Vellum Bifolium from Augustine’s “Homilies on John”

November 27, 2018 in International Congress on Medieval Studies, Manuscript Studies, Uncategorized

Recycled and Reclaimed

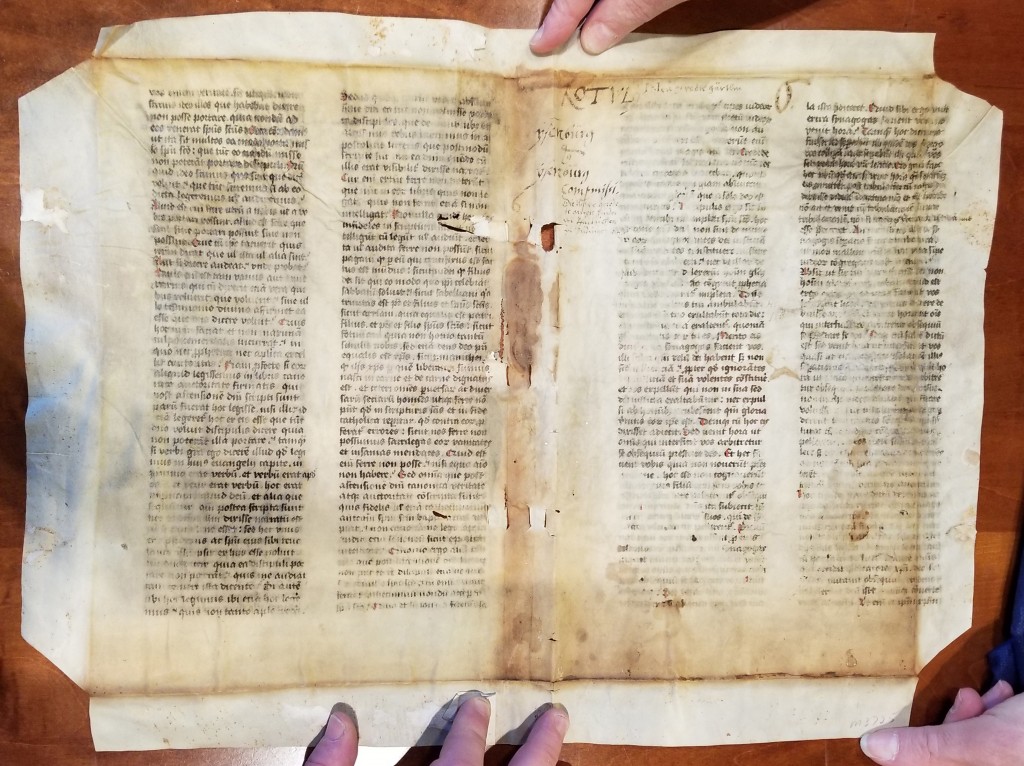

Large-Format Vellum Bifolium

from a Discarded Medieval Copy

of Saint Augustine’s Sermons

on the Gospel of Saint John

In Double Columns of 47 Lines

Measuring at most circa 384 mm high × 523 mm wide

< written area, or text block, circa 274 × 180 mm,

with columns circa 80 mm wide and intercolumn circa 20 mm >

Formerly Reused as the Cover for

An Account Book for A Garden at Ysenburg

For the Parish Church at Büdingen

Now in a Private Collection

[Published on 28 November 2018, with updates, continuing our series of Blogposts on Manuscript Studies, for which see the Contents List]

