Lead the People Forward (by Zoey Kambour)

February 13, 2022 in Manuscript Studies, Uncategorized

Lead the People Forward:

The Contemporaneity

of the Medieval Iberian Haggadah

Zoey Kambour, MA

15 February, 2022

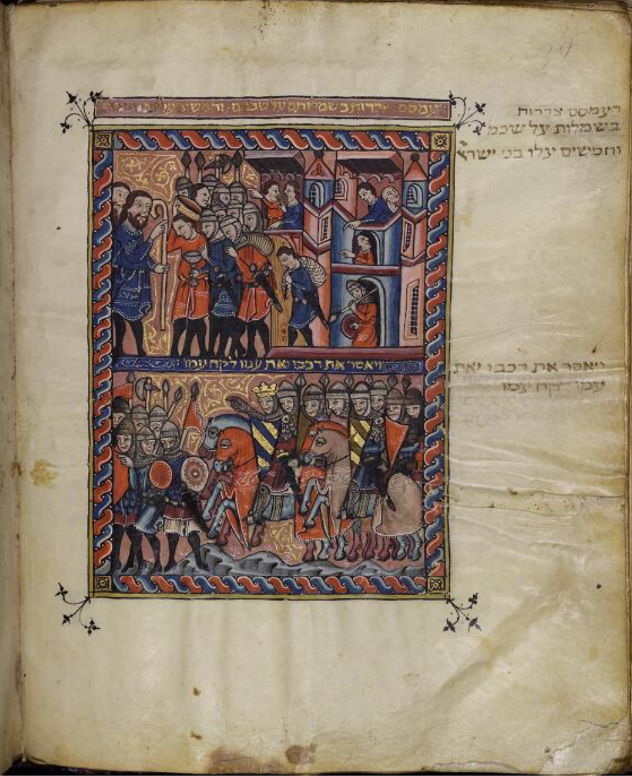

Pursuit by the Egyptians. Detail of Figure 4 (see Figure 4b below). Manchester, John Rylands Library, Rylands Heb. MS 6, fol. 18v, lower. Copyright of the University of Manchester.

[Editor’s Note: This blogpost, by GuestBlogger, Zoey Kambour, is published through the process of peer review by three expert reviewers, each of whom we thank. Thanks are due to the owners of the manuscripts and photographers for permission to reproduce the images here of the medieval manuscripts and architectural structures.

About Zoey, see linkedin.com, uoregon.academia.edu/ZoeyK (with CV), and below. We thank Zoey for proposing to contribute to our blog, preparing this essay from on-going research interests and projects, joining the peer-review process, responding to questions and suggestions, completing the presentation for publication in this format, and obtaining the permissions to reproduce the illustrations here. Congratulations!

Zoey’s essay in the format of a blogpost presents its scholarly structure with Text, interlinked Notes, Acknowledgments, Zoey Kambour’s Biography, and Figures. All the full-size Figures appear in a group at the end, with details along the way.]

“Lead the People Forward”

Passover is a holiday that focuses on the personalized retelling of Exodus — the second book in the Torah, which tells the story of the plight, liberation, and departure of the Israelites under the prophet Moses in Egypt. In this retelling, the participants must see themselves as if they were liberated from Egypt.[1] In addition, the exercise facilitates reflection on how the story of Jewish liberation applies to the current moment. During a time of stress and loss, such as the current pandemic, Passover is a deeply unifying holiday; it reminds the Jewish people of their deep connection to each other, despite the quarantined distance, through their suffering and fight for freedom. Passover conveys a message of hope that applies to any current moment.

The Haggadah (plural Haggadot), the text recited at Seder, is not liturgical, but rather a guide. The participants follow the order of prayers and interactions with the ritual foods displayed on the Seder plate. After the Seder, Exodus is retold in the Maggid portion of the Haggadah.[2] However, unlike a standard liturgical text, the worshippers are encouraged to ad lib, improvise, and add their own unique spin upon the story of Exodus during the performance.

