Simurgh and Zal from a Persian “Shahnameh”

May 7, 2020 in Manuscript Studies, Uncategorized

Simurgh and Zaal

from a Persian Shahnameh

[Posted on 7 May 2020]

Continuing to examine manuscripts or manuscript fragments and related materials in our blog, we turn to an illustrated paper leaf, now in a private collection, from a Persian Shahnameh or ŠĀH-NĀMA (“Book of Kings”).

The Contents List for our blog shows the range of our explorations. Our Galleries of Scripts on Parade include specimens of script in Persian as well as other languages, Western and non-Western.

The Paper Leaf

The leaf was purchased in the Portabello Road in London circa 1985. The paper is typical of Persian paper from at least the fifteenth through the nineteenth centuries CE. One side has text, and the other has both text and inset illustration. The ensemble probably dates from the 19th century, with acquired damage of various kinds, including unevenly trimmed edges.

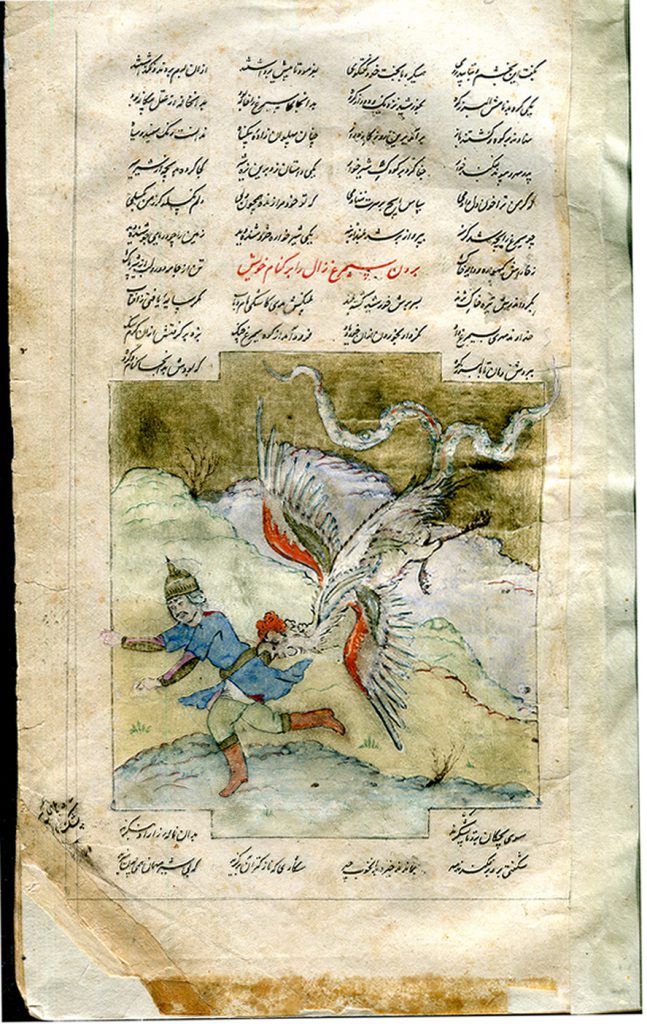

Private Collection, Leaf from a Persian Shanameh. Simurgh and Zal.

The Shahnameh

This long epic poem, which the Persian poet Abul-Qâsem Ferdowsi Tusi or Ferdowsi (circa 329 – 411 AH / 940 – 1010 CE) began to compose circa 977 and completed on 8 March 1010 CE, forms a major work of world literature. It recounts in more than 50,000 couplets the history of the kings and heroes of Persia from mythical times to the overthrow of the Sassanids by the Arabs in the middle of the 7th century.

Several episodes describe encounters between the benevolent mythical, phoenix-like creature Simurgh and Zāl or Zaal, the legendary prince who, born with white hair, grew into a heroic warrior king. This illustration shows the gigantic creature with the man in adulthood.

This creature had rescued him as an infant when his parents, in fear of his albino appearance, had abandoned him on the mountain Alborz, where Simurgh dwelled. She raised him as her own and taught him wisdom. After Zāl’s return to his kingdom and the world of mankind, he summoned Simurgh’s expertise for aid when his wife Rudaba was undergoing prolonged labor in childbirth — leading to the birth of the great hero Rostam. That aid took the form of instructing Zāl how to perform a caesarean section.

