A Leaf from the Office of the Dead

March 15, 2016 in Manuscript Studies, Photographic Exhibition

A Part of the Office of the Dead

A Part of the Office of the Dead

from a 15th-century Book of Hours

made in Flanders

(perhaps at Bruges or Antwerp)

circa 1470

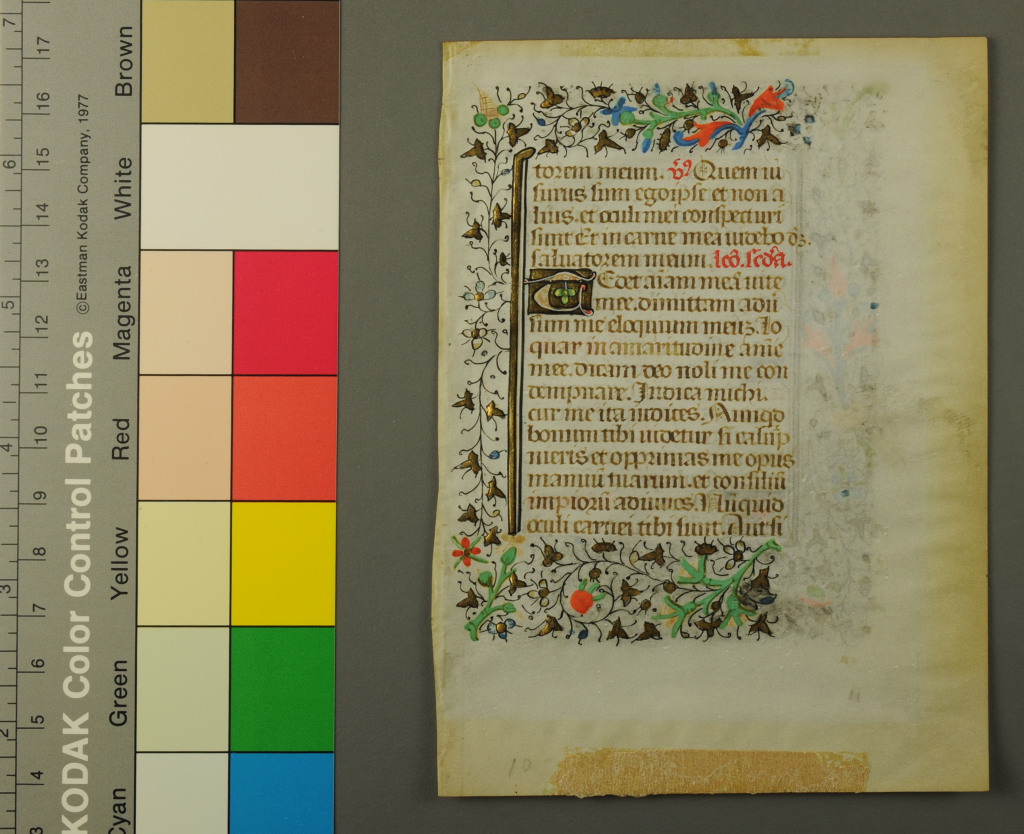

A single leaf, trimmed down in spoliation

to produce a decorated tidbit on its own

Circa 135 mm × 100 mm

< written area circa 66 × 50 mm >

Single column of 17 lines

Budny Handlist 12

Our series of posts by Mildred Budny on Manuscript Studies continues with a somber view of a detached leaf from the Office of the Dead in a gracefully decorated Book of Hours from Flanders. With this post, given the subject of the manuscript text, we also reflect wistfully on the passing of some friends, colleagues, and others dear to us. The occasion prompts us to offer a personal recollection of Jennifer O’Reilly (1943–2016).

Text and Layout

Manifestly the text on this detached leaf demonstrates that it forms part of the Office of the Dead. On its own, it is not exactly clear for which part of that Office this part of the text was intended to serve, mainly because there are no indications upon the leaf, and because the assigned practices for liturgical observance could vary considerably from place to place, custom to custom, and time to time.

Such is the nature of Books of Hours, a widely popular and personal genre of manuscripts or printed books in the late Middle Ages and Renaissance. At least we know which part of that set of texts, that is, the Office of the Dead, to which this leaf pertained in its original setting, although we cannot be certain of its specifically intended purpose, that is, which part of that particular Office. Discovery of other parts of the original book might reveal such features more precisely. Meanwhile, let us see what we can see.

The text — as here at Vespers — extends from within the

- Responsorum [. . . salva-] / -torem meum

to within

- Lectio tertia. Manus tue fecerunt me et plas– / [-mauerunt me . . . ].

