Selbold Cartulary Fragments

July 4, 2020 in Manuscript Studies

Selbold Cartulary Fragments

3 Leaves on Paper

Single columns of 38 lines

Circa 28.3 × 210 cm < written area of circa 20.6 × 15.5 cm>

Presumably Stift Selbold or its Region (Hessen) in Germany

Late 14th or early 15th Century

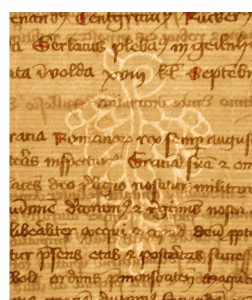

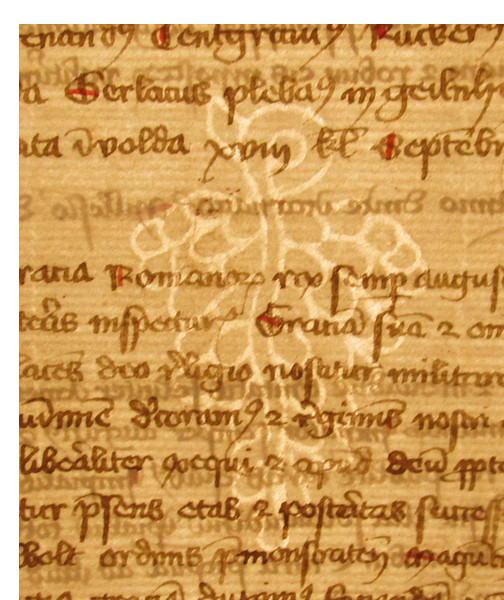

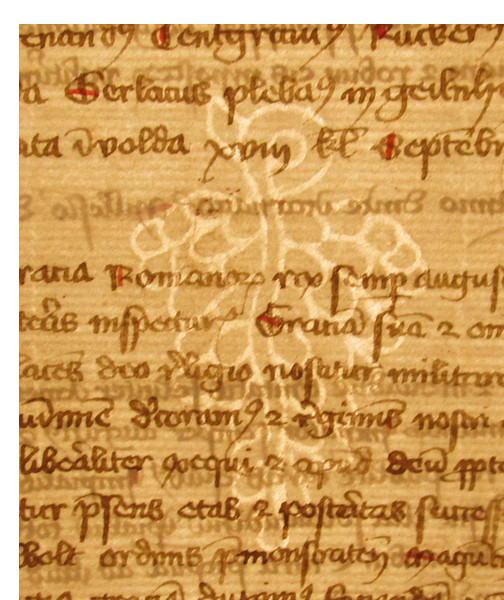

Watermark of Grape Cluster

[Posted on 3 July 2020, with updates]

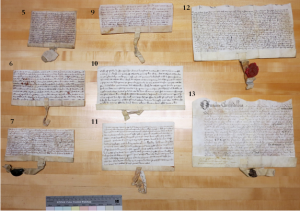

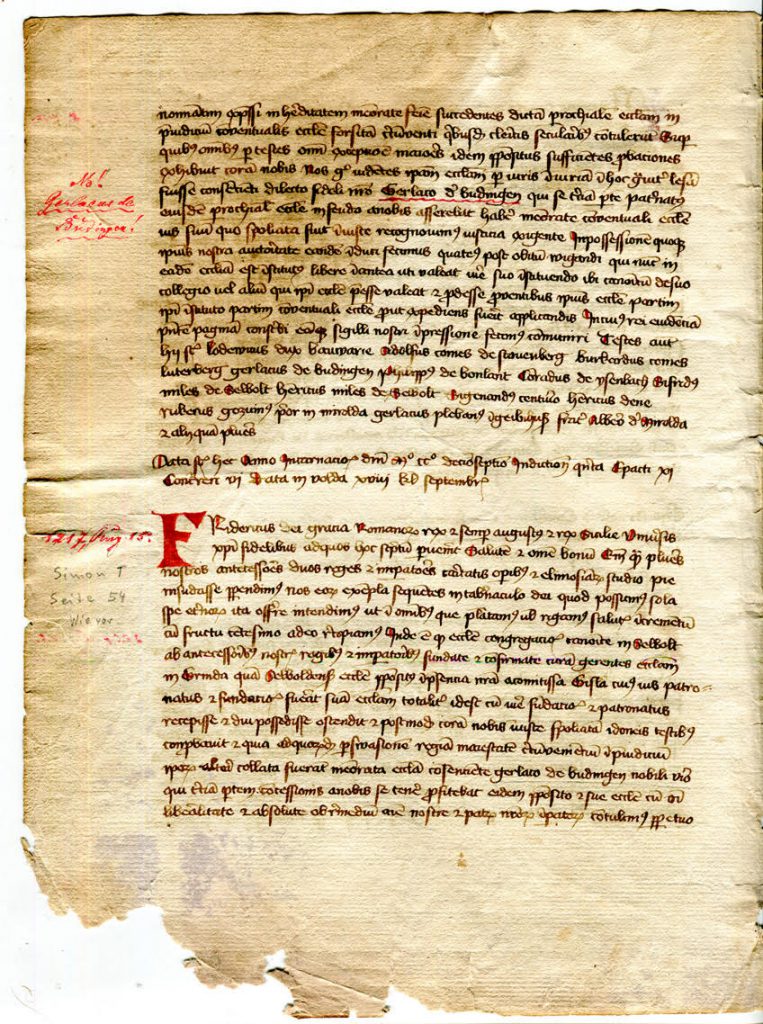

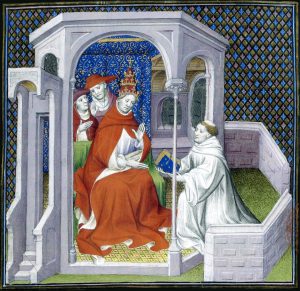

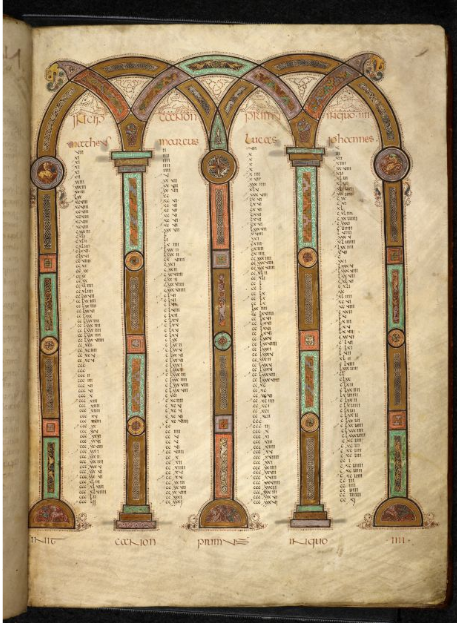

Continuing our blog on Manuscript Studies (see its Contents List), we publish images and descriptions of a set of three leaves from the dismembered paper copy of a Latin cartulary (or codex diplomaticus or Kopialbuch, in Latin and German) of the former Premonstratensian monastery-and-then-abbey of Selbold in Hessen, Germany. The set presents a now-disrupted series of uniform transcriptions in book form of individual dated documents issued by ecclesiastical and secular rulers confirming, or reconfirming, rights and privileges pertaining to that institution and its dependencies.

Purchased from Boyd Mackus in the United States some years ago and now in a private collection, the fragments comprise 1 single leaf and 1 bifolium. We identify them here as folios “1” and “2–3”, using inverted commas or quotation marks to indicate a non-original sequence and location within the former volume. Written by a single scribe with a uniform layout, the leaves contain a late-medieval copy of the texts of 8 documents (not all complete) issued by various authorities in a range from the 12th to 14th centuries. Upon the original pages, even apart from the subsequent disruptions to the text through dispersal of leaves, the transcriptions are set out in sequences that are only partly chronological according to the issued dates of the documents.

Written in ink with elements of red pigment, the text is laid out on the leaves in single columns of 38 lines. One leaf has a watermark.

These leaves deserve to be considered in the contexts not only of the transmission of the documents which they represent, but also of the preservation and circulation of Selbold Cartularies or Kopialbucher, insofar as they are known or survive. Here we distinguish in red such historical records as the Selbold Cartulary Fragment(s) showcased here, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, one or more Selbold Kopialbuche (or Copialbuche) reported in German by various observers. We indicate one or other of those books known to have survived to the early modern or modern periods, but subsequently lost, or presumed to be lost, by a prefixed asterisk (*). Also recorded in some notices or copies thereof is a late-medieval [*]Liber privilegiorum et libertatum ecclesie Selboldensis (“Book of the Privileges and Rights of the Church of Selbold”), presumed to be lost.

Among the challenges, we might wonder to what extent one or other of those recorded [*]Selbolder Kopialbucher corresponds to this dismembered one. This post includes some detailed examinations of published editions of its texts and related texts. Why this detailed work is useful, and can yield strikingly significant results even for only a few leaves from a dispersed manuscript otherwise inaccessible, is revealed in the PostScript.

The subtitle for this post could be Manuscript Studies in a Time of Bibliographical ‘Lock-Down’. [Now see also the Addendum below.]

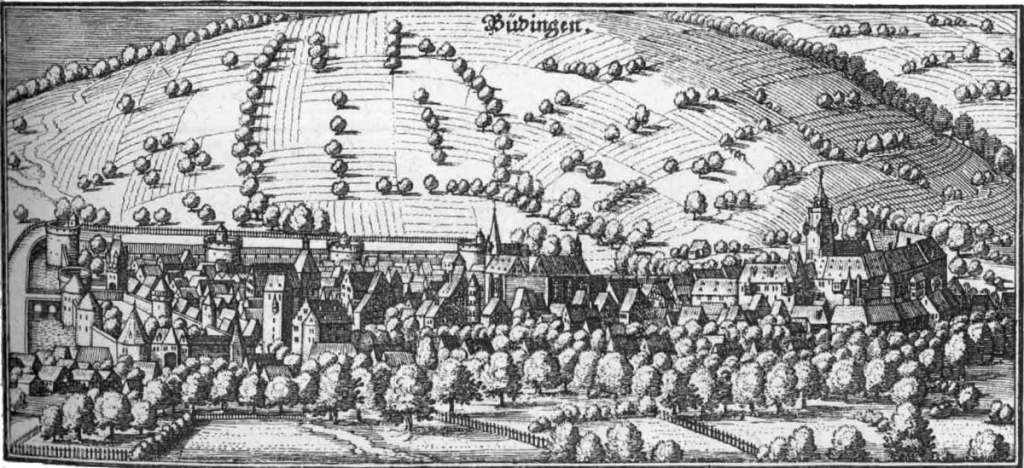

Selbold (or Langen-Selbold) in Hessen

Naumburg Cathedral, Donor Figure of Graf Dietmar (photograph of 1953). Deutsche Fotothek of the SLUB. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Selbold (modern Langenselbold) is a town in the Main-Kinzig district in Hessen. It is situated on the River Kinzig, 10 km east of Hanau. The oldest surviving documentary reference to the place dates to 1108 CE, when Kloster Selbold (likewise examined here) was founded by Graf Dietmar of Selbold, founder of the aristocratic dynasty of Selbold-Gelnhausen. The dynasty continued to have links with the monastery: “Die Gründerfamilie des Grafen Dietmar wurde über die Herren von Büdingen schließlich von den Isenburgern beerbt, auch hinsichtlich der Stiftsvogtei“.

Landmarks in the history of the monastery (surveyed in Schloss Langenselbold) include the papal permission for the foundation of a monastery for Augustinian canons at Selbold in 1108; its conversion to the Premonstratensian Order in 1139; its elevation to the stature of an abbey in 1343 under Abbot Johannes von Prèmontrè; its plundering by Grafs Heinrich and Johann von Isenburg in 1372; its plundering and devastation during the German Peasants’ Revolt in 1525; and the disbanding of the monastery in 1543, when the last abbot, Konrad Jäger, handed it over to Graf Anton von Isenburg-Büdingen (or Graf Anton I von Isenburg-Büdingen) (1501–1560).

The Premonstratensian monastery of Selbold was disbanded in 1543. Earlier forms of the place-name include Selbolt, by which name parts of the fragments refer to it. Perhaps needless to say, its documents and its cartularies (in one and another copy), report the names of numerous locations in its region as part and parcel of the historical record.

The Cartulary Fragment

The principal entries on the fragments reproduces the texts of privileges for the monastery, abbey, or Stift of Selbold in codex form. They transcribe documents whose dates of issue are said in accompanying modern notes to range from 1143 to the reign of Karl IV (1316–1378), King of Bohemia and Holy Roman Emperor (“HRI”), who reigned as HRI 1355–1378. A note upon its page dates the last document in the fragment, which breaks off abruptly before a dating clause, to 1363.

Prague, National Gallery, Anonymous, Votive Panel, in Tempera on Wood, of Jan Očko of Vlašim, before 1371. Detail: Charles IV. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Selbold cartularies, in one form or version or another, as well as the individual documents relating to the monastery of Selbold and its holdings, have been studied with some intensity. (See below.)

The fragment itself has several pencil notes which refer — in summary form — to editions by different scholars.

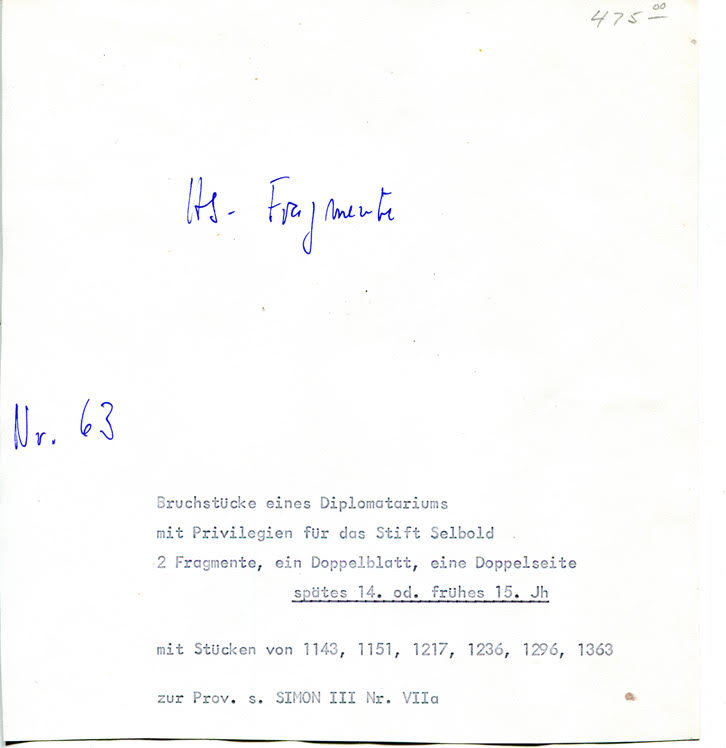

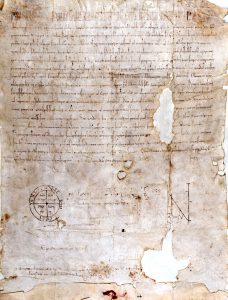

The Companion Note

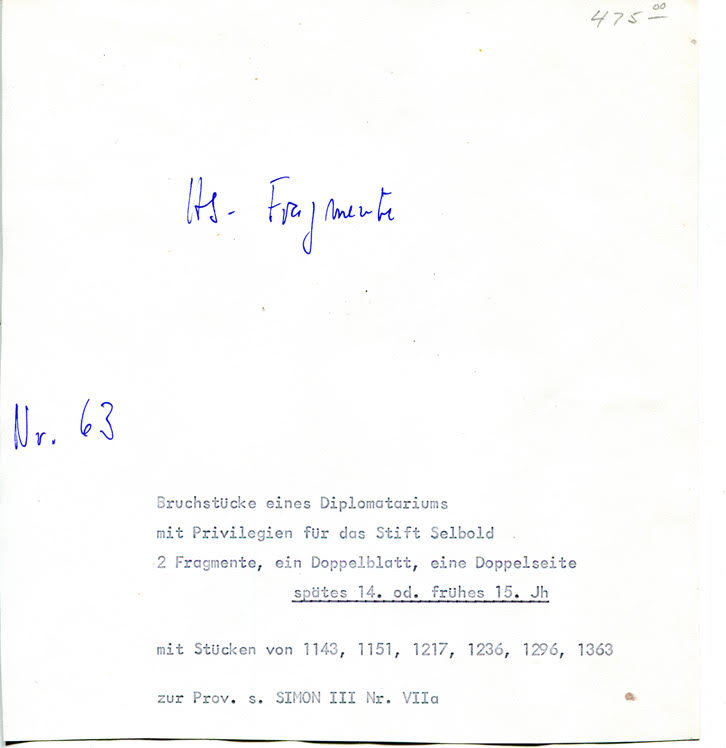

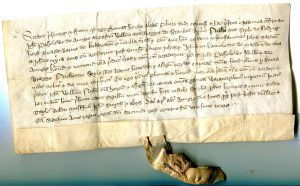

A “Companion Note” on a sheet of paper from the seller (shown here below) provides typescript information in 6 short lines in German about the fragments and their text. For example, it calls the item a set of Bruchstücke eines Diplomatarium mit Privilegien für das Stift Selbold (“Fragments of a Diplomatarium with Privileges for Stift Selbold”), observes that it dates from the spätes 14. od.[er] frühes 15. J[ahr]h[undert] (“the late 14th or early 15th century”), and declares that its texts or “pieces” (Stücken) come from the years “1143, 1151, 1217, 1236, 1296, 1363”.

