Another Witness to the Cistercian Statutes of 1257

December 2, 2016 in Manuscript Studies, Photographic Exhibition

Part-Leaf from a Dismembered Witness

Part-Leaf from a Dismembered Witness

to the 1257 Codification of the Statutes

for the Cistercian Order

A Part-Leaf, now on its own, carries parts of the Chapter De Conversis (“On the Lay Brothers”)

from Distinctio (“Section”) XIV (out of XV in total)

in the Codification of 1257 of Statutes for the Cistercian Order

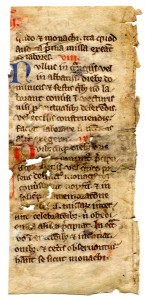

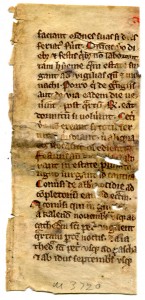

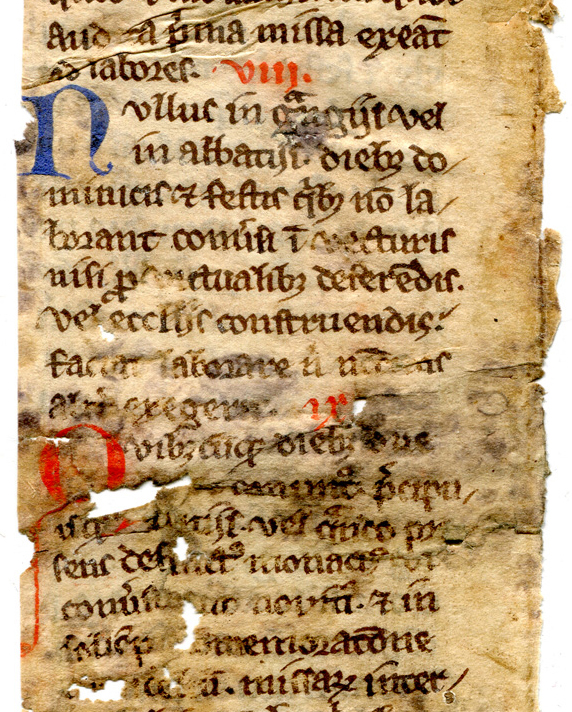

This installment of our blog on Manuscript Studies identifies a fragmentary 13th-century leaf on vellum with monastic rules in Latin. Now reduced to a single column of its original double columns of text, the fragment carries parts of the Statutes of the Cistercian Order, in a mid-–13th-century version — or, rather, extension — of those Statutes. That extended version appears in full in a few other extant manuscripts. Mildred Budny describes the fragment and its testimony.

Fragmentary Leaf with

Parts of the Chapter De Conversis (“About the Lay Brothers”)

from Statutes of 1257 of the Cistercian Order

Circa 142 mm × 61 mm (from crease to cut edge)

< written area circa 115 mm × 50 mm >

Formerly in double columns of 28 lines

with bichrome embellishment

in running titles, rubricated titles, and section initials

Most of 1 column and parts of the margins

survive on each side of the Part-Leaf

A Leaf Converted

Now in a private collection, a fragment of a leaf in Latin on parchment or vellum survives from a text originally laid out in double columns of 23 lines. Of those columns, only the inner column (a or b) survives on each side (of former columns a–b). That is: there remain column a on the recto and column b on the verso.

The Recto: Column A (= “ra”)

The Verso: Column B (= “vb”)

The remnant carries parts of the text of Chapter XIV, De Conversis (“On the Lay-Brethren”), the penultimate chapter of a mid-13th-century version or extension of the Statutes of the Cistercian Order of monks and nuns— a religious order which continues to have an active life worldwide. To judge by the 19th- and 20th-century editions of those 13th-century Statutes (see below), there survive apparently a few manuscript witnesses, from France and elsewhere, to which can be added the manuscript from which “our” fragment derives.

It is a shame that its manuscript was dismembered and dispersed — and without suitable documentation.