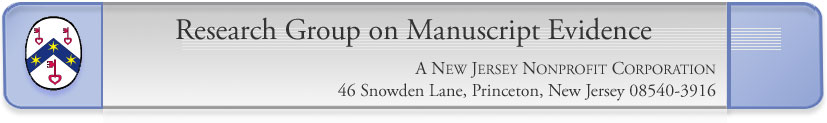

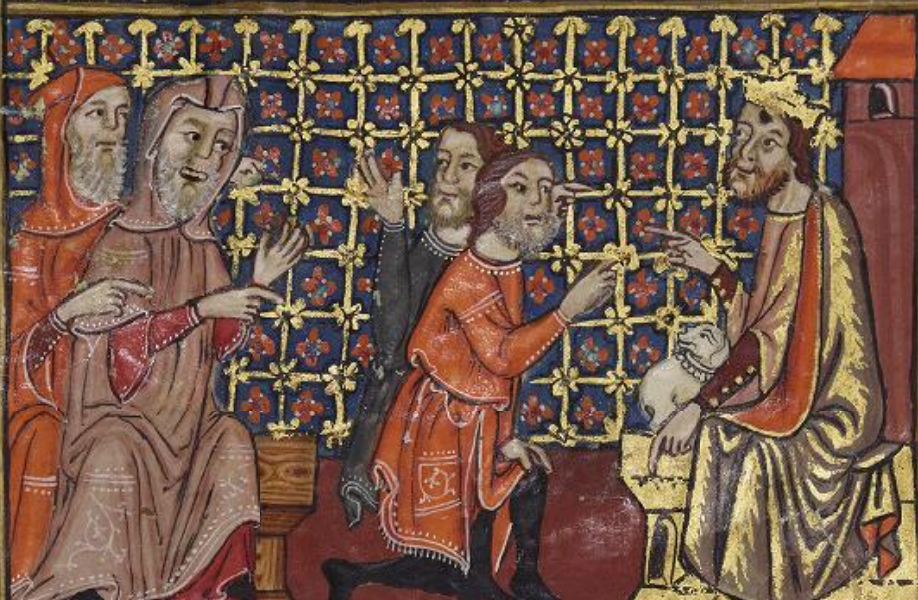

Figure 1. Rylands Haggadah. Manchester, John Rylands Library, Rylands Heb. MS 6, fol. 15v. Copyright of the University of Manchester.

During the high and late medieval period in the Iberian Peninsula, many Jewish people lacked literacy in Hebrew. While the rituals and prayers are written in Hebrew, many surviving medieval Haggadot contain rich illuminations in the Maggid, enabling the illiterate to recite and personalize the story of Exodus, while still faithfully conveying it.[3] Through reciting, performing, and personalizing the Haggadah, Jews connect the hay-yamim ha-hem (“in those days”) with the z’man ha-zeh (“in this time”).[4]

The performance of the Haggadah is not the only means of tying the contemporary moment to Exodus; the Biblical illuminations and marginalia in medieval Iberian Haggadot additionally aid in this association. In late thirteenth- and fourteenth-century Haggadot shel Pesaḥ (הגדה של פסח or “Haggadot for Passover”), such as the Rylands Haggadah (Manchester, John Rylands Library, Rylands Hebrew MS 6) and the Golden Haggadah (London, British Library Add. MS 27210), the visual anachronism of contemporaneous clothing and architecture present in the illuminations of a biblical story [5] The images not only situate it in the current moment, but may also serve as a commentary against Christian rulers through the presence of the heraldic colors of Barcelona and the monarchical clothing of the Pharaoh.