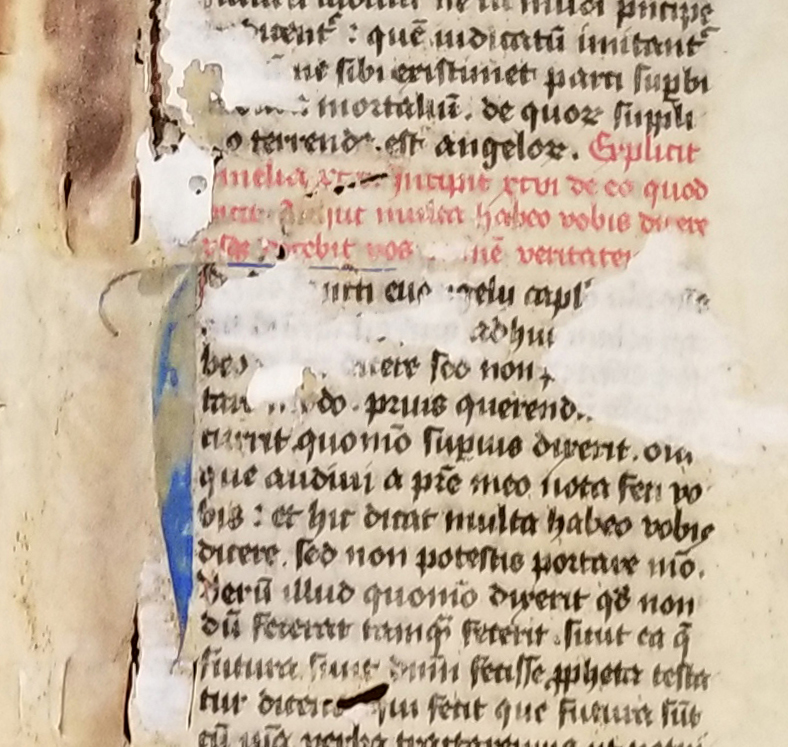

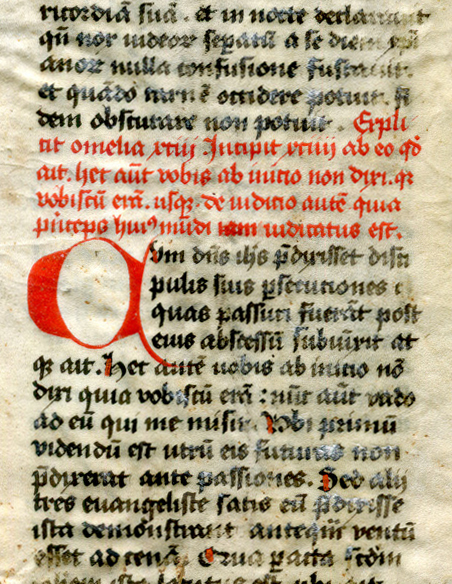

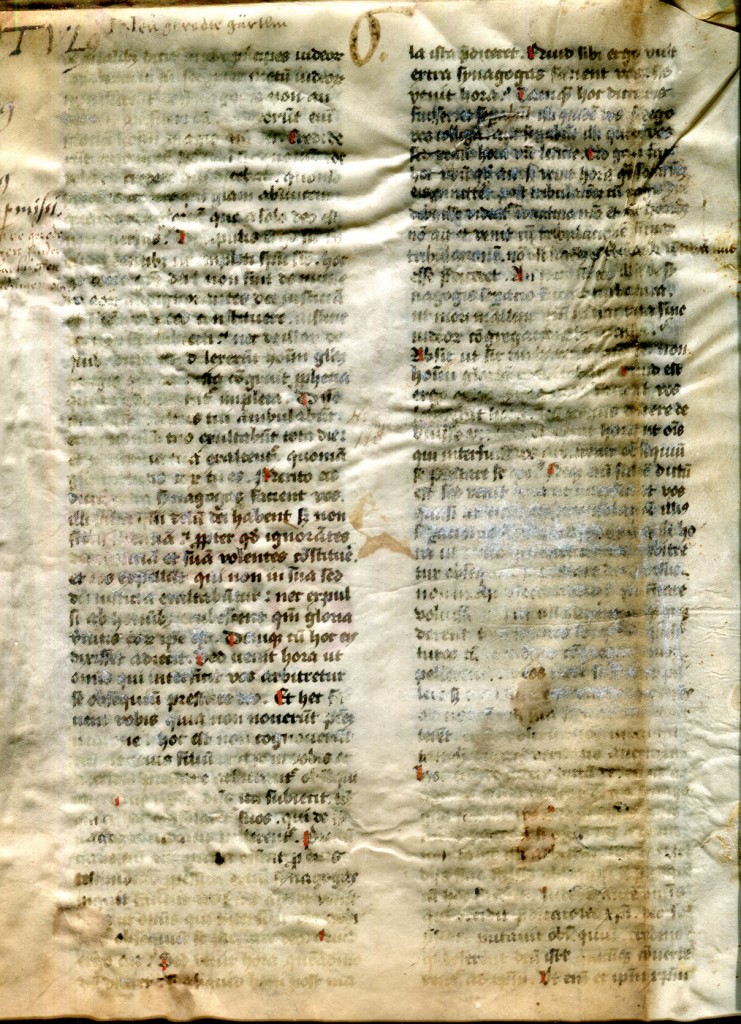

Augustine Homilies Bifolium Folio IIr detail with title and initial for Sermon XCVI. Private Collection, reproduced by permission. Photograph by Mildred Budny.

What

In this case, ‘it’ concerns a detached and reclaimed medieval manuscript fragment, in the form of a bifolium written on vellum. The fragment comprises a large piece of animal skin perfect for reusing, once the original religious text supposedly no longer mattered. Exigencies then claiming attention on site — wherever that site owning that volume would have been and whatever conditions prevailed — permitted the dispersal and reclamation of parts of the manuscript for altogether new purposes.

Long story short. The reused state left some traces upon the original artefact, comprising fold-lines, stains, wear-and-tear, added inscriptions, and more. But another, subsequent, stage of reclamation and reuse — in the pursuit of sales from old bits of written materials of whatever kind — has removed the reused wrapper from its former volume and led to its transfer, on its own, to a new owner, via commerce on the internet, but without the extra volume of post-medieval materials for which “Our” bifolium had served for some time as the outer cover or wrapper.

When

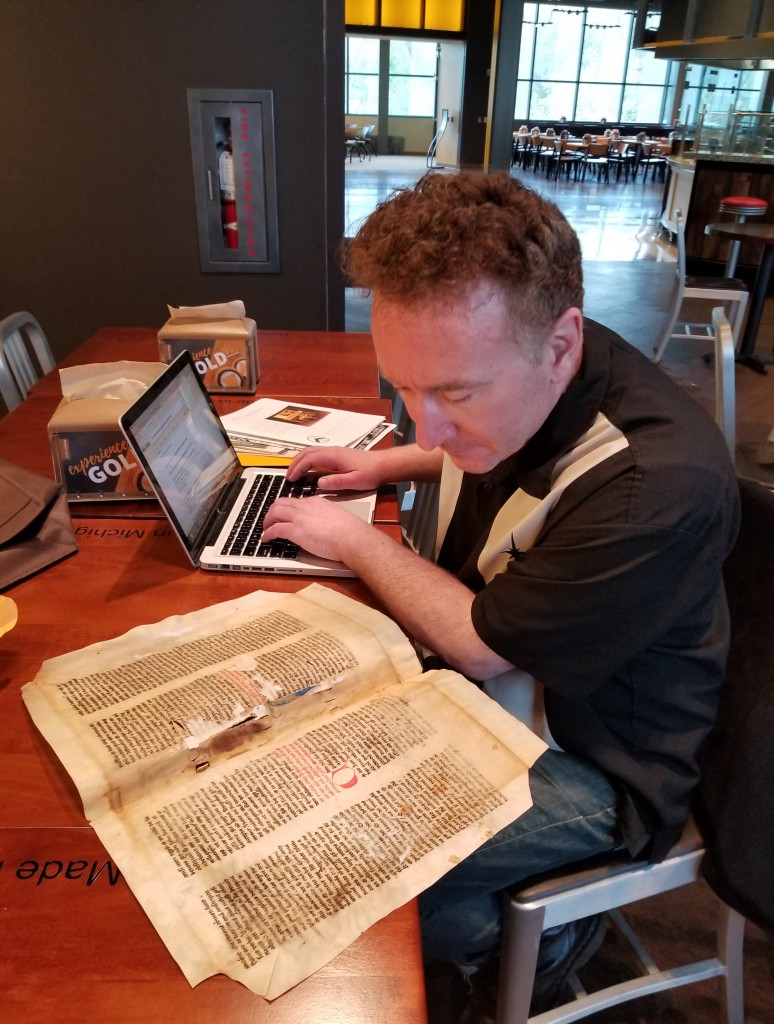

The Bifolium came into our view recently, with the occasion for examining some original written materials at an informal session arranged by the Research Group on Manuscript Evidence, gathering collectors, scholars, teachers, and students. About the occasion, see our Report.

“Having a Look”. Manuscript Consultation Session, By Appointment, at the 2018 Congress. Photography by Mildred Budny, organizer extraordinare.

Two Sides to Every Story

The Bifolium has an outside and an inside, according with the 2 sides of its original animal skin and the folding of the skin into a pair of leaves to carry the text laid out in double columns, each of 47 lines. The marks of damage over some time from the reuse as a binding cover or wrapper make manifest which side was outermost in that reuse. The identifiable original text and its sequence, as attested in other extant copies and in editions of the text, demonstrate that the outside of the wrapper and the outside of the bifolium in its original orientation in its manuscript placed the same side of the skin outermost.

