A Charter of 1399 from High Ongar in Essex

May 11, 2020 in Manuscript Studies, Uncategorized

A Charter of

23 Richard II (=1399)

Issued on 17 July 1399

at Alta Aungre (High Ongar)

London, British Library, Royal MS 14 E IV, folio 10 recto. “Recueil des croniques” by Jean de Wavrin. Coronation of Richard II at the age of 10 in 1377.

[Posted on 12 May 2020, with updates]

Mildred Budny continues the series of posts on medieval and early modern charters from England in a private collection. See our Contents List.

First we examined the numbered group of documents mainly from Preston in Sussex. Then we turned to documents from other places.

- Full Court Preston

- Preston Take 2

- Preston Charters, Continued

- Charter the Course: More on Preston Charters

- Preston Charters: The Chirographs

- More Light on English Charters

From the Time of Richard II

Once again, we examine a charter from the time of King Richard II (6 January 1367 – c. 14 February 1400), who reigned from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399.

6 Richard II

Previously we considered a charter from this king’s Regnal Year 6, issued at an unnamed location on the Feast of Saint Michael the Archangel, that is, on 19 September 1382. That one is Charter 1 in the numbered series in that private collection which opens the section devoted to English charters. Charter 1 made its appearance in casting More Light on English Charters.

6 Richard II (= 22 June 1382 – 21 June 1383)

“On the Feast of Saint Michael Archangel” = 19 September

I. e. 19 September 1382

Private Collection, “Charter 1”: 6 Richard II Face.

The document retains its original seal, more-or-less intact, with its Legend in Lombard Capitals and its Device in the form of a (partly rubbed) heraldic shield. The Legend begins with a customary star (*) and the word SIGILLUM (“Seal”).

Charter 1: 6 Richard II Charter Seal.

The Document in Question: 23 Richard II from High Ongar

The later specimen from the reign of Richard II which we showcase here is not only later in date of origin, but also a later addition to the private collection; we had the chance to see it soon after its acquisition.

Like “Charter 1”, this document specifies both the Regnal year and a certain day within the year, upon a specific saint’s feast day. Unlike Charter 1, it names its place of issue.

Single Sheet with Tag and Seal

Like all those others in the series (from Full Court Preston onward), this document in Latin on vellum stands on a single sheet. It places the hair-side of the animal skin to the outside, folds its lower edge inward to form a flap, and holds between slits a pendant vellum tag upon which to attach the wax seal.

