Another Leaf from the Warburg Missal (‘Ege Manuscript 22’)

April 25, 2021 in Manuscript Studies, Reports

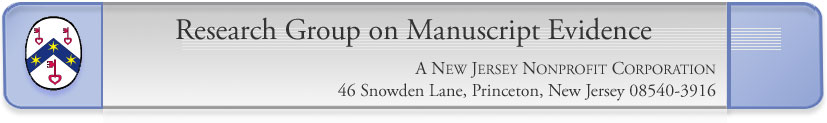

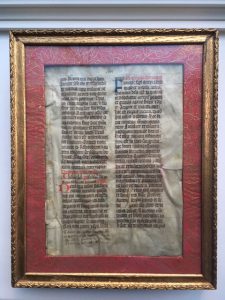

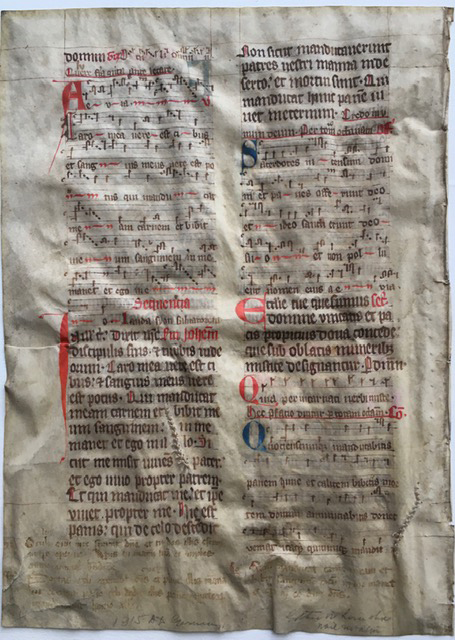

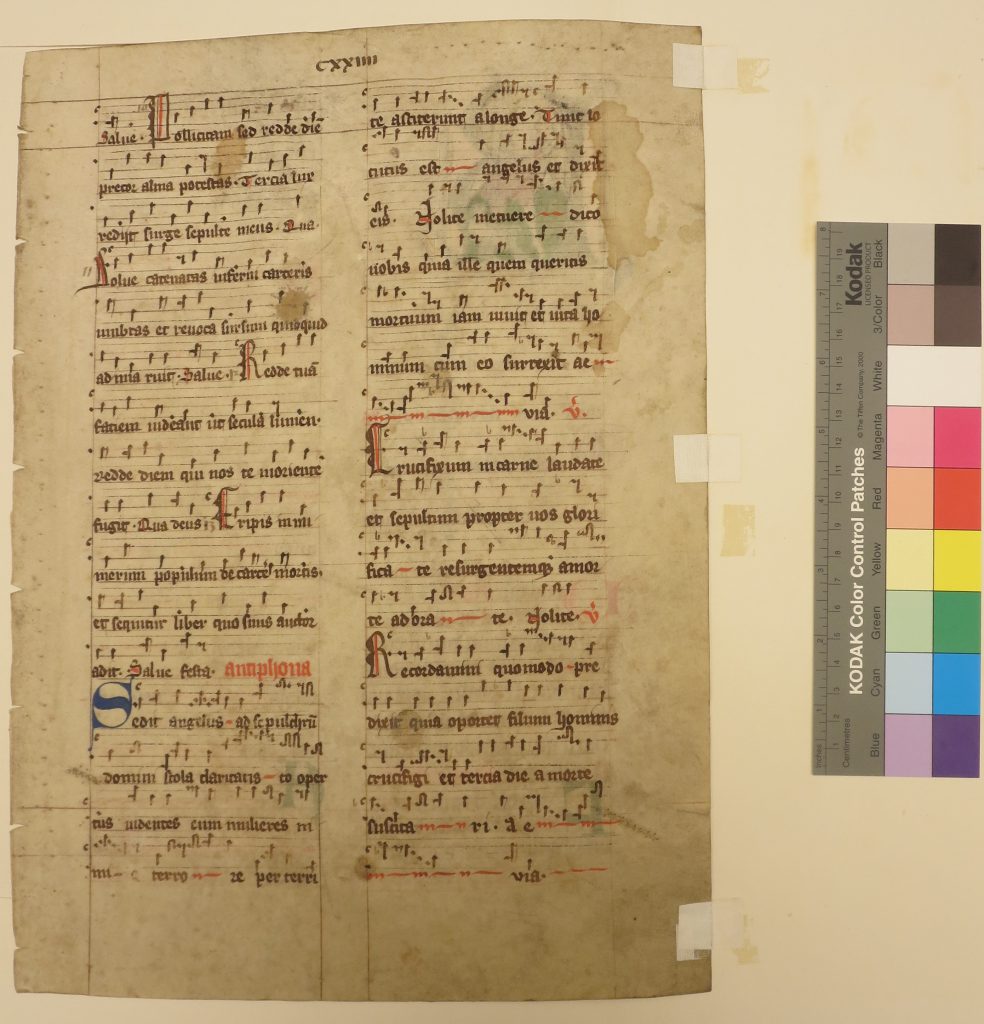

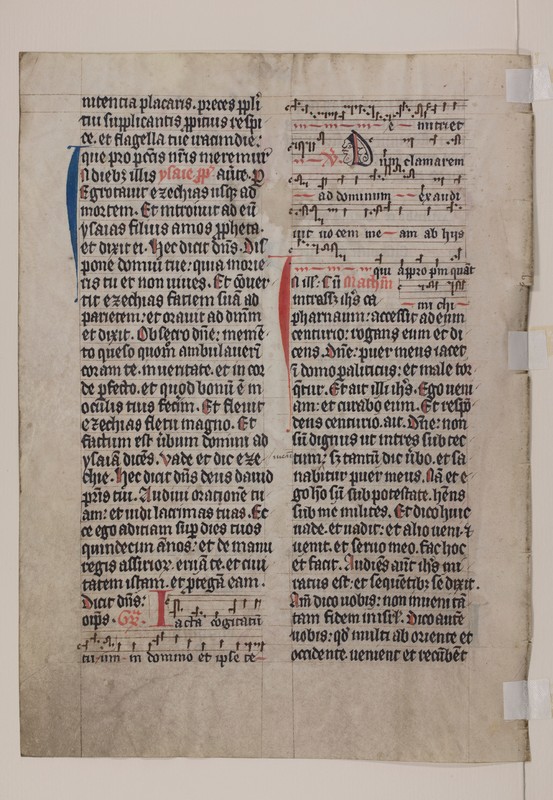

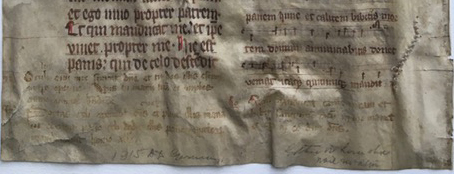

J. S. Wagner Collection, Ege Manuscript 22, Folio clvi, recto, within its frame.

The Wagner Leaf

from Ege Manuscript 22

***

“The Warburg Missal”

Folio CLVI in the Temporale

with Part of the Mass for Corpus Christi

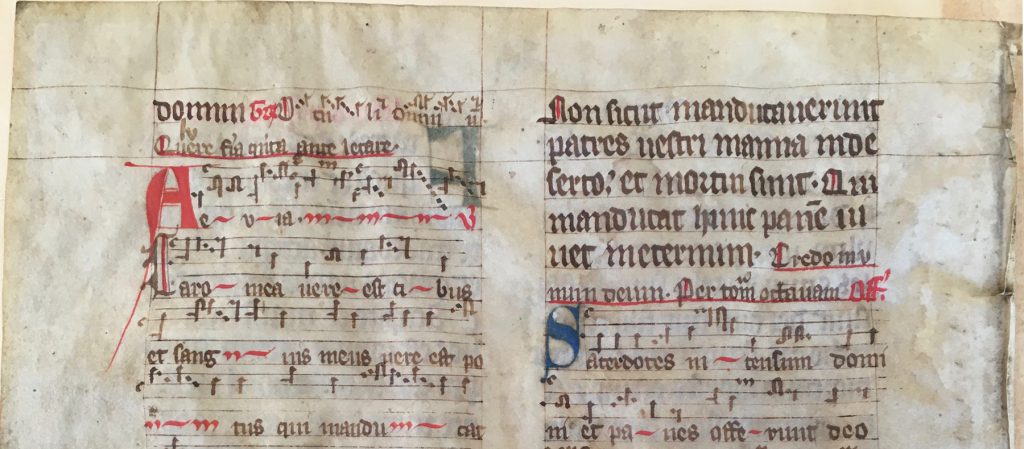

Latin Missal made in Germany circa 1325 Written in Gothic Script (Textualis)

Double columns of 31 lines

Circa 360 × 257 mm < written area circa 289 × 190 mm >

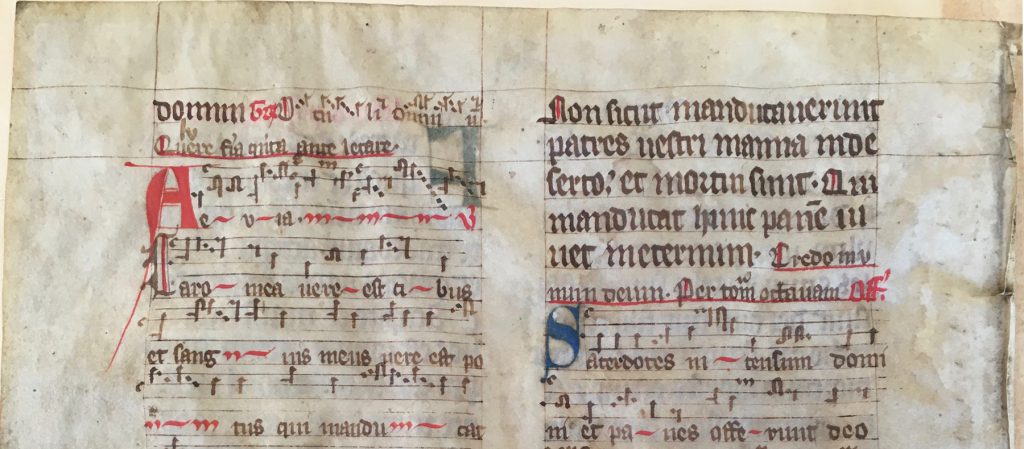

with Rubrications, Inset Initials in Red or Blue, and Musical Notation in Hufnagelschrift (“Horseshoe-Nail Notes”) on 4-Line Staves

With thanks to the collector, J. S. Wagner, we examine a newly identified leaf from one of the manuscripts dispersed by Otto F. Ege (1888–1951). It comes from ‘Ege Manuscript 22’, a Latin Missal written in double columns of 30–32 lines in Gothic Script, with musical notation.This blogpost by Mildred Budny and the companion Report Booklet (2021) by Leslie J. French examine the Leaf, set it in context of its former manuscripts, and re-assess the attribution of the book.

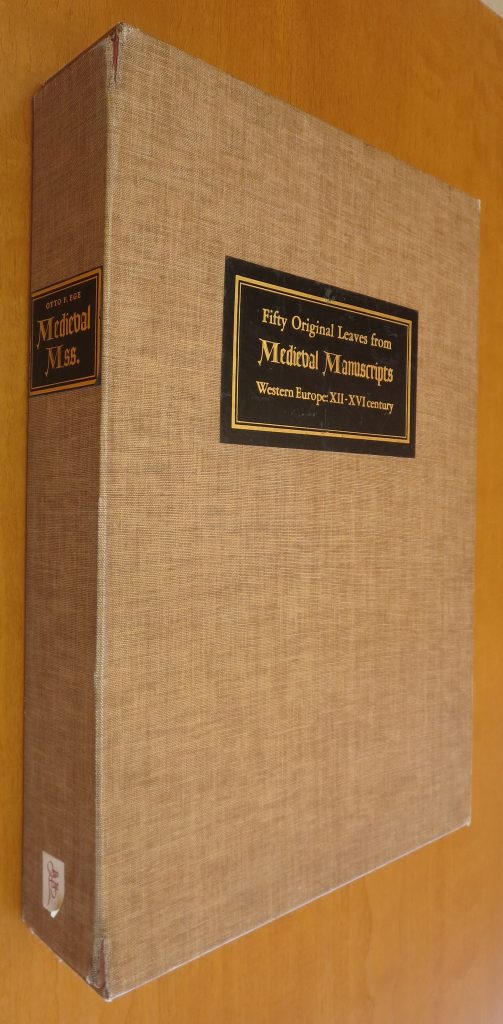

The ‘Ege’ Number comes from the position of this manuscript (and its portions) in Ege’s distribution within one of his Portfolios of specimen leaves forcibly extracted from manuscripts and printed books. The Portfolio in question exhibits Fifty Original Leaves (FOL) from Medieval Manuscripts, Western Europe, XII–XVI Century. In this case, Leaf Number 22. The numbering system is defined and enshrined in Scott Gwara’s “Handlist” of Otto Ege’s Manuscripts (2016).

