Patched Repairs in ‘Otto Ege Manuscript 14’

With Pieces

of Text and Decoration

Extracted From the Same Manuscript

[Posted on 20 September 2020, with updates]

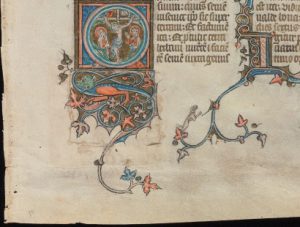

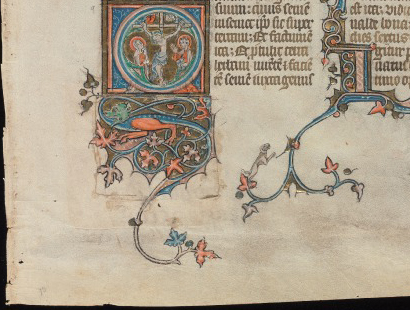

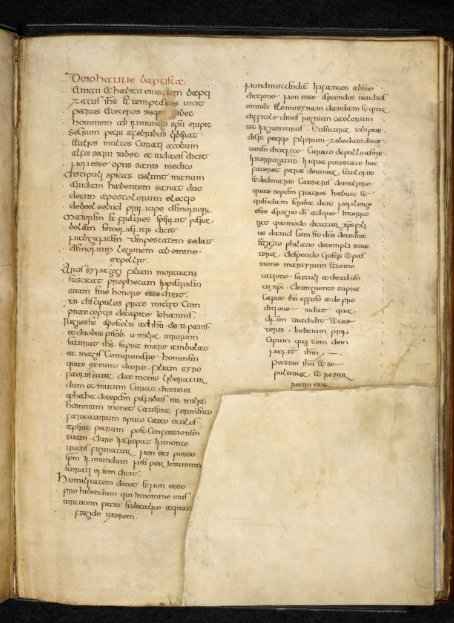

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, MS 14, Genesis Opening Leaf: Recto, Detail of Patch.

In a nutshell: Patches Work. Cut-Outs and Patches are recognized genres (sadly) in the history, transmission, plunder, and showcasing of medieval manuscript glories, plus efforts in some cases to cover the tracks.

Tracking those Traces? Call it Forensics. Detection Works.

Continuing our series of reports for some of the manuscripts dispersed by Otto F. Ege (1888–1951), we focus upon a little-recognized feature in one of them, which incorporates reused pieces from leaves in the same book for filling holes in other leaves. Previous accounts of the manuscript have taken scare notice of the feature; it could be more widespread in the book than their individual reported cases would indicate.

About this manuscript see, for example:

[And also now:

See also The Illustrated Handlist (Number 4).

We look forward to further publications about this manuscript by other scholars, including Joseph Bernaer and Peter Kidd. Joseph has kindly responded to our invitation to contribute his discoveries for publication, and Peter Kidd offers photographs which aid the quest. Peter’s publication of Volume 3 of \The McCarthy Collection: French Miniatures (forthcoming, 2020) is eagerly anticipated. [On this publication and its report of surviving illustrated portions of Ege Manuscript 14, see A Leaf in Dallas from ‘Otto Ege Manuscript 14″ (Lectern Bible).]

Patchwork

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, ‘Ege Family Album’, Leaf 14 verso, detail.

Some leaves of ‘Otto Ege Manuscript 14’ have patches which fill gaps made in excising decorative elements, presumably for display in their own rights as cuttings.

Many Western medieval manuscripts survive either with cuttings or from cuttings, which forcibly extracted portions of a leaf, resulting in a hole within its original expanse. Although very many of Ege’s leaves themselves constitute cuttings in the form of “whole leaves”, I distinguish these fragments from the related phenomenon of “snippets of decorated borders and isolated initials”, as described and illustrated from collections at the Victoria & Albert Museum, the British Library, and the Walters Art Museum.

So far as I know, studies of the manuscript and attempted reconstructions of the extant pieces of Ege Manuscript 14 do not take much account of the patches, apart from occasional mentions for some individual leaves.

While working to update an account of surviving parts of the manuscript, presented in More Discoveries for ‘Ege Manuscript 14’, I took care to inspect anew images of the leaves available for viewing online. In the process, I was struck by the references to patches on a couple of different leaves described by catalogue entries. Those references call for attention.

Their notices appears in 2 catalogue entries known to me. Both are “Rogue Leaves”, a term applied to some pieces of Ege’s manuscripts. That is, they were distributed otherwise than through the customary sets of Ege’s FOL Portfolio (Fifty Original Leaves from Western Medieval Manuscripts), in which specimens from Ege MS 14 — usually single leaves, but rarely a pair of leaves in a bifolium — were selected for Leaf Number 14.

An example, within its Ege mat:

The original manuscript is mostly known as Ege Manuscript 19 (Gwara, Handlist, No. 19, page 124). The numbering follows Ege’s numbering for his FOL Portfolio. Some identified parts are listed in Scott Gwara’s Handlist, by which we cite them here.