The term Diplomatarium (“repository or archive for diplomata, or diplomas“) may mean that the unit undergoing dismemberment somehow carried that name, say as title, or was regarded as one. The format of the fragments establishes that its character as repository comprises copies of documents, not — at least in this portion — the documents themselves.

None of the references which I have found in other sources, such as editions, to a cartulary — or the like, with documents in book form — from Selbold uses this term. Might applying Diplomatarium to this fragment (or set of fragments) for sale constitute another sign of endeavoring to mask the true nature, title, and origin of the piecemeal offerings? On balance, in the light of available evidence, I am inclined to regard that supposition as very likely.

A pair of additions written in blue ink in a continental European hand label the leaves as “manuscript fragments” (Hs. Fragmente) and provide the number (Nr. 63) of some series or other. An addition in pencil in the upper right corner provides the price in an unspecified currency.

This leaf must have come from the seller’s German source for the item, directly or indirectly.

Note accompanying the Selbold Cartulary Fragments.

The Provenance or Implied Provenance

This Selbold Cartulary Fragment came to its current collection perhaps, at some removes, from Schloss Büdingen (or Schloss Büdingen) in Büdingen in Hessen. This edifice served as the Residence of the Grafschaft Isenburg.

According to the present collector’s recollection (in correspondence), the fragments are “presumably from the dregs of that collection, like the rest of what the seller had in the way of cheap German material”, and the “documentation” (on the sheet illustrated above) accompanying the sale was in “similar style and handwriting, as from the same source”. One might presume “that the Schloss collection was where a lot of the local material wound up when the institutions were secularized or dissolved”.

Schloss Büdingen seen from the Schlosspark. Photograph by Hadig 2004. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Isenburg, Ysenburg, Büdingen, Birstein

In examining the contents and the potential provenance of the Selbold Cartulary Fragment, it is useful to keep in mind the complex interconnections, subdivisions, and influences of the aristocratic House of Isenburg through the centuries, along with its documentary records and domains. Brief accounts in English or German survey such aspects for consideration in terms of regions and dynasties as:

For example, under the first heading (County of Isenburg), we learn that:

The House of Isenburg was an old aristocratic family of medieval Germany, named after the castle of Isenburg in Rhineland-Palatinate. Occasionally referred to as the House of Rommersdorf before the 12th century, the house originated in the Hessian comitatus of the Niederlahngau in the 10th century. It partitioned into the lines of Isenburg–Isenburg and Isenburg–Limburg–Covern in 1137, before partitioning again into smaller units, but by 1500 only the lines of Isenburg–Büdingen (in Upper Isenburg) and Lower Isenburg remained. In 1664 the Lower Isenburg branch died out. The Büdingen line continued to partition, and by the beginning of the 19th century the lines of Isenburg–Büdingen, Isenburg–Birstein, Isenburg–Meerholz and Isenburg–Wächtersbach existed. Today still exist the (Roman Catholic) princes of Isenburg (at Birstein), the (Lutheran) princes of Ysenburg (at Büdingen and Ronneburg) and the (Lutheran) counts of Ysenburg–Philippseich.

While here, we take note of the current locations for the Roman Catholic or Lutheran princes respectively of Isenburg at Birstein and of Ysenburg at Büdingen.

During the upheavals of the Reformation in Germany, different factions, interest-groups, and spheres of influence may have sought to gather earlier records and/or make copies of them for consultation and preservation, in the midst of dispersals or redistributions. Such efforts and activities appear to have affected the patterns of transmission of the cartulary records of Selbold, and to have partly interfered with the recognition of those patterns and their effects.

The Selbold Cartulary Fragment(s)