In the FOL Portfolio, specimens from the manuscript travelled, in their individual windowed mats, in the company of other Ege manuscript leaves. The Wagner Leaf, however, travelled on its own, through a different highway of circulation. It arrived in a glass-fronted ornamental frame. Behind that frame, Ege’s handwritten note on the recto, and the accompanying printed slip (see below), directly establish the Ege connection. All the features of text, script, musical notation, and folio numeration manifest a place within Ege’s Manuscript 22, as the collector readily discerned.

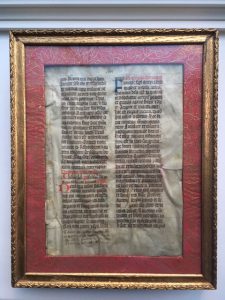

J. S. Wagner Collection, Leaf from Ege Manuscript 22, verso, bottom right: Ege’s inscription in pencil.

Ege Manuscript Leaves and the Wagner Collection

Some of our earlier blogposts have considered other manuscripts collected and dispersed by Otto F. Ege in his several Portfolios and in other ways. See our Contents List. This is the first time that we consider Ege Manuscript 22 in detail.

We introduce a single leaf which has entered the J. S. Wagner Collection.

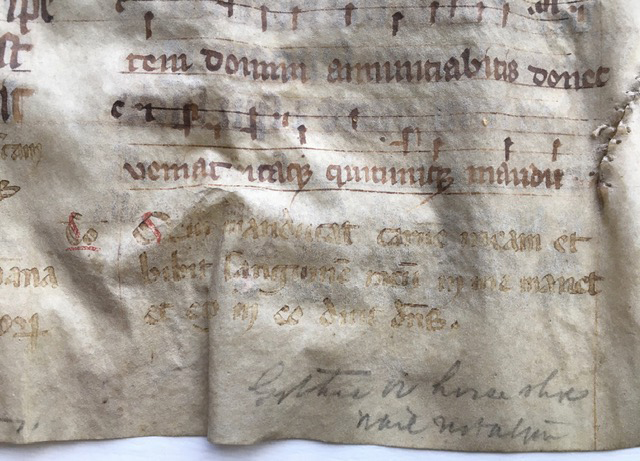

Some materials in the same Collection, in manuscript and early printed form, have already appeared among our blogposts. They include a leaf from another Ege Manuscript, “Ege Manuscript 19”, a 13th-century Vulgate Bible from Italy. Its features include lively animated initials, as here, in the polychrome initial U (for Ut).

Opening of the Book of Maccabees in Otto Ege MS 19. Private Collection.

The Wagner Collection and Ege Manuscript Leaves

1) Posts in our blog about other materials in the Wagner Collection have considered:

J. S. Wagner Collection. Leaf from from Prime in a Latin manuscript Breviary. Leaf “4” Recto, detail.

- Carmelite Missal Leaf of 1509

- The Penitent King David from a Book of Hours

- A Leaf from Prime in a Large-Format Breviary .

- A Leaf from ‘Otto Ege Manuscript 19’ and Ege’s Workshop Practices

- Updates for ‘Otto Ege Manuscript 19’

- Updates for Some ‘Otto Ege Manuscripts’ (Ege MSS 8, 14, 41, and 61)

- Some Leaves in Set 1 of ‘Ege’s FOL Portfolio’ (Ege MSS 8, 14, 19, and 41)

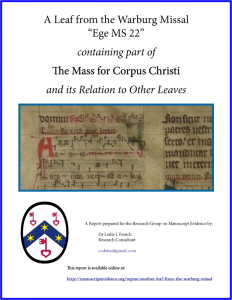

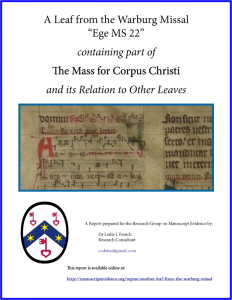

Now we describe the “New Leaf” from Ege Manuscript 22, and introduce the Booklet by Leslie J. French on

A Leaf from “Ege Manuscript 22” containing part of The Mass for Corpus Christi and its relation to Other Leaves.

Laid out in accordance with our Style Manifesto and set in our copyright multi-lingual font Bembino, the booklet is freely downloadable here.The “Find-Place”

Sending us a set of images for the new Wagner Leaf from Ege MS 22 in December 2020, J. S. Wagner reported:I acquired it from a recent Paul Arsenault auction. He is located in South Paris, Maine. A person there told me that the leaf was consigned by a Mrs. McDermott of Manchester, NH. There were no other manuscripts in the material she brought for auction.

J. S. Wagner Collection, Ege Manuscript 22, Folio clvi, recto, within its frame.

The brief description on the label on the back of the frame was a dead giveaway and it was the work of 5 mins to match up the description with Ege 22. There are quite a few other leaves from that manuscript already online so comparisons were easy.

An attachment which J. S Wagner sent with the photographs conveniently assembled a group of materials from online resources. They include Ege’s Label for his Leaf 22, images from other Leaves now in several institutional collections, and a link to the Sotheby’s e-catalogue for part of the manuscript: illuminated manuscripts ||| sotheby’s l11240lot63xrsen [or 2011 lot 87]. The process of discovery drew upon detective skills:When I bought the Ege 22 manuscript there was no information included – no mention of Ege, Sothebys, or anything similar. What attracted my interest was the label on the back, which looked very familiar, and the faint writing at the bottom.

When it arrived I quickly took it out of the frame and was a bit disappointed to find that there was no mat or any other indications of provenance. The framing was done many years ago, perhaps in the 1950’s.

The folio number confuses me, but I may be reading it incorrectly. All the other leaves I have seen have smaller numbers.

With the images and these materials, gathered by an adept and dedicated collector, we set to work. Here, with thanks to J. S. Wagner, we unveil some results, for comment, suggestions, and further exploration.Otto Ege Manuscript 22: Folio CLVI in the Temporale

Purchased at auction, the Wagner Leaf from Ege Manuscript 22 arrived within a gilt frame and windowed mat. The front of the red mat is decorated in gold with an overall foliate, asymmetrical, geometric pattern. Shown somewhat cropped within the window, the leaf presents its double columns of text and some elements around them.

