An Illustrated Leaf from the Shahnameh with a Russian Watermark

August 4, 2021 in Manuscript Studies

An Illustrated Persian Leaf on Paper

from the Shahnameh

(Humai & Darab)

with a Russian Watermark

[Posted on 5 August 2021]

Continuing our examination of Watermarks and the History of Paper, we display an illustrated paper leaf from an illustrated manuscript which has come to our notice. Its owner identified the text, but wondered about the watermark. Responding to our blog, he offered its images for examination.

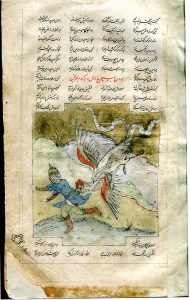

Private Collection, Leaf from a Persian Shanameh. Simurgh and Zal.

Now in a private collection, the detached leaf formerly belonged to an illustrated manuscript in Persian of the Shahnameh or ŠĀH-NĀMA / Šāhnāme (شاهنامه or “Book of Kings”), the renowned epic poem by the Persian poet Abul-Qâsem Ferdowsi Tusi or Ferdowsi (circa 329 – 411 AH / 940 – 1010 CE). This poem, which the poet began to compose circa 977 CE and completed on 8 March 1010 CE, extends for more than 50,000 couplets. Its text recounts the history of the kings and heroes of Persia from mythical times to the overthrow of the Sassanids by the Arabs in the middle of the 7th century.

The importance and popularity of the text ensured that it has circulated in very many copies produced at various times and in various places, manuscripts included. Not all of them survive, and some survive only in pieces.

An earlier post in our blog (see its Contents List) considered a detached leaf from another portion of the epic, from another illustrated manuscript, and in another private collection.

Simurgh and Zal from a Persian Shahnameh.

That leaf illustrates an episode from the fabulous story of the winged creature Simurgh and her adopted human warrior son Zāl. Within a stepped frame set within the page of text, its illustration depicts the large creature as she swoops down to grasp or grab him by the waistband as he flees.

The ‘new’ leaf belongs to a different episode, a different manuscript, and a different style of illustration, in the long and richly varied tradition of illustrations for the Shahnameh or Šāh-nāma in books and other visual arts, and in Persian and other spheres.

Humai and Darab

Among the Episodes of the Shahnameh, the sections devoted to a legendary queen of Iran, Humai or Humay Chehrzad (sections 609–614 in one form of reckoning), recount events of her reign within the legendary Kayanian dynasty. They relate the birth of her son Kai Darab, her abandonment of him as an infant, her recognition of him as an adult as her son, after he had helped to defeat the attacking Romans at the edge of the Iranian Empire. These sections end with her retirement from the throne in favor of him as the next king, Dara I.

The text on the leaf belongs to the episode that recounts how, after “Darab fights against the Host of Rum” (612), “Humai recognises her Son Darab” (613).