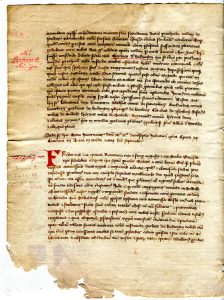

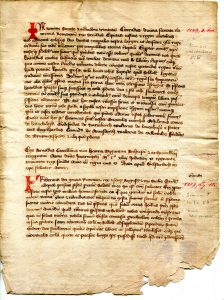

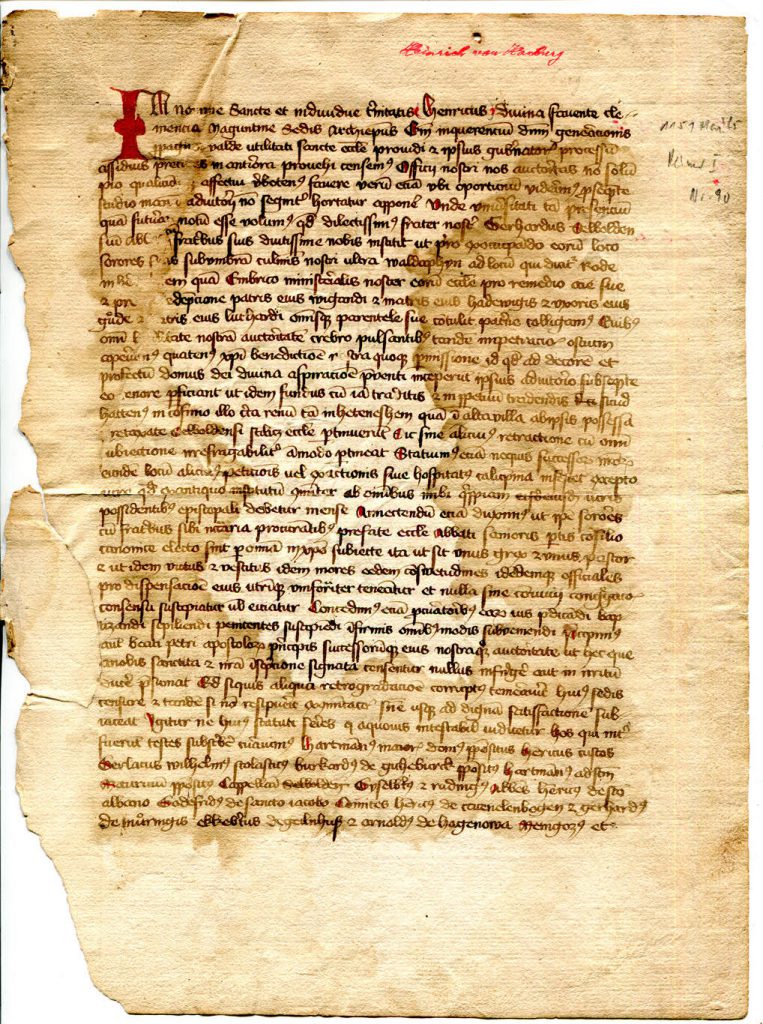

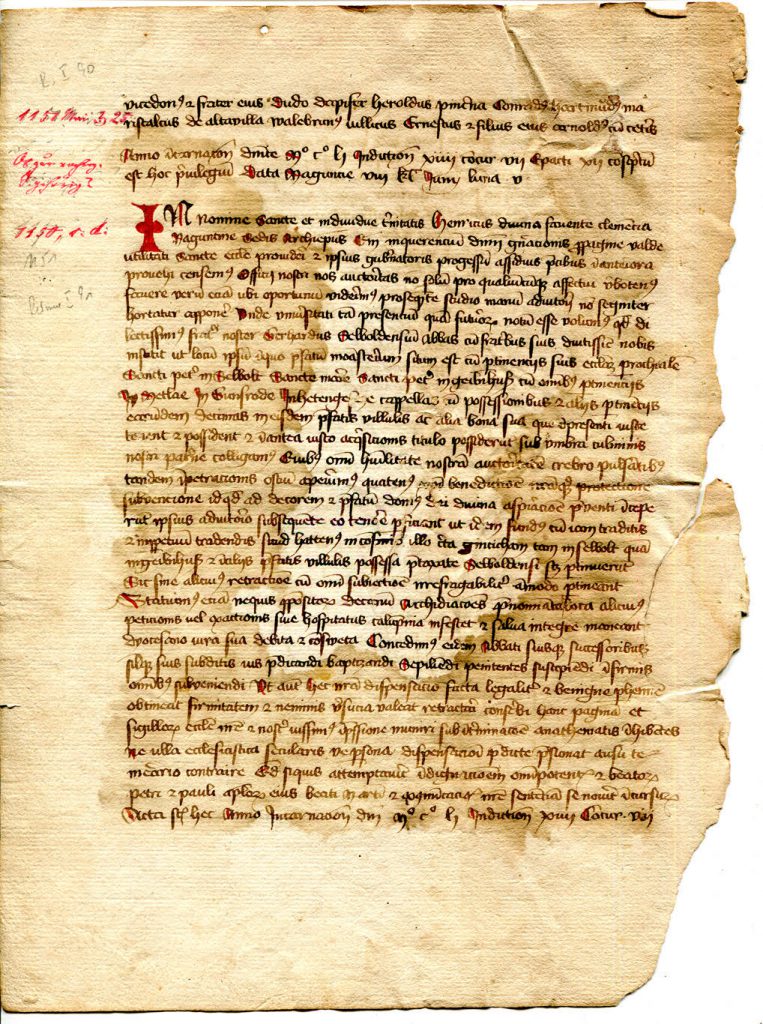

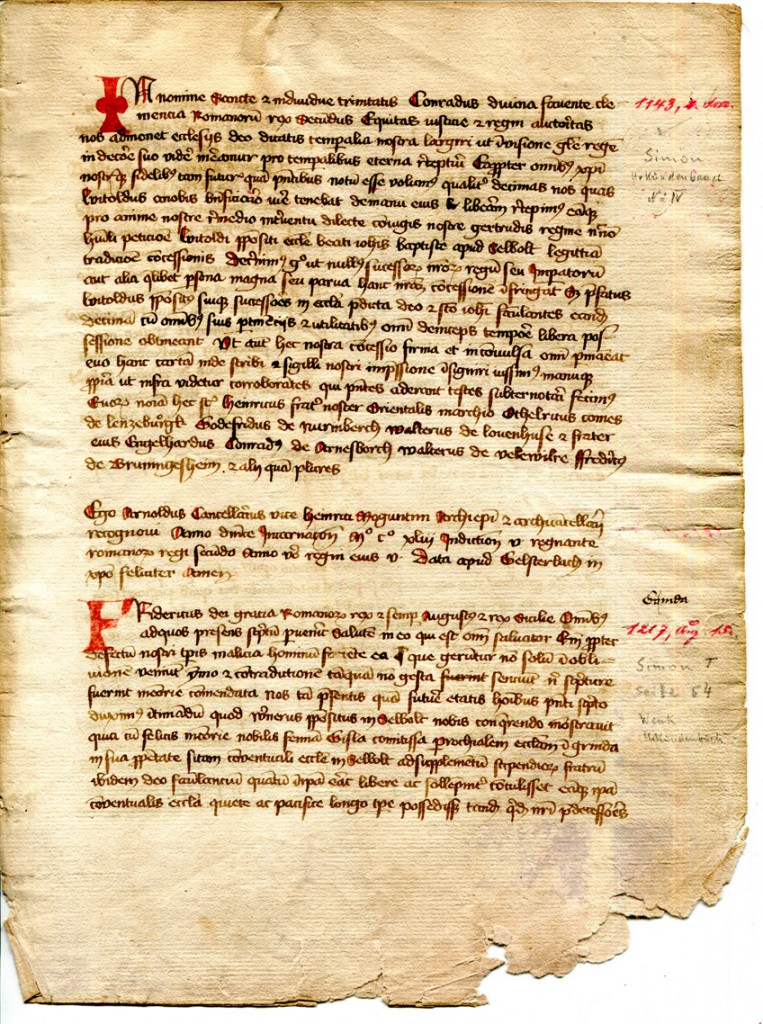

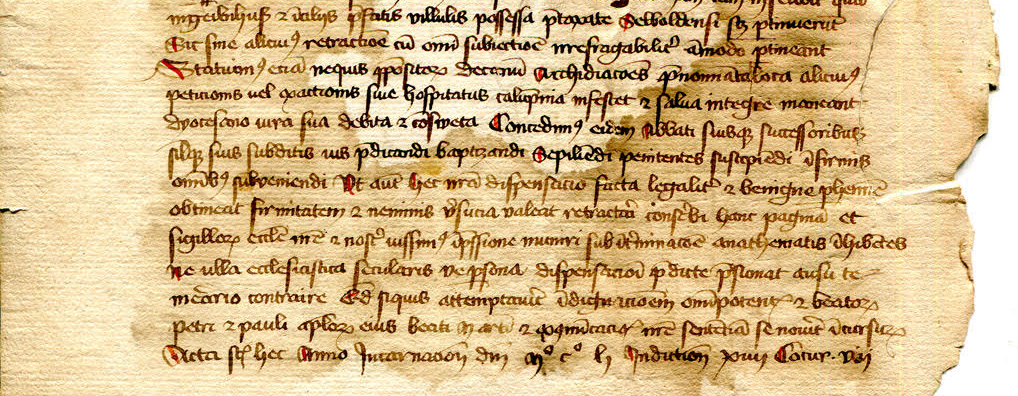

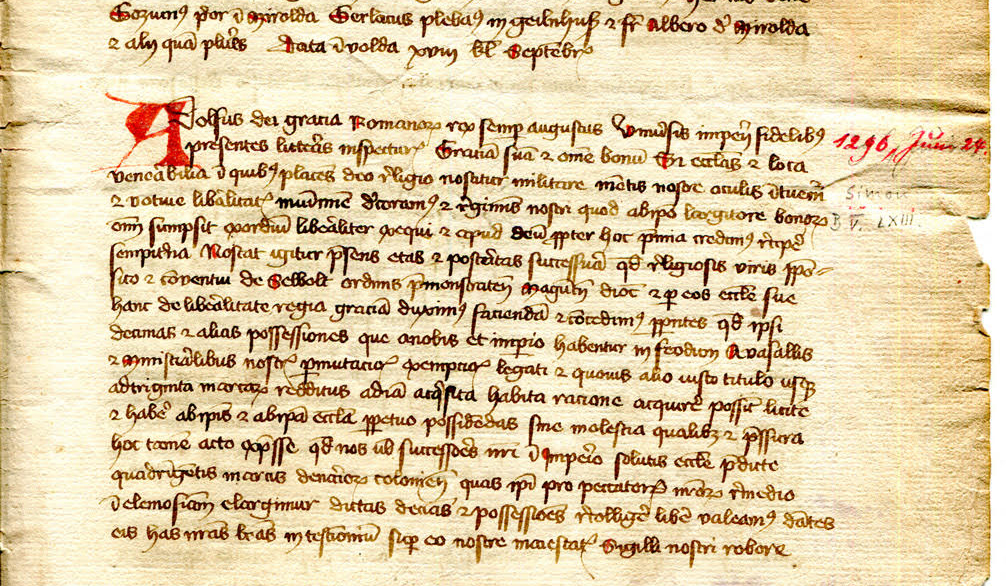

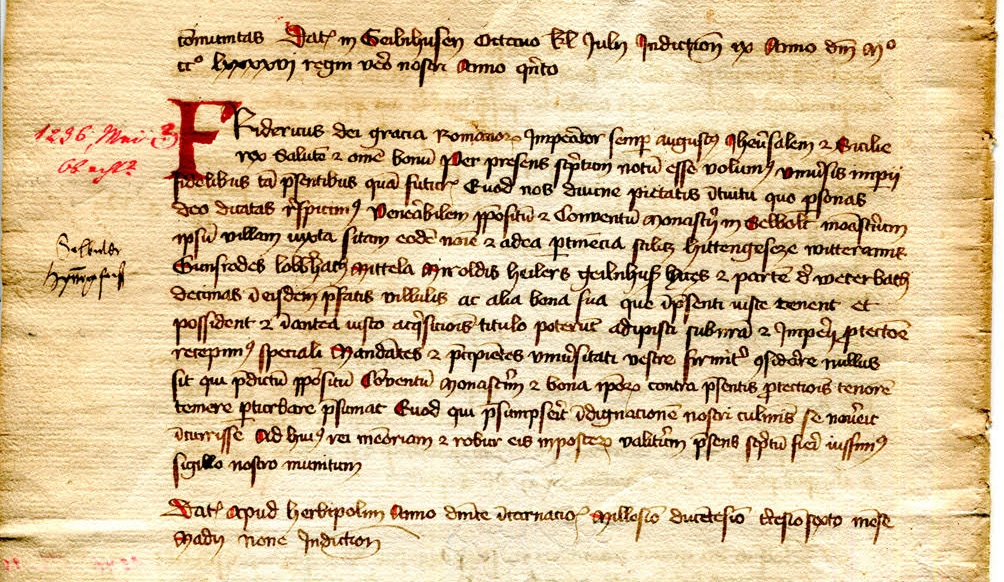

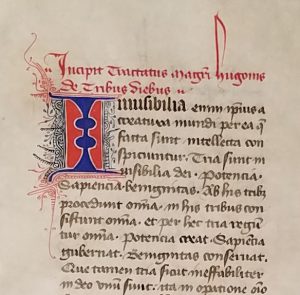

The leaves measure at the most circa 28.3 × 210 cm, with a written area of 20.6 × 15.5 cm. Laid out in single columns of 39 lines, the text is written in brown script by a single scribe, with embellishment in red pigment. The red pigment builds up the enlarged 2-line or 3-line initials of the copied documents, as well as the strokes which highlight and emphasize initials of phrases and names.

The Added Notations

Private Collection, Selbold Cartulary Fragment, Folio 2 verso.

Private Collection, Selbold Cartulary Fragment, Folio 2 recto.

In the margins and within some lines there stand some annotations. Several cursive annotations in dark brown ink appear to be late medieval or early modern (on the bifolium of folios “2” and “3” r–v). In the margins they signal, for example, some place-names in the text, as with Grinda (on folio “2”v) and both Selbolder and Hattenheim (on folio “3”v). One entry (folio “3”r) appears to be, or to include, a cypher of some sort.

The others, written in bright red ink and in pencil, are modern.

The entries in red ink stand mostly in the outer margins, but also underline a name of interest within the text of one document (folio “2” v). They note the dates of the documents — in arabic numerals for the year and the day, and with the word in German for the month — in a single line in the outer margin, usually opposite the first line of the document. On folio “1”, however, that form of entry ignores the opening of the document at the top of the recto, and stands instead opposite the first line of the continuation of its text onto the verso, where is found the dating clause. Entries in the same red pigment and script signal some personal names, as with Heinrich von Havelberg in the upper margin above the document of 15 March 1151 (folio “1” r) and Gerlacus de Büdingen! — with exclamation, plus wavy underline for the name within the text itself — within the first of 2 documents of 15 August 1217 (folio “2” v).

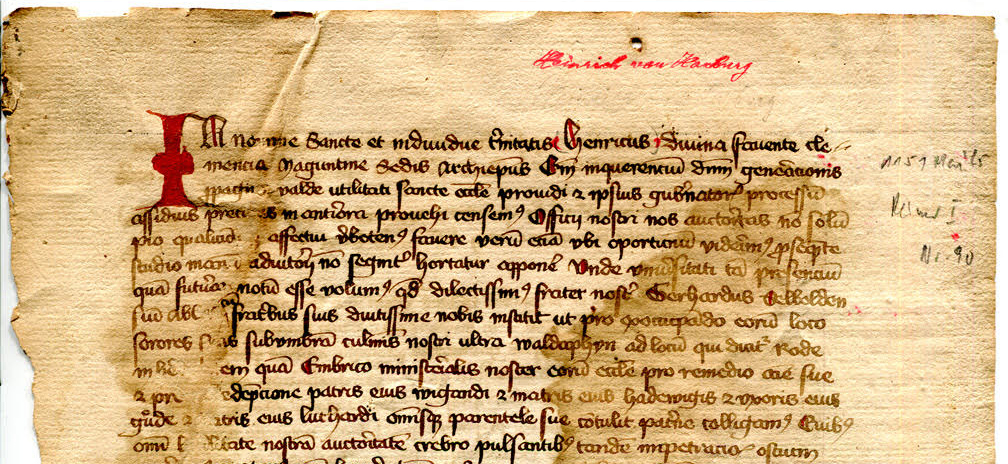

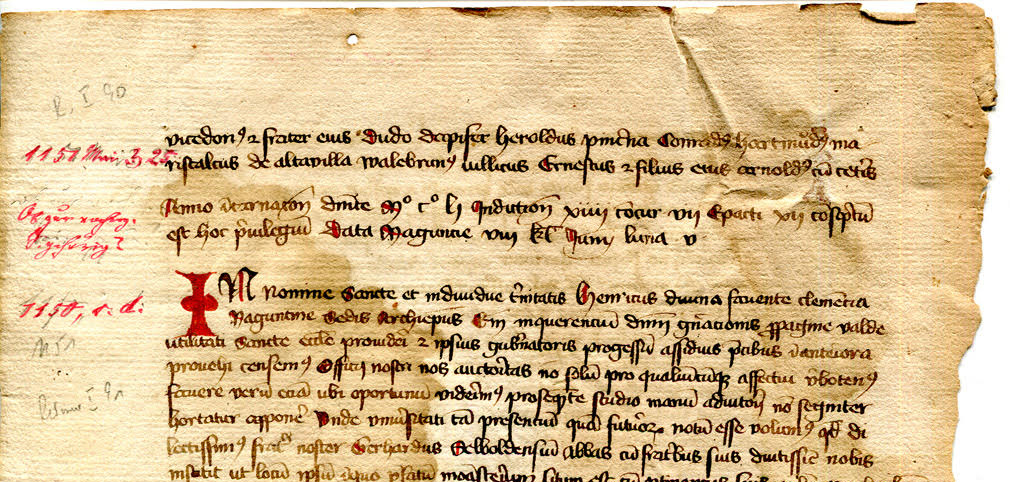

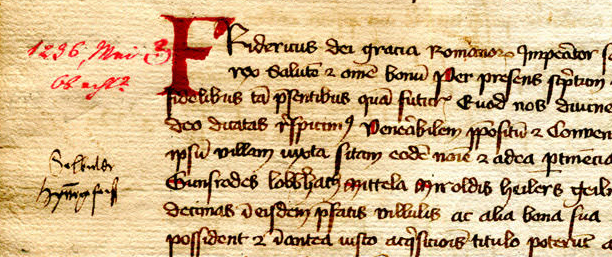

Selbold Cartulary Fragment, folio “1” recto upper portion. Text 1: Archbishop Heinrich I of Mainz, 25 May 1151.

Sometimes the red entry appears to get the date wrong, as might be the case with the second document (lowest on folio “1”v) and the last document (lowest on folio “3” v), for which latter the pencil entry lower down, rising diagonally to the right, is apparently correct. (Perhaps the result of new information in the progression of the research?) Likewise, the red note naming Heinrich von Havelberg in the upper margin of folio “1”r perhaps conflates Heinrich I, Archbishop of Mainz, named in the document, with his assistant in early years, the Premonstratensian Anselm of Havelberg (circa 1100 – 1158), who became Bishop of Havelberg and then Archbishop of Ravenna (1155–1158). The Premonstratensian Abbey of Selbold and its modern record-keepers may have had reason to favor records of that Premonstratensian notable.

The pencil entries note the dates of the documents and briefly or enigmatically cite some 19th-century editions in which the texts are transcribed. The citations report variously the name of the editor and/or edition (such as “Simon”, “Simon Urkundenbuch”, “Wenck”, etc.), a page (“Seite”) number, an assigned number (“Nr.”) for the document in an edition, or a combination of such elements — mainly intelligible for, or decipherable by, initiates in the fields of scholarly reference. To judge by the variable widths of strokes, alignments, and ductus of the pencil entries, the citations of editions appear to have been added in several stages, even with respect to individual documents, as the work of identifying the sources or resources advanced.

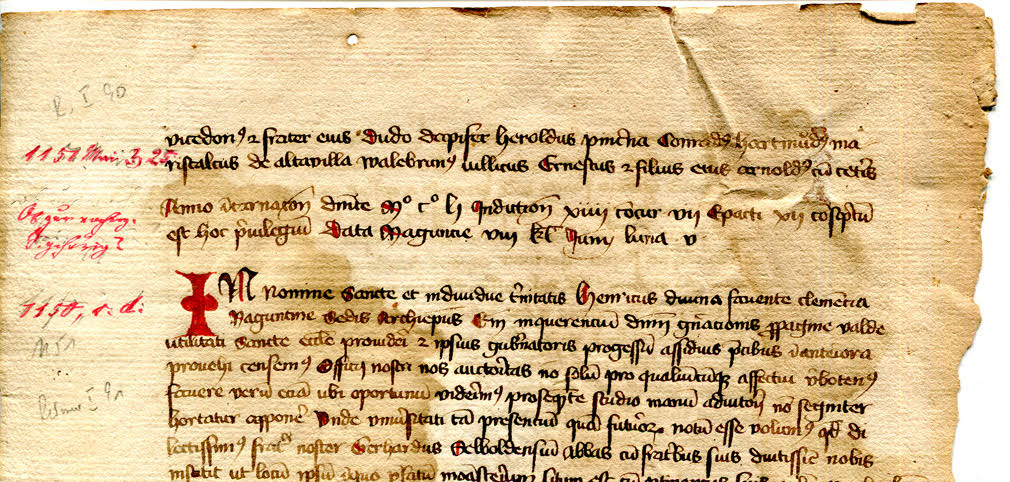

Selbold Cartulary Fragment, folio “3” recto lower portion.

The entries in red ink mainly retrace the relevant pencil entries of dates and names. The preceding pencil strokes remain partly visible outside the overdrawn contours of red ink. At the beginning of the document on folio “1” r, the pencil entry recording the date in the customary year–month–day order stands on its own, missed in the process of rubricating the selected modern notations. That rubricating stage perhaps aimed to enliven the manuscript, say for an owner or prospective buyer, after the research to identify the dates of its texts had come to completion.

The pencil notes and the writing of the names of editors or editions are so summary that deciphering them may have to “reverse engineer” the stages of acquaintance with those publications, by searching for likely publications, and then possibly confirming their accuracy, or searching further still. References to specific editions (insofar as they are identifiable) in the pencil notes establish termini post quem (“dates after which”) the pencil entries were made. See below. At the earliest, they would be late 19th century, and more likely later.

The seller’s typescript Companion Note (seen above) lists the dates (or presumed dates) of documents in a chronological order and refers to an entry number in “Simon” for information regarding the “Prov.”, presumably the “Provenance” of the fragments. Perhaps the focus of attention exhibited in the Companion Note provides some clues for the selection of these 3 leaves as a unit for sale.

The restraint in the Note avoiding a direct name or location for the Provenance may be significant. Perhaps covering tracks? It is also infuriating from the perspectives of manuscript studies.

The Condition

Private Collection, Selbold Cartulary Fragment, Folio 1 recto.

Private Collection, Selbold Cartulary Fragment, Folio 3 recto.

Different forms of damage demonstrate that the 2 portions of the fragment stood at different parts of the volume when it suffered water damage and mold. The single leaf (folio “1”) suffered water damage along both sides and across the bottom, with ‘ink lakes’ formed of runny ink leaving pronounced ‘tide lines’ at their ‘shores’. The 2 leaves of the bifolium (folios “2–3”) share a large darkened stain across the outer upper portion of each leaf, purplish stains from mold across the lower outer portion, and crumpled losses at the lower outer corner.

The water stains do not blur the marginal entries, although some of these entries occupy stained regions. Show-through from the red pigment entries in the margins affects the recto and verso of folio “2”. For example, the 2 red pigment entries in the outer margin of folio “2”v, respectively opposite line 1 and opposite line 7 of the document of 15 August 1217, are not matched by any such entries on folio “3”r.

Suffice it to say that the 2 segments of the fragment come from different parts of the volume, with some now-lost leaves intervening between the single leaf and the bifolium. The small rounded hole, perhaps a wormhole, in the upper margin of folio “1” but unshared by the bifolium may demonstrate that the span of lost leaves had some or considerable distance. The 3 leaves stand as disparate representatives of a former manuscript of a Selbold Cartulary, late-medieval in origin, written (at least partly) on paper, and dispersed for whatever reason(s).

The Leaves

The 1 + 2 leaves (singleton + bifolium) carry the transcriptions of their documents in 2 continuous series, but the 2 units are not continuous. A textual gap amounting to some leaves (number unknown) stands between them.

Always a skipped line stands between 1 document and the next. Usually the concluding clause for a given document stands as a separate “paragraph” or section, beginning its own line afresh at a distance of 1 skipped line below the body of the document proper. In one exception, at the top of folio “3” verso, the dating clause continues directly in the same line (v1).

Each document begins with an inset 2- or 3-line initial made in red pigment, in the form of a Roman or Gothic Capital. Written in ink, with an added stroke of red pigment, the next letter is an enlarged and usually Gothic Capital. Thus the opening of the document presents a brief dimuendo of 2 enhanced letters to the main text.

Preston Charters, Faces. Photograph Mildred Budny.

The script and layout make no distinctions in style of presentation between the different documents. They acquire a uniformity of appearance within the cartulary structure — their opening initials included.

(Examples in our blog of the differences in appearance between documents of different dates relating to a specific location or region appear in our posts on the “Preston Charters”, as with Preston Charters Continued. A profound case of a book-form manuscript, or “booklet”, written by a single scribe reproducing facsimile-like copies of a series of different texts, whose exemplars evidently differed markedly from each other in layout, structure, style, and dates of production, can be seen in the Liber Commonei within Saint Dunstan’s ‘Classbook’, closely examined here.)

Folio “1”

This leaf carries the transcripts of 2 documents, nearly complete. The first begins at the top of the recto, and continues to the first lines of the verso. The second fills the rest of the page, and comes close to completing its course at the end of the last line of the column, within the dating clause.

Recto

Private Collection, Selbold Cartulary Fragment, Folio 1 recto.

Verso

Private Collection, Selbold Cartulary Fragment, Folio 1 verso.

