A Solitary Leaf, Detached

[Published on 7 April 2015, with updates]

Mildred Budny (see Her Page) reflects on a medieval manuscript leaf and its clues as a detached artifact. This post is one of the first in our blog on Manuscript Studies, for which there is now a Contents List.

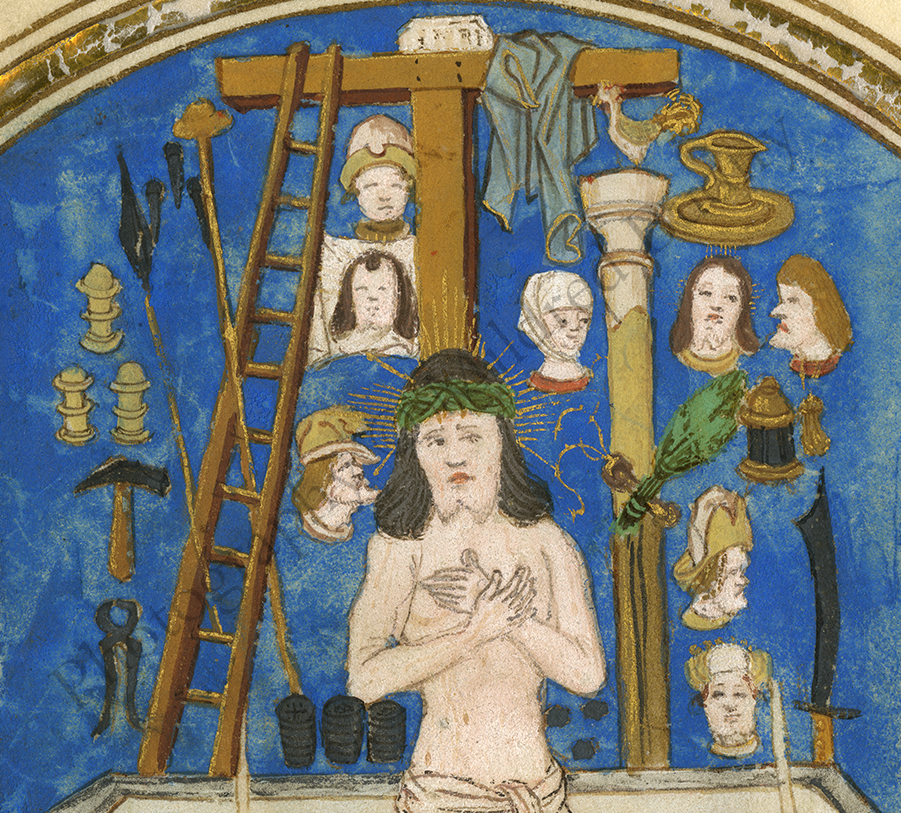

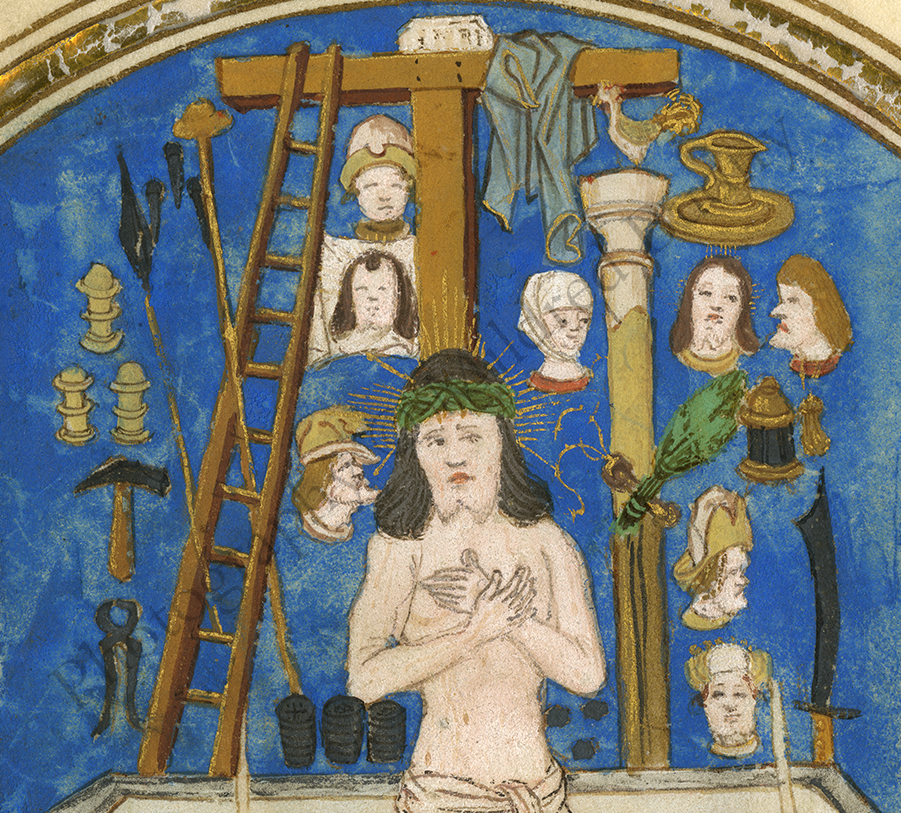

Christ’s Head, with Crown of Thorns

Veronica’s Veil

On the occasion of Holy Week, Good Friday, and Easter (Western and Orthodox) 2015, we post a new set of photographs of a detached leaf from a 15th-century prayerbook of some kind, as yet unidentified. Perhaps other parts of the book survive elsewhere.

The Image

The Mass of Saint Gregory

The small-format vellum leaf carries a full-page, framed illustration of the visionary Mass of Saint Gregory the Great (pope from 590 to 604). It represents a scene derived from an early account of his life and transmitted through later sources.

Here, the part-length upright figure of Christ, surrounded by many of the Instruments of His Passion as well as the disembodied heads of Tormenters, Traitors, and Others involved in those processes, arises from the open top of a sarcophagus behind a draped altar, which stretches the full width of the scene, as He appears to the tonsured and richly vested celebrant of the Mass. Seen from the back, turning his head toward the right, and lacking a halo, the part-length celebrant, who understandably raises both hands in wonder, might represent not only Gregory himself but also any metropolitan (or above) entitled to wear the pallium over his chasuble. With such cues, the image appears to stand, and to resonate, within, across, and outside time. The niche-like frame, with straight sides and a curved top, encloses the votive image with a rimmed gold band.

Both the details of the subject and the style of the skillful illustration point to a place of production probably in Flanders or Northern France in the early fifteenth century. The subject of Gregory’s Mass enjoyed wide popularity in the late Middle Ages, especially at this time, with depictions in various media (including manuscripts) encouraging meditation upon Christ’s Passion and its implications. Surveys of the transmission of the subject and suggested reading lists for further information appear freely online for example in German, French, and English, dedicated to somewhat different audiences and interests as well as languages — much as the subject itself could do in its medieval and early modern spheres.

An example of an illustration fit for a king, likewise with a bright blue background, painted circa 1500 in Tours, France, by the expert artist Jean Poyer, precedes the Seven Prayers of Saint Gregory in the Hours of Henry VIII, accompanied in its reproduction online by an exemplary curatorial description of the nature, history, and setting of the subject. Although less richly and expertly painted, with fewer human “witnesses” present, and deprived of its former manuscript context as well as the name of its artist and its place of production, “our” leaf apparently belong to a similar version of the genre, and perhaps to a similar place in its own book. Within Books of Hours, the illustration of Gregory’s Mass often, fittingly, accompanied the Hours of the Cross or the Seven Penitential Psalms as well as “Gregory’s Prayers”.

