Italian Notarial Roll of 1305 from Cesena

July 10, 2016 in Documents in Question, Manuscript Studies, Photographic Exhibition

Scrollwork

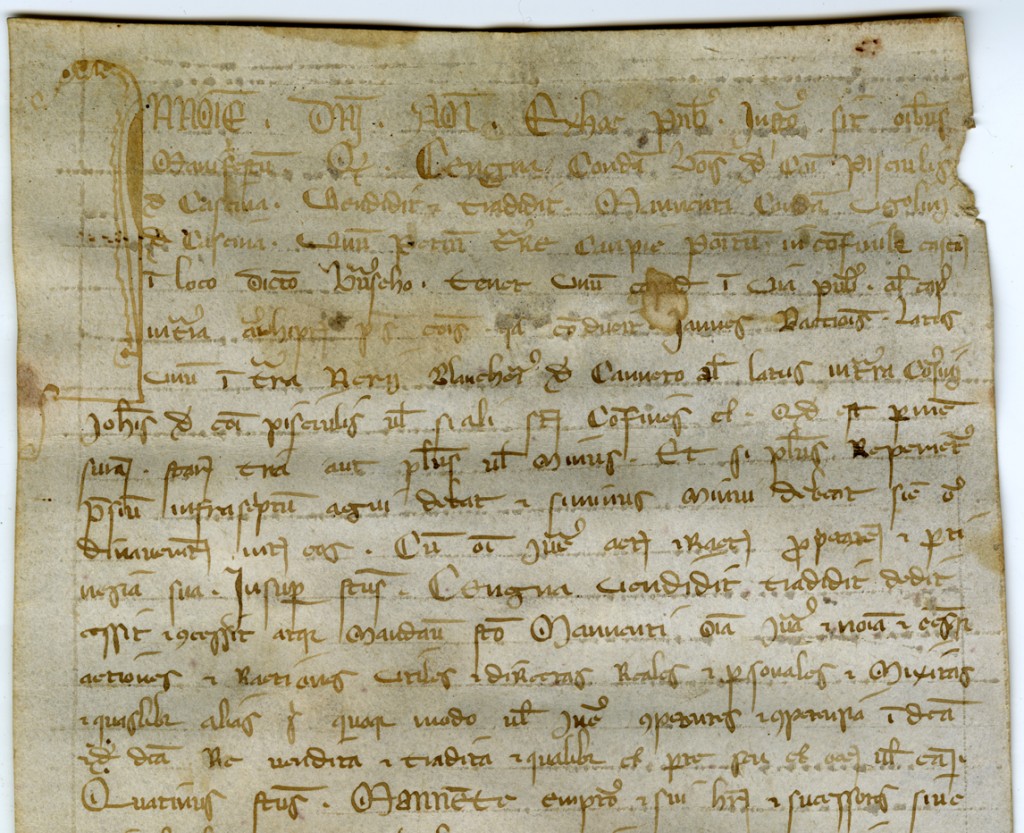

Notarial Document Roll of 1305

in Latin

with Docketing in Italian

Budny Handlist 20

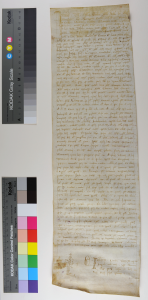

Mildred Budny continues our blog on Manuscript Studies with the publication of a Latin document recording one transaction (a sale of land) on a single sheet of vellum in roll form, issued by the notary Johannes in 1305 at C(a)esena in Emilio-Romano in Italy, and provided with a docketing inscription in Italian on the dorse. This document joins the cases from Preston in Suffolk, from Grenoble, and from somewhere presumably in France already brought to light in our series.

For a change in this blog, here we place a few bibliographical references at the end. They provide the fuller citations for sources mentioned along the way in concise form — as with ‘Roschach (1867)’ — as well as a few suggestions for further reading.