Via the Handlist

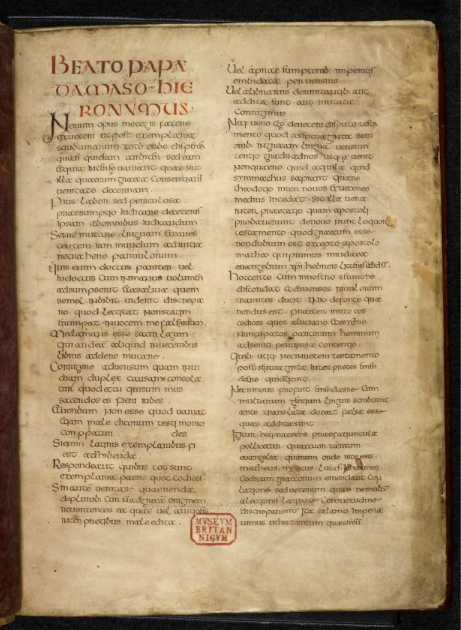

1. Gwara, Handlist 14.1.

Boston University = Judith H. Oliver, Manuscripts Sacred and Secular (1985), number 36 [but no plate]

- End of Kings, Prologue to I Chronicles, and beginning of I Chronicles,

with a ‘patch taken from another illuminated page of the same manuscript’ covering the cut-out from the ‘theft of initial for I Chronicles’.

One wonders which other page yielded its riches to patch up this leaf. (See below.)

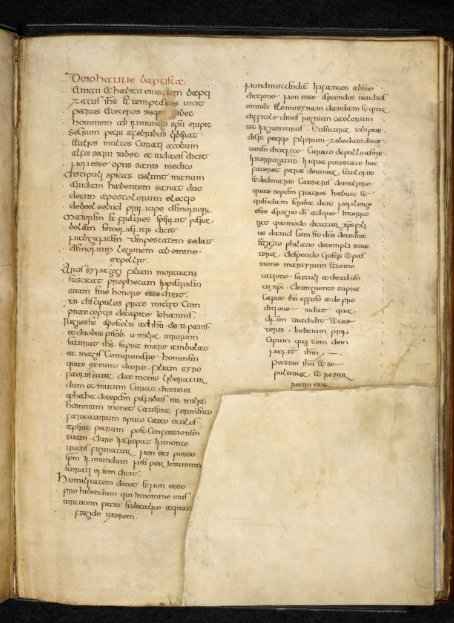

2. Gwara Handlist 14. Ref 14.

Sold at Sotheby’s 10 July 2012, lot 2(b)

The leaf carries the Opening of the Catholic Epistle of James on its verso; I have not seen an image of its recto (But see below and Update).

The leaf is described in the Sotheby’s catalogue thus:

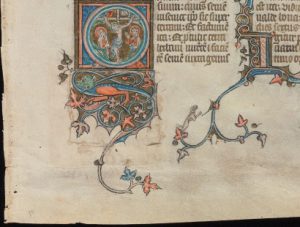

leaf from a lectern Bible, 400mm. by 270mm., with a large initial ‘I’ (opening “Iacobus ihesu christi seruus …”, the epistle of James) in burnished gold with a coloured architectural roof and arch, enclosing a bearded James with a golden halo pointing at the opening of his epistle, angular foliage forming text-frame around all sides of one text column, terminating in golden leaves and a dragon, 3-line initial enclosing ivy-leaf, similar text-frame on verso with a dragon and a 5-line initial containing a sprig of foliage ending with a dragon’s head, double column, 50 lines in a regular gothic hand, area of one column cut away (90mm. by 95mm., presumably once with a large initial), now repaired with another cutting from same volume [highlights added], once mounted on card with remains of tape on recto, France or southern Flanders, early fourteenth century

Its contents:

- Part of the Prologue to the Catholic Epistle of James (from [ut quia Petrus /] est primus in ordine apostolorum) and the opening of this Book, with 1:1–2:4 (nonne iudacitis [/ apud vosmet])

— plus a replacement patch with lines of script from 2 columns of text

Pasted to the recto of the leaf, on the verso the patch shows through the acquired hole, which functions as a form of ‘windowed mat’, across the end of column a and most of column b in their lines 25—37 on the damaged verso of the leaf. Viewed from the recto, the more-or-less rectangular patch, which has unevenly trimmed edges, can be seen to its full extent. Viewed from the verso, the extent and shape of the cut-out itself is known.

The mention of “remains of tape on recto” by which the leaf was “once mounted on card” shows that Ege’s matting turned the leaf front-to-back to display the verso. This is the same side as showcased in the Sotheby’s view online for its auction. The removal of part of the leaf presumably addressed an attractive historiated initial which began the Prologue on the recto.

The text on the patch identifies the leaf from which it was extracted in turn. (See below.)

[Update on 8 February 2022:

This leaf has returned to the market. The current online offering by Stephen Butler Rare Books & Manuscripts of Milton Keynes in the United Kingdom — via both the firm’s website (St James Preaching in an historiated initial on a leaf from a Bible in Latin [Paris, late 13th or early 14th century]) and AbeBooks — illustrates the leaf in two full-page views (recto and verso) and three details (initials and zoomorphic/foliate finials). The description reports travels from the 2012 Sotheby’s sale:

Sotheby’s, 10 July 2012, lot 2(b), the initial reproduced in colour in the catalogue; bought by: Robert Weaver, London; recently deaccessioned. Text: The main text is from Acts 27:40 to the end of Acts, a prologue to James (Stegmüller [Repertorium Biblicum Medii Aevi,] no. 809), and the start of James as far as James 2:4, but a portion of text has been cut out and replaced by a patch of parchment from the following leaf of the same manuscript, containing parts of James 2:10 3:9 and 4:8 5:20. This leaf both confirms that Acts appeared between Hebrews (the last of the Pauline Epistles) and James (the first of the Catholic Epistles), and that Acts had an historiated initial. . . . The parent manuscript is discussed, and the known leaves listed, by Peter Kidd, The McCarthy Collection, III: French Miniatures (London, 2021), no 60, pp.199 202, citing the present leaf on p. 201, no. 80, when still in the collection of Robert Weaver.