J. S. Wagner Collection, Ege Manuscript 22, Folio clvi, recto, within its frame.

J. S. Wagner Collection, Ege Manuscript 22, Folio clvi, recto, within its frame: Top right.

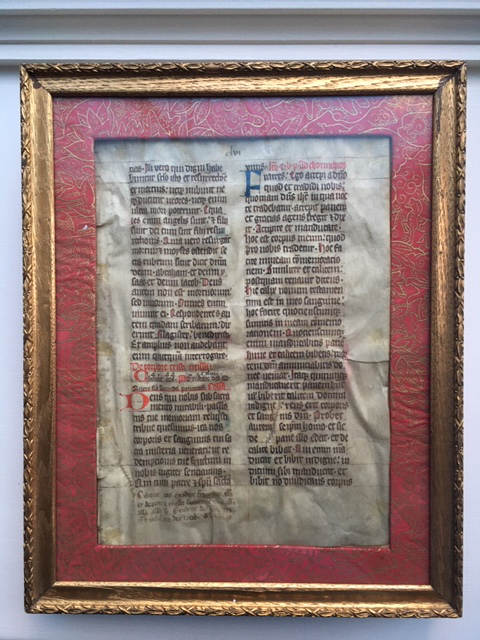

J. S. Wagner Collection, Leaf from Ege Manuscript 22, recto. Reproduced by permission.

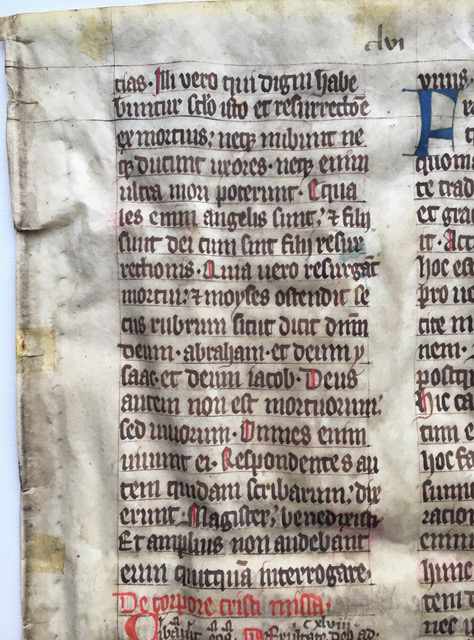

J. S. Wagner Collection, Ege Manuscript 22, Folio clvi, recto, upper right.

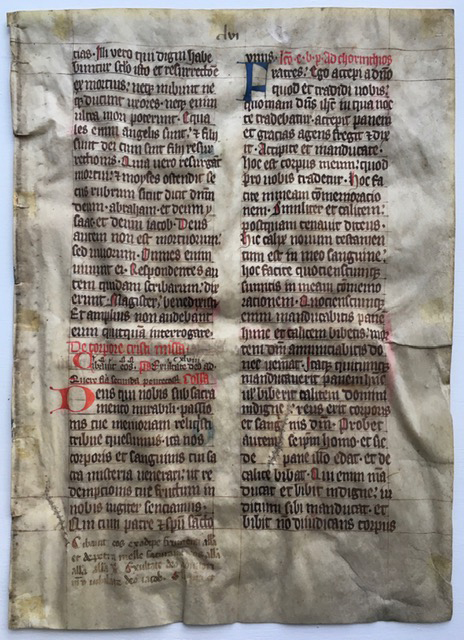

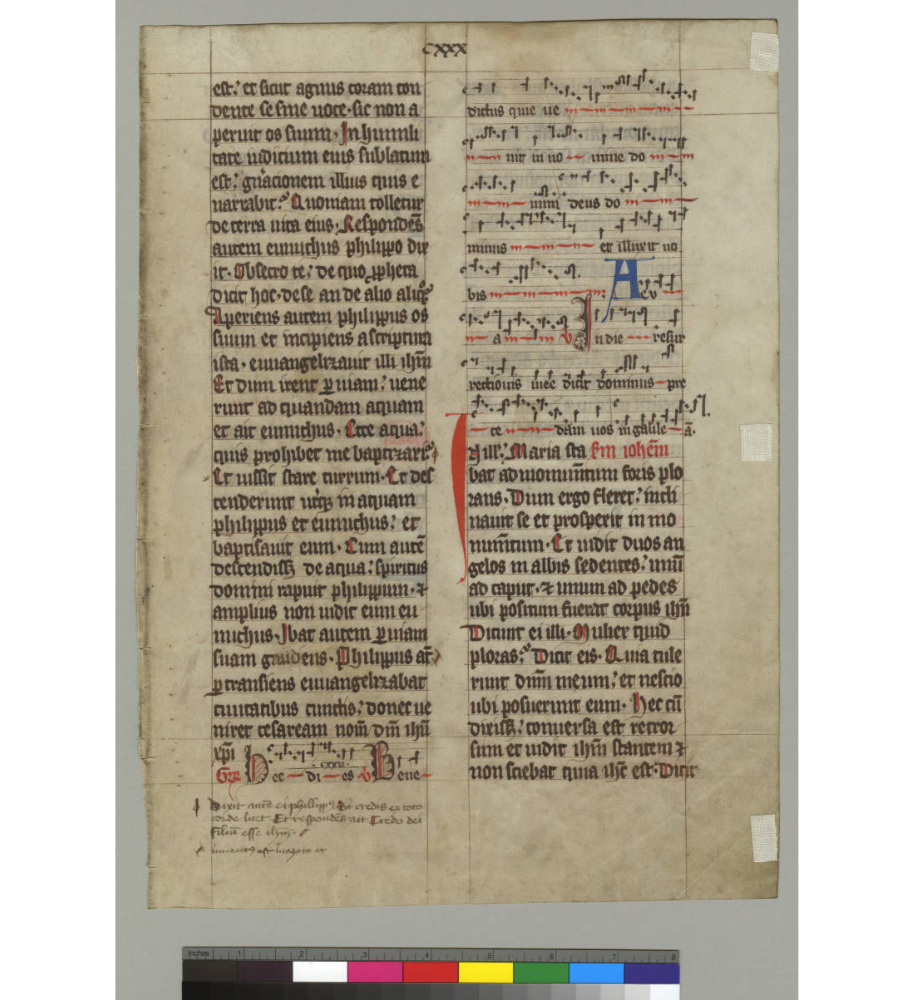

J. S. Wagner Collection, Leaf from Ege Manuscript 22, verso. Reproduced by permission.

J. S. Wagner Collection, Leaf from Ege MS 22, recto, bottom left. Reproduced by permission.

J. S. Wagner Collection, Leaf from Ege MS 22, recto, bottom right. Reproduced by permission.

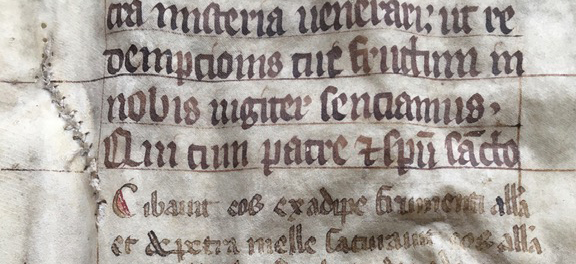

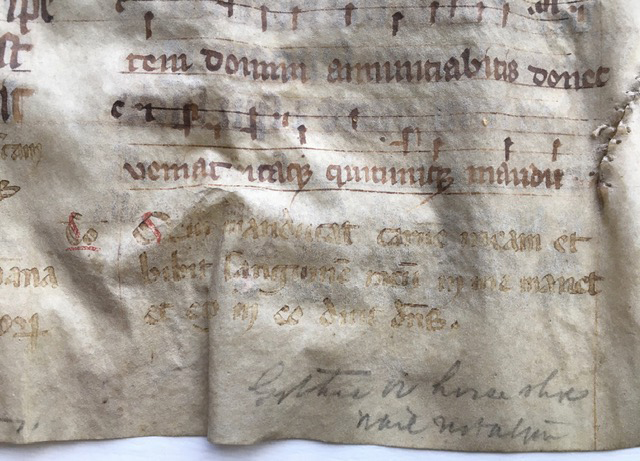

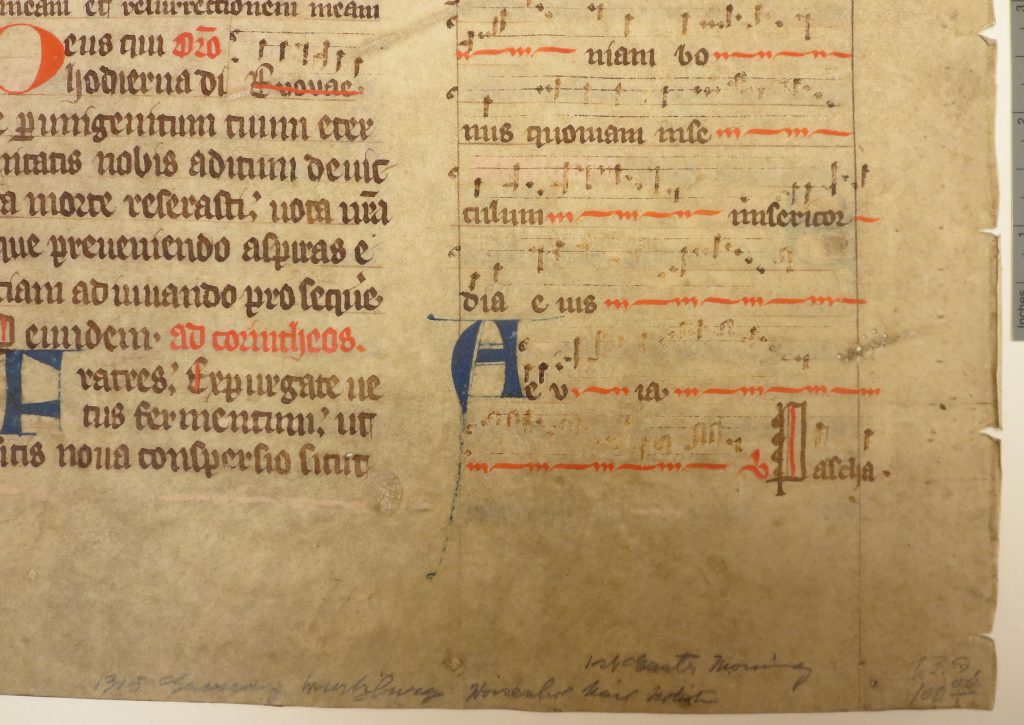

J. S. Wagner Collection, Leaf from Ege Manuscript 22, verso, bottom right: Ege’s inscription in pencil.

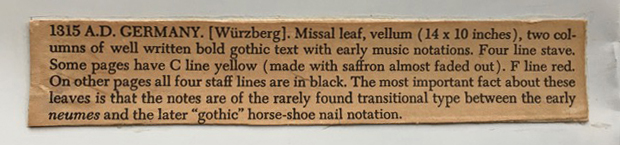

1315 AD Germany. Gothic w[ith] horse shoe nail notation

The Contents

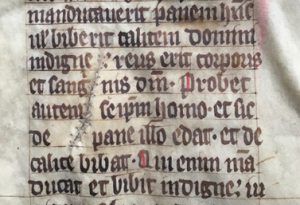

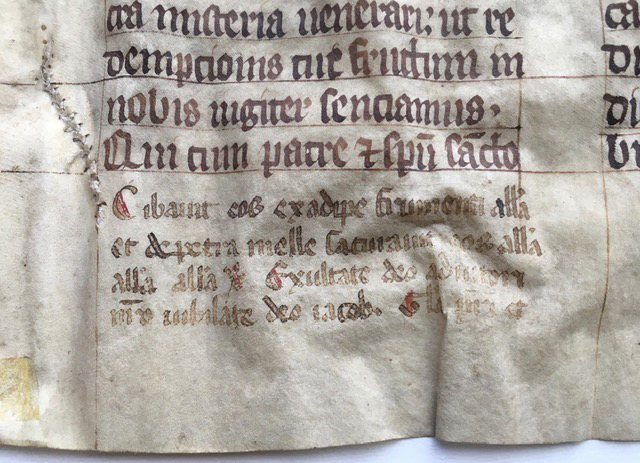

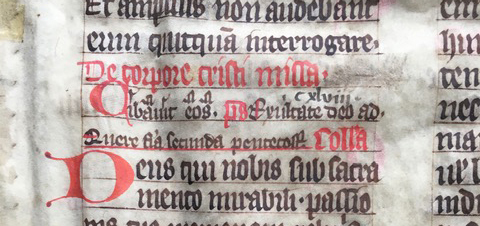

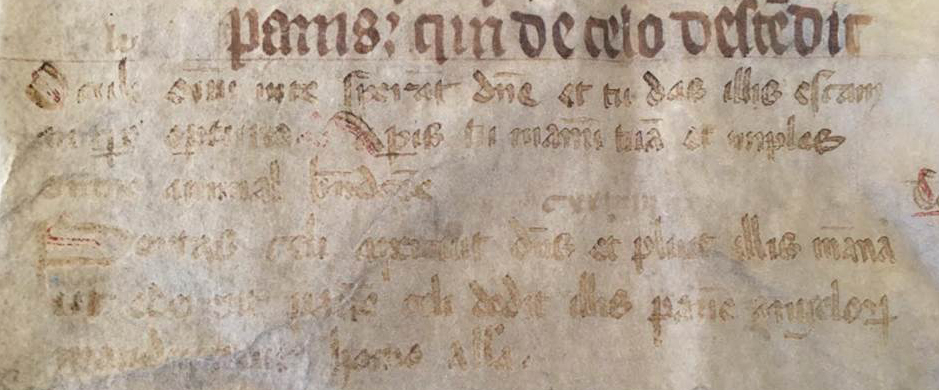

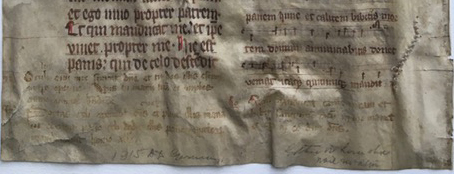

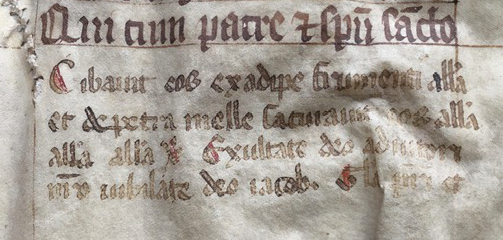

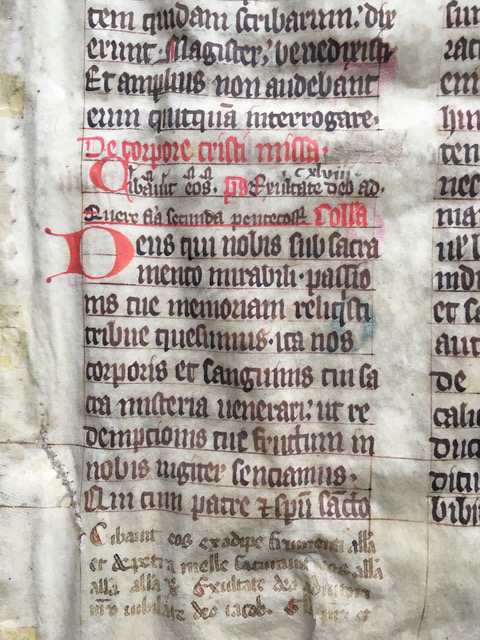

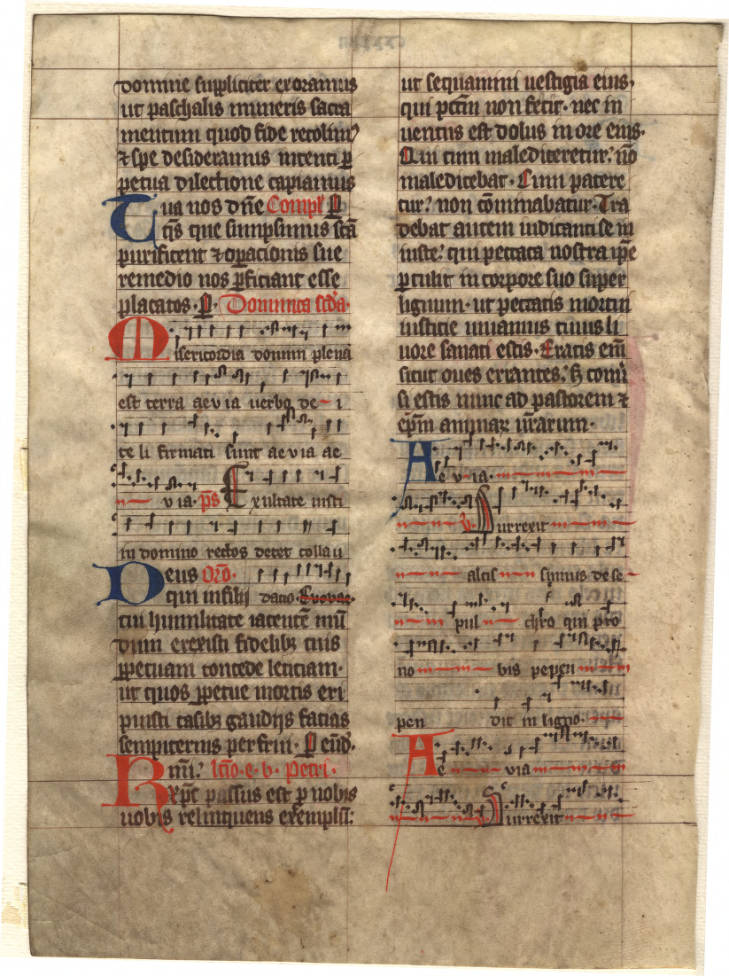

The leaf presents part of the liturgical Mass for the Feast of Corpus Christi in the Temporale. The event is celebrated on the Thursday after Trinity Sunday. All the text on the leaf is transcribed and analyzed in our Report Booklet. The text begins mid-word with “([nup-]tias. Illo” at the top of the recto, within the reading for Luke 20:27–40 in the Vulgate Version. With music at several points, the text ends at the bottom of the verso, again mid-word, with “quincunque mandu[-caverit]” within the reading for 1 Corinthians 11:26–27. Added text in the lower margins on both recto and verso supply further readings to be included in the liturgical performance at these points.