Accordingly, for convenience, here we identify the first leaf of the bifolium, textually speaking, as “Folio I” and the second leaf as “Folio II”, with the recognition that originally there must have stood other leaves of the text in between them. We cite the pair of columns per page as columns a and b respectively, proceeding from left to right.

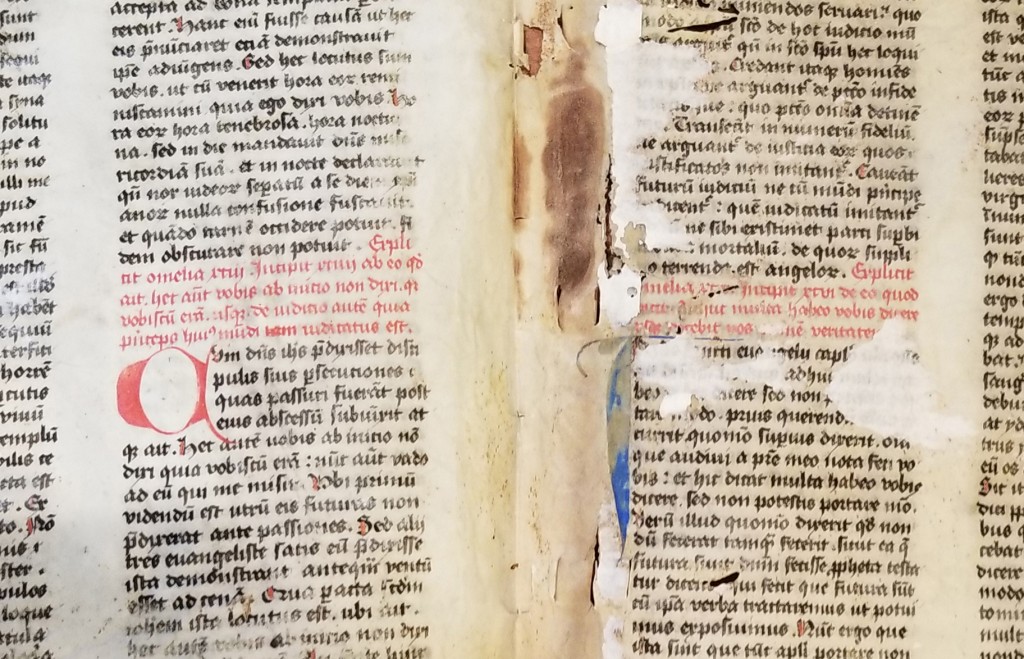

Outside of the Bifolium: Folios II verso / I recto

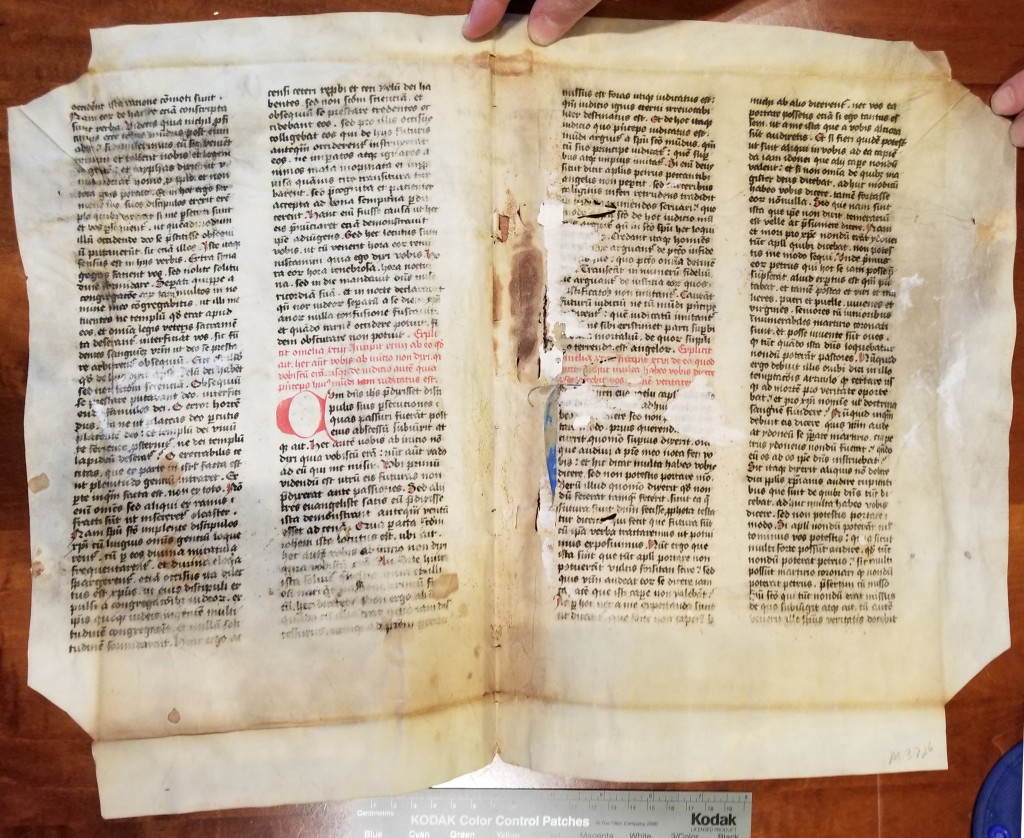

Inside of the Bifolium: Folios I verso / II recto

The Original Text

Despite some abrasion and wear in the reuse, along with a few adhering remnants of bright white paper from the former pastedowns, the original text on the bifolium is almost entirely decipherable. It is an advantage that the original script is precisely written, with distinctly differentiated letter-forms and only a few abbreviations, in the interests of efficient legibility.

So what is the text?