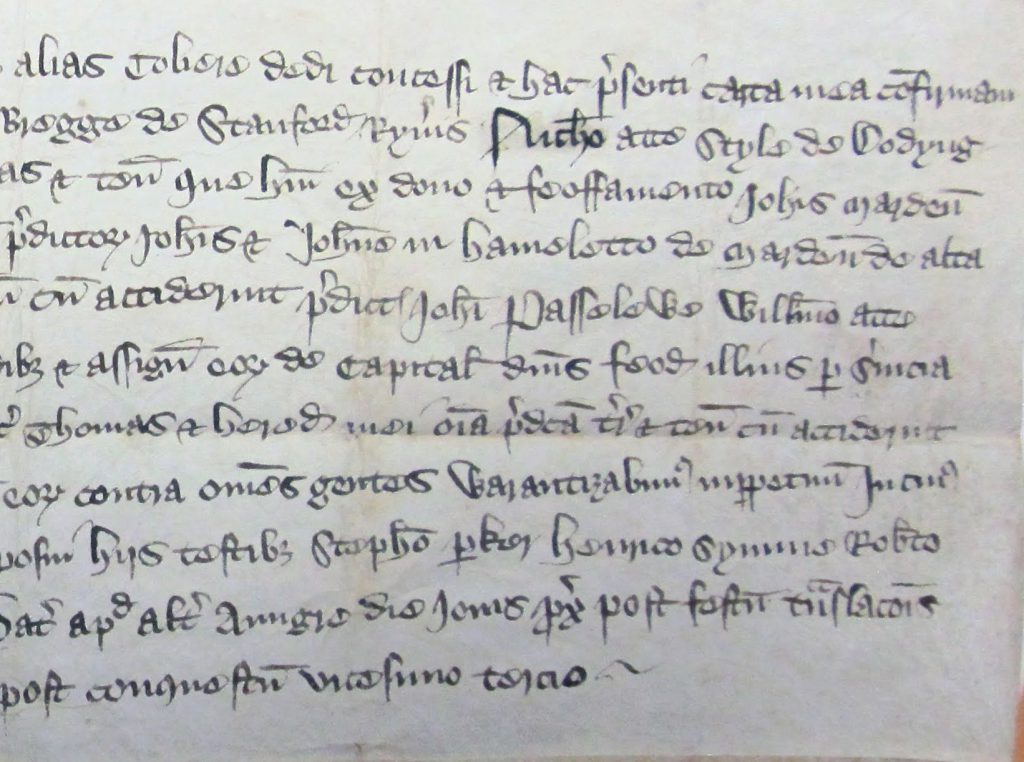

On the face of the sheet, the text forms a single column of 11 long lines, professionally written in Anglicana Formata script. (See another in similar script, by a different scribe: Preston Charters Continued.) The dorse, originally blank, carries a few docketing inscriptions. The uncolored seal survives in part.

Private Collection, Document of 23 Richard II, Face.

The Dorse

The dorse is creased and stained. The fold-lines and their directions demonstrate that the sheet was folded in half horizontally, then into thirds to form a packet, from which the tag extended.

Originally blank, the dorse acquired 3 docketing inscriptions. They stand in a “vertical row”, with their tops turned to the right-hand side of the sheet in one of its folded sections. It would appear that they gathered upon that section as it lay or stood ‘upright’, and with the seal and its tag extending to the right.