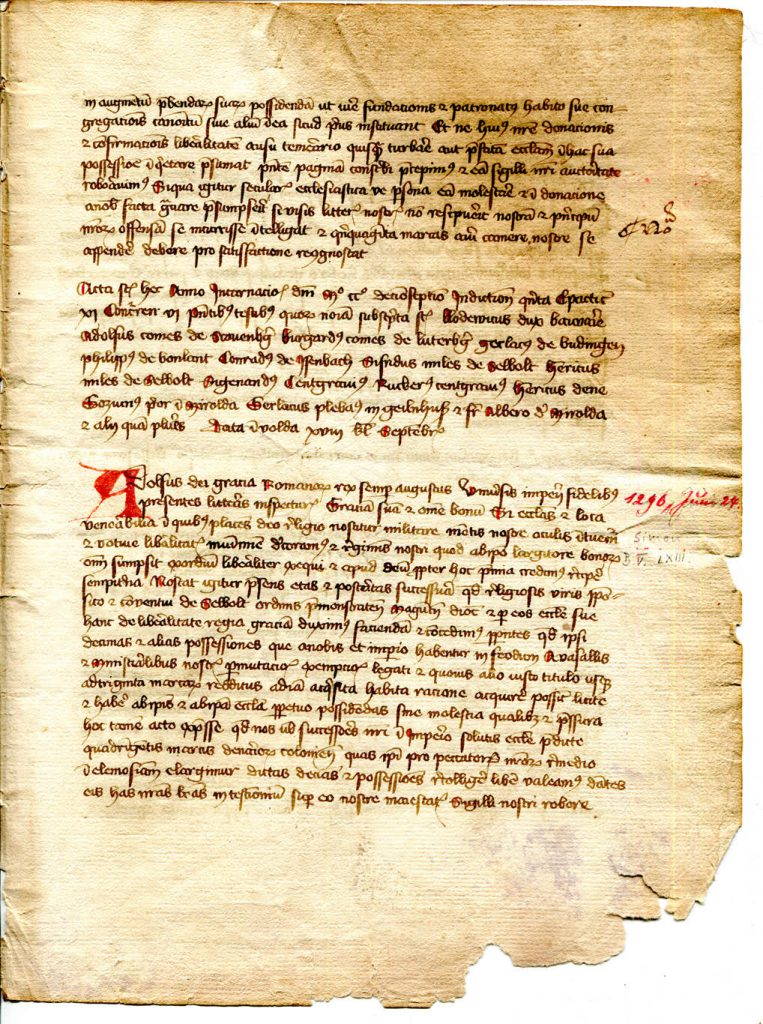

The Bifolium

The bifolium carries a continuous series of 6 texts, starting at the top of its first recto.

Folio “2”

Recto

Selbold Cartulary Fragment, Folio 2r.

Verso

Private Collection, Selbold Cartulary Fragment, Folio 2 verso.

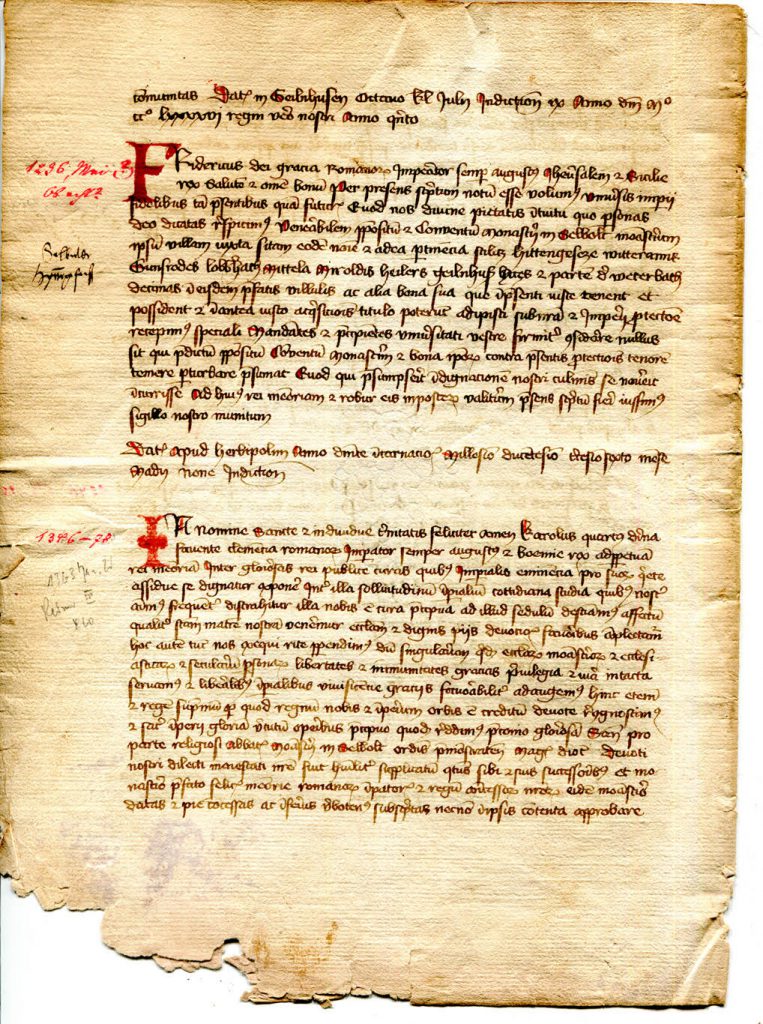

Folio “3”

Recto

Private Collection, Selbold Cartulary Fragment, Folio 3 recto.

Verso

Private Collection, Selbold Cartulary Fragment, Folio 3 verso.

The Watermark

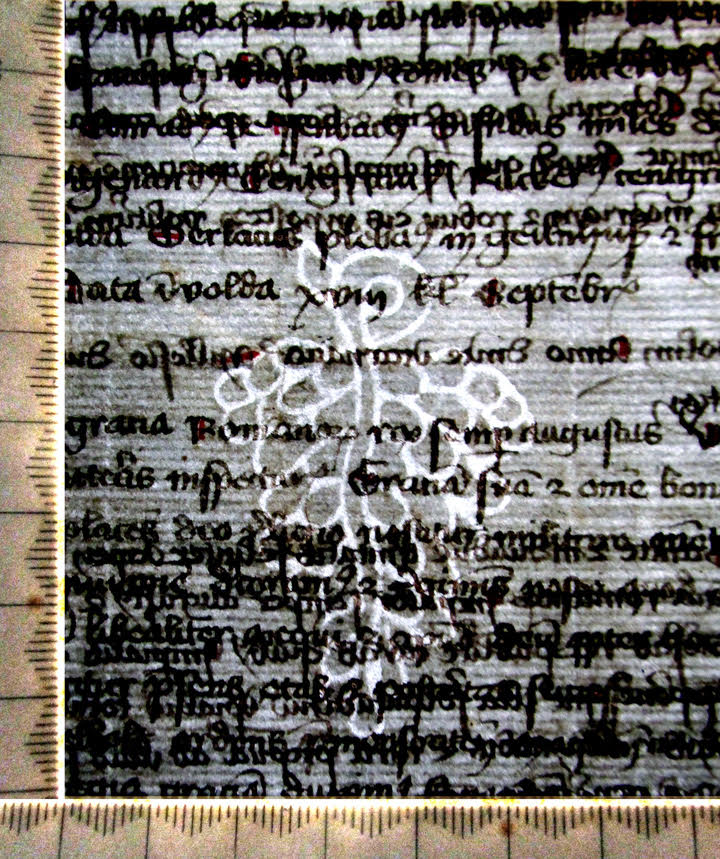

Folio “2” has a watermark, which stands upright on the leaf as employed for the text.

The watermark depicts a cluster of grapes. The bulbous grapes form rows to either side of the contours of the undulating stem. The stem forms a loop at the top, as it appears to pass “behind” itself in rising to one side (seen this way round, to the left) beyond the loop.

Grapes Watermark in a Selbold Cartulary Fragment.

The watermark with Scale and Back-Lighting

The stem of the cluster forms a loop at the top, as it appears to pass “behind” itself in rising to one side (seen this way round, to the left) beyond the loop. The grapes form rows to either side of the contours of the undulating stem.

Grapes Watermark in a Selbold Cartulary Fragment, with Back-Lighting and Scale.

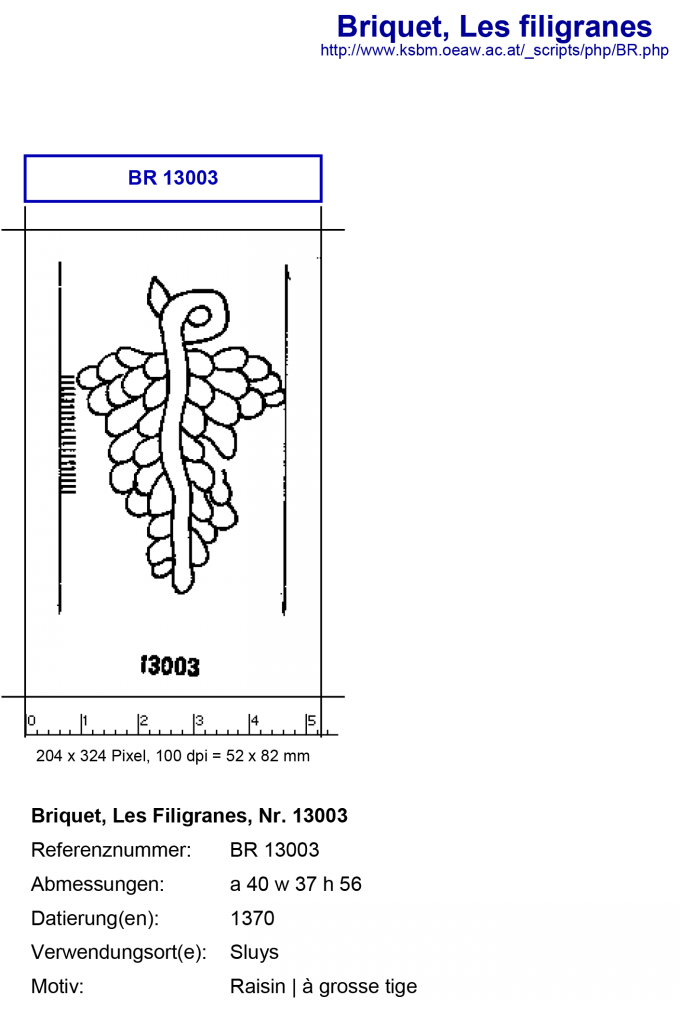

According to the standard of Briquet Online, which supplies a searchable version of the text and images in the monumental reference work by Charles Moïse Briquet (1839–1918) in his Dictionnaire historique des filigranes (Geneva, 4 volumes, 1907), this watermark belongs within Briquet’s class of Fruit, sub-group Rasin (“Grape”), variety à grosse tige (“with large stem”).

Briquet, Les Filigranes, Nr. 13003.

Among Briquet’s specimens, the watermark in the fragment comes closest to Number 13003, found in “München 1478” etc., with multiple sightings reported. That watermark was used in a wide range of dating contexts, from circa 1370 to 1509, and mostly in the 1420s to 1480s, so that here the watermark itself does not help especially with dating the manuscript.

According to Piccard Online, the mark belongs within the large subgroup of this Motifdarstellung (with 278 specimens):

Frucht – Traube – Ohne Beizeichen- Zweikonturiger Stiel – Mit Schlaufe am Stiel – Tropfenförmige Beeren

As yet, an exact match remains to be found among them. For example, in the image of the watermark, parts of the text obscure a clear counting of the number of grapes stand in each row flanking the stem.

Thus, so far, the assessment of the date of the manuscript must depend mainly upon its script and related features. Such may be the case with the assessments of the 14th- and/or 15th-century stated on the seller’s Companion Note and in an edition made apparently from this witness — unless, that is, these assessments had the benefit of other information contained within the book itself or its collection at the time.

The Companion Note

The typescript note supplied with the sale provides the date of “late 14th or early 15th century” (spätes 14. oder frühes 15. Jh.) At least, the medieval manuscript must postdate the dates of issue of the documents which it represents, whatever that span was once in full. According to this note, the documents in the fragment of a Diplomatorium presenting Priviligien für das Stift Selbold emanate from the years 1143, 1151, 1217, 1236, 1296, and 1363 — although a closer look at their texts gives a somewhat different view.

Within the fragment, the documents do not all align in chronological order, for example with a document of 1151 preceding one purportedly of 1150 (according to the date of the red ink notes on folio “1”), and with a document of 1236 standing in between one of 1296 and one of 1363 (on folio “3”).

The item number 63, if in a single series from that particular book, implies many fragments already. Who knows how high such a series went? The condition of the 3 leaves in this item make it clear that they had been selected, or gathered, from different parts of the book, so the series of items with numbers preceding 63 does not itself guarantee that they belonged to preceding parts in the volume, nor represented a consecutive order within it.

The typescript note provides oblique evidence — or its conjecture — for the Prov. of the fragment, by directing the reader to some other source:

zur Prov.[enz] siehe SIMON Nr. VIIa (“On the Provenance, see Simon, No. VIIa”).

Note accompanying the Selbold Cartulary Fragments.

“Simon Says”

On the quest of identifying the enigmatic reference “Zur Provenanz siehe Simon Nr. IV” on the Companion Note, where do we find “Simon Nr. IV”? The citations of “Simon” in pencil strategically on the leaves, along with some other names, offer guidance of some sort.

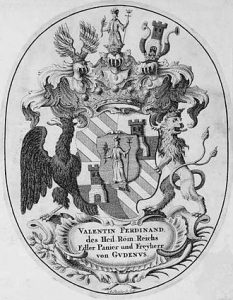

Elements of the history of the monastery of Selbold are reported by Gustav Simon in parts of Die Geschichte des reichsständischen Hauses Ysenburg und Büdingen (“The History of the Imperial House of Ysenburg and Büdingen”), published in 1865. Gustav Ludwig Georg Friedrich Simon (1811–1870) was a Lutheran evangelical pastor, deacon, and historian. A survey of that history involving Selbold and its connections with the dynasty occupies his Volume I, pages 28–52.

The references in the Companion Note to “Simon Nr. IV” and on the fragments themselves to “Simon” (plus title, page, or number) evidently pertain to his multi-volume work, notably its volumes 1 (Geschichte) and 3 (Urkundenbuch):

- Gustav Simon: Die Geschichte des reichsständischen Hauses Ysenburg und Büdingen

- Volume (Band) 1. Die Geschichte des Ysenburg-Büdingen’schen Landes (Frankfurt am Main: Brönner, 1865) via Google Books

- Volume 2. Die Ysenburg und Büdingen’sche Hausgeschichte (Frankfurt am Main: Brönner, 1865) via Google Books

- Volume 3. Das Ysenburg und Büdingen’sche Urkundenbuch (Frankfurt am Main: Brönner, 1865) via Google Books

The Texts

Editions of the documents represented in the Selbold Cartulary Fragments appear in various publications, by Simon and/or others in the 18th and 19th centuries — available for consultation freely online. The annotations in pencil on the fragments refer tersely to some of them, as with “Simon”, “Reimer”, and, presumably, “Wenck”.

Unpicking those references requires examining multiple editions of the texts on the fragments. The process of examination benefits from careful consideration of the manner of presentation in the editions, their notes, and their methods of citation — or not — of the witnesses consulted for edition.

Editions of Medieval and Early Modern Documentary Sources

Partly guided by the pencil annotations on the fragments (insofar those annotations are legible or can be deciphered), the identification of the texts and their editions has had to resort to online resources open while libraries are closed in Spring 2020.