The Leaf and Its Illustration

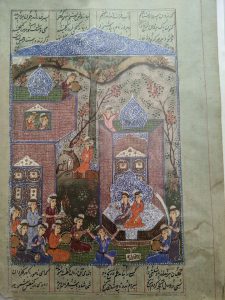

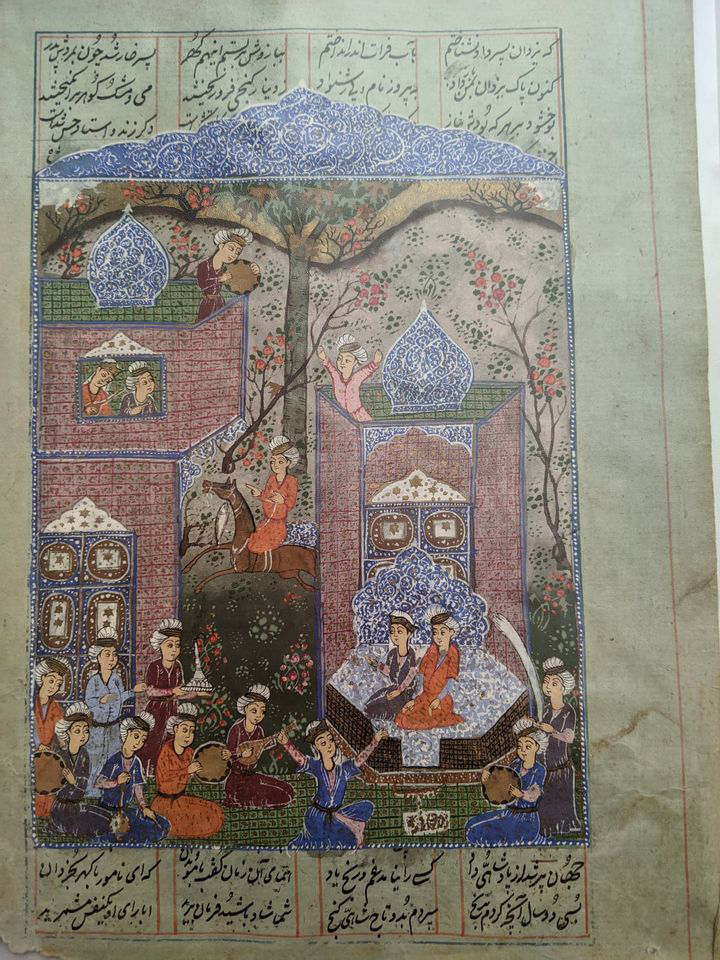

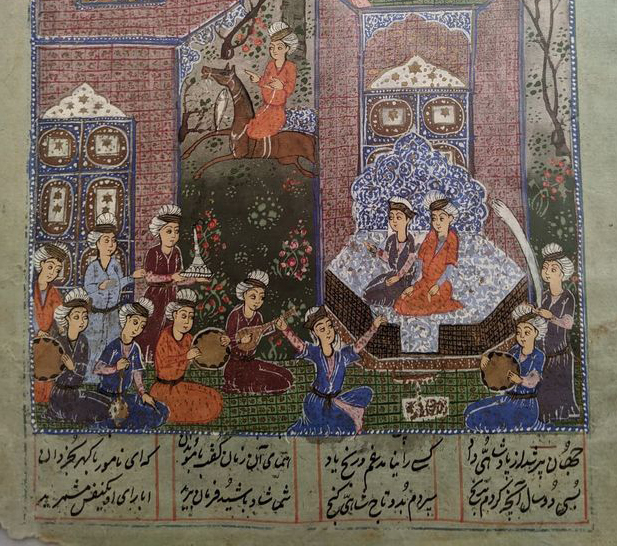

Luke’s Collection, Persian Leaf with Shahnameh volume 5, illustration. Reproduced by permission.

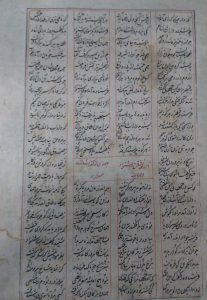

Luke’s Collection, Persian Leaf with Shahnameh volume 5, text page. Reproduced by permission.

