Knowledge Games and Games of Knowledge: An RGME Session for IMC 2025

August 13, 2024 in Announcements, Call for Papers, Conference, Events, International Medieval Congress, Leeds, Manuscript Studies

Call for Papers

“Knowledge Games and Games of Knowledge:

A Global Perspective on

How Manuscripts Conserve and Transmit Ludic Knowledge”

Session

Sponsored by the RGME

IMC Leeds 2025

Organised by Michael A. Conrad

(University of Sankt-Gallen)

[Posted on 13 August 2024]

Following the success of our Inaugural Session at the International Medieval Congress this year, the Research Group on Manuscript Evidence announces its proposed Sessions for the International Medieval Congress to be held at the University of Leeds from 1–10 July 2025.

Paris, Musée Carnavalet, Projet pour le Pont Neuf, circa 1577. Image via Wikimedia via Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported.

Background: 2024

Our 2024 Inaugural Session, co-organised by our Associates Ann Pascoe-van Zyl and Michael Allman Conrad, focused on “Building Bridges ‘Over Troubled Waters'”:

Foreground: 2025

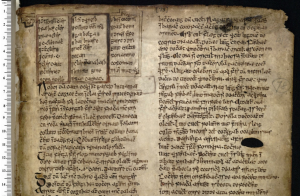

Dublin, Royal Irish Academy, MS 23 E 25, p. 73, top. Image via https://codecs.vanhamel.nl/Dublin,_Royal_Irish_Academy,_MS_23_E_25 via Creative Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

For 2025,with the IMC’s Thematic focus of “Worlds of Learning”, the RGME proposes an integrated suite of events comprising a pair of Sessions of papers plus a Roundtable discussion on “Manuscripts as Worlds of Learning”.

In addition, following up on a strand in our 2024 Inaugural Session, the RGME also proposes a sponsored session organised by that session’s co-organizer and presenter, Michael Allman Conrad.

The Plan for the Session

“Knowledge Games and Games of Knowledge:

A Global Perspective on

How Manuscripts Conserve and Transmit

Ludic Knowledge”

Recent scholarship has pointed out time and again how much in the Middle Ages games and other joyful pastimes were not only cherished and accepted as an essential part of everyday life, but also well appreciated as educational tools for making difficult lessons more palatable for students.

Some of these educational games have a long tradition, such as rithmomachia, which was used in schools for instruction in the quadrivial arts and still known by scholars of the 17th century. Some disciplines, such as astronomy, even had their own games — in this case, for example, the ludus astrologicus. The knowledge of such elaborate games was transmitted through manuscripts, often as part of miscellanies. Besides, there is no lack of writings dedicated to more profane games either. In fact, there are collections of board games (and other pastimes), with some of these manuscripts showing very rich and ornate embellishments and game diagrams, along with vivid miniatures depicting players in action.

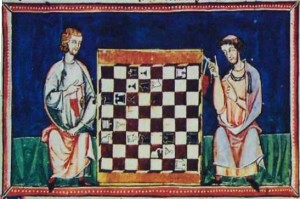

Madrid, Real Biblioteca del Monasterio de El Escorial, MS T-I-6, folio 27 verso. Image in the Public Domain, Via Wikipedia Commons.

Examples of such works include

- the Book of Games (Libro de acedrez dados e tablas c. 1284) by Alfonso X of Castile, in the Bonus Socius group (13th century?),

- the Paris manuscript of Le jeu de echecs by Nicola de S. Nicholai (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France (BNF), MS fr. 1173, 14th century),

- as well as lesser-known manuscripts, such as Cambridge, Trinity College, MS O 2.45 (after 1248 AD).

The book medium, however, poses serious challenges to scribes concerned with conserving and conveying knowledge related to games and other pastimes, as their existence is ephemeral and their experience difficult to verbalize — which is a reason why in the (Arabic and European) tradition medieval books on games usually came with said pictures and diagrams, with the intent to compensate for what cannot be easily expressed through words alone. What is more, in medieval writings on games their epistemological status often remains ambivalent and uncertain, as they were often touted as morally ambiguous and did not fit existing knowledge systems. That said, there nonetheless were some scholars that tried to fit ludic knowledge into prevalent eschatological framework of knowledge, such as Hugh of Saint-Victor, with some of them basing their (re-)assessments of the morality and epistemic status of games and other forms of entertainment on Arabic and Greek influences. As reaffirmed by Hugh and in the work of Thomas Aquinas, the Latin concept of ludus could not only serve as an umbrella term for various kinds of games, but all forms of entertainment.