Data

Document as a Whole

Circa 477 × 147 mm

< written area circa 464 × 142 mm

including the notarial inscription

or circa 464 × 422 mm without it >

Single column of 64 lines overall

(4-line notarial subscription included)

written in light brown ink

in cursive documentary script (cursiva currens)

with notarial sign

On the front or ‘face’ of the roll, the text of the Latin document extends for 60 long lines, plus the notarial sign and signature in 4 shorter lines offset to the right.

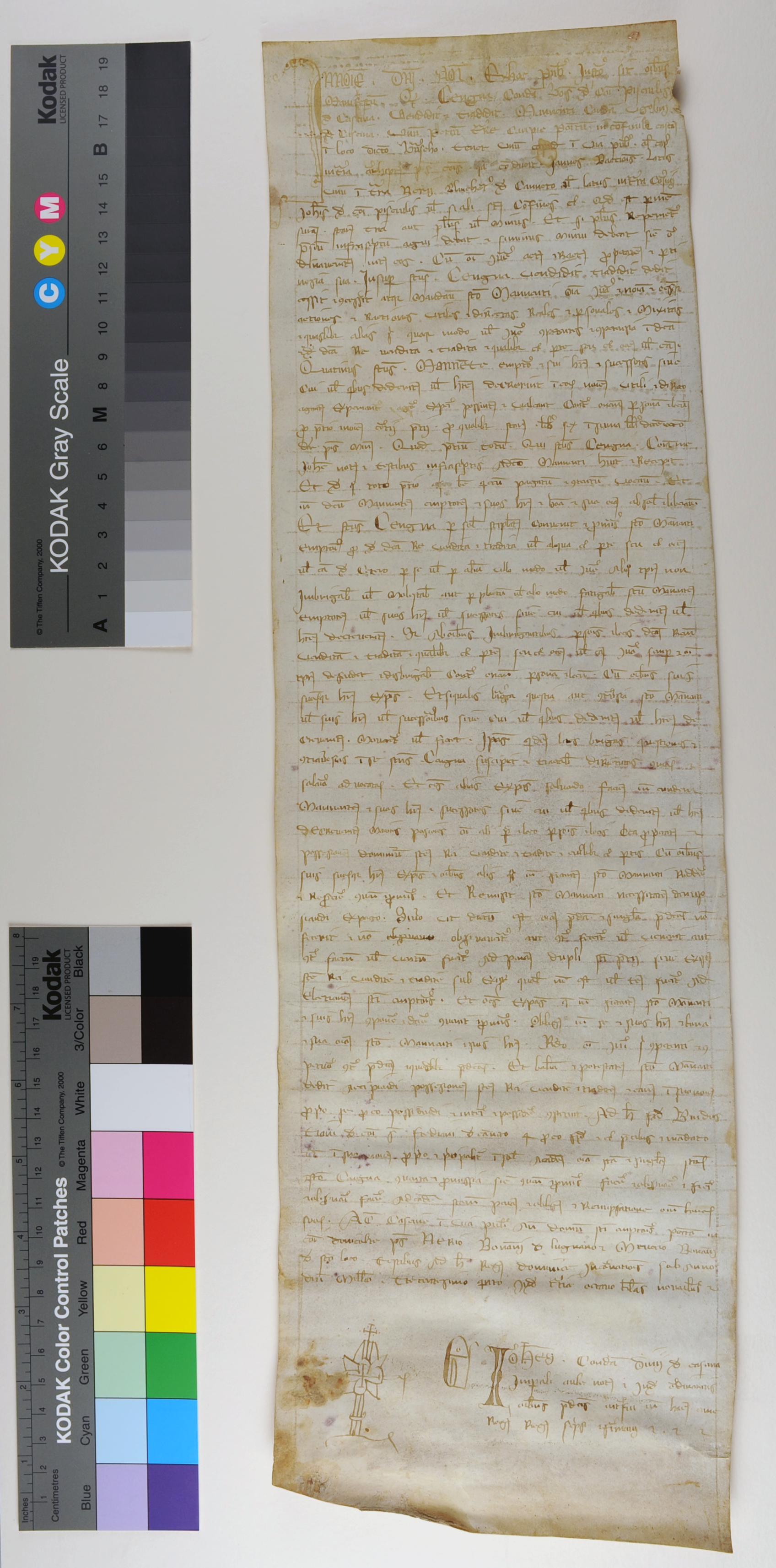

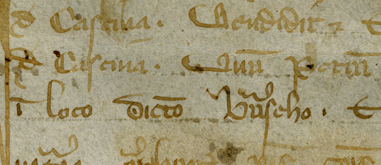

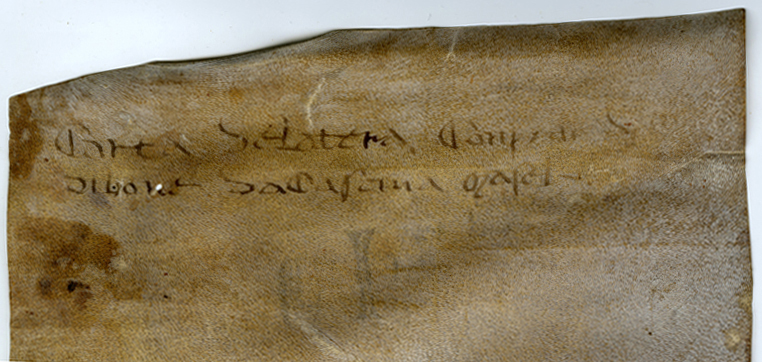

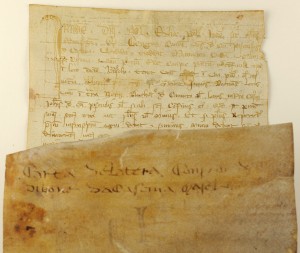

The back or ‘dorse’ carries 2 docketing inscriptions, at opposite ends. Each spans 2 lines. The medieval Italian inscription appears in brown ink. Added later, the numeric inscription appears in darker, thicker ink, noting the date in post-medieval form.

Front & Back

The document turns the whitish flesh side of the animal skin to its face and the yellowed hair side to its dorse. The hair side retains the distinct patterning of the follicles.

The inconsistently trimmed edges of the document produce a more-or-less straight edge for the left-hand side of the text, a sloping top, and uneven other edges, which taper outward to an extended tip at the bottom outer corner of the face. The downward slope of the bottom edge includes a ridge formation which corresponds to the contour of the skin as it took its shape upon the body of the animal. In keeping with the taper of the scroll, the lines of text expand in width from the top line downward.