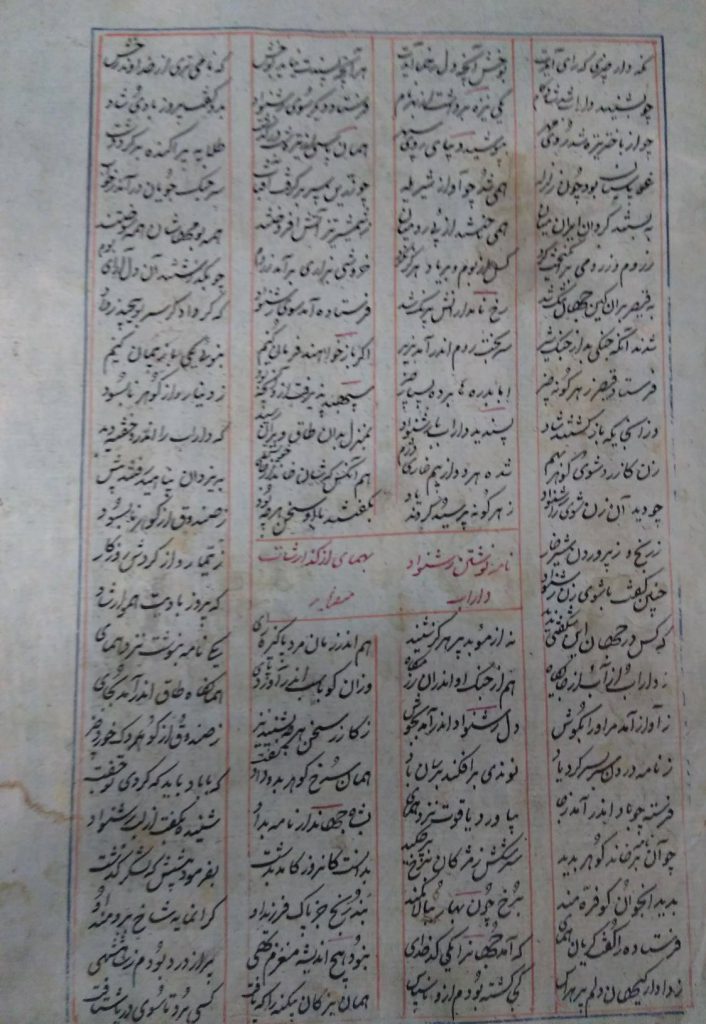

Both sides of the leaf have upright rectangular frames which contain the text and its illustration.

One side of the leaf carries only text. On the other side, the illustration stands within the column, full width, between a few lines of text above and below.

The text of the poem is set out in 4 columns which stand between vertical bounding lines. On the recto, with text alone, the rubricated title occupies a box-like frame centered between the middle pair of columns; they separate their course to accommodate its presence. The title includes the word ‘داراب‘ (‘Darab’) at the lower right.

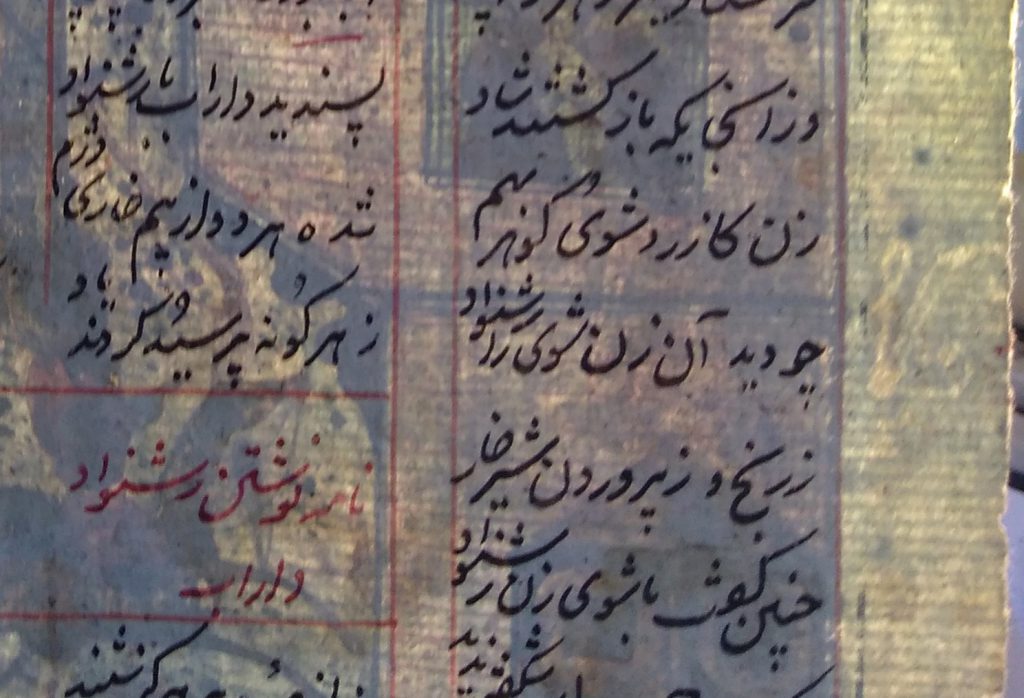

Contrasting with the open background of the columns of script, the fully painted illustration occupies an upright rectangular frame topped by a low subtriangular extension, resembling a decorative canopy. Above the illustration stand 4 lines, or part-lines, of text, in which lines 3 and 4 spread to either side of that riser. Below the illustration stand 2 more lines.

Within a landscape setting, the illustration presents groups of figures in various poses within and outside a pair of tall architectural structures. Seventeen human figures, male and female, appear part-length or full-length and engage primarily in music-making or listening and observing. At the center left, one figure on horseback rides toward the left between the buildings.

