Seminar on the Evidence of Manuscripts (August 1993)

September 11, 2016 in Seminars on Manuscript Evidence, Uncategorized

“British Library, Cotton MS Tiberius A.iii:

An Eleventh-Century Miscellany of Latin and Old English Texts

Owned by Christ Church, Canterbury”

The British Library, 9 August 1993

In the Series of Seminars on the Evidence of Manuscripts

The British Library, London

Invitation in pdf (3 pages including RSVP Form)

The previous Seminar in the series considered

“Corpus Christi College MS 201:

An Eleventh-Century Collection of Homiletic, Legal, and Other Texts”

in Latin and Old English

(Parker Library, 19 June 1993)

[First published on 11 September 2016 by Mildred Budny]

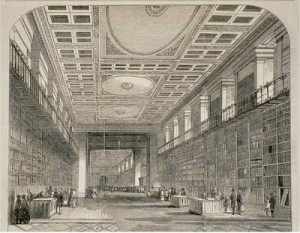

For the first time in this Series of Seminars and other forms of scholarly meetings, a Workshop took place at the British Library, London. Customarily they were held at the Parker Library at Corpus Christi College in the University of Cambridge. Already sessions in the Series had taken place in Oxford (20 June 1992 and 13 March 1993) and in Tokyo (November and December 1993). Now the Series turned to the British Library, as the subject and the opportunity invited.

Organised by Mildred Budny, Malcolm Godden, and Andrew Prescott — all of whom issued the 2-page Invitation Letter — the Workshop at the British Library was designed to gather specialists and students, including some from abroad (Germany, The Netherlands, the United States), who would be attending the 6th biannual conference of the International Society of Anglo-Saxonists (ISAS). That conference took place on 1–7 August at Wadham College, Oxford.

Therefore we planned for “a Saturday before / after ISAS”, and entertained the possibility of holding the event in “Cambridge, Oxford, London”. These logistical considerations are recorded at the head of a 1-page planning outline in the set of 3 undated pages of pencil notes by Mildred Budny within the file for this event in the Research Group Archives.

The selected Saturday suited the speakers whom we hoped to hear and a number of participants whom we hoped to include. The stage was set.

“An Opened Book”

The Manuscript in Place

The 2-page Invitation Letter for the Seminar (shown here and downloadable here with its full-page RSVP form) states the case:

“The subject will be: Cotton MS Tiberius A. iii.”

“This important and controversial manuscript was made in the mid-eleventh century, perhaps at Canterbury. It apparently belonged to Christ Church, Canterbury; it was used extensively by Franciscus Junius; and it suffered damage in the Cotton fire of 1731.”

The Contents

The Letter summarises the components, and their strays into other volumes in the Cotton collection.

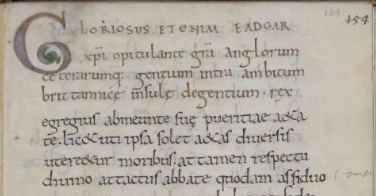

The volume contains a collection of miscellaneous texts in Latin and Old English, including the Regula Sancti Benedicti, supplementary Benedictine texts, the Regularis Concordia, prognostics, confessional prayers and directives, Ælfric’s Colloquy, Ælfric’s De Temporibus Anni, homilies and a unique copy of monasteriales indicia. Some texts have interlinear Old English glosses. Both the Regula Sancti Benedicti and the Regularis Concordia have full-page framed frontispiece illustrations. Folios 174–9 comprise detached leaves from other volumes, including two Cotton manuscripts: Faustina B. iii, fols. 158–98 (an Old English version of the Regularis Concordia); and Tiberius A. vi, fols. 1–35 (the Abingdon version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle). The origin, intentions and use of the miscellany are subjects of considerable interest to Anglo-Saxon studies. The workshop is designed to explore its problems and gather expertise in a wide range of relevant fields.

The Speakers

The Invitation Letter outlines the plan.

“We aim to run the workshop on informal lines, as a round table. This will give plenty of opportunity to respond to the speakers and ask questions. Speakers will include members of the Research Group on Manuscript Evidence and others.

- Helmut Gneuss will speak about the origin and provenance of manuscripts, especially Tiberius A. iii.