On that publication and its list of known illustrated leaves, see above and A Leaf in Dallas from ‘Otto Ege Manuscript 14″ (Lectern Bible). On the texts on the leaf and the patch, see below, reporting the fruits of study already from photographs kindly provided by Peter Kidd before the publication of his catalogue.]

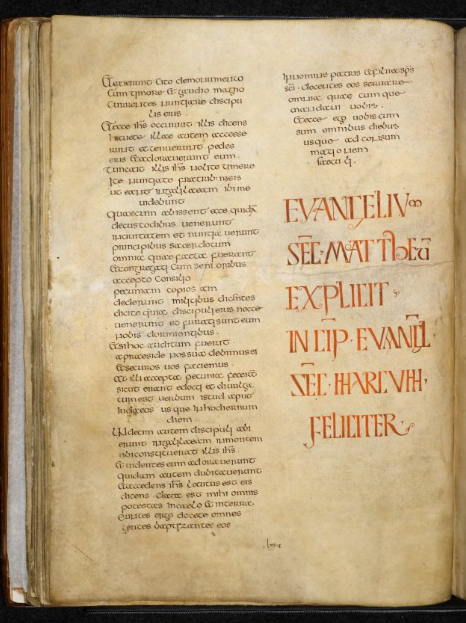

In the “Otto Ege Collection” now at Yale

Another case has emerged in the Otto Ege Collection. This “find-place” demonstrates that the patch was in place within Ege’s collection, not in some subsequent handling after it left his hands. That same chronological sequencing evidently pertains to other leaves from the same manuscript with similar patching.

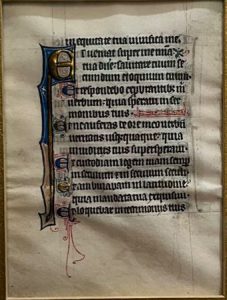

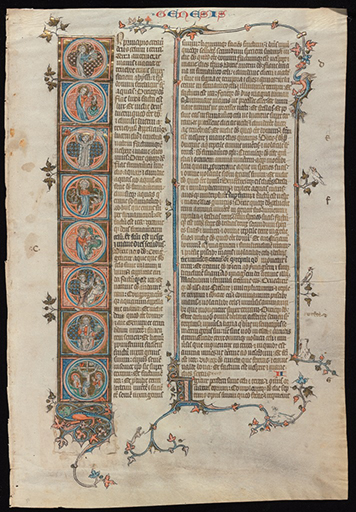

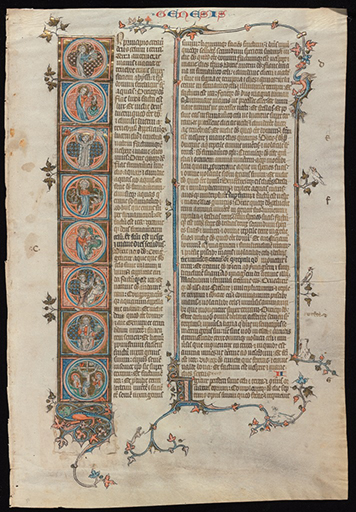

3. First leaf of Genesis

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection

Genesis opens with a full-page initial I (for Initium) and carries the text from Book 1:1 to 3

Recto

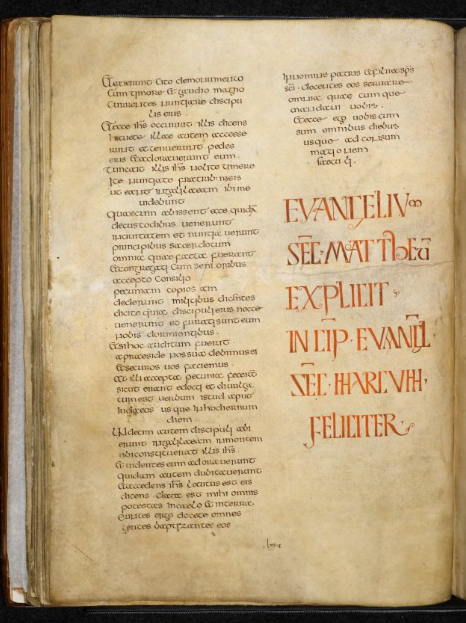

First page of Genesis from ‘Otto Ege MS 14’. Otto Ege Collection, Beinecke Manuscript and Rare Book Library, Yale University. Reproduced by permission.