The Illustration within the Text

Filling the full width of the framed contour of the page, the illustration nestles below the first three lines of text, to leave space for two more lines of text below it.

Luke’s Collection, Persian Leaf with Shahnameh volume 5, illustration. Reproduced by permission.

The Text Side

Luke’s Collection, Persian Leaf with Shahnameh volume 5, text page. Reproduced by permission.

The Collector

The collector speaks:

I’ve had the page for close to a year, it was found by chance at an auction. It contains parts of section 6 and 7 of the Story of Humai Chehrzad‘s Kingdom (vol. 5 of the Shanameh), where the orphan soldier Darab destroys a Roman encampment, and is recognised by his birth mother, Queen Humai, who resigns from the throne, and makes Darab the new king [Dara I]. At least, that’s my brief account of what occurs.

I’d be more than happy for the item to be documented on your website, you can cite me by my first name (Luke).

Once again I’d like to thank you and your colleagues for taking the time to tell me my manuscript’s story.

The Watermark

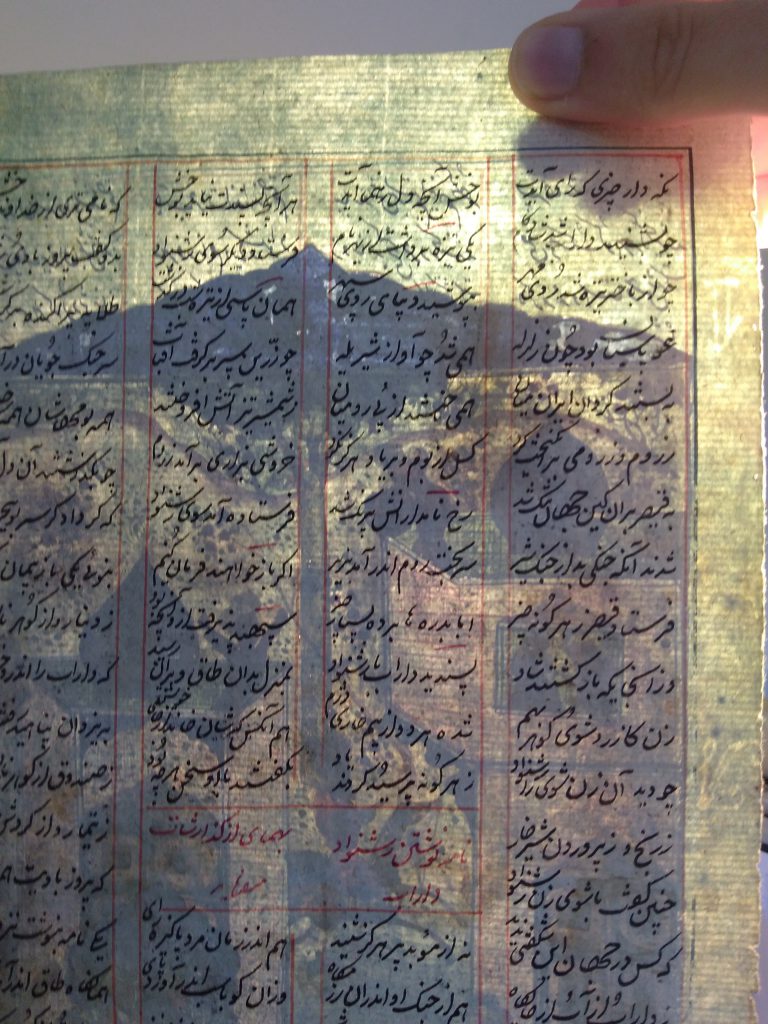

Viewed from the text side, with back-lighting:

Luke’s Collection, Persian Leaf with Shahnameh volume 5, text side with back-lighting. Reproduced by permission.

Viewed from the illustrated side, with back-lighting:

Luke’s Collection, Persian Leaf with Shahnameh volume 5, illustration. Reproduced by permission.