Information Tags for Manuscript Orphans

We recognize that sellers may have reasons, for whatever reasons, for wishing to keep their sources and their own locations anonymous. It could nevertheless be useful to relate some elements which might have nothing to do with such tell-tale give-aways, but which could allow our wider knowledge to have some authentic clues from the intermediary. Such clues could guide assessments of the materials by ruling out some speculations that might not have any relevance, should we know such.

To draw an example out of nowhere and anywhere:

This leaf was found in a family’s heirloom box of many fragments and documents which came from one place [Name supplied if deemed appropriate]. We obtained only 1 of them [Or all of them]. The leaf [or whatever] was on its own. [Or: had a mat, which we removed / came in a frame / contained a sheaf of XYZ contents which stayed behind for the family collection / had a damaged tag which was lost in the move from there.]

You get the picture?

About the issue of irresponsible fragmentation and distribution of manuscripts (of whatever date, medieval included), we have strong views. Some posts for this Blog on Manuscript Studies state them. Examples include The ‘Foundling Hospital’ for Manuscript Fragments and Lost and Foundlings.

The Cistercian Order

The spread of the Cistercian Order was impressive.

The expansion of the Cistercian Order by the end of the 13th century. Map by Chabacano via Creative Commons.

Among the new religious orders emerging in Western Europe in response to increasingly vociferous demands for reform in the Church in the 12th century, the Cistercian Order (or Ordre cistercien) was among the most important — and, or (which may be the same thing), long-lasting. Called “White Monks” from the color of their white choir robe (cuccula) worn over their habits, Cistercians rose to prominence in spreading new monastic foundations in Europe, as their Order spread swiftly from its origins in Burgundy throughout France, Britain (all over), the Iberian Peninsula, Italy, and beyond. (See map.)

The Cistercian way of life emphasized solitude and isolation. Work, too, along with a strong measure of self-sufficiency. Guided by an ideal of individual poverty as well as a readiness to pursue collective endeavor, including manual labor, Cistercian monks held no personal property, while they worked the land and other resources. The plan worked, too.

As grants of lands extended the domains, with endowments sufficient to support the communities, the movement grew, and with it the requited need for Rules. Benedict, presumably, would have approved.

Rules to govern the internal affairs of each monastery might be one thing. Living larger, the Cistercian Order as a whole was regulated by statutes produced at Cîteaux in Burgundy, the mother-house of the Order.

And the Statutes Kept On Coming, Revisions and Updates Included.

Origins and Transmission

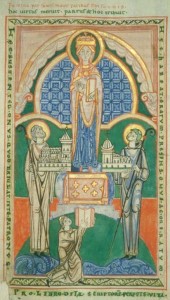

Stephen Harding presents a model of his church to the Virgin Mary. Dijon, Bibliothèque municipale, MS 130, folio 4r. Saint-Vaast d’Arras, circa 1125. Photograph via Wikipedia Commons.

The Order traces its origins to the foundation in 1098 of the monastery or abbey of Cîteaux, south of Dijon in Burgundy, France. Seeking more closely to follow the Rule of Saint Benedict — constructed, or at any rate, effectively promulgated, by Saint Benedict of Nursia (circa 480–550), or by someone else, whose identity remains unknown — a group of monks set out from Molesme Abbey also in Burgundy; choose a wooded, swampy, and scarcely populated area; founded their new abbey on the Feast Day of that Saint Benedict (21 March); and submitted to its first abbot, Robert of Molesme (1028–1111). Among these founders was the widely-traveled, many-faceted, multilingual Englishman Stephen Harding (died 1134). Such beginnings demonstrate the broad, yet focused, horizons of the movement as it launched its journey across time.

The rest is History. Writ large, even.

Admiring the momentum of this accumulated movement across regions and generations, and many of its monuments in stone and other media, let us pause to focus upon the bit of a leaf from a version of its Statutes. The fragment has a place for its testimony in the course of history. Here is its moment, or, perhaps, the first of such moments which it may attain.

