A Thirteenth-Century Pocket Vulgate Bible

at Smith College:

“The Dimock Bible”

(Mortimer Rare Book Collection MS 240)

Hannah Goeselt

RGME Guestblogger

[Posted on 30 October 2023]

Note: For this Blogpost, we welcome Guest Blogger, Hannah Goeselt, who reports on a manuscript which first caught her attention when examining manuscripts at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, as part of her undergraduate studies. Now, having recently finished an MS at Simmons University in Library and Information Science (Cultural Heritage Informatics), she offers a guided tour to this book deserving wider attention and further research. We thank her for her contribution and invite you to join this guided tour.

As part of the tour, Hannah showcases the manuscript for its interest in its own right, and also, as she says, “to use it as an example of how one might go about using some of the online research tools out there to assist in manuscript studies”. Accordingly, she includes “everything from the De Ricci census, Conway–Davis directory, Schoenberg database, and Digital Scriptorium (with Smith’s own consortium database)”, as well as the Grolier Club, “which played an important part in assessing the content of the auction catalogs mentioned in Schoenberg”. Brava!

Over to you, Hannah . . .

Our Guest Manuscript:

Mortimer Rare Book Collection MS 240

Smith College, MRBC MS 240, fol. 191v. Historiated initial for the Pauline Epistle to the Ephesians, with outward-looking male face. Photography by Hannah Goeselt.

While taking survey of material pertaining to manuscripts from Otto F. Ege (1888–1951) in collections across the campus of Smith College, I was drawn to this thirteenth-century Pocket Bible, with the pressmark “MRBC MS 240″, and thought it’d be worth initiating a sort of “meet-and-greet” with this codex. I have a fondness for 13th-century Latin Vulgate Bibles, often noted for their similarities and their contribution to forming our current concept of the Bible’s format. And yet within all that seemingly mass uniformity, on second glance they all contain their own unique qualities and histories.

At the Mortimer Rare Book Collection (MRBC) at Neilson Library, several jewels of medieval manuscripts among keep this book company, alongside a host of fragments. Notable examples are

- a large-scale Vulgate Bible written in a single column layout,

- a lovely mid-thirteenth-century French Psalter with early-modern devotional marginalia,

- a Book of Hours associated with Philip the Good, Duke Philip III of Burgundy (1306—1467, duke from 1419).

All three of these have featured on posts in Peter Kidd’s blog on Medieval Manuscripts Provenance:

- “A 13th-Century Bible from Beauvais at Smith College”

https://mssprovenance.blogspot.com/2014/12/a-13th-century-bible-from-beauvais-at.html

- “A French 13th-Century Psalter at Smith College”

https://mssprovenance.blogspot.com/2015/07/a-french-13th-century-psalter-at-smith.html

- “An Unrecognised Book of Hours Made for Philip the Good [Part I]”

https://mssprovenance.blogspot.com/2015/12/an-unrecognised-book-of-hours-made-for.html

They, along with many others, are available on the Digital Scriptorium website. However more recently the collections have also been added to the Five College Compass website, where MS 240 has joined them with a full digitization:

For users of the Smith College Libraries database (Students, Faculty, Staff, Community Borrowers), this is internal Permalink for the manuscript.

Let us, for the duration of this post, call it the Dimock Bible, as referred to in the Directory of Collections in the United States and Canada with Pre-1600 Manuscript Holdings (pages 52 and 62) by Melissa Conway and Lisa Fagin Davis, and due to the family name associated with its recent ownership. Within the library record, we see that the cataloger of this manuscript has done wonderful work in linking the manuscript to two very important sources that will help us in our search for more information.

Upon opening, we are met by the first page of the Bible text, which opens the preface to the bible unit itself by its translator Jerome (circa 342–347 – 420), who produced the Latin Vulgate Version. This image is omitted in the digital facsimile, though one can see a painted offset on the verso of the preceding leaf.

Smith College, MRBC MS 240, fol. 1r. Opening of Jerome’s preface ‘Frater Ambrosius’ for the bible unit. Photograph by Hannah Goeselt.

