Gathering Waifs and Strays among Manuscript Fragments

Dispersed to the Winds of Change

Their Recognition for What They Are

Can Emerge Through Chance Discoveries as Well as Dedicated Expertise

As Part I in a series, Mildred Budny reflects on recognizing the familial connections of ‘orphans’ among dispersed manuscript leaves. Part II considers a group of them as ‘Lost and Foundlings’.

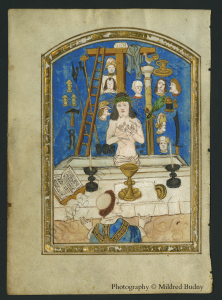

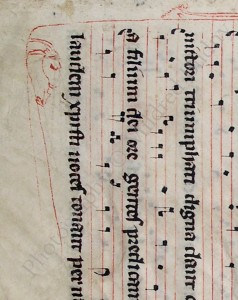

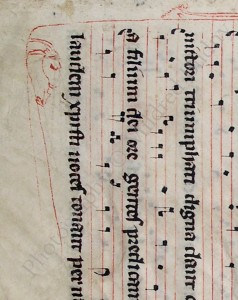

Initial D on a detached bifolium, printed on vellum. Photography © Mildred Budny

‘Do the right thing’, we often hear. Yes, presumably, that seems worthwhile, given the chance, ability, or will. But how to do it and what to do?

Doing the Right Thing for Historical Records? Hmm. Preserving artefacts and monuments from the past is not always straightforward, nor always deemed desirable. The issues remain subject to controversy and concern. When it comes to old manuscripts and their fragments, the set of choices could depend upon opportunities, determination, and intention, as well as, on occasion, serendipity.

Foundlings, Given the Chance

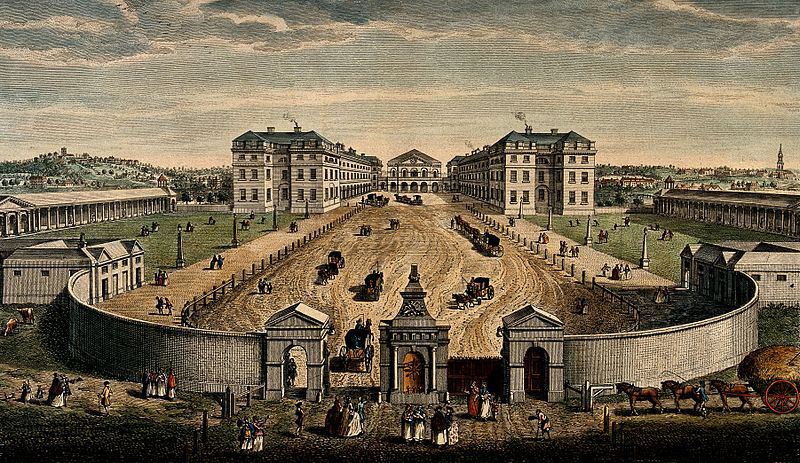

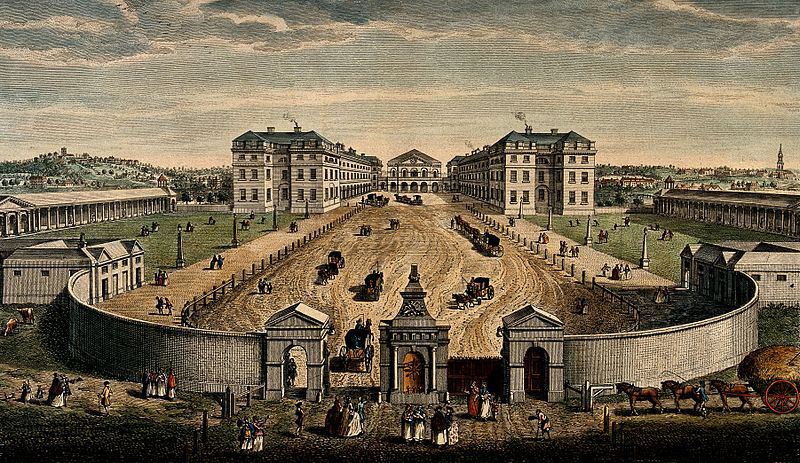

Recently I have been thinking about the humanitarian purpose and activities of the 18th-century foundation of the Foundling Hospital, whose grounds I used to visit during my long postgraduate years in London. Now my thoughts focus on that place, and its place in history, not only in its own right, but as a metaphor or model for the challenges and opportunities in gathering together the orphans, waifs, and strays among despoiled manuscripts and books of earlier ages.

The Foundling Hospital, Holbourn, London: A bird’s eye view of the courtyard. Coloured engraving by T. Bowles after L.P. Boitard (1753). Wellcome Images (wellcomeimages.org) via Wikimedia Commons

These reflections have come to mind as I work to shape the illustrated Handlist of a group of medieval and early modern manuscript fragments and documents, plus some early printed materials, which I have had the opportunity to photograph, conserve, and study for some time (as reported, for example, on this website and in a close-up). By its owner’s wishes, for now the group is called an ‘Assemblage’ because its group was assembled over decades less specifically or purposefully than a ‘Collection’ as such might imply.