Illustrations in Manuscripts

The long tradition of illustrations for the Shahnameh or Šāh-nāma is richly varied, in books and other visual arts, and in Persian and other spheres. We learn that the documented history of its illustration in manuscripts begins circa 1300 “in the Il-khanid period (1256–1353), coinciding with the start of the canonical history of Persian painting”. There developed varied approaches to the choices of episodes illustrated, the positioning of the illustrations upon the leaves and at regular or irregular intervals through the course of the volumes, the manner of depicting a given episode, and artistic license. In sum, “there was no prescribed manner for depicting the same episode”, and “there was no fixed set of Šāh-nāma illustrations”. From these rich origins developed the unfolding traditions of manuscript illustration for this text in later dynasties and regions, Persian and other.

Among the very most magnificent representatives of the tradition is the now-dismembered and dispersed Shahnamen of Shah Tahmasp, made at Tabriz by many artists circa 1525–1530 CE and completed for Shah Tahmasp (1514–1576). That manuscript, preserved in multiple collections, probably originally comprised two volumes with some 280 large folios and 190 illustrations. Some collections exhibit online a range of its illustrations, as with the 10 folios in the Houghton Shahnameh and some of the 78 illustrated pages at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

That the manuscript tradition could continue to flourish into the 19th century (and beyond) is demonstrated by the copy at the Morgan Library & Museum, as MS H. 9, made probably in Shīrāz, Iran, between 1852 and 1856.

Perhaps needless to say, at various times in the widespread transmission of the text of the Shahnameh and its illustrated versions, non-royal patronage and commercial production also flourished, up to and beyond the history of printing. Given the history of collecting, it seems inevitable that specimens of any standard of quality or otherwise might find their way to fragmented and widely dispersed states of existence or survival. As such, the leaf presented here stands in a very large but vastly separated crowd.

Simurgh and Zāl

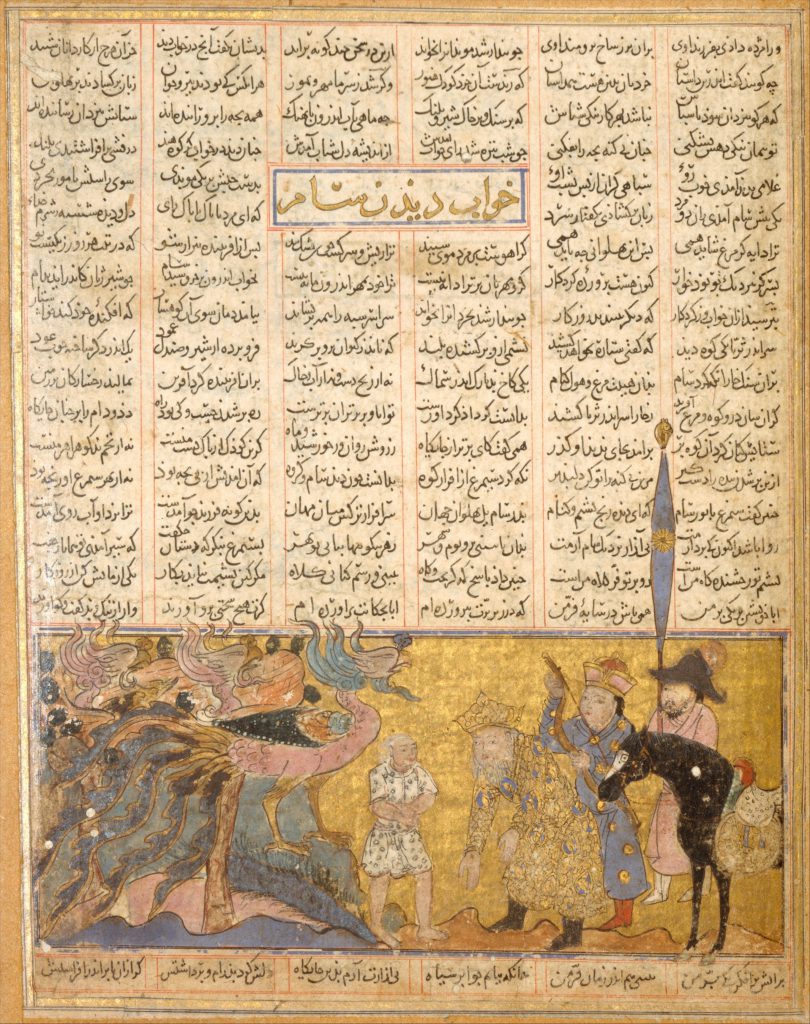

The fabulous story of Simurgh and Zāl offers ample scope for vivid depictions. Many expert examples reside in major collections, as with this case at the Metropolitan Museum in New York of circa 1300–1330 CE, aattributed to Northwestern Iran or Baghdad (MMA Rogers Fund 1969, 69.74.1).

New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Folio from a Shahnama, circa 1300–30 CE. “Zal is Restored to his Father Sam by the Simurgh”. Image Public Domain.