- Hans Sauer will consider the makeup of the manuscript and the origin of its texts.

- Mildred Budny will survey the evidence for its Malheimat at St Augustine’s Abbey, Canterbury, through the identification of the artist in other works.

- Andrew Prescott will describe the modern history of Tiberius A. iii (since 1731).

- Lucia Kornexl will examine the interlinear glossing in the Regularis Concordia.

- Rohini Jayatilaka will report on the Regula Sancti Benedicti.

- Debby Banham will discuss the monasteriales indicia.

- Joyce Hill will examine the text of Ælfric’s Colloquy.

- Malcolm Godden will consider the Ælfricean material and its implications for the origin of the manuscript.

As usual, “we hope that others will contribute to the discussion from their areas of specialisation and interest.”

The Setting, Refreshments Included

Page 2 of the Invitation Letter specifies logistics and shows a diagram.

The workshop will take place in the Meeting Rooms on the first floor, Residence 3, in the East Wing of the British Museum, for which a map is enclosed. Coffee will be served from 10:00–10:30. The workshop will begin promptly at 10:30. A sandwich lunch will be provided; if anyone requires different dietary arrangements please let us know. We expect to end at about 5:00. Space is limited so please let us know as soon as possible if you are coming.

About the diagram on Page 2: the Research Group Archives preserve a signed typescript letter of 28 June 1993 from Andrew Prescott confirming and refining elements of the draft invitation (in the form of a 2-page double-spaced dot-matrix printout, in the characteristic medium for the Invitation drafts for the Series). In a series of numbered points, Andrew’s letter addresses details of the date and location; adds to the “list of invitees”; confirms the subject of his own presentation and the availability of “the listed manuscripts”; and appends a 1-page diagram. He explains:

The session will be held in the Meeting Rooms on the first floor, Residence 3 (East Wing of the Museum). I enclose a very rough sketch of the position of the rooms. Perhaps Leslie could produce something more artistic (and more correctly proportioned).

Reviewing the completed Invitation Letter at the distance of more than a decade, as we survey the history of the design and layout by the Research Group on Manuscript Evidence for the record on our upgraded website, it seems useful to observe how the designer of the appearance of most of our publications in any form (including our digital font Bembino) took on the task of rendering the supplied information about directions to the Meeting Rooms into a dramatic diagram immediately recognisable for its place and purpose.

The chosen location also gave the benefit of indirect natural light, on a calm summer’s day in central London, for examining the manuscripts in the flesh (inks, pigments, and wormholes included).

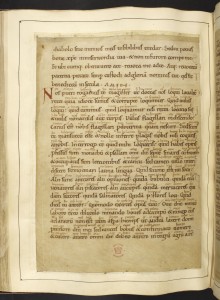

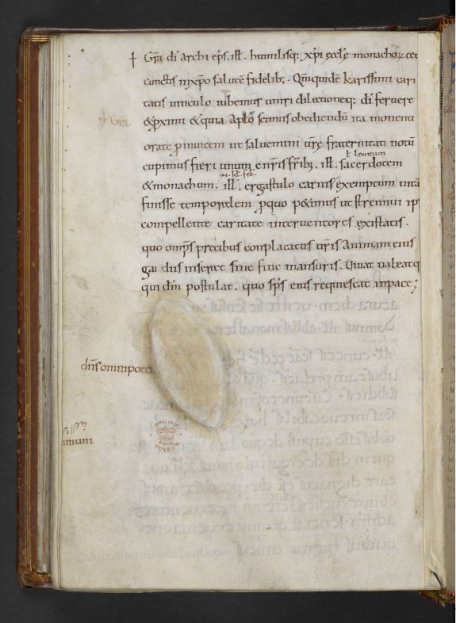

© The British Library Board. Cotton MS Tiberius A III folio 60v. The opening of Ælfric’s Colloquy, plus gloss. Reproduced by permission.

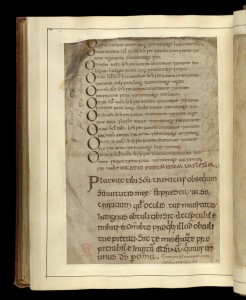

© The British Library Board. Cotton MS Tiberius A III folio 179v. The end of the book, with calendar and prayers. Reproduced by permission.