Recently, during the accelerated course of the work on the materials as a group, there has appeared the poignant illustrated blogpost by Erik Kwaakel showcasing a group of handwritten tags intended to identify, and to accompany, children who passed through the Holy Spirit Orphanage (Heilige Geest- of Arme Wees- en Kinderhuis in Dutch) in Leiden in The Netherlands in the 15th century. These brief slips can or must stand now for their bearers, long gone into the past, perhaps with little or no other written record for their living existence.

Manuscripts and Foundlings: somehow they interrelate. Manuscripts as Foundlings, and Human Foundlings with Manuscript Tags. Poignant predicaments, and poignant traces. It seems a mercy that any traces may remain to bear witness to the lives, and also the books which any lives have produced, owned, read, perhaps enjoyed, and lost. The time has come for finding, and for caring.

A New Handlist for a Group of Manuscript and Early Printed Materials

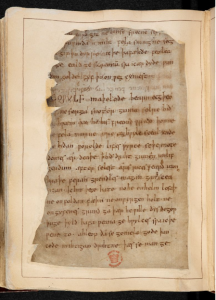

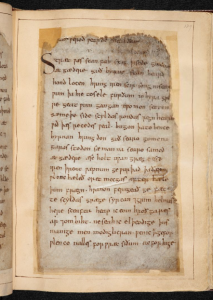

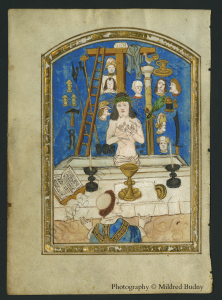

Budny Handlist 13

Although few in number, the fragments in the Handlist come from a varied range of types of texts, dates and places of origin, and modes of descent into modern times — not least through their dismembered reuse as binding materials of several kinds or for individual display as specimens of script, decoration, or illustration. Mostly they comprise single leaves (folia), pairs of conjoined leaves (folded bifolia), or scraps. Mostly they come with few, if any, indications of either their former ‘families’ within their original volumes and their former ‘homes’ in libraries or collections, or the identity of their despoilers. That is, apart from the clues which they carry upon their very surfaces or on materials which may have migrated with them, whether by chance or by design.

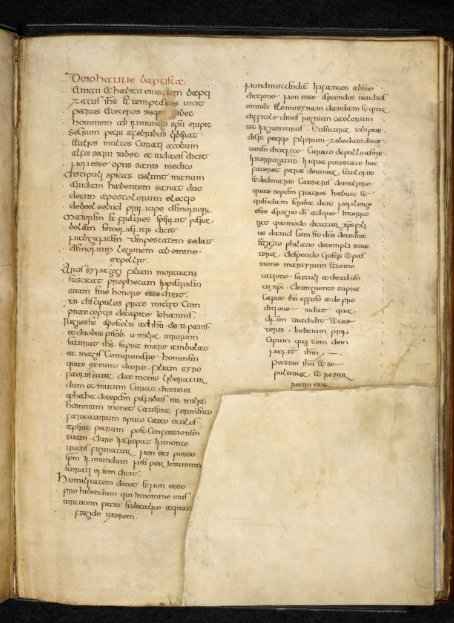

Those indicators, written or unwritten, may reveal their testimony principally in connection with the evidence preserved in other materials in other collections, provided that researchers might find it or learn about it. We have described and illustrated the interim results for one of the Handlist items recently (‘Handlist 13’, shown here), a detached 15th-century leaf with an intricate illustration on its verso of the Mass of Saint Gregory the Great, at which the celebrant of the Mass experiences a vision of Christ surrounded by the Instruments and Agents of the Passion.

The widespread dispersal, across the centuries and even — alas — nowadays, of scraps, leaves, or bits of manuscripts without regard, usually, to their complete original context within a whole manuscript, collection, or body of work by their given creator(s) can give rise to mixed feelings. The degree of mixture may depend upon the circumstances of dispersal or the disposition of the viewer, in various measures. On the one hand, the phenomenon constitutes a trashing of cultural heritage to be deplored. On the other, we might have some slender sense of relief that something, at least, has remained, if only by the skin of its teeth.

Following that toothy metaphor, we might lament or marvel, by turns or in combination, that any traces whatsoever might remain of past achievements, however down in the tooth, toothless, or plagued with perhaps ill-fitting artificial teeth they might now be. Let’s chew on that.

The Tips of Icebergs

In recent years, much attention in medieval manuscript studies (for example) has considered the despoliation, usually willful, of whole manuscripts so as to extract the juicy bits, such as illustrations, decoration, and choice specimens of script. Mostly without bothering to record their context and companions. Such practices have occurred across the centuries in many situations and for varied purposes, sometimes laudable.