For convenience, especially because of the links to their digitized versions, we refer to some editions and series of publications as listed in

- GenWiki

- WikiSource under Urkundenbücher und Regesten for German regions, thus:

Urkunden des Mittelalters und der Frühen Neuzeit / Medieval and Early Modern Documentary Sources

Hessen

Heinrich Reimer, Hessisches Urkundenbuch:

- Abtheilung 1 (“Erste Abtheilung”). Urkundenbuch der Deutschordensballei Hessen,

edited by Arthur Franz Wilhelm Wyss- Band 1: Von 1297 bis 1299. Publikationen aus den Königlichen Preußischen Staatsarchiven, 3 (Leipzig: S. Hirzel, 1879), digitized via UB Frankfurt/M., Internet Archive, Internet Archive = Google

- Band 2: Von 1300 bis 1359. Publikationen aus den Königlichen Preußischen Staatsarchiven, 19(Leipzig: S. Hirzel, 1884), via Google

- Band 3: Von 1360 bis 1399. Publikationen aus den Königlichen Preußischen Staatsarchiven, 78 (Leipzig: S. Hirzel, 1899), via UB Frankfurt, Internet Archive = Google, Internet Archive = Google, Internet Archive

- Abtheilung 2 (“Zweite Abtheilung”). Urkundenbuch zur Geschichte der Herren von Hanau und der ehemaligen Provinz Hanau,

edited by Heinrich Reimer

- Band 1: 767–1300. Publikationen aus den Königlichen Preuβischen Staatsarchiven, 48 (Leipzig: S. Hirzel, 1891), via MDZ, Internet Archive

- Band 2: 1301-1349. Publikationen aus den Königlichen Preuβischen Staatsarchiven, 51 (Leipzig: S. Hirzel, 1892), via UB Frankfurt/M, also GenWiki

- Band 3: 1350-1375. Publikationen aus den Königlichen Preuβischen Staatsarchiven, 60 (Leipzig: S. Hirzel, 1894), via “Digitalisat der Google Buchsuche (p2IOAAAAYAAJ), Digitalisat im Internet Archive“

- Band 4: 1376-1400. Publikationen aus den Königlichen Preuβischen Staatsarchiven, 69 (Leipzig: S. Hirzel, 1897), via “Digitalisat der Google Buchsuche (_9YqAAAAYAAJ), Digitalisat der Google Buchsuche (rmMOAAAAYAAJ), Digitalisat im Internet Archive“

- Band 1: 767–1300. Publikationen aus den Königlichen Preuβischen Staatsarchiven, 48 (Leipzig: S. Hirzel, 1891), via MDZ, Internet Archive

Nassau

- Karl Menzel and Wilhelm Sauer: W. Sauer, ed., Codex diplomaticus Nassoicus / Nassauisches Urkundenbuch. Die Urkunden des ehemals kurmainzischen Gebiets, einschlieβlich der Herrschaften Eppenstein, Königstein, und Falkenstein, der Niedergrafschaft Katzellenbogen und des kurpfälzischen Amts Caub, Band I (Wiesbaden: Julius Niedner, 3 Abtheilungen, 1885–1887)

- Band 1, Abtheilung 1 (1885), via UB Frankfurt/M., Internet Archive = Google-USA*, Internet Archive = Google-USA*

- Band 1, Abtheilung 2 (1886), via UB Frankfurt/M., Internet Archive = Google-USA*, Internet Archive = Google-USA*

- Band 1, Abtheilung 3 (1887), via UB Frankfurt/M., Internet Archive = Google-USA*

Other editions, too, come into play, partly because they are cited by the pencil annotations on the fragments, and partly because they sometimes reveal information about the witnesses — extant or lost — upon which their or others’ editions depend.

Johann Adam Kopp,

Tractatus Iuris Publici De insigni differentia inter S. R. J. Comites et Nobiles immediatos . . . (Strassburg, 2nd ed., 1725)

Stephanus-Alexander Würdtwein,

Diocesis Moguntina in archdiaconatus distincta . . . ex documentis authenticis (Mannheim: Typis Academicis, 1774)

Helfrich Bernhard Wenck, Hessisches Landesgeschichte, II,

Volume II: Urkundenbuch (Frankfurt am Mayn, 1797)

Gustav Simon, Die Geschichte des reichsständischen Hauses Ysenburg und Büdingen,

Volume III: Das Ysenburg und Büdingen’sche Urkungdenbuch (Frankfurt am Main: Brönner, 1865)

And also “Gudenus Codex Diplomaticus“? Still not sure about that one.

Variability of the Editions

Inconsistencies or variations among the editions in reporting which source texts served as the foundation for their edited texts, and in describing some of those sources, impedes the quest to discern the identities and interrelationships of those sources. In particular, our quest focuses upon known cartularies of Selbold (highlighted here in red), whether extant or lost (*).

The quest is further complicated by cursory citations of scholarly publications, both on the fragments themselves in pencil and in published accounts, including editions. For example, an editor’s reference (see below) to “Gudenus (Codex Diplomaticus)”, tout court, can be difficult to track, given, for example, multiple volumes or editions of a given publication (namely by Valentin Ferdinand von Gudenus), whose title might begin with that phrase, use those 2 words in some expanded form (which can vary from 1 work or edition to another), or pertain to more than one series, devoted to different centers of documentary corpora. With persistence and resourcefulness, however, paying attention to details of the different reports, it is possible to discern some contours among the gloom.

A bonus is that comparing the various editions, and the ways in which they report, or do not report, their source manuscripts or documents, makes some headway in lighting the path toward possibly identifying the late-medieval Selbold Cartulary Fragments among them.

The Documents As Represented

Here we number the documents consecutively as they appear on the fragments and highlight them in bold (“Texts 1–8“).

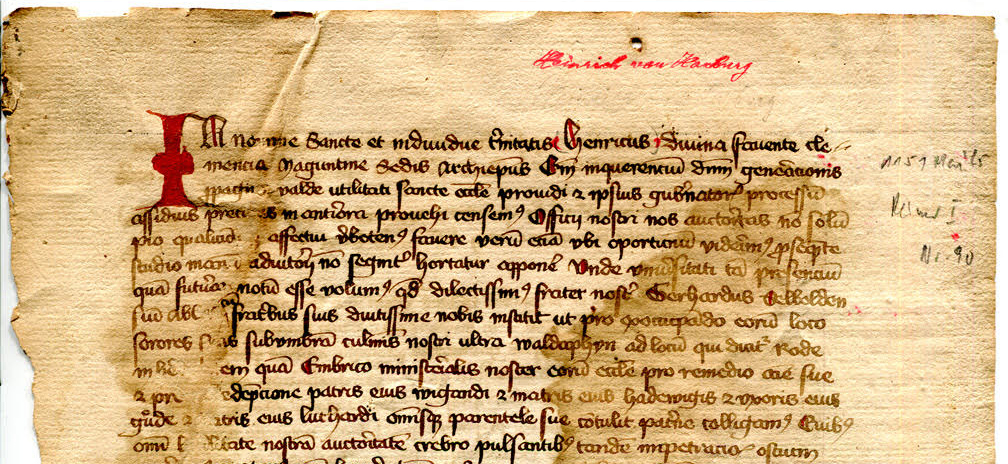

Leaf 1: Archbishop Heinrich I of Mainz

The single leaf carries the transcripts of 2 documents. The first begins at the top of the recto, and continues to the first 4 lines of the verso. The second fills the rest of the page, and comes close to completing its course at the end of the last line of the column. Both documents were issued in Mainz (Latin Mogontiacum) by Henry I or Heinrich I, Archbishop of Mainz (circa 1080 – 1153), archbishop from 1142 to 1153.

While libraries remain closed [Spring 2020], I have not yet seen:

Peter Acht, ed., Mainzer Urkundenbuch, II: Die Urkunden seit dem Tode Erzbischof Adalberts I. (1137) bis zum Tode Erzbischof Konrads (1200) (Darmstadt: Hessische Historische Kommission, 1968 and 1971).

Mainz Cathedral from SE before 1858. Photograph published by Hermann Emden (1858). Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Text 1. Archbishop Heinrich I of Mainz, at Mainz, 25 May 1151

Folio “1” r1 –v4

Selbold Cartulary Fragment folio “1” recto upper portion.

— In pencil on recto and verso: “Reimer I Nr. 90” / “R. I. 90”

Selbold Cartulary Fragment folio “1” verso upper portion.

Editions of the text include one “Reimer” as well as others.

= Heinrich Reimer, Hessisches Urkundenbuch, II. Urkundenbuch zur Geschichte der Herren von Hanau und der ehemaligen Provinz Hanau, 1: 767–1300 (Leipzig: S. Hirzel, 1891), No. 90 (pp. 62–64).

In which “Erzbischoff Heinrich von Mainz bewilligt dem Kloster Selbold die stiftung eines von abte abhängigen frauenklosters zu Rode bei Walluf.”

Edited from 1 witness: “Abschrift im Selbolder kopialbuche zu Birstein (B)“

Also (for example):

= Karl Menzel and Wilhelm Sauer, eds., Codex diplomaticus Nassoicus: Die Urkunden des ehemals Kurmainzischen Gebiets, einschliesslich der Herrschaften Eppenstein, Königstein und Falkenstein; der Niedergrafschaft Katzenelbogen des Kurpfälzischen Amts Caub (Wiesbaden: J. Niedner, 1885), Volume I (Wiesbaden, 1885), No. 228 (pp. 166–167)

[Repeated in Wilhelm Sauer and Karl Menzel, Die Urkunden des ehemals Kurmainzischen Gebiets, ein schliesslich der Herrschaften Eppenstein, Königstein und Falkenstein: der Niedergraftschaft Katzenelnbogen und des kurpfälzischen Amts Caub, Volume 1, Part 1 (Wiesbaden: J. Niedner, 1886), No. 228 (pp. 166–167).]

In which “Erzbischoff Heinrich I. von Mainz nimmt das von dem Kloster Selbold bei Rode gegründete Frauenkloster in seinen Schutz bestatigt demselben den Besitz der von Embricho von Steinheim geschenkten Güter und der bisher den Kloster Selbold gehörigen Güter zu Hattenheim und Eltville und gestattet der Klostergeistlichen die Ausübung von Pfarrechten” (p. 166).

This edition notes that the document was also printed by “Wenck, Hess. L.–G. IIb, S. 101.” That is:

Text 2. Variant of the Same:

Archbishop Heinrich I of Mainz, [at Mainz, 25 May] 1151, Incomplete

Folio “1” v5–34

Selbold Cartulary Fragment, Folio “1” verso upper portion.

— In pencil: “Reimer[?] I 91[?]”

= Heinrich Reimer, Hessisches Urkundenbuch, II. Urkundenbuch zur Geschichte der Herren von Hanau und der ehemaligen Provinz Hanau, 1: 767–1300 (Leipzig: S. Hirzel, 1891). No. 91 (pp. 64–65), with comments as to how and why the document is a forgery.

In which “Erzbischof Heinrich von Mainz nimmt das Kloster Selbold mit seinen besitzungen in seinen schutz”.

“Abschrift im Selbolder kopialbuche zu Birstein (B) . . . Die urkunde ist gefälscht auf grunde . . . ” (p. 65).

At the end of the page, the text in the fragment ends abruptly within the dating clause, and before the statement of location, month, and day. According to the printed edition (and to the comparable conclusion of Text 1 higher on the page), that clause would have concluded in a line or two of script on the next page (now lost):

Anno incarnationis dominice MCLI., indictione XIIII., concurrente VII.,

[ / epacta XII. conscriptum est hoc priviligium. Datum Moguntie VIII. calend. Juni, luna V.]

Selbold Cartulary Fragment folio “1” verso lower portion.

Who knows why the partition of this Selbold Cartulary Fragment into the 3 leaves alone chose to truncate the text? We might imagine that the couple of lines or so “left over” from this text at the top of the next recto were deemed insufficient as a claim when the next document(s) of whatever contents might exert a claim of their own by virtue of beginning (presumably) with a prominent initial and new section, with a view for some other claimant as buyer.

Folios “2–3”: Kings and Holy Roman Emperors

Charter (2nd copy) of King Conrad III of Germany for Stift Ranshofen, issued between June and September 1142. München, Bayerisches Hauptstaatsarchiv, Kaiserselekt 467. Image Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The bifolium carries 5 more texts, plus the first part of a 6th, which breaks off abruptly mid-phrase at the end of the last line on folio “3”. All 6 documents were issued by secular rulers, including some Holy Roman Emperors (“HRI”).

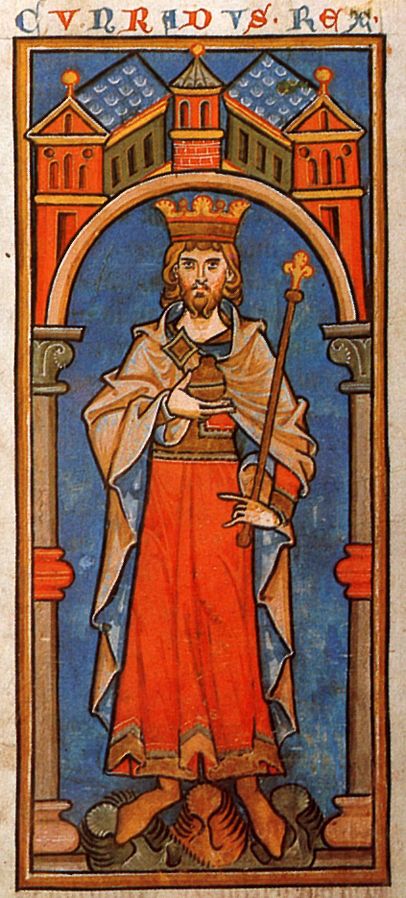

- Conrad III (1093 or 1094 – 1152), Duke of Franconia (1116–1120), Anti-king (1127–1135) of his predecessor King Lothair III, and King in the Holy Roman Empire (1138–1152)

- Frederick II (1194–1250), King of Sicily from 1198, King of Germany from 1212, King of Italy and Holy Roman Emperor from 1220, and King of Jerusalem from 1225

- Adolf, King of Germany (circa 1255 – 1298), Count of Nassau from circa 1276 and King of Germany (King of the Romans) from 1292 until his deposition in 1298

- Karl IV (1316–1378), King of Bohemia and Holy Roman Emperor from 1355–78

There are 1 document apiece for Conrad III, King Adolf, and Karl IV, and 3 for Frederick II.

The editors and editions of several of these texts prove revealing as to the nature of their manuscript witnesses.

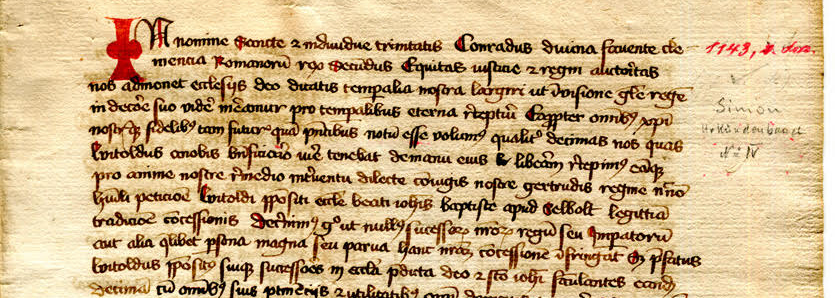

Text 3. Conrad III in 1143 (Regnal Year 5) at Gelsterbach (Kelsterbach)

Folio “2” r 1–23

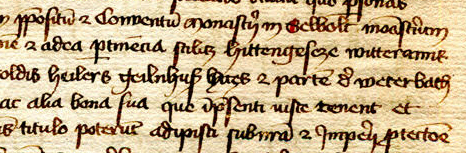

Selbold Cartulary Fragment, Folio “2” recto upper portion.

— in pencil: “Simon / Urkundenbuch / Nr IV”

= Gustav Simon, Die Geschichte des reichsständischen Hauses Ysenburg und Büdingen,

Volume III: Das Ysenburg und Büdingen’sche Urkungdenbuch (Frankfurt am Main: Brönner, 1865), Volume III, No. IV (pages 8–9)

In which “Der Römische König Konrad III. schenkt dem Kloster zu Selbold einen Zehnten, welchen der Propst Liutold daselbst bisher als Rechslehn besaβ, also freies Eigenthum” (page 8).