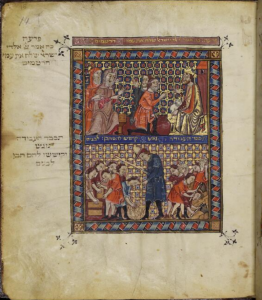

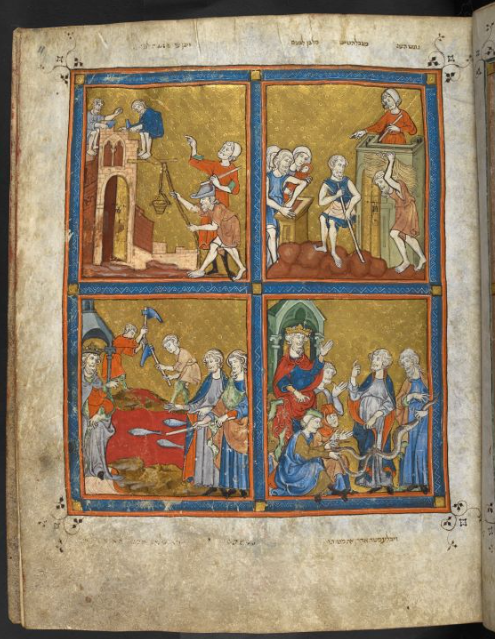

Figure 2. Golden Haggadah, Catalonia, 1329–1330. © British Library Board, London, British Library, Add MS. 27210, fol. 11r.

Jews in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth century, although segregated to their communally governed communities called aljamas, held prominent places in Christian courts for their financial and intellectual abilities, a practice that began in al-Andalus as early as the Caliphate of Córdoba in the late tenth and eleventh century.[6] This service to Christian crowns legally protected these elite Jews from persecution, but branded them as property of the crown.[7] Aside from the privilege of protection awarded to the Jews of the Christian courts, anti-Semitism remained prominent throughout the Christian kingdoms. However, nothing brought on a wave of persecution quite like the devastation caused by the fourteenth-century plague.[8]

To best demonstrate the contemporaneous application into Exodus, a focus is placed on the visual anachronism of the garments of the biblical figures and the architecture situated within or framing the illuminations.[9] Almost every figure wears a saya (also known as a gonela in Aragon), which is a gown worn over a base camisa, or chemise. The saya could be worn as either a loose version, fastened at the neck with buttons, or a closely fitted version where there is lacing at either the back or the side of the garment. Sayas could be sleeved or sleeveless and were frequently belted. Over the sayas, as shown on the depictions of the Pharaoh, is a pellote which is a kind of surcoat. In addition to the pellote, the Pharaohs wear a medieval European golden crown. The attendants often wear a hooded garment called a capirote. Another distinguishing costume is the headwear. The most common is the cofia, a fabric cap that can be worn, for women, with a fillet that covers the ears. Other common forms of headwear include sombreros (any brimmed hat), capiellos (a cylindrical hat), and boinas (a round hat with no brim).[10] These styles of clothing are not limited to the fourteenth century — many, if not all, of these types of clothing and hats can be found in the thirteenth-century manuscript of the Cantigas de Santa Maria.[11]

Figure 1a. Moses and Aaron before Pharaoh. Manchester, John Rylands Library, Rylands Heb. MS 6, fol. 15v, upper panel. Copyright of the University of Manchester.

Figure 2a. Moses’ Staff transforms into a Snake. Golden Haggadah, Catalonia, 1329–1330. © British Library Board, London, British Library, Add MS. 27210, fol. 11r, lower right.

The upper panel of Rylands folio 15v demonstrates most of these clothing elements (Figures 1 and 1a). Kneeling in front of the Pharaoh, who dons a pellote and golden trefoil crown, Moses and Aaron wear sleeved and belted sayas of red and blue. The Pharaoh’s attendants behind Moses and Aaron wear capirotes. In a similar scene in folio 11r from the Golden Haggadah, as the staff turns into a snake, Moses and Aaron wear capes over their sayas, the Pharaoh wears the same pellote over a saya in addition to a golden crown (Figures 2 and 2a). The scene differs from the former only in its presentation of the attendants, one of whom wears a cofia with a felt cap while the other wears a capirote.

Figure 3a. Pursuit of the Egyptians. Golden Haggadah, Catalonia, 1329–1330. © British Library Board, London, British Library, Add MS. 27210, 14v, lower right.