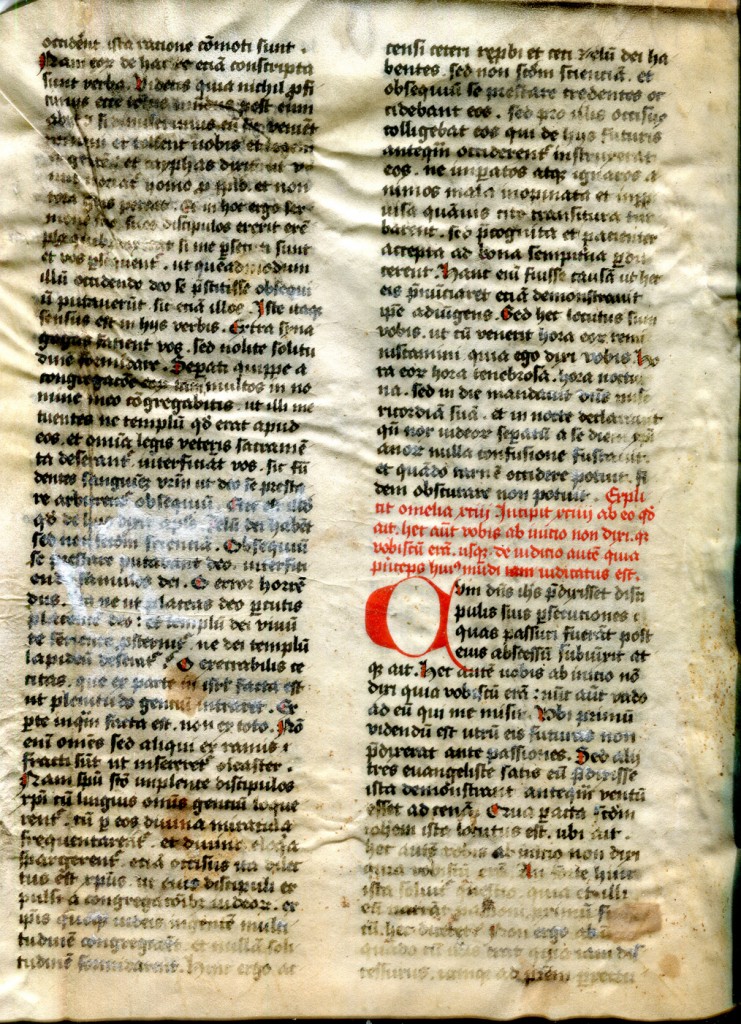

Let us take the “easy” or — anyway “easier” — route, which focuses first upon the rubricated titles, inscribed in bright red pigment (probably made of vegetal rather than metallic materials), ending one section or chapter of text and leading to the next.

The 2 titles on “Our” bifolium stand on only one side of the bifolium, but on two (non-consecutive) pages, as its Folio Iv column b and Folio IIr column a (= “Folios Ivb and IIra”). Namely on the inside of the bifolium. Here:

Augustine Homilies Bifolium Folios I verso column b and II recto column a: Homily titles and Opening Initials. Private collection, reproduced by permission. Photography by Mildred Budny.