“The Dimock Bible”:

From George Edward Dimock, Father and Son,

to Smith College

Looking at the metadata, we can see the manuscript was recorded in 1937 by Seymour de Ricci (1881-1942) under Dimock in his Census of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts in the United States and Canada, as number 1159. Looking up the entry, we see it comes with an introduction:

The owner kindly informs us that he has inherited from his father five early manuscript items, which he lists as follows:

[1] Bible, extensively illuminated, having belonged before 1676 to Cardinal Benedetto Odescalchi, later Pope Innocent XI (1676–1689) . . . (page 1159).

Northampton, Massachusetts, Smith College, Mortimer Rare Book Collection, MS 240, inside front pastedown with bookplate. Image via https://compass.fivecolleges.edu/object/smith:1365930#page/2/mode/2up.

The ‘owner’ mentioned in that introduction was one George Edward Dimock (1891–1966), who taught Classics (and tennis) at the Pingry School in Elizabeth, New Jersey, where he had been born and was currently living at the time of the Census. A graduate of Yale University, he retired as instructor in 1950. His Obituary appeared as “George E. Dimock”, New York Times (January 13, 1966), page 25. His wife was Imogen Kinsey Dimock (1893–1985), Vassar College Class of 1914.

As stated in de Ricci, Dimock had inherited the manuscript along with the rest of the library belonging to his late father, also George Edward Dimock (1854-1919). It is his bookplate we see on the front inside board over the marbled pastedown.

The elder Dimock, like many men in his family, studied at Yale University, where despite studying medicine he went on to become a stock exchange broker in 1877. Among “Owners of Incunabula” listed by the Consortium of European Research Libraries (CERL), he is listed as Dimock, George Edward, with six items all now at Smith College.

In 1881 he would marry Elizabeth Jordan, an elder sister of Emily Clara Jordan Folger (1859–1936), co-founder of the Folger Shakespeare Library. For an added connection to Smith, their eldest sister, Mary Augusta Jordan (1855–1941), would teach English at Vassar before later becoming one of the formative faculty members in Smith College’s early history.

“George Edward Dimock”, Biographical Record of the Class of 1874 at Yale College, Page 65, via https://archive.org/details/biographicalreco00yalerich/page/64/mode/2up.

Of his library, the elder Dimock writes in 1910 for his class’s biography at Yale that “a great interest has always been the collecting of books, and I derive great satisfaction from the contemplation of my library, which, while not notable, contains something of interest for every book-lover.” (“George Edward Dimock”, Biographical Record of the Class of 1874 in Yale College, Volume 4: 1874–1909 (New Haven: Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor, 1912), pp. 64–67, at page 67 via The Hathi Trust, or page 65. via Internet.org).

The second Dimock’s widow, Imogen Kinsey Dimock, gifted the manuscript, along with several Italian volumes and incunabula containing Bibles, Biblical literature, and other related texts, to Smith in 1968, two years after his passing.

Their son, also named George Edward Dimock (1917–2000), had followed in his father’s footsteps, by becoming a professor of Classics, first at Yale (1948–1952), then later at Smith College (1952–1986).

The Schoenberg Database and Sales Catalogues

Northampton, Massachusetts, Smith College, Mortimer Rare Book Collection, MS 240, front cover. Image via https://compass.fivecolleges.edu/object/smith:1365930#page/1/mode/2up.

The second link in the record takes us to the (Schoenberg Database of Manuscripts ), a wonderful tool for tracking manuscript provenance, by creating linked entries of past references to a manuscript as it moves through time and different collections. This now allows us to inquire about the appropriate sales catalog to analyze their description.

The Dimock Bible, recorded as SDBM_MS_23713, has four entries associated with it with Provenance data:

- SDBM_239187

- SBDM_237243

- SBDM_8899.

Two of them locate traces of its ownership before the family, the first in 1891 (lot 4) in the sale of the Library of the Late Hon. George Wood [(1828-1884)], M.L.C. [Member of the Legislative Council] of Grahams Town, Cape of Good Hope.

Biblia Latina, Manuscript on Vellum, with numerous initial letters painted in brilliant colours, red morocco extra, with arms of Cardinal Odescalchi in gold as centre ornaments on sides. [lot 4]

The entry for the manuscript (no. 142) in the catalogue for the auction in June 1903 in London by Messrs. Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge of the library of the late W. E. Bools, Esq. — i.e. William Edwin Bools (1837–1902) — of Enderby House, Clapham, describes it thus:

written in minute but clear gothic letters, double columns of 48 lines, by an Anglo-Norman or Northern French scribe, numerous fine painted strap and other ornamental initials and marginal decorations . . . old Italian red morocco, full gilt floreate back, line and ornamental frame sides, with arms of Card[inal]. Odescalchi afterwards Pope Innocent XI on sides. [no. 142]

The lengthy title for Bools’s library in the catalogue and the circulation of presale advertisements focused mainly on the collection’s Shakespearean-era literature and other such prominent English writers.