*****

The Participants

Invitations were sent to:

R.I. Page, Mildred Budny, Nigel Wilkins, Tim Graham, Leslie French, Catherine Hall, Nicholas Hadgraft, Nigel Wilkins, Janet Backhouse, Andrew Prescott, Colin Tite, Nigel Ramsay, Michelle Brown, Robin Alston, Malcolm Godden, Patrick Wormald, Richard Gameson, Rohini Jayatilaka, Debby Banham, Lucia Kornexl, Hans Sauer, Helmut Gneuss, Mechtild Gretsch, Carl Berkhout, William Stoneman, Joyce Hill, Chris Fell.

Present:

A broken leg at the ISAS Conference at Oxford and illness respectively kept Carl J. Berkhout and Debby Banham from attending. From Oxford, Carl sent a letter to be read out, reporting some information which he had discovered. Debby subsequently provided her text on the monasteriales indicia.

*****

The Manuscripts on View

and Under Consideration

Just as the specialists gathered from far and near, so, too, the manuscripts could, by arrangement, join their company and return their gaze. Some of the different manuscripts had formerly, in some measures, belonged to each other, before separation and re-distribution between other sheets and under other covers. In a way, they were rejoining each others’ company, for a few hours, in an assembled company which had some backgrounds to appreciate them.

The Letter confirms that:

MS Tiberius A. iii will be available for examination during the workshop, along with some others in the British Library. They will include

- manuscripts containing illustrations by the same artist (Royal 1 E. vi and Cotton Claudius B. iv)

- manuscripts to which the detached portions belong (Faustina B. iii and Tiberius A. vi)

- and the Christ Church catalogue apparently listing the miscellany (Cotton Galba E. iv).

An extraordinary opportunity.

Manuscripts for Comparison, Contrast, and Companionship

Including Former Parts Reunited — at Least In One Room With A View

Some highlights from the day may come into view here, aided by the current policy for the display of images from the British Library website.

1. The Old English Regularis Concordia

In combination, wormholes, Lawrence Nowell‘s transcript prior to the dismemberment and reshuffling in the Cotton Collection, and other features shared between the 45 leaves of Cotton MS Tiberius A III, folios 174–177 (= “T”), and Cotton MS Faustina B III (= “F”), folios 159–198, attest to their original contiguity. They must have stood in the order F 158 (probably originally a flyleaf), T 174–6, F 159–198, T 177. Here are the first recto and the last verso of the portion of text in the Faustina fragment, which the several leaves in the Tiberius fragment would have “sandwiched”, while the Faustina “flyleaf” would have preceded the whole meal. Food for Thought. Leftovers included.

2. The Frontispiece Artist’s Oeuvre (at the British Library, Anyway)

The meeting gave the chance to see some illustrations in different British Library manuscripts among those which had been attributed to the same 11th-century artist’s hand in a holistic study of one of those manuscripts.

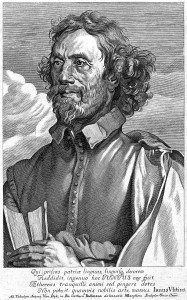

Pigments as a Starting Point

That study, a Ph.D. dissertation for the University of London (1984), concerns British Library Manuscript Royal 1 E.vi: The Anatomy of an Anglo-Saxon Bible Fragment, available freely for download here. Consider especially its pages 73–74 and 236–254, which record the details of shared features between several illustrations in different manuscripts (preserved in the British Library and elsewhere) apparently denoting the work of a single hand. Besides 3 manuscripts from the Royal and Cotton collections now at the British Library, comprising 2 Biblical manuscripts and the miscellany of Tiberius MS A III, the identified group includes 1 biographical manuscript with 2 added frontispiece illustrations now at the Parker Library (Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, MS 389) and perhaps also 1 liturgical manuscript with 2 added frontispiece illustrations now in Warsaw (Biblioteka Narodowa, MS I. 3311).