The inconsistently trimmed edges of the document produce a more-or-less straight edge for the left-hand side of the text, a sloping top, and uneven other edges, which taper outward to an extended tip at the bottom outer corner of the face. The downward slope of the bottom edge includes a ridge formation which corresponds to the contour of the skin as it took its shape upon the body of the animal. In keeping with the taper of the scroll, the lines of text expand in width from the top line downward.

On the dorse, 2 short inscriptions of 2 lines each in ink at both the top and bottom, and by different hands, provide descriptions or labels for the contents of the document. Each entry stands close to the edge, with the top of its text turned to that edge. One provides a description of the contents; the other indicates the date of the document.

Thus these inscriptions stand upright in opposite directions, as their entry occurred when viewing the document respectively from the long (‘vertical’) end or the short (‘horizontal’) end. Or by rolling the document from one end or the other, whereby the inscription (whichever) could face outward conveniently on the rolled unit.

Roll On

Given the orientations of these inscriptions, one storage arrangement rolled the document inward from the top of the text, allowing the broader bottom of the roll to enclose the unit, whereas another rolled it inward from the bottom, requiring the narrower top to wrap around the fuller width of the inner scrollwork. The chewed edge along the ends of lines 1–3 of the text reveals the actions of rodent(s) apparently while the roll lay with the narrower end outward, bringing the inscribed date into view.

The orientations of the inscriptions demonstrate different approaches to motions in opening and closing the rolled document. The relative dates of these inscriptions encourage the reflection that the position of the earlier inscription represents a prior, perhaps original, intention for closure.