Cistercian Studies

Studies of the Cistercian Order, its origins, context, history, impact, and continuing vitality are many. They appear in various languages, in various degrees of detail, both in print and online. A few references, online and in print, might set the stage for exploration.

- Stephen Tobin, The Cistercians: Monks and Monasteries in Europe (1995)

- EuCist News: News on Cistercian Research (2009–)

- Mette Birkedal Brunn, ed., The Cambridge Companion to the Cistercian Order (2013).

As an indicator, rapid glimpses of the different-language versions of the entry for Wikipedia reveal varying lengths, selected images, and points of emphasis appropriate in part to their centers of attention or concern. For example (for starters), in English, French, Italian, Spanish, German, Dutch, Polish, Hungarian:

- Cistercians

- Ordre cistercien

- Orden del Císter

- Ordine cistercense

- Zisterzienser

- Ciszterciek

- Cystersi

- Cisterciënzer

Codifications of the Rules: Statutes and Revisions

The earliest Statutes of the Cistercians have received monumental scholarly attention. Among the many sources and discussions published, disseminated, and reviewed, a selection of works here might provide directions toward the massive bibliography, along with some complex guidance to the manuscripts which transmit those early Statutes.

Consider the group of editions and studies by the Cistercian monk and scholar Chrysogonus Waddell (1930–2008):

- Narrative and Legislative Texts from Early Citeaux: Latin Text in Dual Edition with English Translation and Notes.

- Cistercian Lay Brothers: Twelfth-Century Usages with Related Texts.

- Twelfth-Century Statutes from the Cistercian General Chapter: Latin Text with English Notes and Commentary.

They belong to the series Studia et Documenta, Volumes 9, 10, 12: Citeaux: Comentari Cisterciensis (1999, 2000, and 2002).

Let us not forget the study of the intricate evolution of the early foundational documents of the Order by

- J.B. Augerger, Histoire des textes primitifs. Les plus anciens textes cisterciens (1986).

Nor should we ignore the detailed examination, plus edition, of some somewhat Later Statutes of the 13th century and their contexts, for example by

- Joseph Thomas Fowler, Cistercian Statutes: With Supplementary Statutes of the Order, AD. 1257–88, Volumes IX, X, and XI, spread out in a series of ‘Parts I–[VII]’ (See below)

- Bernard Lucet, Les codifications cisterciennes de 1237 et de 1257.

Sources d’histoire médiévale publiées par l’Institut de recherche et d’histoire des textes (1977), for which there is a convenient review.

[This book, requiring one-or-another form of “Pay To Play” (i.e. access), became available for consultation only after the principal work of my investigations for the “new” manuscript fragment had advanced.]

Studies of the somewhat Later Statutes appear to be few and far between. Where they do emerge, they can be hard to find, and they can require paid access in one form or another (not available or readily available to all of us). Moreover, even when they do emerge in publication, they might not “talk to each other”or take account of one another — to the detriment of progress in shaping or refining knowledge of the evidence. As witness the information-lag between the studies conducted respectively in England and France, and in English and French, in the late 19th- and early 20th centuries, as lucidly described by Lucet (1977), pages 54–56.

The Charter of Charity and Beyond

An English translation of the early Statutes or Constitution of the Cistercian Order, also known as the C(h)arta C(h)aritatis (“The Bond of Love” or “The Charter of Charity”), appears online.

The text of the Carta Caritatas, probably assembled in 1114 when Cîteaux founded its second daughter house at Pontigny, regulates relations between Cistercian houses, according to the mutual love that should bind them together; apparently no manuscript of this version survives. A somewhat later version, known as the Carta caritatis prior (“The Earlier Charter of Charity”), approved in 1119 and composed by Stephen Harding, third Abbot of Cîteaux (died 1135), functions as the Constitution of the Order. Then came the Carta caritatis posterior (“The Later Charter of Charity”), composed between 1165 and 1173; it remains the basis of the Constitution of the Cistercians today.