Edited from 1 documentary witness: “Aus dem Originale im Archiv zu Birstein” (that is, the parchment document, but missing its original seal)

Miniature of Conrad III of Germany from Chronica Regia Coloniensis (Cologne Kings’ Chronicle; Cologne; ca. 1240). Brussels, Bibliothèque Royale, Ms. 467, fol. 64v. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

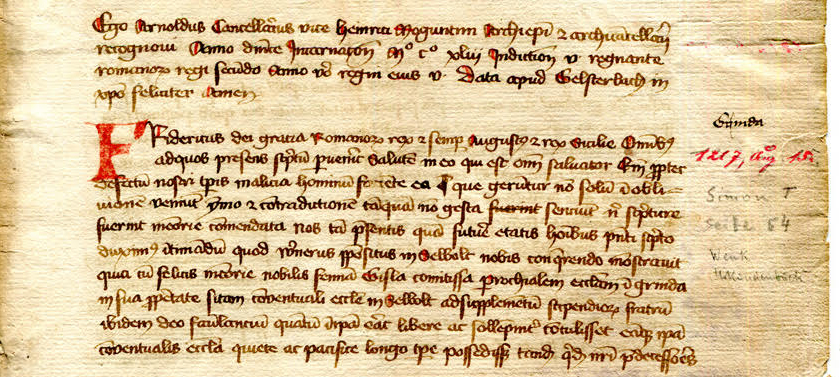

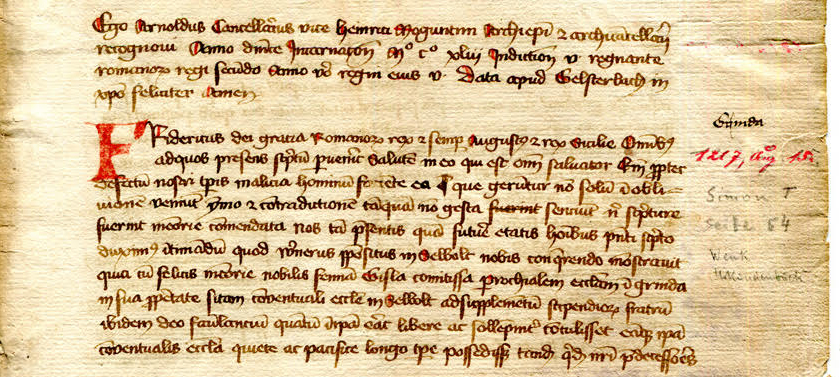

Texts 4–5. Frederick II on 15 August 1217 at Volda (Fulda)

Text 4. Frederick II, 15 August 1217 at Volda (Fulda)

Folio “2”r24–”2″v19

Selbold Cartulary Fragment, Folio “2” recto lower portion.

— in pencil: “Simon T / Seite 54 / Wen[c]k[?] / Urkundenbuch” (with the T more-or-less in the same line as Simon, but in firmer, darker strokes)

“Page 54” of “Simon” or “Simon T”(?) presumably refers to:

Gustav Simon, Die Geschichte des reichsständischen Hauses Ysenburg und Büdingen (Frankfurt am Main: Brönner, 1865), pp. 54–55 on the history of Grindau and Frederick II’s decision (Urtheil) about it in 1217. (See also next Text.)

= Stephanus-Alexander Würdtwein, Diocesis Moguntina in archdiaconatus distincta . . . (Mannheim: Typis Academicis, 1774), No. CXIII (pp. 162–163)

In which “Ecclesia Gr. [= Grinda] donatur Selboldensibus”

Text 5. Variant of the Same

Folio “2”r–v

Selbold Cartulary Fragment, Folio “2” recto lower portion.

— in pencil: “Simon T / Seite 54 / Wie vor [‘as above’]” (with the T more-or-less in the same line as Simon, but in a firmer, darker stroke, perhaps unrelated)

Variant of the same (See Text 4), ending on the recto with contulemus perpetuo and continuing on the verso with in augmentum . . .

= Helfrich Bernhard Wenck, Hessisches Landesgeschichte, II, Volume II: Urkundenbuch (Frankfurt am Mayn, 1797), No. XCVII**, pages 135–136, including observations on the doubled copies of the document, with some differences in their wording.

Note ** (p. 135):

Es ist diese Urkunde in einer doppelten, den Worten nach meist verschiednen, Form ausgefertigt worden, woron die gegenwärtige de letztere scheint, weis sie in einigen Stücken etwas umständlicher und bestimmter ist, als die andre. Vermuthlich war eben diese Berichtigung die Ursache der doppelten Ausfertigung.

Note * (p. 136):

In gedachtem ersten Auffaβ dieser Urkunde heist es nach den Engangeformeln: In de est, quod ecclesie congregationis canonice in Selbold [ . . . ] sive alium, sicut prius, instituant, worauf die Endformeln und die nemlichen Zeugen folgen.

(vg. Simon, Geschichte des reichständischen Hauses Ysenburg und Büdingen I., S. 55)”.

Tomb of Frederick II, Palermo Cathedral. Photograph © José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro 2015 via Creative Commons.

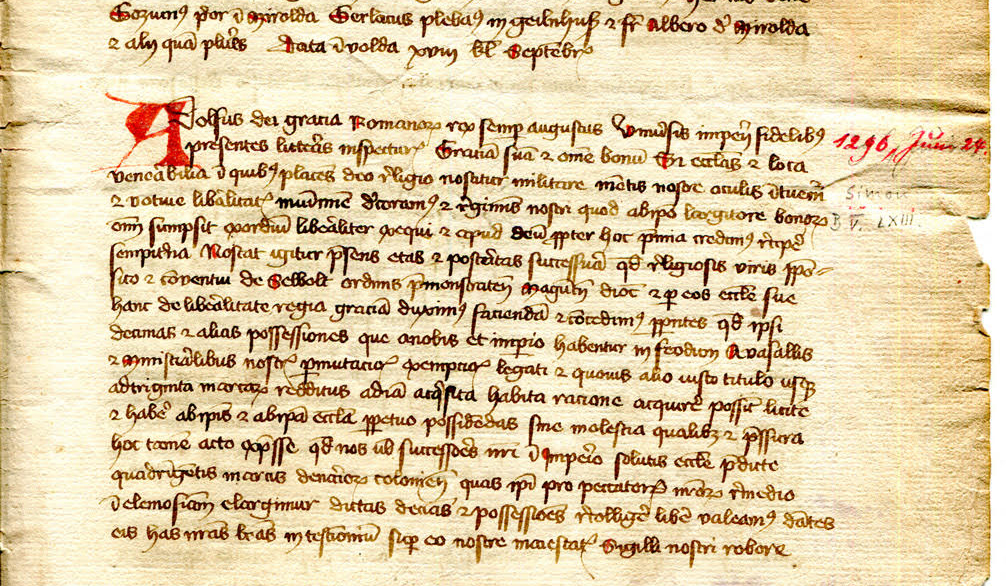

Text 6. King Adolf, 15 July 1296 at Geilnhusen (Gelnhausen)

Folio “3” r–v

Selbold Cartulary Fragment folio “3” recto lower portion.

= Gustav Simon, Die Geschichte des reichsständischen Hauses Ysenburg und Büdingen,

Volume III: Das Ysenburg und Büdingen’sche Urkungdenbuch (Frankfurt am Main: Brönner, 1865), No. LXVIII (pages 69–70)

In which “der römische König Adolf gestattet dem Kloster Selbold, reichtslehenbare Güter bis zum Betrage von 20 Wart jährligher Einfünfte durch Kauf, Tausch, Schenkung oder auf andere rechtliche Weise zu erwerben”.

Edited “Aus dem Selbolder Cop[ial].-Buche“

= Reimer, Urkundenbuch (1891), No. 759 (pp. 553–554)

In which “König Adolf erlaubt dem kloster Selbold, zehnten und andere reichslehen bis zum betrage von 30 mark einkünften zu erwerben”.

Witnesses, including a criticism of Simon’s “faulty” edition and the citation of 2 more editions, from a 15th-century copy and from an unspecified witness:

[1] Selbolder kopialbuch zu Birstein. Hiernach gedruckt: Simon III 69 (fehlerhaft).

[2] Ferner nach einer abschrift des 15. jahrh. zu Büdingen gedruckt von Dr. Schenk zu Schweinsberg im Archiv für hess. Geschichte XIV 248.

[3] Vergl. Kopp Iuris Germ. privati spec. II. de testamentis Germanorum 199.

= “W. Crecelius in Siberfeld” [Gustav Schenk zu Schweinsberg], “Zur Geschichte des Hauses Ysenburg”, in Archiv für hessische Geschichte und Altertumskunde, 14:1 (1875), pp. 245–355, at pp. 247–248, citing a 15th-century Abschrift in the “old” Archive at Büdingen and its variants from Simon’s edition from the Selbold Copialbuch, but without specifying whether that “copy” constituted a document or a codex.

= Johann Adam Kopp, Iuris germanici privati specimen secundum De testamentis Germanorum judicialibus et sub Dio condita vulgò Ungehabt und Ungestabt . . . (Frankfurt am Main: Johann Friedrick Fleischer, 1736), No. 6 (pp. 199–200). Kaisers Adolffi Privilegium.

In which “Das das Kloster Selbold auch Reichs Lehensbahre Güther von denen Vasallen und Ministerialibus, durch Vermächtnüβe und sonsten an sich bringen möge”.

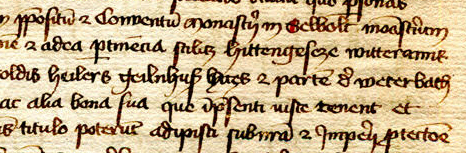

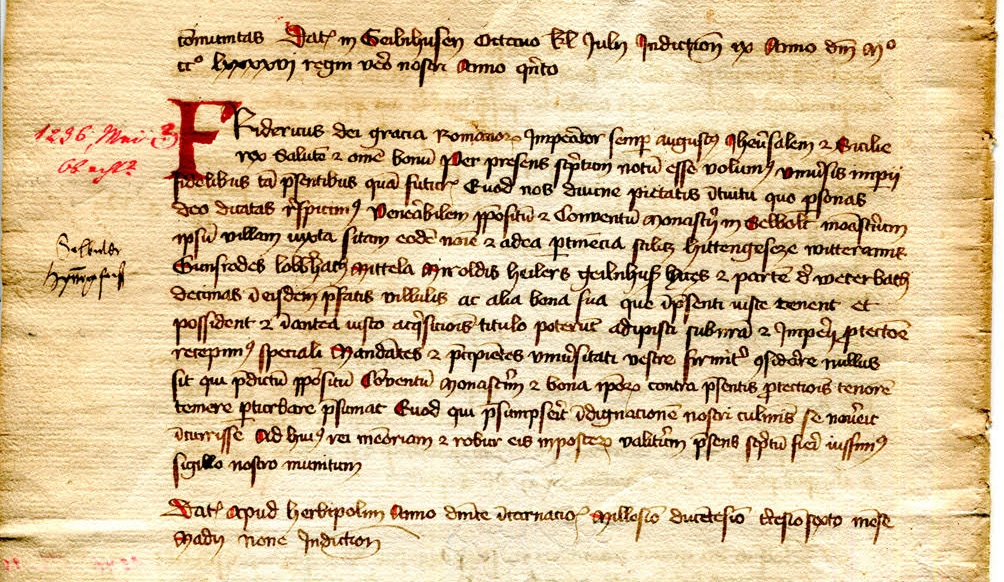

Text 7. Frederick II, May 1236 at Herbipolim (Würzburg)

Folio “3” v3–17

— “123[?]6, Mai 3” as stated in red ink at the left

Selbold Cartulary Fragment folio “3” verso upper portion. Text 7: Frederick II, May 1236.

= Simon III (Das Ysenburg und Büdingen’sche Urkungdenbuch (1865), No. VIIa (page 13)

In which “Kaiser Friedrich II. nimmt das Kloster Selbolt uebst den Besitzungen desselben in seinen Schutz”.

The single witness employed for Simon’s edition is said to be a copy dating from the “14th or beginning of the 15h century” in a specific Private Collection:

1 witness: “Nach einer Abschrift aus dem 14. oder dem Anfange des 15. Jahrhunderts im Privatbesizte des Fürsten Bruno zu Ysenburg [highlights added].

Nicht ganz vollständig abgedrucht bei Wenck, II.”

That is:

= Helfrich Bernhard Wenck, Hessische Landesgeschichte, II : Urkundenbuch (1797), no. CXVIII (pp. 153–154).

In which “K. Friedrich II. bestätigt dem Kloster Selbold seine Besitzungen, im Mai 1236”.

On Wenck’s incomplete edition (according to Simon), see below.

Observations on Simon’s Witness for Text 7: In the Collection of Prince Bruno of Ysenburg–Büdingen

We pause the course of scrutiny of editions of the texts contained within the Selbold Cartulary Fragment and of editions of its Text 7 in order to consider the character of Simon’s Witness for this text and its position among witnesses to the transmission of Selbold Cartularies as a genre.

Private Collection, Selbold Cartulary Fragment, Folio 3 verso.

The single witness which Simon’s edition (1865), No. VIIa (page 13), employed for the text issued by Fredrick II at Würzburg in May 123 was “a copy (Abschrift) from the 14th or beginning of the 15th century in the Private Collection of Fürst Bruno zu Ysenburg“.

That owner would be none other than Bruno, Prince of Ysenburg and Büdingen (1837–1906). He held the title of His Serene Highness, The Prince of Ysenburg and Büdingen, from 16 February 1861 to 26 January 1906. This position pertained to the House of Ysenburg-Büdingen, a Cadet branch of the House of Ysenburg .

It remains unspecified what form and format was taken by the Abschrift. Perhaps the deployed witness — provided it was a manuscript rather than a document — is this very fragment of a Selbold Cartulary (shown at the right), whose text corresponds fully with Simon’s edition, albeit with his silently expanded abbreviations and supplied punctuation.

Putting the clues together, the reference in the Companion Note (see above) to this edition by “Simon III Nr. VIIa” for the “Prov.” of the “Hs.” (or manuscript) fragment might imply confirmation of the ownership of this very cartulary at Schloss Büdingen, as the present owner of the fragment surmised (see above). If so, the datings cited by Simon (Abschrift aus dem 14. oder dem Anfange des 15. Jahrhunderts) and by the Companion Note in typescript (spätes 14. oder frühes 15. Jahrhundert) would approximately concur in their assessments of the same manuscript, which could derive from some indicator(s) inscribed within it.

Schloss_Büdingen. Photograph by Sven Teschke (2006), via Creative Commons.

An Observation about Deciphering the Text

It is worth considering Simon’s notice that this text had “not been entirely completely printed by Wenck” (Nicht ganz vollständig abgedrucht bei Wenck, II). How, exactly?

In contrast to Simon’s, that edition — Wenck (1797), no. CXVIII (pp. 153–154) — introduced an elipsis:

“Geilnhusen, . . . & partem de Weterbach”.

Apparently for this reason alone Simon declared that edition “not entirely complete”. He deciphered the intervening portion as “Hectzs”.

Examination of the passage in the Selbold Cartulary Fragment itself allows for some sympathy for Wenck’s decision to give up on such a compacted clump of letters. (See the center of the 3rd line in the image below.) Such observations might permit us to wonder if Wenck and Simon were looking at this same witness.

Selbold Cartulary Fragment folio “3” verso upper portion. Text 7: Frederick II, May 1236.

If not, this witness would have had to resemble closely a source very much like it, fudging the spelling from an exemplar difficult to decipher in precisely this place in an otherwise mostly legible text.

Reimer’s Witnesses to Text 7, Including Simon’s Witness (By Then Lost or Missing)

Reimer’s edition of the text has more to say on the subject of witnesses for it — accessible and not. It is worth taking his words for it, for what they are worth.

= Heinrich Reimer, Hessisches Urkundenbuch, II. Urkundenbuch zur Geschichte der Herren von Hanau und der ehemaligen Provinz Hanau, 1: 767–1300 (Leipzig: S. Hirzel, 1891), No. 196 (pp. 150–151).