The Ph.D. dissertation reports how it was the observation of shared pigments that started this part of the quest to understand the nature and evidence of the Royal Bible as a whole in its explorations of the surviving works of Late Anglo-Saxon artists, in connection with the added 11th-century frontispiece in Royal MS 1 E. vi (folio 30v). As part of the research, a comprehensive survey of existing bibliographical accounts of the manuscript brought to light the mention, by-the-way, of an observation by the entymologist and antiquarian John Obadiah Westwood (1805–1893) at proof stage for the publication of one of his own skillfully rendered pre-photographic facsimiles of medieval manuscripts (1868).

Westwood found it appropriate to report, albeit tucked away among the Addenda and Corrigenda, that, at the last-minute state in the production of the book, he had observed a close correspondence between the pigments, and the range of pigments, employed in the frontispiece to the Regula Sancti Benedicti in Cotton MS Tiberius A III (folio 117v) and the added 11th-century frontispiece in Royal MS 1 E VI (folio 30v). To quote that Master (his page 130):

The green and red groundwork of this miniature is shaded all round the figures with deeper washes of the same colours, exactly as in the large miniature of St. Mark . . . from the singular MS. Reg. I. E. 6, with which it also agrees in the long attenuated figure, exaggerated movements of the limbs, treatment of the outlines, and shading of the flesh, so completely, that I have but little doubt that they were executed by the same artist.

© The British Library Board. Cotton MS Tiberius A III, folio 117v, bottom. Reproduced by permission.

The Rest May Follow

Heeding this remark, made by a remarkably keen observer of medieval manuscripts (and other phenomena), inspired our Ph.D. scholar’s request (in the late 1970s) for permission to examine directly both these Reserve manuscripts side-by-side in the Manuscripts Reading Room, with this issue in view. Looking directly, closely, and repeatedly at their images offered affirmation of Westwood’s conjecture, and led to the exploration of other surviving illustrations, including the other illustration in Cotton MS Tiberius A. III. From there, the rest followed.

One of the first blogposts, by that same author, in our series on Manuscript Studies, reflects on this majestic fragment of an Anglo-Saxon Bible and the opportunity to spend years in its company as an introduction to, and center for, manuscript studies across time and place. We may come to think, as she does, of that process as finding, or forming, a ” ‘Foundling Hospital’ for Manuscript Fragments”. Another offering on our website reflects upon the continuing dedication and returns to that research, in a paper presented at one of our New Series of scholarly meetings. The paper, entitled “Still Tied Up in Knotwork,” formed part of the 2014 Colloquium on “When the Dust Has Settled”, with Program Booklet and Abstracts included. (Downloadable here.)

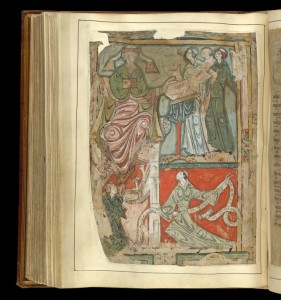

The Frontispieces in Cotton MS Tiberius A III

Originally the 2 frontispieces, and their texts, stood in a different order. We show them here in their former order, with the Benedictine Rule placed before the Regularis Concordia. The sequence was apposite. Not only did the composition (or compilation) of the Rule precede by several centuries the composition and promulgation of the Regularis Concordia, sanctioned at the Council of Winchester around 973 CE, but also the principles and practices stipulated by the Regularis Concordia were grounded in the Benedictine Rule, over and above other Rules for Christian monastic life and rituals.