Further codifications of the rules of the Order followed in stages, for example in 1237 and 1257, arising from the annual modifications, from 1220 onward, by the General Chapter. The Statutes of 1257 preceded the bull Parvus fons of 1265 by Pope Clement IV (pope from 1265 until his death in 1268). That intervention more-or-less settled the internal quarrels between the rival Abbots of Cîteaux and Clairveau over the authority to make appointments to the diffinitiorium, which functioned as a steering committee of the General Council of the Order.

Complicated, huh? To be expected, probably, with the rapid spread of the Order into different regions and time-periods.

Manuscripts of the Statutes for Online Viewing

Examples of digitally-viewable manuscript witnesses to the Statutes in various states of evolution include

- a copy at Yale of circa 1200 perhaps from Fitero Abbey in Navarre (between Pamplona and Tudela), Spain, and

- a Libellus statutorum Cisterciensis ordinis (known as “The Book of Old Definitions”) copied after 1316–1317 (with the Posterior version) from the Abbey of Notre-Dame de Loos in Flanders.

Manuscripts of the Libellus of 1257

Bernard Lucet’s edition of 1977 of the “Codification de 1257” of the Cistercian Statutes draws upon 8 medieval manuscripts. They are described on his pages 41–73, provided with distinguishing sigla, listed on page 204, and printed on pages 205–357, in tandem with the earlier Libellus of 1237 (drawn from 6 manuscripts).

These witnesses to the 1257 Libellus (“Little Book” or “CaseBook”) are, with Lucet’s sigla:

- “MS P” = Poitiers, Médiathèque François Mitterrand, MS 128

Made in the second half of the 13th century, datable to 1257–1259, and owned by L’Étoile Abbey - “MS B” = Brussels, Koninklijke Bibliotheek België, MS 19051

Made in the second half of the 13th century, circa 1260 - “MS F” = London, British Library, Additional MS 11294

Made in the second half of the 13th century, owned by Fontenay Abbey,

edited by Fowler (1886–1889), and integrated into French studies of Cistercian Statutes only much later than Fowler’s work - “MS Fd” = Frauenfeld, Kantonsbibliothek Thurgau, MS Y 38a (not yet online).

Made in the 13th century and owned by Salem Abbey in the district of the Bodensee - “MS H” = London, British Library, Harley MS 3898.

Made in the 13th century and owned by a Cistercian Abbey in the diocese of Liege

(the 3 candidates there are the Abbeys of Aulne, Val-Saint-Lambert, or Le Val-Dieu) - “MS L”= Laon, Bibliothèque Municipale, MS 333.

Made in the second half of the 13th century, and owned by the 18th century by Vauclair Abbey - “MS Pa” = Pavia, Biblioteca Universitaria di Pavia, Fondo Aldini MS 470.

Made at the end of the 13th century, and owed by an Italian Cistercian Abbey as yet unidentified - “MS S” = Stams, Stiftsbibliothek, MS 38

Made in the 14th century, and owned by Stams Abbey in the Austrian Tyrol, but now reduced to a mutilated copy

Because Lucet’s publication did not become accessible to me, despite repeated efforts, until an advanced stage in my research on the New Fragment, it was necessary and possible to progress on the basis of Fowler’s edition, flawed as it is in certain respects. However, we progress as we can. Progress can be good — provided, of course, that it constitutes progress.

The Partial Witness

To put it another way. A fragmentary 13th-century leaf, now in a private collection, with monastic rules in Latin, carries parts of the Statutes of the Cistercian Order, in a 13th-century version as edited by Joseph Thomas Fowler in stages in the Yorkshire Archaeological and Topographical Journal, volumes IX–XI (1885–1890).