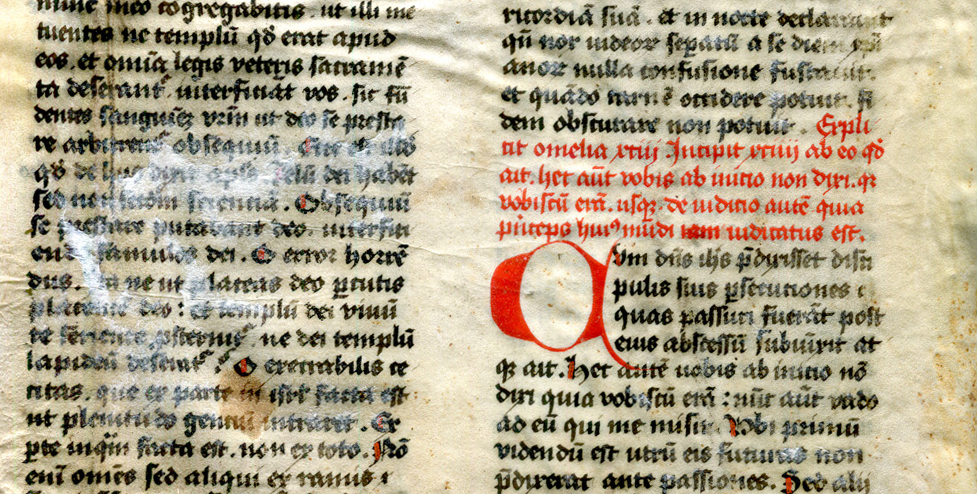

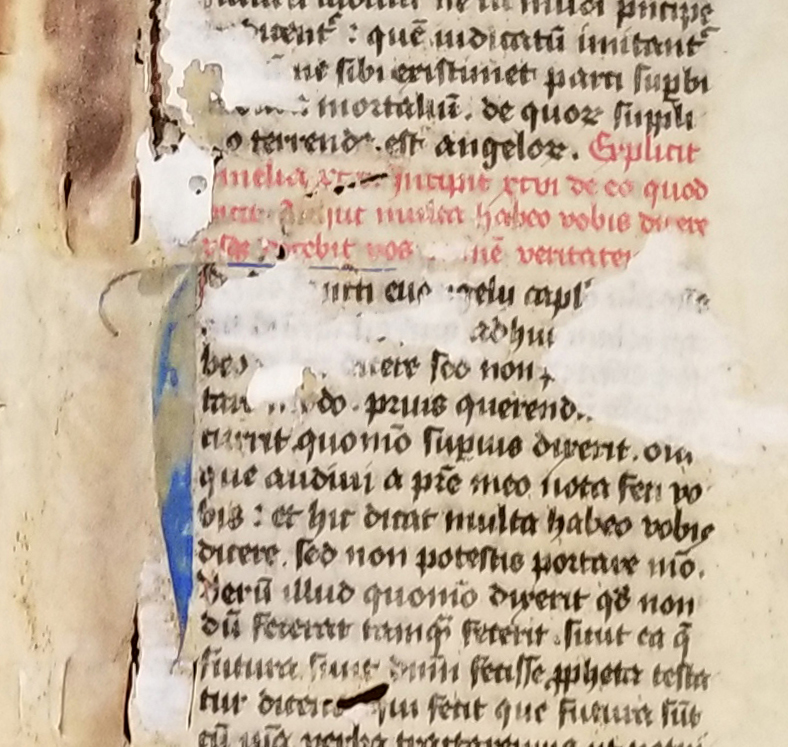

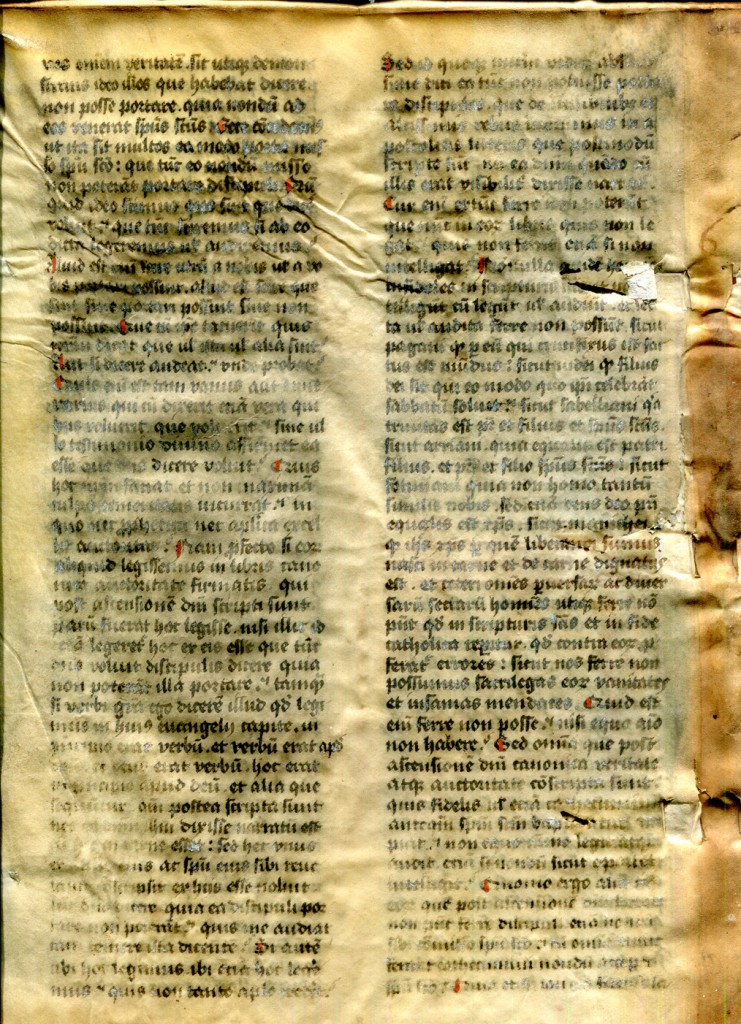

These 2 sets of titles extend for 5 and 4 lines respectively. In each case the title is followed by an enlarged initial which opens the text of the Homily in question: C in red for Cum and I in blue for In. Their opening titles declare these texts to represent Homilies XCIV and XCVI respectively, preceded — as the concluding titles designate — by Homilies XVIII and XVV respectively.

So: portions of Homilies XCIII–XVIV stand on one leaf of the bifolium, and portions of Homilies XCV–XCVI on the other.

On Folio Ivb, the prominent initial C (for Cum) appears in red pigment inset within 4 lines of the text. In contrast, on Folio IIra, the initial I (for In) stands alongside the column of text, descends for 13 lines of text, and appears in bright blue pigment. The quality of the blue pigment (probably expensive) and the attention to enlivening visual embellishment elevates this manuscript into a stature of careful, formal layout and presentation designed for clarity of reading.

A Copy Intended for Reading Aloud?

Such signs, including the imposing format of the text, might indicate an original manuscript with intentions for lection not necessarily only private. Another blogpost describes that process and such signs concerning a large-format late-medieval Lectern Bible manuscript: A New Leaf from ‘Otto Ege Manuscript 14’.

That “Our” Homily fragment carries no manifest marks for lection nor annotations of any kind appears to signal that any such intentions — if pertinent at all — received no such use in practice. In other words, the text on the bifolium looks like a rather clean, mayhap neglected copy. Perhaps no wonder it was destined for the scrap heap?

Whose Composition?

The rubricated titles on the bifolium make no mention of an author. Presumably the concise titles could easily have gotten away with that ‘omission’ because the original manuscript in full should, at its opening and perhaps also its conclusion, have presented his (or her) identity, as well as the overall title of the full set of texts. Thus a reader approaching the manuscript in its original state would have been able to have an orientation well established within the volume itself.

That was then. This is now.

Back To Front

Given the reduced set of material evidence, we readers and beholders now must confront the detached bifolium on its own, orphaned as it is, and must try (if we care) to perform some informed ‘reverse engineering’ or ‘DNA analysis’, shall we say, in order to determine the consanguinity with any and all leaves of its former manuscript, or to reconstruct the design and implementation (core text included) which led to its construction and accomplishment.

Fortunately, identification of the portions of text on the bifolium can be found among multiple resources, given the enormous prestige and proliferation of this author’s oeuvre — including this set of Homilies. Worth stating that not all those resources are equal in value, partly because some of the more up-to-date scholarly resources depend upon payment of subscription before access is permitted, and some freely available because copyright obligations are no longer valid present editions, translations, or evaluations long out-of-date and superseded by subsequent scholarship.

Aware that not all of us have access to those privileged, costly resources, I principally focus here, for ease of your access, on readily available links. For some other blogposts, where the details of the text called for such effort, I have made sure (and at cost, not freely available to me) to consult some resources that impact the assessment of the text, its specific readings, its potential impact on the transmission trajectory, and other factors with bearing upon the evaluation of the newly discovered fragment in question. For example: Another Witness to the Cistercian Statutes of 1257. But this current case might not (or not yet) call for such detailed treatment.

And so, now to “Our” Homily Bifolium, its texts, and its author.

Whose Text?

Identifying the text reveals its structure and its continuity — as well as its gaps, which occur before, in between, and following the pair of leaves in the bifolium. Customarily, in our blogposts (see their Contents List), we present the conclusions all in their reconstructed textual order, but, this time, we choose to show the identifications in the sequence as we found them, starting with the rubricated titles, ever useful as guides for locating their relevant texts.

The First Verso = Folio Iv and Its Title

Starting with the prominent cues, as in the title concluding one text and opening the next, plus the enlarged initial, it is relatively easy (given, for example, resources available on the internet, whether freely or by subscription) to identify the text on this page.

Explicit omelia xciij. Incipit xciiii ab eo quod ait. hec autem vobis ab initio non dixi. hec vobis secundum enim. usque. de iudicio autem. quia princeps huius mundi iam iudicatus est.

“[Here] ends Homily XCIII. [Here] begins [Homily] XCIV, from which it says: ‘Haec autem vobis ab initio non dixi, qui vobiscum eram’ [= John 16:5] up to ‘de iudicio autem quia principes huius mundi [+ iam] iudicatus est.’ [ = John 16:11].”

Augustine Homilies on John, Tractatus 93>94, Title. Bifolium, Folio Iv. Private Collection, Reproduced by Permission.