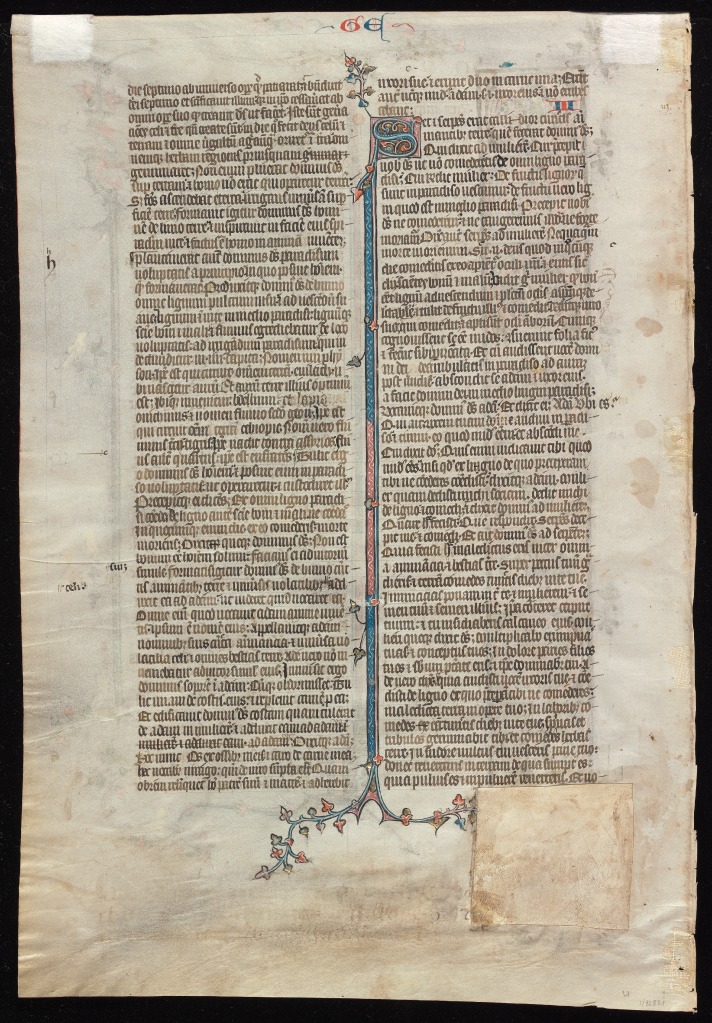

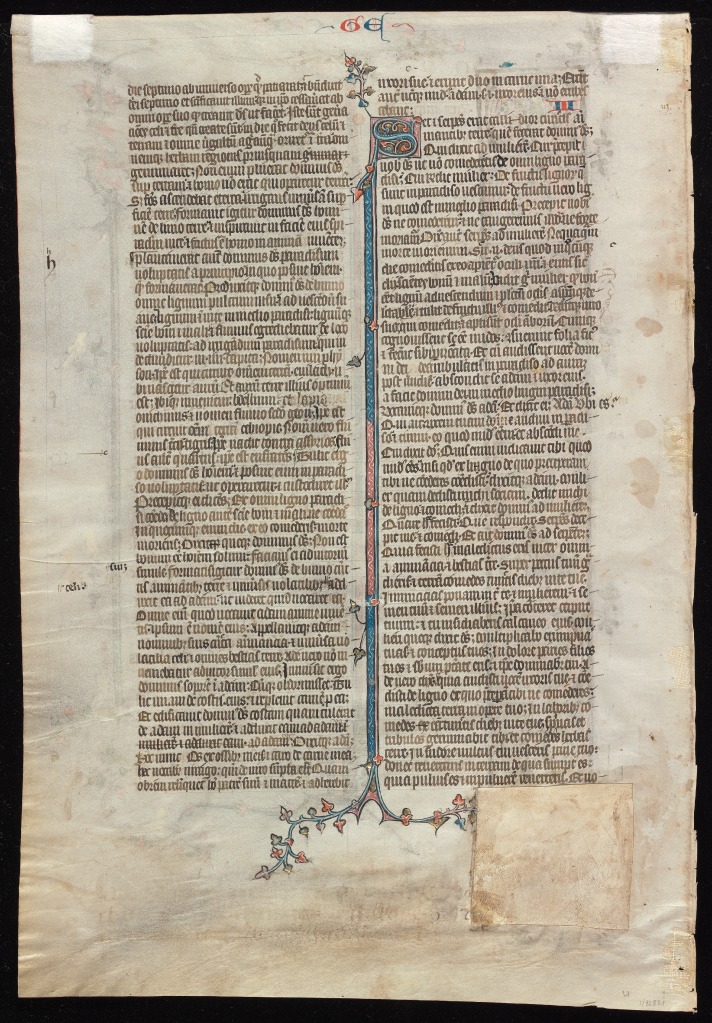

Verso

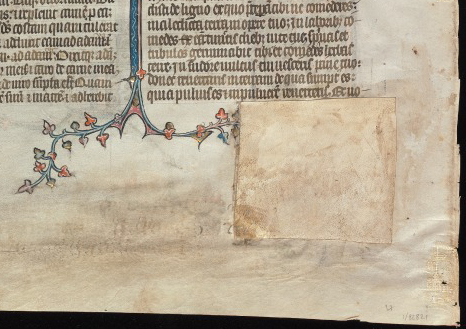

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, MS 14, Genesis Opening Leaf: Verso.

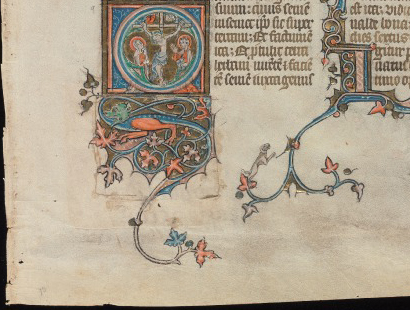

The Patched Repair

Recto

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, MS 14, Genesis Opening Leaf: Recto, Detail of Patch.

