To Whom Do Manuscripts Belong?

May 26, 2024 in Manuscript Studies

To Whom Do Manuscripts Belong?

Georgi Parpulov

(independent scholar)

[A Guest Blogpost by our Associate, Georgi Parpulov]

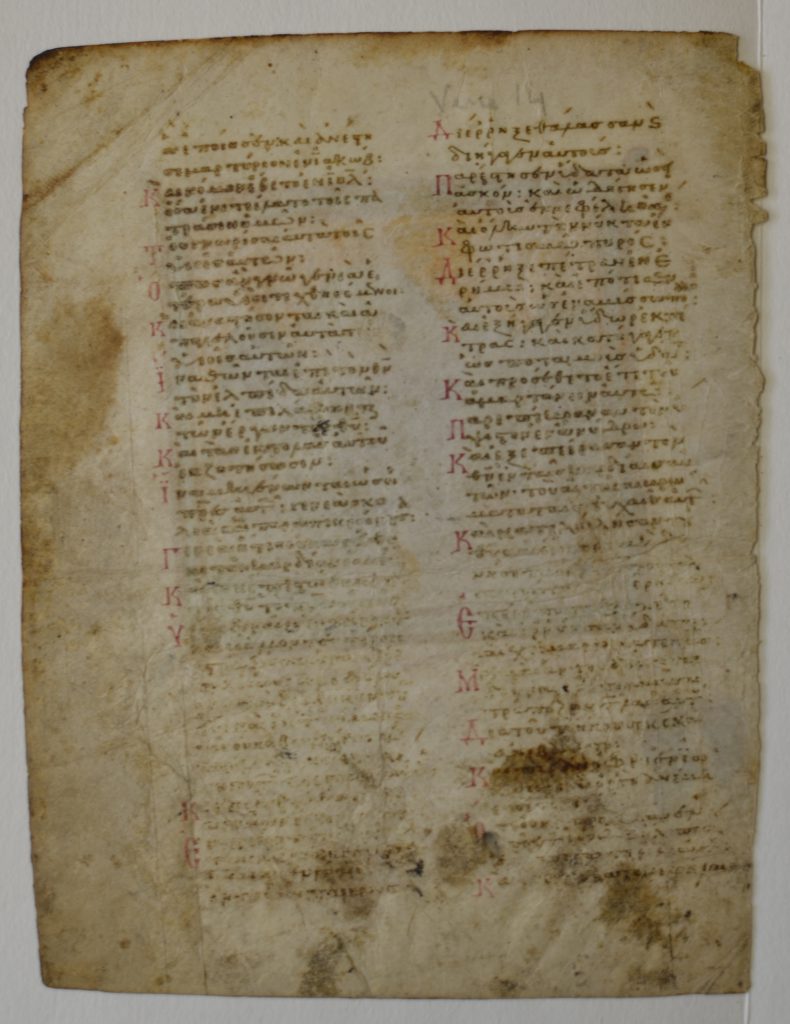

Stray leaf from cod. A 13 of the Lavra on Mount Athos. Recto, detail. Formerly Bath (England), private collection. Present whereabouts uncertain. (Photo: Alexander Saminsky)

A short paper that I published two years ago about dispersed fragments from the library of St Catherine’s Monastery on Mount Sinai prompted a colleague to ask me about ‘manuscripts like these’. ‘What are the ethical issues involved?’, her email went on. ‘Should a collection with fragments from a monastic library offer to return their leaves, for example? Is there any similarity in study of dispersed manuscripts to the study of looted antiquities?’ By way of suggesting possible answers to these questions, I will recount, as accurately and impartially as I can, six distinct series of events.

In March 1917, during World War One, a band of armed men robbed the Greek Eikosiphoinissa Monastery of its library.[1] Because this band was led by the Bulgarian adventurer Todor Panica (1879–1925) and accompanied by the Czech scholar Vladimír Sís (1889–1958), many of the monastery’s manuscripts ended up with public collections in Sofia or Prague. Some, however, remained at first in private hands, and through consecutive sales reached the United States. Two such codices are described, with full provenance information, in a catalogue that Prof. Kenneth Willis Clark (1898–1979) of Duke University published in 1937.[2] In December 2015, ‘the Greek Orthodox Church began sending letters to institutions that possessed the volumes and asked for their return’ (Chicago Tribune of 15 November 2016). The Lutheran School of Theology in Chicago responded by handing over to the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America one of the manuscripts that Clark had catalogued. It was subsequently restituted to Eikosiphoinissa, which nowadays functions as a nunnery. Upon request from the Institut für neutestamentliche Textforschung, a liaison contacted the nuns in 2018 and ascertained the codex’s current shelfmark. High-quality photographs taken in 2010 remain on the website of the Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts.

