Medieval Magic in Theory

May 6, 2021 in Abstracts of Conference Papers, Conference, International Congress on Medieval Studies, Kalamazoo, Societas Magica

Medieval Magic in Theory:

Prologues to Learned Texts of Magic

Session Organized by Vajra Regan

***

Hermes Trismegistus. Frontispiece image (Lyons, 1669) via Wikimedia Commons and Wellcome Images.

Session (1 of 3) Co-sponsored by

the Research Group on Manuscript Evidence

and the Societas Magica

at the

56th International Congress on Medieval Studies

(10–15 May 2021)

2021 Congress Program Announced

Congress Session 103, Virtually on

Tuesday, 11 May at 11:00 am EDT

= 2021 Congress Program, pages 38–39

Our plans for this 2021 Session adapt its plan for the cancelled 2020 Congress. Now it is co-sponsored by the Research Group and the Societas Magica, and parts of the contents have been updated.

Scope & Aims

The prologues to medieval texts of learned magic could serve a variety of functions. They were a space for their authors to announce the theme of the work, to situate the work within a specific literary, philosophical, or theological landscape, and to lay special claim to the reader’s attention. Consequently, these prologues have much to tell us about the traditions and beliefs underlying certain magical texts. Moreover, because many magical texts are substantially anonymous compilations, their prologues often provide unique access to the lives and contexts of the men and women behind the parchment.

The aim of this session is to explore these still largely understudied prologues which testify to the variety of medieval approaches to ‘magic’. We are especially interested in how magic is theorized in these prologues. What insights do these prologues offer into contemporary debates about the epistemological status of magic? Moreover, what can they tell us about the social, religious, and institutional contexts of their authors and readers?

Organizer

Vajra Regan

Centre for Medieval Studies, University of Toronto

Program

Presider

Mildred Budny (Research Group on Manuscript Evidence)

*****

1. Papers

Paper 1

David Porreca

Department of Classics, University of Waterloo

“Introducing the Picatrix:

The Prologue’s Balancing Act between Content and Perception”

Abstract

[Also available here: Porecca (2021 (Congress).]

The astral magic text known as Picatrix was the target of substantial opprobrium by many of the intellectual luminaries of the 15th–17th centuries, including François Rabelais, Symphorien Champier, Gabriel Naudé, Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, and Johannes Hartlieb. Although some made profitable use of the text within their own work, they were so concerned about the cloud of controversy surrounding the text that they rarely (if ever) mentioned it by name. (Examples are Marsilio Ficino in De vita libri tres; and the frescos by Cosimo Tura and Francesco del Cossa of allegorical scenes of the Zodiac at the Palazzo Schifanoia in Ferrara). Moreover, the text was popular enough to survive in seventeen complete manuscripts between the 15th and the 17th centuries (in addition to multiple abridged or fragmentary versions), yet it never appeared in print until the 20th century.

The potential for controversy surrounding the text was also known to its original author Maslama bin Qāsim al-Qurṭubī (died 353 AH / 964 CE) and its subsequent translators (into Spanish, 1250’s; thence into Latin, later 13th century). Indeed, the text’s prologue strikes a delicate balancing act between providing the reader with an authentic reflection of its contents vs. trying to allay the negative reaction to said contents that could be expected from an insufficiently prepared readership.

This paper will explore the rhetorical devices, as well as the historical, theological, philosophical, and factual claims made therein, and discuss how that assemblage presents an accurate — yet almost completely whitewashed — picture of the text as a whole. For the most part, the Picatrix falls well beyond the window of acceptable discourse of the 10th–17thcenturies, and its prologue offers a vigorous attempt to distract the reader from that fact.

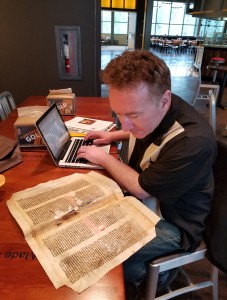

Both Authors at the 2019 Congress. Photography Mildred Budny.