The 17 lines of script in each column present the text mostly in long lines mostly justified evenly at its right-hand edge. Into the available areas at the ends of shorter lines there fit the rubricated titles or directions for the next text, each of which begins either in the same line (lines 1 on the recto and 15 on the verso = r1 and v15) or in the following line (lines v9 and 16). The compacted layout endows a stately presence to the text-block. The ornamental embellishments enhance that presence further.

There is a vertical banded gold bar at the left of each column, within the angular C-shaped open-sided frame formed of foliate and floral ornament, including pronounced monochrome or polychrome painted sprays. The frame and its decoration formed a template for both front and back of the leaf, in a form of approach in production which both economized on the effort of layout between one side and another, and ensured a consistency between those sides, or pages, of the given leaves. The elegant patterns and the expanses of gold endowed the pages with a splash of luxury. That the splashes extended to lesser pages in the text, such as this leaf set within, rather than opening, a set text (such as, say, the opening for Vespers or some other occasion within the Office, let alone the Office itself) may denote a level of expectant grandeur for the book as a whole.

The script corresponds to the style of Gothic rotunda (broadly or roughly described here). The script appears to indicate a Southern French origin or influence for the manuscript, which otherwise appears to have a Flemish origin. You see, the layout and ornamental decoration may point to a style practiced especially in Bruges, while the colours of the pigment, particularly the green, seem to correspond more with products of Antwerp.

The mixture of elements appears unusual to specialists of Flemish book-production whom I have consulted. The mixture may, say, indicate a confluence of traditions in the production of this particular representative. Perhaps the confluence could point to the origin and purposes of the volume. Further research, which might yield the recognition of other parts of the same manuscript, or products by the same hand(s), may advance knowledge of these questions. Presenting the leaf to wider notice here may well advance the process.

Sales Approach

A pencil inscription, partly hidden by masking tape, stands at the bottom of the recto. It begins ’10 —’ at bottom of the recto. Presumably it records a price followed by some further information about the leaf as an item for sale.

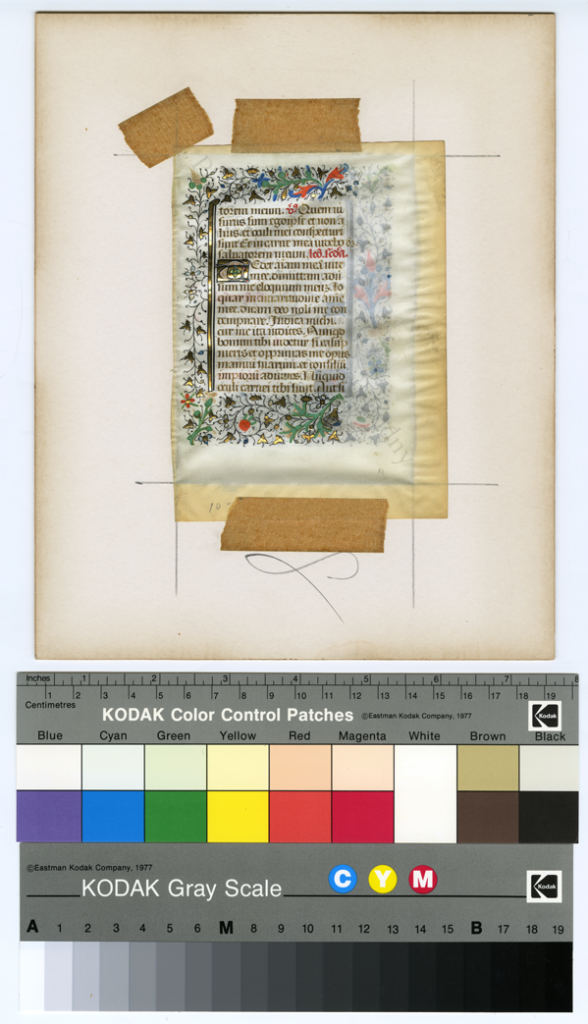

The conservative conservation undertaken for this leaf in 2008 chose, with consultation, to remove it from its archival-non-friendly mats. Contact with those mats over more than 50 years was shown to have stained and yellowed the adjacent edges of the leaf intended to be hidden from view in a Picture-Perfect approach, albeit obstructive from scholarly and archival perspectives.

I show here views before and after lifting the leaf from its acquired mounting. The former, perhaps suitable for a wedding present, presented the elements on the leaf as a double-sided ‘portrait’ of the leaf for display purposes. That the presentation, within a pair of acidic mats, plus non-archival masking tape applied willy-nilly to the edges, aimed to focus on the supposedly ‘worth-while’ viewing elements, ensured damage to the leaf is a sad element in the history of transmission of the material evidence across so many centuries.