On 20 June 1960, the abbot of the Dionysiou Monastery on Mount Athos wrote to the local civil authorities in Karyes that some three months earlier a twelfth-century manuscript had been stolen from his monastery.[3] On Good Friday, namely, about eighty German tourists had arrived at Dionysiou and taken turns, divided into two groups, at visiting its library under the supervision of a senior monk who was not feeling well that day.[4] The codex, the abbot wrote, would have been easy to conceal in the clothing or bag of one of them. Its absence was not immediately marked because it was normally shelved behind the frame of a glazed door.[5] A second letter from the same prelate to the same addressee, bearing date 13/26 June 1961, reported the thereto unnoticed absence of another codex (size 315 × 255 × 120 mm), possibly stolen together with the aforesaid one.[6] Two more codices went missing from the monastery’s library ca. 1960, but the circumstances of their disappearance have never been announced. No steps were taken at the time to identify and arrest the suspected thief or to trace the four stolen items. Detailed descriptions and photographs of one were published in 1979, when in was in private hands,[7] and again in 1987, when it had been purchased by the J. Paul Getty Museum.[8] In January 2014, the 1960 theft report came to the attention of the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports, which asked the Getty to return the codex to Greece. The museum complied and proceeded to remove all photos of the manuscript from its website. The book remains accessible through a digitized microfilm made in 1953,[9] where all figural miniatures are covered up with cloth.

While the repatriations of 2016 and 2014 were widely reported, a slightly earlier and somewhat similar case remains, to my knowledge, completely unpublicized. In 2012, an Orthodox Christian in England presented to his local church an illuminated leaf from a Byzantine manuscript, expecting the parish priest to sell it. Once a colleague of mine had emailed me two photographs, it did not take long to identify the manuscript from which the leaf had been detached. Even without information about the date and circumstances of this removal, the priest was determined to do the right thing: he contacted the Greek embassy in London and handed the leaf to their cultural attaché. Presumably it has been reunited with its parent-volume on Mount Athos, but no public announcements to that effect were ever made.

Stray leaf from Cod. A 13 of the Monastery of the Lavra on Mount Athos. Greek New Testament with Psalter and Nine Odes, 11th century: Verso with LXX Psalm 77: 4-23 (Psalm 78: 4-23 in the English Bible). Formerly Bath (England), private collection. Present whereabouts uncertain. (Photo: Alexander Saminsky).

Those smooth restitutions can be contrasted with the recent history of the ‘Archimedes Palimpsest’.[10] From at least 1846 till ca. 1920, the now-famous codex belonged to a metochion (dependency) of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem. It then somehow passed into private hands and was sold at auction to its current owner, an American, in October 1998. A year later the Patriarchate sued for its return. The case was brought before the court of the Southern District of New York and dismissed. ‘Before it filed this lawsuit, the Patriarchate had never asserted claims over other Metochion manuscripts in private hands or announced the disappearance, loss, or theft of any Metochion manuscripts…. In sum, the Patriarchate waited almost seventy years after the Palimpsest was transferred to Mr. Sirieix to bring suit against his heirs [who sold the manuscript in 1998]. The passage of time renders trial of this matter virtually impossible; the Court would be confronted with the Patriarchate’s claim that it clearly possessed the Palimpsest at the beginning of this century against defendants’ claim that they clearly possess it at the end, with little or no evidence of what happened in between.’[11] Since 1999, the palimpsest’s owner has invested generously in its conservation treatment and study. A full set of high-quality digital images has been available for some fifteen years under a Creative Commons license.

My last two stories involve other codices kept in the United States. First we go to Florida. Before The Holy Land Experience, a biblical theme park, closed down in March 2020, all Greek manuscripts of the Van Kampen Collection were housed there. A few of them were on view inside a building called the Scriptorium. When I travelled to Orlando in order to study one that interested me, it was not taken out of its glass case, so I could only see two facing pages. To my joy, the Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts had that same book fully photographed in 2008 and made its photographs viewable on the CSNTM website. They remained online till 2020, when a formal letter from a representative of the Van Kampens asked for their removal.