Verso

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, MS 14, Genesis Opening Leaf: Verso, Detail of Patch.

From Which Leaf?

Without (apparently) text on the patch to serve as a guide, it is uncertain to which leaf this decorated element belonged. At least, to judge by the animated decoration, with a dragonesque biped and branching, scrolling foliate tail, the element belonged to part of a major decorated initial.

The blank side of the patch could be suggestive. Can we know if originally the decorated element stood on a recto, with a blank verso, or the reverse?

As it now stands on the Genesis leaf, the decorated portion of the patch stands on the recto, with the blank side on the verso. If the pasted portion of the patch, hidden from view at the edges of the patch where it is pasted to the verso of the leaf, carries any text, the quest might become easier.

Might the hidden side of the patch itself, wherein the pasted parts of its ‘recto’ attach to the verso of the Genesis leaf, hold further clues in any other elements of script or decoration?

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, MS 14, Genesis Opening Leaf: Recto, Detail of Patch.

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, MS 14, Genesis Opening Leaf: Recto, Patch Rotated.

At present, in its patched position, the supplied decorative feature stands with the head of its dragonesque creature facing left with opened jaws. Seen in profile, the biped spreads both legs — appearing as hindlegs — in a striding pose, appearing to march forward, while its elaborate foliate tail creates a nest of branching, coiling scrolls below its body, plus an extension which descends into the lower margin. There, the tail branches again to form an opposed pair of foliate terminals.

On this side of the leaf, the patched portion neatly fits into the gap. The supplied segment with its creature nestles below the flat base of the initial I (for Initium). The letter comprises a vertical row of 8 block-like panels containing figural scenes illustrating episodes which culminate in the Crucifixion.

The tapering downward curve of the creature’s tail in the supplied portion appears to flow more-or-less seamlessly into an existing part of the decoration on the patched page, namely the downwards extension of a foliate strand which produces the pair of foliate terminals. Thus, the supplied patch and the existing decoration form a new, remedied, form of elaborate terminal for the full-page initial.

Who can say at present from which leaf came the patch? Might its decorative creature have stood in some other alignment on its original page (for example, as shown on the right)? That alternative, however, seems unlikely, given the orientations of similar decorative terminals to major initials in other parts of the book.

It is appropriate to wonder which major decorated element within the book was mostly ‘sacrificed’ for the sake of taking a patch from it. And what forms, perhaps, of damage which that element and its leaf had undergone already to be deemed to ‘merit’ such treatment. Relevant cases of significant damage could be, for example, the leaf near or at the front of the volume and now at Randolph College, with part of Jerome’s 2 Prologues to the Vulgate Bible.

The Patch for the “Sotheby Leaf” Sold on 10 July 2012

(Now in a Private Collection)

[Update: Full-page images of the leaf in color now appear online by its vendor, via both the firm’s website (St James Preaching in an historiated initial on a leaf from a Bible in Latin [Paris, late 13th or early 14th century]) and AbeBooks.]

Viewed from the Verso

On the verso of the Sotheby leaf from the opening of the Epistle to James — seen online via Sotheby’s 10 July 2012, lot 2(b) — the patch ‘fills in’ parts of 13 lines of text on the patched page. Pasted onto the recto, on the verso the patch supplies the right-hand side, or end, of column a and most of column b on the page, as it peeps through the irregularly-shaped ‘window’ cut into the leaf. In column b, the framed view of the patch covers most of the column between its line having mun-/tiam et habundantiam malitiae in man-[suetudine] of James 1:21 and its line with religio / Religio munda et immaculata apud deum et pa-/trem of James 1:27. The patch covers most of the lines in between, leaving visible the last few letters of the original column.

The patch provides the text of 13 lines from parts of 2 columns of text, presenting the narrow portion of a right-hand column and the wider portion of a left-hand column from some other leaf. Its own column b carries most of the lines of text from James 3:5 to to 3:9. Here I separate those transcribed lines into groups of 5, for convenience in keeping track of their span. Square brackets enclose the lost, or hidden, letters at the ends of lines, as spaced within the original column.

- Verso of Patch: Text in parts of 2 columns from the Catholic Epistle of James 2:8–12+ (in one column) and 3:5–9 (in the next)

Column b:

lines ‘1–5’

quidem membrum est, et magna ex[altat. Ecce]

quantus ignis quam ignis quam magnam [silvam incen-]

dit. Et lingua ignis est universitas [iniqui-]

tatis. Lingua constituitur in mem[bris nostris]

quae maculat totum corpus, et inflamm[at ro-]

lines ‘6–10’

tam nativitatis nostrae inflammata [a genen-]

na; Omnis eni natura bestia[rum et volu-]

crum et serpentium, et ceterorum do[mantur,]

et domita sunt a natura humana: li[-nguam]

autem nummus hominum domare potest: [?]

lines ’10–12′

inquitum malum, plena venendo [mortifer-]

o . In ipsa benedicimus Deum et Patrem [et in ipsa]

maledicimus homines, qui ad simili[tudinem . . . ]

The portions of column a on the patch show a few letters at the ends of lines of text apparently from James 2:8 to 12 and beyond. For example, starting opposite line ‘2’ of the column b of the patch:

Column a:

lines 2–5

[ . . . proximum tuum sicut teipsum bene facitis]: si au–

[tem personas accipitis, peccatum operam]ini, re–

[darguti a lege quasi transgressores] Quicum–

[que autem totam legem servaverit, offendat] autem in

lines 6–7

[uno, factus est omnium reus. Qui enim] dixit

[Non moechaberis, dixit et: Non occides. Qu]od si

[Etc.]

