Manuscript Groupies

August 2, 2015 in Manuscript Studies, Photographic Exhibition

Preview:

An Illustrated Handlist of a Group of

Medieval and Early Modern

Manuscripts, Documents, and Printed Materials

Conservation, Photography, Research, and Descriptions

by Mildred Budny

As we unveil more of the research results for an extended study of a group of medieval and early modern manuscripts, documents, and printed materials, its Illustrated Handlist deserves an Introduction. Here, instead, is a Preview or Trailer.

[Update: And here is the Illustrated Handlist.]

Jest for Fun

Details of the materials in the Handlist, their conservation, and cumulative research results are reported, in stages, on other parts of this website (for example here), as well as in an illustrated Album, now in preparation for print. Here is a light-hearted Preview, in the form of:

A Brief Introduction,

Partly Playful but Also Earnest,

Illustrations Included

Photography by Mildred Budny

The Best Side

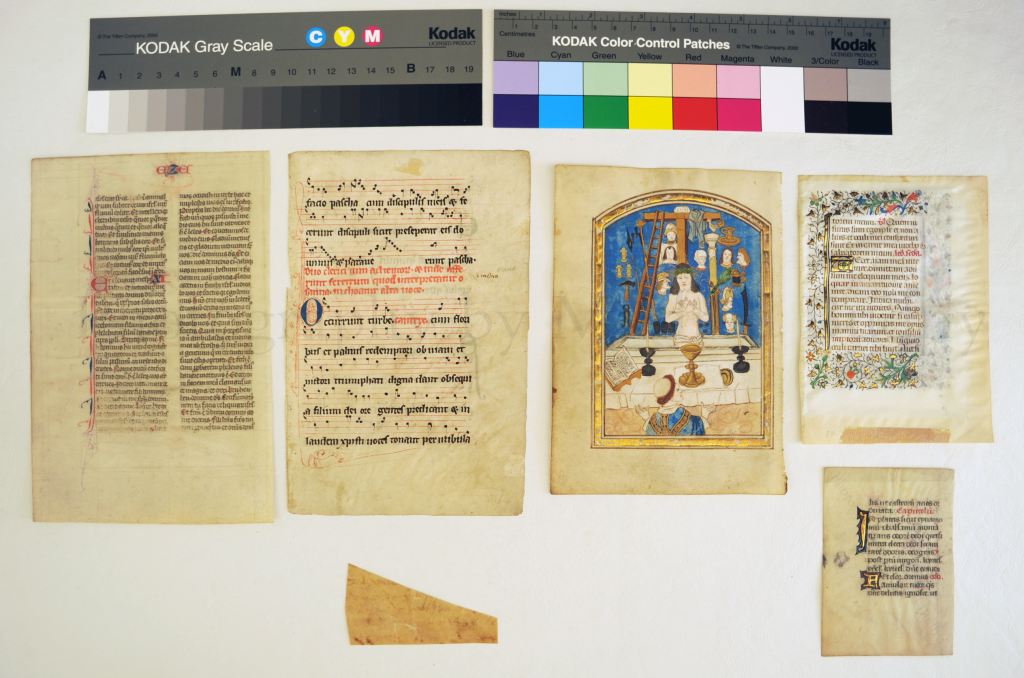

To set the scene, a pair of informal Group Portraits shows the Best Sides of some hand-written leaves in the Handlist.

(P.S. Each Side counts as a Best Side in our book . . . )

These specimens — AKA ‘Models’ for the Portraits — come from several different parts of the Handlist. Our Models here belong among Parts I and II of the Handlist, along with the other ‘Single Leaves’ and ‘Documents’ — in these cases all on vellum or parchment and mostly in Latin.

Some of them have richer decoration than others, depending upon their own resources, their talents, their training, their agents, their stylists, their make-up, the set-designers, the Director (in this context, that would be me), and the parts they have been assigned, or have decided, to play. Play is the operative word today.

Take Two

And so here we have Group Portraits I & II (with Lady), unretouched. Don’t we love seeing the Stars when they don’t have extra makeup, bodyguards, etc., and can show their real, natural selves?

For my part, I like both these Portraits. For one thing, they show different Sides. For another, they both look fabulous, just the way they are. That’s my view(s), anyway.

Which would you prefer?

Seeing the Bright

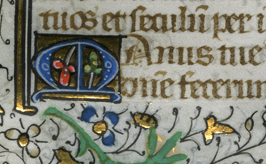

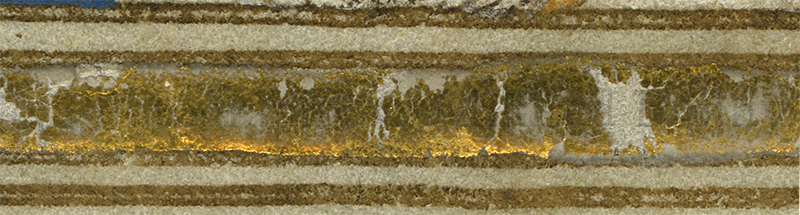

As for asking for their autographs, well, these Models already show their signature handwriting. Some elements are even in gold. Real gold, at that.