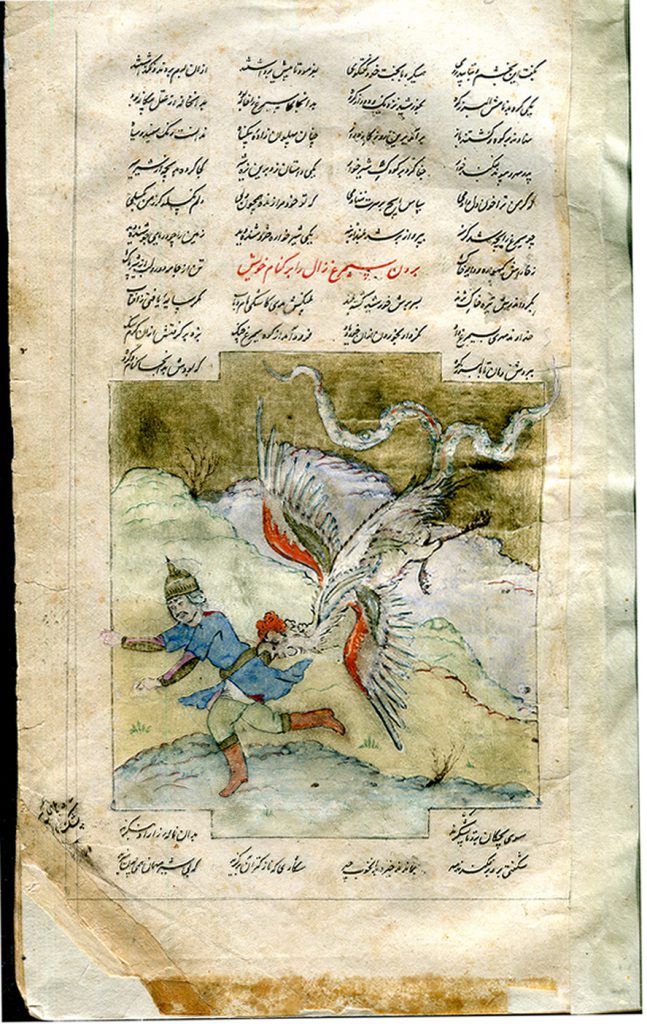

Or this elaborate version from the famous Tahmasp (or Ṭahmāsp) Shahnamah (see above) at the Freer Gallery in Washington D. C., in which a passing caravan sights Zal with Simurgh as she brings food for him and her nesting chicks.

Washington, D. C., Freer Gallery of Art, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, LTS1995.2.46: Tahmasp Shahnamah, folio 62v. Iran, Tabriz, circa 1525 CE. “Zal is Sighted by a Caravan as Simurgh Feeds Her Chicks”. Image Public Domain.

The Illustration on Its Page

On the page of “our” leaf, the illustration stands within the text. The fully painted illustration contrasts with the open background of the script, written in black ink with rubrication in red pigment and set out in 4 columns, with 2 to a couplet and 12 lines of text altogether. The heading in red occupies the space of 2 couplets at the center of line 7. Above the illustration stand 10 lines of text, in which the last line spreads to either side of the stepped riser of the illustrated frame, yielding only the 2 outer columns. Below it stand 2 more lines, of which the first similarly spreads around the stepped descender of the frame.

Both the lines of text and the illustration are partly enclosed by an open-topped framework of ink outlines, which form single (or retraced) vertical bounding lines at both sides and a horizontal line at the bottom. Inset within that frame, the painted illustration stands within its own outlined stepped frame which has block-like risers at top and bottom.

Private Collection, Leaf from a Persian Shanameh. Simurgh and Zal.

Zāl’s name figures in the rubric, and his identifying white hair appears to emerge, like an ear-flap, below his helmet. Simurgh assumes a recognizable but perhaps non-standard form, with huge size, spread wings, long tail dividing into streamer-like tips, and red rooster-like crest.

In the illustration, the pair of figures, man and avian, appear against a painted landscape. Descending from the sky, the creature swoops down from the right to nip or clamp the waistband or sash of the fleeing warrior king, whose outstretched right hand reaches beyond the frame partway into its interspace. With helmet and mustache, the man wears boots, trousers, and a knee-length tunic which partly exposes his white undergarment.

Private Collection, Leaf from a Persian Shanameh. Simurgh and Zal.

Mostly, the recounted relationship between the creature and her adopted Zāl appears benign, but here she grabs him — with both of them poised in mid-flight.

Private Collection, Leaf from a Persian Shanameh. Simurgh and Zal.

*****

Detached from its former manuscript, for now this illustrated leaf must stand for the original whole. Do you know of other leaves from this book and by the same scribe and artist?

Please leave your comments here or Contact Us. Watch this space and the Contents List for more discoveries in our blog.

*****