The Earlier Provenance

and Likely Origin of the Manuscript

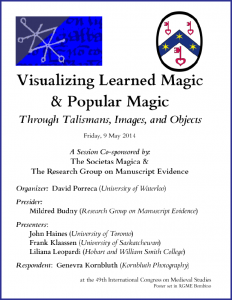

Marseille, Musée des beaux arts. Carlo Maratta (1625-1713), oil on canvas. Portrait (between 1645 and 1658) of Cardinal Alderano Cybo. Image via Wikimedia and Creative Commons 3.0.

The reference to Odescalchi, which has allowed others to trace the manuscript into the 19th century, is based on the red leather armorial binding: a cardinal’s typical wide-brimmed hat and tiered tassels over the family device.

But the identification to that family was found to be incorrect, and has since changed, upon further investigation of the device, to that of Cardinal Alderano Cybo / Cibo / Cybo-Malaspina (1613–1700; Cardinal from 1645). Belonging to member of a family from the Italian aristocracy in the region of Genoa, his arms still have a papal connection, as this individual served as Cardinal Secretary of State to Pope Innocent XI, born Benedetto Odescalchi (1611–1689).

With the mis-attribution in mind, one begins to wonder what else about these descriptions were in error. The assertion regarding the scribe as Anglo-Norman of Northern French origin assumes increased interest when we look through the manuscript, since its script and decoration, like its binding, seem much more Italian in origin than French. If you would allow me to indulge in this theory (and I welcome other potential ideas), this observation could well challenge the ways that we view and research this bible.

In the script, the hands gravitate towards a Southern textualis than its more angular, Northern sibling Gothic textualis. This preference accompanies the consistent use of tironian ‘et’ (“and”) with no crossbar, and an ad-hoc approach to whether its chapters for biblical books are set in the margins or within the text-block. We will return to details about the chapters in a moment.

From an aesthetic standpoint though, it is the decorated initials that have the softer edges and palette I’ve come to associate with Italian production. One might compare its initials with these examples:

- Genesis in MS 6 of the University of Edinburgh, MS 6 (such as folios 148v–149r)

- the Morgan’s MS M.178: New York, Morgan Library, MS M.178, such as folio f.147v

The Decorated and Animated Initials

While technically the book is not “illuminated” or even “historiated”, with illustrations of figural scenes as such, it does indeed have initials painted in brilliant color: vibrant blues, greens, shades of red-orange and pink-purple, all accented in white penwork. The letters terminate in simple foliate designs as well as human body parts, the initials as likely to sprout multi-colored leaves as an arm, bare foot, or figure’s face. This is fairly consistent throughout the save four examples.

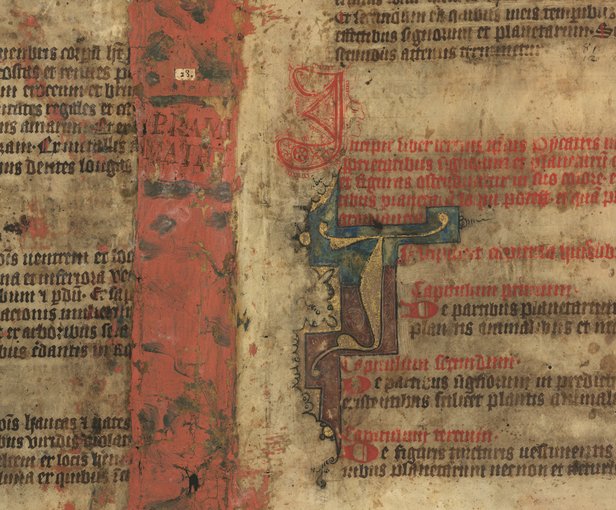

There are two zoomorphic initials made up of the twisted limbs of fearsome dragons made to resemble their opening letter. The more impressive of the two marks the beginning of the Book of Proverbs. Within its border, this creature adopts the form of the letter P (for Parabole), as it curls its long neck to bite its own leg, while raising its offside leg and offside wing. The spread tail-feathers almost resemble rays of light beaming behind the beast.