By the way, as a photographer (See Here Too), I observe that the gold leaf worn, for real, by three of our Models gleams especially effectively in these informal Portraits. Did you know that gold is diabolically difficult to photograph well on manuscripts? No kidding. No matter if you didn’t know that already, now you do.

Happily, the gold shows brightly in these snapshots, better even than in some more formal settings. Didn’t plan it. It just happened. A bonus! Remember what I said about their Good Sides? Er, no, I mean, their Best Sides?

When it comes to photographing touchy, sensitive, demanding Subjects (As If! Who’s the Subject, as in Servant, here?), the Golden Oldies can be extremely demanding. It feels special when, without elaborate Special Effects, they can be allowed to reveal their unique inner light. Now that takes Talent Scouting.

Roll Credits

To give credit where credit is due, I will readily name names. In each version of the Group Portrait, here are, from left to right, in Rows 1 and 2 (upper and lower):

- Handlist 7. From the Book of Ezekiel in a ‘Pocket Bible’ made in France

(part of the dismembered ‘Otto Ege Manuscript 61’)

- Handlist 4. From a Processional for Singing Nuns on Palm Sunday

(part of the dismembered ‘Otto Ege Manuscript 8’, also known as the Wilton Processional)

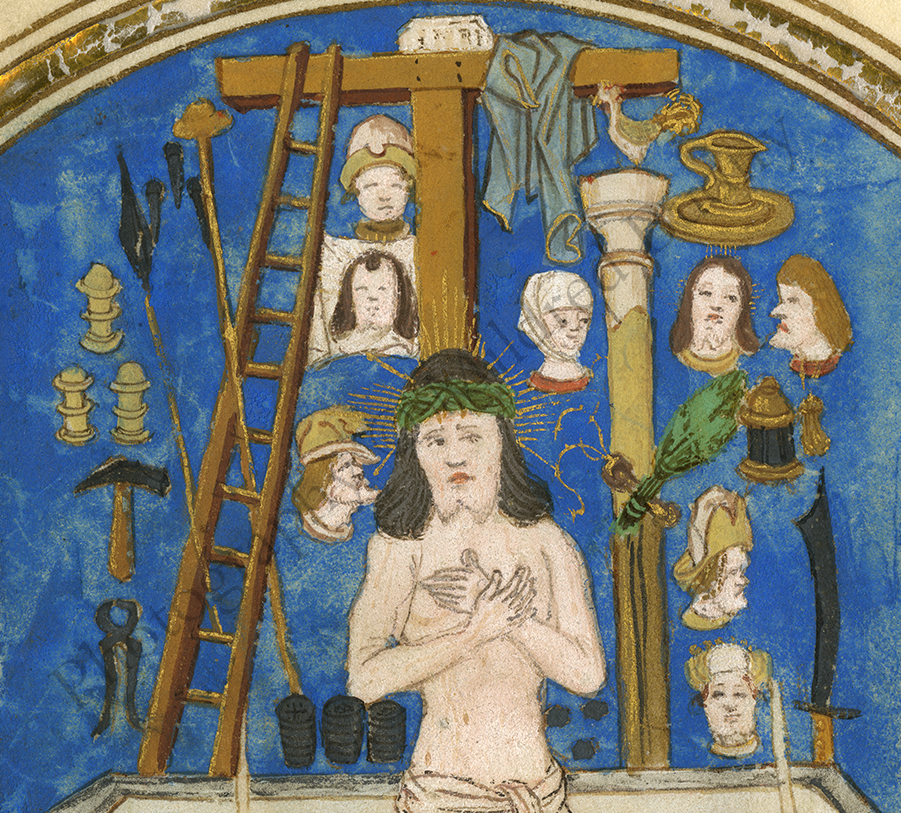

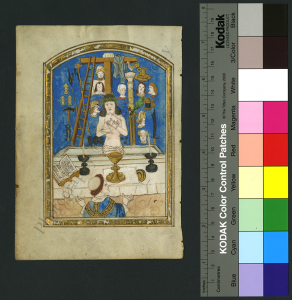

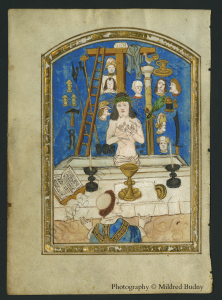

- Handlist 13. From a Prayerbook, the Gregory Mass Revealed

- Handlist 12. From the Office of the Dead in a small-format Book of Hours

- Handlist 22. The ‘Scrap’ (Also Known As a Scrap of Information, and

- Handlist 11. From the Hours of the Virgin in a Tiny Book of Hours.

Their relative sizes are clear at a glance, don’t you think?

As they line up, it is as if they take their bows and acknowledge our applause. After all, it took centuries to get their acts together! And they look really good for their ages.

We should be so lucky. (We live in hope.)