Augustine of Hippo and John the Evangelist

The text on each folio pertains to a consecutive pair of Patristic Sermons, or Homilies, devoted to the Gospel of John the Evangelist by Saint Augustine of Hippo (354–430 CE).

This extraordinarily prolific and influential author has already figured in our blogposts reporting newly discovered and recovered manuscript fragments (see our Manuscript Studies Blog Contents List).

Fictive Portrait of Saint Augustine of Hippo as a Author before his Text(s). He holds a Scroll in One Hand and Gestures before a Page of Text Placed upon a Lectern Beside Him. Fresco, 6th Century CE, Rome, Lateran. Image in the public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Augustine’s 97 Homilies on the Gospel of John, with portions of Homilies 93–96.

- English translations for the full series include some that are freely available online, as here:

Lectures or Tractates On The Gospel According to St. John - via New Advent: Sermons on the New Testament

- Lectures or Tractates on The Gospel According to St. John (in 671 pages)

1. Editions in Latin (of varying quality)

Some Latin editions of this work are freely available; others by payment or subscription. Some editions appear in the company of other works by, and presumed to be by, Augustine.

- Augustinus, In Iohannis evangelium tractatus CXXIV, edited by Radobodus Willems. Corpus Christianorum Series Latina, 36 (Turnhout, 1954; 2nd edition, 1990), described here.

- Augustine’s writings as a whole: Patrologia Latina, Series Prima: Volumes 32–47

-

-

- via Patristica.Net

- and by subscription, via Patrologia Latina Database

-

2. Translations into Vernaculars (ditto)

English translations for the full series of Augustine’s Homilies on John include some freely available online, as here:

The Text on “Our” Fragment

Each folio carries the end of one Homily and the beginning of the next. The identifiable text establishes which folio came first in the textual sequence and, moreover, makes it manifest that some leaves, now lost (or lost track of), formerly stood between the leaves of this bifolium.

The extant span embraces these portions.

Folio Ir – v: The end of Homily XCIII and the beginning of Homily XCIV

- Tractatus 93, commenting on John 16:1–4

The span on the leaf:

Tractatus 93:2 (/ . . . [de?] alibus [sic] dicitur multi principes iudaeorum) – 93:4 (fidem non potuit),

beginning mid-phrase and completing the Homily - Tractatus 94, commenting on John 16:5–7

The span on the leaf:

Tractatus 94:1 (Cum Dominus . . . perrectu-[/rus haec dixit . . . ],

opening the Homily and breaking off mid-word within its first Section or Chapt

[Gap between XCIV:1 (-rus haec dixit) and XCV:4 (missus est foras)]

However, the text on the 2 leaves of the bifolium is not continuous, so that some leaves must formerly have intervened between them.

Folio II r–v: The end of Homily XCV and the beginning of Homily XCVI

- Tractatus 95 commenting on John 16:8–11

The span on the leaf:

Tractatus 95:4 ([Nunc principes mundi huius] / missus est foras . . . de superborum supplicio terrenda est angelorum), completing the Homily in its concluding Section or Chapter - Tractatus 96 commenting on John 16:12–13

The span on the leaf:

Tractatus 96, 1 (In isto sancto Evangelii capitulo. . . . veritatis docebit), extending through its next Sections (with a continuation directly from Section 2 into Section 3 at the transition from recto to verso – Section 2 (quis non tanto apostolo crederet) / Section 3 (Sed id quoque) and continuing directly onto the verso (vos omnem veritatem sic ubique . . . ), carrying the Homily from its opening to near the end of Chapter 3

Augustine Homilies Bifolium Folio I verso column b: Rubricated Title concluding Homily XCIII and opening Homily XCIV, with its opening Initial I for ‘In’. Private collection, reproduced by permission. Photography by Mildred Budny.

Folio I verso both concludes the long text of Augustine’s Homily XCIII or Tractatus 93 and moves into the beginning of the long text of his Homily XCIV or Tractatus 94, with the transitional 5-line rubricated title positioned in column b23–27 and the opening text launched in column b28.

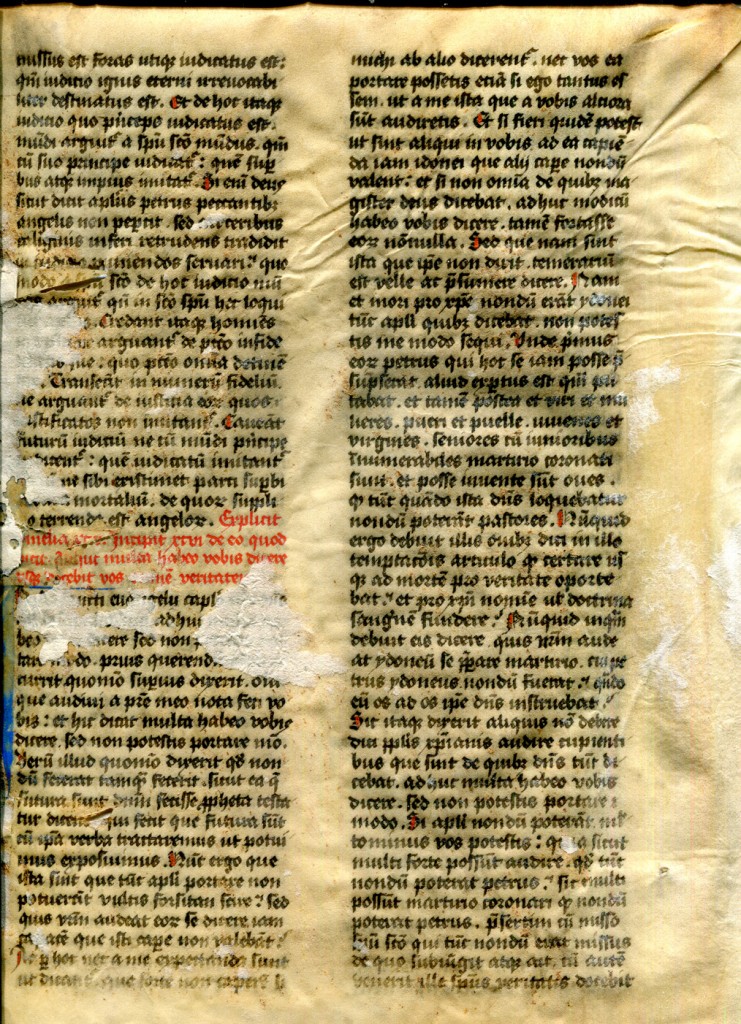

The Next Extant Recto: Folio II recto

Folio IIr concludes the long text of Augustine’s Homily XCV/95 with the words est angelorum, then turns to the title which ends this Homily and introduces the next, Homily XCVI/96, which begins: In isto sancti Evangelii capitolo . . .