Fortunately the edition is freely available online: Joseph Thomas Fowler, Cistercian Statutes: With Supplementary Statutes of the Order, AD. 1257–88, Volumes IX, X, and XI, spread out in a series of ‘Parts I–[VII]’. Citations to it are tricky (for which read “inconsistent”), so that it could be helpful for some readers to clarify the locations of the individual Parts. To whit:

- Volume IX, pages 223–240 and 338–361

Parts I and II - Volume X, pages 51–62, 217–233, 388–406, 502–522

Parts III–VI - Volume XI, pages 95–127

‘Concluded: Statutes of 1257–88, being Supplementary to those of 1256–7, printed above’

Fowler’s apparently rarely consulted edition is admittedly based upon one manuscript now in the British Library: Additional MS 11,294 (not yet available online). It came from the library of the Cistercian Abbey of Fontenay, founded in 1118 by Saint Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153), and located in what is now the Département of the Côte-d’Or in France.

Abbaye de Fontenay (Marmagne, Côte-d’Or, Bourgogne, France), Interior View of the Abbey Church. Via Wikipedia Commons

The Long Way Home

Fowler’s edition (not exactly a model of impeccable elucidation) reproduces the portions which extend the earlier Statutes of the Cistercian Order — for which there are detailed editions and elaborated studies (see, for example, above) — by adding Statutes respectively of these years:

- 1256–57 CE and

- 1257–88 CE.

As found on folios 25–36 of the manuscript witness. The complicated contents of the manuscript are listed by Lucet (1977), pages 50–54.

The text on “our” leaf corresponds with parts of the penultimate Distinctio (“Section”) of the Statutes of 1256–57, that is, Distinctio 14 out of 15 Distinctiones.

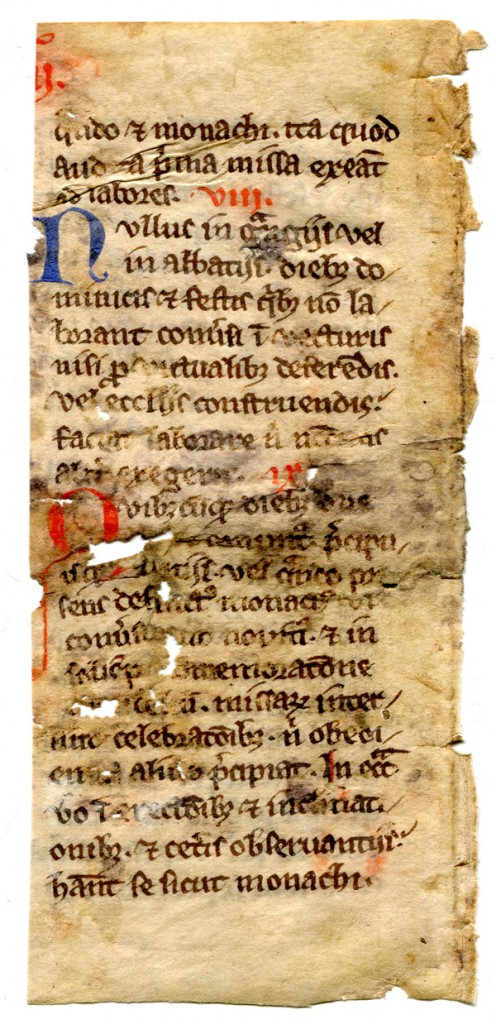

Fragment from the Past

Purchased some years ago from the dealer Boyd Mackus, the fragmentary leaf is now in a private collection. The pencil item number ‘M[?] 3720’ at the bottom of the recto presumably represents the seller’s reference mark.

The leaf measures circa 142 mm × 61 mm, from crease to the more-or-less vertical cut edge. The text block of the surviving column measures circa 115 mm × 50 mm.

On each side, the leaf retains almost all of a single column of 23 narrow lines of text, parts of its upper and lower margins, and most of the inner margin. The edge of that margin extends to the ragged parts of the former stitching line, with bits of the inner margin of its former conjoint leaf or stub.

That the leaf formerly carried double columns of text (columns ‘a’ and ‘b’) is manifested by the portions of running titles standing in the upper margin. The surviving columns represent column a on the recto and column b on the verso, with the loss of 2 full columns of text between them.