The Notary’s Location

The document was issued by a notary of one of the Imperial cities, according to its notary’s declaration of credentials ( . . . Imperiali aula notarii, that is, ‘of the imperial notarial hall’). It declares itself to be an official record effected at Casana: Actum Casane’ in ciuitate publice.

The location: Cesena (English version) or Cesena (Italian version) in the Emelia-Romagna region in north-east Italy.

Cesena stands alongside the Roman Via Emilia (completed in 187 BCE) connecting the towns of Rimini and Piacenza. The place was one of the strongholds built along this trunk road at every 20 kilometers – that is, the distance which a Roman soldier could walk in one day.

The Text

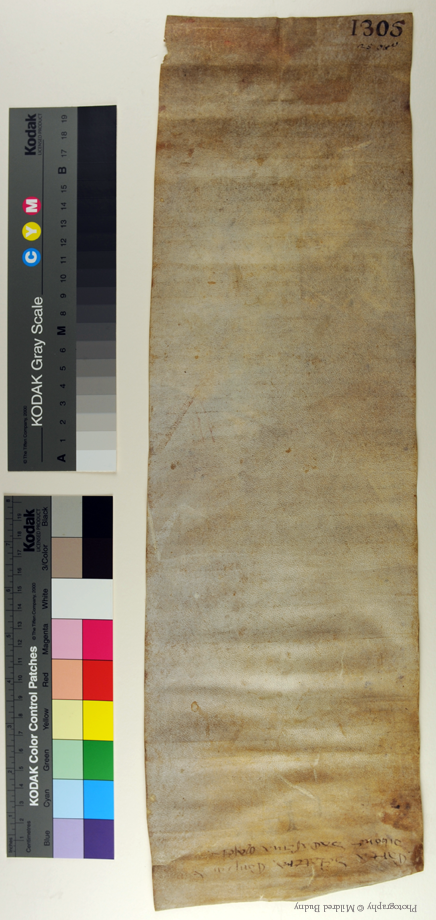

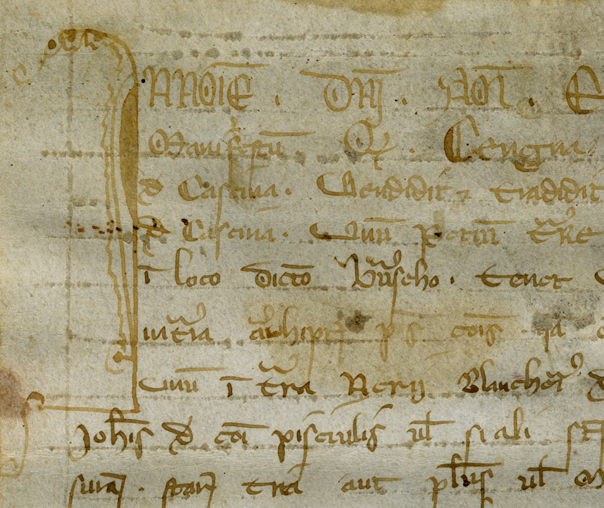

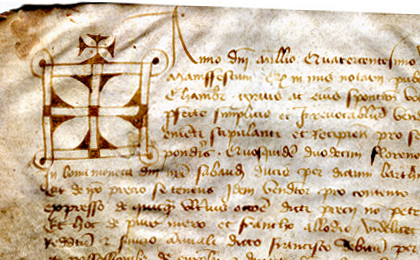

With a standard formula, the text begins In Nomine Domine Amen (“In the Name of God, Amen”). Next it declares its purpose: Ex hac publico Instrumento sit omnibus manifestum (“From within this public Deed may be it known to all”). Then it reports the transaction, in detail, followed by a detailed record of the place and date, the names of witnesses, and the notary’s sign and attestation.