J. S. Wagner Collection, Ege Manuscript 22, Folio clvi, recto, bottom left.

- folio cxlviii (added in the interline above col.a line 21 on the recto)

J. S. Wagner Collection, Ege Manuscript 22, Folio clvi, recto: Column a, detail. Reproduced by permission.

- and folio lv (added in the interline above col.a line 2 on the verso).

J. S. Wagner Collection, Ege Manuscript 22, Folio clvi, verso: Top. Reproduced by permission.

J. S. Wagner Collection, Ege Manuscript 22, Folio clvi, verso: Bottom Left. Reproduced by permission.

J. S. Wagner Collection, Leaf from Ege MS 22, recto, bottom. Reproduced by permission.

J. S. Wagner Collection, Ege Manuscript 22, Folio clvi, recto, bottom left.

J. S. Wagner Collection, Ege Manuscript 22, Folio clvi, recto, lower left.

The Accompanying Slip as Label

A printed slip accompanied the leaf in its frame.

J. S. Wagner Collection, Printed Slip accompanying Leaf CLVI from Ege Manuscript 22. Reproduced by permission.

Clippings from Ege Mat and Label for an Item 26, accompanying a Leaf from Ege Manuscript 61. Courtesy of Flora Lamson Hewlett Library, Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, CA. Reproduced by permission.

1315 A. D. Germany (Würzberg [sic, presumably for Würzburg]). Missal leaf, vellum (14 × 10 inches), two columns of well written bold gothic text with early music notations. Four line stave. Some pages have C line yellow (made with saffron almost faded out). F line red. On other pages all four staff lines are in black. The most important fact about these leaves [my emphasis added] is that the notes are of the rarely found transitional type between the early neumes [on which see Neume] and the later “gothic” horse-shoe nail notation.

As usual (see our our blogposts), Ege’s claims for his manuscripts call for inspection, and sometimes for revision. Revision is called for here. This is a case where Ege reproduced his source of information, misread it, or both. The question is: Würzberg, Würzburg, or somewhere else? Read on, Dear Reader.Würzburg

The city of Würzburg is situated on the River Main in the traditional region of Franconia in the north of the German State of Bavaria.

Marienberg Fortress and Old Bridge at Würzburg. Photograph By Christian Horvat. Own work, Public Domain, via https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=167812.

- A map of Herbipolis shows the layout of the location.

- A detailed list of its various religious foundations indicates their locations.

- A study surveys these foundations over time: 20155-49081-1-PB.pdf.

Wax Seal Impression of the Seal of Wurzburg. Photograph by Wolfgang Sauber. Own work, Public Domain, via https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3268470

- Folio XXVI in Set 6 of FOL at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst (Missale Herbipolensis)

- Folio XXXVIII in Set 13 of FOL at Stony Brook University Libraries (Missale Herbipolense)

- Folio CXXXVIIII in Set 38 of FOL at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro (Missale Herbipolense)

A Warburg Missal

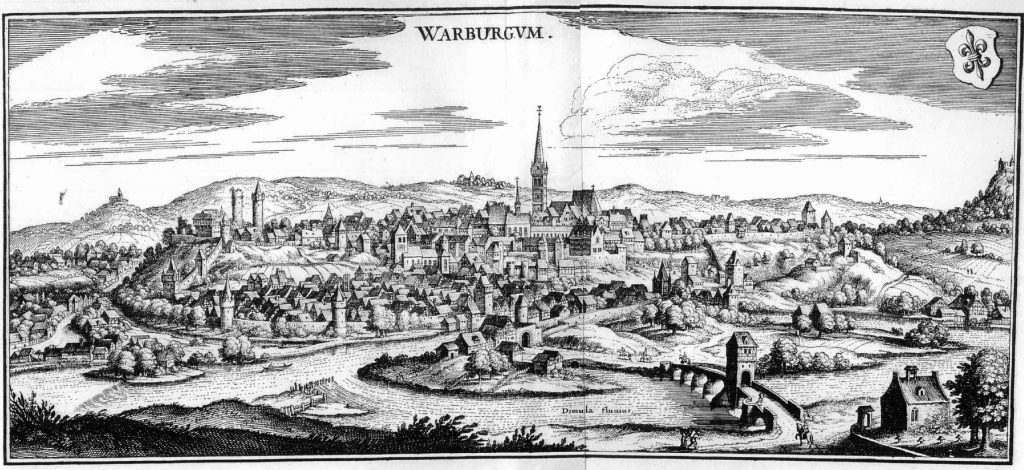

An inscription preserved in the book, as recorded by several bibliographical reports, indicates that the volume was owned by the end of the 17th century by a Parish Church dedicated to Saint John the Baptist, with connections to Warburg in Westphalia, and presumably or perhaps located there. The wording of the inscription deserves examination. So far, we have not seen the inscription itself, or an image of it, so we examine its citations. Warburg the place is “a town in eastern North Rhine-Westphalia on the river Diemel near the three-state point shared by Hessen, Lower Saxony and North Rhine-Westphalia”. Close to Paderborn, to which diocese it belongs, Warburg lies about 100 miles to the north-east of Cologne or Köln. The distance between Warburg in Westphalia and Würzburg in Bavaria is about 122 miles. An engraving published in 1647 shows a view of the city about half a century before the date of the inscription. At about its center looms a multi-tiered tower with a long, tapered, spire.

The City of Warburg, in an engraving by Matthäus Merian for the Topographia Westphaliae (= Topographia Germaniae, Volume 8) published 1647. Image Public Domain.

Warburg, Neustadt-Kirche / St. Johannes Baptist in Warburg. Photograph on 26 May 2017 by Kno-Biesdorf – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, via https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=63450859.

Ege Manuscript 22

Known through various reports and dispersed portions, ‘Otto Ege Manuscript 22’, representing the fragments of a Latin manuscript Missal produced in Germany sometime in the first portion of the 14th century, is reported or described in multiple ways. Those varieties depend upon the different positions which the manuscript occupied relatively1) in the hand-off of its possession from one owner to another, thence to Ege and, in pieces, elsewhere; and

2) in its dispersal as separated components of 1 or more leaves, variously within Ege’s FOL Portfolio or in other forms.

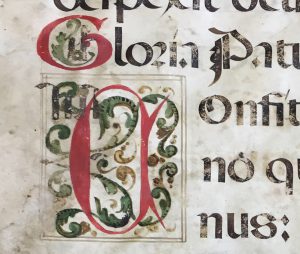

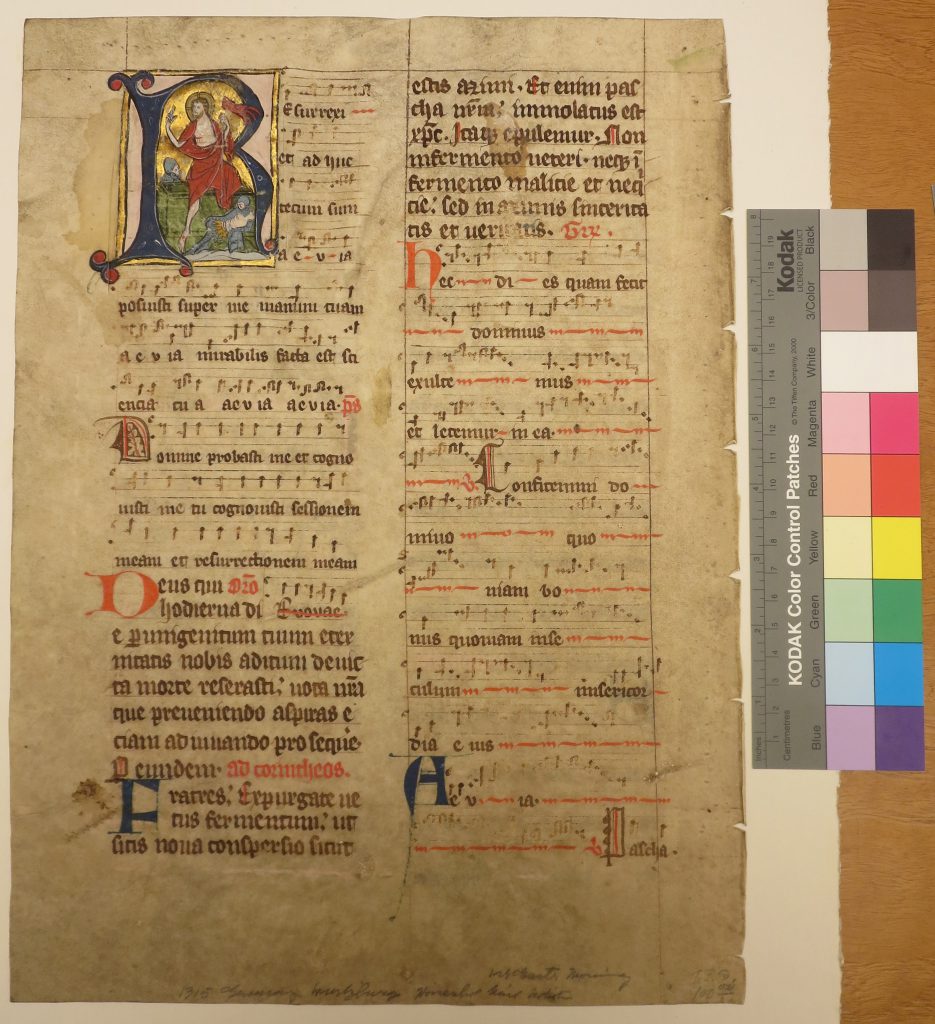

A sample of the manuscript, on a Leaf in the Otto Ege Collection at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, appeared in the Booklet for our 2016 Symposium on Words & Deeds, available here (Figure 13). Its illuminated initial R for Resurrexi (“I have arisen”) opens the chant in the (or a) reading for Easter or Resurrection Sunday.![Illustrated initial R for 'Resurrex[i]' on a leaf from 'Otto Ege MS 22' ('The Beauvais Missal'). Otto Ege Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. Photograph courtesy Lisa Fagin Davis. Reproduced by permission.](https://manuscriptevidence.org/wpme/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/FOL-22a-detail-rotated-cropped-839x1024.jpg)

Illustrated initial R for ‘Resurrex[i]’ on a leaf from ‘Otto Ege MS 22’ (‘The Beauvais Missal’). Otto Ege Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. Photograph courtesy Lisa Fagin Davis. Reproduced by permission.