The Magnificent, Despoiled,

Royal Bible of Saint Augustine’s Abbey, Canterbury

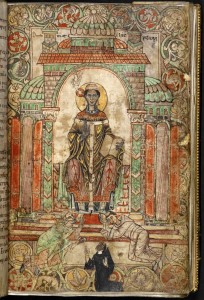

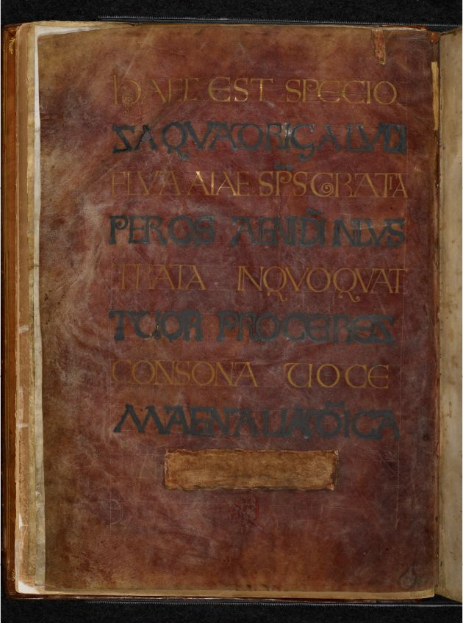

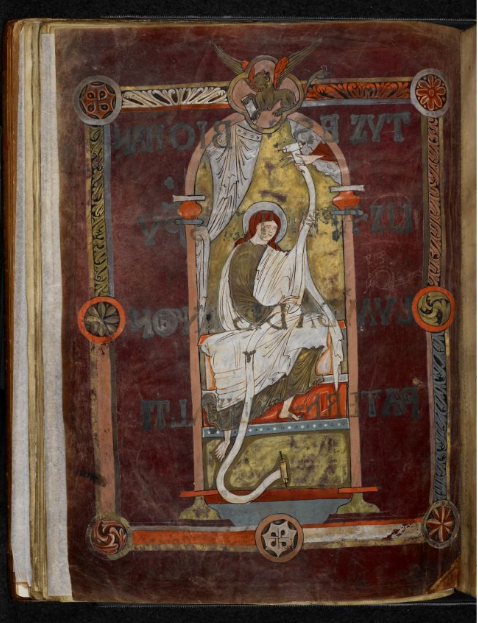

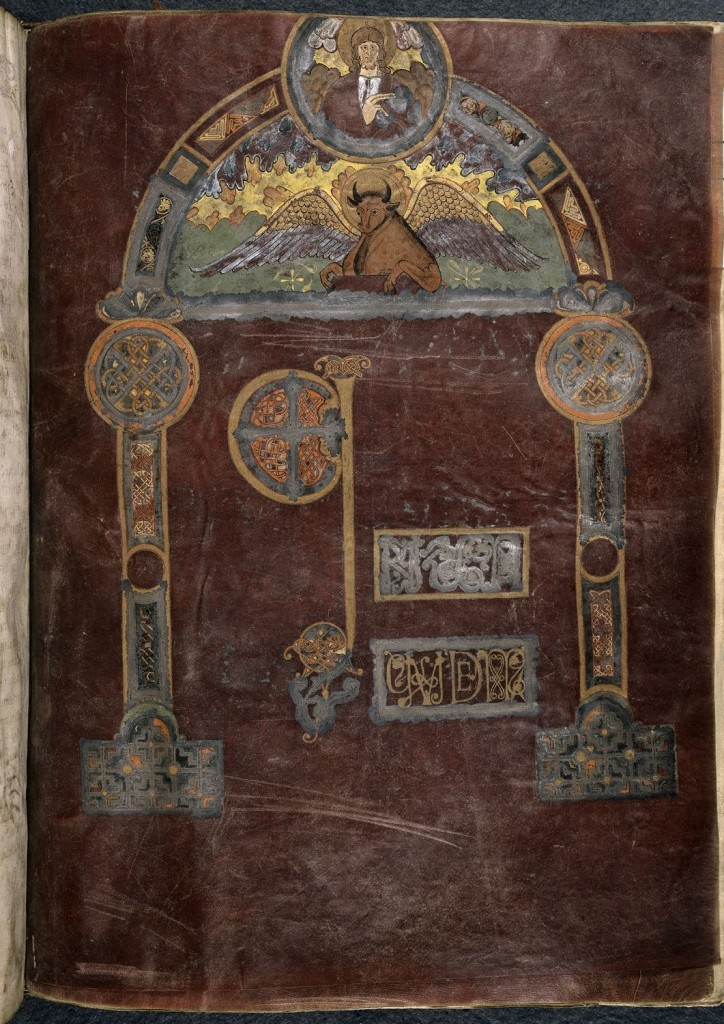

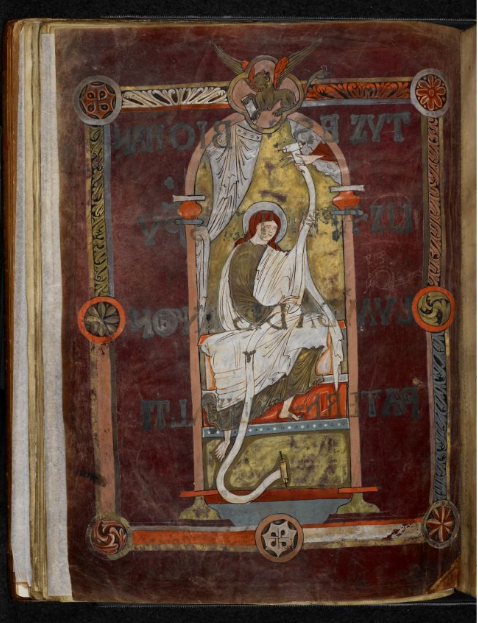

© The British Library Board, Royal MS 1 E.VI, folio 43r. Reproduced by permission