The other side of the patch would show the flow of text in its course either from or to these columns, so as to establish which side represents the original recto, and which the original verso. (See below.)

Rate of Text-per-Column or Text-per-Page on the Manuscript Leaf

Versus the Printed Vulgate Edition

However, even without seeing that side of the patch, estimating the rate of text-per-column which the script and layout of the Vulgate text customarily accomplished on its pages in the manuscript, apart from decorated initials of various sizes and opening or closing titles, allows for an educated guess as to where the patch would once have stood on its original page, and to which leaf it would have belonged.

The span of text missing between the bottom of the verso on the “Sotheby’s Leaf” (which ends within James 2:4) and the top of its inserted patch (beginning within James 3:5) amounts to some 3 columns of text as printed in a standard edition of the Latin Vulgate.

I chose as standard the “Weber” critical edition, also known as the “Stuttgart Vulgate”, edited by Robert Weber, Biblia Sacra iuxta Vulgatam versionem (Stuttgart, 2 volumes, 2nd revised edition, 1969), although that edition exists in later forms. My copy has served faithfully over the years since I purchased it in Dublin in the early years of my postgraduate research dedicated to a magnificent large-format Vulgate Bible manuscript, also despoiled, made in Canterbury in the 9th century and surviving in fragments in different places. That manuscript, too, has patched portions which remedy cut-out holes and corner-sections. (See below).

A note on available Vulgate editions (from Wikipedia, “Stuttgart Vulgate”):

In the Weber edition, like some other editions of the Vulgate version of the Bible, the double columns of text per page are laid out per cola et commata, as arranged by its translator Jerome. That is, the lines are set out in clause- and phrase-units, as an aid to readers, in accordance with long-standing tradition — rather than in continuous lines or paragraphs, as happens in Ege Manuscript 14. The printed pages have critical textual apparatus in the lower margin to report significant variants found in certain manuscript witnesses and some earlier printed editions. Note that the textual apparatus, reporting certain variants from the standard edition, can be useful in approaching late-medieval copies of the Vulgate, as I have found in examining portions of text in Ege Manuscript 14, including the ones here.

In Ege Manuscript 14, other cases of the rate-per-page can be seen on the first leaf of Genesis (also patched). Its recto, with a full-page initial at the left-hand-side of its column a, introduces that significant decorated variable or disruption in the standard rate. In contrast, its verso, without such major interruption or diversion within one of the columns, carries the text from Genesis 2:2 (et requirevit / de septimo ab universo) to within 3:19 (in pulverem reverteris et uo-[cavit Adam]). That span corresponds roughly to 3 1/2 columns of printed text (set out per cola et commata).

So, counting the rate of coverage in the manuscript, roughly 3 columns of text, as printed, would have stood between the “Sotheby’s Leaf” and the top of the patch on that leaf when still part of its own leaf. Which means the leaf following the Sotheby’s Leaf.

The patch extracted from James and 3:5 to 3:9 (on one of its sides) came conveniently from the very next leaf in the Bible; the recto of the patch served to remedy the recto of the cut-out portion on the restored leaf. The cutting from the Sotheby Leaf itself would have carried the decorated, and perhaps or probably historiated, initial on its recto.

Viewed from the Recto

And now, in a development for the unfolding research, Peter Kidd has kindly sent me a photograph of the recto of the Sotheby Leaf, now in a Private Collection, and photographs of both sides of the patched leaf in Boston University.

Sotheby Leaf

- Recto of Patch: Text in parts of 2 columns from the Catholic Epistle of James2:8–12(+) and 3:5–9

The Patched Leaf at Boston University

As described in Judith Oliver’s Catalogue of Manuscripts Sacred and Secular (1985), the leaf with a patch at Boston University has the

- End of Kings, Prologue to I Chronicles, and beginning of I Chronicles (as above)

It is now possible to refine the description, with thanks to Peter Kidd’s photographs.

The leaf is Boston University, School of Theology Library, MS Leaf 38. The leaf itself contains, albeit with gaps front and back from the cut-out section:

- the end of IV Kings 25:17 [cubitor altitudinis/] habeat columna) to the end (verso 30),

- the text of Jerome’s Prologue to Paralipomenon (Chronicles) [however numbered as XXVI in the margin], including the decorated initial S of Si, and

- the beginning of I Chronicles to 1:41 (Dison filii [/ Dison Amaran]), but without the decorated initial of the Book and parts of its column b (cut out and lost)

On the verso, seen in full, the patch covers part of column a, between the last few lines of the Prologue, following the words ipsi et / meis iuxta], and the first lines of Book 1 up to the last line of the column, preceding [Rif-]ath et Thorgorma filii autem Ie[-van Elisa].

The Patch carries portions of text from the same Catholic Epistle. The framed recto of the patch shows 12 lines of text, while the full, unframed, extent of the verso shows 14 lines. Seen in full, the verso demonstrates that the patch came from the bottom of its column, as it retains not only the last line of text but also the upper portion of the lower margin (some 2 lines’ worth of space), including parts of the foliate ornament of the lower terminal descending from the vertical band which frames the left-hand-side of the column. The expanse of margin at the left beyond that border bar demonstrates that the column stood at the left in the pair of columns on its original page, and not in the narrower intercolumn between the pair.