Ege’s Mat and Label

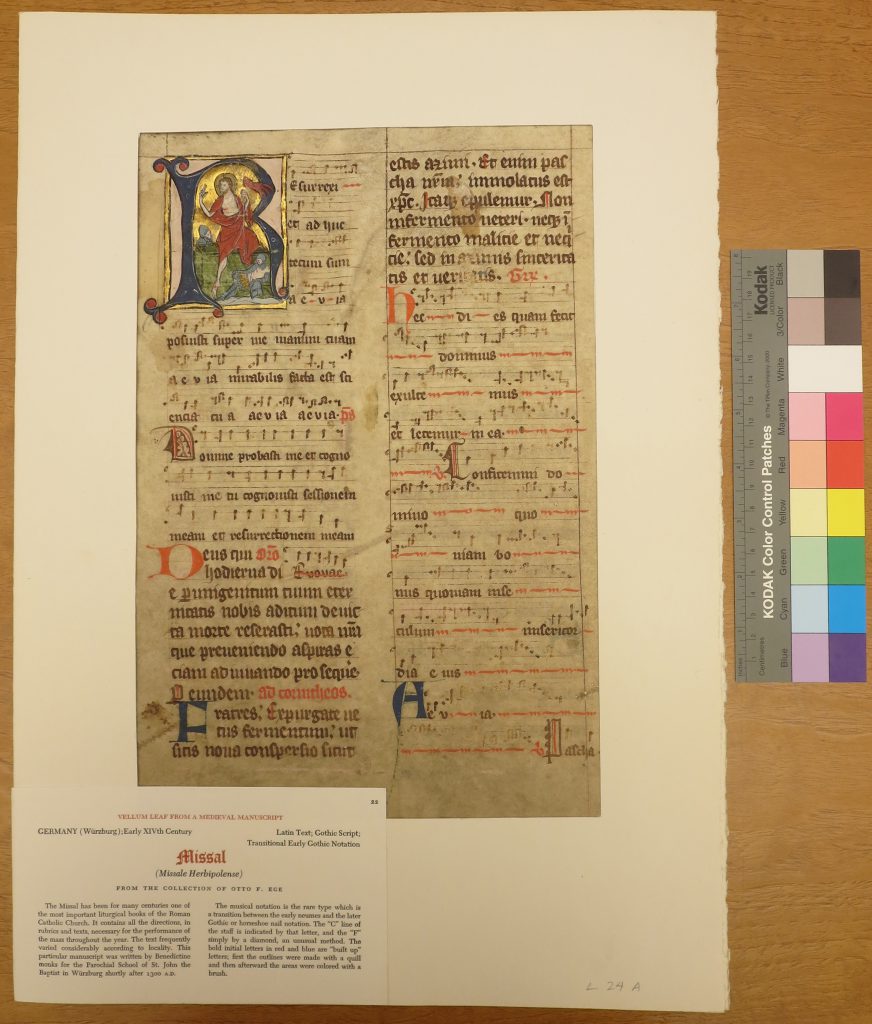

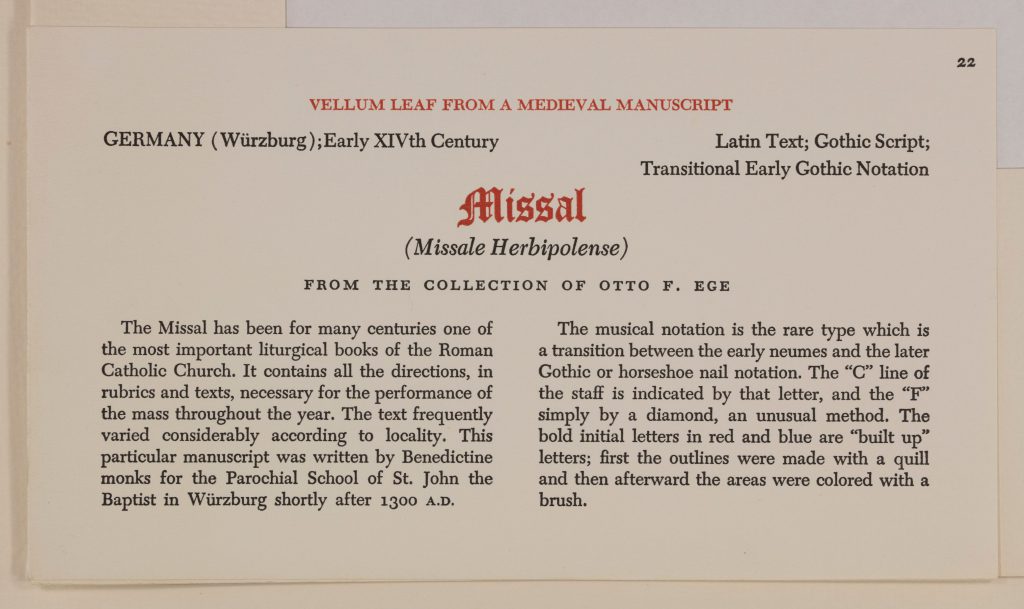

In its mat, Ege presented the leaf thus for the Portfolio:

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, Leaf 22 in mat. Photography Mildred Budny.

Otto F. Ege: Fifty Original Leaves from Medieval Manuscripts, Leaf 22, Printed Label, Special Collections and University Archives, Stony Brook University Libraries.

The Missal . . . contains all the directions, in rubrics and texts, necessary for the performance of the mass throughout the year. . . . This particular manuscript was written by Benedictine monks for the Parochial School of St. John the Baptist in Würzburg shortly after 1300 A.D. . . .

The Label takes a leap of faith, from the reported ownership by the ecclesiastical establishment “in Würzburg”, to an assertion that the manuscript was made for it “shortly after 1300 A.D.” The second paragraph focuses upon the “rare type” of transitional musical notation and the method of constructing the “built-up” initial letters. “First the outlines were made with a quill and then afterward the areas were colored with a brush.” The manuscript page in full, below the framed mat, shows its full contours in the forms that its history has retained.

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, Leaf 22. original verso revealed under mat. Photography Mildred Budny.

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, Leaf 22. original recto, with Ege’s mounting tapes. Photography Mildred Budny.

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Otto Ege Collection, FOL Set 3, Leaf 22. original verso, bottom right. Photography Mildred Budny.

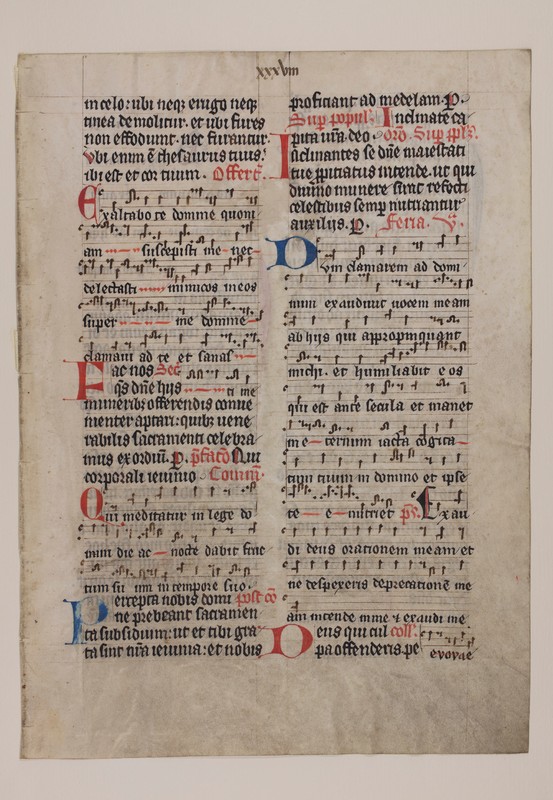

Other Parts of the Book: FOL and More

Firstly, the position as specimen Leaf 22 within Ege’s Portfolio of Fifty Original Leaves from Medieval Manuscripts, Western Europe: XII–XVI Century (FOL) offers a point of departure for searching for cognate leaves. The Portfolio has 40 numbered sets and at least 1 unnumbered set. The present locations of some sets are accounted for. Some of their contents are displayed online, with digital facsimiles of one or both sides of the given leaf (in varying quality). Note that not all the sets retain their full set of Specimen leaves. Some locations for FOL are listed in- Scott Gwara, Otto Ege’s Manuscripts, (2013), Appendix VIII (pages 106–107) See the Handlist, Number 22 (page 125).

- Denison University, Otto F. Ege Collection: The Ege Manuscript Leaf Portfolios. See Leaf 22.

- Umilta, THE OTTO F. EGE PALEOGRAPHY PORTFOLIO See [Unidentified Specimen for Ege 22] = Probably folio CXXIX verso, as the page has the rubric fia.v. (in the middle of column a), for feria V infra octavam pasche.

Some Specimens

Front Cover for Report by Leslie J. French for Wagner Leaf from Ege MS 22 (2021)

A Note on the Folio Numerations

This Missal has “medieval foliation in several sequences”, as noted for the portion of 125 leaves sold as lot 52 (along with the binding) on 11 December 1984.The Calendar was unfoliated. The Temporal was foliated in black ink in roman numerals in the centre of the upper margins. The Canon was unfoliated. The Sanctoral was foliated from 1 again in roman numerals in the centre of the upper margin and in arabic numbers in red on the right-hand side of rectos; this ceases from 78 in that sequence (f.92 in the manuscript as it survives).

Such variations are visible as well on leaves outside the span of that catalogue. See below and Leslie French’s Report Booklet (2021).Sampling of Numbered Leaves

The original, medieval, numbering on the leaves in the Bergendal Portion of Ege MS 22 is not fully visible at present. Partial reports or views of that numbering can be examined in entries for the 1984 and 1985 Sotheby’s catalogues for its 2 sections respectively, the 1999 Bergendal Collection catalogue of their reassembly, and the 2011 Sotheby’s online catalogue. The selected images for the latter include the openings with two rectos: Folio cvi (pencil 49) and Folio cxvi (pencil 58). The Bergendal catalogue (pages 1–4) unfortunately cites the leaves only by their subsequently imposed arabic numbers in pencil within that reassembled Portion of the book (numbers 1–145). Those leaves are said to be “foliated in pencil in a late twentieth century American hand” (page 1). The images for the 2011 Sotheby’s e-catalogue show examples. A sampling of leaves outside the Bergendal Portion is listed below by their original folio number in numerical order, distinguishing between their positions within numberings for the Temporal or Sanctoral. They might provide an initial framework for virtually grouping other survivals within their former context in the book. Folio III in the Sanctoral. Scott Gwara Private Collection. Scott Gwara, Otto Ege’s Manuscripts (2016), Frontispiece (recto in color). Folio XIIII. Toledo, Ohio, Toledo Museum of Art (Set 12 of FOL). Folio XIIII in the Temporal and Leaf CXXI in the Temporal. Boston, Massachusetts, Endowment for Biblical Research, Endowment Collection, MS. Leaves 77–78. Judith Oliver, ed., Manuscripts Sacred and Secular from the collections of the Endowment for Biblical Research and Boston University (Boston, 1985), no. 68 (page 42). Folio XXXIX in the Sanctoral. Saskatchewan, University of Saskatchewan, Murray Library (Set 25 of FOL). David Bindle, et al., 50 Medieval Manuscript Leaves: The Otto Ege Collection, University of Saskatchewan Library (Saskatoon, 2011), no. 22 (pp. 102–105). Folio XXXVIII in the Temporal. Stony Brook, New York, Stony Brook University, Special Collections and University Archives (Set 13 of FOL), Leaf XXXVIIIRecto