Contents

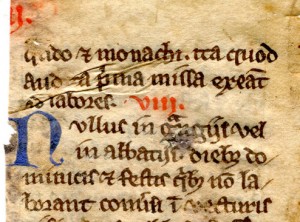

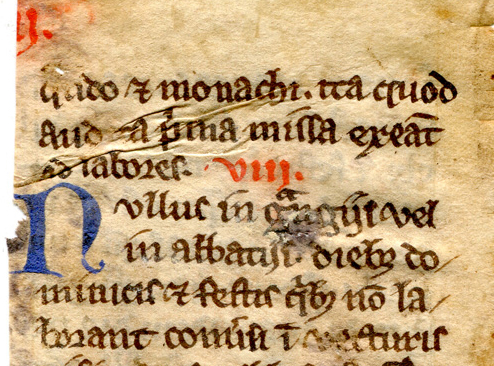

The remnant carries separate parts of the text of Distinctio or Section XIV (represented as [XII]II in its fragmentary running title), Chapter V, ‘De Conversis’. That is, the portions occur within the penultimate Distinctio of these Statutes.

In Fowler’s edition, this Chapter spans pages 502–510 in his ‘Part VI’ (Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, Volume X); the portions represented on the leaf appear on his pages 505–506.

- Column ra contains most of Chapter V.

It begins with faciant ordines suas and extends to ab idus septembri usque . . . - All of Chapter VI is missing.

- Column vb contains the text from the last bit of Chapter VII through most of Chapter IX.

It extends from quando et monachi, near the end of Chapter VII, to se sicut monachi, near the end of Chapter IX.

Noting in bold the missing phrases which directly precede and follow these portions, so as to signal the words by which the verso and recto respectively immediately preceding and following this leaf would have participated in the flow of the text (provided that the manuscript represented it similarly to the cited witness of Fowler’s edition), or the words which continued the flow on the missing columns of text on the leaf itself (column b on the recto and column a on the verso), it is possible to report the span of text represented upon the fragment. By these signs might the formerly adjacent portions of the manuscript and the leaf itself be readily identified, were they to survive.

Stranger things have happened. Such identifications guide reconstructions of the original sequence of dispersed leaves in various manuscripts, including some considered in our blog. For example, Otto Ege Manuscript 41 and Otto Ege Manuscript 61.

The citations here represent the presentation in the edition, rather than the spellings, capitalization, punctuation, abbreviations, or other variant approaches in “our” fragment.

Column ra corresponds to this portion of the edition (Fowler’s page 505) and its manuscript:

V. [ . . . sed ubicumque laboraverint,] /

faciant ordines suas [ni]si dies feriatus fuerit. Dominicis vero et festis diebus quibus non laborant, tam hueme quam æstate surgant ad vitilias quando et monachi. Porro qui de grangiis aut de via eadem die venierint, post quartum reponsorium eant dormitum si voluerint. Cæteri vero non exeant, sed totum servicium audiant, nisi eos aliqua recovaverit obenditia. Festis autem diebus quibus laborant in æstate, pulsato signo surgant ad cantica. Conversi de Abbatia cotidie eant ad complectorium ad ecclesiam. At conversi qui in grangiis fuerint a kalendis novembris usque ad cathedram sancti petri vigilent circa quartum partem noctis. et a cathedra sancti petri usque ad pascha et ab idus septembri usque

/ [ad Kalendis Novembris . . . ]

Column vb corresponds to this portion (Fowler’s page 506):

VII. . . . [In Abbatia vero] /

quando et Monachi; ita quod, audita prima issam exeant ad labores.

VIII. Nullus in grangiis vel in Abbatiis diebus Dominicis et festis quibus Conversi non laborant, in vecturis nisi pro victualibus deferendis, vel Ecclesiis construendis faciat laborare, nisi necessitas aliter exigerit.

IX. Quibuscumque diebus duæ Missæ canuntur, præcipuisque jejuniis, vel quando præsens defunctus fuerit Monachus, vel Novicius aut Conversus, et in sollempni commemoracione omnium fidelium, missarum intersint celebrationibus, nisi obedientia aliud præcipiat. In Ecclesia vero, in erectionibus et inclinationibus et cæteris observantiis, habeant se sicut monachi.