We finally come to Pennsylvania. The library of Bryn Mawr College houses a Greek Psalter from the second half of the twelfth century, Gordan MS 9. It was first offered for sale in 1906 by Karl Wilhelm Hiersemann, whose catalogue description Vladimir Beneševič reprinted in 1911. Its last known owners are the scholar Phyllis Goodhart Gordan (1913–1994) and her spouse John Dozier Gordon Jr. (1907–1968). They had four children. I examined the codex first-hand in 2003, and more recently, on 4 January 2021, wrote to the college’s Curator for Rare Books and Manuscripts to request digital images of it. I was promptly informed that ‘the manuscript in question does not belong to the library, but is on deposit here. We are not able to provide imaging except with the permission of the owner. . . . I will ask our institutional contact with the owner to forward the request. I am not able to guess whether the owner will agree or refuse – or agree with restrictions.’ I am happy to report that I did obtain photographs, in March 2023. I am prohibited from sharing any of them.

By way of conclusion, I must add to the dry facts some general reflections ‘about the state of the field’. Needless to say, from this point on I can only speak for myself. I am not a tenured academic, so I do not absolutely have to study manuscripts for a living. Even so, I am a scholar of sorts, the kind of scholar who is interested in books as objects (rather than just in the texts that they transmit): I want to examine the handwriting, the decoration, the physical structure of a volume. And there has never been a better time than now to study codices from this angle. Various institutions have placed millions of digital images online. Many a library will permit readers to photograph a manuscript they are studying. Collectors want to have their possessions accessed and catalogued.

Thinking of this, I just do not see how property law can be applied to manuscripts without due reflection. The owner of any physical object has the legal right to limit other persons’ access to it: a monastery’s abbot and librarian are not obliged to let me see a book in their custody, photographs once publicly visible may be hidden from view, and so on. Some codices happen to be very expensive: the Archimedes Palimpsest once fetched over $2,000,000 at auction and would almost certainly fetch more nowadays. But these are not just ordinary valuables, they are significant remnants from our common past. Why should a manuscript restituted become a manuscript hidden? Monks or nuns who have managed to reclaim the nineteenth-century content of their libraries ought to remember the gospel: ‘no one after lighting a lamp covers it with a jar or puts it under a bed’. It is bizarre that things as simple as the shelfmark or even the current whereabouts of a leaf sent back to Greece cannot be easily ascertained. It is equally weird to see American owners struggle to keep their manuscripts out of sight for fear of possible restitution claims.

On 23 June 1964, Pope Paul VI told his college of cardinals: ‘Accepting the request of Constantine, Orthodox Metropolitan of Patras, St Peter’s Basilica will return to his see a priceless relic: that of the sacred head of St Andrew the Apostle. This precious relic was entrusted to Our predecessor Pope Pius II, the famous Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini, who received it under peculiar historical circumstances on 12 April 1462 in order that it be worthily kept next to the tomb of Andrew’s brother the Apostle Peter with the intention that it might one day, God willing, be sent back.’ The head was duly returned to Greece three months later. Countless Christians ceaselessly venerate it, and if I ever visit Patras, I shall not be stopped from doing the same. So should a collection with fragments from a monastic library offer to return their leaves? I might as well directly address the possessors or custodians of such relics: If you believe that manuscripts fall in the same class of objects as human remains, then yes, go ahead and return them to those whom you deem to be their rightful heirs. Fiat iustitia, et pereat mundus.

————————————

[1] An eyewitness account by the monastery’s abbot Neophytus is printed in K. E. Tsiakas, Ἱστορία τῆς Ἱερᾶς Μονῆς Εἰκοσιφοινίσσης Παγγαίου (Drama 1958) 40–41.

[2] K. W. Clark, A Descriptive Catalogue of Greek New Testament Manuscripts in America (Chicago 1937) 51–53, 104–106.

[3] Διὰ τοῦ παρόντος καὶ μετὰ πολλῆς τῆς λύπης μας ἀναφέρομεν Ὑμῖν, ὅτι ἐκ τῆς Βιβλιοθήκης τῆς Μονῆς μας ἐκλάπη πρὸ τριμήνου περίπου, ὡς συμπεραίνομεν, ὁ ὑπ᾽ ἀριθ. 8 περγαμηνὸς χειρόγραφος Κώδιξ (sic) τοῦ 12ου αἰῶνος . . .

