands

Layout Single folio on vellum: 166 x 117 (written area 125 x 80 mm). Single column, 22 lines per page.

Decoration One-line initials alternating red and blue, else capitals highlighted by a single red penstroke. Extant historiated initials are painted in the style of Simon Bening. [emphasis mine].

Note that Early MS 133 has no historiated intials. Only text, with those red and blue highlights. The entry gives no reference as to where to find those “extant historiated initials”, so we have to resort to further exploration, guesswork, and luck.

214.3. Pittsburg, California, Philip G. Shoemaker Collection, MS 61 with “2 miniatures”.

Gwara, Handlist of Manuscripts Collected or Sold by Otto F. Ege (2013), figure 97 (page 229), in a quarter-page black-and-white illustrating the cropped text column which contains the “Historiated Initial of the Nativity in the Style of Simon Bening, for a Dutch Prayerbook, Bruges, ca. 1530″ (caption), with manuscript fragment identified on page 213 in the “List of Illustrations”.

Ah! Here is one of those initials, available for viewing, contemplation, and comparison as a starting point potentially for virtually reassembling parts of the dismembered Dutch volume.

More Leaves Identified, With Thanks to Peter Kidd

[Update:]

In an email communication of 15 July 2019 about his discoveries for various Ege manuscripts, including this one, Peter Kidd reported that, for Ege Manuscript 214, that “There are leaves with miniatures at the National Gallery of Art in D.C., the Art Museum in Indianapolis, and (recently acquired) at Oberlin” College, along with that “unilluminated leaf at BU”, that is, Boston University, School of Theology Library (see above). From the photographs which he sent, it is possible to identify their contents.

- Washington, D. C., National Gallery of Art

Recto: Part-page illustrations of the Annunciation to the Shepherds (Luke 2) and the Flight to Egypt (Matthew 2)

Verso: Part-page illustration of the Adoration of the Magi (Matthew 2) - Indianapolis, Indiana, Indianapolis Art Museum

Recto: Part-page illustration of the Evangelist John in scribal pose, accompanied by his symbol the eagle (Luke 1) - Oberlin, Ohio, Oberlin College Libraries

Part-page illustatrion (recto or verso?) of the Nativity (Luke 2)

We look forward to learning more.

Date-Range for Dismemberment and Dispersal

Meanwhile, Ege’s sale in the late 1940s of one leaf from this prayerbook, among at least 27 fragments to the Endownment for Biblical Research (Zion Research Foundation), establishes a date-range for the dispersal of parts of the prayerbook. So says Gwara, Handlist of Manuscripts Collected or Sold by Otto F. Ege (2013), footnote 152 on page 153.

Both that footnote and its text cites as the evidence the presence of the Boston leaf from “Ege Manuscript 214” within the catalogue by Judith Oliver of manuscript materials in the libraries of both the Endowment of Biblical Research and Boston Library (see above). However, the specimen from “Ege Manuscript 214″in Oliver’s catalogue belongs to a different collection: Boston University, School of Theological Library, ST 84. I haven’t yet had the chance to investigate the source and date of acquisition by that collection, but it is on the list.

Worth saying that the Dutch manuscript dismembered by Ege does not appear to figure within the 1937 Census of selected manuscripts in Otto Ege’s collection. That record is Seymour de Ricci, with the assistance of W.J. Wilson, Census of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts in the United States, Volume II (1937), page 1937, Item 4 in ‘The Library of Otto F. Ege, 188 South Compton Road, Cleveland, Ohio’.

Some dismembered Ege manuscripts within our view benefit from being identifiable, or perhaps identifiable with that 1937 Census . As with Ege Manuscript 61 and More Discoveries for “Otto Ege Manuscript 61” . Not this time.

The point is that we should, of course, look at any scraps of evidence, hints, or direction which might provide some clues about the lost leaves, Ege’s leaves included. As with some other former Ege manuscripts (see our blogposts, among other sources), finding — one way or another, through detective work and sometimes inspired serendipity — the sales catalogues of the volumes, before Ege got hold of them and took them to pieces, can reveal multitudes of information.

As spectacularly, for example, here: Ege Manuscript 14. And here: More Discoveries for “Otto Ege Manuscript 51”.

*****

The Style of Simon Bening

While we’re here. Were there available for observation miniatures ascertainable as part of this former manuscript, we might have clearer knowledge of the context. What if some leaves — not the solitary text leaves — have illustrations identifiable with one or another known artist? Cool!

Or not. Who knows?

Meanwhile, let’s go with what the scholarship (so far as I have discovered) has to say about Otto Ege Manuscript 214 and its artistry. The Sotheby’s Catalogue of 1985, viewing “SIX LARGE ILLUMINATED INITIALS” among the specimen of 33 leaves, names no artist. Scott Gwara, presumably viewing some of those very initials, twice provided an attribution to the “style of Simon Bening”.

Simon Bening (c. 1483 – 1561) was one of the most famous and celebrated painters of the 1500s.

Small-format Self-Portrait by Simon Bening, dated 1558. Tempera on Parchment. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image via metmuseum.org via Creative Commons.

A small-format self-portrait, executed in tempera on parchment and measuring circa 8.5 cm × 5.7 cm, survives in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Its inscription in Latin reads “Simon Bennik. Alexandri. [F]ilius Se Ipsu. Pi[n]gebat. Ano. Aetatis. 75. 1558.” (“Simon Bennik, the son of Alexander, painted this himself at the age of 75 in 1558”).

A prayerbook in Dutch and Latin illustrated by Simon Bening at an early stage in his career sold at Christies (6 July 2011, Sale 7932, lot 26). Examples of his manuscript paintings, demonstrating the meticulously detailed beauty of his work, are showcased at The J. Paul Getty Museum and in the Beyond Words exhibition at Boston and its online catalogue (number 117).

*****

Summing Up, For Now

We still don’t know if the New Leaf formerly belonged to Ege Manuscript 214. It is a working conjecture, pro tem, shall we say. More work awaits.

As always, we remain eager to discover the traces and connections for fragments of medieval manuscripts.

Looking forward to finding the former “home” of this leaf with its former manuscript, as we search for locating orphans to find a welcome within the virtual “Foundling Hospital for Manuscript Fragments” — as described in the post which began this blog on Manuscript Studies.

*****

Next stop? More discoveries, of course. Do you know of some? Please give your suggestions and Contact Us.

Update:

See now Some Leaves in Set 1 of “Ege’s FOL Portfolio”. More discoveries for Ege manuscripts keep turning up.

Follow our blog and see its Contents List.

*****