- Recto of Patch: Catholic Epistle of James 3:17 ([sucedib-/il[is] bonis consentiens) to 4:4 (est Deo Quicum[/-que ergo]), including the opening initial U of Unde for Chapter 4

- Verso of Patch: Catholic Epistle of James 5:4 ([uestras qui] fraudata est) to 5:10 (patientiae prophetas [quo locuti])

Note: The reading sucedibilis + bonis consentiens in James 3:17 corresponds to a variant attested in some other witnesses, shown in the textual apparatus for the Weber edition (1975), volume II, page 1862.

The Source Leaves

The gap in text between Patch ‘1’ from the Epistle of James and Patch ‘2’ — that is, the text between James 3:9 and 3:17 — amounts to roughly 3/4 of a printed column in the Weber edition.

It appears that the patch on the Boston University Leaf may have come from the same leaf as the one sacrificed to patch the ‘Sotheby Leaf’.

We might presume that the work of patching both these leaves belonged to a single operation. Perhaps the patch for the Genesis opening leaf now at Yale likewise belongs to the same operation?

Styles of Cutting and Styles of Patching

It might be true that “A Rose is a Rose is a Rose”. But the same does not pertain to “A Patch is a Patch is a Patch”. Patches in medieval manuscripts come in many different shapes and sizes, and their styles of application vary, too.

Exhibit A

The 9th-century Royal Bible of Saint Augustine’s Abbey, Canterbury: London, British Library, Royal MS 1 E. vi., available for view in a digital facsimile. It is the subject of my Ph. D. dissertation, “British Library Manuscript Royal 1 E.vi: The Anatomy of an Anglo-Saxon Bible Fragment” (University of London, 1985), published online.

The large-format Vulgate Bible has been reduced to a fragment of its former splendor. Originally a Bible of some 1,000 leaves in large format, it has lost very many leaves, as well as some part-leaves. At least some of them were apparently severed at knife-point for elements of illustration, decoration, and decorated text. The losses belonged to more than one campaign of spoliation, which took place apparently at the home of the manuscript in the medieval period, Saint Augustine’s Abbey.

Here we consider the surviving patches, of uncertain date, which inelegantly fill the gaps introduced when portions of decorated script were cut out, perhaps to serve as specimens.

Patches adhere to 3 surviving leaves. Each patched leaf has decorated text on its recto, while the verso was originally blank.

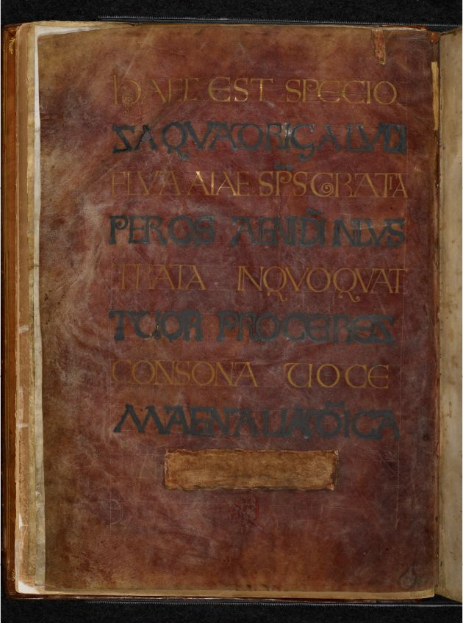

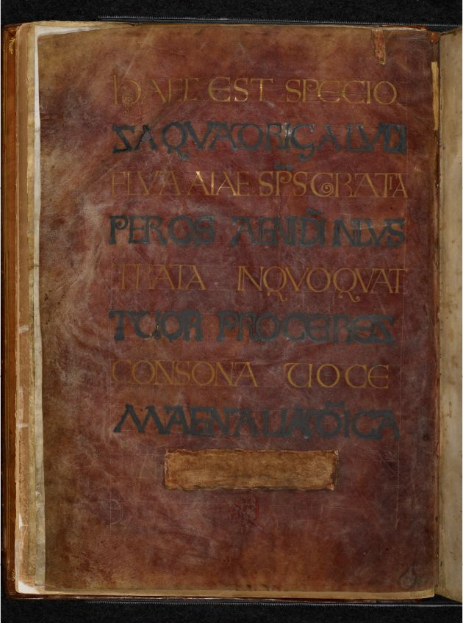

Folio 1

Folio 1 at the front of the Gospel or New Testament unit is a purple-dyed leaf written in lines of monumental capitals which alternate between lines of gold and (oxidized) silver pigment. The centered last line of the inscription was cut out at some stage; presumably its letters were gold. Its gap was filled with a stained and now darkened patch pasted to one side.

The process of cutting involved drawing the point of a knife along the surface of the leaf while it lay against the following leaves. The cutting mark incised a corresponding flap in folio 2; the severed lines were stitched back into place.