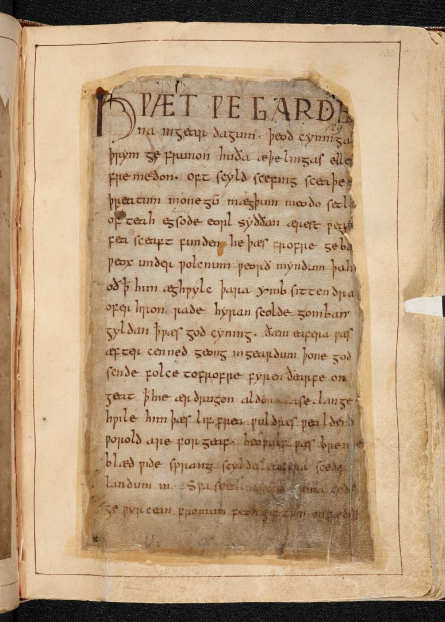

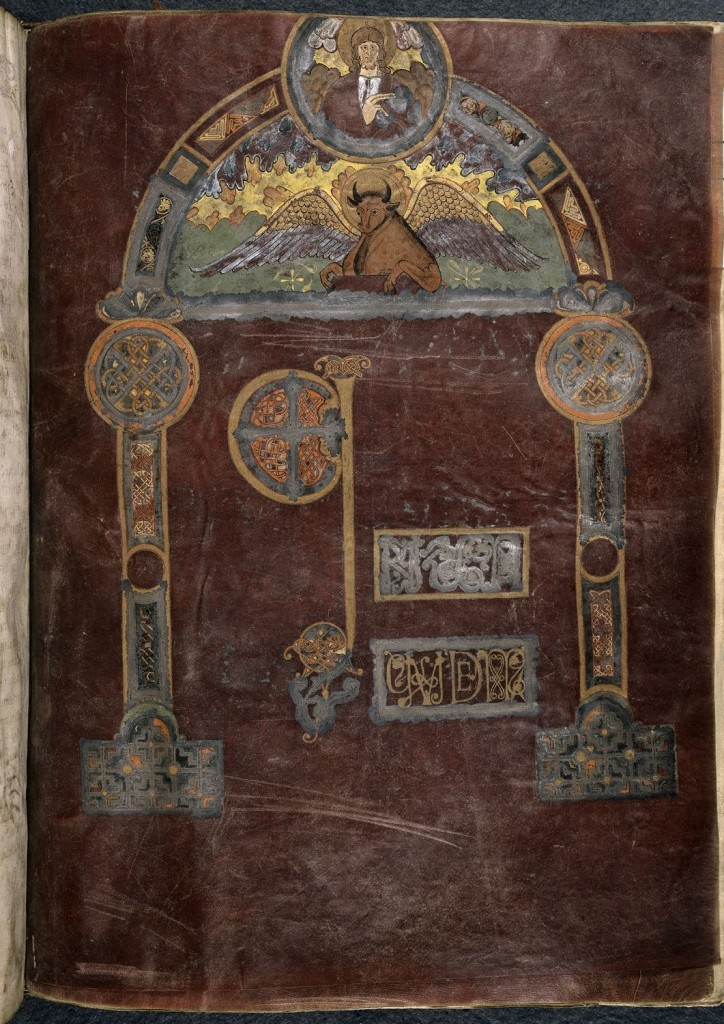

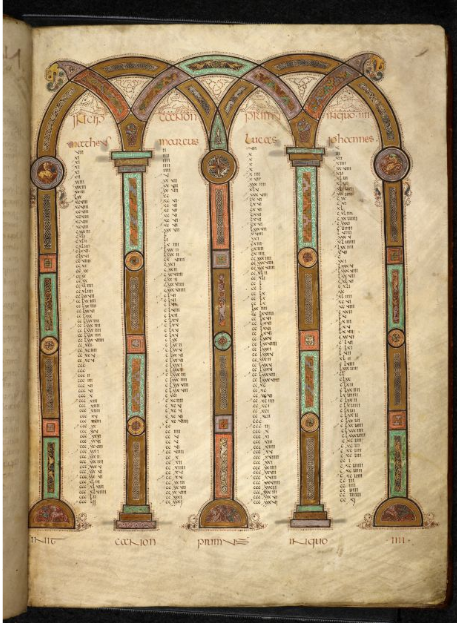

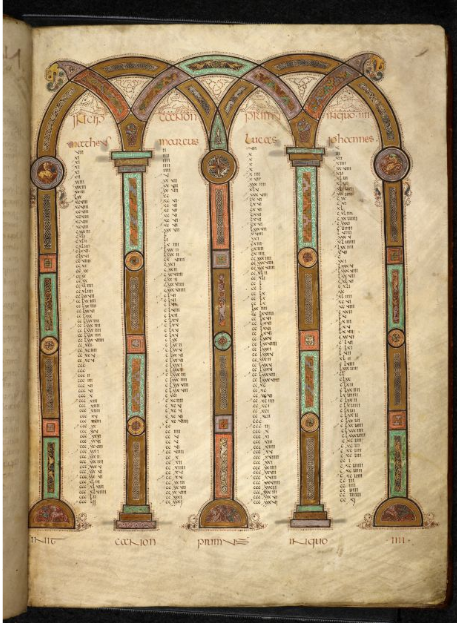

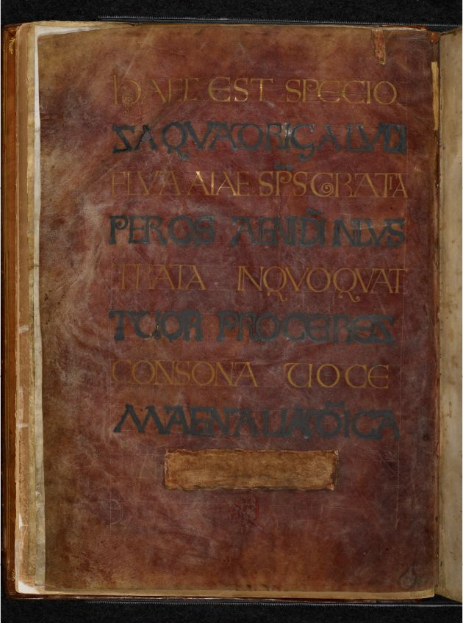

Years ago, in embarking on manuscript studies in earnest as a graduate student at University College London, I encountered this tendency, at a safe distance removed by centuries, in deciphering the evidence of the remnants of a superb manuscript made in the 9th century C.E. at St. Augustine’s Abbey, Canterbury. The manuscript contained a large-format copy of the full Vulgate Bible in Latin, with some prefatory texts and illustrations.Its remaining treasures include some richly purple-dyed leaves with full-page monumental inscriptions in gold and silver lettering and the majestic opening to the Gospel of Luke, which enshrines the intricately decorated opening words Quoniam quidem (‘Foreasmuch as’) within a full-page arcade with panels of ornamental interlace, geometrical, foliate, and animal patterns and with the half-length figures of both the evangelist’s symbol (a winged bull) and Christ holding books and appearing within heavenly clouds.

That monument, whose remnants survive mostly in London, British Library, Royal MS 1 E.vi, formed the subject of a detailed, holistic study, entitled ‘British Library Manuscript Royal 1 E. VI: The Anatomy of an Anglo-Saxon Bible Fragment’ (London, 1984), available freely online. Further discoveries about the manuscript and its astonishing Late-Antique model, the now-lost Biblia Gregoriana of the abbey, are reported here.