With some damage, the title reads: Explicit [o]melia xcv. Incipit xcvi de eo quod [. . . ] habeo vos [om]nem veritate[m].

Thus it crisply specifies the span of the Gospel text under consideration, identifiable as John 16:12–13; see Ioannes 16 Biblia Sacra Vulgata (VULGATE).

12 Adhuc multa habeo vobis dicere, sed non potestis portare modo.

13 Cum autem venerit ille Spiritus veritatis, docebit vos omnem veritatem: non enim loquetur a semetipso, sed quaecumque audiet loquetur, et quae ventura sunt annuntiabit vobis.

Augustine Homilies Bifolium Folio IIr detail with title and initial for Sermon XCVI. Private Collection, reproduced by permission. Photograph by Mildred Budny.

The homily corresponds to Augustine’s Tractatus 96. With the text remaining within the edition’s Section or Chapter 1, the page concludes (column b) with the phrase Cum autem venerit ille spiritus veritatis docebit / vos omnem veritatem . . . . Quia etsi non eis [? fidelium sacra/[-menta produntur . . . ] near the end of Chapter or Section 3.

A translation appears, for example, freely here: Augustine’s Sermon 96 on the New Testament , translated by R.G. MacMullen, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, First Series, Volume 6 (Buffalo, New York, 1888), revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight.

The First Recto = Folio I recto > I verso

Working backward from the textual span on folio I verso to its recto, it is a straightforward process (once the text has been identified) to establish where the text begins.

Folio II verso

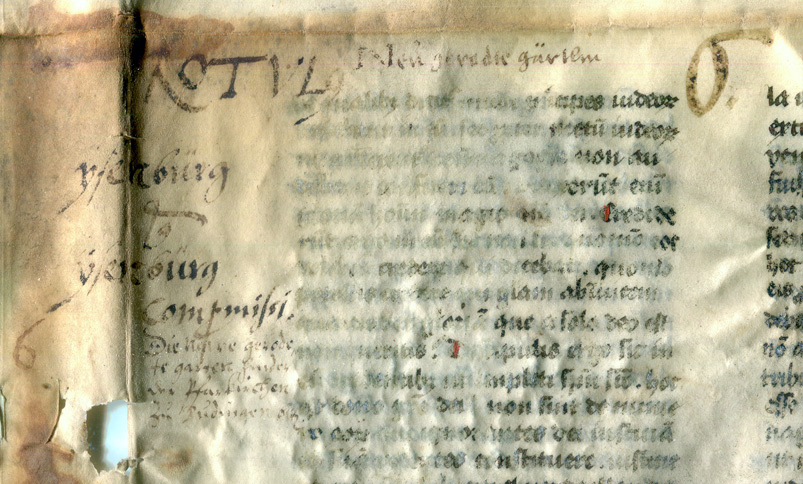

The Title and Docketing for the Reuse

The Parish Church at Büdingen

and Accounts for a Garden at Isenburg

Augustine Homilies Bifolium Folio I recto top with Docketing Inscription. Private Collection, reproduced by permission.

The docketing indicates that the reused remnant pertained to, and has come apparently from, Büdingen, in Hesse, Germany.

Where, For a Time

The docketing also mentions Isenburg (spelled both as Ysenbürg and Ÿsenbürg), “which makes sense as they were closely connected”. The collector observes:

My impression, after consulting what books I have, is that it’s Low Countries, mid-XV century. In other words, too late to be of textual importance. Others’ mileage may vary, but probably not by much. The docket inscriptions are not all that hard, as long as one can figure out the oddities of the hand.

Centered in the upper margin over column a on Folio Ir, the title, or running title, for that former volume specifies its contents. The inscription identifies the volume formerly covered by “our” medieval bifolium as ROTVL (“Account Book”), Number 6, entitled

ROTVL 6 Nen'[?] geradie gärtem

According to the title and description (or ‘Docketing’) which — according to its positioning in the intercolumn between the subsequent fold-lines — adorned its back, or spine, that former volume contained items concerning the records for a garden-plot in Isenburg (Ysenburg), which was owned, or worked on, or on behalf of, the parish-church at Büdingen. As said:

Ÿsenburg

Compromissi

Die na[.]re gerode

te garten finden

d[en?] Pfarkirchen

zu Büdingen [ . . . ]

Presumably the intermediate volume, for which “Our” Bifolium provided the covering wrapper, constituted an “Account-Book” (Rotul) of a garden plot in Isenburg, for which the plot was owned or worked by or on behalf of the parish-church at Büdingen. The present owner observes: “But I won’t guarantee that translation, as my transcription is shaky, and my German is rusty!”

The owner also provides further information about the provenance, with the observation that this bifolium comes from the same lot of material (dispersed in stages to different locations) as the astrology text examined in an earlier blogpost called Written in the Stars — “namely some of the dregs of a sale of material from the castle of Büdingen many decades ago”. (See also Castle of Buedingen.)

Schloss Büdingen seen from the Schlosspark. Photograph by Hadig 2004. Via Wikimedia Commons.