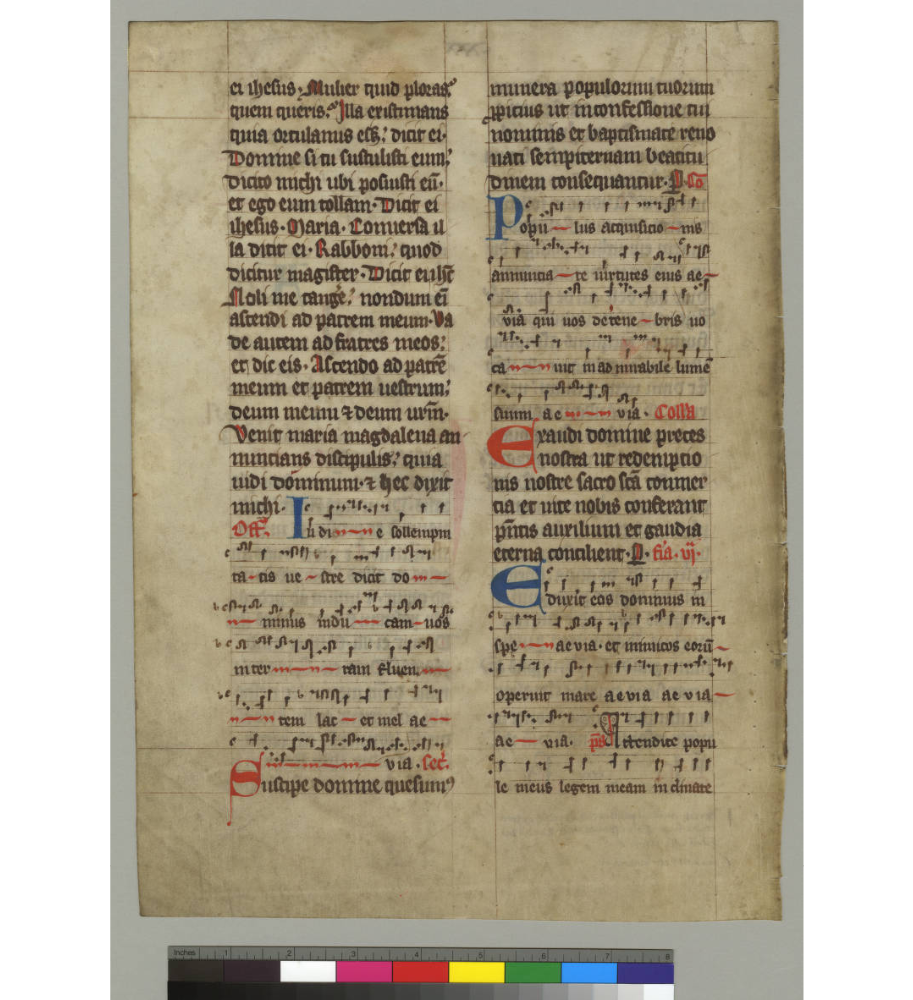

Otto F. Ege: Fifty Original Leaves from Medieval Manuscripts, Leaf 22, Recto, Special Collections and University Archives, Stony Brook University Libraries.

Verso

Otto F. Ege: Fifty Original Leaves from Medieval Manuscripts, Leaf 22, Verso, Special Collections and University Archives, Stony Brook University Libraries.

Recto

University of Minnesota Libraries, Ege Manuscript 22, ‘Verso’ (Original Recto). Image Public Domain.

Verso

University of Minnesota Libraries, Ege Manuscript 22, ‘Recto’ (Original Verso). Image Public Domain.

Verso

Columbia, University of South Carolina, University Libraries, Ege FOL Set 27, Leaf 22. verso. Public Domain.

Ownership and Provenance

Of the origin of the manuscript, apparently we must depend upon its style of script, layout, musical notation, annotations, and other features. Some evidence, both internal and external, preserves indications of its ownership across parts of its history.1) Parish Church of Saint John the Baptist, Warburg in Westphalia

Warburg, Neustadtkirche. Photograph by Kno-Biesdorf – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, via https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=63450859.

Flyleaf ownership inscription of the parish church of St. John the Baptist, Warburg, dated 6 June 1682.

—— William P. Stoneman, “A Summary Guide to Manuscripts in the Bergendal Collection, Toronto”, in A Distinct Voice: Medieval Studies in Honor of Leonard E. Boyle, O. P. , edited by Jacqueline Brown and William P. Stoneman (Notre Dame, Indiana, 1997), pp. 163–206, at p. 193.

Other reports quote its text. They do so either implicitly and in part (1947 Sotheby’s catalogue), or explicitly and possibly in full (as in the 1984 Sotheby’s catalogue and the 1999 Bergendal catalogue), perhaps expanding silently any abbreviations of the original.Hic liber ad usum Ecclesiae parochalis Sancti Johannis Batistae renovatus est Warburgi anno [1]682, 9 Junii.

—— Christopher de Hamel, Sotheby’s, Western Manuscripts and Miniatures, 11 December 1984, lot 52.

—— Joseph Pope, One Hundred and Twenty-Five Manuscripts: Bergendal Collection Catalogue (Toronto: Brabant Holdings, 1999), Bergendal MS 69, pp. 1–4 (at page 4).

—— Sotheby’s, 5 July 2011, lot 87.

That is, perhaps,“This book, for the Use of the Parochial Church of Saint John the Baptist, was renovated [or restored, perhaps rebound] at Warburg in the year 1682, on the 9th of June”.

The word order appears to indicate that Warburg pertained more to the location of the renovation (whatever that was) than to the Church. However, who can tell, at this distance, how precise or imprecise was the choice and order of wording? The wording does not exactly state that the church owned it, as do many forms of ex-libris inscriptions or marks. Instead, it remarks that the church has (or was to have) the liturgical Use of the book, while it records a “renovation” of some sort at Warburg in (or by) a specific date in 1682. An assumption that the “renovation” took place in the same town as the location of the Parochial Church may or may not be justified. At least, a Parochial Church with that dedication is known at Warburg, so that the assumption could be plausible, unless shown otherwise.The Book Before 1682

The date of the inscription leaves a long gap between the manufacture of the manuscript for ecclesiastical use (and Use), apparently somewhere in German realms in the High Middle Ages, and the recorded presence of the volume among the projected appurtenances of the Parochial Church at (or near) Warburg in the early modern period. Thus we should, indeed we must, keep in mind a distinction between the Provenance (Location in Warburg, at least for renovation, by inscription dated to 1682) and the Origin, or Provenience (Location “TBD”). (See also Provenience). Upheavals affecting religious as well as other institutions in these realms during the intervening period, between the first half of the 14th and the latter part of the 17th century, impacted the dispersal and re-distribution of many ecclesiastical (and other institutional) books before, during, and after the Reformation in the 16th century. A telling example is explored in our blog for a set of medieval Selbold Cartulary Fragments. Such disruptions have, it seems, impacted the transmission of knowledge about Ege Manuscript 22 — to its detriment.From Leander Van Ess to Thomas Phillipps & Beyond

Subsequently the volume entered private hands, in an intricate series of transactions.2) Johan Heinrich (or Leander) van Ess/Eβ (1772–1847)

Portrait of Leander van Eß by Martin Esslinger (1793-1841), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

- Leander van Ess or Johan Heinrich van Ess / Leander van Eß (1772–1847), a German Catholic theologian, born at Warburg in Westphalia.

- Sammlung und Verzeichniss handschriftlicher Bücher . . . welche besitzt Leander van Ess (Darmstadt, 1823), p. 24.

131. Missale. Auf 322 Pergamentblätter mit grosser Missalschrift und Choralnoten schön geschrieben, enthält mehrere auf Goldgrund gemalte Bilder und viele gemalte Initialen, weicht ebenfalls von der jetzt bestehenden Liturgie der Messe ab; ist sehr gut erhalten, in starkem Lederband gebunden. Folio magno.

Concisely, the entry records the type of book (Missale), the number of its leaves, and other features, ranging from script and musical notation to condition, binding, and format.- 322 “parchment leaves”

- the “large” and “beautifully written” liturgical script (“Missal-type Script”) and musical notation for the choir (“Choral-type Notation”),

- the “multiple painted images (Bilder) on gold background” [that is, in historiated initials and/or other settings],

- the “many painted initials”,

- the deviation of the text “from the current liturgy of the Mass” [i. e. from the Tridentine, in use from 1570 onward],

- the “very well preserved” condition,

- the “strong [or stout] leather binding”, and

- the format in folio magno (“large folio”; see Folio).

- Milton McC. Gatch, The Book Collections of Leander Van Ess, with further references.

- Sigrid Krämer, “A Manuscript Catalogue of the Nineteenth Century: Leander van Ess’s Description of the Books Sold in 1824 to Sir Thomas Phillipps”, Gazette of the Grolier Club, New Series, 48 (1997), 91–105.

A close examination of the collection assembled by Van Ess yields salient observations. For example,

Although he was never a wealthy man, historical circumstances made it possible for Leander van Ess to acquire large collections of valuable books. He emerged from the monastery into the world because of the secularizing programs of the Napoleonic regime in Germany at the beginning of the nineteenth century.

And so, he “amassed very large collections, apparently at nominal expense.” Among them are

books from Marienmunster, acquired when he left there . . . books from other former monastic libraries, including many from the Benedictine monastery at Hysburg in the diocese of Halberstadt, of which his cousin Carl had been a member . . .

A large number of books originating from a number of south-west German monasteries came from the duplicates collection of the university library at Freiburg im Breisgau. A significant group of manuscripts originated at the Carthusian monastery of St. Barbara in Cologne . . . [etc.]

— Milton McC. Gatch, The Book Collections of Leander Van Ess.

It might be thought that the acquisition of the Warburg Missal derived from connections through Leander / Johan Heinrich’s own origin in that place years before. Not impossible. However, the very wide spread of his acquisitions over a number of years may indicate that he found it instead by some other route. It is not known when or where he acquired the volume, to become Number 131 among 367 manuscripts in his list for their sale. To come into his hands, given his own origins, might have constituted serendipity rather than specific design. Stranger coincidences have happened in the history of book-collecting. Who can say what the volume might have contained, and might, in fragments, still contain, in the forms of notes, marks, and other features that could, properly deciphered, have spoken of its travels from the Parish Church to and through the hands of Leander / Johan Heidrich Van Ess?3) Sir Thomas Phillipps (1792–1872)

Sir Thomas Phillipps circa 1860. Image Public Domain via Creative Commons.

- Thomas Phillipps (1792–1872), renowned English antiquary and book collector.

- Toby Burrows, “Manuscripts of Sir Thomas Phillipps in North American Institutions”, Manuscript Studies: A Journal of the Schoenberg Institute for Manuscript Studies, 1:2 (Fall, 2017), pp. 207–327.

View of Thirlestaine House, Cheltenham, Home of Sir Thomas Phillipps. View from Bath Road. Photograph by Philip Ratzer on 2 October 2013. Image via Creative Commons.

Phillips MS 516 = Ege MS 22

In the many sales of the astonishing Phillips Collection, requiring decades upon decades of dispersal, this Missal manuscript was sold by Sotheby’s in London, along with other Phillips manuscripts and documents, on 1 December 1947. The entry in that sale catalogue provides information not found readily elsewhere. Its representations and interpretations have subsequently affected discussions of the nature and origin of the manuscript — not always for the good. Let us examine its terms. In quoting its full text, I add emphasis in red, and offer comments here and below.- Sotheby & Co., Bibliotheca Phillippica. Catalogue of a Further Portion of the Renowned Library formed by the late Sir Thomas Phillipps . . . (Monday, the 1st of December, 1947), page 17:

Lot 92. Missal. Ad usum Ecclesiæ parochialis S. Johannis Baptistiæ, Würzburg [sic], German MS. on vellum of the 13th Century, 325 ll. (measuring 14in. by 10in.), double columns, with ten historiated initials in gold and colours, besides the full-page Canon Miniature of the Crucifixion, numerous capitals in red and blue, folio, original pigskin over oak boards, remains of clasps (516) S. German, 13th Century

The full-page painting of the Crucifixion, the service of the Mass and the Penitence of David are as usual somewhat and rubbed through usage, but the MS. is a good specimen of a very early Missal in its original state.

In the Calendar (8 July) is commemorated in red, St. Kilian, who suffered martyrdom at Würzburg.