The process, progress, and discoveries of this cumulative work, demonstrating the value of a detailed, holistic study integrating multiple forms of evidence and fields of expertise, helped to lead to the formation and practices of the Research Group on Manuscript Evidence. Such fruits appear, for example, in the largest co-publication to date of the Research Group: the 2-volume Illustrated Catalogue of Insular, Anglo-Saxon, and Early Anglo-Norman Manuscript Art at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge.

© The British Library Board, Royal MS 1 E vi, folio 4r. Reproduced by permission

© The British Library Board, Royal MS 1 E vi, folio 28v. Reproduced by permission

Taking It Out

Why the medieval abbey — one of the principal centers of book-production in England — which had created so splendid a manuscript as the Royal Bible would choose to strip it of samples of illustrations and exemplary script within a mere two centuries of its creation (as the evidence establishes) remains a mystery, although there are some possible explanations. Explanations are not necessarily tenable justifications, of course.

By about the middle of the 11th century, some leaves and parts of leaves were cut from the manuscript at knifepoint, mostly with uneven cuts which appear to manifest disdain or haste — or both — in the process of excision. Thus were removed:

- numerous whole leaves with illustrations, leaving no gaps in the Bible text

- some frontispieces with illustrations for individual Books of the Bible (as with each of the four Gospels and the Gospel unit itself)