While the focus of the proposed Session is games, the evocation of ludic knowledge is intended as an invitation to different kinds of pastimes in order jointly to examine how medieval scholars dealt with game-related forms of knowledge, from material objects to their metaphysical and anthropological relevance. Especially the latter implies and extends the perspective towards practices employing games and other pastimes methodologically for educational purposes. Consequently, the geographical scope is not restricted to the European sphere. On the contrary, since there is strong evidence that European game manuscripts drew much from Arabic and other non-Latin traditions, contributors focusing on the Byzantine Empire, the Islamic world, India, or other cultural world regions are very much welcome and encouraged to partake.

Some possible questions could be (but are not limited to):

- What do we know about the authorship of game manuscripts?

- Are the works written by single individuals or collectives?

- In what types of miscellanies do writings on games and game manuals appear and why?

- How do manuscripts/authors deal with ephemeral aspects of games and other pastimes that are difficult to be expressed linguistically?

- How can we reconstruct the concrete educational practices wherein games and other pastimes were used?

- What hints thereof can we find in the material evidence of manuscripts?

- How do authors try to systematize ludic knowledge and where do they position it within given epistemic frameworks?

- What can we say about the relationship between game diagrams and diagrammatic representations in scientific disciplines in terms of a shared visual vocabulary?

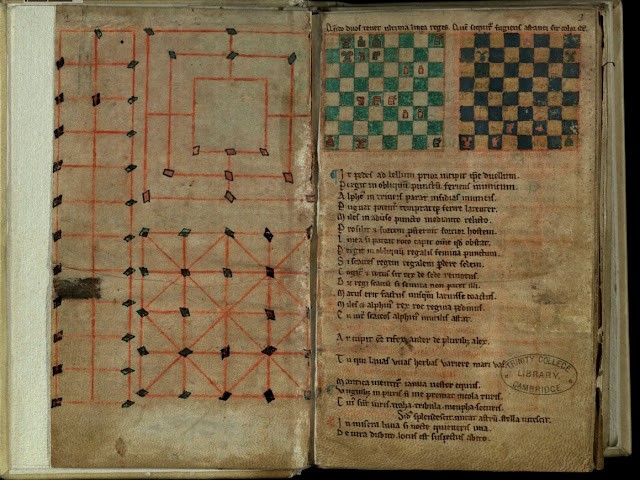

Cambridge, Trinity College, MS O.2.45, fols 2v-3r. Image copyright the Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge, via CC-NY 4.0.

Note on the Image

Cambridge, Trinity College, MS O 2.45 (after 1248 AD), folios 2v and 3r. Accompanying the text, diagrams and illustrations depict two chess boards, an alquerque, a nine-mens-morris and a daldøsa game board. The first moves of the game are already played.

Image © the Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge, via License CC BY-NC 4.0 via Trinity College Cambridge.

Proposals

For information about submitting your proposals for our Sessions, please see the CFP for our companion suite for IMC 2025:

Deadlines for Proposals

- 5 September 2024 for your individual paper proposals for our RGME Sessions and Round-table Discussion

- 30 September 2024 for the RGME to complete and submit its programmes.

To prepare your proposals, see the IMC instructions

Send your proposals for our Session to us at

- rgme.imc.sessions@gmail.com by 5 September 2024

When your proposals are accepted, we will direct you to submit them through the

Spread the Word

Look for our RGME CFPs on the IMC 2025 website:

- IMC 2025 Padlet Page

Questions and Suggestions?

If you wish, please:

- add your Comments here,

- send us a message (Contact Us),

- visit our Facebook Page and Facebook Group,

- join the Friends of the Research Group on Manuscript Evidence (there is no charge), and

- register for our events on our RGME Eventbrite Portal:

RGME Eventbrite Collection

*****