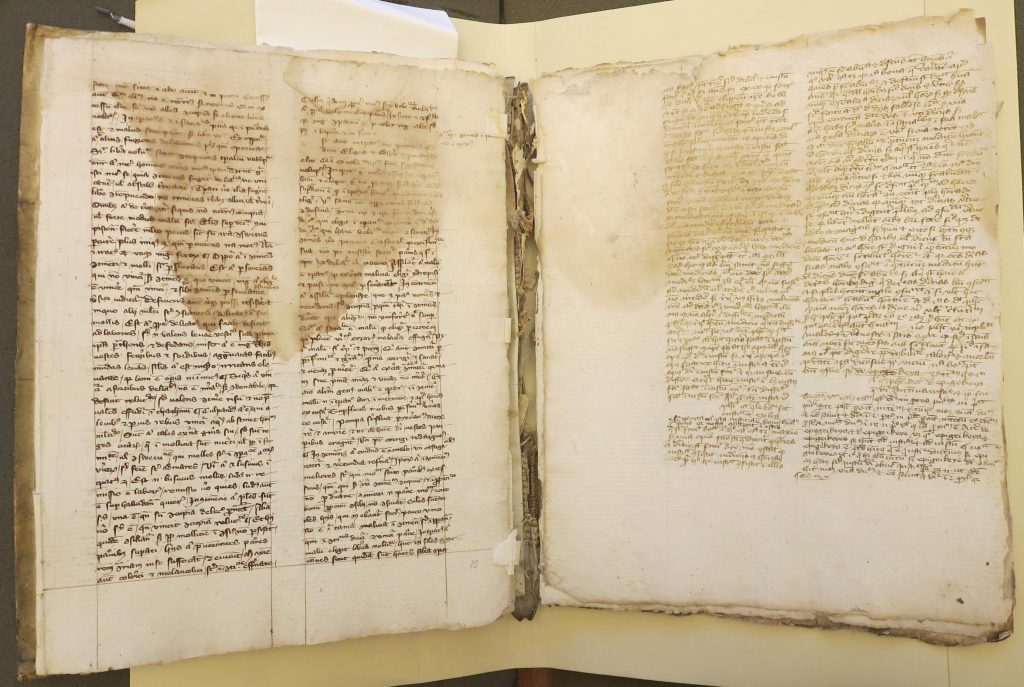

Note the spelling Würzburg, whereas other citations of the inscription report the place as Warburg (Warburgi). Elsewhere, in a later Sotheby’s catalogue (see above and below), an explicit quotation of the “ex-libris” inscription (quoted in full?) shows that the 1947 entry quotes the text of that inscription only partly (Ad usum Ecclesiæ parochialis S. Johannis Baptistiæ, plus that element or mistranscription Würzburg), without further explanation. The 1947 entry specifies the number, location, and material of some elements which the Van Ess catalogue mentions more generally. Mentioned are the different forms of images, distinguishing between initials and a frontispiece (“ten historiated initials in gold and colours”, plus the “full-page Canon Miniature of the Crucifixion”, presumably likewise having gold background). The entry reports elements of the binding, with its “original pigskin over oak boards”, plus the “remains of clasps”. I’m not sure what “(516)” means in the context. Note that the entry declares the “pigskin” binding to be “original“, therefore, presumably, “13th Century“, like the date to which the entry attributes the manuscript and the ensemble. The 2011 Sotheby e-catalogue (5 July 2011, lot 87) illustrates a frontal view of the binding and describes it thus: “early blind-stamped pigskin over wooden boards (with skilful [sic] modern restoration), two clasps”.A Note on the Binding and the Reused Binding Fragments

For a moment, let us consider the binding, insofar as it is reported or illustrated online. Tantalizing is the mention in the e-catalogue of “binding fragments from German fifteenth-century liturgical book now separate”. Re-used binding fragments can be an extraordinarily rich source of information about binding history, provenance, and more. (See, for example, Fragmentology.) Any fragments reused in the binding or rebinding might well provide useful evidence of history and provenance. The auction catalogue yields few specifics. Did the fragments function in situ, as, say, pastedown(s), endleaf/endleaves, spine-liner(s), or some other structures? From what sort of “liturgical book”, presumably deemed obsolete, did they come? Manuscript or early printed? Given the proposed “15th-century” date, printed materials and printing waste would be possible candidates. Was the book in “German”, or rather from (or presumed to be from) Germany (like the manuscript itself), but in another liturgical language (as in, Latin)? Perhaps the reused fragments arrived as part of the “restoration” completed by 6 June 1682. No longer in situ (and thus deprived of some of their evidentiary value), they seem to have been lifted away from the binding in its modern restoration. Like their removal from the volume itself into a “separate” location, the sparse description in the auction catalogue keeps their character and their relationship with the Missal shrouded in disembodied mystery.A Note on Numbers

Perhaps the different number of leaves (322 “vellum leaves” versus 325 “ll.”) — as cited respectively in the Van Ess catalogue and the Phillipps sale catalogue — reflects a different approach to counting the vellum leaves of the manuscript and any endleaves within the book? (Such as the “paper endleaf” which carried the 1692 inscription.) Or did it acquire some extra leaves or inserts along the way? A comparable issue regarding different folio counts by only a few leaves (but with fewer in the later catalogue) arises with Ege Manuscript 40. See Otto Ege’s Aquinas Manuscript in Humanist Script (‘Ege Manuscript 40)”.4) Otto Ege Et Al.

After purchase at Sotheby’s, the manuscript went to:- Otto F. Ege (1888–1951)

J. S. Wagner Collection, Leaf from Ege MS 22, recto, bottom. Reproduced by permission.

Otto Ege’s Portfolio of ‘Fifty Original Leaves’, Set 3. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, 2016. gene. 14. Otto Ege Collection. The Ege Family Portfolio, seen from the Side. Photograph Mildred Budny.

Dispersal, Retrieval, Repeat

As customary, some parts of Ege’s manuscript were sold again, not only as individual leaves, but as groups. In some cases, the residual ‘carcass’, replete with binding, surfaces in the course of resale and redistribution. Examples include Ege MS 14, Ege MS 51, and more. See our Contents List. Now we take the story to stages which followed Ege’s handling of it and its pieces. See Part II of II. *****************5) Bergendal Collection

Collecting substantial remnants of the manuscript focused upon, and benefited from, the Additive Approach. This manuscript joins the company of manuscripts despoiled for Ege’s specimen leaves, left over as a ‘Residue’, and ‘rescued’ in a bulk purchase — sometimes still with the binding. Others include the large portion in the Schøyen Collection of Ege Manuscript 14 (a large-format Lectern Bible) and the multiple remnants in the Otto Ege Collection at Yale of Ege Manuscript 51 (Aristotle et al. in more than 1 volume). A view of the interior in Volume II of the latter shows gaps and rearrangements imposed in extractions.

Beinecke Manuscript & Rare Book Library, Otto Ege Collection, Volume II of Ege Manuscript 51, Folios 15r and 108v (turned as a recto). Photography Mildred Budny.

Part 1: 125 Leaves plus the Binding

A bulky ‘residue’ or carcass of the volume in its binding, after Ege’s extractions, was sold in 1984 and bought through Alan G. Thomas for the Bergendal Collection in Toronto. The 1984 Sotheby’s sales catalogue, which includes a group of various Ege materials left over in his own collection, offers a detailed description.- Sotheby’s, Western Manuscripts and Miniatures, 11 December 1984, lot 52, comprising 125 leaves (some dismembered and loosely inserted) and the 17th-century binding.

Hic liber ad usum Ecclesiae parochalis Sancti Johannis Batistae renovatus est Warburgi anno [1]682, 9 Junii.

This time, the entry places on record the reinterpretation of the place-name from Würzburg to Warburg, located “nr. Paderborn, about 100 miles N.E. of Cologne“. Also:This inscription has previously been read as referring to Würzburg, and it was noted in 1947 that St. Kylian of Würzburg was in the Calendar; however there are many other north German and Rhineland feasts in red too, including SS. Boniface, Odalric, Menulf, 11,000 Virgins [or Saint Ursula and the 10,000 British Virgins], Autbert, etc. The binding no doubt dates from the ‘renovatio’ of 1682.

The entry gives a depressing report of the state of the book.The manuscript is now very imperfect. At least 197 leaves are certainly missing: 50 after f.4, 1 after f.8, 2 after f.9, 3 after f.20, 2 after f.21, 3 after f.22, . . . 1 after f. 61, an unknown number after f. 62, 2 after f. 63, . . . 3 after f. 102, 2 after f.110 and 2 after f.115. In fact, the earliest published description of the volume by Van Ess in 1823 describes it as having 322 leaves. By a neat sum, 322 (1823 description) minus 197 (accounted for missing) is 125 (still present). . . .

Leftovers after the pickings and choosings for Portfolio sets and other vending opportunities take the form of a carcass, after a feast.Part 2: 19 Extra Leaves

A group of 19 detached leaves, sold in 1985, joined the same collection. Apparently as customary, its offering appeared in a Sotheby’s catalogue.- Sotheby’s, Western Manuscripts and Miniatures, 26 November 1985, lot 62, 19 detached leaves, including a large historiated initial B (of Benedicta) for the introit for Trinity Sunday.

— This initial appears among the images displayed in the 2011 Sotheby’s e-catalogue (5 July 2011, lot 87).

The catalogue states that the lot comprises 19 leaves. The Bergendal Collection catalogue calls it 20 leaves (page 4).Parts 1 + 2 = Bergendal MS 69

The resulting ensemble of ‘145’ leaves held the Bergendal number 69. The collection was assembled by Joseph Pope (1921-2010) of Toronto, investor banker and prominent collector of medieval manuscripts. In the survey of the Bergendal manuscripts by William Stoneman for a Festschrift published in 1997 (see above), the entry for this fragment focuses upon the “ex-libris” inscription for Warburg and the stages of transmission of the book through collections subsequently. So far, the catalogue of the Bergendal Collection remains inaccessible for consultation in this time of bibliographical lockdown. Purported links to its presence online (in full or in individual entries) do not function.- Joseph Pope, Bergendal Collection Catalogue: One Hundred and Twenty-Five Manuscripts (Toronto: Brabant Holdings, 1999), number 69.

- Bergendal Collection of Medieval Manuscripts: http://www3.sympatico.ca/bergendalcoll/ (a non-functional link, so that its contents remain unknown)

- F. Dörling (Hamburg), Wertvolle Bücher, Manuskripte und Autographen, Cat. 111 (6–8 June 1985), no. 3. — Teste Gwara, Otto Ege’s Manuscripts, Handlist No. 22 (page 125).

- Sotheby’s, Western Manuscripts and Miniatures, 5 July 2011, lot 87 (145 leaves), viewable via 5 July 2011, lot 87 = olim Bergendal MS 69, within its binding of “early blind-stamped pigskin over wooden boards”.

The text of this large and imposing codex is prefaced by a complete Calendar (fol.1r), and includes parts of the Temporal from the second week of Lent (fol.r) to the twenty-third Sunday after Pentecost (fol.75r); followed by the Canon (fol.76r); and the Sanctoral from the Feasts of SS. Processus and Martinian, 2 July fol.79v), to that of St. Nicholas, 6 December (fol.105v); ending with various masses and prayers.

Present location unknown. Of the historiated or illustrated elements mentioned in the 1947 Sotheby’s catalogue of the Phillipps sale, most of them have left the book, but some have resurfaced. The “ten historiated initials in gold and colours, besides the full-page painting of the Crucifixion” (1 December 1947, no. 92), have been reduced in the Bergendal Portion to the one. That is, the B enclosing an image of the Crucifixion for Trinity Sunday (on “fol.62v”), as illustrated in close-up for the 2011 e-catalogue. Some dispersed leaves, as with the leaf in the Ege Family Portfolio at the Beinecke (Set 3 of FOL; see above), preserve historiated initials, but so far the full-page Crucifixion remains elusive.Würzburg Missal versus Warburg Missal

The 2011 Sotheby’s e-catalogue for the Bergendal Portion records its state at the time as comprising 145 leaves in the restored and partly adjusted binding, with the reused “binding fragments” from another liturgical book (unspecified) having been removed to a “separate” state. The catalogue declares unequivocably that the book wasWritten and illuminated for the use of a priest and choir in a church in the diocese of Würzburg: SS. Kylian, Afra, the two Ewalds, Odalric [Ulrich], Menulf and Autbert in Calendar; and by 1682 in the use of the church of St. John in Warburg, 120 miles south-east [sic!] of Würzburg . . .