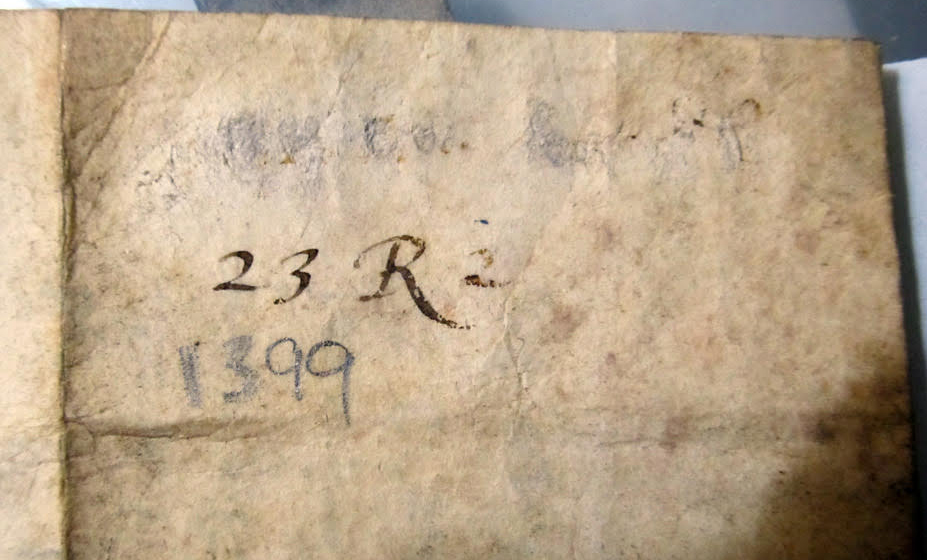

23 Richard II Dorse with Tag and Seal.

The Docketing

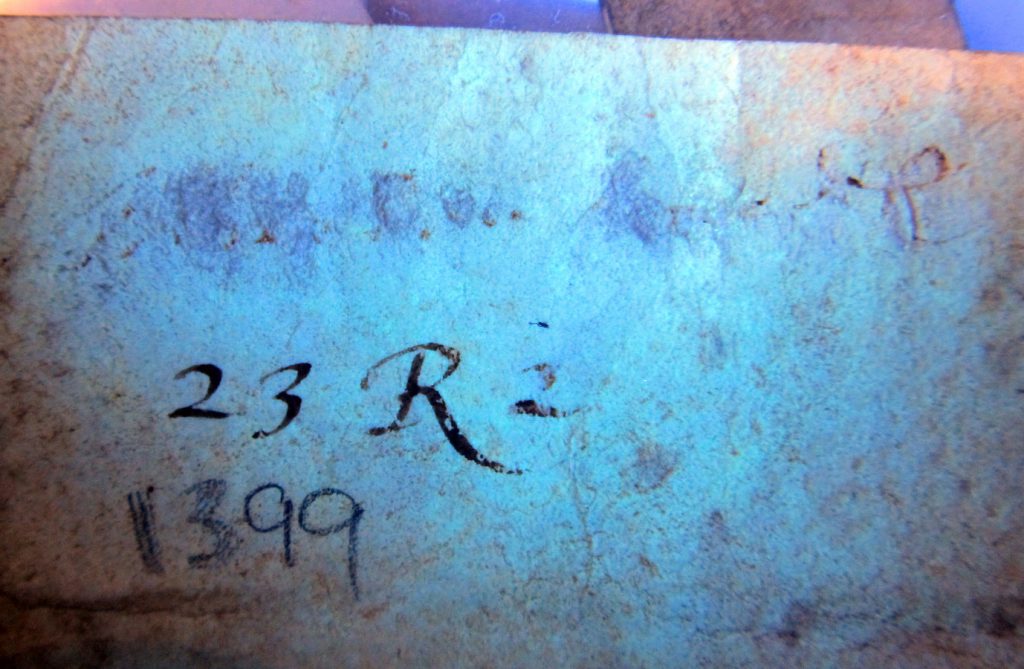

The 3 lines of docketing entries on the dorse include a mostly erased line in brown ink, a statement of the Regnal Year (“23 R 2”) in dark brown ink with arabic numerals, and the date in pencil in arabic numerals (“1399”).

23 Richard II Dorse

Back-lighting reveals a few more traces of the erased inscription and the differences of in width and smoothness between the strokes in the first and second ‘halves’ of the arabic numeral.