[4] Τὴν Μ. Πέμπτην προσήγγισεν εἰς τὴν Μονήν μας τὸ ἀτμόπλοιον “ΑΔΡΙΑΤΙΚΗ” μὲ Γερμανοὺς περιηγητάς, ἐξ ὧν περὶ τοὺς 80 ἀνῆλθον εἰς τὴν Μονήν. Περὶ τῆς ἐλεύσεώς των εἶχομεν προειδοποιηθῆ ἐκ Καριῶν καὶ Δάφνης καὶ ἐπειδὴ ἦλθον περὶ ὥραν 12ην μεσημβρινήν, ὅτε ἐτελεῖτο ἡ θεία λειτουργία, ἐπεσκέφτησαν μόνον τὴν Τράπεζαν τοῦ φαγητοῦ καὶ τὴν Βιβλιοθήκην εἰς δύο ὁμάδας, λόγω στενότητος χώρου. Κατὰ τὴν ἐπίσκεψίν των εἰς τὴν Βιβλιοθήκην περιευρίσκετο καὶ ὁ Ἐπίτροπος Γ. Θεόκλητος, καίτοι ἀσθενής, πρὸς ἀσφάλειαν. Διστυχῶς ἡ εἴσοδος 40 περίπου ἀτόμων εἰς τὸν περιωρισμένον χῶρον τῆς Βιβλιοθήκης καὶ ὁ ὡς ἐκ τούτου συνωστισμὸς διηυκόλησε τοὺς κλέπτας . . .

[5] Ὁ Κῶδιξ εἶναι 30 πόντων ὕφους, 20 πλάτους καὶ 4–5 πάχους καὶ ὡς ἐκ τούτου εὐκόλως ἀπεκρύβη εἰς τὸν κόλπον ἢ τὴν τσάνταν τοῦ κλέψαντος. Ἡ θέσις του ἦτο εἰς τὸ ἄκρον τῆς θυρίδος καὶ σχεδὸν ἐκαλύπτετο ἀπὸ τὸ σανίμα (sic) αὐτῆς, ἐξ οὗ καὶ δὲν ὑπέπεσεν ἐγκαίρως εἰς τὴν ἀντίληψιν τοῦ Βιβλιοθηκαρίου ἡ ἀπουσία του.

[6] Ἀπαντῶντες εἰς Ὑμέτερον ἔγγραφον ἀπὸ 10.7.61 καὶ ὑπ᾽ ἀριθ. 1222.Γ´, ἔχομεν τὴν τιμὴν νὰ ληροφορήσωμεν Ὑμᾶς, ὅτι ὁ ἐν αὐτῷ ἀναφερόμενος περγαμηνὸς Κῶδιξ τῆς Βιβλιοθήκης μας ὑπ᾽ ἀριθ. 49, . . . ἔχει ἐξαφανισθεῖ ἐκ τῆς Βιβλιοθήκης μας, καὶ ἡ ἐξαφάνισίς του ἐγένετο ἀντιληπτὴ ἀπὸ ἔτους. Τὸν χρόνον τῆς ἐξαφανίσεώς του δὲν δυνάμεθα νὰ προσδιορίσωμεν. Ὑποθέτομεν ὅμως, ὅτι δὲν ἀπέχει τῆς διετίας καὶ ἴσως νὰ ἐκλάπη συγχρόνως μὲ τὸν ἄλλον, τὸν ὑπ᾽ ἀριθ. 54, περὶ τοῦ ὁποίου Σᾶς ἀνεφέρομεν τότε ἀμέσως.

[7] A. von Euw, J. M. Plotzek, Die Handschriften der Sammlung Ludwig, I (Cologne 1979) 159–163 with figs 56–63.

[8] R. S. Nelson, ‘Theoktistos and Associates in Twelfth-Century Constantinople: An Illustrated New Testament of A.D. 1133’, The J. Paul Getty Museum Journal 15 (1987) 53–78.

[9] E. W. Sanders, ‘Operation Microfilm at Mt. Athos’, Biblical Archaeologist 18 (1955) 21–41, at 22 and 30.

[10] K. J. Carver, ‘The Legal Implications and Mysteries Surrounding the Archimedes Palimpsest’, American Journal of Legal History 47 (2005) 119–160.

[11] The Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem vs. Christie’s Inc., No. 98 Civ. 7664 (KMW), 1999 WL 673347 (S.D.N.Y. 30 August 1999).

*****