*****

See also:

Picatrix: A Medieval Treatise on Astral Magic, translated with an Introduction by Dan Attrell and David Porreca, based on the Latin edition by David Pingree. Magic in History Series (University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2019).

The Prologue to the Picatrix stands on pages 37–38.

*****

Paper 2

Vajra Regan

Centre for Medieval Studies, University of Toronto

“The Secret in the Prologue to the Collected Treasures:

Biblical Allusions, Occult References, and Coded Language

in a Thirteenth-Century Medical–Magical Lapidary”

Vajra Regan, Inscribed Areola Diagram for Session on ‘Prologues’ (2021)

1) Abstract

[Also available here: Regan (2020>2021 Congress).]

This paper examines three brief prologues all taken from a previously unstudied thirteenth-century medical-magical lapidary. The lapidary is notable for the way it assimilates and reconfigures various texts of Hermetic and Solomonic magic. Although the author has taken pains to disguise his source material, a close reading of the prologues reveals that he has inserted certain clues that point to the magical nature of his work.

Read together, the prologues form a coherent narrative of fall and redemption in which the study of precious stones and their (magical) properties is presented as an accessus to God; however, it is also a narrative in which biblical references alternate, often playfully, with the standard tropes of the Hermetic and Solomonic literature. In this way, the prologues provide a moral and spiritual justification for the study of precious stones while simultaneously alluding to the occult philosophy underpinning the entire work.

2) Handouts

“Having a Look”, at the 2018 Congress. Photography by Mildred Budny.

The 3-page Handout in Latin and English (Handout 1) by Vajra Regan gives the bilingual texts, in the Latin and in his own English translation, of:

- the Preface and Prologue in the Collected Treasures by Bartholomei de Ripa Romea:

Bartholomei de Ripa Romea Contracta thesauria ex philosophie secretis elicita

(“The Collected Treasures of Bartholomaeus de Ripa Romea, Drawn from the Secrets of Philosophy”)

Namely, the Prefatio/Preface to the work; and Prologus/Prologue to its Book I, De coloribus et uirtuibus lapidum (“On the Colors and Properties of Stones”).

- quotations from the Glossa ordinaria and from the Book of Hermes on Alchemy (or Liber dabessi).

The 1-page Areola Diagram (Handout 2 = Handout Copyright Areola) by Vajra Regan, envisions the Areola (Almandal) as described in the Collected Treasures attributed to Bartholomaeus de Ripa Romea.

See Vajra Regan, “The De consecratione lapidum: A Previously Unknown Version of the Liber Almandal Salomonis, Newly Introduced with a Critical Edition and Translation,” Journal of Medieval Latin, vol. 28 (2018): 277–333, with a bilingual Abstract/Resumé via Academia. (Also, The Unknown Liber Almandal Salomonis with Vajra Regan.)

The Areola Diagram is also shown here.

Vajra Regan, Inscribed Areola Diagram for Session on ‘Prologues’ (2021)

*****

2. Response

Phillip A. Bernhardt–House

Skagit Valley College, Whidby Island Campus, and

Columbia College, NAS Whidby Island Campus

(Auto)Biography, Anonymity, and Authority:

Prologues and Their Lack in a Selection of Magical Texts

A Response

Abstract

[Abstract also available here: Bernhardt-House (2021 Congress).]

A “prologue” is another term for what in English is often called a ‘foreword’ in any written work, and can provide many details about the work. These details are often presented in the exegetical formula of tempus, locus, persona, and causa scribendi, but not exclusively nor exhaustively.

In two cases discussed in this Session, we have directly-identified famous historical or perhaps pseudo-historical magicians to whom magical texts are attributed.

- One is Astrampsychos/Astrapsouchos, purportedly a Persian of the time of Alexander the Great, to whom several magical texts including lapidaries and dream books are ascribed, along with a spell in the Papyri Graecae Magicae corpus (PGM), as well as a popular sortilège text which has a short prologue.