23 Richard II Docketing under Back-Lighting.

The Face

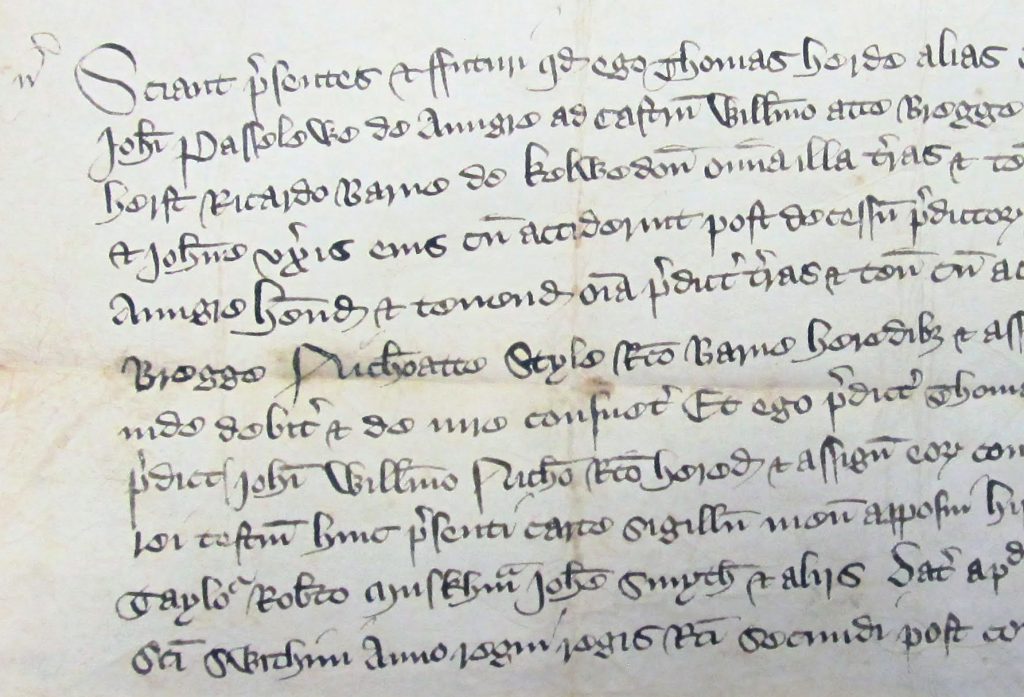

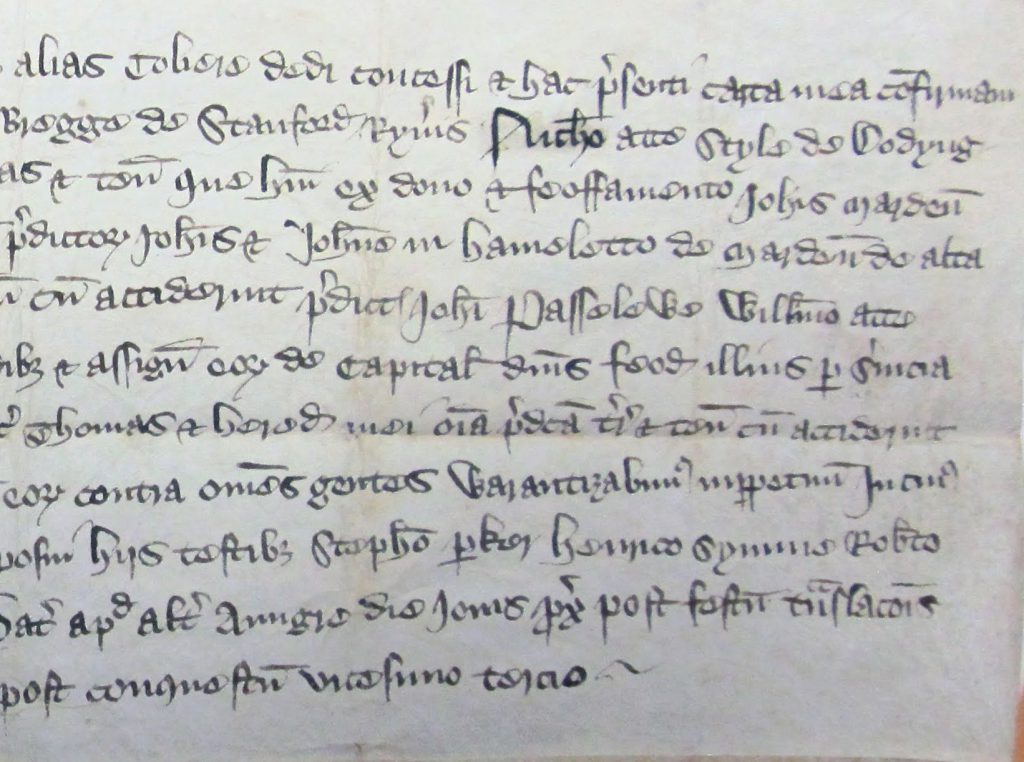

The text is laid out in a single column of 11 long lines written by a single scribe in a professional version of Angicana Formata documentary script (see Charter 6 in Preston Charters Continued). Mostly the ink is light brown in color, but in some places, where the freshly dipped pen left darker strokes, it looks almost black.

Such is noticeably the case in line 2, where one personal name stands out jarringly in darker color than the flow of the script to either side. Perhaps this effect resulted from a space left in the course of the transcription, to be filled upon a return (line 2) once the scribe had ascertained the name of this tenant (Nich’o) among the group of 4.

To the left of the first line and its enlarged initial, there stands a flourished mark, likewise in ink, forming an n-shaped feature rising to a clockwise loop. The text concludes with a separate flourish, which forms an undulating hook-like motif suspended after the conclusion of the text.

23 Richard II Face with Tag and Seal.

The Tag and Seal

Part of the uncolored wax seal survives upon the partly crumpled vellum tag.