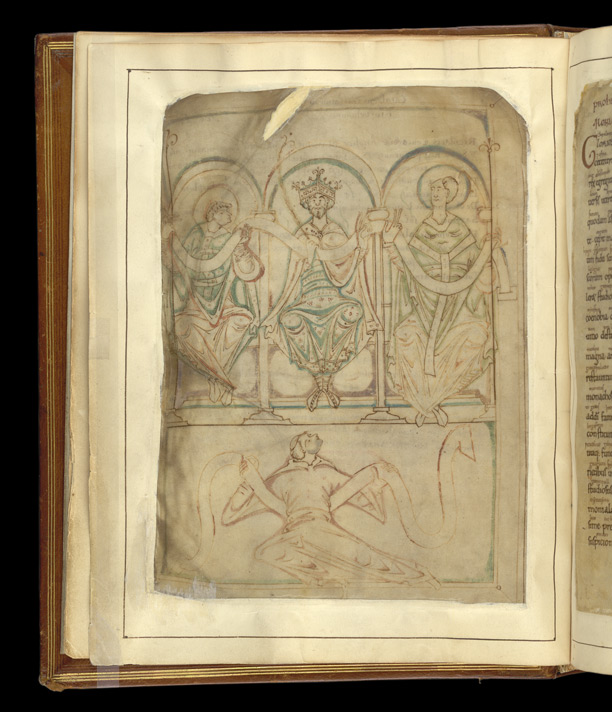

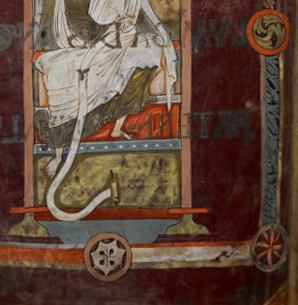

One illustration has inscriptions, the other does not. One is more-or-less finished, with painted figures, furniture, textiles, and settings, as well as ornamented trellis-like frame and inscriptions. The other seems incompleted, with only a few portions painted, and the rest remaining in outline drawing. These differences notwithstanding, the illustrations appear to be the work of a single artist, in different stages of work or work-in-progress.

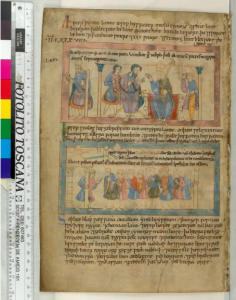

I. Benedict and His Monks Introduce the Regula Sancti Benedicti

The enthroned Benedict (without a halo) sits in frontal pose beside a draped lectern and fingers a partly opened book which lies upon it. At the top right, 3 monks cluster in a group, with an elongated book raised to the right with opened pages facing the observer. In the lower register, 2 monks adopt kneeling or partly kneeling poses, with a long scroll unrolling around the larger, agile monk who dominates that scene. Bookish author, bookish audience, and all seems well with the world — while the Great Fire of London at the Library in 1731 lay far in the future.

© The British Library Board. Cotton MS Tiberius A III, folio 117v, top right. Reproduced by permission.

© The British Library Board. Cotton MS Tiberius A III, folio 117v, bottom. Reproduced by permission.

II. The Authors and Audience Face the Regularis Concordia and Wrap Themselves in Scrolls

Elsewhere in the volume, the 3 promulgators of the Regularis Concordia sit in the niches of a triple arcade in the larger upper register. The crowned and bearded King Edgar takes center stage, with his saints to either side: Bishop Æthelwold at the left and Archbishop Dunstan at the right, identifiable without inscriptions by their episcopal or archiepiscopal vestments and the text which they face across the opening of the book. The lower register barely contains the agile figure of a single monk, who wraps — as if drying — himself in an unrolled scroll. Another partly unrolled scroll winds its sinuous way across the hands of each of the figures at the top. All told, the jointly handled scroll at the top and the wholly embraced scroll at the bottom betoken a shared bond of literacy, with a belief in the power of the written word (and, of course, the Christian Written Word). Given the context of the identifiable figures and the text which they both face and preface, the assemby of figures, gestures, and textual emblems enact a shared adoption of the meaning and impact of those words, as decreed. All may, at least in outline(s) in the partly unfinished frontispiece, make it manifest that all is well with this world, too, following — and Following — the Benedictine Rule, albeit at a different place and for a different text in the volume.

Illustrations Perhaps By the Same Artist

To recap, the workshop gave the opportunity to inspect directly and to compare “in the flesh” 2 more manuscripts from the group of illustrations, made — whether completed or, more often, partly completed — apparently by the same artist, according to our manuscript scholar’s detailed study. At the British Library the volumes are:

- Royal MS 1 E VI

The 9th-century large-format Royal Bible, made and owned by Saint Augustine’s Abbey, with an added 11th-century frontispiece, probably replacing the lost frontispiece or opening page of the Mark Gospel. - Cotton MS Claudius B IV

The 11th-century illustrated medium-format Old English Hexateuch, made and owned by Saint Augustine’s Abbey, with a large cycle of illustrations, some finished and some left in different states of incompletion. Several artists contributed to the work.