Partly outlined and partly filled with the same brown ink as the next letters, the opening initial I stands 7 lines high, inset within the column of text and extending partway into the upper and inner margins. Its elongated shape resembles a debased version of an upright bird-like creature, shown in profile facing left, with a folded wing, arched neck, circular eye, and upward curled beak. This schematic creature seems a remote cousin of the stork-like bird standing upright, with folded wing and nibbling beak, at the top left of a more ornately and expertly decorated document of 3 December 1201 from Bari in Apulia; the document is reproduced as plate 29 in large format in Petrucci (1958), from Le pergamene del Duomo di Bari, I (1897), page 137, plate VIII.

The document solemnly records a single transaction. It concerns the sale of land by one Cengna candam Bos’ de Ca’ Pisciulis de Casina to a Manncuti candam Ugolinis de Casina. The Latin quondam (appearing on this document as condam in the case of these individuals or candam in the case of the notary) might mean “formerly”, “at one time”, “sometime”, “deceased”, or the like, depending upon context. Here it may stand either for a place of origin or for a “son of the late N”, with the word filius (“son”) to be understood. Whether by affiliation or blood-relation, Cegna pertained to one Bos’ from the Ca’ de Pisciulis, while Manncuti pertained to a (H)Ugo of Casina. If these specific individuals might be found in other records with clearer particulars concerning the relationships and locations, we could be in a better position to decide who is who, which is where, and what is signified in each case within the document.

Another time, we may address the contents of its text, its people, and its spaces. Among them, for example, are named the witnesses

- Nerio Bonanni of Lugnano in Umbria

- Meuaio Bonanni “of the same place” (lines 58–59).

The boundaries of the land, stated to be in loco dicto Bu’scho (“in the place called Bu[r?]scho” (line 5), refer to properties pertaining to these individuals, whose names are reported in the genitive, which we reproduce, abbreviations and all:

- Jannes Dactiais’

- Nerii Blanch[er?]ei’ de Canneto

- Iohannis de ca’ pisciulis (lines 7–8).

Candidates for this Nerio’s place-name or surname occur among various municipalities or parishes known now as Canneto — presumably, shall we say, the one known as Ronco Campo Canneto in Trecasali in Emilio-Romano, rather than those other (surviving) Canneto’s located in other parts of Italy. (Place-names and places by those names which have disappeared from the record should not be ruled out, pending further notice.)

The Ca’ Pisciulis (“The House[?] of the Little Fishes”) to which pertain the appelations both of this boundary-owning Iohannes and the vendor Cegna condam Bos’ de ca’ pisciulis de casina (. . . “of the House[?] of the Little Fishes of Casena”) awaits identification. Same for the “place called Bu’scho”. (Although Italian place-names are not, anyway yet, my speciality, my long study of English place-names, and other names, gives a healthy respect for the complexities of the evidence, in many realms.)

For now, we focus upon the artefact as such, in introducing it to wider study.