Smith College, MRBC MS 240, fol. 25v. Proverbs Initial with Dragon. Photography by Hannah Goeselt.

Two more inhabited initials feature respectively another dragon hanging by its neck to form the tail of the ‘Q’ opening I John (“Quod fuit ab initio . . . “), and a full figure of what I can only assume is the prophet Jeremiah himself standing within the initial V of his Book starting “verba hieremi[a]e filii elchi[a]e . . . ”. When seen directly in person, the initial is quite small, but in enlarged photographs or under magnification we can see a bespeckled and bearded elder leaning on a walking stick and contemplating an object — flower, scroll, or roll? — which he holds in his hand.

Smith College, MRBC MS 240, fol. 69v. Jeremiah Initial.

The Production of Portable Vulgate Bibles

The distinction between French and Italian features is important because, with a new region or locale in mind, the context of some smaller details pertaining to the manuscript’s usage become of interest.

Portable Vulgate Bibles produced in Italy during the thirteenth century were heavily influenced by the Paris Bible system, developed in the sphere of the university. The system included a certain ordering of Biblical Books, contained within a single volume, a diminished size for the book and script, the omission of some features, such as the capitula (or chapter) lists, their replacement with the full use of Jerome’s prologues, and an integration of the glossary of Interpretationes nominum Hebraeorum (“Interpretations of Hebrew Words”). More importantly, the Paris Bible adopted a chapter system and numbering that has persisted into the present day.

In this context, as the term has sometimes been expressed too loosely, I am taking note of a specific grouping of thirteenth- century bibles defined by Laura Light[1] that proliferated after 1230 and into most of the rest of the century. Not all Bibles of the thirteenth century are Paris Bibles; not even all those made in France are Paris Bibles (though a good half of them certainly are), and vice versa. Not all Paris Bibles were made in Paris or, for that matter, in France.

As more research on the development and production of thirteenth-century Bibles might reveal all the variations between what, at a cursory glance, may seem a more-or-less consistent genre, we can start to see how manuscripts made further away from locales under the influence of Paris Bibles made do with whatever exemplars were at hand, and are therefore given to greater deviation from the ideal laid out by Neil Ker (1908–1982). These thoughts were greatly improved by observations by Laura Light about such research results, as she described in the 2023 Autumn Symposium.

In an article on the subject of Italian vernacular Bibles[2], Sabina Magrini observes that certain owners, like Italian friars, were accustomed to working with the Paris Bible, and if the text did not match expectations, then a re-adaptation of the manuscript might occur. We see this personalization paralleled throughout the text of the Dimock Bible, where signs of consistent revision to chapter numerals, either erased or added to, are made by a former owner.

Marks of and for Consultation

Following on that thought, it was these manuscripts made outside of the Paris Bible’s influence (namely Bologna), or at least partially outside it (as its ordering of books seems to follow the Paris sequence), that would often draw on older or alternative systems of numbering chapters. It was thus up to the reader to bring it into alignment with the modern system. We see frequent evidence of this practice throughout the book, with an ‘I’ added to the end of a numeral, partial or wholly rubbed out chapter numbers, or simply an amended version placed in the margins.

Divisions mostly occur at the same placement as new system, and most +alterations are only off the standard by several numbers, as noted in this page from Proverbs, where a reader has used + erasure and a black ink to change the +roman numerals to 20, 21, and 22 +(XX, XXI, and XXII) from an initial state which seems to have been marked as 17, 18, and 19 (XVII, XVIII, XIX).

While we are on this page I hope you will also admire, in the bottom margin, the red pen drawing of what looks like a crane or egret, holding in its bill a little leaf which descends from the foliate tip of the initial M in the last line.

Smith College, MRBC MS 240, fol. 29v. Egret in the margin. Image via smith_1365997_JP2_37a4896918dcf45f89c0d5adcb45b9a88c9745ff6826edaa76f294e7cd4f24b6.

This Bible does not contain the Interpretationes, not even as a consequence of more missing sections, which it certainly did acquire. The major loss of sections is not noted in any of its auction descriptions, though this omission might be inferred from its foliation that only counts its 214 medieval leaves, and affirmed in the catalog record contents that states Exodus through Psalms completely missing.