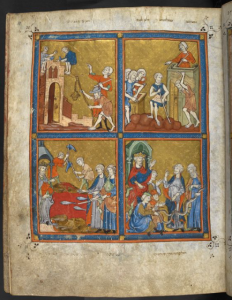

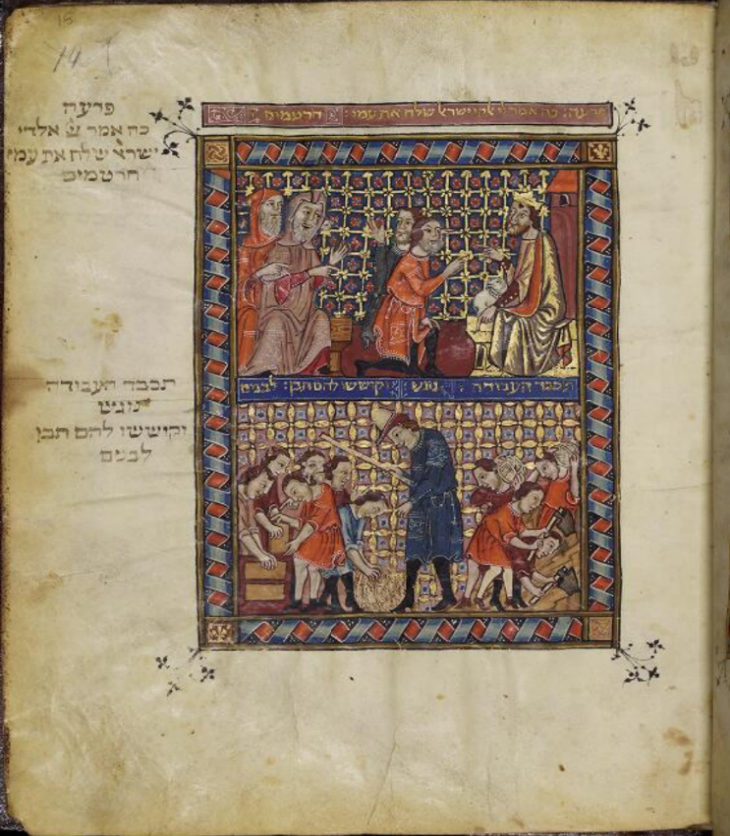

The clearest examples of contemporary imagery are present in the scene of Exodus 14:8 — Pursuit of the Egyptians, as seen in folio 14v in the Golden Haggadah and folio 18v in the Rylands Haggadah (Figures 3 and 4). In the lower panel of folio 18v (Figure 4a) in the Rylands Haggadah, the Pursuit of the Egyptians features a procession of armed equestrian figures led by the crowned figure, all wearing high medieval armor.[12] One of the shields carried by the equestrian figures bears red and gold stripes, representing the crown of Aragon, while another shield with gold and blue stripes possibly represents the House of Bourbon.[13] Folio 14v in the Golden Haggadah (Figure 3a) similarly shows a group of equestrian knights led by the crowned Pharaoh. Another allusion to contemporaneous politics is similarly made in the colors of one of the shields, which bears the symbols of the House of Leon.[14] The presence of the heraldry and monarchical dress visually conflates Pharaoh and his soldiers with secular leaders.

Pursuit of the Egyptians. Detail of Figure 4. Manchester, John Rylands Library, Rylands Heb. MS 6, fol. 18v, lower. Copyright of the University of Manchester.

Figure 6. Entrada del Castillo Templario de Ponferrada, El Bierzo, 1178. Picture by Jgaray, Wikipedia, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5/legalcode , August, 2006.

Figure 5. Lancet windows in the Santa Maria de Léon Cathedral, Léon, ca. 1205. Photo by Michael Boyles, 2015. Reproduced by permission.