Surveys of the surviving medieval corpus of materials with representations of the subject and variations upon its theme, such as the Instruments of the Passion (or Arma Christi) on their own, include the German Gregorsmesse database and the Index of Christian Art at Princeton University, whose resources and staff on site have aided the study and decipherment of this case. Without identifying inscriptions, the interpretation of some objects among the Instruments and the Persons among the scattered heads depend upon their characteristics, attributes, and location, for example as some pairs of heads may depict a particular scene or episode. For a contemporary audience, the various forms of headdress, expression, and demeanor would have conveyed clear clues which to some extent have disappeared from our own awareness of modes of social presentation, given the extent to which customs, fashions, and expectations have changed over the centuries. Fortunately we might find help, for example, in expert guides (for example here) to the depiction of forms of dress in manuscripts in France and the Netherlands during the period of production and early ownership of “our” image. Among many variants of the scene, cases with similar choices of objects and heads appearing in Gregory’s vision include this one.

The Instruments and Individuals

As in many cases, here the Instruments and Participants in the Passion seem to be scattered across, or clustered upon, the background, without identifying inscriptions, as if they challenge the viewer to discern their identities correctly, somewhat like a Riddle or Rebus. Set for the Mass, the altar table carries an opened missal-type book, poised upon a lectern, with double columns of indecipherable text per page; two silver candlesticks supporting tall, unlit white candles; and a gold chalice standing upon a spread corporal, which partly covers a rimmed gold paten. Below the short front of the plain white altarcloth, the pale foreground flanking the celebrant is decorated with branching, scrolling foliage, perhaps emulating an embroidered or brocaded altarfront.

As for the Instruments, how many do you see?

As for the Instruments, how many do you see?

I count the centrally placed tau-shaped True Cross, surmounted by its Titulus, draped with a garment (presumably the Shroud or seamless Garment, not the purple Robe), and flanked by the Ladder for the Deposition at the left and the Column for the Flagellation at the right. The Crown of Thorns rests upon Christ’s Head. The rim of the Sarcophagus appears as an extension beyond the altar table. Between the Cross and the Ladder stretches the Veil of Veronica, bearing the imprint of Christ’s closed-eyed frontal Head. Atop the Column perches the Rooster, facing left, for Peter’s Denial. The Whips (Scourge and Switches) are crossed, right over left, halfway down the front of the Column, with a dangling pair of romal reins of another Whip (or two) which descends from the base of the Switches to the top of the Sarcophagus. Between the unbroken rungs of the Ladder, which leans upon the Cross, rise the long shaft of the Lance and reed of the Sponge. Between their tops hover three Nails for Christ’s Wounds. Suspended, as if scattered, upon the background in counterclockwise formation, there appear three more-or-less identical balustraded Vessels (perhaps buckets, salt-cellars, censers, and/or covered Jars for the gall-with-vinegar and the anointing myrrh); a Hammer and set of Pincers for attaching and removing the Nails; three stacks of Silver Coins for Judas’s price of betrayal; three silver Dice for casting lots for the Robe; the Scimitar for severing the High Priest’s Servant’s Ear; a Lantern for the Arrest; and a Pitcher or Ewer upon a Platter or Basin for service perhaps severally at the Last Supper, the Washing of the Hands, and the gathering of Christ’s Blood.

Seven human Heads, male and female, hover in the background. Those in profile appear to scowl or scoff. Five heads wear headgear. The base of each neck has the rounded neckline of a garment. A helmeted, short-haired, clean-shaven soldier (presumably Longinus) rises above the Veil. Below it, a Mocker or Spitter confronts Christ’s Head, with a brimmed “bag hat”(capeline) and projected, pointed beard which abuts Christ’s hair. To the right of the Column, more-or-less in line with the Veil, there appears a woman wearing a neat white wimple (perhaps Veronica, the Servant Girl at Peter’s Denial, or Mary). In a row to the right appears a bearded, long-haired head tilted outward below the Ewer-with-Dish (probably Christ at the Betrayal, rather than Peter at either his Denial or the Notice Thereof) and the scowling Judas wearing a pendant moneybag at his neck. In a vertical row beside the upright Sword; a glowering figure wearing a high hat with a bilobed top (probably the High Priest Caiaphas) and an imposing frontal figure with an elaborate headdress or diadem (presumably Pilate or, rather, Herod).