The manuscript has clearly seen much use in its day, seen in a number of annotations that are worth looking into, including lists of numbered references in several different hands. Multiple fine examples occur of one of the more memorable forms of note-taking in the middle ages, the “nota bene” mark — a monogram made out of the letters forming the word ‘nota’, urging the reader to take special note of the text it is placed next to. The Dimock Bible is full of such symbols, occasionally varying in form, but clearly signaling an attendant reader (or probably a series of readers) that might wish to come back to certain passages again and again.

As only one example among many, next to Isaiah 40:26 we see an asterisk-like mark which stands beside an annotation expanding in the outer margin as “co[n]ve[r]tim[in]i ad me om[ne]s fines terr[a]e quia ego d[omi]n[u]s d[eu]s v[i]r…” (etc., etc.). This mark, made of an oblique stroke over a pair of dots, is one of an identical pair of signes-de-renvoi. It signals the start of an ‘omission’ added in the margin; its match within the text signals the place where these words fit within the course of the passage. Its twin rests below line 6 of the text, between “hec. qui“. (Curiously, that addition does not appear to correspond with missing text at that point.)

Further down, the modern Isaiah ch. 41 is created out of the rubbed-out remains of the roman numeral XLVIII (48).

Smith College, MRBC MS 240, fol. 62r. Isaiah 40 and marginal annotations. Photography by Hannah Goeselt.

If that weren’t enough, beyond the bible’s textual organization and reading usage, there are two peculiarities that make the manuscript stand out from the crowd.

Scribal Hands, Blank Leaves,

and a “Seal Impression”

— or, “Things Found in Books”

Smith College, MRBC MS 240, fol. 14r. Image via smith_1365987_JP2_af282895264177048758c4fe965464e8afaa7080844dc41e5f35586dbc167837.

A quire in the Book of Genesis is done by a different hand (see Genesis Anomaly), with wildly different decoration to go with it — such as this wolf that forms the U (or V) of Venit in Genesis 35:6 (“Venit igit[ur] iacob luzam qu[a]e . . . “). With an upright back, the creature spreads its forelegs beside the text and raises its tail to foliate terminals above the top line.

These leaves appear to have been added early in the history of the use of the book, due to the presence of marginal notation in the same medieval hand as other sections, if only to make brief comments and manually add in chapter numeration. The chapters are a necessary addition on the user’s part, as the original schema for this quire has none.

Three blank leaves, containing ruled lines but never written on, precede the continuation of the first program of artist and script, now beginning the Book of Proverbs. It remains unclear why the added material did not continue on with the other missing books. One possible theory that could account for the missing book portions despite the added quire is that the outlier came from a separate manuscript entirely, and was the result of an attempt to supplement missing material from the main codex at a fairly early point in its history, enough to have some of its marginalia included in this section.

The issue at hand comes down to whether this quire was made specifically to repopulate this Vulgate manuscript or if it was scavenged from another source entirely. If more quires existed, it would account for at least one mystery of the bible, as this outlier quire is stamped with its own history separate to being bound within this current volume.

Smith College, MRBC MS 240, fols. 24v-25r, with impression on page facing the opening of the Prologue to Proverbs. Photography by Hannah Goeselt.

Smith College, MRBC MS 240, fol. 23v, detail. ‘Seal’ impression, turned upright. Image via smith_1365987_JP2_af282895264177048758c4fe965464e8afaa7080844dc41e5f35586dbc167837.

The firm outline of a lozenge-shaped impression is visible across the blank leaves, and shows a stark break in book continuity from page to page. When its image is viewed upright, we see a standing figure in a mid-length tunic loom just behind a second, kneeling, figure turned away, arms raised in prayer. The first figure holds some kind of tall object in his hand, though the impression is obscured enough that it is unclear as to its nature. Surrounding the two are illegible markings that on its source would become text now just out of our reach.

In the catalog record, the current theory is that this is the result of a pilgrim’s medal. This is certainly not a bad theory, as there is evidence for such object being kept in books (even sewn onto the parchment, as in the case of Getty Museum Ms. 5 f.64)[3]. In her blog posts focusing on this mystery, Brittany Osborn proposes that it is the effect of a wax seal, with another theory that it is the seal matrix itself[4]. (However, as Mildred Budny noted in conversation, a matrix could very well have been pushed into the surface, but its backing would have prevented it from resting between leaves.)