In which “Kaiser Friedrich II nimmt das kloster Selbold mit den aufgeführgen besitzungen in seinen schutz”.

Witnesses:

“Das original, welches 1543 im Gelnhäuser stadtarchiv [sic, in lowercase] hinterlegt wurde, ist verloren gegangen. Dagegen hahen sich mehrere abschriften eines kaiserlichen transsumptes dieser urkunde, von 1363 jan. 21, im Birsteiner archiv erhalten [emphasis added]. Zu grunde gelegt ist eine abschrift des 15. jahrhunderts auf pergament (A.), eine andere von etwa 1370 auf papier (B) ist zwar in den erhaltenen theilen recht gtu [sic, presumably for gut], aber unvollständig; ausserdem ist daselbst noch eine des 15. jahrhunderts auf papier (C); eine des 16. jahrhunderts im Selbolder kopialbuche (D), die vollständigste, ist von Wenck II 153 abgrdruckt worden. Eine fünfte abschrift (E) befindet sich in der abschriftensammlung. Eine sechste abschrifte endlich aus dem 14. jahrhundert (F), welche Simon III 13 [i. e. page 13] zu seinem abdruckt benützte, ist nicht wieder aufgefunden worden [highlights added]. Böhmer–Ficker [Regesta imperii, V, no.] 2170.

That is,

The *Original (that is, the document itself), which had been deposited in the City Archive of Gelnhaus in 1543, is “lost”.

However, multiple “copies” or “transcripts” (Abschriften) of an imperial Transsumpt of that document of “1363 jan. 21” are to be found in the archive at Birstein.

Among those “multiples”, Reimer’s edition employed:

A. 1st, a 15th-century copy on parchment (presumably a document).

B. 2nd, another copy of circa 1370 on paper (presumably a document), damaged and incomplete.

C. 3rd, another 15th-century copy on paper (presumably a document).

D. 4th, a 16th-century copy in the Selbold kopialbuche — “the most complete”, published by Wenck (“II 153”).

E. a 5th copy, preserved in the Abschriftensammlung [presumably likewise at Birstein].

F. A 6th copy, of the “late 14th century”, which Simon used for his edition (Vol. III, [page] 13 [= no. IV]), but “no longer to be found”.

Might Witness “F” be the Selbold Cartulary before its Fragmentation, or a “twin” or close relative? Important if so.

Reimer’s report makes it clear that he had no access directly to the 6th witness, F, which he knew instead through Simon’s edition. We might wonder what, in the interval between Simon’s preparations for his publication of 1865 and Reimer’s publication by 1891, had happened to that copy in the prince’s private collection, or to conditions of access to it. Bruno, Prince of Ysenburg and Büdingen, remained prince from 16 February 1861 to 26 January 1906, so other factors than his position and title may have changed.

Selbold Cartulary Fragment folio “3” verso upper portion. Text 7: Frederick II, May 1236.

The Usefulness of Collation

Reimer’s cited variants to his edition of this text signal some particularities of the texts in D and F, respectively at Birstein in the Selbold Copialbuche and in Prince Bruno’s “private collection”. These variants may be relevant to our quest.

Selbold Cartulary Fragment folio “3” verso upper portion. Text 7: Frederick II, May 1236.

According with time-tested editorial practice, Reimer’s presentation of variants for No. 196 (pp. 150–151) signals a place in the printed text by a numeral-call designating a specific reading (shown here in line 1 of each group or Set) which had been selected for the edition proper. Matching that number in the lower margin, variants are reported, as that ‘standard is held up to the readings found in other witnesses. Here we focus upon the reported variant readings of D and F, which stand sometimes in agreement and sometimes at variance with each other.

Private Collection, Document of 23 Richard II (1399), Face.

Most cases of interest here concern the spellings of place-names. (Readers of this blog may be aware of the value in attending to the differently recorded versions of names for a same place across time, as with A Charter of 1399 from High Ongar in Essex and Fragments of a Castle ‘Capbreu’ from Catalonia.)

Another area of interest concerns the presence or the spelling of the indiction at the end of the dating clause.

From the edited text and the reported variants, we compile all Reimer’s witnesses’ versions of strings of place-names or single names (in his edited text and variant notes 1–3), and variants for the concluding phrase (his text and note 7):

Set 1) Text: Huttengesezze, Widerams

Variants:

Hittengesesze Wiedderams C

Hittengesesse Witterams D

Hittengeseze Witteramis F

Set 2) Text: Gonsrode, Laubersbach, Mittela, Miroldis, Heyleyrs, Geynlnusen, Heyzs

Variants:

. .srode Mittela Laubersbach Myeruloz Heylers Geylnhusen Heycz B

Gunszrode Laubersbach Mittela Miroldes Heylers Geilnhusen Heyzs C

Gunsrodes Lobberbach Mittla Miroldis Heilers Geilnhusen Haytz D & F, “doch gibt F die form Hectzs” [as reported by Simon in contrast to Wencks].

Set 3) Weychirsbach

Variants:

Weichtersbach C.E

Wechtersbach D, Weterbach F.

Set 7) nona indicitione

Variants:

fehlt in A.C.E [that is, absent in these other witnesses]

none indictionis D.F.

The subtle but telling variants seem to show that D and F, at any rate for this text as edited by several scholars, are closely related, but not identical. The date-ranges ascribed to them give a chronological priority to the late-medieval F over the 16th-century D. Is the one a close copy of the other, or of a close relative?

A German translation from Reimer’s edition of the Latin text is offered by Ferdinand Graef, in celebration of “775 Jahre Ronneburg — die Romanik als Geburtsstunde” (1236–2011. Die Urkunde des Staufer Kaisers Friedrich II), noting these first extant references to the places Altwiedermus (as Witteramis) and Hüttengesäβ (as Hittengeseze). Moreover, we learn,”die Originalurkunde liegt im Archiv des Birsteiner Shlosses (Isenburger Archiv) — dort im sogennanten Selbolder Copialbuch“. The terminology names the archive and its location, but appears imprecisely to consider the “original document (Originalurkunde)” as being “within the so-called Selbold Copialbuch” — which takes the form of a codex.

(There exist some manuscripts — in codex form — which contain images, as ‘facsimilies’, of documents, sometimes replete with their tags and seals. Notable cases include the sole witness to the Chronicle of Saint Augustine’s Abbey, Canterbury, by its monk Thomas of Elmham; and chronicles by Matthew Paris, monk at Saint Albans’ Abbey, as examined here. Such cases seem to be unusual among surviving witnesses to their genre, and there appears to be no evidence that the Selbold Cartulary, in one form or other, comprised such an exception.)

Reimer’s edition, variously by his name or by its name, is cited as the source for the text of this document in various locations online, for example when the Historisches Ortslexikon reports the Historische Namesformen for Hüttengesäβ, including the recorded forms

“Huttengesezze; Hittengesesze; Hittengesesse; Hittengeseze (1236) [Kop. 14.-16. Jahrhundert Urkundenbuch Hanau 1, Nr. 196, S. 150-151].”

All those forms appear in Reimer’s standard for the edition and his variant note 1 (as above). Even if (as might be), the Selbold Cartulary Fragment constitutes a previously unrecognized witness to this text, its readings conform with the edition and recorded variants.

Regarding the history of Hüttengesäβ itself, we are given online some further details about the witness cited by Reimer in “the Birstein archive”, although the wording of those details sometimes blur the distinction between “copies’ made in different forms of objects:

- a document (Urkunde) which, while of later date, includes or inserts the text of an earlier document, as a Transsumpt (or “Insert”) proper, and

- a transcription of such a document — with or without an image or rendition of a seal — into codex form (Buch) in a series of pages.

Aerial Photograph of Hüttengesäß, Ronneburg (Hessen), from the South South East.. Photo Dr. Bernd Gross (20 March 2014, 12:08:32). Image via Creative Commons.

Online we read about Hüttengesäβ:

Die älteste erhaltene Erwähnung des Ortes stammt aus dem Mai 1236 und findet sich in einer Urkunde des Kaisers Friedrich II., der die Besitztümer des Klosters Selbold in Schutz nimmt. Die älteste Schreibweise des Ortsnamens ist „Huttengesezze“. Ein Transsumpt dieser Urkunde befindet sich heute im Selbolder Kopialbuch im Fürstlich Isenburgischen Archiv in Birstein.

That Archive resides at Schloss Birstein. While it remains temporarily closed [Spring 2020], the chance to discover the characteristics of its Selbold Kopialbuch must to resort to available descriptions by scholars and editors. That the terminology employed by editors and others for “documents”, “originals”, “transsumpts”, “copies”, and “books” or “copialbucher” shows some overlap, blurring, and/or outright confusion, probably goes with the linguistic territory.

(Don’t get me started on the frequent confusion between “tapestry”, “embroidery”, and other forms of needlework in the descriptions, including by scholars who should know better, of such monuments as the Bayeux so-called Tapestry . . . You could read what I have succinctly to say in the close study of the descriptions of a lost work which may have been related to it: The Bryhtnoth Tapestry or Embroidery, wherein clear attention to the terminology, and the precision or otherwise adopted in its usage, can aid considerably in endeavoring to reconstruct in some measure a lost or missing monument.)

Briefly, before turning to Text 8, we note the locations, actual or presumed, of the Selbold Copialbuch and the Selbold Cartulary Fragments in modern parts of their history.

Schloss Birstein versus Schloss Büdingen

These are, remember, the locations pertaining to the Isenburg and Ysenburg lines of descent and influence (see above).

The entrance to the Archive at Schloss Birstein, home of the Selbold Copialbuch:

Schloss Birnstein, Main Entrance leading to the Archivebau. Photo by Sarkana 2009 via Creative Commons.

Schloss Büdingen, the presumed former home of the Selbold Cartulary Fragment:

Schloss Büdingen seen from the Schlosspark. Photograph by Hadig 2004. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Possible provenance? Further research might reveal where Prince Bruno of Ysenburg and Büdingen kept his collection of manuscripts and archives, and what happened to at least the part of it edited by Simon.

Bruno zu Ysenburg und Büdingen (1837-1906), 3. Fürst zu Ysingen-Büdingen (postcard). Image Public Domain via http://worldroots.com/brigitte/royal/royala-i.htm.

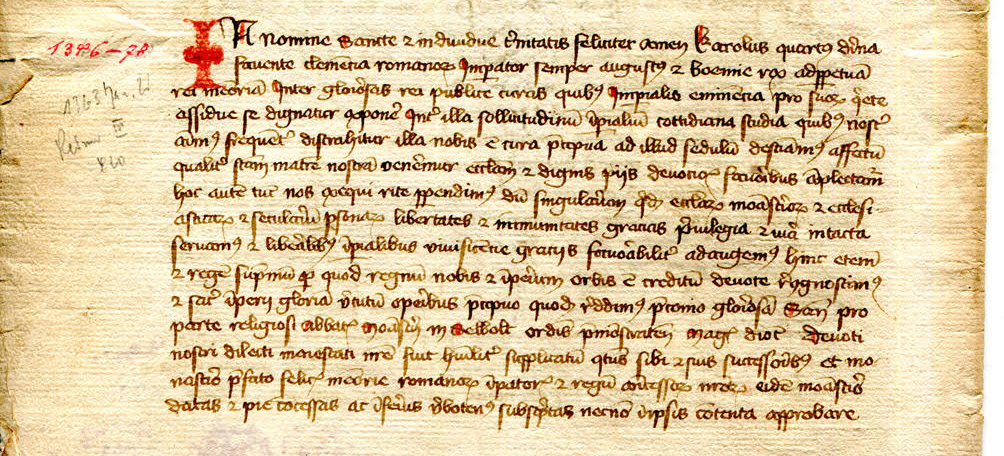

Text 8. Karl IV, [22 January 1363 at Aschaffenburg], Incomplete

Folio “3” v

Selbold Cartulary Fragment folio “3” verso lower portion.

— “1346–76” stated in red ink at the left

— “1363 jan. 22” stated in pencil at the left

The fragment reproduces the first portion of the text, beginning with “In nomine sancte et individue trinitatis . . . consenta approbare [ / ratificare innovare . . . ], and breaking breaking off abruptly in line 33 of this printed edition:

= Heinrich Reimer, Hessisches Urkundenbuch. Zweite Abtheilung. Urkundenbuch zur Geschichte der Herren von Hanau und der ehemaligen Provinz Hanau. Band III: 1350–1375 (Leipzig: S. Hirzei, 1894), No. 420 (pages 466–468).

In which “Kaiser Karl bestätigt dem Kloster Selbold die königlichen unter kaiserlichen gnadenbriefe von 1143, 1236, 1288 und 1293. Aschaffenburg 1363 januar 21.” (page 462).

Reimer described thus the 4 witnesses consulted for his edition of the document, along with another witness now lost (p. 468):

In vier wiedergaben erhalten:

A ist eine etwa gleichzeitige abschrift auf papier, die in der obenen hälfte sehr beschädigt ist und namentlich in den eingerückten königsurkunden grosse lücken zeigt. Diese sind im vorigen jahrh. ergänzt worden.

B pergamentabschrift des 15. jahrh., nur in der ersten hälfte erhalten.

C abschrift des 16 jahrh. im kopialbuche des klosters Selbold (hiernach abschrift in Wencks nachlasse zu Darmstadt).

D abschrift des 18 jahrh. nach einer 1434 beglaubigten abschrift einer 1414 beglaubigten abschrift.

Birstein. — Das orig. war nach einer notiz des Selbolder kopialbuchs 1543 noch vorhanden; es gehörte zu den Isenburg und Gelnhausen im rathsarchive zu Gelnhausen gemeinschaftlich hinterlegten urkunden. [Birstein] B R 3910 nach abschrift.

These 4 witnesses, each one called an Abschrift (“copy” or “transcript”), evidently comprise both documents and transcriptions in book-form. That is:

- a “more-or-less contemporary A on paper”, presumably a document, because said to be in “very damaged” condition in its upper half

- a 15th-century parchment copy B, presumably also a document, surviving “only in its first [or upper] half”

- a 16th-century copy C in the Kopialbuch (“Copy-Book”) of the monastery of Selbold, said parenthetically to be hiernach (“after this”) abschrift “in Wenck’s estate at Darmstadt” — presumably that of the historian and editor Helfrich Bernhard Wenck (1739–1803)

- an 18th-century copy [where?], made from an “authenticated” copy of 1434 from an “authenticated” copy of 1414.

As for the “original” document itself, it was extant in 1543 at Gelnhausen (according to a note in the Selbold Kopialbuch), but apparently no longer.

Reimer’s account of C seems not entirely clear. Had the 16th-century Selbold Kopialbuch or perhaps a 16th-century copy of it migrated to Darmstadt as part of Wenck’s estate? Or was the Abschrift afterward (hiernach) at Darmstadt (where Wenck had resided) a copy of the Kopialbuch — or this part of it — made by or for Wenck? If so, it would have been made in the latter 18th or early 19th century, say in connection with the work on his publication of Hessisches Landesgeschichte in 3 volumes (1783–1803). Further investigation of Reimer’s editions of Selbold texts not represented on the Selbold Cartulary Fragments shows some of the answer. See below.

The Selbold Cartulary Fragments on paper showcased here fit within such patterns of transmission indicated or implied by Reimer’s account. These leaves deserve to be counted among the surviving witnesses to the Selbold documents and cartularies, many of which changed hands and locations — sometimes recorded — over the course of time.

The Selbold Kopialbuch(e)

It might be wondered to what extent “our” showcased manuscript, before its dismemberment, resembled the source which some editors called the Selbolder Cop.-Buche, the kopialbuche des klosters Selbold, the Selbold kopialbuch, and the like, as highlighted in red in the quotations above and below. Occasionally the cited witnesses include other Kopialbucher relating to Selbold, but not, evidently, the one(s) for the Kloster or Stift. We highlight those, insofar as they can be discerned, in purple.