1. The Royal Bible of Saint Augustine’s Abbey

The Magnificent 9th-Century Original

& The 11th-Century Add-On

© The British Library Board. Royal MS 1 E VI, folio 30v: Title-Page for the (Lost) Frontispiece for the Mark Gospel.

The added Mark Gospel Frontispiece supplies a filler or substitute for a gap introduced by the spoliation — presumably at Saint Augustine’s Abbey — of parts of the original large-format Bible manuscript. The full-page addition occupies the originally blank verso (folio 30v) of the full-page inscription or caption (folio 30r) which accompanied the original Mark frontispiece (showing the Baptism, according to the inscription), removed during that spoliation and now lost.

The surviving Initial-Page for the Luke Gospel (folio 43r), for example, manifests the superlative artistry of the 9th-century Master Scribal-Artist. Applying paints, including gold and silver, to the purple-dyed parchment leaves posed no failures for that master. That some of the pigments have rubbed away, and that the silver pigment — yes, it is silver — has mostly darkened and spread, halo-like, beyond its original places over time through corrosion and exposure, does not mar the excellence of the craftsmanship, although they do impinge on the original splendour.

Against such standards, “our” 11th-century artist had some handicaps, perhaps largely because of the large size of the page and the dark purple ground. It could be that he used this opportunity, an originally blank page in an earlier, partly despoiled, book, to perform an exercise, trial, or sketch. Whatever the case, he produced an image of the evangelist, monumentally enthroned, turning toward the unrolled scroll for his text as it descends from the extend Hand of God in clouds at the top of his architectural arcade. The winged evangelist symbol, a crouching lion, holds his own scroll between forepaws as he turns toward the other direction within (or mostly within) his own quatrefoil at the top of the panelled rectangular frame for the frontispiece. Divine inspiration and authority for the Gospel text — that is what it is all about.

Illustrations in some other books by, or probably by, this artist manifest some of the same interests, elements, techniques, and approaches. Among other things, to judge by that œuvre, he had a taste for adding to earlier books, adding authors’ frontispieces, adding illustrations to texts, and leaving things unfinished.

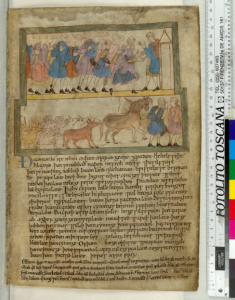

2. The Illustrated Old English Hexateuch

Particularly relevant among the candidates for his surviving body of works, not least for the purposes of our Workshop, appear to be the portions among the large cycle of illustrations in the Old English Hexateuch attributed to the same mid-11th-century artist — an artist active at least at Saint Augustine’s Abbey, to judge by the ownership patterns of some or all of the manuscripts containing his work. (Hence the “confidence” in using the male pronoun for him in our discourse.) According to the attribution of his handiwork (cited above), the portions in the Illustrated Old English Hexateuch involve, for example, folios 68v–69v, 113v, and 142r. We show those pages here.

The set of 3 consecutive pages, all in a row:

And, next, a couple more pages at intervals farther on in the book:

*****

Side-By-Side

Cotton MS Tiberius A III, meet the Royal Bible. All things considered, don’t you think that they look rather well for their age?

*****

Next Up

Next Up

The next Seminar in the Series took place at the Parker Library and focused upon:

“Professionals’ Views of Manuscript Writing:

Calligraphic Techniques in Medieval Manuscripts and Their Modern Descendants”

Parker Library,

November 1993

*****

In Review

The central manuscript and some relatives considered at the August 1993 Workshop figured in presentations and discussions at later Seminars in the Series, especially the Seminar on medieval manuscripts from Canterbury just over one year later.

“Canterbury Manuscripts”

19 September 1994

That Seminar was the last in the Series during the residency of the Research Group on Manuscript Evidence at the Parker Library. It could be no coincidence, given the research interests and focus of the Group, that the first in the Series, held at the Parker Library, devoted to the evidence of manuscript illustrations, featured Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, MS 389 as one of its cases in point:

“Manuscript Illustrations as Evidence of Anglo-Saxon Life”

Parker Library, 20 May 1898

Following the completion of this Series, and the Research Group’s move to the United States in October 1994, there emerged other forms of scholarly events — sometimes over the manuscripts, or some of them, and sometimes not — as reported for our several forms of Seminars, Workshops, Colloquia & Symposia.