/ [Ad aquam vero benedictam . . . ]

The Rubrication

The running titles (now fragmentary) and the Section numbers (viii, ix) are written in red pigment. The Sections begin with inset and built-up 2-line initials (N for Nullus and Q for Quibuscumque) rendered alternately in blue and red pigment. The slender and mostly vertical tail of the Q descends in the intercolumn for 4 more lines. The roman numerals in both the running titles and the section numbers are sometimes flanked by dots, sometimes not.

The running titles (now fragmentary) and the Section numbers (viii, ix) are written in red pigment. The Sections begin with inset and built-up 2-line initials (N for Nullus and Q for Quibuscumque) rendered alternately in blue and red pigment. The slender and mostly vertical tail of the Q descends in the intercolumn for 4 more lines. The roman numerals in both the running titles and the section numbers are sometimes flanked by dots, sometimes not.

Lesser initials, written in Capitals in the same brown ink as the text, are highlighted with a wash, lines, or filler in red pigment. As an aid to legibility, they enhance the openings of the sections which run together within the lines, increasing the coverage of text-per-column. Only the Chapters merit openings on new lines (vb4 and 12), with inset, enlarged, and fully colored initials.

The bright red pigment is apparently vegetal in origin. It remains bright, rather than darkening or fading, as metallic red pigments tend to do over time and through exposure.

The Customary Titles

The fragment does not apply headings or titles to the Distinctiones. Fowler’s edition records them thus from his base manuscript (Lucet’s MS F):

V. De Conversis, quomodo surgant ad Vigilias

VI. De festis quibus non laborant Conversis

VII. De festis transpositis, quomodo fiant

VIII. De non laborando in vecturis festivis diebus

IX. De Missis quibus intersint conversi

Lucet’s edition of the 1257 Codification records the titles similarly on pages 340–340, with a few differences. This edition provides them with Arabic Numbers instead (5–9), and selects 2 readings different from Fowler’s choice. It has Conversi instead of Conversis at the end of Number VI/6, and relegates the phrase quomodo fiant of Fowler’s Number VII [or 7] to the textual apparatus at the foot of the page, where that reading or variant is reported as being attested in most witnesses: MSS F [=Fowler’s], Fd [Frauenfeld], H [Harley], L [Laon] , Pa [Pavia], S [Stams].

In these titles, the wording and the numbering sequence (minus 1 = 4–8) differs somewhat from the forms reported in parallel for the 1220 Codification upon Lucet’s same pages. Namely:

4. Quomodo Conversi surgant ad Vigilias

8. De Missis quibus intersunt Conversi

The point of these distinctions regarding the Distinctiones is that the New Fragment, even without having Distinction Titles, by means of its Section Numbering VIII and IX, aligns its record of the updated Cistercian Statutes with the 1257 Codification, not the earlier one of 1220, with which its text — according to Lucet’s edition of both these Codifications in tandem — also substantially agrees.

A useful distinction, don’t you agree, for the purposes of assessing the probable date of the fragment? And so, apparently it must have for its origin a terminus post quem (“boundary later than”) of 1257, when that version of the Codification was settled into place.

*****

We thank the owner of the leaf for permission to research and reproduce it.

Do you know of other leaves from the same manuscript? Please let us know.

*****

Next Stop: More Resources, of Course. Amazing what can happen when scholars and students meet the original sources. Expertise to the Rescue. Maybe that should be our new hashtag. Watch for it: #ExpertiseToTheRescue. It could start, or promote, a trend.

Check out the Contents List for our blog: Manuscript Studies.

Would you like to contribute as a Guest Blogger? Suggestions? Please leave a Comment here or Contact Us.

*****

Found this on MSN and I’m happy I did. Well written article.

Superb brief which post helped me a lot. Say thank you We seeking your information?–.

facebook