Wearing a loincloth, a double-pointed beard, and long, straight hair, Christ opens his eyes and crosses his hands in front of his bare chest, with rays of light as a cross-nimbus streaming from his head. Without visible Wounds, He emerges alive through or despite the Crucifixion. Similar rays extend both from the version of his Head on Veronica’s Veil and the Head of Judas’ Companion. Some other depictions of the Gregory Mass endow other figures than Christ (notably Gregory) with rays of light, so that this case could designate or imply Peter (compromised at the Denial, but rehabilitated and raised to sainthood through subsequent events). However, the features of face, hair, and beard, the rays, and the positioning appear here to designate Christ at the Moment of Betrayal, with a prescient set of rays of light which also pertain to Veronica’s Veil. Wedged between the Ewer, the branching Scourge, and the Lantern, this Companion seems to be hemmed in for the events of Holy Week leading to the Crucifixion and the Re-emergence from the Tomb. Such tokens imply that the “narrative” of the imagery follows a sequence that moves, or might move, from moment to moment, from episode to episode, from implement to implement, and from import to impact in a cycle which follows varying directions and possibilities from top to bottom, left to right, right to left, around and about, and back again, as contemplation, reflection, and reconsideration might direct.

The choices among which Instruments to include, and how to represent them, opt for plenitude as to number of Instruments (among representatives of the genre) and for triplicate in series of objects. That there are 3 Nails (for the spread Hands and the overlapping Feet), 3 similarly-shaped Vessels (perhaps for different types of materials more or-less-viscous and more-or-less vicious applied at different stages of the proceedings), 3 piles of the 30 silver Coins, and 3 Dice, reiterates an emphasis upon trifold entities. That is, in sum, a Trinity. Such emphasis could govern the focus for this illustration, its intended viewer, and, perhaps, within (or at) its full volume.

The Leaf

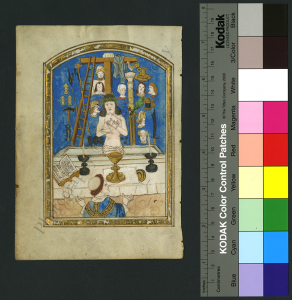

The leaf now belongs to a private assemblage of manuscript and early printed materials. It was purchased, on its own, from a renowned bookseller about 25 years ago. A black-and-white reproduction of the illustration appears in print here (first published in 1995), page 229.

Beginning several years ago, I have had the opportunity to examine, photograph, conserve, and re-frame the fragment, as part of a long-term project described elsewhere on this website. This work included the preparation of photographs with different lights, backgrounds, cameras, and lenses, experimenting with different methods and responding to various aspects of the artifacts themselves as the research developed.

The time has come to illustrate the leaf, on both sides, and in detail, as a contribution toward the study of this artifact, its genre, and the group of medieval and early modern materials to which it now belongs. In my Handlist of those materials, this leaf is Number 13. [Future posts, starting here, describe the Handlist and its components.]

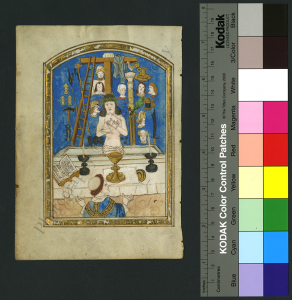

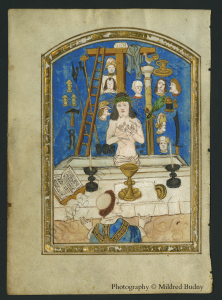

First, to show its scale and the brilliance of its colors, including gold, we exhibit an image of the leaf in full, with both a standard scale (both inches and centimeters) and color-guide. The presence of the color guide within the image can demonstrate — even at first glance — the degree of fidelity of the color reproduction which this shared method of digital transmission permits (or not), as it passes from screen to screen, from device to device, and from viewer to viewer.