*****

Updates

Since the Workshop, there have emerged various publications, including by some of its participants, on the “controversial” Cotton MS Tiberius A. iii. They address, separately or in combination, its language, text, script, glosses, art, structure, ownership, relatives, and more. Because this webpost report reviews the Workshop and its setting, variously on the day, in long-term research, and in the Series, rather than presents a study of the book as such, we do not give a full list of those publications. A few are indicated in some links above, as with the recording of a recitation of Ælfric’s Colloquy (its text appears on folios 6ov–61r; see the image above) through the British Library.

Corpus MS 389 (The Vitae of Eremetical Saints by Saint Jerome and Felix), made and owned by Saint Augustine’s Abbey and augmented there evidently by the same artist as the frontispieces in Cotton MS Tiberius A III, entered the Illustrated Catalogue of Insular, Anglo-Saxon, and Early Anglo-Norman Manuscript Art at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge (2 volumes, 1997) emanating from the long-term, integrated research work on selected Anglo-Saxon and related manuscripts at The Parker Library. Its entry reports updates for the attributions.

Corpus MS 389 (The Vitae of Eremetical Saints by Saint Jerome and Felix), made and owned by Saint Augustine’s Abbey and augmented there evidently by the same artist as the frontispieces in Cotton MS Tiberius A III, entered the Illustrated Catalogue of Insular, Anglo-Saxon, and Early Anglo-Norman Manuscript Art at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge (2 volumes, 1997) emanating from the long-term, integrated research work on selected Anglo-Saxon and related manuscripts at The Parker Library. Its entry reports updates for the attributions.

- MS 389 = Budny Number 23 (The Vitae of Saints Paul and Guthlac by Saint Jerome and Felix)

The stages of the research work are recorded, for example, in the Annual Reports to the Leverhulme Trust, described in our Publications. Many of the catalogue entries, as noted therein, report the results of discoveries and discussions emerging in our series of Seminars, including this one. In that publication, there are gathered entries, and images, from many manuscripts made or owned at Canterbury, in either Christ Church Priory or Saint Augustine’s Abbey, as well as observations relevant to the issues surrounding Cotton MS Tiberius A.iii and its relatives.

The stages of the research work are recorded, for example, in the Annual Reports to the Leverhulme Trust, described in our Publications. Many of the catalogue entries, as noted therein, report the results of discoveries and discussions emerging in our series of Seminars, including this one. In that publication, there are gathered entries, and images, from many manuscripts made or owned at Canterbury, in either Christ Church Priory or Saint Augustine’s Abbey, as well as observations relevant to the issues surrounding Cotton MS Tiberius A.iii and its relatives.

With a change in direction by its co-publisher, the distribution of the Illustrated Catalogue has transferred to the Research Group on Manuscript Evidence. You might enjoy the Promotional Offer.

*****

In Sum (Greater Than The Parts)

© The British Library Board. Cotton MS Tiberius A III, folio 117v, top right. Reproduced by permission.

Many scholars’ and students’ paths may lead to the manuscript, and many paths of inquiry, as well as voyages of discovery, may lead from it.

We had the good fortune to gather around Cotton MS Tiberius A III, and some selected relatives in the form of books, on a summer’s day in London and in erudite, appreciative, company. Not all of us may have been monks, but the attention and collegiality befitted the meeting of minds, both from long ago and from far away.

*****

Next Stop:

Medieval Calligraphy, Then & Now:

“Professionals’ Views of Manuscript Writing:

Calligraphic Techniques in Medieval Manuscripts and Their Modern Descendants”

Parker Library,

November 1993

*****

wonderful post, very informative. I wonder why the other experts of this sector do not notice this. You must continue your writing. I’m sure, you’ve a great readers’ base already!

Thank you so much for your comment! We enjoy hearing from our readers, and appreciate your praise. Best wishes!