Whether a pilgrim badge or seal, it should be reiterated that the object itself never rested within the bound book, rather showing through the final leaf of the outlier quire onto its preceding folios without continuing on to Proverbs and the original program, which leaves us with the possible scenario that the object resting underneath the unbound quire, and being left in this spot for some time with a deal of pressure before being added to the rest of the manuscript.

This feature has been previously noted and expanded upon in two posts from Osborn’s blog “Manuscripts: Illuminating the Mysteries in the Margins”, as part of the Five College Consortium’s study and catalog of its collective holdings (combining that of UMass Amherst, Mount Holyoke, Smith, Amherst, and Hampshire), and initial contributions to Digital Scriptorium. Her analysis of the overlapping impressions in the parchment of a vessica-shaped seal may be seen in Behind the Impression.

In her blogpost, Osborn proposed a compelling parallel example of such a seal, found through the “UK detector finds database”, with a pair of full-length human figures in some form of opposition or attendance, respectively standing and kneeling, and a similar size, but not the exact match. (See http://www.ukdfd.co.uk/ukdfddata/showrecords.php?product=34719&cat=44 — although currently “The database is closed for update” [as seen on 6 July 2023, 14 July 2023, 12 August 2023, and 11 October 2023; login required]). I am inclined to agree that the image depicted in the center (the “device”), within the scarcely legible inscription (the “legend”), probably comes from the life (or death) of a martyr saint such as Thomas Becket (1118 or 1120 – 1170), Archbishop of Canterbury, or the Protomartyr Stephen the Deacon (5—34 CE).

Portable Antiquities Scheme, ID LEIC82C839. Medieval copper-alloy seal matrix (front and back), found in Leicestershire, along with its seal impression. Image by Creative Commons By attribution, via https://finds.org.uk/database/artefacts/record/id/899948.

A rather similar approach to the pair of figures appears on a copper alloy seal matrix found in Leicestershire, ID 899948. Its entry for the Portable Antiquities Scheme describes it thus:

The motif is of a man kneeling in prayer with a standing figure behind, who is standing facing away but with head turned towards the figure and a staff or sword? brandished over his head as if to strike. The image suggests the martyrdom of St.Thomas a Becket?

Further research might reveal more about the object formerly placed between the pages in the Dimock Bible, with its image turned upside-down within the book. For example, depending upon whether it might have been a seal or the matrix which would have formed the mold for seals, the impression as we view it could represent the ‘positive’ formed by a matrix, or the ‘negative’ produced by a seal. Within the scene, the identity of the object held by the standing figure could determine whether the interaction is benign or destructive.

An Erased Inscription

On the final verso, further potential insight into the manuscript’s provenance leaves us with one more tempting mystery at the end of our meeting with it. Traces of a faint 4-line inscription at the top remain from a statement that probably functioned as an ownership inscription. The statement has been scraped off rather thoroughly, although, even with just the naked eye, ghostly letters make their way to the surface.

1) Direct View

‘Flyleaf’ Erased = Smith College, MRBC MS 240, folio 214v.

2) ‘Inverted’

Inverted flyleaf = Smith College, MRBC MS 240, folio 214v. ‘Flyleaf’ Erased

Though I am interested in the possibilities of multi-spectral enhancement with photo manipulation programs, I am far from an expert on the matter. It may take visiting again, in person, with a black light or similar method to reveal anything more legible. Here, I have used the computer program ImageJ to “invert” the colors which has produced clearer letters here and there, but does not approach something that can be fully read.

To conclude, I hope you have enjoyed this small introduction to what I consider a worthy addition to the corpus of 13th-century Bibles and their related studies. It just goes to show that even straightforward-seeming genres as this contain hidden depths and unique personalities that, aided by close examination as well as the digital tools and resources at our disposal, may be coaxed out for our enjoyment.

Smith College, MRBC MS 240, side view of binding. Photography by Hannah Goeselt.

*****

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to M. Budny who shared her time, patience, and expertise in a number of points to this blog, including her thoughts on seal matrices and their compositions.

Further Resources

De Hamel, Christopher. “Portable Bibles of the Thirteenth Century”. In The Book: A History of the Bible. London, New York: Phaidon Press, 2001.