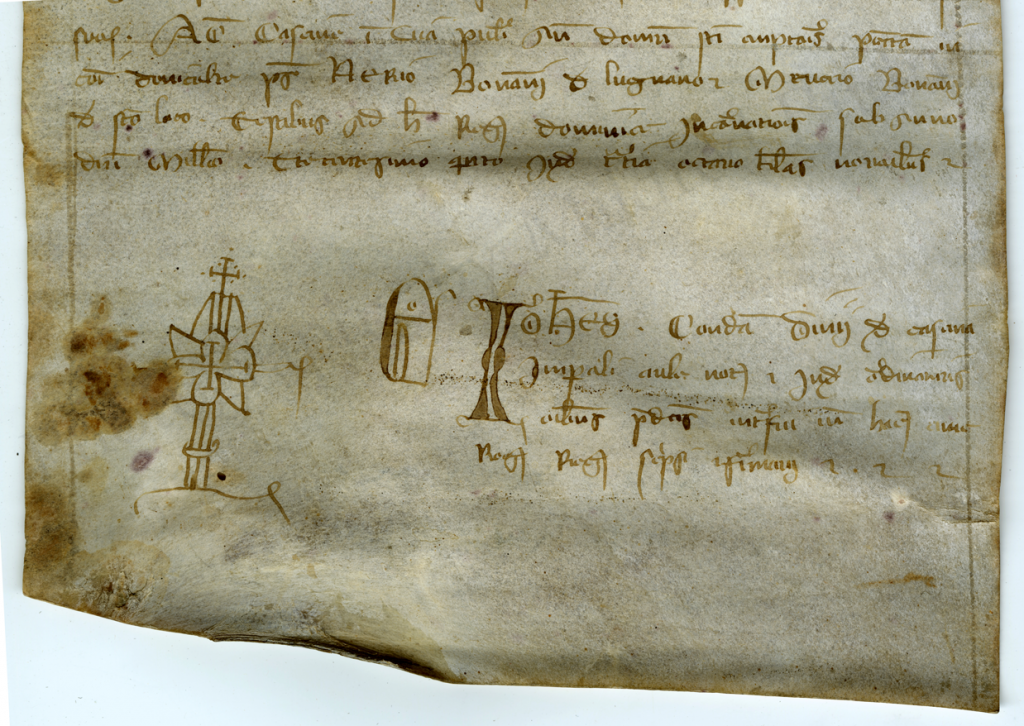

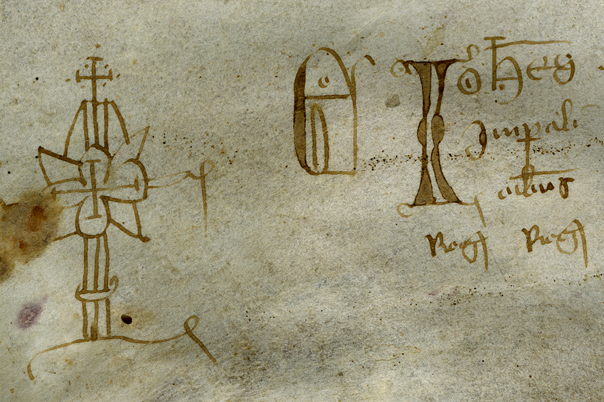

Notary’s Signum and Signature

Written in long lines in a rapid documentary script (cursiva currens) with plentiful abbreviations, the text of the document concludes with the statement that it was written at Casana and with the date: Sub anno domini millia [.] trecentisimo quinto indictione tertia octauo kalendas nou[?]ambri[?]s (‘In the thousand-three-hundred-fifth Year of the Lord, in the Third [papal] Indiction, the 8th of the Kalends of November[?]’). This dating clause in the Roman calendar converts to 25 October 1305 A.D.

There follows, at a distance and inset toward the left, the elaborate graphic signum tabellationis (‘sign of the tabellion [or notary]) of the imperial notary, and his attestation in the first person, declaring the authenticity of the copy. This portion opens with his name and office: Ego Ioh[ann]es conda[m] Dinii’ [=domini?] de casana imp[eri]ali auli notar[ius] et iud[ex] o[r]dinarius a[uctoritat]ibus p[re]d[i]c[t]is int[er]fui in hanc c. . . rog[ata] rogat[us] sc[r]ipsi [et] i[n]firmavi (‘I, Johannes, formerly of D… [perhaps pertaining to “the Lord”?] of Casana, notary of the imperial hall and regular judge, by the aforementioned authorities, . . . have written and confirmed.’).

Strange, perhaps, that the Tabellion Sign is tilted forward, exactly like the First Person Pronoun and the Scribe’s First Name, whereas the rest of the attestation, written in script similar to the text of the document, appears upright in relation to that text. The contrast in orientation implies that the scribe sat at one angle to the face of the scroll as he wrote both the text and most of the attestation, but at another angle as he entered his notarial sign, pronoun, and given name.

“Cross My Art”

This notary’s unique sign, as often among Western medieval notarial signs (Christian, that is), includes a cross. More than one, in fact.

Here (viewing it upright), a cross surmounts an embellished shaft — apparently the form of the letter I (the scribe’s initial) — which stands upon an undulating baseline. Extending in both directions, this baseline ends at the right with an upwards loop to a descending diagonal tail.