© The British Library Board, Royal MS 1 E vi, folio 1v. Reproduced by permission

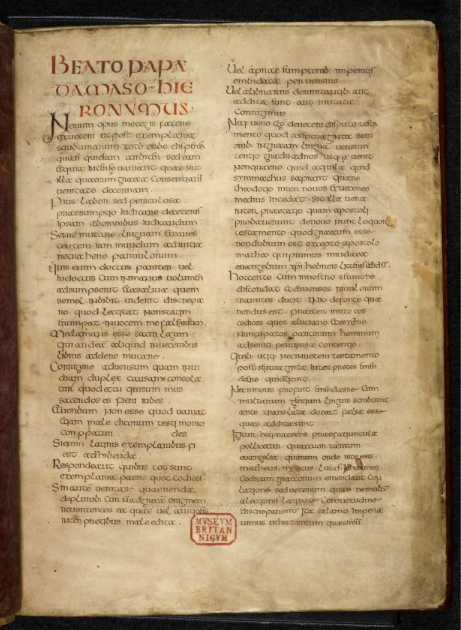

The next leaf has a stitched repair for the cut-out flap which resulted from the drawing of the knife point against the sought-after recto of the preceding folio while the book lay open. The stitching is visible just above the British Museum stamp centered below the columns of text.

© The British Library Board. Royal MS 1 E VI, folio 2r.

Folio 28 (with a Patch similar to Folio 68)

The unevenly cut-out lower outer corner of the leaf with the Chapter List for the Mark Gospel was filled with an unevenly trimmed patch, similar to the patched repair on the John Chapter List. In both cases, the Chapter List occupies the recto of the leaf; the verso is blank. Presumably the tapered text of column b led to an embellished element of some kind, for which the excision was effected. The patch is pasted to the verso.

Recto

© The British Library Board, Royal MS 1 E vi, folio 29r. Reproduced by permission

Verso of Patch

On the back, the full extent of the patch shows itself.

© The British Library Board. Royal MS 1 E VI, folio 68v, detail. Verso of patch.

An Example of the Decorated Titles

© The British Library Board, Royal MS 1 E vi, folio 28v. Reproduced by permission

The patches at least fill gaps on the leaves of the Bible, but their function solely replaces pieces of parchment. In the case of Folio 1, the patch offers an attempt to colorize the patch, so as to try to match or mask the purple-dyed original leaf. Over time, the color on the patch has faded or changed to brown, revealing its different stage in the non-original work on the manuscript.

Cuttings Galore

Specimens of cut-outs, once they are extracted from their original books, sometimes gather in collections dedicated to specific dates, regions (say, Italy), and types of decoration. For example, The British Library’s collection of Italian illuminated cuttings. Described thus:

The British Library’s collection of Italian illuminated cuttings consists of around 675 initials, miniatures, and single leaves. These were predominantly cut from liturgical manuscripts of northern and central Italian monasteries and churches that were suppressed in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Cuttings from non-religious manuscripts, such as miniatures from law text-books, and frontispieces from doge’s commissions of the Venetian Republic, are also represented in the collection.

The Victoria & Albert Museum has many such specimens, besides its collection of manuscripts. The range is summarized thus:

The National Art Library at the V&A holds over 300 Western illuminated manuscripts dating from the 11th to the early 20th century, including books of hours, bibles, missals, choir books, classical works, patents of nobility, and grants of arms and illuminated addresses.

In addition to these, the museum’s collections also include about 2,500 manuscript cuttings representative of different styles, periods and regions. While a few Islamic and Ethiopian manuscripts are held in the National Art Library, most of the non-Western material is part of the museum’s Asian collections.

Etc. Somewhere, perchance, the cuttings from Ege Manuscript 14 might survive, awaiting discovery. Perchance might the leaves from which the patches were extracted also survive?

The Extant Patches in Ege Manuscript 14 as Cuttings

and Its Extant Leaves with Cut-Outs

So far, we know of no extant leaves from Ege Manuscript 14 which have holes left-over from decorated elements cut out from them, say in the form of cuttings for display on their own.

Perhaps it is worth considering scrapbooks or collections of cuttings as possible locations for dispersed parts of the book. Peter Kidd’s website for Medieval Manuscripts Provenance reports admirable cumulative research on these subjects.

Are we in a position to know when the cuttings were extracted from Ege Manuscript 14? All at once? Neither of the sales catalogues which showcased the manuscript while still intact, at Sothebys in 1936 and at Parke Bernet in 1948, mention such cuttings, nor such repairs. Does that omission indicate an unremarked or unmentioned feature, or did the cut-outs exit later? Are we certain that the sale in 1948 went directly to Ege, or instead to some intermediary?

Clues toward the ‘workshop’ which patched the cuttings might reside in the ‘style’ of patch work. That is, the choices of patches and their methods of placement and positioning upon the leaves exhibit an elevated degree of attention to design and layout.

The recto of the patched Sotheby’s leaf shows pencil markings in the form of arrows which guide the placement of the patch to fit within the ‘window’ of the hole. See its image: Sotheby’s 10 July 2012, lot 2(b) . Might we guess whose marks are these?

More research on the fragments of Ege Manuscript 14, as more become visible to study, may help to answer such questions. They may, for example, reveal further aspects of Ege’s workshop practices in dismembering his manuscripts or other books and presenting them for display and distribution.

Contributions to that research is presented on our blog. For example:

*****

Do you know of other patched leaves in this manuscript? Do you know of cuttings from it?

Please let us know.

Add your Comments here, Contact Us, and visit our Facebook Page.

Watch this space and follow our blog for further research on dispersed manuscripts, those of Otto Ege included. See the Contents List.

*****