Light, Laura. The thirteenth century and the Paris Bible”. In New Cambridge History of the Bible (New Cambridge History of the Bible), 380-391. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Ruzzier, Chiara. “The Miniaturisation of Bible Manuscripts in the 13th Century: A Comparative Study” In Trends in Statistical Codicology edited by Marilena Maniaci, 65-86. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110743838-003

Magrini, Sabina. “Production and Use of Latin Bible Manuscripts in Italy during the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries.” Manuscripta 51, no. 2 (2007): 209–57. https://doi.org/10.1484/j.mss.1.100105

Melzer, Libby. “‘A Pocketful of Miracles’: The Small format Paris Edition Manuscript Bible at State Library Victoria.” La Trobe Journal 103 (September 2019): 69–83.

*****

Notes

[1] Light, Laura. “French Bibles C.1200-30: A New Look at the Origin of the Paris Bible,” The Early Medieval Bible; Its Production, Decoration and Use. Ed. Richard Gameson, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1994).

[2] Magrini, Sabina. “Vernacular Bibles, Biblical Quotations and the Paris Bible in Italy from the Thirteenth to the Fifteenth Century: A First Report”. In Form and Function in the Late Medieval Bible, Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill (2013): 238-40.

[3] Martin, Rheagan Eric. “Peregrinations of Parchment and Pewter: Manuscripts and Mental Pilgrimage” in Towards a Global Middle Ages. Getty Publications (2019): 246-48.

[4] https://manuscriptroadtrip.wordpress.com/2013/09/21/manuscript-road-trip-autumn-in-the-berkshires/

*****

Extra Comments

Mildred Budny, RGME WebEditor, fascinated by the features of the manuscript, including the curious impression between the sheets in the Genesis portion, as Hannah describes them for us, offers a few comments:

A vessica shape for a seal/matrix in itself does not necessarily denote an ecclesiastical (or monastic) seal. Unless sufficient indication survives in the inscription to indicate ownership by an ecclesiastic or other communal religious community, or person of such capacity, it might be cautious to allow for the possibility that the object might have pertained to a lay individual or entity. Also, might we know about traditions of seal production in Italy and, say, the Veneto region, given the indications of origin and perhaps use there?

Some thoughts about the two figures, both seen in profile. For example, does the kneeling figure have a tonsure? The bare head and short, knee-length, tunic of the standing figure presumably rule him out as a knight intent upon assassinating Thomas. There are no flying projectiles, as in the ‘Stephen seal’, nor does the standing figure raise a hand apparently with such intention. Does that figure, with partly bowed head, hold something like, say, a censor, as an (obedient) attendant for a praying suppliant or officiant?

The impression left in the manuscript and this blogpost by Hannah offer a serendipitous opportunity to bring together several seemingly distinct strands of RGME research and interests. For some years now, the RGME has engaged in research on seals and seal matrices, and hosted sessions with papers on them and their contexts.

We welcome Hannah’s guided tour to this manuscript and its multiple features.

*****

Editor’s Note

We thank Hannah for her guided tour to this manuscript and available reference resources for it. We look forward to learning more about her work as it advances.

She has reported on other aspects of her work for RGME Symposia, so that we have been able to glimpse something of her diverse range of interests. See:

She brought to our attention a leaf from one of the manuscripts our blog visits and revisits:

As Hannah’s blogpost joins our RGME blog on Manuscript Studies, we invite you to visit other posts about manuscripts, Vulgate Bible manuscripts, documents, seals, fragments, and other material evidence from the medieval and other periods. See the Contents List.

We hope to hear more sometime from Hannah Goeselt, Guest Blogger, about how her explorations of manuscripts progress, and what discoveries they bring. Thank you, Hannah, and good fortune with your quest!

*****

Questions and Suggestions?

Do you recognize these scribes and scribal artists in other manuscripts? Do you have suggestions about the date and place of origin of this manuscript? Do you have thoughts about the ghost-like impression between its sheets, perhaps from a seal or seal-matrix?

Please leave your Comments here, Contact Us, or join the conversation on our RGME Facebook page.

We look forward to hearing from you.

*****

Some of his contributions:

Some of his contributions:

Baltimore, Walters Art Museum, MS. W.148, folio 33v, detail. Image via Creative Commons.

Baltimore, Walters Art Museum, MS. W.148, folio 33v, detail. Image via Creative Commons.