Taking Sides, Both Sides Included, One Side At A Time

The recto of the leaf, revealed as soon as the leaf was (with the owner’s permission) removed from its former glassed frame, shows its fixatives with haphazard applications of archivally non-friendly masking tape, which to some extent have resisted all gentle efforts to remove. We decided to yield to the resistance, and leave that addition to adhere to the monument pending non-intrusive treatment.

-

The Recto still taped to its former mat

2. The Recto set free from its former mat

Transmission & Preservation

Its owner(s) acquired the leaf as a wedding gift, already mounted within a double-sided gilt wooden frame, in late 1959 from Josephine Edmonds Case (1933—2010). I have pursued this information, with some potentially useful insights.

With her first married name (before her second surname, by marriage to E. Robert Mason, Jr.), she produced a thesis on medieval manuscripts. It is: Josephine Case Schnurman, ‘Studies in the Medieval Book Trade from the Late Twelfth to the Middle of the Fourteenth Century with Special Reference to the Copying of Bibles’ (B. Litt. Thesis, Saint Hilda’s College, Oxford, 1960, with a copy here. This unpublished thesis, with valuable findings, continues to find citations in medieval manuscript studies, for example here and here.

The more-or-less coinciding dates of the wedding gift and the approaching submission of the thesis for the bachelor’s degree in literature at Oxford ensure that the choice of gift, in an extended family with extended connections, corresponded with the gifter’s interests and spheres of contacts, as well as with those of the recipients’, in combination. Her source for the gifted leaf is unknown, at least now, but some clues might reside under the masking tape following the numeral or price in an unspecified currency, rounded up to the full unit — say, in dollars or pounds sterling, either of which might pertain to the donor’s spheres of acquaintance.

The frame, with a pair of mats and glass panes, presented a back-to-back view of the leaf, cropped to hide the exterior of the margins and to cover the masking tape which affixed the recto to the second mat. That state of presentation for the leaf has now been superseded.

It was in this framed form that I first encountered the leaf. With permission, I removed leaf from the frame and its mat in 2008. The process revealed that, over time, the non-archival mats had stained and yellowed the covered edges of the leaf. Some of the masking tape was easily removed from the leaf itself, while the more resilient portion of the tape was left to stand, and the rippling of the leaf was gently eased. The owner has retained the frame for another purpose. The full sight of the leaf, front and back, can now be revealed for inspection. Back-lighting, as here, shows more clearly the ways that the ornament of the foliate border used the same template, generally, for both front and back.

3. The Verso

*****

And Now, Some Reflections on the Subject

For a while this post has been waiting publication because I thought it important to await a proper occasion. To issue a post about the Office of the Dead could be appropriate on any day, and every day. But it seemed to me to be a subject more valuable, and personal, than that. This observation includes reverence for Deaths as such and Deaths as inexorable, at any times. I decided to ignore the implications of such a theme as a wedding present, however well and luxuriously intended. I intended to wait for a moment that held a personal homage.

A Memoir for Jennifer O’Reilly (1943–2016)

This moment has come, alas, with the delayed news of the death in early February of my colleague Jennifer O’Reilly. Some of her contributions to medieval studies are reported on her faculty page. Her sensitive contributions, in print, in lectures, and in conversations, about medieval manuscripts and other works of art remain an eloquent testimony to her dedicated reflections about materials from the past, their intentions, and their value for continued study. I have mentioned their value on other occasions, and the opportunities for continuing to do so may emerge.

Now I think about her as a person, the living being with an incomparable spirit and a clear, but not loud, treble voice. Clear eyes, focused expression, graceful bearing. Womanly. Intelligent. Responsive. Lovely.

Over the decades, we met at various conferences and on other occasions, in her University and other places. I remember, for example, a happy dinner in her company, with her husband and colleagues, at a conference at University College Cork in 1987, in a room with bright interior evening lights and scintillating conversation, in which Irish style of discourse reigned (of course) supreme.

At the Colloqium which I co-organized for the Research Group and the British Museum in 2002, one of my comments in my paper — to do with learning how to swim in the waters of postgraduate studies in

At the Colloqium which I co-organized for the Research Group and the British Museum in 2002, one of my comments in my paper — to do with learning how to swim in the waters of postgraduate studies in

England by being dropped in the deep end, a method for learning swimming by which, in real life, I had been taught from the age of four, and taught well — led her to introduce me to one of the students attending, her former student, who also had expert swimming skills. Jennifer’s tender, caring pride in her student continues to reverberate in my recollection. The resulting conversation between the three of us soared, or, should I say, swam easily, freely. Sometimes the ways that we learn about our friends and colleagues may arise from offhand or spontaneous occurrences. Over time, they may re-emerge in poignant ways that allow the recollection to shimmer, with a newly acquired wistfulness.