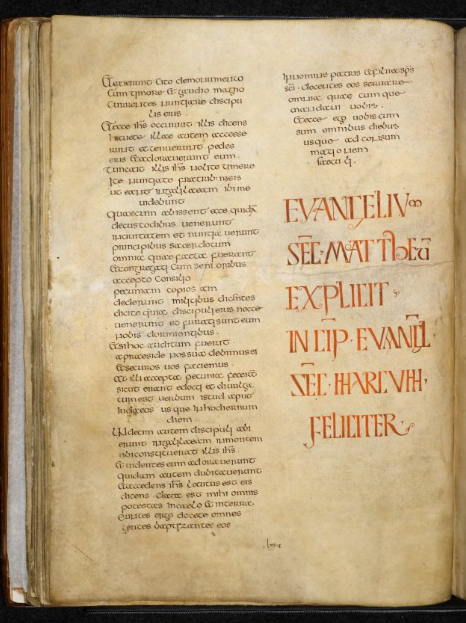

- some of the full-page monumental inscriptions which provided descriptive captions (tituli) for those illustrations (as with Matthew and John)

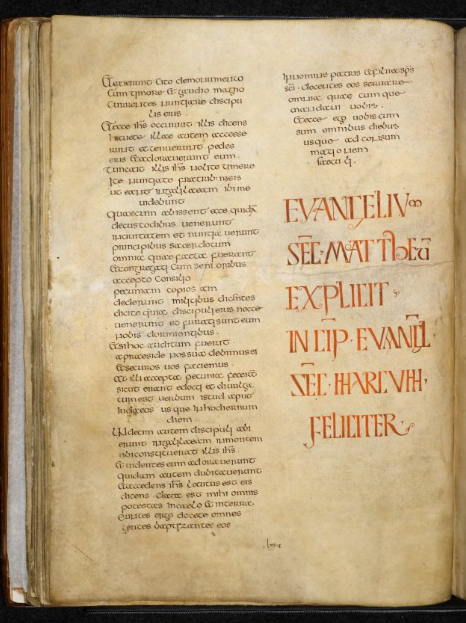

- some elaborate openings of Books of the Bible (as with the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and John)

- some specimens of one or more elaborate lines of script (as with the last line of the Gospel frontispiece titulus on folio 1 and the complete concluding titles for the Mark and John chapter lists on folios 29 and 69)

- and perhaps more sorts of elements.

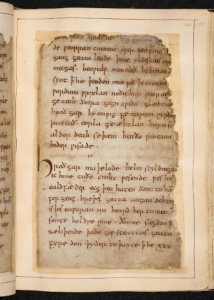

© The British Library Board, Royal MS 1 E vi, folio 29r. Reproduced by permission

© The British Library Board, Royal MS 1 E vi, folio 1v. Reproduced by permission

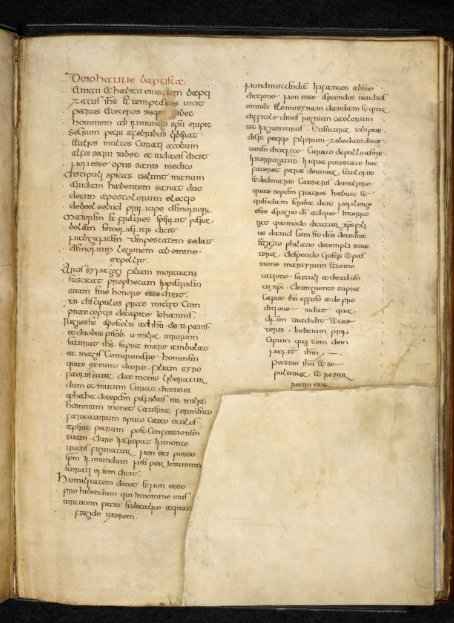

Some of those removed leaves or parts of leaves left offsets of their pigments on the pages which they formerly faced. Such are the case, for example, with the concluding title for the Mark chapter list and both the titulus and opening page for John.

Sometimes the removed portion introduced a gap within a leaf or at a lower corner of a leaf left behind. They occurred in excising specimens of elaborate script from it: taking the last line, in gold, from the descriptive titulus for the frontispiece to the Gospels (folio 1) and the elaborate concluding titles for the Mark and John chapter lists (folios 29 and 68).

The gaps were replaced with patches of parchment pasted onto the bare backs of the leaves. For a purple leaf, the patch was colored, somewhat inefficiently, with a pigment that has now faded to brown.

Taking Advantage, with Restorations of Sorts, in the 11th Century

© The British Library Board, Royal MS 1 E vi, folio 30v. Reproduced by permission

The cutting lines along part or all of some leaves adjacent to fully excised leaves, resulting from the slits of the knife drawn along the inner margin of the book, as the plunderer faced the wanted page, have been stitched together in a set of repairs following the spoliation and, it seems, following the retrieval of some of the fully severed leaves. For example, the leaf with the titulus for the Mark Gospel frontispiece (now folio 30) was completely severed, but it was resewn to its resulting ‘stub’. The following leaf received the same treatments, that is, severance by knife followed by reconnection with needle and thread.

© The British Library Board, Royal MS 1 E vi, folio 30v, detail. Reproduced by permission.