Private Collection, Document of 23 Richard II, Tag and Seal.

The wax by now is friable, as a close view shows. To judge by the remnant of the seal, its matrix was round. The imprint of its face retains about half of the rimmed border containing an illegible legend or inscription. At the center the device has an oblong central element of some kind.

23 Richard II Seal Now.

The Script

The document presents its record entirely in ink, the work of a single scribe. It begins with an enlarged initial S which rises both above the line and into the left-hand margin, opening the process with minimum fanfare. Along with such customary features of Anglicana Formata script as a double-compartment a, this scribe consistently used a rounded, closed, theta-like e formed in a single looped stroke, with the tongue descending to the right within the closed bow.

23 Richard II Face: Left-Hand Side.

Of all the enlarged initial letters, the repeated N of the name Nich’o (lines 2 and 6) is both broad and distinctive, with a descending first stem, a slanted top leading to the second stem, and a backward-descending diagonal cross-stroke.

23 Richard II Face

The Text

The text of the document exhibits similar wording and formulae to some charters in our earlier posts. (For example, Preston Charters Continued.) Into such a formula, the scribe would enter the relevant particulars:

Sciant presentes et futuri quod ego . . . dedi concessi et hac praesenti carta mea confirmavi . . . presenta carta sigillum meum apposui hiis testibus . . . Anno regni . . . etc.

Thus, with those ‘supplied’ particulars highlighted here in BOLD, with abbreviations expanded between square brackets ([so]), with superscript letters indicated between inverted commas [‘so’], and with the text transcribed line by line, the document declares:

[Line 1]

Sciant pr[e]sentes et ffuturi q[uo]d Ego Thomas Herde alias Tobere dedi concessi et hac p[rae]senti carta mea co[n]firmaui

Joh[a[n]i Passelewe de Aungre ad Castrum Will[el]mo atte Bregga de Stanford Ryi’r’us Nich[el]o Atte Style de Dodyng[-]

herst R[i]c[ardo Barne de Kelwedon[e] om[n]ia illa t[err]as et ten[ementa] que h[ab]ui ex dono et foeffamento Joh[an]is Marden[is]

Et Joh[a]ne ux[o]’r’is eius cu[m] accederint post decessu[m] p[rae]dictor[um] Joh[an]is et Joh[an]e in hameletto de marden[e] de alta

[Line 5]

Aungre h[ab]end[um] et tenend[um] o[mn]ia pr[ae]dict[as] t[err]as et ten[emena] cu[m] accederint p[raed]ict[i]s Joh[an]i Passelewe Will[e]mo atte

Bregge Mich[el]o atte Style R[i]c[ard]o Barne heredib[is] et assign[antis] eor[um] de capital[ibus] d[o]m[ini]s feod[i] illius p[er] S[e]’r’uicia

inde debit[ur] et de iure consuet[a] Et ego p[rae]dict[us] Thomas et hered[es] mei o[mn]ia p[rae]d[i]cta t[e]r[ra] et ten[ementa] cu[m] accederint

p[rae]dict[is] Joh[an]i Will[el]mo Nich[el]o R[i]c[ar]o heredi[bus] et assign[antis] eoru[m] contra omnes gentes Warrantizabim[us] in p[er]petu[m] In cuius

rei test[i]m[onium] huic p[rae]senti carte sigillu[m] meu[m] apposui hiis testib[us] Steph[an]o P[ar]ker Herico Symms Roberto

[Line 10]

Taylor Rob[er]to Muskh’a’m Joh[an]e Smyth et alis Datur apud alt[am] Aungre die Iovis p[ro]x[ime] post festu[m] t[ra]nslatio[ni]s

S[an]c]t]i Swithini Anno Regno regis R]i]c[ard]i Secundi post conquestu]m] vicesimo tercio.