The cross ascending from the top of the I is flanked by dots. The segmented or balustered stem of the I presents an enlarged roseate foliate motif which encloses another cross. That cross ends in short perpendicular bars.

Among Notarial Signs of the medieval and early modern periods, some combine a surmounting cross with a cross or cross-shape within the central motif, portion, or panel. An example in a document dated 1437 from Chambèry in Savoie in France, and now in a private collection, has already appeared in one of our Galleries devoted to Latin Documents & Cartularies. Needless, perhaps, to say, but worthwhile to illustrate, the degrees of craftsmanship and skill in design varied from individual to individual.

Italian Notarial Signs of the Late 13th- and Early 14th-Centuries

A couple of similar Notarial Signs appear among a group of Signa tabellionatus of Florentine notaries, as registered in Florence in 1316 and reproduced in Plate 52 of Petrucci (1958). The plate displays an opening in Florence, Archivio di Stato, Arte dei Guidici e Notai, vol. 6, folios 8v–9r. There, the signs for the notaries Andreas and Bonaparte employ more-or-less upright, segmented columnar or pillar-like structures supporting expanded quadripartite or rosette elements. The sign for Andreas (folio 8v) stands on a more-or-less horizontal baseline which loops downward at the left and upward at the right. Surmounted by a cross, the sign for Bonaparte (folio 9r) includes a fat roseate element comprising a hexfoil. Moreover, from four of its cusps emerge pointed leaf-like motifs, while from the cusps at its mid-section extend pen-lines which form looped, downward-turned tails — like the sign of “our” Iohannes.

Whereas we cannot consider their I-shaped signs to have a clear formal link with the Florentine notarial names Andreas or Bonaparte, we may be entitled to regard that of the Cesenan Iohannes in such terms, at least in part or after the fact.

A similar sign among Petrucci‘s plates pertains to another Italian imperial notarial Iohannes, this time in a document of 24 January 1324 at Iglesias, Sardenia (Plate 53). He signed as Ego Iohannes filius condam Rustichelli Arharii imperiali auctoritate, with a notarial sign having a segmented shaft, donut-like circlets along its length (at mid-section and base), and a quatrefoil rosette (with dotted centers in the lobes) supporting a cross flanked by dots. The same notary’s attestation appears in a document of 9 May 1298 from Iglesias, with the same formulation, as edited in Fadda (2009), number 16 (at pages 166-168), but I have not seen the notarial sign in that case.

In sum, the elements of the individual signs followed certain types, with inevitable personal variations required by the genre.

The Alphabetic-and-Geometric Type of Notarial Sign

Among the several types of signets authentiques employed by medieval notaries, this sign (or signum) represents a combination of Alphabetic and Geometric shapes. In his study of the signs employed by notaries in Toulouse in France, Ernst Roschach (1867) grouped them into 5 types:

- Parlants (functioning as a sort of rebus)

- Héraldiques

- Mystiques

- Alphabétiques

- Géométriques.

However, these individual types might be more prevalent at one period than another, and they might overlap with one another, even within a given sign. (As here.)

I like this classification — to which more types and combined types might be added, according to the times, places, and habits adopted for the changing forms of individual, unique, signs in notarial practices from the medieval to modern periods — because it encourages the signs to reveal their ‘readings’ more directly. Or (Also?), it encourages and directs us to ‘read’ them and their component parts more clearly.

Among the several types, the Alphabetic form tends toward a signature as such, as we now know them. At the beginning (in about the second half of the 13th century, according to Roschach), only a single initial might serve the purpose. Over time, the signs of this kind would include the 2 initials (surname and forename), or all the letters of the name, set within a graphic design more or less varied.

In “our” document, the drawing of the notary’s sign is rather rough, comparable to the hasty script, which sometimes sacrifices ease of legibility for speed of production. The result appears to be a professional product by a scribe mostly in a hurry. One is entitled to wonder if the notary guessed that his client(s) in this case might not recognize the difference between written product as such and quality of writing skill.

Docketing

The dorse of the leaf carries 2 inscriptions in ink, by different hands, at very different dates. The first is archival, the second apparently mercenary.