That this spoliation occurred by the mid-11th century or so is established by the white pigment overlay and overflow onto one of those stitching lines, along the inner margin of verso of that leaf which carries the Mark titulus on its recto. The overlying pigment belongs to the added frontispiece on the verso, which provides a framed frontispiece in a different style and with a different structure. In outlining the roundel at the bottom right of the paneled rectangular frame, the brush caught onto the repairing stitch, which tugged part of its tip and dragged some of the pigment, leaving the track which establishes the sequence of accretions. First came the cuts to excise leaves and parts of leaves. There followed the repairs to stitch some severed parts back into the book. Then came the addition of the painted frontispiece for the Mark Gospel, perhaps in an effort to refurbish the book, replace the lost Mark frontispiece in a new style, and/or try out an approach to painting on a purple-dyed leaf on an available expanse.

The artist of that Mark addition is identifiable as an artistic active in Canterbury, and at Saint Augustine’s Abbey, in about the mid-11th century. I have identified his work in some other manuscripts in my detailed long-term study. Among them are

Within the Royal Bible, in applying an outline of white pigment to the border roundel at the lower right-hand corner of the frame, his brush caught onto the stitching repair and left its traces there. Caught in the act.

Taking More, with Some Further Repairs, by the 14th Century

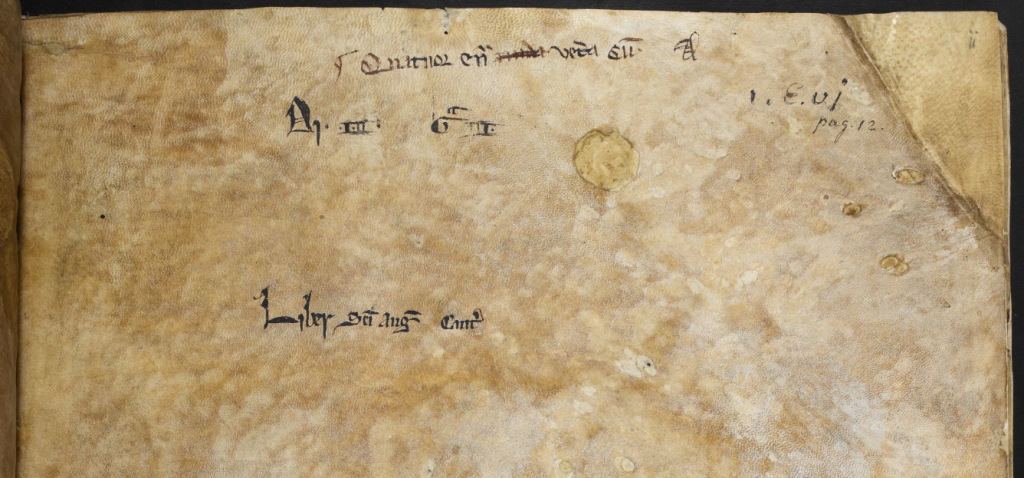

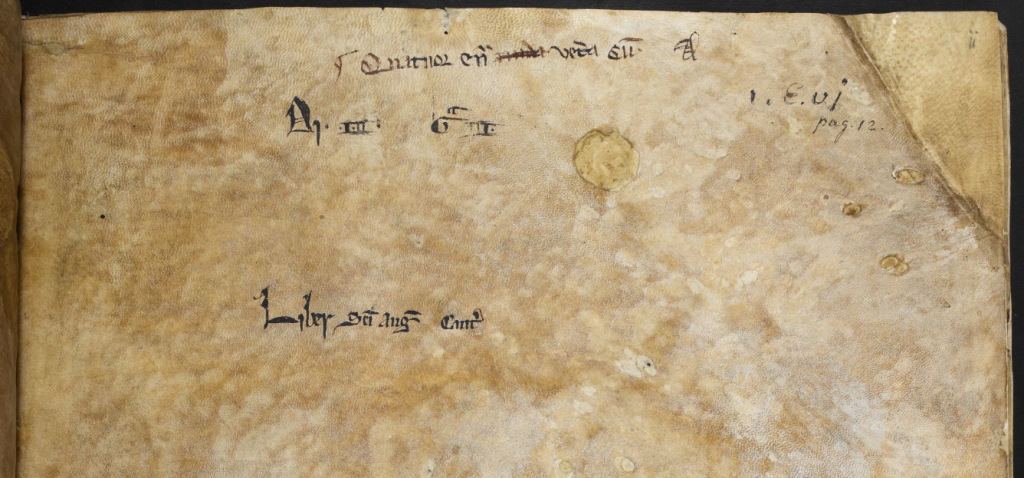

By the late Middle Ages, the manuscript had lost many more of its leaves — while still at the abbey — for reuse as binding material for other texts. Two of those reused leaves have surfaced at Canterbury Cathedral (as a folder for some unknown materials, removed from them without record in the 19th century) and in the Bodleian Library in Oxford (as a folded pair of endleaves for a 10th-century manuscript, removed from it in the 19th century). This form of despoilation of leaves for reuse in binding texts of other kinds occurred apparently by the 14th century. The forms of evidence which point to this date-range include the abbey librarian’s inscriptions, entered in stages at the top of one of the flyleaves added to the Royal portion by the 14th century. They provide the library ownership inscription, the library pressmark, and a brief description of the contents as an ‘old’ (vetera) and ‘bare’ or ‘despoiled’ (nuda) copy of the ‘4 Gospels with [the lettermark] A’. As on other books from the library, the lettermark stood on the binding (now lost in the rebinding at the British Museum in the 18th century). The rough parchment patches on the flyleaves, like the flyleaves themselves, belong to a recognizable stock of parchment leaves used for flyleaves, patches, and other work on the manuscripts in the abbey library during the 14th century.