Back to Front

You may wonder that, in each Group Portrait, some leaves show their recto (‘front’), while others show their verso (‘back’), seemingly inconsistently.

As in: Verso/Recto/Verso/Recto/Recto/Verso in Take 1, and the reverse in Take 2.

Well, to let you in on the secret, when the time came for their Group Portrait — it was an exceptional Photo Op, which, shall we say, required clearing with their Press-Agents and within my own schedule — they jostled for pride of place, like any or every celebrity or hopeful. It seemed helpful, anyway energy-conserving (for some, or one, of us at least), to allow them to choose their positions, while I worked on the lighting.

This opportunity came at an early stage in the processes of photography, conservation, and research (in varying order, sometimes as the interlinked stages of examination, consultation, photography, and research entered into cycles of immersion, reflection, revision, and renewal), and before more of the items arrived. At that first stage, at the Photo Op, I had to recognize, not at all unwillingly, although a bit warily, that I had returned to photography of original manuscript materials after all, and after many things had rapidly changed, the world of photography included.

This return happened unexpectedly, and fortunately, after a gap of some years since the completion of the collaborative research project during which the Research Group on Manuscript Evidence was born, and the completion of its photographic work — some of which is showcased in the Illustrated Catalogue (1997), other publications, and other photographic exhibitions. With this invigorating renewal, I began to experiment with different approaches to manuscript photography, both analogue (as before) and digital (as now, in addition to analogue), with different views of the artefacts, with different forms of backgrounds and lighting, and with a new sense of exploration.

Exploration for its own sake, and for what it might offer for manuscript studies. With limited resources, true. (Life is short.)

But also with resourcefulness, dedication, perseverance, curiosity — and, yes, a sense of fun.

Back to the Future

Some of the results appear on exhibition, in print, and on screen in various ways. For example, Handlist 13 (Row 1), with its haunting image of the visionary Mass of Gregory the Great, is revealed in detail in a report, and it also features as the Star, Spokesman, and Poster Person (‘Poster Poster’?) representing principles and practices for photographic reproduction in our newly revised Style Manifesto.

Back on that set, during the Photo Op, without assistants to set the equipment, to soothe and distract the Models, to order pizza for them, to contend with their agents, to redirect the many requests for autographs, to arrange the bouquets, to hold back the paparazzi, and to book the tables for the post-shoot festivities, I had the pleasure of completing a first Test Shoot, in Takes 1 and 2, with narry a tantrum nor publicity agent in sight. A fantastic, auspicious start.

These Models were the Best! (No offense to the others!) Great Cast. Assigning their parts, or places, in the Handlist came later, as its script came into shape. Likewise, discovering their identities mostly came later, as my and others’ research work yielded more discoveries — as with the ‘Stage Names’ for the original volumes from which some of the dispersed fragments came, as with the ‘Otto Ege Manuscripts’ (on which see, for example, our 2016 Symposium, its Report, and its Illustrated Program Booklet).

If these Models were in print rather than manuscript, I might say that they were Type Cast, but that distinction belongs to some of the other Items in the Handlist.

Hug Shots

Years later, coming upon these snap-shots from the Photo Shoot, I wondered why I hadn’t taken more formal Portraits of the whole Group, that is, with others in the Handlist included. This while I had been taking such care to photograph each one in various views — as you can see, for example, in the reports about them in turn, on their own terms. (As in the revealing personal interview with the Gregory Leaf.)

The look back and into the future, at this stage of shaping the Handlist, allows for a moment of wistfulness, while welcoming those quick, provisional, snapshots (‘Polaroids’ in an even earlier age). Wistfulness, not regret. It is possible to be clear.

You see, now I see that perhaps these quick snaps can suffice to show the happy occasion of a gathering in recognition. Happy, we can say, it marks the resumption of detailed study of manuscript materials in the flesh, and also the celebration of companions gathered as ‘foundlings’ from among many ‘waifs and strays’ of medieval and early modern written materials ‘abducted’ from their original homes (books, documents, libraries, collections, locations) in Western Europe (not forgetting the British Isles), brought one way or another across the ocean to the United States, and welcomed into a new form of ‘foster home’ — whether, say, as a mobile or a ‘forever’ home.

Perhaps it is not really a mystery, although it remains a wonder. Every artist/actor/writer/manuscript worth his/her/its salt/sugar/weight-in-gold needs an audience. Nice when we can meet and greet, don’t you agree?

Lost-and-Foundling Hospitality

You can see that I continue to reflect on the fates of Lost and Foundlings among dispersed bits and pieces of written materials from earlier centuries, and to consider the possibilities of a Foundling Hospital of sorts, where we might welcome them, directly or indirectly, tangibly or virtually, and together find some companionable nourishment in embarking on our picnics with the past.

And now, next, let me introduce more of them, and their rescued companions, to you. Watch this space!

As the posts emerge, they join the Contents List for this blog on Manuscript Studies. Arranged by subjects or categories, rather than in the chronological sequence of publication, the List allows you to select your choices as from a Menu. Even possible is Dessert First!

*****