Seminar on the Evidence of Manuscripts (11 December 1993)

September 16, 2016 in Manuscript Studies, Seminars on Manuscript Evidence, Uncategorized

“Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, MS 41: A Workshop”

Parker Library, 11 December 1993

In the Series of Seminars and Workshops on “The Evidence of Manuscripts”

The Parker Library, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge

2-page Invitation in pdf with 1-page RSVP Form

The previous Workshop in the Series considered

“Professionals’ Views of Manuscript Writing”

1 November 1993

[First published in 15 September 2016, as Mildred Budny reviews the event and its setting among the many events and activities of the Research Group on Manuscript Evidence]

*****

The Plan

Dated 12 November 1993, the 2-page Invitation Letter (shown here and downloadable here with the 1-page RSVP Form) provides the Menu for the Food for Thought.

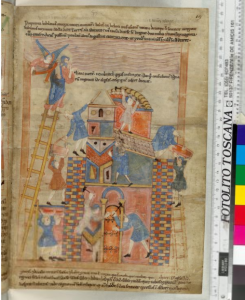

We plan to hold a workshop on Saturday, 11 December, devoted to Corpus Christi College, MS 41: the Corpus Old English Bede. This large-format eleventh-century manuscript principally contains a copy of the Old English version of Bede‘s Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum, with a large cycle of decorated initials, including historiated initials depicting secular and religious subjects. It also has numerous texts added in the margins and other available areas. In Latin and Old English, the additions include liturgical, homiletic, poetic and other texts: portions of a sacramentary, part of a martyrology, metrical and prose charms, a recipe, prayers, the beginning of Solomon and Saturn I, six anonymous homilies, two runic inscriptions and the bilingual donorship inscription recording Bishop Leofric‘s gift of the book to Exeter Cathedral. There are many trials, sketches and drawings, including some supplied, retouched or retraced initials. The multiple additions endow the book with the remarkable character of a combined “commonplace book” and sketchbook, forming a richly layered artifact.

Much goes on between the covers. Not all of it seemly. For example, this manuscript sees fit to include an image of a hanged man. Creepy.