Editions of other parts of the Selbold Kopialbuche demonstrate more of its holdings, including texts of documents in Latin and in the vernacular. (They might also indicate, mutatis mutandis, more of the range of texts possibly in the manuscript from which came the Selbold Cartulary Fragments.) Texts cited with it specifically as the, or a, witness appear, for example, here:

1. Arthur Franz Wilhelm Wyss, Hessisches Urkundenbuch, I. Urkunden der Deutschordens–Ballei Hessen, 1: Von 1207 bis 1299 (Leipsig: S. Hirzel, 1878):

-

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France. Département des Manuscrits. Français 12201 (circa 1420-1430), fol. 1r, detail. Presentation illustration in which Hayton of Corycus remits his report on the Mongols to Pope Clement V (in 1307). Image via gallica.bnf.fr.

No. 97 (page 98). Pope Clement V at Vienna on 1310 November 3

- No. 314 (pages 292–293). Mechtild, widow of Eberhard von Breuberg on 1327 June 25

- No. 594 (p. 585). Rudolf von Hain et al. on 1342 March 30

- No. 652 (pp. 538–539). Kaiser Ludwig II at Frankfurt on 1344 August 23

For one text (no. 594), Wyss used both the Selbold Kopialbuche and another witness also from Selbold, but from and/or for its “parish”: the “kopialbuche über die pfarreien Selbold, Mittlau u. a. Birstein” (p. 585).

Heinrich Reimer used the Selbold Kopialbuch frequently in his 3-volume edition of documents from Hessen, with occasional appearances by the kopialbuche über die pfarreien Selbold and the kopialbuche des Selboldische gerichtes, as well as by a copy “ex libr. cop.” (or “ex. cop. ant.“) — which had been owned by, and perhaps made by or for, Wencks. There is also a Rotes Buch (“Red Book”) of some kind.

Let us consider Reimer’s volumes in reverse chronological order of their documents.

2. Heinrich Reimer, Hessisches Urkundenbuch, II. Urkundenbuch zur Geschichte der Herren von Hanau und der ehemaligen Provinz Hanau, 2: 1301–1349, (Leipzig, 1892)

- No. 97 (p. 98). Pope Clement V at Vienna on 1319 November 3.

“Orig.-perg. . . . Die lücke am schlusse is aus dem Selbolder kopialbuche ergänzt. Birstein” - No. 314 (pp. 292–293). Mechtild, widow of Eberhard von Breuberg on 1327 June 25.

“Zwei abschriften, eine in kopialbuch des klosters Selbold und eine in kopialbuche des gerichts Selbold. Birstein“. - No. 460 (pp. 430–431). Pope Benedict XII at Avignon on 1336 April 12.

- No. 461 (p. 431). Ditto.

- No 503 (pp. 481–482). Konrad Blumichen, “burgman zu Gelnhausen” on 1338 July 10.

- No. 505 (pp. 483–484). Rudolf von Rückingen on 1338 July 13.

- No. 590 (pp. 532–533). Abbot Johannes von Prémontré at Prémontré in 1341.

- No. 594 (p. 585). Rudolf von Hain, his wife, and his son on 1342 March 30.

- No. 621 (pp. 612–613). Rudolf the Elder von Rückingen aand his wife Metze on 1343 April 25.

“Kopialbuch der Selboldischen pfarrein, saec. XVI., papier. Birstein. Eine abschrift «ex libr. cop.» in Wencks nachlasse zu Darmstadt”. - No. 635 (pp. 626–627). Abbot Johannes von Prémontré at Prémontré in 1343.

- No. 652 (pp. 638–639). Kaiser Ludwig at Frankfurt on 1344 August 23.

“Abschrift «ex libr. ant.» in Wencks nachlasse zu Darmstadt. Modernisierte abschrift in Selbolder kopialbuche (nr. 31) und im kopialbuche der Selbolder pfarreien (34), Birstein. BR 2404, seitdem gedr.: Simon III 139″. - No. 749 (pp. 729–732). Graf Rudolf von Wertheim, his wife Elysabeth, and their son Eberhart on 1348 May 2.

“Rothes Buch (A.) und Selbolder kopialbuch (B), beide in Birstein”. - No. 751 (p. 734). Graf Rudolf and Eberhard von Wertheim on 1348 June 13.

“Rothes Buch zu Birstein (A.) f. 148r, auch im kopialbuch des Selbolder gerichtes daselbst”. - No. 802 (pp. 795–797) Abbot Helfrich and the Kloster Schlüchtern on 1349 September 29.

“Kopialbuch der Selboldischen pfarreien (Mscr.-samml. nr. 34) (A.) und eine abschrift vom ende des 18. jahrhunderts (B.), beide in Birstein.

In this publication, Reimer occasionally mentioned a pressmark for the “Selbold Kopialbuche (i, e., 31)” as well as for at least one other Kopialbuch pertaining to Selbold: the “Kopialbuch der Selboldischen pfarreien (Mscr.-samml. nr. 34)“. Unnumbered in his citation of witnesses is the kopialbuche des gerichts Selbold also at Birstein. Only rarely, and for none of these witnesses, did Reimer specify a folio number, as he did with the “Rothes Buch zu Birstein (A.) f. 148r” (No. 751) — whose name of “Red Book” presumably derived from the color of its binding, as often in medieval parlance.

Such editorial practices impede the chances of discerning with much precision the probable order of texts in any cartulary which may have underpinned the early-modern Selbold Copialbuch at Birstein, or any other copies of that earlier cartulary produced beforehand, including the Selbold Cartulary Fragments with unnumbered folios.

3. Heinrich Reimer, Hessisches Urkundenbuch, II. Urkundenbuch zur Geschichte der Herren von Hanau und der ehemaligen Provinz Hanau, 1: 767–1300 (Leipzig: S. Hirzel, 1891) frequently cited as witness the Abschrift im Selbolder kopialbuche zu Birstein. He did so for all these texts — often as the only witness, with a few notices (indicated here) of some 16th-century elements in it and/or other companions.

-

Archives of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, Rhodes, and Malta: “Piae Postulatio Voluntatis”. Bull issued by Pope Paschal II in 1113 in favour of the Order of St. John Hospitalier. Image Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

No. 70 (pp. 46–47). Pope Paschal II at Benevento on 1108 October 16.

- No. 77 (pp. 50–52). Pope Innocent II at the Lateran on 1139 April 25.

“Abschrift des 16. Jahrhunderts im Selbolder kopialbuche, Birstein“. - No. 90 (pp. 62–64). Archbishop Heinrich I of Mainz on 1151 May 25 [Text 1 here].

- No. 91 (pp. 64–65). Ditto [Text 2 here].

- No. 97 (pp. 70–72). Pope Hadrian IV at Sutri on 1158 June 12.

- No. 106 (pp. 83–84). “Abgrenzung der besitzunden der klöster Selbold und Meerholz” on 1173 September 14.

“Abschrift aus der mitte des 14. jahrhunderts auf einem perg.-blatt in Birstein und im Selbolder kopialbuche daselbt”. - No. 131 (pp. 104–105). Frederick II at Fulda on 1217 August 15 [Texts 4–5 here].

- No. 134 (p. 107). Pope Honorius III at the Lateran on 1219 March 14.

Also: “Kopp, De insigni differentia 366 (erster druck) und (nach Würdtwein: Unbefang)”. - No. 156 (p. 122). Pope Honorius III at the Lateran on 1223 March 30.

- No. 182 (pages 140–141). Papal judgement for a Selbold dispute over the hospital and chapel at Gelnhaus on 1234 August 20.

Also: “Das original erheilt 1543 der rath von Gelnhausen zur aufbewahrung”. - No. 186 (pages 143–144). Kloster Selbold settles a dispute between 2 brothers over an estate at Gondsroth “um 1234”.

- No. 196 (pp. 150–151). Frederick II at Würzburg in 1236 May [Text 7 here], with notes and variants (See above).

- No. 197 (pp. 151–152. Variant of the same: “Gleicher schutzbrief des kaisers ohne aufführung der besitzungen”.

- No. 198 (pp. 152–153). Pope Gregory IX at the Lateran on 1237 March 19.

- No. 386 (pp. 283–284). The town of Gelnhausen recognizes the payment of tithe by Ulrich von Krutorf to Kloster Selbold in 1259–1262.

Also: The original had been deposited, after the disbanding of the Kloster in 1543, at the Gelnhausen Stadtarchive etc. - No. 403 (pp. 288–289). Pope Clement IV at Perugia on 1265 June 17.

- No. 404 (p. 299). Pope Clement IV at Perugia on 1265 June 22.

- No. 445 (pp. 330–331). King Richard at Frankfurt 1269 May 23 [= Richard, Earl of Cornwall, King of the Romans (1209-1272)].

- No. 541 (pp. 299–390). Archishop Werner of Mainz at Aschaffenburg on 1277 June 22.

- No. 556 (p. 398). Ludwig von Isenburg on 1278 April 5.

-

Lead Papal Bulla issued between 1227 and 1241 under Pope Gregory IX, Face and Dorse. Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) FindID 407324 (Hampshire). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

No. 563 (pp. 402–403). Ludwig von Isenburg at Büdingen on 1278 August 7.

Also: “Kopp gibt in seiner handschriftlichen Chronik . . . diese urkunde . . . d.h. dem veloren [*]copialbuche des 14. jahrhunderts“ - No. 589 (pp. 421–421). Archishop Werner of Mainz at Aschaffenburg on 1280 March 21.

Also: “Regestiert: Simon III 35”, etc. - No. 632 (pp. 452–453). Berthold Gross, bürger of Gelnhausen, and his wife Godestu on 1285 August 19

— with “Zwei abschriften im Selbolder kopialbuche zu Birstein“ - No. 668 (pp. 478–479). Walter and Berthold von Liesberg on 1288 September 20.

- No. 731 (p. 532). Abbot Wilhelm of Premontré Abbey in 1292.

- No. 759 (p. 553–554). King Adolf at Gelnhausen on 1296 June 14. [Text 6 here].

In one case (No. 632), Reimer noted the presence of 2 copies in the Selbold kopialbuche — similar, it may be, to the double (or varied) copies of some texts in the fragment which we consider here (Texts 1–2 and 4–5).

In another case (No. 186), Reimer made his edition from the original document at Birstein, but noted that the text had been edited by Simon — “badly” and misdated — from the, or a, copialbuch: “Gedr.: Simon III 72 (nach copialbuch [rightly here in red?], schlecht und mit der datierung: um 1300)”.

In another case (No. 563), where the edited text from the Selbold kopialbuch has the reading of MCCLXXVIII in vigilia Ciriaci (= 7 August for the day before the feast-day of Saint Cyriacus) in the year 1278, Reimer noted [Johann Adam] Kopp’s transcription with the date instead of “1280 in vigilia Circumcisionis” (= 31 December), from the lost 14th-century Selbold *Liber or *copialbuche, in his handwritten Chronik . . . der Grafen von Ysenberg [in the “Büdinger Archiv”, presumably the Büdinger Stadtarchiv], with 2 copies of that Chronik kept in the Hanauische Geschichtsverein.

This is how Reimer densely expressed it:

Kopp gibt in seiner handschriftlichen Chronik . . . der Grafen von Ysenberg (von welcher der Hanauische geschichtsverein zwei abscriften besitzt) diese urkunde «ex [*]libro privilegiorum et libertatum ecclesiae Selboldensis» d. h. dem veloren [*]copialbuche des 14. jahrhunderts, mit 1280 in vigilia Circumcisionis [whereas the edited text from the Selbold kopialbuch has the variant MCCLXXVIII in vigilia Ciriaci].

(I take care to include the full quotation, along with my construction of its meaning, as the compacted phraseology calls for close reading, or “unpacking”.) Reimer also noted that the text of No. 563 had been “printed” already: “Gedr.: Kopp De insigni differentia 446”. That is:

= Johann Adam Kopp, Tractatus Iuris Publici De insigni differentia inter S. R. J. Comites et Nobiles immediatos . . . (Strassburg, 2nd ed., 1725), Supplementum, no. 44 (p. 446), from the [*]Libro Msto. Privilegior. Eccles. Selbold. (p. 146). That is, from the “Mixed or Miscellaneous (misto, a variant or corruption of mixto, from the verb misceo) Book of the Privileges of the Church of Selbold“.

In the same publication, Kopp cited (p. 128) a document of 1217 issued by Gerlacus de Budingen [apparently the same person named in Text 4], from that selfsame book, which he named with precisely the same title. Shall we guess or presume that the book itself carried that title? Sounds plausible.

Kopp (1698–1748), a jurist, dedicated his publication to Wolfgang Ernst I von Isenburg-Büdingen-Birstein (1686–1754), Count of Isenburg-Birstein from 1711 to 1744. Might the acquaintance with, and access to, that [*]Liber have related to its physical location within that sphere of influence and patronage? Such a pattern might have resembled the access in a later generation which Gustav Simon obtained for the late-medieval witness owned by Prince Bruno of Ysenburg and Büdingen.

In fact, the lines of descent of titles of Counts and Princes (Grafen und Fursten von Ysenburg and Büdingen) lead directly from Count Wolfgang Ernest I to the series of Counts and then Princes of Isenburg-Büdingen-Büdingen. The last of the Counts is Ernst Casimir (1758–1801), father of the first Prince of Ysenburg-Büdingen-Büdingen, Ernest Casimir (1801–1848), and grandfather of the third Prince, Bruno. (See Isenburg-Büdingen and Isenburg-Büdingen.) With those patterns of lineal transmission would also have come properties and possessions. Books included? Especially ones that adorn and document those forms of possession, we might think.

From the reports available to Reimer of such a Liber for the Church of Selbold, having detectable textual variants from the Selbold Copialbuch which remained in view for his edition, he found it necessary to recognize that such a book had existed, even if no longer to hand. In his gloss on Kopp’s notice, Reimer equated that Liber unquestionably with “the lost 14th-century Copialbuche“:

«ex libro privilegiorum et libertatum ecclesiae Selboldensis» d.[as] h.[eißt] dem veloren copialbuche des 14. jahrhunderts (p. 403).

Could be? Might it have been hiding in plain sight, if one knew where to look, or been moved into hiding?

Here I refer to that manuscript, whether lost or lost sight of, as the Selbold *Liber Priviligiorum or *Kopialbuch. Rightly or not, Reimer regarded it as the exemplar from which the extant Selbold Kopialbuch at Birstein was copied.

Sight unseen, we must depend upon published descriptions or citations of that extant book for reports of its structure, contents, appearance, and date-range of production. Some information emerges, as we can see, in scattered locations across notes and references in the various editions which derive their texts from the Selbold Kopialbuch among others. Among those whose works have been able to consult in a time of widespread library-closures or lock-downs (Spring 2020), rarely (if at all) did an editor give a clear and consistent description of the book among his consulted witnesses.

The 14th-Century (*)Liber Priviligiorum / Kopialbuche on Paper

And a 16th-Century Copy on Paper (the Selbold Kopialbuche) in Birstein

(Among Others)

In the Vorwort to his edition, when turning to “Kloster Selbold” (pp. xxii–xxiii), Reimer described the sources. The descriptions are both revealing and tantalizing. Thus (p. xxiii), with added highlights and colors:

In 14. Jahrhundert wurde im Kloster ein [*]Kopialbuch auf Papier angelegt, das den Titel fürhte: Liber privilegiorum et libertatum ecclesie Selboldensis. Noch im vorigen Jahrhundert benutzte es [Johann Adam] Kopp in seiner handschriftlichen Geschichte der Herren und Grafen von Ysenburg [note 1: “Original im Büdinger Archiv, zwei Abschriften in Besize des Hanauer Greshichtsvereins”], bis jezt ist es aber nicht vieder aufgefunden vorden. Glüchlicherweise ist es ganz oder zum grösten Theile abschriftlich in ein Kopialbuch des 16. Jahrhunderts aufgenomen worden. Dieses (Manuscriptensammlung 31 zu Birstein) hat 175 beschriebene Papierblätter und ist in eine Pergament-Urkunde von 1540 eingebunden.