At present, I focus somberly on the vivid memory of her heartfelt commiserations for an earlier loss, as we stood together in a corridor between sessions at one of the Annual International Congresses on Medieval Studies. It was 2012, when the Research Group was active as usual and she was one of the special Speakers, and so she traveled to America for the occasion. (Although I was the first Director of the Center which invited her, they do not invite me to their events.) We had had no chance to arrange a meeting beforehand, so the encounter was impromptu.

It was in between sessions that she caught sight of me in passing, in a corridor below ground, illuminated by unnatural lighting. Seeing me from a distance, among the throng of participants moving firmly from one room or building to another, she called and waved gracefully to me. As we drew closer, she began to tell, partly fumbling for the words in her wish to focus, at the unexpected chance, to talk about something which she had kept awaiting with intention building. It was her delayed response, delayed from reticence, to my brief news in a Winter Solstice card — by now this was May — about a death, about which I could scarcely speak, but the hints in the card were clear enough. It is a deep, private loss, still, and so its nature, apart from the strong sense of loss, does not enter this story now.

The point is that Jennifer took care, in that fresh moment, opportune in its own way, as soon as she saw me, to tell her response in person. As she said, with shining eyes beginning to brim with tears, she had not known how to write in response, but, here and now, was the chance to tell. And so there, in that enlightened corridor, setting aside the sense of time passing to consider together time passed, alas, we talked, and embraced, and wept, and exchanged commiserations, because she, too, had experienced a comparable loss of a beloved companion, about which words are not necessarily readily conveyed in writing, even though, upon hearing the news, the feelings are readily accessible, if not quite wholly expressible. The tone of voice, the gestures, and the expressions of the eyes and countenance may convey more than the written words themselves, however eloquent they may be. So, perhaps, it ever was.

But there remains a power in the written words which find, on occasion, fitting ways to express the laments and to mark the occasion of remembering the Dead, even across generations and centuries. The New Leaf with part of the Office of the Dead from an as-yet-unidentified manuscript is not mine to give, although for several years it was in my safe-keeping on loan, for the purpose of photography, conservation, and study. (Sometimes, but not in these cases, the owners of materials which I might photograph, conserve, and consult, often pro bono, give me a specimen or more in thanks. Another blogpost might tell about such thank-offerings, which I treasure, regardless of their material price.)

Now, in marking the passing of a scholar and friend whose keen awareness of the value of such rituals over time enlightened our understanding of a wondrous group of objects, manuscripts included, which have transmitted their traces to our gaze, I choose to send forth this account, illustrated by a sample of a decorous, gilded passage from an Office of the Dead for ritual observation and meditation. That it carries floral and foliate sprays aplenty, enriched with golden lights (as well as touched by some smears), and continuing to bloom despite the passage of time, may add to the sense of stately ceremony.

Jennifer’s sensitivity and eloquence taught valuable lessons about our human dimensions, and also about the subjects of study which she chose to illuminate with her graceful insights, poignantly conveyed. Thinking of her own words of comfort, I recognize their poignant pertinence to her own departure and their application to our sorrowful reflections now.

Jennifer’s sensitivity and eloquence taught valuable lessons about our human dimensions, and also about the subjects of study which she chose to illuminate with her graceful insights, poignantly conveyed. Thinking of her own words of comfort, I recognize their poignant pertinence to her own departure and their application to our sorrowful reflections now.

When I was a young child, I determined somberly, earnestly, to study the art and culture of Ancient Egypt, especially because of a perceived integration then, in some large measure, between daily life and the awareness of death. That the focus of my lifelong study changed over my early decades could be the subject of another reflection. For now, let it suffice to record that some lasting continuations of that preoccupation, applied to specific instances, have emerged over the years in the forms of funeral orations and memoirs for some beloved friends or family members. Sometimes I have the chance to stand before their graves and sing to them, as I sang to them in their lifetimes, but now my voice quavers in the sad song of the presence of absence.

Here stands another offering in that long, sad, and decorous tradition.

*****

We thank the owner for permission to study, conserve, and photograph the manuscript leaf, and to publish the findings here. We thank our Associate Gregory Clark and our Honorary Trustee James Marrow for expert advice about the decoration, date, and origin of the New Leaf.

If you recognize the style of the decoration or script, or know of other leaves from the dispersed manuscript, please let us know.

*****