- Another is Pachrates/Pancrates of Heliopolis, an Egyptian magician, priest, and poet of the early second century CE. He gave a spell in the PGM corpus to the Emperor Hadrian in circa 130 CE, and wrote an epic poem now extant only in fragments about a lion hunt that Hadrian and his deified favorite Antinous performed. Pachrates also became a literary character in the Philopseudes by Lukian of Samosata in the later second century, and, through this source, has entered posterity as the first literary example of the titular “sorcerer” in the folktale of the “Sorcerer’s Apprentice” popularized by Disney’s Fantasia.

In these cases, are the attributions in these prologues pseudepigraphical or biographical? Or perhaps do they function more along the lines of historiolae that give the magical practices detailed an added efficacy due to their connection with famous magicians who interacted with well-known rulers?

However, some other magical texts have more instructional details or procedural advice and requirements in their prologues, but give no indication of authors or other aspects of the exegetical formula.

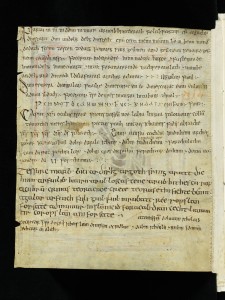

Saint Gall, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 1395, page 419 = verso with the Saint Gall Incantations. Via Creative Commons.

In the case of the early-medieval Irish St. Gall Incantations, surviving in a single manuscript [shown here], there are no attributions of the spells to anyone in particular, whether historical or fictional. This is especially odd, because in medieval Irish manuscripts, poetry is often given an attribution, whereas prose rarely if ever is. As the spells in the St. Gall manuscript (Saint Gall, Stiftsbibliothek, Codex 1395, page 419) often have poetic qualities or forms, this reticence is noteworthy indeed. Not even a mythological personage is mentioned in these texts as the originator of the magical operations, though the spells themselves refer to both Christian and non-Christian supernatural beings. Thus, does this lack and this anonymity serve to highlight the potentially illicit nature of the texts concerned?

By casting one’s net widely and diversely, and juxtaposing these examples with those discussed by the panelists in this session, it is hoped that the purposes of prologues as essential parts of the magical operations themselves can be probed. Such exploration might address the nature of the lapidary text examined by Vajra Regan, and might illuminate how mythological anonymity in relation to magic can serve to distance an author, scribe, and even audience from the negative connotations of magical texts and their contents in the case of the Picatrix, as discussed by David Porreca.

*****

Note:

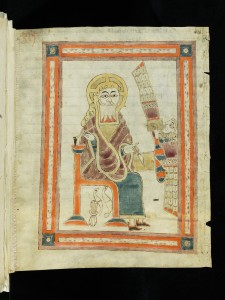

Saint Gall, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 1395, page 418 = recto with a framed illustration of the scribal evangelist Matthew with his winged symbol, a Man. Via Creative Commons.

The “Saint Gall Incantations” survive in one manuscript source now at Saint Gall in Switzerland (shown via www.e-codices.unifr.ch/, specifically at page 419 in a composite volume). Their texts stand on the originally blank verso of a single despoiled leaf. The recto carries an illustration of the Evangelist Matthew as a scribal author. The verso contains the text of the charms in Old Irish, entered presumably within an available space in the original manuscript.

A Session organized by Phillip and co-sponsored by the Research Group on Manuscript Evidence and the Societas Magica included an examination of these text. See our 2018 Congress and Slavin 2018 Congress.

*****

4. Thanks

We thank the Participants for their continuing contributions to Research Group activities over the years, as Organizer, Presider, Speaker, and Respondent. For example:

*****

Hermes Trismegistus. Frontispiece image (Lyons, 1669) via Wikimedia Commons and Wellcome Images.

5. Discussion

We invite questions, discussion, and feedback for the Session on Medieval Magic in Theory: Prologues to Learned Texts of Magic.

Please offer your Comments here, Contact Us, and join the Session online.

- 2021 Congress Program, pages 38–39.

See also our other Activities at the 2021 Congress.

*****