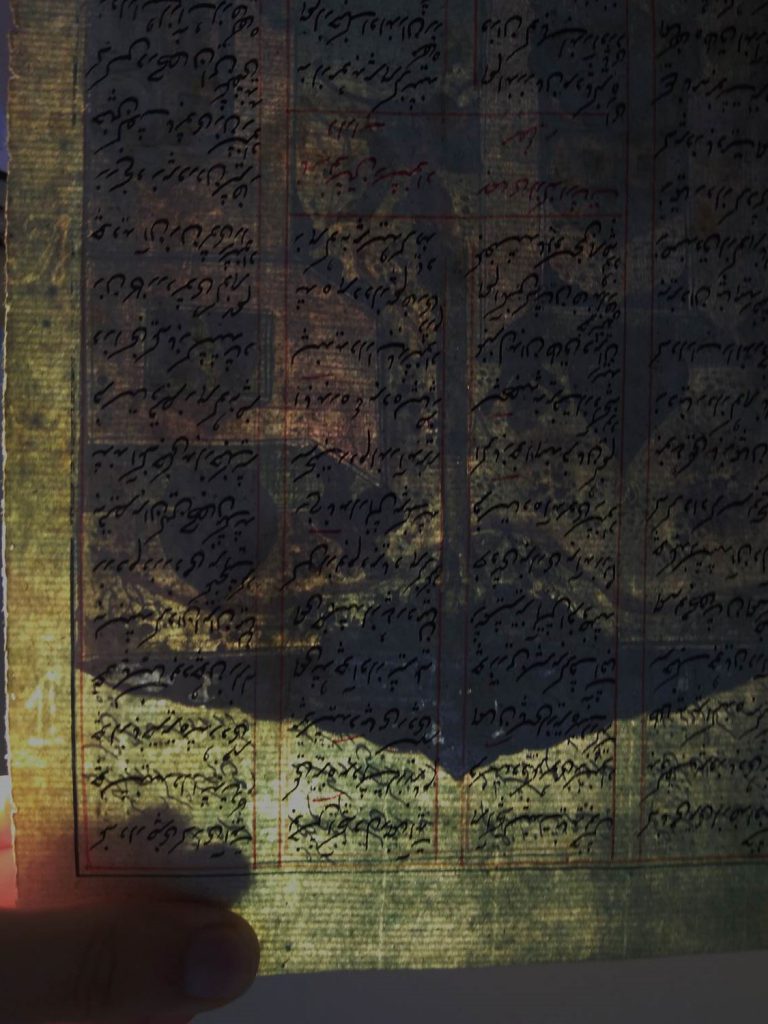

Up close, the Watermark, from both sides of the leaf in turn.

From the Text Side, seen with the text upright:

Luke Collection, Persian Leaf with Shahnameh volume 5, text side of the leaf backlit, with detail of watermark. Reproduced by permission.

From the illustrated side, seen with the text upside down:

Luke Collection, Persian Leaf with Shahnameh volume 5, text side of the leaf backlit, with detail of watermark. Reproduced by permission.

A Russian Watermark

Consulting an expert who has been examining such materials for some time and in various contexts, we received a preliminary response. To whit:

The quick answer is that the paper looks like typical Russian document paper of the sort which they sold in Mongolia as well. It was “official” paper with a dated watermark as a security feature, and presumably a taxation feature; it would have been valid for a year or two, and after that it would have been worthless, so it was sold in quantity to outlying areas such as Mongolia. I have a lot of Mongol and Tibetan MSS and assorted loose leaves with such watermarks ranging from the 1780s to the 1840s. The example looks like either (18x)1 or (18)1x, with a script M from the maker’s initials.

Somewhere I have a lot of examples from Mongolia, but as of tonight they are hiding. I did win two Russian docs from 1816-8 today, which I should be able to use as useful examples.

A Migratory Tale

Learning of this response, Luke allows both it and the images to join our blog.

Here, it might stand as an instructive example of a ‘migratory watermark’,whose paper leaf must have travelled far from the region of its origin through one or more other realms, to find its use in the Persian manuscript. Likewise, that manuscript has experienced travels from its place of origin through (at least) the hands of the seller.

Luke’s Collection, Persian Leaf with Shahnameh volume 5, illustration, lower level. Reproduced by permission.

Do you know of other leaves from this manuscript? If so, do they have watermarks, either this one or some others? Do you have suggestions about the probable date and place of origin?

Please leave your Comments below or Contact Us. We look forward to hearing from you.

*****