Rather than pyramids and nomadic structures

, which one might expect in images of Egypt, the architecture in the folios manifest as late Romanesque and early Gothic architecture. For example, the Pharaoh in the top right section of folio 11r from the Golden Haggadah (Figure 2) sits underneath a trefoil pointed arch, supported by columns topped with Corinthian capitals. On the same folio to the left of the aforementioned scene, the Israelites build a structure than includes a double arch trefoil window, such as the window lancets at the Santa Maria de Léon Cathedral (Figure 5). In the Rylands Haggadah, the Israelites flee from a multi-turreted and crenelated military structure, similar to the twelfth-century castle, Castillo de Ponferrada in Leon—Castile (Figure 6).

Through the visually anachronistic depiction of medieval clothing and architecture in the Exodus illuminations, the medieval Iberian Haggadah emphasizes the reflection of the current moment through Exodus. While the Haggadah, regardless if it is from the fourteenth or twenty-first century, aids in the retelling of Exodus through its personalization, imagery, and guidance, the hope for freedom expressed in Exodus is applicable to any contemporary era of unrest.

*****

Notes

[1] Based upon Maimonides’ compilation of Jewish law in the Mishneh Torah, the text says: “In every generation one is obligated to show oneself (l’harot et atzmo) as if one has, just at that moment, been released from enslavement in Egypt.” Quoted from: Julie A. Harris, “Making room at the table: Women, Passover and the Sister Haggadah (London British Library, MS Or. 2884)”, in Journal of Medieval History, vol. 42, 1, (2016) 131–153.

[2] A maggid is a person, typically a para-rabbi, who skillfully narrates the Torah and other religious stories. The Maggid portion of a Jewish holiday, today, is the narrative re-telling of a part of the Torah.

[3] Marc Michael Epstein, The Medieval Haggadah: Art, Narrative, and Religious Imagination (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011), 14.

[4] Ibid, 149.

[5] Library online catalogue entries and digital facsimiles:

- Manchester, John Rylands Library, Rylands Hebrew MS 6;

- London, British Library Add. MS 27210.

[6] Benjamin R. Gampel, “Jews, Christians and Muslims in Medieval Iberia: Convivencia through the Eyes of Sephardic Jews,” in Convivencia: Jews, Muslims, and Christians in Medieval Spain (New York: The Jewish Museum, 1992), 23. David Nirenberg documents that this practice began as early as Alexandrian Egypt: Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2013), 22–25.

[7] Gampel, “Jews. Christians and Muslims”, 22.

[8] David Nirenberg, “Epilogue: THE BLACK DEATH AND BEYOND” in Communities of Violence: Persecution of Minorities in the Middle Ages. (Princeton: Princeton University Press: 1996), 231-250.

[9] Visual anachronism can mean a few different things, especially in regards to the medieval period, but in this context I am using visual anachronism to mean the incongruency between the contemporaneous elements juxtaposed against more historically accurate ancient models. See: Linde Brocato, “Visual anachronism,” Encyclopedia of the Medieval Chronicle, R.G. Dunphy ed. (Brill, Leiden and Boston, 2010), 1483–1485.

[10] Grace M. Morris, “Jessamyn’s Closet — Costume in Medieval and Renaissance Spain and Portugal,” Blog, Jessamyn’s Closet (blog), August 9, 2005; Margaret Scott, Medieval Dress & Fashion (London: British Library, 2007).

[11] Four parts of this manuscript survive in three different librariess in Spain and Italy (with some parts shown online in digitized facsimiles):

- Códice de Toledo, Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional de España, MS 10069;

- San Lorenzo de El Escorial, Biblioteca de El Escorial, MS T.I.1;

- Códice de Florencia, Florence, Biblioteca Nazionale, MS br 20;

- Códice de los músicos, Biblioteca de El Escorial, MS B.I.2.

[12] Scott, Medieval Dress & Fashion, 70.

[13] Raphael Loewe, The Rylands Haggadah: A Medieval Sephardi Masterpiece in Facsimile. An Illuminated Passover Compendium from Mid-14th-Century Catalonia in the Collections of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester with a Commentary and a Cycle of Poems. (London: Thames and Hudson, 1988) 13.