In Sum

Supplied particulars:

Where & When

23 Richard II (= 22 June 1399 – 29 September 1399)

“On the First Thursday after the Feast of the Translation of Saint Swithin” (= 15 July in England)

I. e. 17 July 1399

at Alta Aungre (High Ongar, Essex)

From

Thomas Herda alias Tobere

What

Omnia terras et tenementa (“All lands and holdings”)

received of the late John Marden and his wife Johanna

in the Hamlet of Marden of Alta Angre

To a Group of 4 Tenants

John Passelewe of Aungre ad Castrum (Chipping Ongar, Essex)

William Atte Bregge of Stanford Ryirus (Stanford Rivers , Essex)

Nicholaus Atte Style of Dodyngherst (presumably Doddinghurst, Essex)

Richard Barne of Kelwedon (Kelvedon Hatch, Essex)

Witnesses

John Parker

Henricus Symms

Robert Taylor

Robert Muskham

John Smyth

Et Aliis

How do we know? Read on, Dear Reader, Read On.

The Day and the Date of Issue

Among Richard II’s Regnal Years, Year 23 was his last, brief, Regnal Year, spanning 22 June 1399 – 29 September 1399. The dating clause at the end of the charter spells it out, as pertaining to Anno regnis regis Ricardi Secundi post Conquestum vicesimo tercio (“in the 23rd year of the reign of King Richard II after the Conquest”).

This clause also specifies the place and the day: Datum . . . die Jovis proxime post festum translationis sancti Swithini (“Issued . . . on the day of the first Thursday after the feast of the Translation of Saint Swithin”). The feast-day of one of the principal English saints, Saint Swithin (circa 800 – 2 July 863), Bishop of Winchester from 852 to 863, is celebrated on 2 July or 15 July, marking the date of his death or the date of the translation of his relics.

The choice of the latter in the document commemorates the translation on 15 July 971 of Swithin’s body to the newly restored basilica at Winchester, newly dedicated to him as its patron saint (in place formerly of the Apostles, Saints Peter and Paul). The Benedictional made for the Anglo-Saxon reformer, Saint Æthelwold, Bishop of Winchester from 963 to 984, for whom the translation was effected, takes care to include an image of this patron among its magnificently illuminated pages. There, the full-page image faces the opening of the text for the celebration of Swithin’s Deposition (2 July).

London, The British Library, Add MS 49598, folio 97v. Saint Swithin. Image Public Domain.

The document of 23 Richard II specifies the Feast of Swithin’s Translation. In 1399, Saint Swithin’s Day on 15 July fell on a Tuesday. The first Thursday after that would have been 17 July. By such calculations can we find the day upon which the document was issued, and not only the year.

23 Richard II Face

Names and Places

The place-name Aungre appears thrice in the document. First it qualifies the name of the first tenant: Johannis Passelewe de Aungre ad Castrum (line 2). Next it refers to a finding point in the boundary clause: in hameletto de marden’ de alta Aungre (lines 4–5). Then it specifies the location at which the document itself was issued: apud alt’ Aungre (line 10).

23 Richard II Face

The name Aungre stands for Ongar (meaning “Grassland” in Old English) in Essex. Aungre is an oft-recorded spelling for that place.

Its appelation ad castrum (“at or by the castle”) relates to Chipping Ongar, which still has a a castle — albeit now in ruins.

Church of Saint Mary, High Ongar, Essex, with 12th-Century Nave. Photograph by John Salmon (8 May 2004), Image via Wikipedia.

The appelation alta (“tall” or “high”) designates High Ongar (see also High Ongar) — at the time probably only a hamlet. High Ongar lies about 1 mile (1 1/2 km) to the south and east from Chipping Ongar.

The “hamlet of Marden of High Ongar” (in hameletto de Marden’ de alta Aungre) appears to have a modern incarnation in Marden Ash, which formerly formed part of the parish of High Ongar. Here “the name Marden goes back at least to the 11th century and means ‘boundary valley’: it suggests that this was the boundary between Chipping Ongar and High Ongar even at that time”.

— — P. H. Reamey, The Place-Names of Essex. English Place-Name Society, Vol. 12 (Cambridge: At the University Press, 1935), page 73; also British History Online: High Ongar.