At the ‘top’ of the verso (turning the document vertically on its end), a partly abraded 2-line medieval inscription in Italian roughly written in brown ink describes the contents as a Carta de .atra Con. . . V . / di bo[.?]e da Casana mascl’ — (‘Charter . . . from Casana . . .’).

At the ‘bottom’, the early modern entry in dark brown ink stands close to the right-hand corner. Using Arabic numerals, it proclaims the date 1305 in the enlarged first line and 25 oct[?] in smaller script in the second line.

Provenance

According to the owner’s records, the document was acquired by purchase from the Libreria Leo S. Olschki in Florence, Italy, for US ‘$10’ on 20 June 1972, along with 4 other items of other prices (including Budny Handlist Numbers 2, 7, and 18; the last item is not yet identified).

The travels from its production by a notary of Cesena in 1305 to its sale in Florence in 1972 remain unknown. The stains and rodent-nibbled edges acquired during storage over time provide unwritten, and mute, testimony from those stages.

A few contextual clues appear in the survey by Don C. Skemer (1992) of medieval and early modern notarial documents from Italy acquired between the 1890s and the 1930s by the father-and-son collectors William T. Scheide and John Hinsdale Scheide, and now in the Scheide Library at Princeton University Library, from (among others) the Florentine publisher and antiquarian dealer Leo Samuel Olschki (1861–1940), founder of the firm Leo S. Olschki Editore. For example, this survey usefully considers the natures of the notarial documents, the history of the Italian notariate, the history of record-keeping and archival practices in Italy during the medieval and early modern periods, the likelihood of the preservation of unique information in surviving notarial documents, and some routes by which such documents ‘fell into the possession of antiquarian dealers like Leo S. Olschki’ (page 35).

Although at a different date than those collectors, this document found its way to the United States through one of that firm’s clients, visiting the shop on a Florentine visit. For a while, including in my studio for photography, conservation, and research, the document likewise spent some time in Princeton, although not at the University.

Now it enters a wider world of examination and study.

*****

Bibliographic Sources Cited and Suggestions for Further Reading or Viewing

Bold designates sources cited above. Within a vast and specialized field, the bibliographical citations in the works suggested here provide further directions for study and instruction. An emphasis upon the forms and evolution of notarial signs, from the medieval period onward, may help to situate this case within the larger context of its variable genre, and not only among practices of its own date and region.

Mildred Budny, Handlist (2014–)

Bianca Fadda, “La pergament relative alla Sardegna nel Diplomatico Alliata dell’Archivio di Stato di Pise (parte prima)”, Archivio Storico Sardo, 46:1 (2009), 83-506

Alan Friedlander, ‘Signum meum apposui: Notaries and their Signs in Medieval Languedoc’, Chapter 6 in The Experience of Power in Medieval Europe, 950–1350, edited by Robert F. Berkhofer III, et al. (2005), pages 93–117

Bernard Fourniaux, ‘Les notaires du Périgord et leur seing manual’, Gnomon. Revue internationale d’histoire du notariat (1990), 1–13

Armando Petrucci, Notarii: Documenti per la storia del notariato italiano (1958)

Ernst Roschach (1867), ‘Les signets authentiques des notaires de Toulouse du XIIIe au XVIe siècle’, Revue archéologique du midi de la France, 1 (1867), 142–162

Pierre Saliès, ‘Les seings des notaires toulousains au Moyen Age’, Mémoires de la Société archéologique du Midi de la France, 28 (1962), 41–63

Don C. Skemer (1992), ‘Partners and Protocols: Sources of Italian Economic and Social History, 1200–1650’, Princeton University Library Chronicle, 54 (Autumn 1992), 24–38

*****

Do you know of other documents written and notarized by this scribe? Do you know of other records mentioning the individuals, the tract of land, and that of its neighbors? Please let us know.

Next stop: More Material Evidence. Posts to this blog are signaled on its Contents List.

Do you have reports to offer? Please Contact Us.

*****