[14] Bezalel Narkiss, Hebrew Illuminated Manuscripts in the British Isles: A Catalogue Raisonné (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982) 43.

*****

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Mildred Budny and the rest of the Research Group on Manuscript Evidence for their support and guidance during the stages of this blog post. I would like to thank my reviewers, Linde Brocato, Julie Harris, Maile Hutterer, and Marla Segol, for their helpful and productive comments, and for their constructive criticism in my first peer-review process. I wish to express thanks to the British Library, the Rylands Library, and Michael Boyles at the University of Northern Florida for their permission to use their images. I thank the University of Oregon ARH 525 class, “Medieval Identity”, for the opportunity to first conduct this research, and for the student and instructor feedback on this project.

Biography

Zoey Kambour is the Post Graduate Fellow in European & American Art at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art in Eugene, OR. They hold a MA in art history from the University of Oregon, and BAs in art history and music performance from Lewis & Clark College. They will be pursuing their doctoral study this fall (2022) in art history, at a university TBD. They are a specialist in medieval manuscript illumination and medieval Iberia.

Bibliography

Brocato, Linde. “Visual anachronism,” in Encyclopedia of the Medieval Chronicle, 1483–1485. Ed. R.G. Dunphy. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2010.

Epstein, Marc Michael. The Medieval Haggadah: Art, Narrative, and Religious Imagination. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011.

Gampel, Benjamin R. “Jews, Christians and Muslims in Medieval Iberia: Convicencia through the Eyes of Sephardic Jews.” In Convivencia: Jews, Muslims, and Christians in Medieval Spain, 11–38. New York: The Jewish Museum, 1992.

Harris, Julie A. “Making room at the table: Women, Passover and the Sister Haggadah, (London British Library, MS Or. 2884)” in Journal of Medieval History, vol. 42, 1, (2016) 131–153.

Loewe, Raphael. The Rylands Haggadah: A Medieval Sephardi Masterpiece in Facsimile. An Illuminated Passover Compendium from Mid-14th-Century Catalonia in the Collections of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester with a Commentary and a Cycle of Poems. London: Thames and Hudson, 1988.

Morris, Grace M. (“Mistress Maddalena Jessamyn di Piemonte”),“Jessamyn’s Closet — Costume in Medieval and Renaissance Spain and Portugal.” Blog: Jessamyn’s Closet (blog), August 9, 2005.

Narkiss, Bezalel. Hebrew Illuminated Manuscripts in the British Isles: A Catalogue Raisonné. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982.

Nirenberg, David. “Epilogue: THE BLACK DEATH AND BEYOND.” Communities of Violence: Persecution of Minorities in the Middle Ages. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996, 231–250.

——— Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2013.

Scott, Margaret. Medieval Dress & Fashion. London: British Library, 2007.

****

Figures

Figure 1. Moses and Aaron tell Pharaoh the Lord’s Message (upper); the Labors of the Israelites (lower).

Rylands Haggadah, Catalonia, Spain, mid-14th century. Manchester, John Rylands Library, Rylands MS Heb. 5, folio 15v. Copyright of the University of Manchester.

Figure 1. Manchester, John Rylands Library, Rylands Heb. MS 6, fol. 15v. Copyright of the University of Manchester.

Fig. 1a: Moses and Aaron tell Pharaoh the Lord’s Message.

Rylands Haggadah, Catalonia, Spain, mid-14th century. Manchester, John Rylands Library, Rylands Heb. MS 6, fol. 15v, upper. Copyright of the University of Manchester.

Moses and Aaron before Pharaoh. Manchester, John Rylands Library, Rylands Heb. MS 6, fol. 15v, lower. Copyright of the University of Manchester.

Figure 2. Labors of the Israelites (upper left and upper right), Plague of Blood (lower left), Moses’ Staff Transforms into a Snake (lower right).

Golden Haggadah, Catalonia, 1329–1330. © British Library Board, London, British Library, Add MS. 27210, fol. 11r.