*****

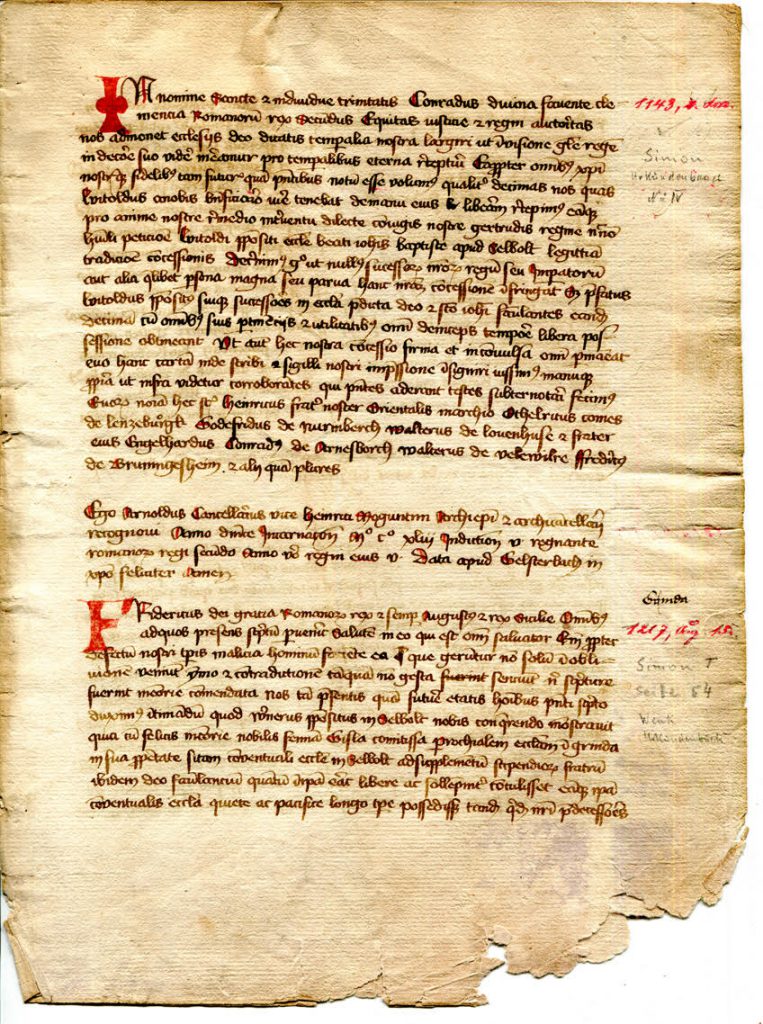

[Update in August 2020:

More recently, our research on a group of leaves in the same collection gave rise to our report on a set of fragments from a dismembered late-medieval Cartulary for the Abbey of Selbold in Hessen. Those fragments bear witness (eloquently, we have come to think, through our researches) to the interlinked history of documentary records — dispersed across time — from the spheres of influence of Isenburg and Budingen.

Among those spheres is the realm of Isenburg-Büdingen. Complicated? In a word, yes. For example:

Isenburg-Büdingen was a County of southern Hesse, Germany, located in Büdingen. It was originally a part of the County of Isenburg.

There were two different Counties of the same name. The first (1341–1511) was a partition of Isenburg-Cleberg, and was partitioned into Isenburg-Büdingen-Birstein and Isenburg-Ronneburg in 1511. The second (1628–1806) was a partition of Isenburg-Büdingen-Birstein. It was partitioned between itself, Isenburg-Meerholz and Isenburg-Wächtersbach in 1673, and was mediatised to Isenburg in 1806. In 1816 Isenburg was partitioned between the Grand Duchy of Hesse-Darmstadt and the Electorate of Hesse-Kassel.

A specimen from the fragmented Selbold Cartulary:

Private Collection, Selbold Cartulary Fragment, Folio 2 recto.

See Selbold Cartulary Fragments.

Now, intrigued by the interconnections of the dispersed materials which apparently came from that Castle, we examine sources for the medieval Parish Church at Büdingen, for which or by which was prepared the Account Book for the Garden, to be bound up within the reused Latin bifolium from Augustine’s Homilies on John in a manuscript perhaps otherwise unknown. Among the churches which serve and served the religious communities at Büdingen, the Parish Church associated with the Account Book is the edifice known as the Church of Saint Remigius (circa 437 – 533), Bishop of Reims. See the Saint Remigius Church at Büdingen and St.-Remigius-Kirche (Büdingen), for which the former is a translation into English from the latter in German. We learn that

In the 9th century, the church was replaced by a hall-like stone building. At the beginning of the 11th century, the western transept was built. About 1050, the two parts of the building were increased to the current height. The nave and the western transept were separated by a septum, which stands on mighty pillars. . . .

The church of Remigius was first mentioned in documents in May 1265, when Ludwig von Isenburg and his wife Heilwig, together with the parish church in Eckartshausen, transferred their revenues to the Cistercian nuns on the Hague near Lorbach .

The building was the Büdingen parish church until the end of the 15th century . The task as a city church took over in 1495 with the laying of the sacraments, the 1492 consecrated St. Mary’s Church . The St. Remigius Church was from then until now only used as a cemetery church.

Luther of Isenburg, who had been ordained for the clergy and appointed by his father Ludwig to the rector of the parish church of St. Remigius, led for several years with the help of his vicar the business of the parish, until he eventually resigned from his spiritual office in 1304 to take over the administration of his heritage. As a clergyman, Luther of Isenburg had shown particular interest for his Remigiuskirche, which can be proven by alterations and foundations.

Or:

Im 9. Jahrhundert wurde die Kirche durch einen saalartigen Steinbau ersetzt. Anfang des 11. Jahrhunderts entstand das westliche Querhaus. Etwa 1050 wurden die beiden Gebäudeteile zur jetzigen Höhe aufgestockt. Das Langhaus und das westliche Querhaus wurden durch eine Scheidewand getrennt, die auf mächtigen Säulen steht. . . .

Das Bauwerk war bis zum Ende des 15. Jahrhunderts die Büdinger Pfarrkirche. Die Aufgabe als Stadtkirche übernahm 1495 mit der Verlegung der Sakramente die 1492 geweihte Marienkirche. Die St.-Remigius-Kirche wurde ab dann und bis heute nur noch als Friedhofskirche genutzt.

Luther von Isenburg, der für den geistlichen Stand bestimmt gewesen und von seinem Vater Ludwig zum Rektor der Pfarrkirche St. Remigius ernannt worden war, führte mehrere Jahre hindurch mit Hilfe seines Vikars die Geschäfte der Pfarrei, bis er schließlich um 1304 von seinem geistlichen Amt zurücktrat, um die Verwaltung seines Erbes zu übernehmen. Als Geistlicher hatte Luther von Isenburg für seine Remigiuskirche besonderes Interesse gezeigt, was sich durch Umbauten und Stiftungen belegen lässt.

Note the connection with the Isenburg (and Büdingen) dynasty/dynasties. See Selbold Cartulary Fragments.

A recent view of the church in sunshine:

Saint Remigius Church at in Büdingen, Hessen. Photograph by Sven Teschke (2005) via Wikimedia Commons.

*****

We thank the owner of the bifolium for permission to reproduce and publish it.

More?

Do you recognize the script, scribe, or manuscript? Do you know of other leaves from the same book, by the same scribe, or from the same center of production?

We offer these images for further examination and, it may be, recognition.

‘Inside’ of the Reclaimed Homily Bifolium

Please let us know. You could leave Comments here, interact with us on Facebook, or Contact Us.

Watch for more discoveries in our blog. See its Contents List.

Contributions and Donations Welcome! Please join our our Contributions & Donations.

*****

Awesome discovery! This was really helpful. Thanks for sharing!

This is interesting yet helpful. Thanks for sharing this.