Albeit with some refinements (but misrepresenting their geographical orientations), that assessment of origin does not move far from Ege’s Label for the Specimen Leaves from this Missal. As Ege put it,This particular manuscript was written by Benedictine monks for the Parochial School of St. John the Baptist in Würzburg shortly after 1300 A.D .

Thus, Ege conflated provenance with provenience. The conflation seems to have been spurred, at least in part, by the two similarly spelled German place-names, which seem to have challenged accurate transcription in his different versions of Würzburg/Würzberg (see above). Ege supposed that Würzburg had a “Parochial School [sic] of St. John the Baptist” not long “after 1300 A.D.”. He thereby confused a Parish Church (Ecclesiæ parochialis) for a Parochial School. He also presumed the Use of its Missal to be “Benedictine”. As customary for dispersed Ege manuscript fragments (for example, see the Contents List of this blog), it is necessary to examine closely, and often to reasses, the received opinions and assertions regarding them and their original volumes. To cite a few of the challenges which both call for that (re)examination and impede its smooth or swft progress:- the fragmentary and dispersed nature of the evidence, internal to the manuscript and external

- Ege’s unfortunate habits in frequently mis-representing the books by his Labels

- the challenges to rediscovering the dispersed parts of the books

- the difficulties with tracking down the multiple sales catalogues both before and after Ege handled the individual manuscripts

- the multiple, and sometimes contradictory, ways in which institutional collections represent their specimens, in their catalogues and/or online, whether as individual Leaves, in sets of Ege’s Portfolio, or otherwise, sometimes without reporting the connection with Ege.

A Measured Approach

Front Cover for Report by Leslie J. French for the Wagner Leaf from Ege MS 22 (2021)

A Leaf from the Warburg Missal (‘Ege MS 22’) containing part of The Mass for Corpus Christi and its Relation to Other Leaves.

The close examination of selected parts of the text of the Missal — apart from the inaccessible Bergendal Portion — reveals some indications about its specific characteristics, the design for its “use by a celebrant well-versed in both the liturgy and in the performance of the Mass“. It also establishes some directions toward, or indicators for, the possible place (or region) of origin for this Missal. For example,The combined Feasts of 10,000 Martyrs and Albini [Albinus of Angers] in the manuscript are a strong indication of northern-German production. In apparent refutation of that area is the Sotheby’s 1947 Catalog entry stating that St. Kilian is marked in red, and therefore points to a Würzburg provenance. However, this assessment neglects the fact that St. Kilian was also the Patron Saint of Paderborn [in which diocese Warburg belongs]. The Cathedral there is dedicated to Sts Maria, Liborius, and Kilian. There are at least four other churches in the area dedicated to St. Kilian, including one lying between Paderborn and Warburg.

The Wagner Leaf serves as the point of departure and central focus for the Report as well as this blogpost. The generosity of J. S. Wagner in showing it to us, and allowing us to research and to publish it, provided the opportunity to consider Ege’s Manuscript 22 as a complex entity, and to offer reflections based upon our individual and collective explorations of some of its aspects. Drawing inferences about this copy of the Missal, the Report offers observations about its layout, structure, and signs of continued use. The Report then analyzes the textual elements on individual pages of the manuscript (“E”) as compared with other sources. Among them are the printed Missale Herbipolense [Würzburg] (1493), Missale Praemonstratense [Strassburg] (1510), Missale Benedictinum (1481), and several examples of the Missale Coloniense [Cologne] (1481, etc.). The approach applies a method different from the traditional ‘variorum‘ style of edition, listing individual variations at the word level. Because that style — which has merits — “would result in a huge number of apparent variations, obscuring significant differences”, the analysis here “uses instead the individual elements present on the page, and attempts to match the structure between the text of E and the other sources”. This method employs similarity measures — i. e. count, according to Measure Theory. See the Report Booklet. The process and results of the examination offer some caveats and reflections:This report only scratches the surface of the problems, and the pitfalls of liturgical analysis, particularly with only fragmentary, and partly second-hand, evidence. Any one item may be interpreted, or mis-interpreted as leading to a conclusion regarding provenance, date, or Use. . . .

The similarity measures [see above] are also inconclusive. They would seem to rule out the Benedictine Missal as a close relative. . . . The most-likely relatives are the three Missale Coloniense, followed by the Premonstratensian example. Given the relatively low score for the Missale Herbipolense, this is a further indication that Ege’s attribution of origin to Würzburg may not be accurate.

Cologne Cathedral seen from the East. Photo of 21 August 2017 © Thomas Wolf, www.foto-tw.de (CC BY-SA 3.0 DE) via Creative Commons.

A tentative conclusion . . . would favor production, and probable Use, in or near Köln [Cologne], but for an unknown location and purpose. It seems safe at this point to continue to call the manuscript “The Warburg Missal”, pending further evidence.

Further research may resolve some of these and perhaps other questions about Ege’s Würzburg or Warburg Missal.Next Steps

As more leaves come into view, and other features come to be studied in their own right, it might become possible better to understand the nature of this Missal, its history, and its context. Worthy of investigation are, for example, the musical notation throughout the Missal, the individual “masses and prayers” at the end of the Bergendal Portion, and the reused binding fragments which formerly accompanied the volume, or its residue. Similarly, examining the treatment in the Missal of other Saints having centers of devotion in northern Germany might bear fruit, now that other dioceses than Würzburg might beckon for consideration. Examples could include St. Ursula and the 11,000 Virgins, the presence of which in the Missal was noted already in the 1984 Sotheby’s catalogue (see above). The Feast of these Saints on October 21 appears in the Bergendal Portion (current folio number 99). The presumed relics are venerated in Cologne — site of the martyrdom on 21 October 383 — at the Basilica of St. Ursula. An earlier focus upon saints connected with Würzburg, in examining the Missal and its origin, overshadowed attention to saints closely associated with centers elsewhere in northern Germany. It is time to re-examine the case, and perchance to redress an imbalance. As such elements and potential interconnections are taken more fully into account, the Warburg Missal might stand forth more clearly not only as one of Ege’s fragmented books, but also as a witness to the times and places which gave rise to it and through which it (in whole or in pieces) has travelled. Our starting point, the Wagner Leaf, opened an exploration of the manuscript and its evidence, insofar as its leaves and reports present themselves. We look forward to learning more about the book.Further Thoughts?

Front Cover for Report by Leslie J. French for Wagner Leaf from Ege MS 22 (2021)

The combined Feasts of 10,000 Martyrs and Albini [Albinus of Angers] in the manuscript are a strong indication of northern-German production. In apparent refutation of that area is the Sotheby’s 1947 Catalog entry stating that St. Kilian is marked in red, and therefore points to a Würzburg provenance. However, this assessment neglects the fact that St. Kilian was also the Patron Saint of Paderborn [in which diocese Warburg belongs]. The Cathedral there is dedicated to Sts Maria, Liborius, and Kilian. There are at least four other churches in the area dedicated to St. Kilian, including one lying between Paderborn and Warburg.

The Wagner Leaf serves as the point of departure and central focus for the Report as well as this blogpost. The generosity of J. S. Wagner in showing it to us, and allowing us to research and to publish it, provided the opportunity to consider Ege’s Manuscript 22 as a complex entity, and to offer reflections based upon our individual and collective explorations of some of its aspects. Drawing inferences about this copy of the Missal, the Report offers observations about its layout, structure, and signs of continued use. The Report then analyzes the textual elements on individual pages of the manuscript (“E”) as compared with other sources. Among them are the printed Missale Herbipolense [Würzburg] (1493), Missale Praemonstratense [Strassburg] (1510), Missale Benedictinum (1481), and several examples of the Missale Coloniense [Cologne] (1481, etc.). The approach applies a method different from the traditional ‘variorum‘ style of edition, listing individual variations at the word level. Because that style — which has merits — “would result in a huge number of apparent variations, obscuring significant differences”, the analysis here “uses instead the individual elements present on the page, and attempts to match the structure between the text of E and the other sources”. This method employs similarity measures — i. e. count, according to Measure Theory. See the Report Booklet. The process and results of the examination offer some caveats and reflections:This report only scratches the surface of the problems, and the pitfalls of liturgical analysis, particularly with only fragmentary, and partly second-hand, evidence. Any one item may be interpreted, or mis-interpreted as leading to a conclusion regarding provenance, date, or Use. . . .

The similarity measures [see above] are also inconclusive. They would seem to rule out the Benedictine Missal as a close relative. . . . The most-likely relatives are the three Missale Coloniense, followed by the Premonstratensian example. Given the relatively low score for the Missale Herbipolense, this is a further indication that Ege’s attribution of origin to Würzburg may not be accurate.

Cologne Cathedral seen from the East. Photo of 21 August 2017 © Thomas Wolf, www.foto-tw.de (CC BY-SA 3.0 DE) via Creative Commons.

A tentative conclusion . . . would favor production, and probable Use, in or near Köln [Cologne], but for an unknown location and purpose. It seems safe at this point to continue to call the manuscript “The Warburg Missal”, pending further evidence.

Further research may resolve some of these and perhaps other questions about Ege’s Würzburg or Warburg Missal.Next Steps

As more leaves come into view, and other features come to be studied in their own right, it might become possible better to understand the nature of this Missal, its history, and its context. Worthy of investigation are, for example, the musical notation throughout the Missal, the individual “masses and prayers” at the end of the Bergendal Portion, and the reused binding fragments which formerly accompanied the volume. Similarly, examining the treatment in the Missal of other Saints having centers of devotion in northern Germany might bear fruit, now that other dioceses than Würzburg could beckon attention. Examples could include St. Ursula and the 11,000 Virgins. Their presence in the Missal was noted already in the 1984 Sotheby’s catalogue (see above). Their Feast on October 21 occurs in the Bergendal Portion (current folio number 99). Their presumed relics are venerated in Cologne — site of the martyrdom on 21 October 383 — at the Basilica of St. Ursula. An earlier focus for this Missal upon saints connected with Würzburg, in examining the Missal and its origin, overshadowed attention to saints closely associated with centers elsewhere in northern Germany. It is time to re-examine the case, and perchance to redress an imbalance.

Carlo Crivelli, image of Saint Ursula. Outer right wing from the polyptych at the Cathedral of Ascoli. Image Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Further Thoughts?

For now, while continuing to look for reference works still out of reach, or for a glimpse of other parts of the manuscript, we focus on the evidence to hand. Have a look at the free Booklet reporting our research so far. What do you think? Would you like to join the quest? ***** We thank the collector, J. S. Wagner, for bringing his leaf to our attention, and for permitting us to research its evidence and to publish its images. We are grateful to the owners of other leaves from the manuscript, and the owners of parts of other Ege manuscrits, for permission to examine them. We thank Vajra Regan for helping to find access to the Bergendal Collection catalogue. As always, we thank friends, colleagues, and Associates and Trustees of the Research Group on Manuscript Evidence for advice, guidance, and encouragement. Do you know of more leaves from this manuscript? Do you have suggestions for its date and origin? Do you know of other works by the scribes or by the artist(s) of its images? Of other books which formerly belonged to the Parish Church of Saint John the Baptist? Please let us know. Please leave your comments here, Contact Us, and/or visit our Facebook Page. Watch this blog for more reports. See its Contents List. We look forward to hearing from you.

J. S. Wagner Collection, Ege Manuscript 22, Folio clvi, verso: Top. Reproduced by permission.