Golden Haggadah, Catalonia, 1329–1330. © British Library Board, London, British Library, Add MS. 27210, fol. 11r.

Figure 2a: Moses’ Staff Transforms into a Snake.

Golden Haggadah, Catalonia, 1329-1330. © British Library Board, London, British Library, Add MS. 27210, fol. 11r, lower right.

Moses’ Staff. Golden Haggadah, Catalonia, 1329-1330. © British Library Board, London, British Library, Add MS. 27210, fol. 11r, lower right.

Figure 3. The Departure of the Israelites (upper) and the Pursuit of the Egyptians (lower).

Golden Haggadah, Catalonia, 1329–1330. © British Library Board, London, British Library, Add MS. 27210, 14v.

Golden Haggadah, Catalonia, 1329–1330. © British Library Board, London, British Library, Add MS. 27210, 14v.

Figure 3a: The Pursuit of the Egyptians.

Golden Haggadah, Catalonia, 1329-1330. © British Library Board, London, British Library, Add MS. 27210, 14v, lower right.

Pursuit by the Egyptians. Golden Haggadah, Catalonia, 1329–1330. © British Library Board, London, British Library, Add MS. 27210, 14v, lower right.

Figure 4. The Departure of the Israelites and the Pursuit of the Egyptians.

Rylands Haggadah, Catalonia, Spain, mid-14th century. Manchester, John Rylands Library, Rylands Heb. MS 6, fol. 18v. Copyright of the University of Manchester.

Rylands Haggadah, Catalonia, Spain, mid-14th century. Manchester, John Rylands Library, Rylands Heb. MS 6, fol. 18v. Copyright of the University of Manchester.

Figure 4a: The Pursuit of the Egyptians.

Rylands Haggadah, Catalonia, Spain, mid-14th century. Manchester, John Rylands Library, Rylands Heb. MS 6, fol. 18v, lower. Copyright of the University of Manchester.

Pursuit by the Egyptians. Manchester, John Rylands Library, Rylands Heb. MS 6, fol. 18v, lower. Copyright of the University of Manchester.

Figure 4b: The Departure of the Israelites.

Rylands Haggadah, Catalonia, Spain, mid-14th century. Manchester, John Rylands Library, Rylands Heb. MS 6, fol. 18v, upper. Copyright of the University of Manchester.

Departure of the Israelites. Manchester, John Rylands Library, Rylands Heb. MS 6, fol. 1vv, lower. Copyright of the University of Manchester.

Figure 5. An example of lancet windows in the Santa Maria de Léon Cathedral, Léon, ca. 1205. Photo by Michael Boyles, 2015. Reproduced by permission.

An example of a lancet window from the Santa Maria de Léon Cathedral, Léon, ca. 1205. Photo by Michael Boyles, 2015.

Figure 6. El Bierzo, Entrada del Castillo Templario de Ponferrada, 1178.

Picture by Jgaray, via Wikipedia, Creative Commons (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5/legalcode ), August, 2006.

Entrada del Castillo Templario de Ponferrada, El Bierzo, 1178. Picture by Jgaray, Wikipedia, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5/legalcode , August, 2006.

Editor’s Note:

We thank Zoey for this peer-reviewed article joining our blog on Manuscript Studies. In the Contents List for the blog, which arranges the blogposts by category (“Setting the Stage”, “Bits & Pieces”, “Documents in Question”, etc.), Zoey’s article opens a new category, “Books Telling Their Stories”.

We look forward to learning more from Zoey’s continuing research and their engagement with medieval and other materials.

Comments are welcome. You might add your Comment here, reach us via Contact Us, or visit our Facebook Page. We look forward to hearing from you.

Update on 26 March 2022:

We look forward to Zoey’s presentation on another subject for the 2022 Spring Symposium on “Structures of Knowledge” on 2 April.

Update on 28 September 2022:

Zoey presents an update for her presentation in the Spring Symposium with another for the 2022 Autumn Symposium on “Supports for Knowledge”.

****