Useful to know. And that knowledge about those tell-tale features of the parchment itself comes from having looked at very many of the many manuscripts which survive from the abbey library and show signs of refurbishment and other forms of alteration during this period (among others).

© The British Library Board, Royal MS 1 E vi, folio ii recto, top. Reproduced by permission

Altogether only 79 leaves remain of more than 1,000 leaves originally, plus the 2 endleaves added in the 14th-century to the front and back of the London portion, then reduced to a fragment of the Gospels. The Canterbury leaf, with its part from the John Gospel, formerly followed the last leaf in the Royal portion directly, as the first leaf of the next quire. Formerly placed at the distance of a few leaves from the Gospel portion, perhaps halfway through the quire after that, the Oxford leaf holds part of the Acts of the Apostles.

A small, but significant, remnant.

Competition

Few full Bibles survive from the Latin West up to the time of this 9th-century Royal Bible, and only one made in England: the early 8th-century Codex Amiatinus, but with fewer illustrations and less magnificent decoration. (No offense to that Bible, an astonishing witness in its own ways.) That somewhat distant relative, from Northumbria, and from the double monasteries of Monkwearmouth–Jarrow, home of the Venerable Bede (who may have had a hand in the production or design), helps to gauge the former stature of the monument, when complete.

The nearly contemporary Continental competition for our Royal Bible among large-format illustrated Carolingian Bibles or Spanish and other Bibles is another story. Have a look, for example at one of the earliest. These are big books, worth standing up to view them and, when chance arises, turn their pages.

‘The Ozymandias of Early Anglo-Saxon Book-Production’

About the Royal Bible, it is worth remembering that the despoiled carcass (shall we say) which remains of that vibrant whole, although dispersed between London (now with online facsimile), Canterbury, and Oxford, continues to bear witness to a former monument of extraordinary magnificence, albeit reduced to the floating tips of a once-weighty and mighty iceberg. Having worked to identify its significance as a precarious, but vigorous, witness, both to its original monument and to its majestic Late-Antique exemplar, the lost Biblia Gregoriana, I find some solace in the recognition by a sympathetic colleague, Richard Gameson (our Associate), that this 9th-century Royal Bible of St. Augustine’s Abbey, “still majestic despite truncation and mutilation,” might rightly be regarded as “the Ozymandias of early Anglo-Saxon book-production” (Royal Manuscripts: The Genius of Illumination (2011), no. 2).

In order words, this fractured, but still magnificent, monument must and can carry the weight of centuries. Fortunate it might be to find the opportunity, after all, to regain some of its eloquence. It is a privilege to spend time in its company, and I continue to remember, with affection, the very many days, months, and years on end of turning its pages, inspecting its details, learning to know its features, reflecting upon its character and contexts, and becoming familiar with its variety, complexity, and beauty as one of the most significant manuscripts of its age.

*****

And so now, with this case study freshly in mind, we turn to another group of ‘Lost and Foundlings’ among manuscript fragments, this time from dispersals of books from various centers, periods, types of texts, and styles of medieval book production, in ‘The Case of Otto F. Ege’, selfstyled ‘Biblioclast’. We invite you to have a look, as we unveil some newly recognized fragments among those dispersals.

A whimsical creature at the bottom of the page faces the music. Budny Handlist 4

A Virtual ‘Orphanage’

How the different ‘Foundlings’ among manuscript fragments might sometime find a proper, albeit virtual, home so as to acknowledge, to record, and to welcome their familial connections in former whole manuscripts as a form of ‘genealogical recovery’ remains to be determined in the concerted quest in various centers to establish and to foster such projects. While they find their fuller footing, with larger institutional supports, we will turn to the next report on our findings.

Next stop: ‘Lost and Foundlings’.

We welcome your comments, questions, and feedback. Please leave a comment or Contact Us.

*****

A Visit

A Visit A report of this December Visit appears as an Appendix to the “Preliminary Report” of the 15 January Workshop, printed and circulated as a Booklet after its event. A similar Report for the December Visit to the British Library appears in the Fifth, and Final, Annual Report to the Leverhulme Trust (1993–4) on the 5-year Research Project at The Parker Library on “The Archaeology of Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts” (Leverhulme Trust ref. F665). On the series of Annual Reports, see our Publications.

A report of this December Visit appears as an Appendix to the “Preliminary Report” of the 15 January Workshop, printed and circulated as a Booklet after its event. A similar Report for the December Visit to the British Library appears in the Fifth, and Final, Annual Report to the Leverhulme Trust (1993–4) on the 5-year Research Project at The Parker Library on “The Archaeology of Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts” (Leverhulme Trust ref. F665). On the series of Annual Reports, see our Publications.