The Full Extent of the Leaf, plus Scale and Color Guide

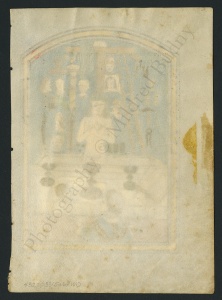

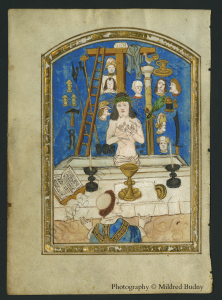

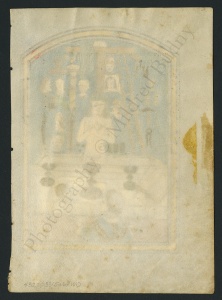

Although the “interesting” part of the leaf — for those who (like Alice) prefer their books to have pictures — would be the illustrated side, it is worth showing the other side, too, for what it’s worth.

The Front and Back, Revealed

Recto

Verso

It is worthwhile to see what the leaf, in all its surviving glory, both has and does not have. No text, not a bit, apart, that is, from the 20th-century seller’s code in pencil at the bottom left (‘4327Ø3315o67W0’), the schematic lines of “text” on the celebrant’s opened book, and the partly effaced Monumental Capitals of the Latin Titulus (“Label”) of the Cross, with the acronym INRI abbreviating Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudaeorum (“Jesus the Nazarene, King of the Jews“).

The Titulus

So, apart from that Titulus, the leaf itself carries no original text as such to indicate what language(s), form(s) of script, numbers of lines of text per page, and specific genre of prayerbook pertained to the manuscript to which this now-solitary leaf once belonged, nor the place which it held within the sequence of the book, apart from somewhere in the “middle” and within a binding. The size of the leaf implies that the main text occurred in single columns. The language may have been Latin and/or a vernacular. The professionalism of the painted illustration and the use of gold leaf and powdered gold among its pigments indicate a production of some quality and expense. Some details of the execution — like schematic facial features and the overshot outlines of the outer contours of the frame as they rise from the left-hand side into, and partly over, the curved top of the frame — demonstrate an approach somewhat below the highest order of meticulous craftsmanship and artistry.

For a while when I first encountered the fragment, it could be viewed only behind the glass and mat of the gilded frame into which its owner had placed it. This setting allowed a view only of part of the illustrated side, “cropped” by the window of the mat to a narrow margin around the arch-shaped border of the scene. (As you see at the top of this Post.)

The considered decision to remove the fragment from the frame, to release it from the non-archival mat and backing, to conserve and photograph it, and to re-frame it (with archival materials) allowed the opportunity to see the full extent of the leaf, that is, insofar as its historical spoliation permits.

Clues

Thus revealed are the surviving extents of the margins, the notched edge of the stitching line at the former spine of the leaf, and consequently the former layout of the leaf as recto and verso. It is clear that the originally blank flesh side and the illustrated hair side of the animal skin were turned to the front and back respectively. Within the volume, the illustration faced the opening of its companion text, after the “blank” page at the end of the preceding text.

Orange pigment offsets from the (lost) preceding verso

Stitching notches (bottom here) and red stain traces (at right)

Revealed, too, are some other tell-tale features. They reveal aspects of the processes of production and characteristics of the volume apart from the image itself.