In this context, it may accord with long-standing practice that the document locates boundaries with reference to Marden as one of them.

Stanford Rivers is also near by, only about 2 miles (3 km) south of Chipping Ongar. The common place-name Stanford derives from “a stone, or stony, ford” in Old English. A Stanford survives in Norfolk as a deserted village. As with some other Stanfords, the place called Stanford in the document both received and retained an appelation. Stanford Rivers is listed in the Doomsday Book as Stanfort, but in 1289 as Stanford Ryueres, adopting the name of the 13th-century manorial family Ryueres. See, for example, Anthony David Mills, A Dictionary of British Place Names (Oxford: Oxford University Press, revised edition, 2011: ISBN 019960908X ), p. 432. The document spells the name as Ryi’r’us (line 2), with a superscript r between the 3 minims (i and u); a similar superscript r stands above ux’r’is in line 4.

Dodyngherst is presumably Doddinghurst, in Essex, to the southeast of High Ongar and close to Stanford Rivers. Across time, its recorded spellings varied, for example with Duddingeherst in 1218. Pertaining to an early layer of Old English place-naming patterns in the early medieval migrations to England, the Old English name means “the wooded hill of Dudda‘s people”. (For example, the Dictionary of British Place Names, page 146.)

Richard Barne of Kelwedon came also from Essex. Villages in Essex among medieval settlements still extant with such a name are Kelvedon (Kelvedon) in northeast Essex and Kelvedon Hatch (Kelvedon Hatch). The latter stands within the Hundred of Ongar and considerably closer than the former to the other places cited in the document, pertaining to Aungre in its several manifestations, both on higher ground and near a castle, and now known as High Ongar and Chipping Ongar. Kelvedon Hatch lies 3 miles south of Chipping Ongar.

The Hundred of Ongar comprised 26 parishes, including Kelved Hatch, Stanford Rivers, Cheping Ongar, and High Ongar. Some Ongar parishes are picturesquely described and illustrated in “The Hundred of Ongar” by the English antiquary Elizabeth Ogborne (1763/4 – 1853) in The History of Essex from the Earliest Period to the Present Time (London: R. H. Kelham,1 814), pages 235–280, with the full list of parishes on page 236. The subtitle of this work advertised it as being Illustrated with accurate Engravings of Churches, Monuments, Ancient Buildings, Seals, Portraits, Autographs, &c., With Biographical Notices of the most distinguished and remarkable Natives. Alas, the work was unfinished, with only Volume I, in which the illustrated descriptions of the individual parishes of this Hundred cease before they reach any of those names within whose reach the place-names of the document come to rest.

Spellings very similar to those in the document are recorded in the Essex Poll Tax for 1377, which dates only some 20 years earlier. The modern edition of that record notes the modern equivalents.

- Stanford Rever = Stanford Rivers

- Alta Aungr = High Ongar

- Kelwedon = Kelvedon Hatch

- Aungr ad Castrum = Chipping Ongar

— — The Poll Taxes of 1377, 1379, and 1381, Part I: Bedfordshire–Leicestershire, edited by Carolyn C. Fenwick. Record of Social and Economic History, New Series, 37 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998–2005), “Essex 1377: Ongar and Rochford Hundreds”, at E179.

Such close, and even precise, correspondences for the individual place-names — as their records adapted across time — and for the cluster of names recorded within the transaction appear to establish their identities in the document beyond doubt as pertaining to the Hundred of Ongar in Essex.

23 Richard II Face: Text.

Location, Location, Locations

These places, with a few variants in spelling, appear on Old Maps of Essex, available among the Old Maps Online and other digital resources:

- Map of Essex among the 35 colored maps published by Christopher Saxon in the Atlas of England and Wales (1579).

- Interactive version of the Map of the County of Essex from the atlas of 25 engraved sheets by John Chapman & Peter André (1777).

- Map of Essex actually surveyed with the several Roads from London, etc. (London [1678]).