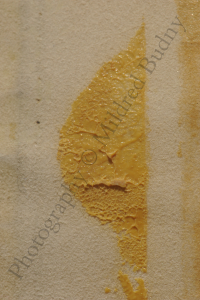

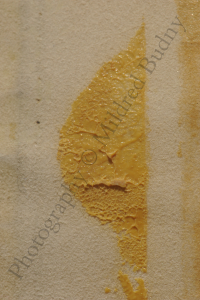

For example, the offsets of a pair of curved segments of bright reddish orange pigment on the “blank” recto migrated from the formerly adjacent page, perhaps part of an initial in an upper line of the text.

The faint traces of reddish stain at the lower edge of the leaf indicate colored treatment which it must have shared with the other leaves in the rest of the closed book-block.

Pricking holes lower on the frame

Pricking holes for the frame

The closely spaced pricking holes made to delineate the outer contours of the frame and some other parts for the illustration have pierced the leaf, with partly blackened edges from corrosion of the metallic traces left by the sharpened implement. On the “blank” side, these holes emerge more clearly into view. The yellowish “gunge” comes from an unknown stage in the history of the fragment.

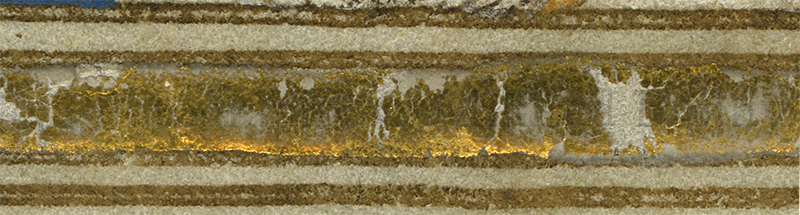

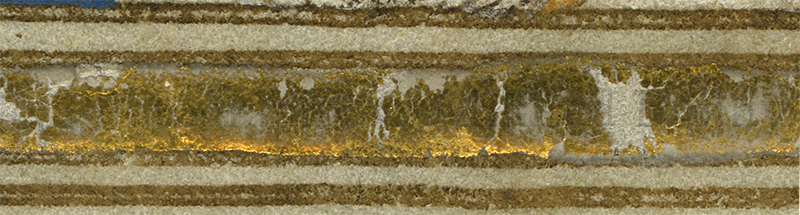

The clear background revealed between the surviving portions of the gold leaf, where other portions have flaked or lifted away, indicates the uncolored form of adhesive used in its application. In addition, the illustration employs powdered gold pigment, adding highlights and rays of light.

The pair of darkened stains at the outer edge of the leaf may bear witness to clasps for the volume. The notches along the inner edge, severed by an uneven cutting line from its former stub or adjacent leaf in its original bifolium, demarcate the stitching stations for the binding, in accordance with widespread medieval bookbinding practices, in this case 5 stations.

Layers of pigment, including powdered gold

Such traces could help to confirm the identification of other parts of the same volume, should they survive. In the absence of a specimen text-page, this leaf must await other methods of discovery than, say, the convenient and widely employed searching method to reunite (even if only virtually) books and their fragments by number of lines per column and per page.

It is a pity that this leaf has been forcibly removed from its original manuscript setting, presumably for commercial purposes, but it is useful to recognize that, at least, the despoiler did not trim away all traces of the former margins and sewing line. In such ways, the leaf itself, when revealed in the processes of conservation, photography, and uncropped reframing, can show clues about its former book that the cropped image alone fails to do.

Set “free” in such a way, it might direct our research more surely to its former “home”, even if that reunion might have to remain within our imagined or “virtual” reconstruction. Such a process could befit the aims of the image, intended to evoke reflective meditation upon the nature and significance of its subject-matter across the instances of time and place.

The Fragility and Tenacity of Gold Leaf

*****

Photography © Mildred Budny

High-quality images suitable for reproduction may be available upon request to director@manuscriptevidence.org.

Perhaps you know where other parts of the original manuscript may survive? We would be glad to hear from you.

Please leave a Comment here, Contact Us, or enter into a conversation with us on Facebook.

*****