The latter, via Public Domain, comes from the Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library:

![Boston Public Library, Map of "Essex actually surveyed with the several Roads from London, etc." (London [1678]), Image via Public Domain.](http://manuscriptevidence.org/wpme/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/commonwealth_ww72bp422_productionMaster-at-180-dpi-1024x814.jpg)

Boston Public Library, Map of “Essex actually surveyed with the several Roads from London, etc.” (London [1678]), Image via Public Domain.

![Boston Public Library, Map of "Essex actually surveyed with the several Roads from London, etc." (London [1678]), Detail of Ongar Hundred. Image via Public Domain.](http://manuscriptevidence.org/wpme/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/commonwealth_ww72bp422_productionMaster-to-Ongar-Hundred-897x1024.jpg)

Boston Public Library, Map of “Essex actually surveyed with the several Roads from London, etc.” (London [1678]), Detail of Ongar Hundred. Image via Public Domain.

The Transaction as Record

From its details, the document yields information about a set of individuals and their interrelationships regarding landscapes, both which they have been associated — Aungre ad castrum, Alta Aungra, Stanford Ryirus, Dodyngherst, and Kolwedon — and over which they formally transfer custodianship on Saint Swithin’s Day, 1399. In the case of the land at the center of the transaction, we learn also about its previous transfer (at an unspecified date) from a named couple after their death.

Private Collection, Document of 23 Richard II, Tag and Seal.

*****

Do you recognize other examples of this scribe’s work? Do you know more about the history of these features, places, and persons?

Please contact us via Contact Us or our Facebook Page. Comments here are welcome too.

*****

More to Come. See the Contents List for this blog.

*****

P. S. On a Personal Note (17 May 2020). Although I don’t remember if I visited any of the places mentioned in the document, I vividly recall visiting Greensted close by. The purpose of the visit was Greensted Church, located about one mile west of Chipping Ongar town center. My interest resided in seeing the wooden structure of the building, because of its age and its Anglo-Saxon construction.

This was while I lived in London and engaged in long-term postgraduate study of Anglo-Saxon and related manuscripts and their broader context — leading from the M. A. in English Language and Literature before 1525 (University of London, 1972) to the Ph. D. in Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts (London, 1985). An important component of the research was travel to examine material evidence first hand.

It was natural that part of the observation attended to building structures, given their settings for the production, viewing, and use of the manuscripts and other media, and given my studies in seminars with archaeologists and building historians, among others. Apart from archaeological excavations and ruins, many of the viewing opportunities allowed for more imposing architectural structures, but I wished also to see the “only remaining example of the many timber churches” of the Anglo-Saxon period before the Norman Conquest, as Greensted Church is described in a standard reference work on the subject.

— — H. M. and Joan Taylor, Anglo-Saxon Architecture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 3 volumes, 1965 and 1978), Volume 1, pages 262–264, at page 263.

North Side of Wooden Church at Greensted-juxta-Ongar, Essex. Photograph by Simon Garbutt via Wikimedia Commons.

The Church of Saint Andrew at Greensted is regarded as “the oldest wooden building in Europe still standing, albeit only in part, since few sections of its original wooden structure remain”. The nave, made of large split oak tree trunks, is mostly original. The official name of the place is Greensted-juxta-Ongar (“Greensted adjoining Ongar”), to distinguish it from another Greenstead, also in Essex, but some 30 miles distant, in Colchester.

My visit took place on a sunny day, in a day trip by car from London. I forget which year, but having a car places the date in the later 1970s. I remember well the warm sunshine outside the building and the dark wooden interior, so it would probably have been in the spring or summer. There are photographs from the visit, so others’ available photographs might serve.

From the distance of this blogpost, I survey the distance travelled across time and space by the document from its origins in Essex to my view of it as it first entered its current collection in the United States several years ago, and by my understanding of the subjects from immersion in study for the M. A. onward. The “papers” selected for that M. A. in London were dedicated to Language, Palaeography, Archaeology, and English Place-Names.

In all the travels and studies over the years devoted to such subjects (see, for example, Her Page and (Selected Publications), I might not have guessed that they would have come to include a close look at place-names centered upon one of the central areas of Ongar Hundred.

*****